How Leadership Influences Open Government Data (OGD)-Driven Innovation: The Mediating Role of Organizational Commitment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

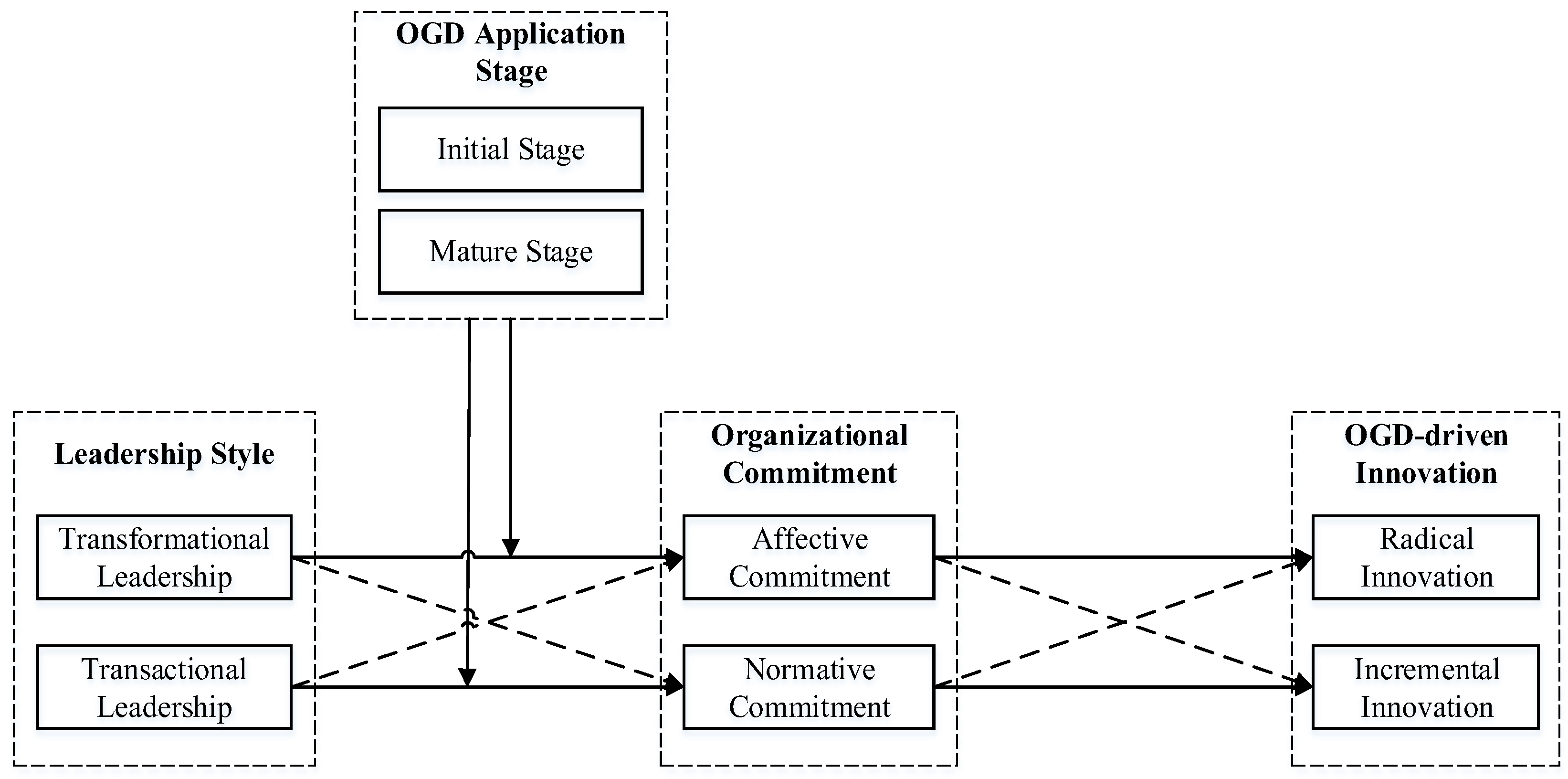

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. OGD-Driven Innovation

2.2. Leadership and OGD-Driven Innovation

2.2.1. Transformational Leadership and OGD-Driven Innovation

2.2.2. Transactional Leadership and OGD-Driven Innovation

2.3. Organizational Commitment as a Mediator

2.3.1. The Mechanism of Affective Commitment

2.3.2. The Mechanism of Normative Commitment

2.4. OGD Application Stage as a Moderator

3. Data and Measures

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussions and Implication

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Measure | Item |

|---|---|

| Transformational and transactional leadership (Waldman, Ramirez, House and Puranam [36] and Avolio, Bass and Jung [51]) | TFL1: He/she articulates a compelling vision of the future. |

| TFL2: He/she has my trust and respect. | |

| TFL3: He/she communicates high performance expectations to me. | |

| TFL4: He/she seeks differing perspectives when solving problems. | |

| TFL5: He/she gets me to look at problems from many different angles. | |

| TFL6: He/she spends time teaching and coaching. | |

| TFL7: He/she considers me as having different needs, abilities, and aspirations from others. | |

| TAL1: He/she provides me with assistance in exchange for my efforts. | |

| TAL2: He/she makes clear what one can expect to receive when performance goals are achieved. | |

| TAL3: He/she reinforces the link between goals and rewards. | |

| TAL4: He/she expresses satisfaction when I meet expectations. | |

| TAL5: He/she takes action if mistakes are made. | |

| TAL6: He/she focuses attention on irregularities, exceptions, or deviations from what is expected. | |

| TAL7: He/she shows a firm believer in “If not broke, don’t fix it.” | |

| Affective and normative commitment (Meyer, Allen and Smith [53]) | AC1: I would be pleased to spend the rest of my career with this firm. |

| AC2: I really feel as if this firm’s problems are my own. | |

| AC3: I do not feel a strong sense of “belonging” to my firm. (R) | |

| AC4: I do not feel “emotionally attached” to this firm. (R) | |

| AC5: I do not feel like “part of the family” at my firm. (R) | |

| AC6: This firm has a great deal of personal meaning for me. | |

| NC1: I do not feel any obligation to remain with my current employer. (R) | |

| NC2: Even if it were to my advantage, I do not feel it would be right to leave my firm now. | |

| NC3: I would feel guilty if I left my firm now. | |

| NC4: This firm deserves my loyalty. | |

| NC5: I would not leave my organization right now because I have a sense of obligation to the people in it. | |

| NC6: I owe a great deal to my firm. | |

| OGD-driven radical innovation and incremental innovation (Chandy and Tellis [17] and Jansen, Van Den Bosch and Volberda [54]) | OGD_ RI1: Introduces products that are radically different from existing product through OGD. |

| OGD_ RI2: New products and services are generated through OGD. | |

| OGD_ RI3: Commercialize products and services that are completely new through OGD. | |

| OGD_ RI4: Search and approach new clients in new markets through OGD. | |

| OGD_ II1: Refine the provision of existing products and services through OGD. | |

| OGD_ II2: Minor improvements to existing products and services through OGD. | |

| OGD_ II3: Introduce improved but existing products and services for local markets through OGD. | |

| OGD_ II4: Increase economies of scales in existing markets through OGD. |

References

- Jetzek, T.; Avital, M.; Bjorn-Andersen, N. Data-driven innovation through open government data. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2014, 9, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leviäkangas, P.; Molarius, R. Open government data policy and value added-Evidence on transport safety agency case. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, G.; Roseira, C. Open government data and the private sector: An empirical view on business models and value creation. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 101248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Frankwick, G.L.; Ramirez, E. Effects of big data analytics and traditional marketing analytics on new product success: A knowledge fusion perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1562–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascó-Hernández, M.; Martin, E.G.; Reggi, L.; Pyo, S.; Luna-Reyes, L.F. Promoting the use of open government data: Cases of training and engagement. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Charalabidis, Y.; Zuiderwijk, A. Benefits, adoption barriers and myths of open data and open government. Inf. Syst. Manage. 2012, 29, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barry, E.; Bannister, F. Barriers to open data release: A view from the top. Inf. Polity 2014, 19, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.-C.; Chen, Y.-C. Enhancing open government information performance: A study of institutional capacity and organizational arrangement in China. Chin. J. Commun. 2015, 8, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijer, E.; Meijer, A. Open government data as an innovation process: Lessons from a living lab experiment. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2019, 43, 613–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jung, D.I. Transformational and transactional leadership and their effects on creativity in groups. Creativ. Res. J. 2001, 13, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Álvarez-Otero, S.; Sulaiman, M.A.B.A.; Sial, M.S.; Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; Omhand, K. Achieving organizational social sustainability through electronic performance appraisal systems: The moderating influence of transformational leadership. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership: Good, better, best. Organ. Dyn. 1985, 13, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.; Junni, P. CEO transformational and transactional leadership and organizational innovation: The moderating role of environmental dynamism. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 1542–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, I.G.; Jansen, J.J.P.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.J.; Volberda, H.W. Management innovation and leadership: The moderating role of organizational size. J. Manage. Stud. 2012, 49, 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Bai, X.; Li, J.J. The influence of leadership on product and process innovations in China: The contingent role of knowledge acquisition capability. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 50, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Badir, Y.F.; Saeed, B.B.; Hafeez, S. Transformational and transactional leadership and employee’s entrepreneurial behavior in knowledge–intensive industries. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.S. Notes on the concept of commitment. Am. J. Sociol. 1960, 66, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arshad, M.A.; Shabbir, M.S.; Mahmood, A.; Sulaiman, M.A.B.A.; Khan, S. Holistic human resource development model in health sector: A phenomenological approach. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 20, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Hirt, E.R.; Karpen, S.C. Lessons from a faraway land: The effect of spatial distance on creative cognition. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, J.; Friedman, R.S.; Liberman, N. Temporal construal effects on abstract and concrete thinking: Consequences for insight and creative cognition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Zeleti, F.; Ojo, A.; Curry, E. Exploring the economic value of open government data. Gov. Inf. Q. 2016, 33, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandy, R.K.; Tellis, G.J. Organizing for radical product innovation: The overlooked role of willingness to cannibalize. J. Mark. Res. 1998, 35, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, J.E. Business model innovation and business concept innovation as the context of incremental innovation and radical innovation. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, R.D.; Dutton, J.E. The adoption of radical and incremental innovations: An empirical analysis. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 1422–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susha, I.; Grönlund, Å.; Janssen, M. Driving factors of service innovation using open government data: An exploratory study of entrepreneurs in two countries. Inf. Polity 2015, 20, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organ. Dyn. 1990, 18, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- House, R.J.; Spangler, W.D.; Woycke, J. Personality and charisma in the U.S. presidency: A psychological theory of leader effectiveness. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 364–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.L.; Avolio, B.J. The charismatic relationship: A dramaturgical perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 32–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvir, T.; Eden, D.; Avolio, B.J.; Shamir, B. Impact of transformational leadership on follower development and performance: A field experiment. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, K.; Lahti, K. Organizational vision and system influences on employee inspiration and organizational performance. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2011, 20, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, J.M.; Avolio, B.J. Transformational leadership, transactional leadership, locus of control, and support for innovation: Key predictors of consolidated-business-unit performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampa, R.; Agogué, M. Developing radical innovation capabilities: Exploring the effects of training employees for creativity and innovation. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2021, 30, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hater, J.J.; Bass, B.M. Superiors’ evaluations and subordinates’ perceptions of transformational and transactional leadership. J. Appl. Psychol. 1988, 73, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.B.; Van Dun, D.H.; Wilderom, C.P. Innovative work behavior in Singapore evoked by transformational leaders through innovation support and readiness. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2021, 30, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosik, J.J.; Avolio, B.J.; Kahai, S.S. Effects of leadership style and anonymity on group potency and effectiveness in a group decision support system environment. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, M.; Stroebe, W. Productivity loss in idea-generating groups: Tracking down the blocking effect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Hill, K.G.; Hennessey, B.A.; Tighe, E.M. The work preference inventory: Assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 950–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R.J. Path-goal theory of leadership: Lessons, legacy, and a reformulated theory. Leadersh. Q. 1996, 7, 323–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M. How to kill creativity. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Waldman, D.A.; Ramirez, G.G.; House, R.J.; Puranam, P. Does leadership matter? CEO leadership attributes and profitability under conditions of perceived environmental uncertainty. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, Y. Commitment in organizations: A normative view. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steers, R.M. Antecedents and outcomes of organizational commitment. Adm. Sci. Q. 1977, 22, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Shin, M.; Billing, T.K.; Bhagat, R.S. Transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and affective organizational commitment: A closer look at their relationships in two distinct national contexts. Asian. Bus. Manag. 2019, 18, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.C.; Mak, W. Transformational leadership, pride in being a follower of the leader and organizational commitment. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 2014, 35, 674–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.A.; Meyer, J.P.; Wang, X.-H. Leadership, commitment, and culture: A meta-analysis. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2013, 20, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.P.; Xue, W.; Li, L.; Wang, A.M.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Q.L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Li, X.J. Leadership style and innovation atmosphere in enterprises: An empirical study. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2018, 135, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y.; McCrea, S.M.; Sherman, S.J. The effect of level of construal on the temporal distance of activity enactment. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liberman, N.; Sagristano, M.D.; Trope, Y. The effect of temporal distance on level of mental construal. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 38, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Parfyonova, N.M. Normative commitment in the workplace: A theoretical analysis and re-conceptualization. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2010, 20, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, T.F.; Guillen, M. Organizational commitment: A proposal for a wider ethical conceptualization of ‘normative commitment’. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 78, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Herscovitch, L. Commitment in the workplace: Toward a general model. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2001, 11, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, R.W. Differentiating organizational commitment from expectancy as a motivating force. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1981, 6, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, M.B.; Janoff-Bulman, R.; Cotter, J. Perceiving value in obligations and goals: Wanting to do what should be done. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 982–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Fan, B. Effect of an agency’s resources on the implementation of open government data. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, B.M.; Jung, D.I. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1999, 72, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Q.; Weng, Q.; Jiang, Y. When does affective organizational commitment lead to job performance?: Integration of resource perspective. J. Career. Dev. 2020, 47, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansky, J.W.; Cohen, D.J. The relationship between organizational support, employee development, and organizational commitment: An empirical study. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2001, 12, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskes, I. Relationship between leadership styles and dimensions of employee organizational commitment: A critical review and discussion of future directions. Intang. Cap. 2014, 10, 26–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Open Data Index. Available online: http://ifopendata.fudan.edu.cn/ (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J.; Smith, C.A. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.; Volberda, H.W. Managing potential and realized absorptive capacity: How do organizational antecedents matter? Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balasubramanian, N.; Lee, J. Firm age and innovation. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2008, 17, 1019–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Sapienza, H.J.; Almeida, J.G. Effects of age at entry, knowledge intensity, and imitability on international growth. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.A. Innovation, firm size, and firm age. Small Bus. Econ. Group 1992, 4, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Slevin, D.P.; Covin, J.G. Strategy formation patterns, performance, and the significance of context. J. Manag. 1997, 23, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.; Junni, P. A contingency model of CEO characteristics and firm innovativeness: The moderating role of organizational size. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Atuahene-Gima, K. The adoption of agency business activity, product innovation, and performance in Chinese technology ventures. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, A.F. PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling [White Paper]. 2012. Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Kaasenbrood, M.; Zuiderwijk, A.; Janssen, M.; de Jong, M.; Bharosa, N. Exploring the factors influencing the adoption of open government data by private organisations. Int. J. Public Adm. Digit. Age 2015, 2, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Le, P.B. How transformational leadership facilitates radical and incremental innovation: The mediating role of individual psychological capital. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2020, 12, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Zeng, X. Does transactional leadership count for team innovativeness? The moderating role of emotional labor and the mediating role of team efficacy. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2011, 24, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, A.N.; van Knippenberg, D.; Schippers, M.; Stam, D. Transformational and transactional leadership and innovative behavior: The moderating role of psychological empowerment. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riketta, M. Attitudinal organizational commitment and job performance: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bučiūnienė, I.; Škudienė, V. Impact of leadership styles on employees’ organizational commitment in lithuanian manufacturing companies. South East Eur. J. Econ. Bus. 2008, 3, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bycio, P.; Hackett, R.D.; Allen, J.S. Further assessments of Bass’s (1985) conceptualization of transactional and transformational leadership. J. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Effects of leadership and leader-member exchange on commitment. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 2005, 26, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.J.; Lee, A.; Tian, A.W.; Newman, A.; Legood, A. Leadership, creativity, and innovation: A critical review and practical recommendations. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Number (N = 239) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 142 | 59.41% |

| Female | 97 | 40.59% |

| Age | ||

| <25 years | 9 | 3.77% |

| 26–35 years | 151 | 63.18% |

| 36–45 years | 69 | 28.87% |

| >45 years | 10 | 4.18% |

| Education Level | ||

| Senior high school or below | 1 | 0.42% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 181 | 75.73% |

| Master’s degree or above | 57 | 23.85% |

| Position Level | ||

| Senior level | 80 | 33.47% |

| Middle level | 159 | 66.53% |

| Role in the OGD-Driven Innovation | ||

| R&D | 98 | 41% |

| Sales | 48 | 20.08% |

| Administration | 93 | 38.91% |

| Measure | Sample Item | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformational Leadership | TFL1 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.56 |

| TFL2 | 0.72 | ||||

| TFL3 | 0.72 | ||||

| TFL4 | 0.73 | ||||

| TFL5 | 0.74 | ||||

| TFL6 | 0.80 | ||||

| TFL7 | 0.76 | ||||

| Transactional Leadership | TAL1 | 0.65 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.54 |

| TAL2 | 0.68 | ||||

| TAL3 | 0.70 | ||||

| TAL4 | 0.74 | ||||

| TAL5 | 0.79 | ||||

| TAL6 | 0.83 | ||||

| TAL7 | 0.75 | ||||

| Affective Commitment | AC1 | 0.74 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.63 |

| AC2 | 0.81 | ||||

| AC3 | 0.78 | ||||

| AC4 | 0.78 | ||||

| AC5 | 0.82 | ||||

| AC6 | 0.82 | ||||

| Normative Commitment | NC1 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.57 |

| NC2 | 0.74 | ||||

| NC3 | 0.84 | ||||

| NC4 | 0.76 | ||||

| NC5 | 0.79 | ||||

| NC6 | 0.74 | ||||

| OGD-Driven Radical Innovation | OGD_RI1 | 0.74 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.52 |

| OGD_RI2 | 0.72 | ||||

| OGD_RI3 | 0.73 | ||||

| OGD_RI4 | 0.68 | ||||

| OGD-Driven Incremental Innovation | OGD_II1 | 0.81 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.68 |

| OGD_II2 | 0.81 | ||||

| OGD_II3 | 0.81 | ||||

| OGD_II4 | 0.87 |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. TFL | 5.77 | 0.77 | 1 (0.75) | ||||||

| 2. TAL | 4.68 | 0.81 | 0.24 ** | 1 (0.73) | |||||

| 3. AC | 5.55 | 0.90 | 0.37 ** | 0.15 * | 1 (0.79) | ||||

| 4. NC | 5.04 | 0.88 | −0.01 | 0.17 ** | −0.01 | 1 (0.75) | |||

| 5. OGD_RI | 5.71 | 0.82 | 0.47 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.12 | 1 (0.72) | ||

| 6. OGD_II | 4.62 | 0.93 | 0.08 | 0.30 ** | 0.17 * | 0.42 ** | 0.25 ** | 1 (0.82) | |

| 7. OGD_AS | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.07 | 0.36 ** | −0.01 | 0.28 ** | 1 |

| Variables | DV = Affective Commitment | DV = OGD-Driven Radical Innovation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| (Constant) | 2.53 ** | 0.65 | 2.55 ** | 0.54 |

| Firm’s age | −0.12 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| Firm’s size | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.07 |

| Know | 0.05 | 0.13 | −0.07 | 0.10 |

| Industry | −0.04 | 0.10 | −0.11 | 0.08 |

| Hostility | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| Capacity | 0.47 ** | 0.09 | 0.27** | 0.08 |

| Sample’s age | 0.12 | 0.07 | −0.08 | 0.05 |

| Province | −0.09 | 0.10 | −0.07 | 0.07 |

| TFL | 0.19 * | 0.09 | 0.20 ** | 0.07 |

| OGD_AS | −0.24 * | 0.11 | ||

| TFL × OGD_AS | −0.53 ** | 0.17 | ||

| AC | 0.43 ** | 0.08 | ||

| R^2 | 0. 39 ** | 0.56 ** | ||

| Variables | DV = Normative Commitment | DV = OGD-Driven Incremental Innovation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| (Constant) | 4.40 ** | 0.71 | 1.47 * | 0.72 |

| Firm’s age | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Firm’s size | 0.00 | 0.10 | −0.07 | 0.08 |

| Know | −0.23 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| Industry | −0.04 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.11 |

| Hostility | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| Capacity | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.18 * | 0.08 |

| Sample’s age | 0.13 | 0.09 | −0.09 | 0.10 |

| Province | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.11 |

| TAL | 0.17 * | 0.08 | 0.22 * | 0.08 |

| OGD_AS | 0.56 ** | 0.12 | ||

| TAL × OGD_AS | 0.37 * | 0.14 | ||

| NC | 0.39 ** | 0.07 | ||

| R^2 | 0.20 ** | 0.28 ** | ||

| Indirect effect of TFL × OGD_AS on OGD_ RI via OC | Indirect effect of TAL × OGD_AS on OGD_II via OC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | OGD_AS | Effect | SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Effect | SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| AC | Initial Stage | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.06 |

| Mature Stage | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.19 | 0.08 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.01 | |

| NC | Initial Stage | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.00 | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.07 |

| Mature Stage | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.26 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, M.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, M.; Li, G. How Leadership Influences Open Government Data (OGD)-Driven Innovation: The Mediating Role of Organizational Commitment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021219

Zhou M, Wang Y, Jiang H, Li M, Li G. How Leadership Influences Open Government Data (OGD)-Driven Innovation: The Mediating Role of Organizational Commitment. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021219

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Mingle, Yu Wang, Hui Jiang, Min Li, and Gang Li. 2023. "How Leadership Influences Open Government Data (OGD)-Driven Innovation: The Mediating Role of Organizational Commitment" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021219