Abstract

Many studies have shown that credit is crucial for the adoption of new agricultural inputs and technologies in developing countries. Hence, the issue about how financial institutions select farmer applicants to give loans to is very important. We used primary data from 401 rural households to show what kinds of farmers can get credit from banks in Sudan. The probit model is used to examine the factors that determine both farmers’ access to credit and the adoption of new inputs, and to show the nexus of credit accessibility and the adoption of new input through other factors. The main findings show that farming experience, the number of close friends, hire labor, cultivated land, irrigation, and extension services, are the factors that significantly determine farmers’ credit accessibility from banks. Some of these determinants, such as cultivated land and irrigation, also influence the adoption of new inputs. There exists a strong correlation between credit accessibility from banks and the possibility of using new input. In addition, an IV probit model shows that farmers’ use of chemical fertilizers and improved varieties directly influences the loan decision from banks. This means farmers’ credit demand induced by the chance of using new input actually has been satisfied by the banks in Sudan. The comparison results show that, for the subsample, for the Farmer’s Commercial Bank (FCB) the nexus between credit accessibility and the adoption of new inputs is stronger than that of the Agricultural Bank of Sudan (ABS). Therefore, this study recommended that the Sudan government should choose FCB as the lender of subsidized credit to increase the banks’ contribution to the development of plant production.

1. Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 1 and 2 call for eradicating global poverty and creating a world free of hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition. Seven years have passed since all UN member states adopted this in 2015. Nevertheless, it is estimated that as of 2018, more than 820 million people are still hungry, mostly in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), Latin America, and Asia [1]. One of the goals of sustainable development is to double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small food producers, partly by improving access to financial services, including credit [2]. In this context, the agricultural sector in developing nations has received significant attention to enhance food production. Given the rapid development and worldwide population expansion, food (in)security will become the greatest barrier to global sustainable development if major steps to increase food supply are not implemented. As a result, it is critical to pay close attention to farmers, who are the key participants in agriculture, and issues impeding agricultural intensification [3,4]. Agriculture is now considered an industry in rural areas and urban areas [5,6]. Moreover, agricultural production still accounts for a large share of rural areas and contributes to the employment of the majority of workers [7].

Like many developing countries, Sudan relies heavily on the agricultural sector; almost 65 percent of the population is employed in agriculture, which is the main supplier of raw materials for industry. It accounts for 20 percent of the GDP in 2020. Around 175 million feddans (73.5 million ha) are suitable for agriculture, and the average cultivated area is only about 26 million ha [8]. Although the sector includes family farms ranging from 2 to 50 hectares for income generation and subsistence [9], the poverty rate is 56% [10] due to low land productivity. Primitive technologies prevail in Sudan’s agriculture. Local crop varieties have low yield potential; most crops are grown under rainfed conditions, irrigated, used only in limited areas, and have little or no fertilizer [11]. Thus, the adoptions of agricultural technologies are crucial to follow precision agriculture.

The ability to escape the poverty trap in many emerging nations, such as Sudan, relies on the evolution and development of the agricultural sector. Agricultural progress and development are impossible without technological options for increasing productivity [12]. Agricultural development is essential for reducing poverty and guaranteeing food security in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) in general and Sudan in particular; nonetheless, agricultural production has increased slowly in the region. Low adoption rates of new technologies, such as improved varieties, chemical fertilizers, and enhanced agronomic methods, are contributing factors [13,14]. Emerging nations face two significant obstacles: guaranteeing food security and reducing poverty. Agricultural output development is essential for enhancing the well-being of small-scale farmers in these nations. With a fast-rising population and limited arable land, technological intervention in agriculture appears to be the only realistic alternative for emerging nations to feed the growing population and produce employment [12,15]. Increasing the adoption of new agricultural technologies can be an important option for ending hunger and food insecurity by helping farmers increase crop productivity, lower food prices, and make more food available to poor households. Moreover, promoting the adoption of improved crop varieties sustainably can help improve household welfare [16,17,18,19].

Agricultural finance plays a vital role in the modernization and commercialization of farming in rural economies [20,21]. Notably, new agricultural technologies are essential for national and economic growth. Their usage in rural economies is only conceivable if farmers have access to financing to acquire contemporary technical inputs [22]. However, in developing countries such as Sudan, rural household farmers have inadequate access to credit services to adopt technologies and improve their productive capacity. Despite the high demand for financial services in rural areas, financial service providers, such as banks and microfinance institutions, are generally reluctant to provide services in rural areas due to the precarious nature of agricultural production [23]. However, poor and low-income households often lack sufficient collateral, which prevents them from borrowing according to their income and limits their access to formal credit [4,24]. Therefore, a lack of access to financing is often perceived as one of the constraints to agricultural technology adoption [25]. Traditional banks are reluctant to provide credit to low-income households without sufficient collateral due to high transaction costs and erroneous information [26]. Thus, smallholder farmers may be unable to invest in new technologies or profitable business activities [7,27]. Farmers in developing nations mainly rely on the formal and informal credit sectors due to a lack of savings. According to the production and financial structure hypothesis, farm families with limited financial resources may operate more productively overall if they had access to loan options [28]. Hence, this study attempts to analyze the determinants of credit access and agricultural technology adoption among rural households in the context of Sudan. In this article, we used the primary data of 401 rural households and the probit model is applied to estimate the data. In addition, this paper also attempts to give answers of following research questions: (1) What kinds of farmers can get credit from the banks, or what kinds of farmers would be more likely chosen as borrowers by the banks in Sudan? (2) Are the farmers who are more likely to adopt new inputs also the ones preferred by banks? Has farmers’ credit demand, induced by new inputs use, been well satisfied by the banks?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Access to Credit and Chemical Fertilizers Nexus

Chemical fertilizers are the most important inputs in achieving high and rapid rates of agricultural return. For example, one kilogram of nutritional fertilizers yields around 8 kg of grain. Fertilizers are often regarded as equally essential, accounting for up to 50% of the production increase [22]. Thus, fertilizers usage is crucial in increasing and maintaining agricultural production in developing countries.

Various researchers have worked in different regions of the world on the impact of formal credit access on household adoption of agricultural technologies. In Burkina Faso, Combary [29] utilized a tobit model to examine factors influencing farmers’ decisions to adopt and intensify the use of chemical fertilizers. The empirical findings revealed that access to finance had a substantial positive effect on the likelihood of chemical fertilizers adoption. Bosede Sekumade [30] investigated the economic impact of organic and inorganic fertilizers on maize output in Nigeria; the results showed that access to credit was related to other characteristics that determined the organic fertilizers’ use. Besides, Nakano and Magezi [13] performed a randomized control trial (RCT) to investigate the influence of credit on technology adoption and rice production. The findings indicated that credit did not boost fertilizer use by individuals with greater accessibility to irrigation water since they had previously applied the appropriate quantity of fertilizers. In the context of Ethiopia, Croppenstedt et al. [31] applied a double-hurdle fertilizer adoption model to examine why farmers did not purchase fertilizers. The findings supported the notion that access to credit is a key supply-side barrier to fertilizers adoption and that family financial resources were typically insufficient to fund fertilizers expenditures. In rural Ethiopia, Tadesse [32] also investigated the link between fertilizer adoption and credit; the results showed that improved access to credit increased the likelihood and intensity of fertilizer use substantially.

On the other hand, Ouattara et al. [33] used the IV-probit and IV-tobit models to investigate the relationship between rice farmers and credit. The results showed that increasing credit by XOF 100 could increase the amount of fertilizers used by 2.70 kg. In the case of Kenya, Njeru et al. [34] used household-level survey data to investigate the role of credit access in improving rice production. The study revealed that credit accessibility played an essential role in assisting farmers in acquiring fertilizers and other purchased inputs, which would have impeded the high yields observed in the Mwea irrigation scheme. Similarly, Ogada et al. [35] stated that a lack of credit influences farmers’ adoption of inorganic fertilizers and enhanced maize varieties. In Pakistan, according to Ali et al. [36], access to credit facilities was beneficial and significant, showing that families with access to credit facilities increased fertilizers dosages.

2.2. Access to Credit and Improved Varieties Nexus

Most smallholder farmers, especially in developing countries, rely on self-saved seed or seed from local sources, which are generally tainted with pests and diseases that considerably lower field crop production. Indeed, the usage of poor-quality seeds has been linked to the present low yields on smallholder farms, which range between 8 and 10 tons per hectare, compared to 20–30 tons per hectare in more industrialized countries [37]. Thus, one of the most significant factors in improving agricultural productivity in any farming system in developing countries is using high-quality seeds.

Several empirical studies have investigated the link between credit access and improved usage of varieties. For instance, Ouma et al. [38] examined the factors impacting the adoption and intensity of improved seeds and fertilizer using the logit and tobit models. Logit regression findings indicated that credit accessibility positively and substantially affected improved maize variety and fertilizer adoption. On the other hand, tobit’s model findings showed that access to finance had a substantial effect on the degree of usage of enhanced maize varieties and fertilizer in the case of Kenya. Likewise, Obuobisa-Darko [39] investigated the effect of credit accessibility and other variables on adopting cocoa-approved technologies using a logistic regression model. The findings revealed that credit access had a significant impact on technology adoption.

Similarly, Simtowe et al. [40] found that farmers with access to financial services were more likely to cultivate at least one improved pigeon pea variety. These findings highlight the need to increase smallholders’ access to credit markets to facilitate their purchase of improved varieties. Furthermore, Letaa et al. [41] assessed the adoption and spatial distribution of enhanced common bean varieties using a bivariate probit model. They reported that access to credit significantly affected the adoption of improved varieties in conjunction with variables. Alike, access to finance is found to have a positive and significant effect on the log odds of adopting improved maize varieties, suggesting that farmers who had access to credit were more likely to adopt improved maize varieties than those who did not [18,42,43]. Additionally, access to financing positively impacted the extent to which farmers adopted better cassava varieties [44,45].

Using the tobit model, Milkias [46] examined the parameters influencing the intensity of adopting high-yielding teff by Ethiopian smallholder farmers. It revealed that financing accessibility positively and significantly affected the likelihood of adopting high-yielding teff types. As a result, credit accessibility is regarded as a critical factor in the adoption of new technology. According to Chandio and Jiang [47], wheat producers with access to financing were more likely to adopt enhanced wheat varieties than those without. According to Abdul-Rahaman et al. [48] and Chandio and Yuansheng [16], access to credit had a favorable and substantial marginal influence on enhanced rice variety adoption.

Similarly, Abebe et al. [49] found that credit accessibility is integral in adopting improved potato varieties in Ethiopia. In the context of Bangladesh, Jimi et al. [50] assessed the impact of credit accessibility on overall rice farmers’ productivity and separated the entire effect from technical change. The findings suggested that credit accessibility considerably boosted the adoption of hybrid rice varieties. Additionally, Obisesan et al. [51] investigated the impact of loan access and technology adoption on cassava household production and income in the case of Nigeria, and they found a higher degree of adoption and an impact of improved cassava technology on individuals who had access to credit. More recently, Mugumaarhahama et al. [52] showed that credit access influences smallholder farmers’ adoption of improved sweet potato varieties.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

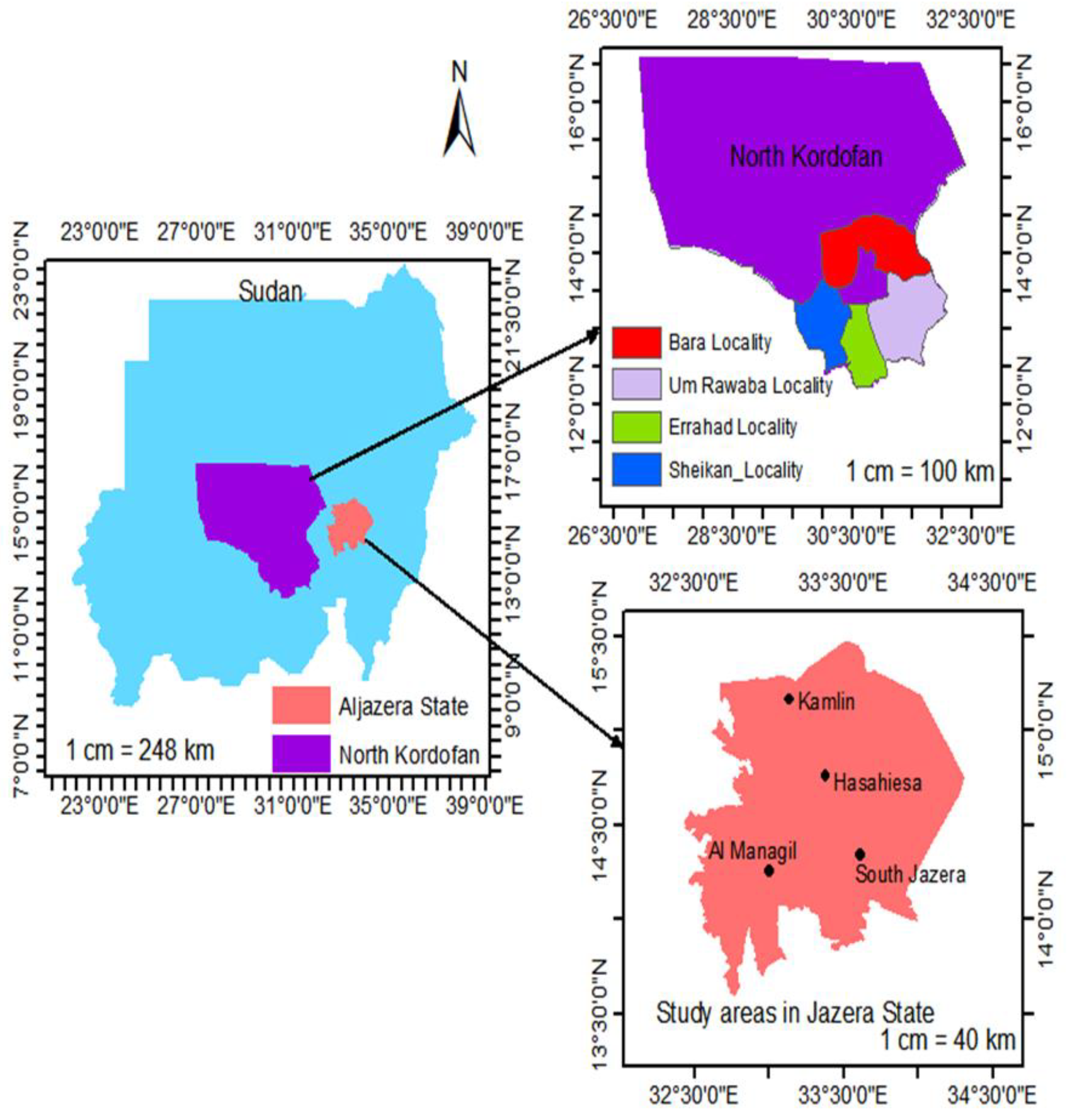

This study was done in two regions, North Kordofan State and Al Jazera Scheme in Sudan (see Figure 1). Because credit is not widely available among Sudanese rural farmers, we were forced to concentrate our efforts in the areas with the best access to credit. We chose the Al Jazera scheme because it is the most important agricultural irrigation. The government places a high value on this region due to its significant contributions to the irrigated agricultural sector. As a result, farmers have good access to credit.

Figure 1.

Map of the research area.

Similarly, North Kordofan state is critical as a rain-fed agricultural area, and farmers have good access to financing, so we chose this area because of its importance in the rain-fed agricultural sector. In fact, there are some areas where farmers have access to credit, but we initially focused on these two areas due to financial constraints.

North Kordofan State is situated in central Sudan, roughly 990 km from Khartoum’s capital. It is located between the latitudes of 13°36′00″ and 14°00′00″ N and the longitudes of 27°55′07″ and 28°38′11″ E. It spans two climate belts, corresponding to the two main east-west trending climatic zones in Sub-Saharan Africa. The northern region is semi-arid, and the southern stretch is low-lying Savannah. The area has low relief and an undulating topographical surface owing to the prevalence of dunes [53,54]. June through September is the wet season. Rainfall rises from 100 mm per year in the far north to 200 mm in the intermediate zone and 350 mm in the south, albeit rainfall is erratic, with substantial variations between years.

In contrast, the Al Jazera Scheme is situated in a semi-arid zone south of Khartoum, between the Blue and White Nile Rivers. The plan began in 1911 when an experimental farm was constructed in Tayba hamlet on the Blue Nile’s west bank. The plan, which spans 880,000 hectares (ha), is one of the biggest in the area [55]. Cotton, wheat, sorghum, groundnuts, and vegetables are the principal crops grown by each farmer, who has 8.4 hectares (on average) split into four plots [56]. The Jazera system is situated in a hot, semi-arid environment. Winter from November to February, summer from April to May, and fall from July to September are separate seasons, with March, June, and October serving as transitional months. Rainfall intensifies from north to south [56].

3.2. Data and Sampling

A comprehensive qualitative study was undertaken from May to July 2022 through semi-structured in-depth interviews with farming households. Four hundred respondents were picked at random from two areas. The primary author gathered the data via face-to-face interviews using a set of pre-designed questions. The created questionnaire was administered in advance to eliminate any ambiguity. Based on the pre-test survey, changes were made to the final questionnaire. The questionnaire included questions about farmers’ sources of credit, access to information on sources of credit, institutional factors, socio-economic conditions, and agricultural technology adoption. The sampled respondents either borrowed from the Agricultural Bank of Sudan or the Farmer Commercial Bank. Regarding technology adoption, we asked farmers specific questions about the technologies they have adopted in the past three years. All farmers who adopted chemical fertilizers or improved varieties were considered adopters. The multi-stage sampling approach was used to collect the sample. In the first stage, Norther Kordofan State and the Al Jazera scheme were chosen. Taking these regions somehow covers the nation at large beneficiaries of those with better credit access. In other regions, household farmers have less access to credit from banks compared to each other. Four localities in each selected region were randomly chosen for stage two. These localities include Bara locality, Um Ruwaba locality, Errahad locality and Sheikan locality in the North Kordofan region, Kamlin locality, Hasahiesa locality, South Jazera locality and Al Managil locality in the Al Jazera region. During stage three, we randomly selected 48 villages of rural household farmers.

3.3. Empirical Model

The probit regression assumes the existence of a potential, unobserved continuous variable Y* that controls the value of the variable Y, although we can only observe values of 0 and 1. Realistic probabilities and a credible error term distribution are two additional benefits of the probit model. According to Aldrich and Nelson [57], probit analysis presupposes the existence of a theoretical index Y* that is specified by the following regression association:

where : credit accessibility, Represent the explanatory variable for the observation , Represent the parameter for the variable , Represents the error term of the observation . This study assumes that credit accessibility is a dichotomous choice, meaning that a household farmer will either get credit or not. Therefore, a farmer is expected to get credit access for the greatest marginal benefits. Let serve as a metric for accessibility, with 0 denoting no accessibility and 1 denoting accessibility. A probit regression model, as defined by Gujarati [58], can be used to estimate if the error term is assumed to have a normal distribution. In order to examine the variables affecting household farmers’ access to credit from banks and adoption of new technology, we will use the probit model.

In this study, problems with possible endogeneity are solved with the instrumental variable method. the adoption of chemical fertilizers and improved varieties are instrumented by the ratio of adopters for other observations in the same village.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

Table 1 presents the summary statistics of the variables considered in the study. It reveals that 199 farmers (49.6%) have already got credit and another 30 farmers (49.6%) believe the banks have high chance to give them credit if they have applied for. In all, 124 farmers (30.9%) received their credit from ABS, 76 farmers (19.0%) obtained their credit from FCB, while only one of them acquired credit from both banks. This is because ABS has more locations than FCB, with 11 ABS locations spread across the state of Al Jazera. In the state of North Kordofan, seven locations are dispersed throughout the localities’ centers. Al Jazera state has six FCB locations, while North Kordofan has only two. About 65% of rural household farmers have a bank account. The average distance from the villages to the nearest ABS and FCB are 26.33 and 58.01 km, respectively. This means the branches of various banks are far from surveyed households. About 96% of the rural household head is in charge of agricultural production.

Table 1.

Data and description of variables.

Men make up 98% of farmers. The average farmer was 50, with a farming experience of 27 years. It shows that farmers are still in their productive age with a lot of experience in agriculture. The average level of formal schooling for farmers is nine years demonstrating a significant formal education regarding the government policies, banking transactions, and new technologies. The average land ownership by a household is about 17.3 hectare, with the average of current cultivated land and land that can be irrigated being 17.1 and 5.1 hectare, respectively. It is assumed that family size indicates the amount of available labor within the family. The distribution of sample responses in the research region indicates that the average family size is around seven members per household, and the average number of family workers per household is three. Besides, the highest education of agricultural workers is 11.24 years of schooling. Despite the importance of extension contacts in increasing household access to knowledge on new or improved farm technology, only approximately 25% of rural households got extension services.

In comparison, only about 19% obtained formal agricultural training. However, about 56% and 63% of rural households adopted chemical fertilizers and improved varieties, respectively. Lending groups and cooperative societies have the potential to provide affordable credit to smallholder farmers because they can reduce the transaction cost and lower the risk and facilitate access to credit. However, the results indicate that 45.30% of rural households are in farmer group associations, and 28% have membership in cooperative societies in their villages. Farmers need information on the latest varieties, agricultural finance, crop production techniques and improved agronomic practices to produce. This could be achieved through learning from others in the villages. Based on the sample surveyed, about 62% of rural households learned from other farmers. The average number of close friends to the farmer is 35 persons. About 78% of household farmers are in good health status.

This study also uses socioeconomic factors to analyze the considerable differences between farmers in the study region who have access to finance and those who do not. Table 2 displays the descriptive outcomes of the mean differences. The findings showed that credit-accessible farmers are older, more educated, and more experienced. Almost all of them have a bank account, have a higher chance of using chemical fertilizers and improved varieties, and are healthier and more learning from others. Additionally, Table 2 displays the cultivated farmland by households with access to credit more than those without access to credit. It demonstrates that characteristics such as education, age, gender, experience, bank account, fertilizers, improved varieties, farmer organizations, membership in cooperative societies, the distance of banks, land holding size and learning from others all have a substantial impact on credit access and non-access. These results indicate that individuals with credit and those without access to credit differ systemically.

Table 2.

Comparing the mean differences between households with and without credit access from banks.

4.2. Socioeconomic Characteristics of Rural Household Borrowers between the Two Banks

Table 3 presents the frequency distribution of household characteristics between ABS and FCB borrowers in the study and shows that despite the small sample size of females surveyed, all of them (five females) do not have access to credit from both banks. This implies that men are more likely to access credit than women. Additionally, the result showed that 43 ABS borrowers (34.7%) aged in the range between 51 to 60 years. In comparison, 27 FCB borrowers (35.5%) aged between 41 to 50 years. This means that FCB beneficiaries are younger than ABS borrowers. It also indicates that both banks give preference to older farmers for loans. This conclusion contradicts the results of Chandio et al. 2021 [59] who found that as the age of a sugarcane farmer in Pakistan increases, the projected chance of getting formal financing decreases. The explanation is that most of the farmers who engaged in the agricultural sector in the study area belong to the elderly age. The distribution of education levels among borrowers at the two banks is also shown in Table 3. It demonstrates that 44 farmers (35.5%) with loan access through ABS have education levels ranging from 3 to 8 years. In contrast, 29 farmers (38.2%) of FCB lenders have educational level ranging from 9 to 11 years. This finding implies that FCB borrowers are more educated than ABS borrowers.

Table 3.

Distribution of household borrower’s characteristics between the two banks.

Regarding farming experiences, the results show that 34 creditors (27.4%) from ABS lenders have agricultural experience in the range of 31 to 40 years, while 22 creditors (28.9%) of FCB have agricultural experience in the range of 21 to 30 years. This indicates that FCB lenders have less agricultural experience compared to ABS financiers. Generally, institutional sources in the study area prefer farmers with good farming experience. This result is consistent with the result of Chandio et al. [59], who concluded that access to institutional agricultural credit is strongly linked to having experience in farming. As shown in Table 3, only 29 ABS and 14 FCB borrowers have received formal agricultural training. In contrast, only 45 ABS financiers and 20 FCB creditors have received extension services from 124 household farmers. These results mean both formal training and extension services are not predominant among household farmers. Likewise, the results showed the distribution of household family members of creditors; 70 ABS creditors (56.5%) out of 124 households had large family sizes ranging between six to 10 members. At the same time, 47 FCB borrowers out of 76 household (61.9%) are in the same family-size categories. Regarding the number of family laborers, results show that most household farmers in both family workers in the same category; 113 ABS creditors out of 124 household (91.1%) had one to five family laborers. At the same time, 67 FCB creditors out of 76 household (88.2%) had the same categories of family labor. Additionally, the result shows that most ABS and FCB borrowers are in charge of agricultural production. Further, most of the borrowers from both banks have good health. In addition, the results presented in Table 3 revealed the distribution of the number of close friends to the household farmer; the result indicated that 44 ABS creditors and 37 FCB borrowers have close friends above 40 persons. This implies that farmers in the study area have a good social network. Additionally, the results show that most ABS and FCB borrowers have bank accounts, adopt chemical fertilizers, improve varieties, have cooperative membership, have farmers’ groups, and learn from others. The distribution of the highest education of laborers who do agricultural work is presented in Table 2. The results showed that 61 ABS farmers out of 124 households have educational levels between 11 to 15 years. At the same time, 29 FCB creditors out of 76 household years of schooling ranged in the same category. Concerning land holding size, the results demonstrate that 93 ABS creditors out of 124 household (75%) had land sizes ranging from 1 to 21 hectares, while 45 FCB creditors out of 76 household (59.2%) fell into this category. This finding indicates that the landholding size is important for obtaining formal credit from both banks. This finding is conformity with the findings of Saqib et al. [60], who discovered a strong and positive link between loan accessibility and landholding size. Likewise, the result showed that about 94 ABS borrowers cultivated land between 1 to 21 hectares, and 45 FCB borrowers belonged to the same size of cultivated land. In addition, irrigation for both banks’ borrowers’ range between 1 to 13 hectares.

4.3. Summary of Statistics of Borrowers, Non-Borrowers, and Borrowers from Two Banks

Table 4 depicts the descriptive statistics between household farmers without access to credit, those with access to credit, those with access to credit from ABS and FCB, and those who have adopted new technology. The results from Table 4 showed that 43% of farmers who did not receive credit adopted chemical fertilizers, while 50% adopted improved varieties. For those with access to credit, the results showed that 70% of household farmers adopted chemical fertilizers, and 76% adopted improved varieties. This result indicates that those with access to credit are more likely to adopt new technology than those without credit access. Additionally, the results showed that 68% of ABS borrowers had adopted chemical fertilizers, and 74% adopted improved varieties. In contrast, 75% of FCB borrowers have adopted chemical fertilizers, while 79% have adopted improved varieties. Comparing ABS and FCB borrowers, we find that FCB borrowers have higher adoption than ABS borrowers.

Table 4.

Adoption of new technology for borrowers and non-borrowers.

4.4. Empirical Results

A probit regression model is applied to examine the factors determining a famer’s credit accessibility and the factors determining whether use new inputs simultaneously. Credit accessibility is measured by whether a farmer has obtained credit from the banks and would obtain credit if he has applied (self-reported by famers).

Table 5 summarizes the results from the probit estimation for the rural farmers who have obtained credit access. Six variables significantly determined farmers’ access to credit from the agricultural bank of Sudan and farmer’s commercial bank. Whereas five variables are associated with the decision to use chemical fertilizer or not, three variables are related to the adoption of improved varieties. The household farmer’s experience is significant at 10%. The experience coefficient is positive, indicating that farmers with more years of farming experience are more likely to be able to obtain credit. This result is in line with Saqib et al. [60], who concluded that farmers with more experience had more credit options than farmers with less experience. The number of close friends to the household farmer positively affects access to credit. The coefficient on the number of close friends is positive and significant at 10%. This implies that farmers with good social networks are more likely to apply for agricultural credit. Similarly, the results showed that hiring laborers is related to credit access. This means that small farmers and their families may cultivate their fields. Thus, they provide the labor required for farming themselves. However, medium and large farmers hire farm laborers to work on their fields, therefore access to credit matters. Additionally, the study results show a positive and significant relationship between cultivated land and access to agricultural credit from the banks, which implies that land is the most effective and widely accepted form of collateral. Many renters and landless people are barred from participating in the formal credit markets because they lack collateral. Therefore, this finding suggests that land-owning household farmers are more likely to obtain bank credit. The result of our study are agrees with Saqib et al. [6] and Saqib et al. [60], who argued that farmers who own a large plot of land are more likely to obtain loans from both formal and informal sources. Likewise, irrigation is positively and significantly associated with farmers’ access to formal credit. Additionally, the variable of extension services is positive and significantly associated with household farmers’ access to agricultural credit from the banks. This result indicates that farmers receiving extension services have a higher chance of obtaining credit access from the banks.

Table 5.

Econometric estimates of probit model for the farmer access to credit and adoption of new technology.

Regarding the adoption of chemical fertilizers, the results show that the variable of cultivated land is one factor that significantly influences household farmers to adopt chemical fertilizers. Further, irrigation also has a positive and significant association with farmers adopting chemical fertilizers. This result implies that farmers who have irrigable land and use irrigation water have a higher probability of adopting chemical fertilizers. Our result is consistent with [61,62], who reported that where it was found that farmers in China and Ethiopia were more likely to adopt chemical fertilizers if they had access to irrigation. Additionally, the variable of farmer group associations is positive and statistically significant with farmers’ adoption of chemical fertilizers, which indicates that if the household farmers are in farmer organizations they are more likely to adopt chemical fertilizers. This may explain why farmers in groups share their knowledge about new technology with each other.

In contrast, the results showed that the variable of membership in cooperative societies is statistically significant and negative with farmers’ adoption of chemical fertilizers. This means that farmers who have membership in cooperative societies are less likely to use chemical fertilizers. This may explain that the study area’s cooperative societies are not effectively influencing their members to use chemical fertilizers. Furthermore, the results show that the household’s health status is statistically significant and negative at the 10% level. This finding implies that farmers in good health are less likely to use chemical fertilizers. The result of our study are contradicts the findings of Abebe and Debebe [63], who argued that a better health status of the household head increases the likelihood of using organic fertilizer in Ethiopia. Because of their lack of knowledge about chemical fertilizers, farmers in the study area may fear the health risks associated with their use.

Concerning the adoption of improved varieties, the study’s results showed that the education level of household farmers is positive and significantly associated with farmers’ use of improved varieties. This means that farmers with a good level of education are more likely to adopt new technology than uneducated farmers. The educational level coefficient is significant at 5%. Likewise, the decision to use improved varieties is positively correlated with the variable of formal agricultural training. At 5%, the training coefficient is positive and significant. This indicates that agricultural training increases farmers’ probability of adopting improved varieties. Similarly, farmers’ adoption of improved varieties is found to be positively and significantly affected by the variable of irrigation, which implies that farmers who grow under irrigation have a higher probability of using improved varieties. This may be because the improved varieties required good land and good irrigation.

The Sheikan locality was used as a reference category for farmers’ locations in the study. The results show that the probability of farmers using chemical fertilizers is higher in Bara locality (North Kordofan state) and in Al Managhil, Al Hasahiesa, South Jazera, and Al Kamlin (Al Jazera state). This result indicates that the farmers in Al Jazera region are more likely to use chemical fertilizers and improved varieties than in North Kordofan region.

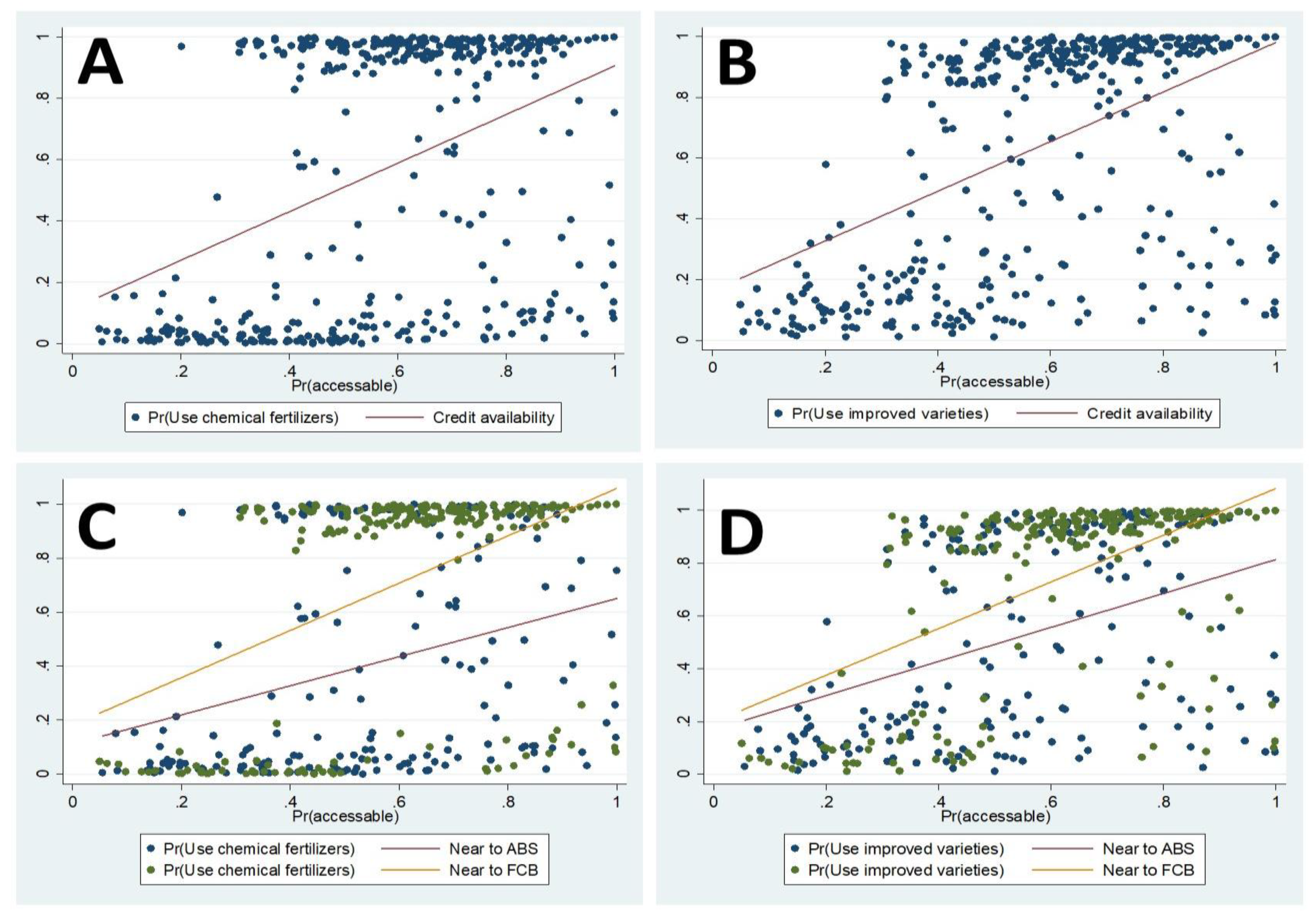

Regarding the nexus between credit accessibility and the adoption of chemical fertilizers, Figure 2a depicts a strong relationship between credit accessibility and the adoption of chemical fertilizers. Furthermore, the correlation between credit accessibility is (0.50) and statistically significant at the 1% level. Similarly, there is a strong relationship between credit accessibility and the use of chemical fertilizers. Figure 2b shows that the correlation between credit accessibility and the use of improved varieties is (0.41) and statistically significant at the 1% level. The results mean the farmers preferred by banks to give credit also the ones who are more likely to adopting new input. Banks in Sudan do a good job in choosing the “right” farmers who have the potential to adopt new input.

Figure 2.

Nexus between credit accessibility and adoption of new inputs. (A) Chemical fertilizers. (B) Improved varieties. Nexus near to the two banks. (C) Chemical fertilizers. (D) Improved varieties.

The nexus between credit accessibility and the adoption for the sample near different banks are different. Both Figure 2c,d shows that the nexus near ABS is smaller than FCB. The correlation between credit accessibility and chemical fertilizer adoption is 0.31 for the sample more near ABS and 0.46 for the sample more near FCB. And the correlation between credit accessibility and improved varieties adoption is 0.41 for near ABS sample and 0.54 for near FCB sample. These results indicate that FCB do a better job in in choosing the “right” farmers who has the potential to adopt new input.

4.5. IV Estimation Results for the Impact of Adoption on Becoming a Borrower of Banks

Table 6 present the results of IV estimation for the impact of a farmer’s new inputs adoption on becoming a borrower of banks. The adoption of chemical fertilizers and improved varieties are instrumented by the ratio of adopters for other observations in the same village. The result showed that for the total sample, adoption of chemical fertilizers and improved varieties increase the probability of becoming a borrower of banks. This means farmers’ credit demand induced by the chance of using new input actually has been satisfied by the banks in Sudan.

Table 6.

IV-probit results for the influence of adoption on borrowers.

Furthermore, for the subsample near to ABS, the result showed that the coefficient is positive but smaller and statistically insignificant; likewise, for the subsample near to FCB, the results showed that the adoption of chemical fertilizers and improved varieties more insignificantly increase the farmer’s possibility to becoming borrowers of banks. These results also imply that the FCB do a better job in terms of satisfying farmers’ credit demand for new input adoption than ABS does.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Access to credit and financial services is important for improving the prosperity of rural households, especially in promoting agricultural development in developing countries such as Sudan. Therefore, this study analyzed the determinants of credit access from two different banks and the contribution of these banks to the diffusion of agricultural technology adoption among rural households. In general, our findings indicate that rural household farmers in the study region have limited access to finance. The results drawn from the probit regression model concluded that the farming experience, the number of close friends, hire labor, cultivated land, irrigation, and extension services, are the factors that significantly determine farmers’ credit accessibility from the banks. Additionally, our findings concluded that the cultivated land, irrigation, farmers’ group associations, membership in cooperative societies, and health status, are the factors that significantly influence household farmers’ decision to adopt chemical fertilizers. In addition, the result concluded that the main factors influencing household farmers to adopt improved varieties are educational level, formal agricultural training, and irrigation.

Concerning the nexus between credit accessibility and the adoption for the sample near different banks, we find that the nexus near ABS is smaller than FCB. The correlation between credit accessibility and chemical fertilizer adoption is 0.31 for the sample more near ABS and 0.46 for the sample more near FCB. The correlation between credit accessibility and improved varieties adoption is 0.41 for near ABS sample and 0.54 for FCB sample. This indicate that FCB can have a greater impact on agricultural technology adoption.

Based on the findings of this study, we suggest that policymakers should provide subsidies and support FCB to contribute more in terms of technology adoption diffusion among rural farmers. Likewise, institutional sources must provide adequate agricultural financing following the needs of rural families. Since access to credit increases farmers’ propensity to adopt new agricultural technology, the government should encourage banks to lend in kind. This helps farmers obtain the technology they want, such as machinery, fertilizers, pesticides, etc. Furthermore, policymakers and extension contacts should encourage farmers to join farmer organizations to enable them to access credit through the associations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.A.N. and Y.J.; methodology, Y.A.N.; software, Y.A.N.; validation, Y.A.N. and Y.J. formal analysis, Y.A.N. and M.A.; investigation, Y.J.; resources, Y.J.; data curation, Y.A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.A.N.; writing—review and editing, A.A.C. and M.O.; visualization, Y.A.N.; supervision, Y.J.; project administration, Y.J.; funding acquisition, Y.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful to NSFC for its support (Project No. 72073066 and No. 72073065), and to the sponsorship of A Project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019. Safeguarding Against Economic Slowdowns and Downturns. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca5162en/ca5162en.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Twine, E.E.; Rao, E.J.O.; Baltenweck, I.; Omore, A.O. Are Technology Adoption and Collective Action Important in Accessing Credit? Evidence from Milk Producers in Tanzania. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2018, 31, 388–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankrah Twumasi, M.; Jiang, Y.; Ntiamoah, E.B.; Akaba, S.; Darfor, K.N.; Boateng, L.K. Access to credit and farmland abandonment nexus: The case of rural Ghana. In Natural Resources Forum; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Linh, T.N.; Long, H.T.; Chi, L.V.; Tam, L.T.; Lebailly, P. Access to rural credit markets in developing countries, the case of Vietnam: A literature review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleem, I. Imperfect information, screening, and the costs of informal lending: A study of a rural credit market in Pakistan. World Bank Econ. Rev. 1990, 4, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, S.E.; Kuwornu, J.K.; Panezia, S.; Ali, U. Factors determining subsistence farmers’ access to agricultural credit in flood-prone areas of Pakistan. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 39, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Sharma, A.K. Agriculture credit in developing economies: A review of relevant literature. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2015, 7, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Special Report—2021 FAO Crop and Food Supply Assessment Mission to the Sudan. 21 March 2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc0474en (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- FAO. Special Report—2019 FAO Crop and Food Supply Assessment Mission to the Sudan. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/sudan/special-report-2019-fao-crop-and-food-supply-assessment-mission-cfsam-sudan-28-february (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- ADB. African Economic Outlook 2021: From Debt Resolution to Growth: The Road Ahead for Africa. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/afdb21-01_aeo_main_english_complete_0223.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- WorldBank. Sudan Country Economic Memorandum: Realizing the Potential for Diversified Development. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25262 (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Kassie, M.; Shiferaw, B.; Muricho, G. Agricultural technology, crop income, and poverty alleviation in Uganda. World Dev. 2011, 39, 1784–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Magezi, E.F. The impact of microcredit on agricultural technology adoption and productivity: Evidence from randomized control trial in Tanzania. World Dev. 2020, 133, 104997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Larson, D. In Pursuit of an African Green Revolution; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, S.; Norton, G.W.; Alwang, J.; Rhinehart, I.; Deom, C.M. Peanut research and poverty reduction: Impacts of variety improvement to control peanut viruses in Uganda. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2007, 89, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandio, A.A.; Jiang, Y. Factors influencing the adoption of improved wheat varieties by rural households in Sindh, Pakistan. AIMS Agric. Food 2018, 3, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, R.; Wen-chi, H.; Shrestha, R.B. Factors Affecting Adoption of Improved Rice Varieties among Rural Farm Households in Central Nepal. Rice Sci. 2015, 22, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmbando, F.E.; Baiyegunhi, L.J. Socio-economic and institutional factors influencing adoption of improved maize varieties in Hai District, Tanzania. J. Hum. Ecol. 2016, 53, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simtowe, F.; Kassie, M.; Diagne, A.; Asfaw, S.; Shiferaw, B.; Silim, S.; Muange, E. Determinants of agricultural technology adoption: The case of improved pigeonpea varieties in Tanzania. Q. J. Int. Agric. 2011, 50, 325–345. [Google Scholar]

- Claessens, S. Access to financial services: A review of the issues and public policy objectives. World Bank Res. Obs. 2006, 21, 207–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.K.; Thap, L.V.; Hoai, N.T. An application of data envelopment analysis with the double bootstrapping technique to analyze cost and technical efficiency in aquaculture: Do credit constraints matter? Aquaculture 2020, 525, 735290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Chandio, A.A.; Hussain, I.; Jingdong, L. Fertilizer consumption, water availability and credit distribution: Major factors affecting agricultural productivity in Pakistan. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awotide, B.; Abdoulaye, T.; Alene, A.; Manyong, V.M. Impact of access to credit on agricultural productivity: Evidence from smallholder cassava farmers in Nigeria. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Agricultural Economists (ICAE), Milan, Italy, 9–14 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chandio, A.A.; Jiang, Y.; Rehman, A.; Twumasi, M.A.; Pathan, A.G.; Mohsin, M. Determinants of demand for credit by smallholder farmers’: A farm level analysis based on survey in Sindh, Pakistan. J. Asian Bus. Econ. Stud. 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirkinger, C.; Boucher, S.R. Credit constraints and productivity in Peruvian agriculture. Agric. Econ. 2008, 39, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giné, X. Access to capital in rural Thailand: An estimated model of formal vs. informal credit. J. Dev. Econ. 2011, 96, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conning, J.; Udry, C. Chapter 56 Rural Financial Markets in Developing Countries. In Handbook of Agricultural Economics; Evenson, R., Pingali, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 2857–2908. [Google Scholar]

- Elahi, E.; Abid, M.; Zhang, L.; Ul Haq, S.; Sahito, J.G.M. Agricultural advisory and financial services; farm level access, outreach and impact in a mixed cropping district of Punjab, Pakistan. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combary, O.S. Decisions for adopting and intensifying the use of chemical fertilizers in cereal production in Burkina Faso. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 11, 4824–4830. [Google Scholar]

- Bosede Sekumade, A. Economic Effect of Organic and Inorganic Fertilizers on the Yield of Maize in Oyo State, Nigeria. Int. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 2, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croppenstedt, A.; Demeke, M.; Meschi, M.M. Technology adoption in the presence of constraints: The case of fertilizer demand in Ethiopia. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2003, 7, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, M. Fertilizer adoption, credit access, and safety nets in rural Ethiopia. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2014, 74, 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, N.B.; Xiong, X.; Traoré, L.; Turvey, C.G.; Sun, R.; Ali, A.; Ballo, Z. Does Credit Influence Fertilizer Intensification in Rice Farming? Empirical Evidence from Côte D’Ivoire. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njeru, T.N.; Mano, Y.; Otsuka, K. Role of Access to Credit in Rice Production in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Mwea Irrigation Scheme in Kenya. J. Afr. Econ. 2016, 25, 300–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogada, M.J.; Mwabu, G.; Muchai, D. Farm technology adoption in Kenya: A simultaneous estimation of inorganic fertilizer and improved maize variety adoption decisions. Agric. Food Econ. 2014, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Rahut, D.B.; Imtiaz, M. Affordability linked with subsidy: Impact of fertilizers subsidy on household welfare in Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello, J.; Zhou, Y.; Barker, I.; Schulte-Geldermann, E. Motivations and Mental Models Associated with Smallholder Farmers’ Adoption of Improved Agricultural Technology: Evidence from Use of Quality Seed Potato in Kenya. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2018, 31, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, J.O.; De Groote, H.; Owuor, G. Determinants of improved maize seed and fertilizer use in Kenya: Policy implications. In Proceedings of the International Association of Agricultural Economists Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, 12–18 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Obuobisa-Darko, E. Credit access and adoption of cocoa research innovations in Ghana. Res. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2015, 5, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Simtowe, F.; Asfaw, S.; Abate, T. Determinants of agricultural technology adoption under partial population awareness: The case of pigeonpea in Malawi. Agric. Food Econ. 2016, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letaa, E.; Kabungo, C.; Katungi, E.; Ojara, M.; Ndunguru, A. Farm level adoption and spatial diffusion of improved common bean varieties in southern highlands of Tanzania. Afr. Crop Sci. J. 2015, 23, 261–277. [Google Scholar]

- Feleke, S.; Zegeye, T. Adoption of improved maize varieties in Southern Ethiopia: Factors and strategy options. Food Policy 2006, 31, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MO, M.A. Analysis of adoption of improved maize varieties among farmers in Kwara State, Nigeria. Int. J. Peace Dev. Stud. 2011, 2, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Awotide, B.; Abdoulaye, T.; Alene, A.; Manyong, V.M. Assessing the extent and determinants of adoption of improved cassava varieties in southwestern Nigeria. J. Dev. Agric. Econ. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, V.; Donkor, E. Adoption of improved cassava varieties in Ghana. Agric. J. 2012, 7, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkias, D. Factors Affecting High Yielding Teff Varieties Adoption Intensity by Small Holder Farmers in West Showa Zone, Ethiopia. Int. J. Econ. Energy Environ. 2020, 5, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandio, A.A.; Yuansheng, J. Determinants of adoption of improved rice varieties in northern Sindh, Pakistan. Rice Sci. 2018, 25, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahaman, A.; Issahaku, G.; Zereyesus, Y.A. Improved rice variety adoption and farm production efficiency: Accounting for unobservable selection bias and technology gaps among smallholder farmers in Ghana. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, G.K.; Bijman, J.; Pascucci, S.; Omta, O. Adoption of improved potato varieties in Ethiopia: The role of agricultural knowledge and innovation system and smallholder farmers’ quality assessment. Agric. Syst. 2013, 122, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimi, N.A.; Nikolov, P.V.; Malek, M.A.; Kumbhakar, S. The effects of access to credit on productivity: Separating technological changes from changes in technical efficiency. J. Product. Anal. 2019, 52, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obisesan, A.A.; Amos, T.T.; Akinlade, R.J. Causal effect of credit and technology adoption on farm output and income: The case of cassava farmers in Southwest Nigeria. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference of the African Association of Agricultural Economists, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 23–26 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mugumaarhahama, Y.; Mondo, J.M.; Cokola, M.C.; Ndjadi, S.S.; Mutwedu, V.B.; Kazamwali, L.M.; Cirezi, N.C.; Chuma, G.B.; Ndeko, A.B.; Ayagirwe, R.B.B. Socio-economic drivers of improved sweet potato varieties adoption among smallholder farmers in South-Kivu Province, DR Congo. Sci. Afr. 2021, 12, e00818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, N.I.; Karamalla Gaiballa, A.; Ksch, C.; Sulieman, M.; Mariod, A. Using MODIS-Derived NDVI and SAVI to distinguish Between different rangeland sites according to soil types in semi-arid areas of Sudan (North Kordofan State). Int. J. Life Sci. Eng. 2015, 1, 150–164. [Google Scholar]

- Zeinelabdein, K.A.E.; El-Nadi, A.H.H.; Babiker, I.S. Prospecting for gold mineralization with the use of remote sensing and GIS technology in North Kordofan State, central Sudan. Sci. Afr. 2020, 10, e00627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A. Gezira Scheme irrigation system performance after 80 years of operation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Water, Environment, Energy and Society, New Delhi, India, 12–16 January 2009; pp. 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Elshaikh, A.E.; Yang, S.-h.; Jiao, X.; Elbashier, M.M. Impacts of Legal and Institutional Changes on Irrigation Management Performance: A Case of the Gezira Irrigation Scheme, Sudan. Water 2018, 10, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, J.H.; Nelson, F.D. Linear Probability, Logit, and Probit Models; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gujarathi, D.M. Gujarati: Basic Econometrics; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chandio, A.A.; Jiang, Y.; Rehman, A.; Akram, W. Does formal credit enhance sugarcane productivity? A farm-level Study of Sindh, Pakistan. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 2158244020988533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, S.E.; Ahmad, M.M.; Panezai, S. Landholding size and farmers’ access to credit and its utilisation in Pakistan. Dev. Pract. 2016, 26, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aregay, F.A.; Minjuan, Z. Impact of irrigation on fertilizer use decision of farmers in China: A case study in Weihe River Basin. J. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 5, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, B.K.; Abrha, B.K.; Weldegiorgis, K.A. Adoption and impact of agricultural technologies on farm income: Evidence from Southern Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Int. J. Food Agric. Econ. 2014, 2, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, G.; Debebe, S. Factors affecting use of organic fertilizer among smallholder farmers in Sekela district of Amhara region, Northwestern Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1669398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).