How Tourist Experience Quality, Perceived Price Reasonableness and Regenerative Tourism Involvement Influence Tourist Satisfaction: A Study of Ha’il Region, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Examine the impact of tourist experience quality (escapism, relaxation, enjoyment, involvement), perceived price reasonableness, and regenerative tourism involvement on the tourist satisfaction;

- Explore the moderating effect of tourist destination loyalty and destination image on the relationships quality of tourist experience (escapism, relaxation, enjoyment, involvement), perceived price reasonableness, and regenerative tourism involvement have with tourist satisfaction.

Theoretical Framework

2. Literature Review

2.1. Landscape Perception and Tourist Experience through the Lens of an Experiential Approach

2.2. Influence of Tourist Experience Quality on Tourist Satisfaction

2.3. Influence of Perceived Price Reasonableness on Tourist Satisfaction

2.4. Influence of Regenerative Tourism Involvement on Tourist Satisfaction

2.5. The Moderating Role of Destination Image in the Relationship between Tourist Experience Quality, Perceived Price Reasonableness, Regenerative Tourism Involvement, and Tourist Satisfaction

2.6. The Moderating Role of Destination Image in the Relationship between Tourist Experience Quality, Perceived Price Reasonableness, Regenerative Tourism Involvement and Tourist Satisfaction

3. Methods

3.1. Measurement Development

3.2. Data Collection Method

4. Results

4.1. Sample Profile

4.2. Model Evaluations

4.3. Measurement Model

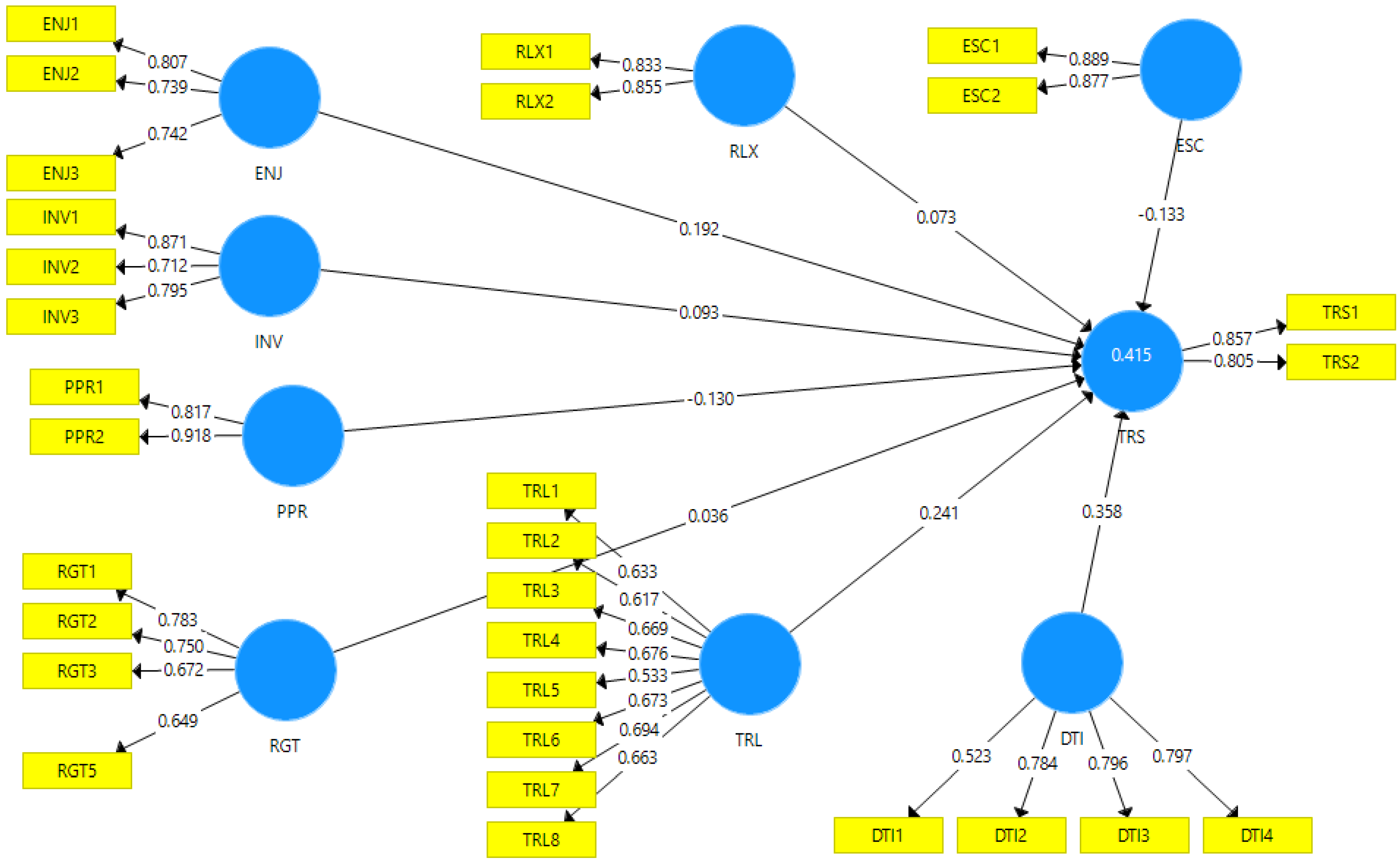

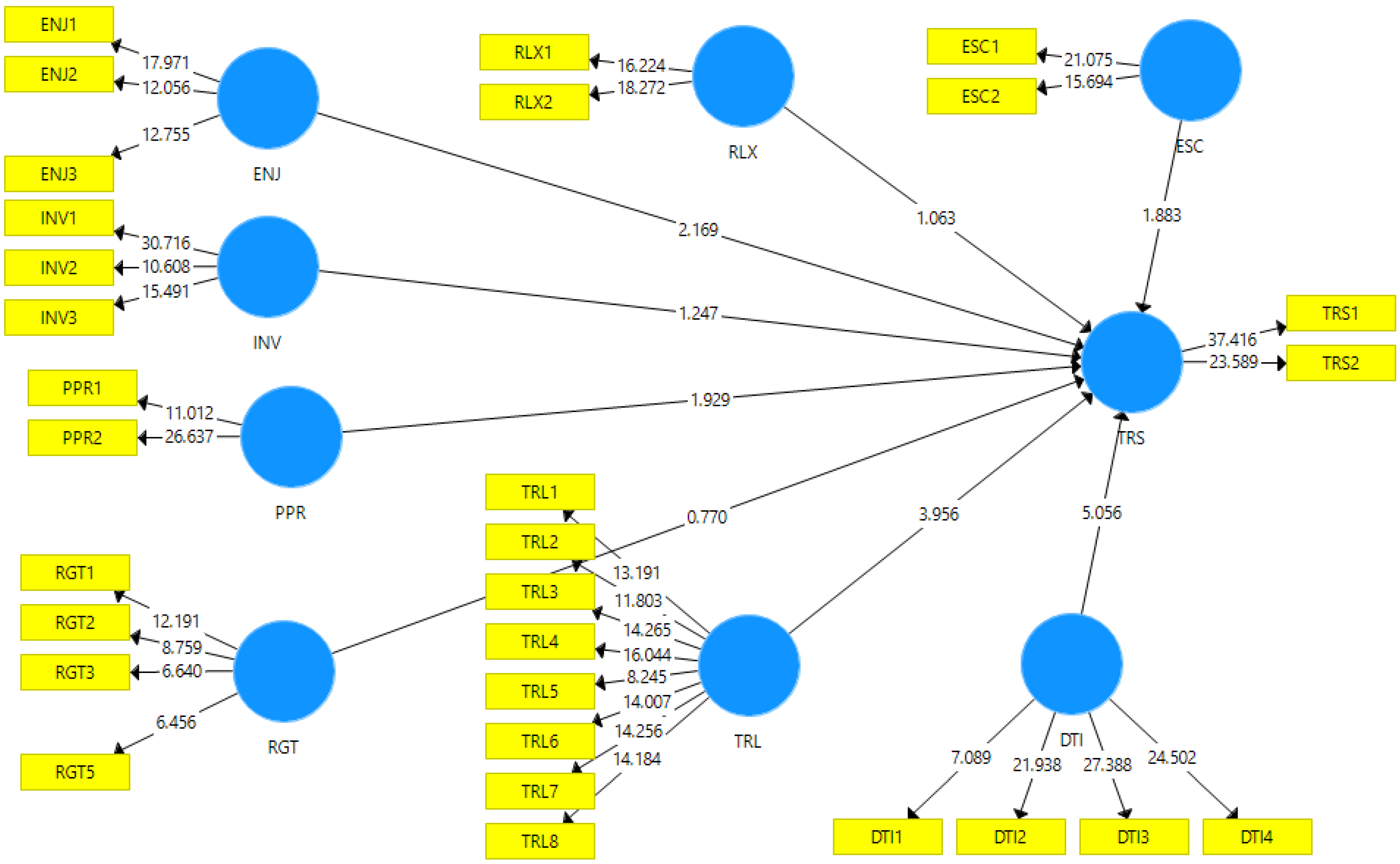

4.4. Structural Model

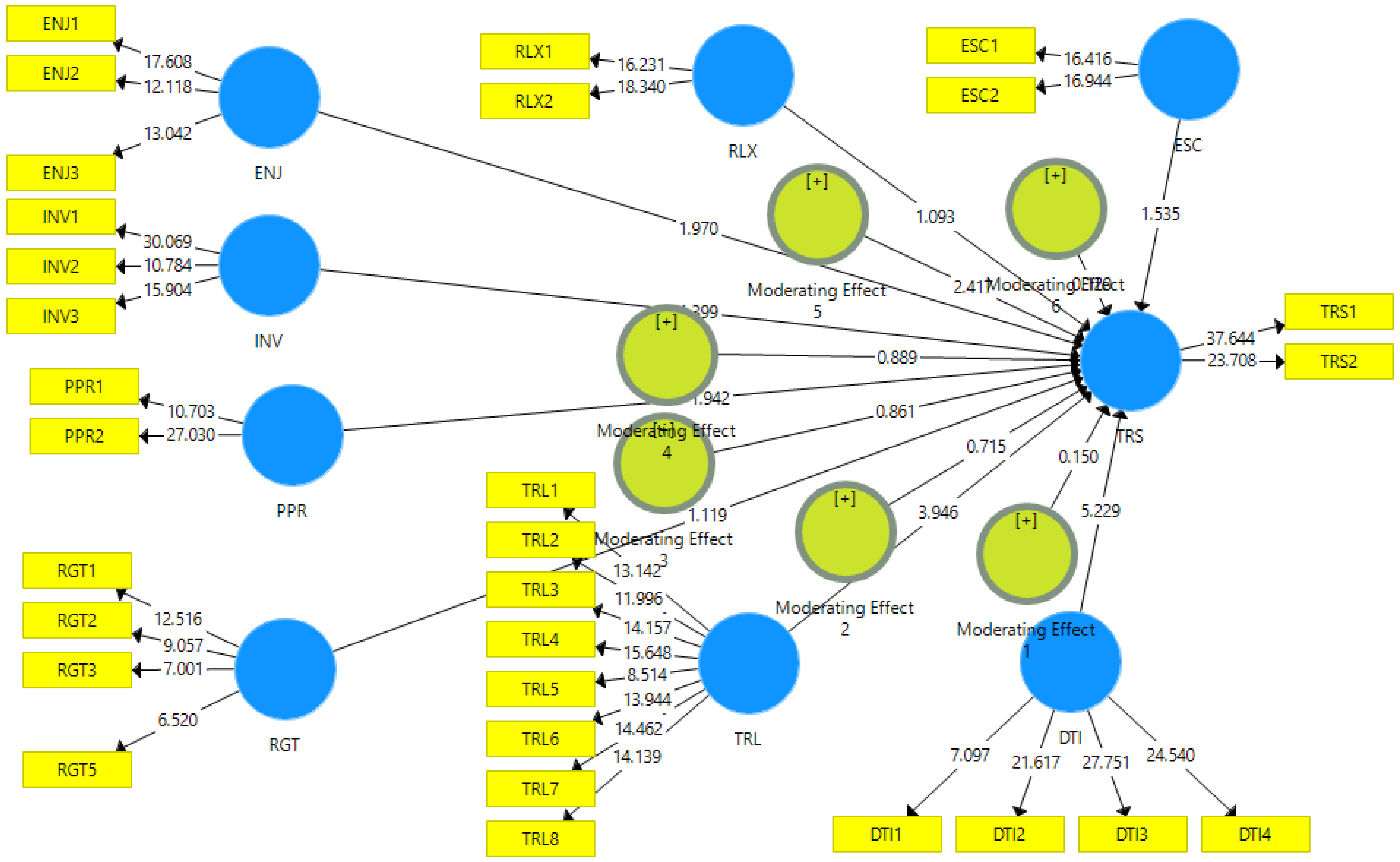

4.5. The Moderating Effects

4.5.1. Moderating Effect of Destination Image

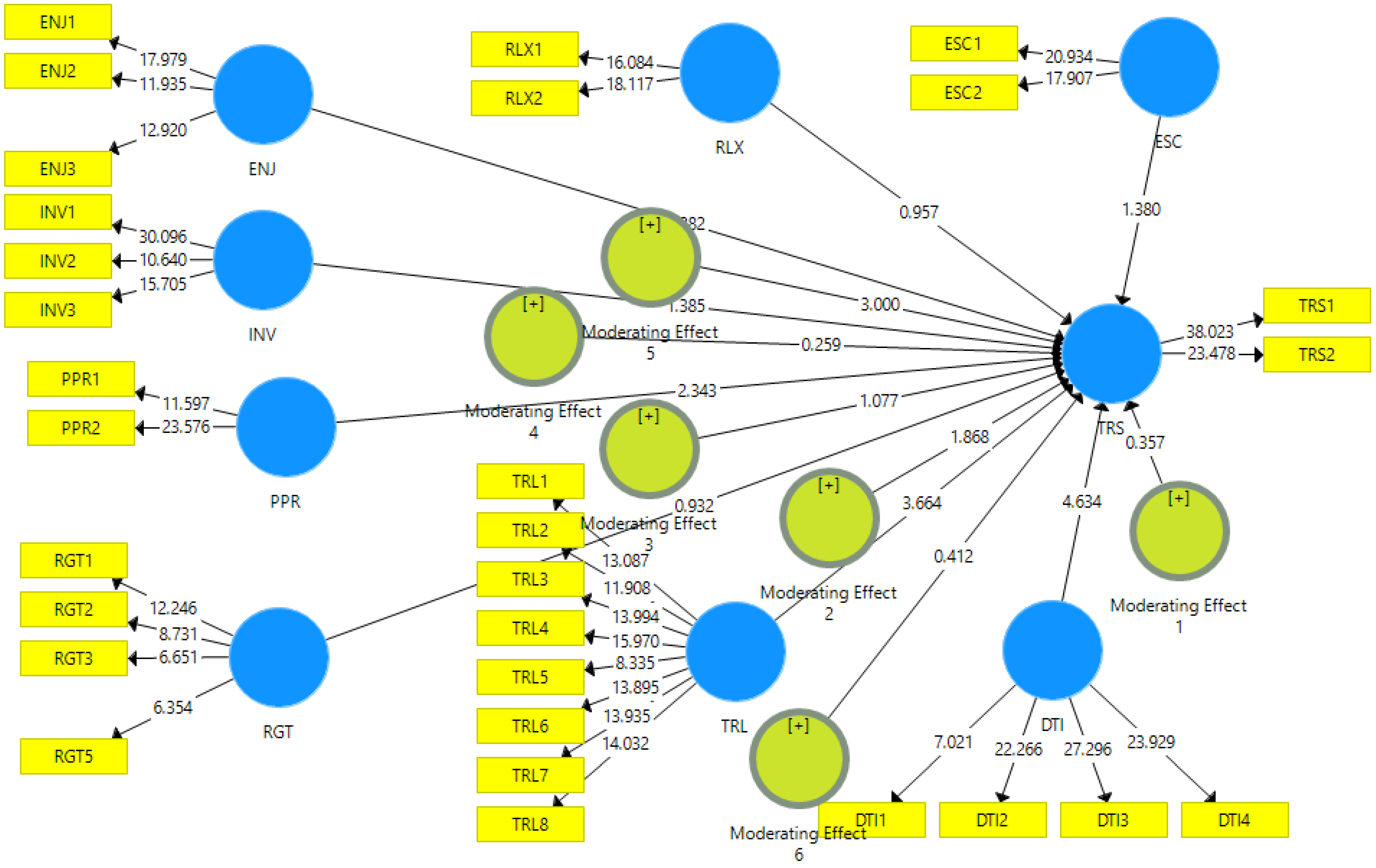

4.5.2. Moderating Effect of Tourist Destination Loyalty

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Question | |

|---|---|---|

| During My Visit to Ha’il Region, I Felt | ||

| that I had escaped from everyday life | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) |

| that I could forget everyday problems. | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| physically comfortable | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) |

| relaxed | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| that I was doing something I really liked to do | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) |

| that I was doing something memorable | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| that I was having fun | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| that I was involved in the process | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) |

| that there was an element of choice in the process. | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| that I had some control over the outcome | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| I think the prices at Ha’il destination are reasonable. | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) |

| The price for the tour at Ha’il region is appropriate. | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| Overall, the price charged at Ha’il region is inexpensive. | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| I take care of natural, social, and cultural environment of places I visit | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) |

| I respect monuments of the places I visit | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| I try to learn about culture and tradition of places I visit | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| I buy products crafted by local people from places I visit | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| I get engaged in host culture and tradition of places I visit | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| My overall evaluation of Ha’il region is positive. | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) |

| My overall assessment of this tour experience is favorable. | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| I am satisfied with this tourism experience | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| I will say positive things about this destination. | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) |

| I will tell other people about this place. | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| I will speak about the good experiences on this trip to other people. | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| I intend to revisit this destination in the future. | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| It is very likely that I will come back to this place in the future. | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| I am willing to return to this destination in the future. | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| It is acceptable to pay for traveling to this destination. | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| I am willing to spend at this place (e.g., shopping, attending recreational activities/events). | Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree (7 point Likert) | |

| According to your experience on Ha’il region, how would you describe the image of Ha’il region? | Very Bad–Very Good (7 point Likert) |

| According to your experience on Ha’il region, how would you describe the image of Ha’il region? | Very Negative–Very Positive (7 point Likert) | |

| According to your experience on Ha’il region, how would you describe the image of Ha’il region? | Very unfavorable–Very favorable (7 point Likert) | |

| According to your experience on Ha’il region, how would you describe the image of Ha’il region? | Don’t like at all–Like very much (7 point Likert) |

References

- Saudi Vision 2030. Vision Realization Programs. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/vrps/ (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- WTTC. World Travel and Tourism Council, Global Economic Impact and Trends. 2019. Available online: https://www.wttc.org/economic-impact/country-analysis/ (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Visit Saudi Home Page. Available online: https://www.visitsaudi.com/en/see-do/destinations/hail (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Welcome Saudi Home Page. Available online: https://welcomesaudi.com/destination/hail (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Dredge, D. Regenerative tourism: Transforming mindsets, systems and practices. J. Tour. Futures 2022, 8, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, A. Flourishing beyond sustainability. In ETC Workshop in Krakow; ETC Corporate: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F.; Amin, M.; Cobanoglu, C. An integrated model of service experience, emotions, satisfaction, and price acceptance: An empirical analysis in the Chinese hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 449–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.; Jang, S.S. To compare or not to compare? Comparative appeals in destination advertising of ski resorts. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 10, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.L.; Lee, S.; Goh, B.; Han, H. Impacts of cruise service quality and price on vacationers’ cruise experience: Moderating role of price sensitivity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, G.; Lee, J.; Park, J.; Chang, T.W. Developing performance measurement system for Internet of Things and smart factory environment. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 2590–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Jin, N.; Sangmook, L.; Hyuckgi, L. The effect of experience quality on perceived value, satisfaction, image and behavioral intention of water park patrons: New versus repeat visitors. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.O.; Hwang, J. Saving golf courses from business troubles. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S. A path analytic model of visitation intention involving information sources, socio-psychological motivations, and destination image. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2000, 8, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A. Green values and buying behaviour of consumers in Saudi Arabia: An empirical study. Int. J. Green Econ. 2017, 11, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossberg, L. A marketing approach to the tourist experience. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2007, 7, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.J.; Scott, N.; Lee, T.J.; Ballantyne, R. Benefits of visiting a ‘dark tourism’ site: The case of the Jeju April 3rd Peace Park, Korea. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, F.S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.B.; Chan, A. A conceptual framework of hotel experience and customer-based brand equity: Some research questions and implications. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 22, 174–193. [Google Scholar]

- Cetin, G.; Anil, B. Components of cultural tourists’ experiences in destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyarra, M.C.; Cote, I.M.; Gill, J.A.; Tinch, R.R.; Viner, D.; Watkinson, A.R. Island-specific preferences of tourists for environmental features: Implications of climate change for tourism-dependent states. Environ. Conserv. 2005, 32, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Marie, H. Regenerative tourism model: Challenges of adapting concepts from natural science to tourism industry. J. Sustain. Resil. 2022, 2, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.K.; Lee, C.K.; Choi, J.; Yoon, S.M.; Hart, R.J. Tourism’s role in urban regeneration: Examining the impact of environmental cues on emotion, satisfaction, loyalty, and support for Seoul’s revitalized Cheonggyecheon stream district. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 726–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craggs, R. Tourism and Urban Regeneration: An Analysis of Visitor Perception, Behaviour and Experience at the Quays in Salford. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Salford, Salford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, A. A future of tourism industry: Conscious travel, destination recovery and regenerative tourism. J. Sustain. Resil. 2021, 1, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Esu, B.B.; Arrey, V.M.E. Tourists’ satisfaction with cultural tourism festival: A case study of Calabar Carnival Festival, Nigeria. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 4, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Pierskalla, C. Impact of past experience on perceived value, overall satisfaction, and destination loyalty: A comparison between visitor and resident attendees of a festival. Event Manag. 2011, 15, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, M. Tourism destination loyalty. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Tsai, D. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, J.E.; Sanchez, M.I.; Sanchez, J. Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationship. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.A.; Wu, B.T.; Bai, B. Destination image and loyalty. Tour. Rev. Int. 2003, 7, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.; Gartner, W.C. Destination image and its functional relationships. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Adam, B.; Chris, C. China’s tourism in a global financial crisis: A computable general equilibrium approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; González, F.J.M. The importance of quality, satisfaction, trust, and image in relation to rural tourist loyalty. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 25, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Kim, L.H.; Im, H.H. A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S. A study of event quality, destination image, perceived value, tourist satisfaction, and destination loyalty among sport tourists. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 940–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, M.M.; Araña, J.E.; León, C.J.; Moreno-Gil, S. Economic valuation of tourism destination image. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 741–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Martin, J.D. Tourists’ characteristics and the perceived image of tourist destinations: A quantitative analysis. A case study of Lanzarote, Spain. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Han, H. Tourist experience quality and loyalty to an island destination: The moderating impact of destination image. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgazzar, F. Arab News. Saudi Arabia Thinking about the World with Sustainable Tourism Moves: Ex-Mexico President. 11 November 2022. Available online: https://www.arabnews.com/node/2197931/business-economy (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Zawya. Saudi: Red Sea Global Announces First Partners for Sustainable Mobility. 15 November 2022. Available online: https://www.zawya.com/en/business/transport-and-logistics/saudi-red-sea-global-announces-first-partners-for-sustainable-mobility-h7680evd (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Paraskevopoulos, S.; Papadopoulos, I. Exploring Students’ Perceptions about Landscapes. Int. J. Learn. 2009, 16, 561–576. [Google Scholar]

- Zube, E.H.; Sell, J.L.; Taylor, J.G. Landscape perception: Research, application and theory. Landsc. Plan. 1982, 9, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zube, E.H.; Robert, O.B.; Julius, G.F. Landscape Assessment: Values, Perceptions, and Resources; Dowden, Hutchinson, & Ross: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ittelson, W.H. Environment and Cognition; Seminar Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Swarbrooke, J.; Horner, S. Consumer Behaviour in Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Del Bosque, I.R.; San Martın, H. Tourist satisfaction: A cognitive-affective model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridgen, J.D. Environmental psychology and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1984, 11, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, M.J. The value belief emotion norm model: Investigating customers’ eco-friendly behavior. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, A. Environmental aesthetics. In The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 561–576. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.C.; Li, T. A study of experiential quality, perceived value, heritage image, experiential satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 904–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Li, M.Y.; Li, T. A study of experiential quality, experiential value, experiential satisfaction, theme park image, and revisit intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 26–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Shaw, G.; Coles, T.; Prillwitz, J. A holiday is a holiday’: Practicing sustainability, home and away. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C.W.; Chen, M.C. A study of experience expectations of museum visitors. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cova, B.; Carù, A.; Cayla, J. Re-conceptualizing escape in consumer research. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2018, 21, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsignon, F.; Lunardo, R.; Michrafy, M. Why are international visitors more satisfied with the tourism experience? The role of hedonic value, escapism, and psychic distance. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 1771–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, A.; Schneider, F.M. Entertainment and politics revisited: How non-escapist forms of entertainment can stimulate political interest and information seeking. J. Commun. 2014, 64, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Alnuzhah, A.S. Identifying travel motivations of Saudi domestic tourists: Case of Hail province in Saudi Arabia. GeoJ. Tour. Geosites 2022, 43, 1118–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canniford, R.; Shankar, A. Purifying practices: How consumers assemble romantic experiences of nature. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 39, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.C.; Wang, M.Y.; Lee, C.F.; Chen, Y.C. Assessing travel motivations of cultural tourists: A factor-cluster segmentation analysis. J. Inf. Optim. Sci. 2015, 36, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEYİTOGLU, F. Cappadocia: The effects of tourist motivation on satisfaction and destination loyalty. J. Tour. 2020, 6, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaludin, M.; Johari, S.; Aziz, A.; Kayat, K.; Yusof, A. Examining structural relationship between destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty. Int. J. Indep. Res. Stud. 2012, 1, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie, D.; Chang, J.C. Tourist satisfaction: A view from a mixed international guided package tour. J. Vacat. Mark. 2005, 11, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Duncan, J.; Chung, B.W. Involvement, satisfaction, perceived value, and revisit intention: A case study of a food festival. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2015, 13, 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A. An empirical study of perception of consumers towards online shopping in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Retail. Rural Bus. Perspect. 2016, 5, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Prebensen, N.K.; Woo, E.; Chen, J.S.; Uysal, M. Motivation and involvement as antecedents of the perceived value of the destination experience. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Beeler, C. An investigation of predictors of satisfaction and future intention: Links to motivation, involvement, and service quality in a local festival. Event Manag. 2009, 13, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josiam, B.M.; Kinley, T.R.; Kim, Y.K. Involvement and the tourist shopper: Using the involvement construct to segment the American tourist shopper at the mall. J. Vacat. Mark. 2005, 11, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Al Shammari, S.; Al-Mamary, Y.H. Role of religiosity and the mediating effect of luxury value perception in luxury purchase intention: A cross-cultural examination. J. Islam. Mark. 2021, 13, 975–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapsari, R.; Clemes, M.; Dean, D. The mediating role of perceived value on the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction: Evidence from Indonesian airline passengers. Procedia Econ. Fin. 2016, 35, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A. Consumers’ perceived value of luxury goods through the lens of Hofstede cultural dimensions: A cross-cultural study. J. Pub. Aff. 2021, 22, e2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, B. Shifting mental models from ‘sustainability’ to regeneration. Build. Res. Inf. 2007, 35, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegan, R. In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, M. Regenerative Tourism Invites Travelers to Get Their Hands Dirty. Smithsonian Magazine, 21 June 2022. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/regenerative-tourism-invites-travelers-to-get-their-hands-dirty-180980215/ (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Chen, J.; Pellegrini, P.; Xu, Y.; Ma, G.; Wang, H.; An, Y.; Shi, Y.; Feng, X. Evaluating residents’ satisfaction before and after regeneration. The case of a high-density resettlement neighbourhood in Suzhou, China. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2144137. [Google Scholar]

- Razović, M. Sustainable development and level of satisfaction of tourists with elements of tourist offer of destination. Tour. South. East. Eur. 2013, 371–385. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2289885 (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Kim, M.J.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, C.K.; Chung, J.Y. The role of perceived ethics in the decision-making process for responsible tourism using an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 31, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afacan, Y. Resident satisfaction for sustainable urban regeneration. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Munic. Eng. 2015, 168, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layson, J.P.; Nankai, X. Public participation and satisfaction in urban regeneration projects in Tanzania: The case of Kariakoo, Dar es Salaam. Urban Plan. Transp. Res. 2015, 3, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.T.H.; Lee, W.I.; Chen, T.H. Environmentally responsible behavior in ecotourism: Exploring the role of destination image and value perception. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 876–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Ryan, C. Destination positioning analysis through a comparison of cognitive, affective, and conative perceptions. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Richardson, S.L. Motion picture impacts on destination images. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete Alcocer, N.; López Ruiz, V.R. The role of destination image in tourist satisfaction: The case of a heritage site. Econ. C Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2020, 33, 2444–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, G. The Effects of Destination Image on Tourist Satisfaction: The Case of Don-Wai Floating Market in Nakhon Pathom, Thailand. Acad. Tur. Tour. Innov. J. 2021, 13, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, M.M.; Tabaeeian, R.A.; Tavakoli, H. The effect of destination image on tourist satisfaction, intention to revisit and WOM: An empirical research in Foursquare social media. In Proceedings of the 2016 10th International Conference on e-Commerce in Developing Countries: With Focus on e-Tourism (ECDC), Isfahan, Iran, 15–16 April 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, F.; Tepanon, Y.; Uysal, M. Measuring tourist satisfaction by attribute and motivation: The case of a nature-based resort. J. Vacat. Mark. 2008, 4, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chi, C.G.Q.; Xu, H. Developing destination loyalty: The case of Hainan Island. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 547–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L. The effects of environmental and luxury beliefs on intention to patronize green hotels: The moderating effect of destination image. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 904–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokosalakis, C.; Bagnall, G.; Selby, M.; Burns, S. Place image and urban regeneration in Liverpool. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2006, 30, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U. Barriers Affecting the Diffusion of Business-to-Consumer Online Retailing Acceptance in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2019, 12, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Gursoy, D. An investigation of tourists’ destination loyalty and preferences. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 13, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Woosnam, K.M.; Pinto, P.; Silva, J.A. Tourists’ destination loyalty through emotional solidarity with residents: An integrative moderated mediation model. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Chen, X. The effects of perceived service quality on repurchase intentions and subjective well-being of Chinese tourists: The mediating role of relationship quality. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Oh, Y.; Hong, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, W.H. The Moderating Roles of Destination Regeneration and Place Attachment in How Destination Image Affects Revisit Intention: A Case Study of Incheon Metropolitan City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidary, A. How Is Destination Loyalty Correlated With Sport Tourism Propagation? An Overview. Marathon Dep. Pshisycal Educ. Sport Acad. Econ. Stud. Buchar. Rom. 2014, 6, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Kim, W. Outcomes of relational benefits: Restaurant customers’ perspective. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2009, 26, 820–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxham, J.G.; Netemeyer, R.G. Modeling customer perceptions of complaint handling over time: The effects of perceived justice on satisfaction and intent. J. Retail. 2002, 78, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Molina, M.A.; Frías-Jamilena, D.M.; Castañeda García, J.A. The contribution of website design to the generation of tourist destination image: The moderating effect of involvement. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.D.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. The effect of tourism services on travelers’ quality of life. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Gazette. Hail Governor Opens 3rd Edition of Saudi Dakar Rally 2022. 2 January 2022. Available online: https://saudigazette.com.sa/article/615390 (accessed on 24 September 2022).

- Van de Vijver, F.J.; Tanzer, N.K. Bias and equivalence in cross-cultural assessment: An overview. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 47, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, D.R.; Farr, H.; Slee, R.W. Estimating and interpreting the local economic benefits of visitor spending: An explanation. Leis. Stud. 2000, 19, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfiluk, E. Innovativeness of tourism enterprises: Example of Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALSAID, K.N.; Nour El Houda, B.E.N. Experiential Marketing Impact on Experiential Value and Customer Satisfaction- Case of Winter Wonderland Amusement Park in Saudi Arabia. Expert J. Mark. 2020, 8, 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ajoon, E.; Rao, Y. A study on consciousness of young travelers towards regenerative tourism: With reference to Puducherry. J. Tour. Econ. Appl. Res. 2020, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sari, N.M.; Nugroho, I.; Julitasari, E.N.; Hanafie, R. The Resilience of Rural Tourism and Adjustment Measures for Surviving The COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Bromo Tengger Semeru National Park, Indonesia. For. Soc. 2022, 6, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. Al Arabiya English. Saudi Arabia Tops Arab Countries for Most Tourists in 2022: WTO. 5 October 2022. Available online: https://english.alarabiya.net/News/gulf/2022/10/05/Saudi-Arabia-tops-Arab-countries-for-most-tourists-in-2022-WTO (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Vinzi, V.E.; Trinchera, L.; Amato, S. PLS path modeling: From foundations to recent developments and open issues for model assessment and improvement. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 47–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares: The better approach to structural equation modeling? Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M. Smart PLS 2.0 (M3). 2005. Available online: https://www.smartpls.de (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ortinau, D.J.; Harrison, D.E. Essentials of Marketing Research; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 4th ed.; 11.0 update; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, R.; Karahanna, E. Time flies when you’re having fun: Cognitive absorption and beliefs about information technology usage. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 665–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Shi, N.; Cheung, C.M.; Lim, K.H.; Sia, C.L. Consumer’s decision to shop online: The moderating role of positive informational social influence. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiomy, A.E.; Jones, E.; Goode, M.M. The influence of menu design, menu item descriptions and menu variety on customer satisfaction. A case study of Egypt. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, S.; Alvarez, M.D. Can tourism promotions influence a country’s negative image? An experimental study on Israel’s image. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslop, L.A.; Nadeau, J.; O’reilly, N.; Armenakyan, A. Mega-event and country co-branding: Image shifts, transfers and reputational impacts. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2013, 16, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreshoodi, S.A.; Rehman, A.U.; Alshammari, S.A.; Khan, T.N.; Moid, S. Women Entrepreneurs in Saudi Arabia: A Portrait of Progress in the Context of Their Drivers and Inhibitors. J. Enterprising Cult. 2022, 30, 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variables | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 78.60% |

| Female | 21.40% | |

| Age (years) | Below 20 | 1.80% |

| 20–29 | 52.40% | |

| 30–39 | 31.80% | |

| 40–49 | 11% | |

| 50–59 | 2% | |

| Over 60 | 1% | |

| Education | High school or lower | 3% |

| Diploma | 7% | |

| Undergraduate | 6.50% | |

| Graduate | 52.80% | |

| Postgraduate or higher | 30.70% | |

| Occupation | Businessmen | 32.60% |

| Professional | 23.70% | |

| Private sector employee | 18.60% | |

| Self-employed | 16.60% | |

| Government employees | 8.50% | |

| Monthly Income (US$) | Less than 2500 | 4% |

| 2501–4000 | 7% | |

| 4001–5500 | 61% | |

| 5501–7000 | 23% | |

| 7001 and higher | 5% | |

| Tourist’s Home Country | United Arab Emirates | 28% |

| Egypt | 21% | |

| Qatar | 12.50% | |

| Morocco | 11% | |

| United Kingdom | 9% | |

| Malaysia | 7% | |

| Others | 11.50% | |

| Outer Loading | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTI | ENJ | ESC | INV | PPR | RGT | RLX | TRL | TRS | |

| DTI1 | 0.523 | ||||||||

| DTI2 | 0.784 | ||||||||

| DTI3 | 0.796 | ||||||||

| DTI4 | 0.797 | ||||||||

| ENJ1 | 0.807 | ||||||||

| ENJ2 | 0.739 | ||||||||

| ENJ3 | 0.742 | ||||||||

| ESC1 | 0.889 | ||||||||

| ESC2 | 0.877 | ||||||||

| INV1 | 0.871 | ||||||||

| INV2 | 0.712 | ||||||||

| INV3 | 0.795 | ||||||||

| PPR1 | 0.817 | ||||||||

| PPR2 | 0.918 | ||||||||

| RGT1 | 0.783 | ||||||||

| RGT2 | 0.750 | ||||||||

| RGT3 | 0.672 | ||||||||

| RGT5 | 0.649 | ||||||||

| RLX1 | 0.833 | ||||||||

| RLX2 | 0.855 | ||||||||

| TRL1 | 0.633 | ||||||||

| TRL2 | 0.617 | ||||||||

| TRL3 | 0.669 | ||||||||

| TRL4 | 0.676 | ||||||||

| TRL5 | 0.533 | ||||||||

| TRL6 | 0.673 | ||||||||

| TRL7 | 0.694 | ||||||||

| TRL8 | 0.663 | ||||||||

| TRS1 | 0.857 | ||||||||

| TRS2 | 0.805 | ||||||||

| Construct Reliability and Validity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

| DTI | 0.703 | 0.820 | 0.539 |

| ENJ | 0.649 | 0.807 | 0.583 |

| ESC | 0.718 | 0.876 | 0.780 |

| INV | 0.714 | 0.837 | 0.632 |

| PPR | 0.686 | 0.860 | 0.755 |

| RGT | 0.697 | 0.807 | 0.512 |

| RLX | 0.597 | 0.832 | 0.713 |

| TRL | 0.800 | 0.851 | 0.418 |

| TRS | 0.555 | 0.817 | 0.691 |

| Discriminant Validity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fornell-Larcker Criterion | |||||||||

| DTI | ENJ | ESC | INV | PPR | RGT | RLX | TRL | TRS | |

| DTI | 0.734 | ||||||||

| ENJ | 0.442 | 0.763 | |||||||

| ESC | 0.364 | 0.579 | 0.883 | ||||||

| INV | 0.416 | 0.695 | 0.578 | 0.795 | |||||

| PPR | 0.351 | 0.766 | 0.537 | 0.639 | 0.869 | ||||

| RGT | 0.390 | 0.193 | 0.163 | 0.122 | 0.153 | 0.716 | |||

| RLX | 0.402 | 0.655 | 0.720 | 0.592 | 0.562 | 0.162 | 0.844 | ||

| TRL | 0.645 | 0.381 | 0.313 | 0.367 | 0.330 | 0.367 | 0.357 | 0.646 | |

| TRS | 0.586 | 0.385 | 0.226 | 0.351 | 0.257 | 0.283 | 0.321 | 0.534 | 0.831 |

| Serial # | Hypothesized Paths | Path Coefficients | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p-Values | Decisions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DTI → TRS | 0.358 | 0.071 | 5.056 | 0.000 * | Supportive |

| 2 | ENJ → TRS | 0.192 | 0.089 | 2.169 | 0.030 * | Supportive |

| 3 | ESC → TRS | −0.133 | 0.071 | 1.883 | 0.060 | Not supportive |

| 4 | INV → TRS | 0.093 | 0.074 | 1.247 | 0.212 | Not supportive |

| 5 | PPR → TRS | −0.130 | 0.068 | 1.929 | 0.054 | Not supportive |

| 6 | RGT → TRS | 0.036 | 0.047 | 0.770 | 0.441 | Not supportive |

| 7 | RLX → TRS | 0.073 | 0.069 | 1.063 | 0.288 | Not supportive |

| 8 | TRL → TRS | 0.241 | 0.061 | 3.956 | 0.000 * | Supportive |

| Serial # | Hypothesized Paths | Path Coefficients | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p-Values | Decisions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Moderating Effect 1 → TRS | 0.012 | 0.078 | 0.150 | 0.881 | Not supportive |

| 2 | Moderating Effect 2 → TRS | 0.043 | 0.061 | 0.715 | 0.475 | Not supportive |

| 3 | Moderating Effect 3 → TRS | 0.056 | 0.066 | 0.861 | 0.389 | Not supportive |

| 4 | Moderating Effect 4 → TRS | −0.070 | 0.079 | 0.889 | 0.374 | Not supportive |

| 5 | Moderating Effect 5 → TRS | −0.112 | 0.046 | 2.417 | 0.016 * | Supportive |

| 6 | Moderating Effect 6 → TRS | 0.008 | 0.067 | 0.120 | 0.905 | Not supportive |

| Serial # | Hypothesized Paths | Path Coefficients | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p-Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Moderating Effect 1 → TRS | 0.028 | 0.078 | 0.357 | 0.721 | Not supportive |

| 2 | Moderating Effect 2 → TRS | 0.103 | 0.055 | 1.868 | 0.062 | Not supportive |

| 3 | Moderating Effect 3 → TRS | −0.060 | 0.056 | 1.077 | 0.281 | Not supportive |

| 4 | Moderating Effect 4 → TRS | −0.019 | 0.072 | 0.259 | 0.796 | Not supportive |

| 5 | Moderating Effect 5 → TRS | −0.139 | 0.046 | 3.000 | 0.003 * | Supportive |

| 6 | Moderating Effect 6 → TRS | −0.028 | 0.067 | 0.412 | 0.681 | Not supportive |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rehman, A.U.; Abbas, M.; Abbasi, F.A.; Khan, S. How Tourist Experience Quality, Perceived Price Reasonableness and Regenerative Tourism Involvement Influence Tourist Satisfaction: A Study of Ha’il Region, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021340

Rehman AU, Abbas M, Abbasi FA, Khan S. How Tourist Experience Quality, Perceived Price Reasonableness and Regenerative Tourism Involvement Influence Tourist Satisfaction: A Study of Ha’il Region, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021340

Chicago/Turabian StyleRehman, Anis Ur, Mazhar Abbas, Faraz Ahmad Abbasi, and Shoaib Khan. 2023. "How Tourist Experience Quality, Perceived Price Reasonableness and Regenerative Tourism Involvement Influence Tourist Satisfaction: A Study of Ha’il Region, Saudi Arabia" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021340

APA StyleRehman, A. U., Abbas, M., Abbasi, F. A., & Khan, S. (2023). How Tourist Experience Quality, Perceived Price Reasonableness and Regenerative Tourism Involvement Influence Tourist Satisfaction: A Study of Ha’il Region, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 15(2), 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021340