Abstract

The Xishu Historical and Cultural Celebrity Memorial Gardens are representatives of southwestern regional gardens in China. Du Fu Thatched Cottage is one of the typical examples of these gardens, with exceptional memorial, historical, and cultural significance. However, compared to other gardens in China, few research has been conducted on their digital preservation and construction connotation. In this study, the digital model of Du Fu Thatched Cottage was obtained by terrestrial laser scanning and total station technology, and its memorial analysis and preservation were studied digitally. Using three levels of point, line, and surface analysis, we examined how to digitally deconstruct the commemorative elements of Du Fu Thatched Cottage that included the memorial theme, gardening components, and design philosophy of the garden space. The study revealed the memorial space core of the Historical and Cultural Celebrity Memorial Gardens in Xishu and proposed a strategy for building a digital preservation system. The research will help to digitally protect the Du Fu Thatched Cottage and analyze methods to memorialize other traditional gardens.

1. Introduction

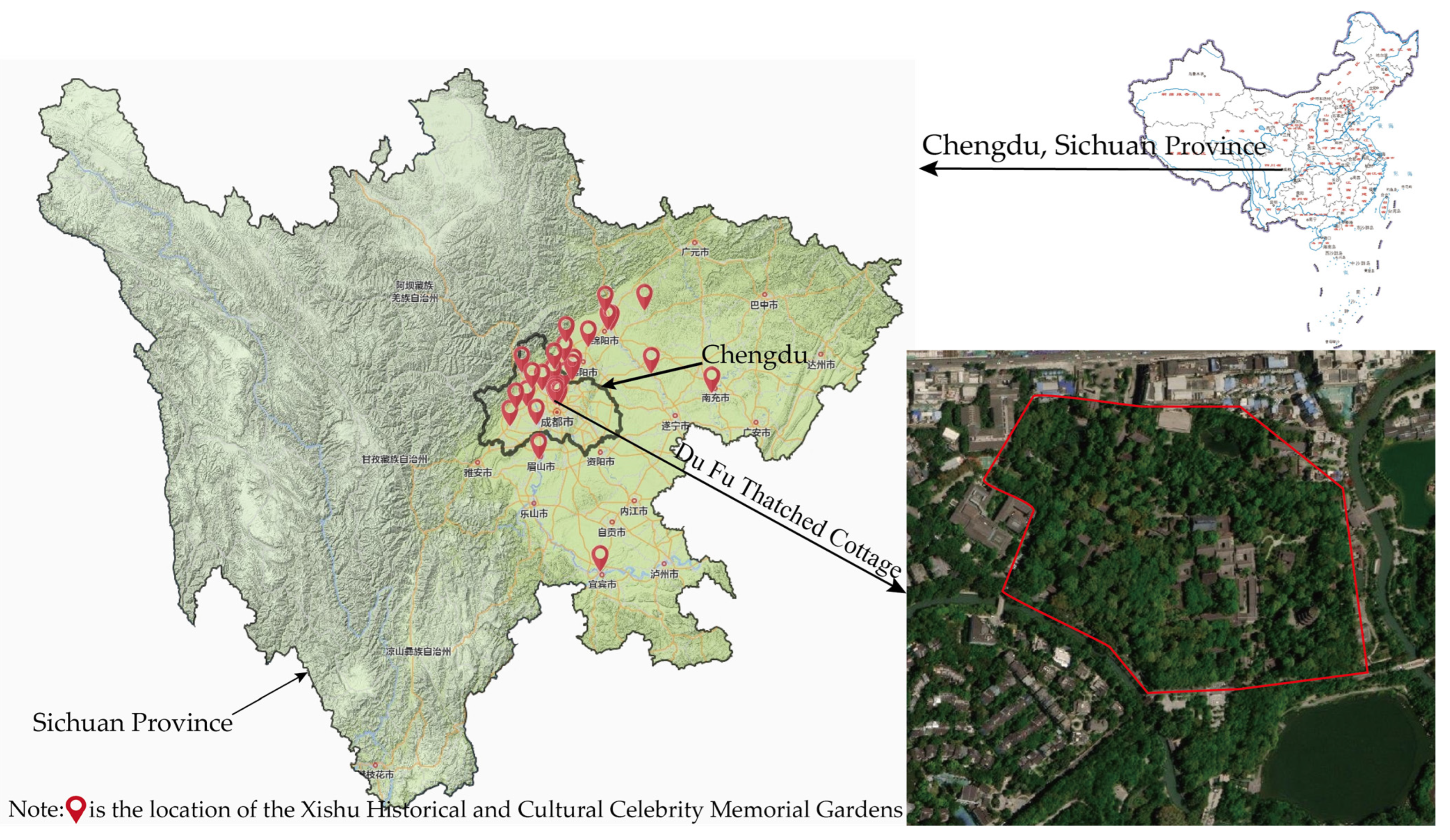

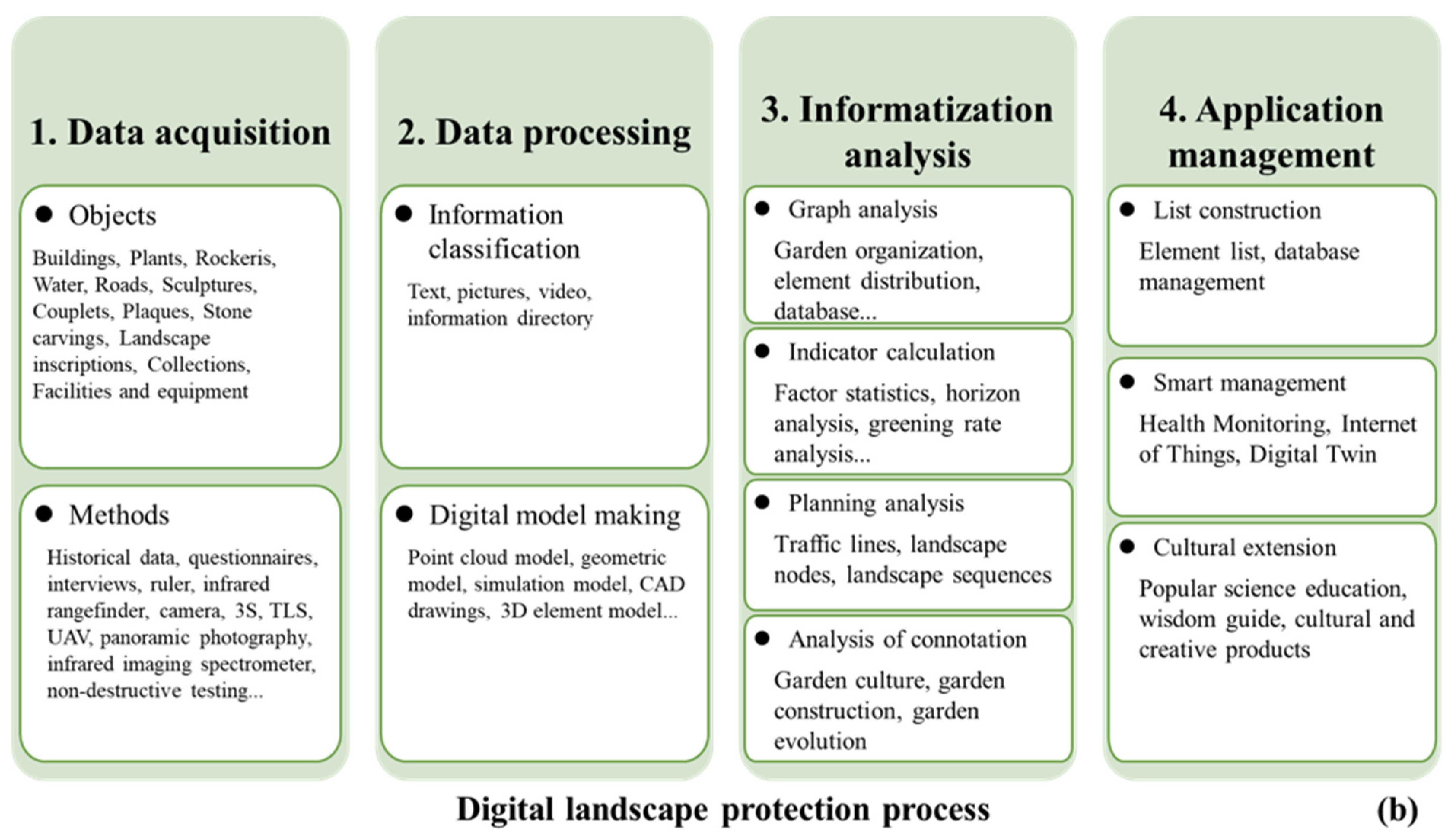

Du Fu is a global cultural celebrity [1] and a world-famous poet [2] in Chinese history. In 759 A.D., under the influence of the An Shi Rebellion, Du Fu moved in exile to Chengdu and established the Thatched Cottage, which has since evolved over the past 1200 years into the most complete and representative garden in China to commemorate Du Fu. The memorial gardens of historical and cultural celebrities in Xishu (Xishu refers to the regional space of the ancient Shu Kingdom, the Sichuan Basin, and its surrounding areas with the Chengdu Plain of Sichuan Province as the core including parts of Chongqing [3]) [4], represented by Du Fu Thatched Cottage, celebrate the regional characteristics of culture, history, and the public of Xishu. The Xishu memorial gardens are a branch in the history of classical Chinese gardens [3,4,5,6], and are rare in China because of their location in the Sichuan region (Figure 1). For example, Three-Su Shrine, Du Fu Thatched Cottage, Wuhou Shrine, Wangjiang Lou, Wenjun Jing, Li Du Ancestral Hall, and Erwang Temple were built to commemorate Su Xun, Su Shi, Su Zhe, Du Fu, Zhuge Liang, Xue Tao, Zhuo Wenjun, Li Bai, Li Bing, and other talented scholars from Sichuan. This kind of garden embodies the historical and cultural spirit encapsulated by the saying “Examine the traces of celebrities, remember the ancients and sages, and express their feelings to enlighten civilization” [3,4,6,7]. The garden conveys the feeling that “famous people, humanistic beauty, and historic sites still exist” [3,4]. It is an important heritage site for classical gardens, with important and special social, historical, and cultural values, not only in the Xishu region, but also in China. Nevertheless, the Sichuan region is located in an earthquake-prone area, where natural disasters are frequent. These classical gardens are prone to damage [8], and the lack of detailed data for garden restoration and conservation has led to the loss of historical information about the gardens and made it difficult to protect them.

Figure 1.

The distribution of the Xishu Historical and Cultural Celebrity Memorial Gardens.

In recent years, digital technologies have emerged in the conservation of cultural heritage sites including ancient locations [9] and buildings [10]. Technology now plays an important role in cultural heritage information collection [11,12], digital modeling [13], digital display, and digital monitoring [14,15,16,17]. Moreover, the application and cross integration of digital photography, terrestrial laser scanning, unmanned aerial vehicle photogrammetry, and other technologies [18,19,20,21,22] have brought new opportunities for the conservation of classical gardens by recording rich spatial elements and cultural connotations. The use of efficient, comprehensive, and detailed mapping technologies to establish visual, accurate, and comprehensive point cloud models [22], 3D models [22,23,24], solid models, and other virtual models [24,25,26] can provide important baseline data for digital archiving [19,22], quantitative analysis [27], earthquake damage simulation [26], real-time monitoring, VR scenes, digital twins, and the metaverse construction of realistic garden scenes while promoting the value of cultural heritage preservation and natural scenes for sustainable conservation, science education, and exhibitions. Taking Du Fu Thatched Cottage as an example, this study introduces digital conservation research, which is of importance as a reference value for the study of the conservation of classical gardens including historical and cultural celebrity memorial gardens in Xishu.

Recently, research on digital information collection and digital system construction has been carried out on royal and private gardens such as Qianlong Garden [28], Huanxiu Villa [29], Yuyuan Garden in Shanghai [30], and Jianxing Garden [31], but these efforts have mostly focused on digital mapping technology [16,32] and the extraction of information about the garden [15], with less attention given to the subsequent analysis and application of the data. Chinese classical gardens share commonalities in natural, irregular, comprehensive, and complex characteristics, but there are regional and cultural influences that differentiate between types of gardens. There are few reports on the digital conservation of classical gardens in southwest China, and there is a lack of a digital analytical model suitable for the Xishu region. More importantly, a digital conservation system for gardens is not yet complete.

Therefore, the study applied digital methods and technologies, focusing on the Du Fu Thatched Cottage, to provide a reference for digital conservation and scientific research on classical gardens in Xishu. The aims of this study were as follows:

Improving the methods of digital information collection for the memorial gardens of historical and cultural celebrities in Xishu.

Creation of a data processing and digital analysis model for the memorial gardens of historical and cultural celebrities in Xishu.

Creation of a digital strategy for the memorial gardens of historical and cultural celebrities in Xishu.

2. Study Location

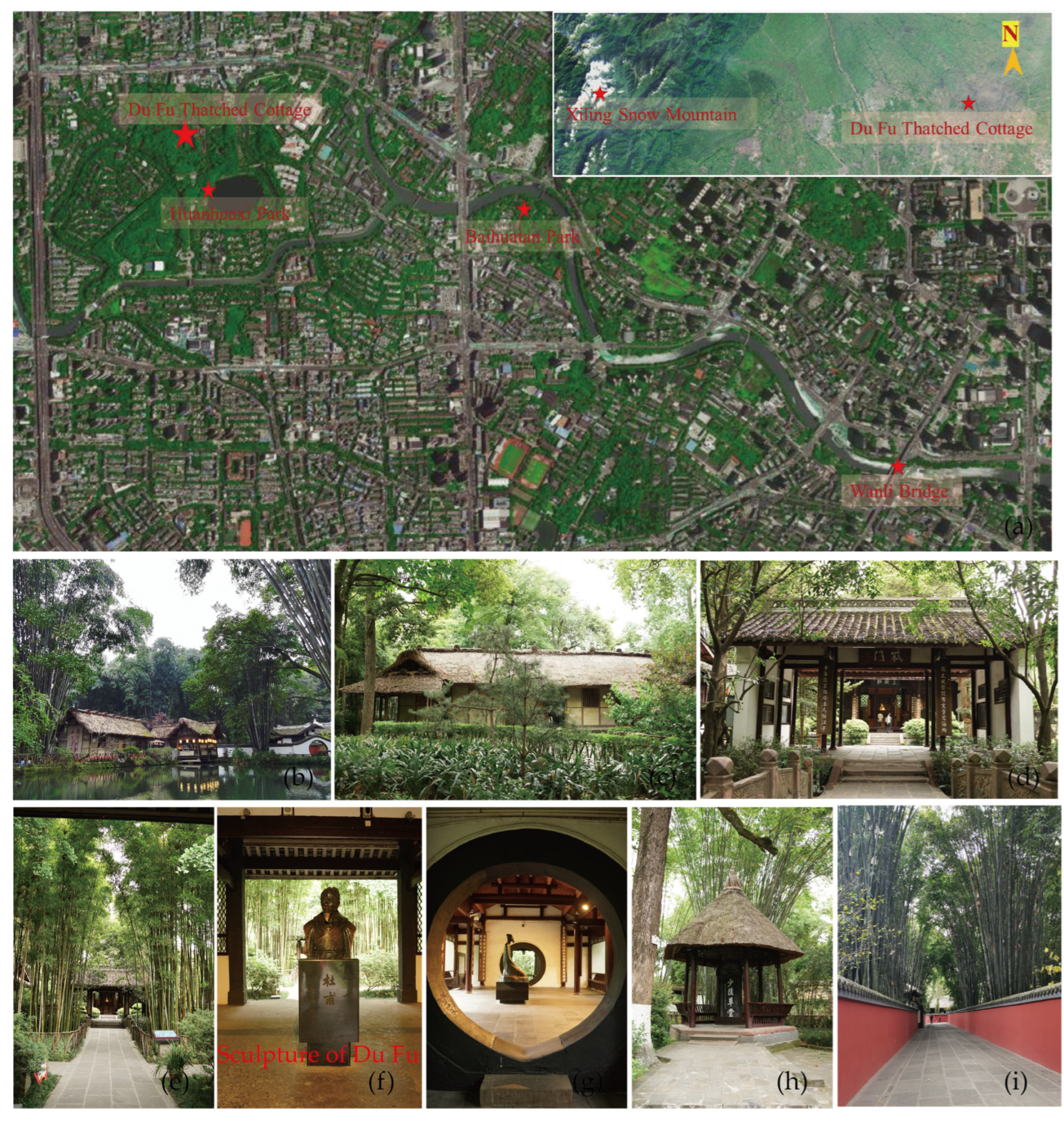

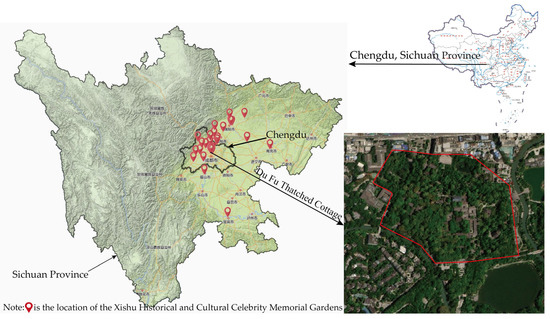

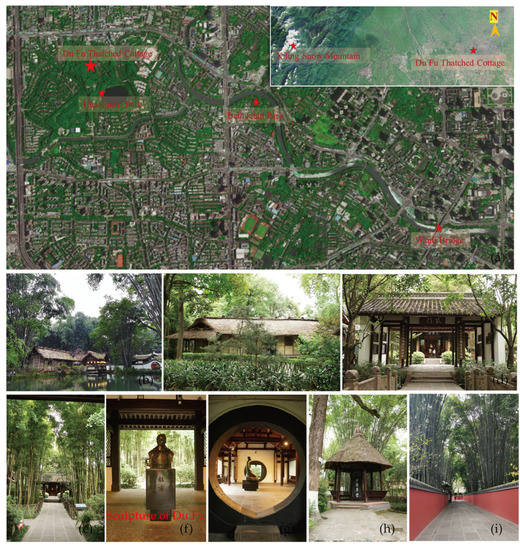

The Du Fu Thatched Cottage is located in Qingyang District, Chengdu, Sichuan Province. It covers an area of nearly 300 mu (200,000 m2) [33] (Figure 2). The site is surrounded by lush greenery and winding streams and contains a variety of elements including architecture, plants, rocks, ponds and sculptures, creating a quiet and elegant external environment. At the same time, Du Fu Thatched Cottage has a rich history, having been established on the fertile Chengdu Plain at its ‘origins’ (Du Fu’s exile in Chengdu), maintained through its ‘inheritance’ (Wei Zhuang’s ‘thinking of his people and becoming his place’), updated through ‘transformation’ (fully renovated and opened in 1952), and integrated through ‘heritage identification’ (as one site in the first batch of national key cultural relic preservation units, national first-class museums, and national 4A scenic spots) [3,4,33]. The cottage has evolved into a modern garden-style museum, enshrining the typical regional characteristics of western Sichuan Linpan with traditional memorial shrines and temple gardens and a strong cultural atmosphere of commemoration.

Figure 2.

Position and present situation of Du Fu Thatched Cottage: (a) location of Du Fu Thatched Cottage; (b) the waterscape of the southern neighbor; (c) Du Fu’s thatched cottage; (d) Chaimen; (e) Bamboo in front of the Chaimen; (f) Du Fu’s Sculpture in Shishi tang; (g) Du Fu’s Sculpture in Da Xie Hall; (h) Shaoling Thatched Cottage Tablet Pavilion; (i) The flowered path.

The spatial layout of the garden uses the pattern of “one garden, two axes, one water, one forest and one site” [3,4]. Some of the Ming and Qing Dynasty buildings and the original historical layout are still preserved in the garden, and the cultural sentiment of Du Fu poetry is conveyed through the design of the buildings, plants, ponds, couplets, and sculptures, thus creating a poetic garden. For example, its geographical location, with Xiling Snow Mountain to the west, evokes the poem by Du Fu: “ The window holds the western peaks’ snow of a thousand autumns.” [2]. To the east is the Wanli Bridge (now the Old South Gate Bridge in Chengdu), reminding the visitor of Du Fu’s description of the cottage as “A cottage south of the Thousand League Bridge, an estate north of Hundred Flowers Pool.” [2].

3. Methods

3.1. Information Acquisition Equipment and Methods

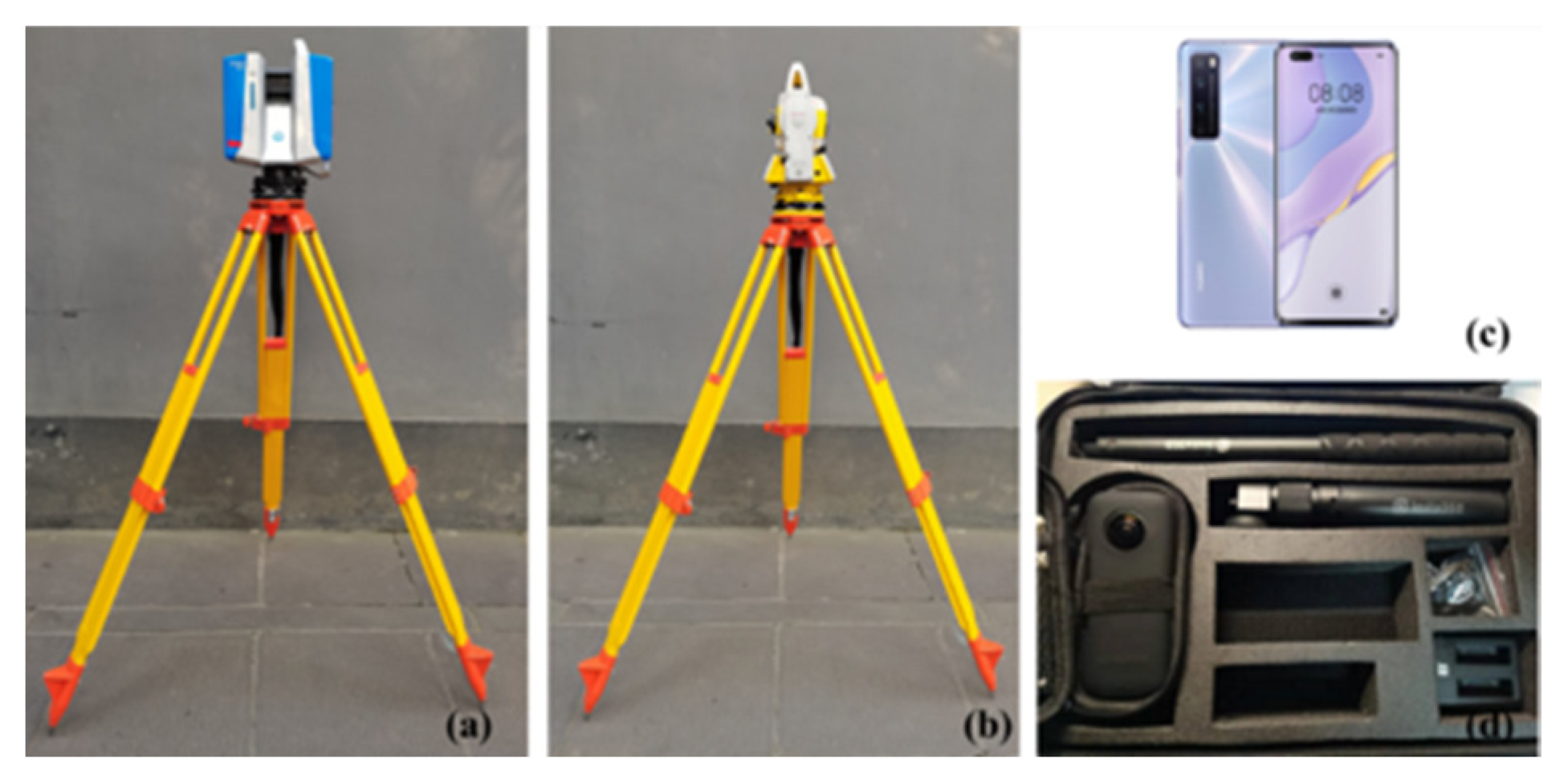

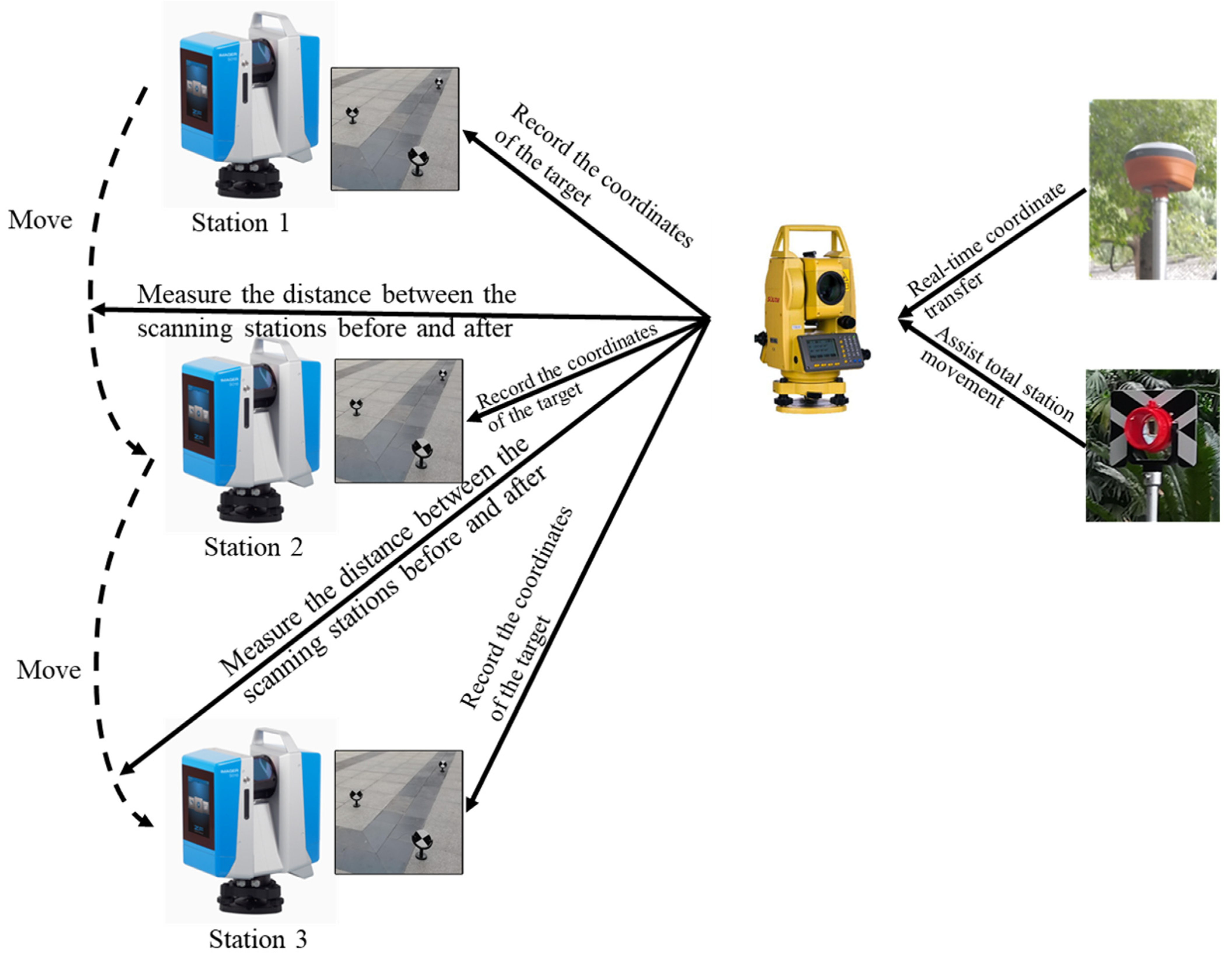

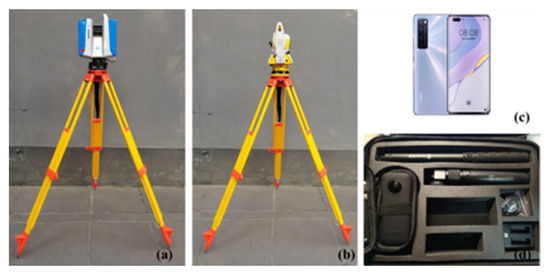

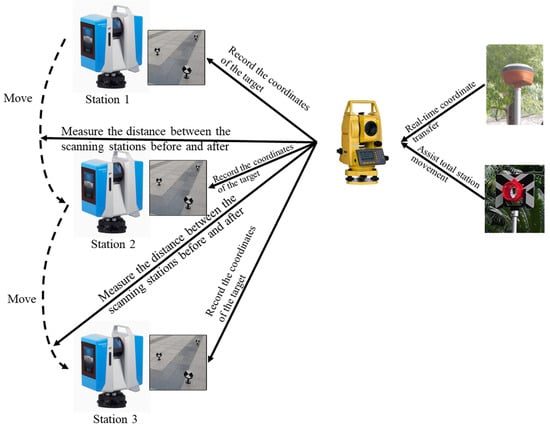

Terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) of Du Fu Thatched Cottage was conducted using Z + F IMAGER5016 (Figure 3a) and a Southern Mapping NTS-332R total station instrument (Figure 3b). Utilizing a Huawei Nova 7 Pro smartphone (Figure 3c) and the Insta360 OneX panoramic camera (Figure 3d), spatial data were captured. The terrestrial 3D laser scanner obtained 3D point cloud data for use in modeling complex surfaces and spatial levels down to the millimeter. The device comes with an 80 million pixel HD camera and gives RGB color values to the point cloud. Compared with other gardens such as Huanxiu Shanzhuang [22] and Jianxin Garden [31], one scanning equipment was used for TSL, while Du Fu Thatched Cottage added a total station to cooperate with 3D laser scanning to improve the accuracy of scanning data. Because Du Fu Thatched Cottage has more spatial data and a complex environment, its area is nine times and 3.8 times that of the two gardens, respectively. Preliminary surveying and mapping in the garden to determine the spacing for scanning is conducive to a relatively high quality and efficiency for mapping the entire garden, reducing the impact of 3D laser scanning distortions from the object material, target, inaccuracy in stitching images, and scanning distance [34]. In surveying and mapping, the total station controls the ground three-dimensional laser scanning, field survey, mapping site distance, and GPS coordinates; the complete sequence of steps is shown in Figure 4. In addition, 360-degree camera photography and mobile phone photography are convenient operations. They are used to artificially exclude the interference of tourists and external objects that are recorded by the scanner, view the spatial elements in the current situation in real-time for decision-making, and supplement data on the spatial environment that were not collected by the scanner due to element occlusion for subsequent research and analysis. The differences in digital mapping methods between Du Fu Thatched Cottage and other locations are shown in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Mapping equipment: (a) Z + F IMAGER5016; (b) NTS-332R total station; (c) Huawei Nova 7 Pro smartphone; (d) Insta360 OneX panoramic camera.

Figure 4.

Collaborative surveying of terrestrial 3D laser and total station.

Table 1.

Mapping data from Chinese classical gardens.

3.2. Site Survey and Data Collection

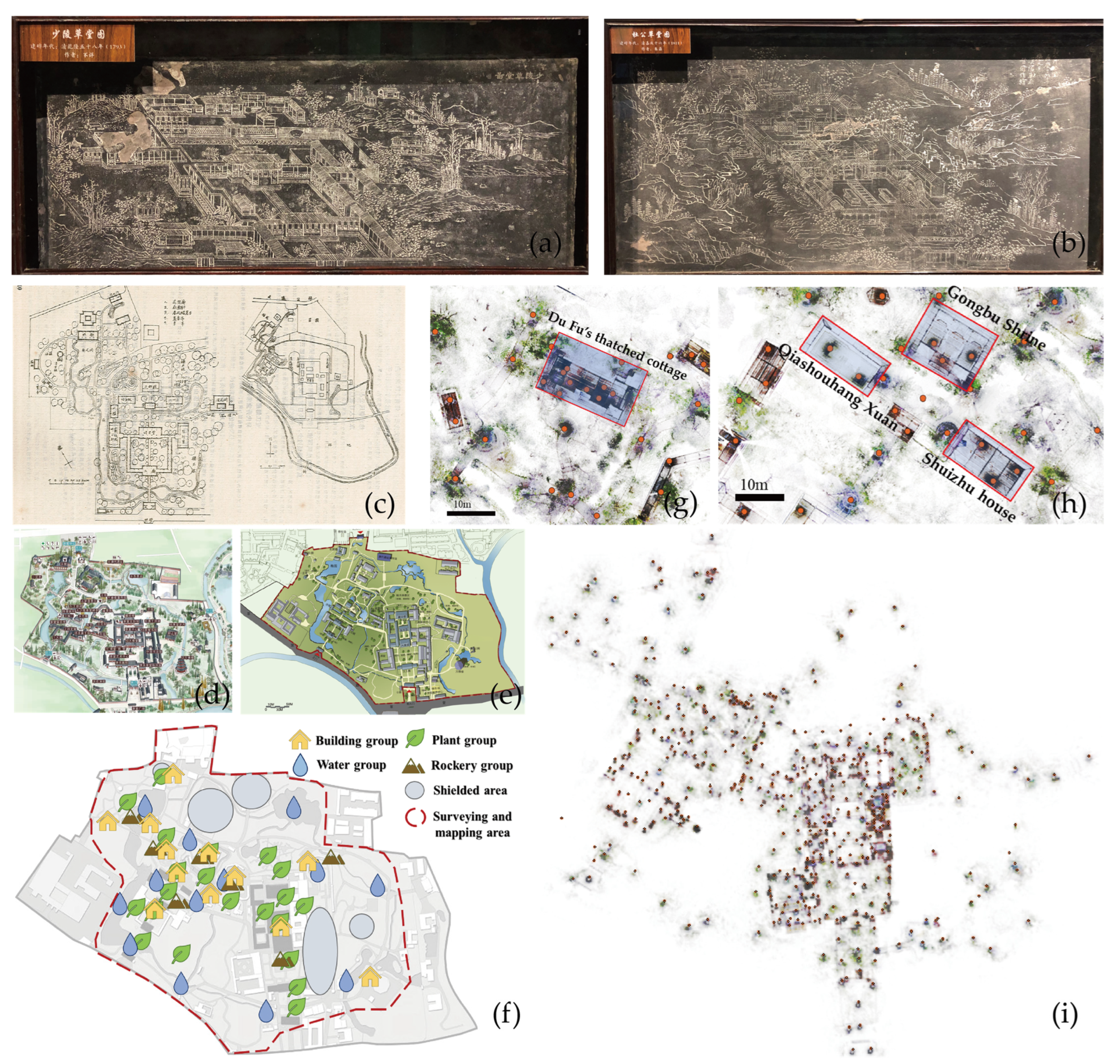

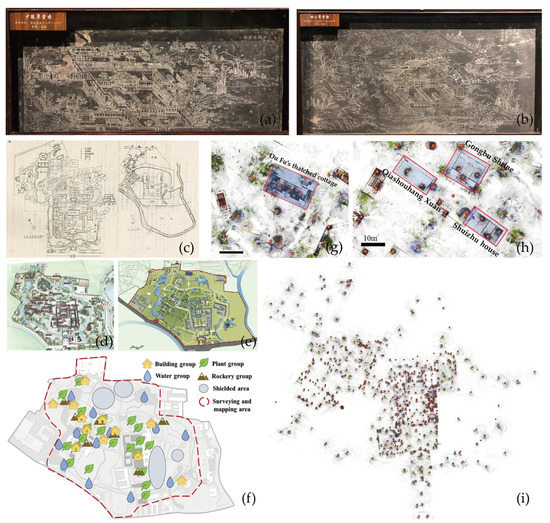

Before the implementation of surveying and mapping of the Du Fu Thatched Cottage, the historical evolution, landscape layout, and spatial relationship of the garden were analyzed. Historical data were collected including the stone carving of the Shaoling Thatched Cottage in the 58th year of the Qianlong reign (1793) (Figure 5a), the stone carving of the Dugong Cottage in the 16th year of the Jiaqing reign (1811) (Figure 5b), historical accounts in books (Figure 5c) [3], the guide map of the garden (Figure 5d) [33], the planning map for the Du Fu Thatched Cottage (Figure 5e) [33], a satellite map (Figure 1), and other materials. It was determined that three major areas would be the focus of the survey: the Gongbu Shrine area, the Thatched Cottage, and the Plum Garden. The key points of the buildings, plants, ponds, and rock formations were determined according to the layout of the current elements, as shown in Figure 5f.

Figure 5.

Historical data, mapping range, important groups, mapping stations: (a) the stone carving of Shaoling Cottage in the 58th year of Qianlong (1793); (b) the stone carving of the Dugong Cottage in the 16th year of the Jiaqing reign (1811); (c) historical accounts in books; (d) the guide map of the garden; (e) the planning map for the Du Fu Thatched Cottage; (f) the group of key points of element mapping; (g) surveying and mapping stations of thatched cottage; (h) surveying and mapping stations of some group; (i) scanning stations of the whole garden.

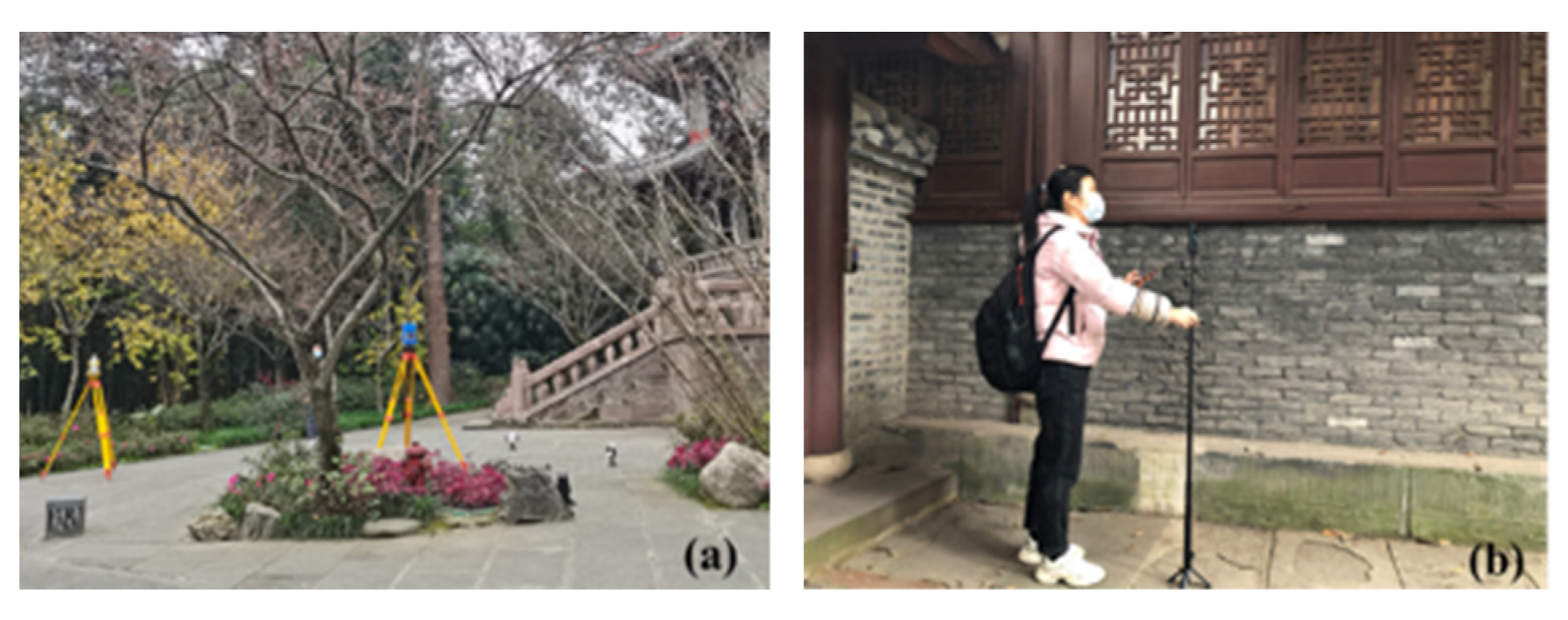

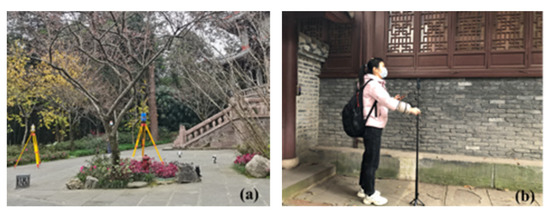

Five people mapped and surveyed the grounds of Du Fu Thatched Cottage for 18 days (Figure 6). There were 530 scanning stations, and all garden surveying and mapping stations are shown in Figure 5g–i. A total of 596 three-dimensional panoramic photos and videos were taken by panoramic camera, and more than 3000 photos were taken by mobile phone. Route mapping was combined with garden road traffic. In the surveying and mapping process, laser scanning technology with a 10 m resolution of 6.3 mm and a normal quality setting was used. When scanning, 3D laser scanning sites mainly combine the elements of form and volume to capture contiguous buildings, important trees, or water bodies to ensure that the elements of the total scene are intact. Because the water rockery, stone bridge, and other elements can only be scanned as external contours, the details of these structures including their internal and underside positions were not easy to scan; consequently, a panoramic camera and mobile phone-assisted shooting were used for subsequent analysis.

Figure 6.

Field surveying and mapping of Du Fu Thatched Cottage: (a) terrestrial laser scanning; (b) digital photography.

3.3. Data Processing

After completing the field data collection, two stages of data processing were carried out. The first stage was the basic data operation, and garden digital processing was performed in the second stage.

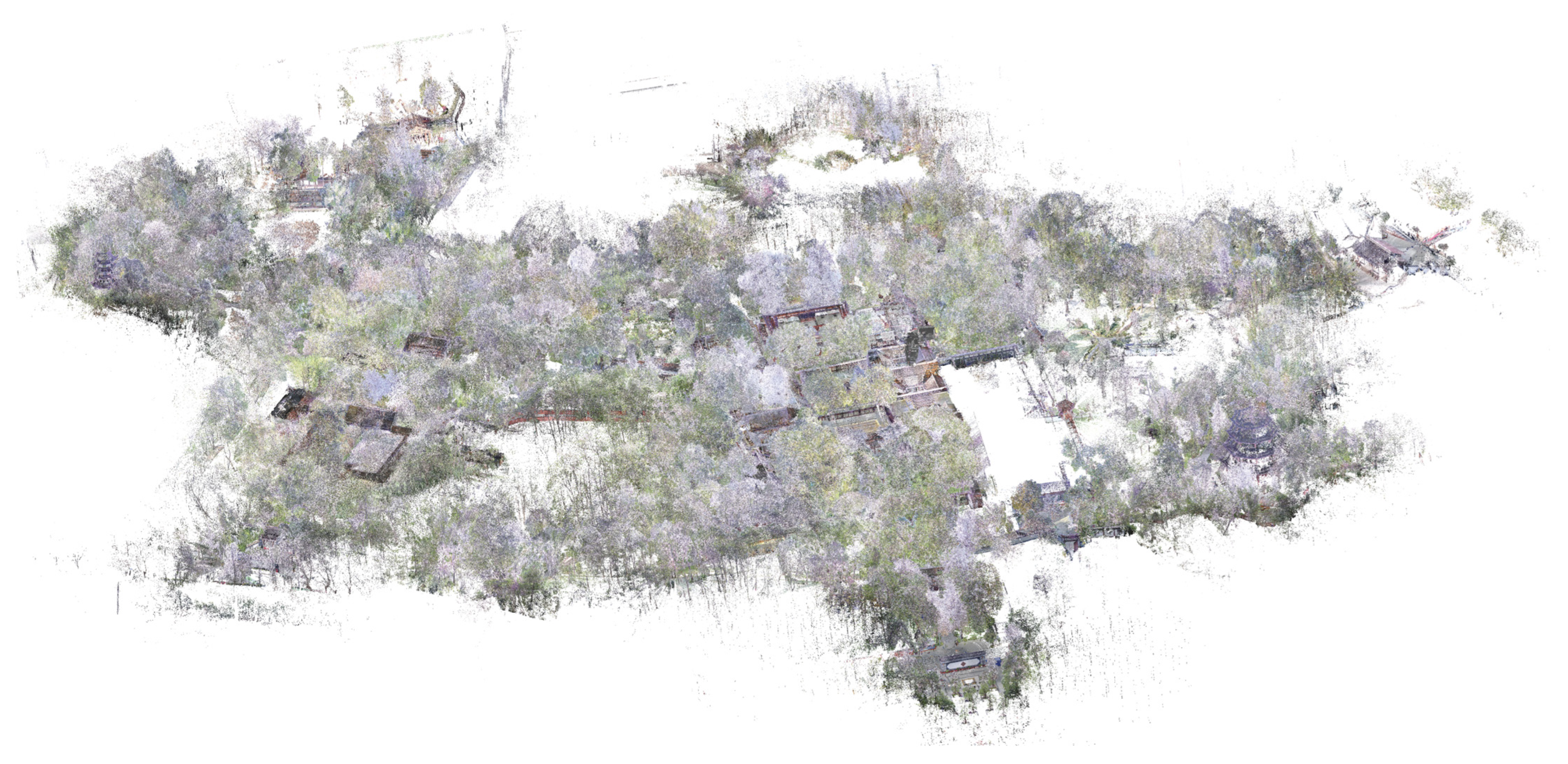

Basic data operations were mainly stitching together the point cloud data, reducing the point noise, thinning the data, and classifying the images. The data stitching was carried out primarily by using the target, coordinate, and point cloud, so that three modes of data collection from multiple stations were fused together in the point cloud, with the Du Fu Thatched Cottage point cloud stitching error set to 7 mm. Point cloud denoising was performed semiautomatically using low-pass filtering software, direct filtering, Gaussian filtering, and other automatic denoising techniques that artificially remove noise from the presence of visitors and non-garden equipment. Point cloud thinning is the adjustment of the point cloud model size by setting the minimum point cloud quantity. The whole garden point cloud as finally processed is shown in Figure 7. Photographic image classification is mainly based on buildings, plants, rocks, water, sculpture, and other classifications.

Figure 7.

Whole garden point cloud model of Du Fu Thatched Cottage.

The digital deconstruction of the garden was mainly based on detailed information analysis, both overall and at the local levels, and element processing from the perspective of the garden. It was necessary to pay attention to the extraction and analysis of spatial pattern characteristics, historical information, and special elements of the garden. The steps involved in deconstruction can be divided into three aspects. (1) The recognition and extraction of basic information such as the scale and elevation of the whole garden as well as the acquisition of plane, vertical, profile, and spatial levels on different scales; (2) The garden space was deconstructed such as spatial patterns, unit nodes, landscape sequence identification, and extraction analysis; (3) Other elements were extracted and classified including garden architecture, plants, rocks, ponds, sculptures, and other elements from point cloud models including local doors and windows, couplets and plaques, and other decorative details.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Digital Deconstruction of Garden Memorial Space

There are a variety of memorial spaces that honor the legend of Du Fu at the Du Fu Thatched Cottage. Combining the digital point cloud and panoramic image, a digital deconstruction of the garden’s “unit–sequence–layout” was made using three levels of point, line, and surface, aiming at studying the construction of memorial space in Du Fu Thatched Cottage intuitively and quantitatively.

4.1.1. Point-Memorial Space Unit

- (1)

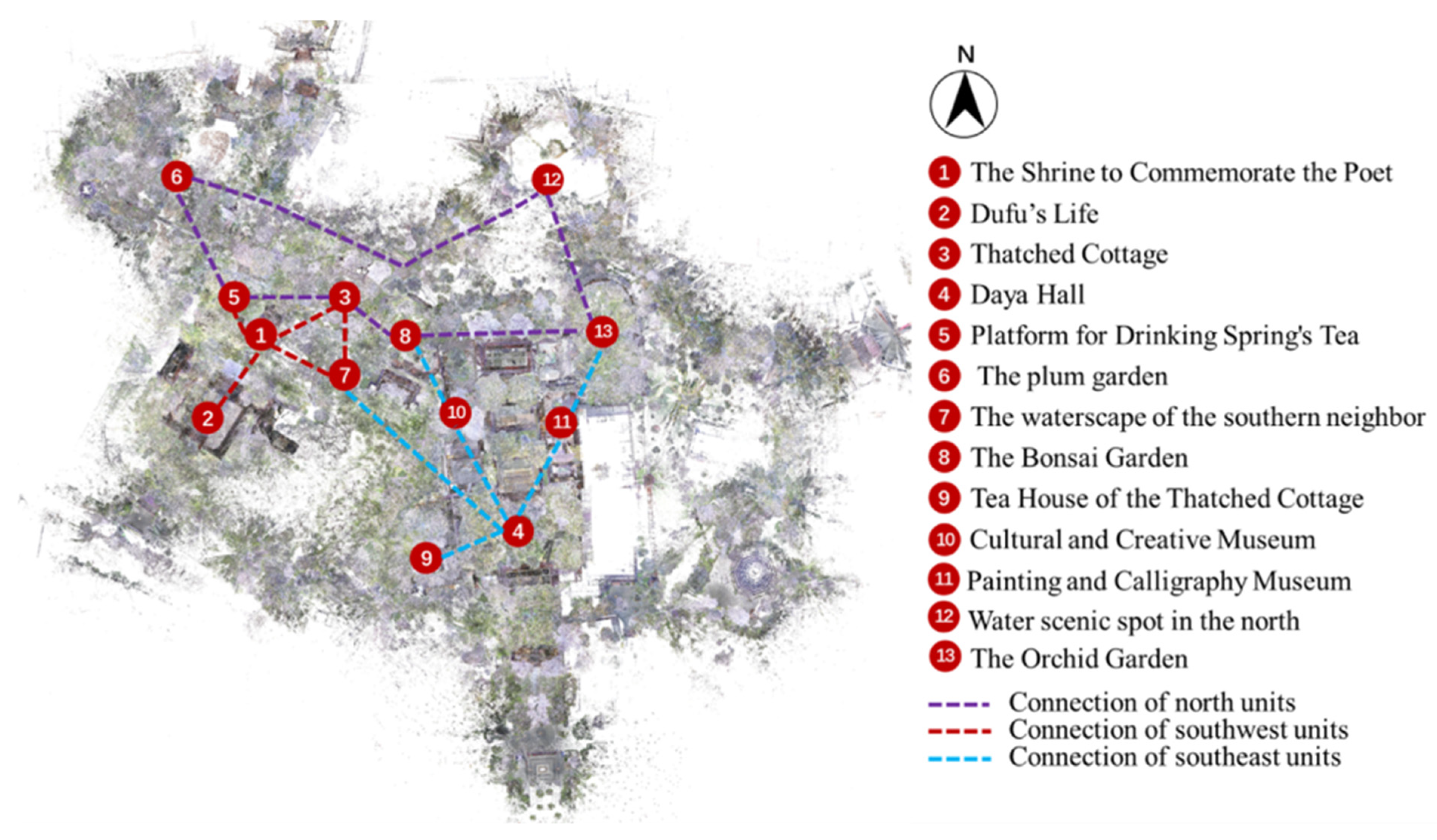

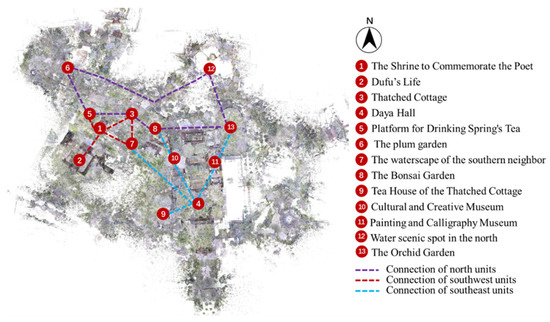

- Organizational Theme and Morphological Features

Different node themes and spatial forms create a rich memorial atmosphere. Traditional memorial gardens are often built with structures scaled to be very long, pyramid, or cemetery style compositions and repeated single elements [35]. However, in the Xishu Historical and Cultural Celebrity Memorial Gardens, a memorial atmosphere has been created that interacts with regular and natural compositions, with the integration of both compact and decentralized elements and a variety of themes. Using the whole garden point cloud data, the Du Fu Thatched Cottage can be divided into 13 commemorative space units by analyzing its spatial form, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The memorial spaces of Du Fu Thatched Cottage.

Among the 13 memorial units, there are three types: regular, natural, and mixed. Regular spatial units are represented by ①, ②, ④, ⑨, ⑩, and ⑪, which have the morphological characteristics of many elements, compact space, and symmetrical equilibrium; ③, ⑧, and ⑬ are mixed space units, which integrate regular interiors with natural exteriors to present a scene of regular buildings surrounded by natural trees or bonsai surrounded by regular peripheral corridors. Natural space units are represented by ⑤, ⑥, ⑦, and ⑫, where the layout of elements is random, with some units having a wide area, an open, unobstructed view, and many natural or wild objects of interest.

From the perspective of spatial unit organization and theme analysis, the 13 units of Du Fu Thatched Cottage use roads and walls as spatial boundaries and connections. Multiple types are coordinated to form two major thematic sequences at the Gongbu Shrine and the Caotang Temple as well as three major areas of historical commemoration, cultural display, and ecological conservation. Units ①, ②, ③, ⑤, and ⑦ are concentrated in the Gongbu Shrine area, mainly for historical commemoration, approximately 20,170 m2. Units ②, ①, and ③ in the area are a connected series that form a historical commemoration of Du Fu’s life and social status. Units ④, ⑨, ⑩, ⑪, ⑧, and ⑬ are concentrated in the Caotang Temple area, mainly for cultural display and exhibition, presenting a large compound temple courtyard pattern consistent with the styles of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, approximately 34,714 m2, with a clear landscape sequence along the temple garden axis. Units ⑥, ⑤, ③, ⑧, ⑬, and ⑫ are close to the north of the garden, with a total area of 44,595 m2. The layout of the units is scattered, involving mainly plants and waterscapes, and the ecological effect is outstanding. Moreover, unit ④ and unit ① are connected by the ‘flowered path’ (Figure 2i), which is visually resonant with the poetic line from Du Fu, “My flowered path has never yet been swept on account of a guest, my ramshackle gate for the first time today is open because of you” [2].

- (2)

- Landscape Element Configuration

The arrangement of garden elements impacts the theme and ambience of each spatial unit. Combining the historical context with the point cloud and panoramic image analysis, Table 2 shows the total area of the 13 spatial units at the memorial at Du Fu Thatched Cottage, and the area that is occupied by plants, buildings, and waterscapes, and the number of couplets, plaques, sculptures, and inscriptions for each unit. Among the commemorative spaces at Du Fu Thatched Cottage, the plum garden (⑥) occupies the largest space, followed by Du Fu’s biographical history (②), and the Chunfeng Tea Pavilion (⑤) occupies the smallest space. At the same time, buildings and plants occupy a large area among the regular units, while plants occupy a large area in natural units. Regular units have more flexible space for displaying couplets, plaques, sculptures, and inscriptions.

Table 2.

Element statistics for the spatial units at the memorial level.

Comparing the four elements of couplets, plaques, sculptures, and inscriptions in the 13 spatial units of the memorial from the perspective of configuration, the regular units represented by ①, ②, and ④ are better spaces to deploy all elements, while the mixed units represented by ⑧ and ⑬ mainly feature single elements, typically inscriptions. Couplets and plaques are the most frequently used components in the memorial garden spaces in terms of quantity, while inscriptions are the most common components across all 13 spaces. This encourages change and interest throughout the entire Du Fu Thatched Cottage memorial area.

4.1.2. Line-Changeable Memorial Landscape Tour Sequence

The most noticeable location with a commemorative atmosphere in the Du Fu Thatched Cottage is the area around the Gongbu Shrine and Caotang Temple. The landscape sequence of these two sites is used to guide commemorative analysis. The space adopts the theme of historical memorial culture and employs storytelling techniques to construct landscapes that honor Du Fu’s lifetime accomplishments.

- (1)

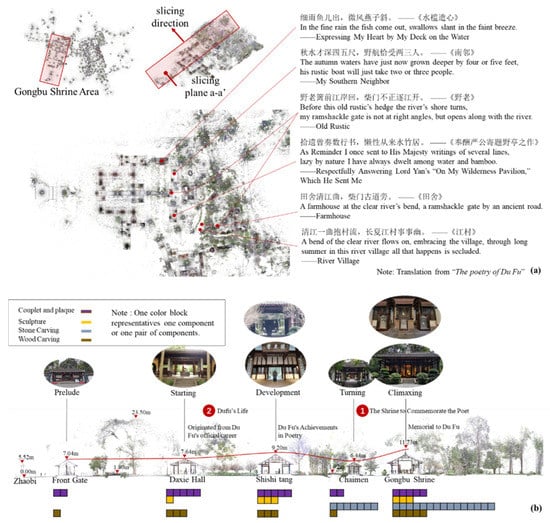

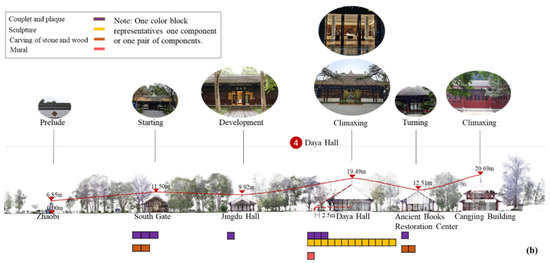

- The Gongbu Shrine Sequence

Landscape spatial analysis of the extracted Gongbu Shrine sequence is shown in Figure 9. The Gongbu Shrine sequence is approximately 207 meters long overall. Five buildings are connected by center roads, which are “Zhaobi—Front Gate—Daxie—Shishitang—Chaimen—Gongbu Shrine”, and the east and west rooms are symmetrically arranged on the left and right sides of Shishitang and Chaimen, forming a pattern of multiple courtyards and laying the solemn tone of the memorial garden (Figure 9a). Meanwhile, the architecture, couplets, plaques, sculptures, stone carvings, wood carvings, and other important commemorative elements adopt a regular configuration and poetic layout, strengthening the commemorative and cultural nature of the space. To guide and shape the commemoration, a landscape rhythm of “prelude, starting, development, turning, climaxing, and ending” was formed, which has the same interest as the Origin, Inheritance, Transformation and Combination of Chinese classical gardens [3,4,5,6].

Figure 9.

Analysis of the Gongbu Shrine Area: (a) location and zoning of Gongbu Shrine; (b) section Analysis of Gongbu Shrine.

Analyzing the landscape along the middle axis of the sequence, the memorial space is created by two aspects of theme narration and element foils. First, the narrative of Du Fu’s career and achievements is carried out in conjunction with the unit theme of ② Du Fu’s life and ① the Shrine to Commemorate the Poet such as the Gongbu Shrine and Daxie, which carry names that honor Du Fu’s official career. Shishi Tang was written to honor Du Fu’s eminent place in the Chinese history of poetry. Second, by changing the height and distance of the buildings along the serial axes, the number and type of key commemorative elements and the poetic materialization of the landscape are superimposed and adjusted to change the commemorative space and make the memorial atmosphere reach a peak. For instance, the total number of commemorative components such as couplets, plaques, sculptures, and woodcuts gradually grows with the height of the first three buildings, permitting commemorative development. Reduced building volume and increased couplet inscriptions help to move the sequence toward the turning point and create a sense of fully transformed space. When the sequence reaches its climax, the height of the building in unit ① increased significantly to 11.73 m, and the distance of 19.59 m to the next building is also spaced more tightly than the distance between the buildings for Du Fu’s life in unit ②, which are 35 m apart. Additionally, more stone carvings, wood carvings, sculptures, and other elements were added to emphasize the historical memorial atmosphere of the thick building (Figure 9b).

The arrangement of the building and surroundings in the series also places an emphasis on poetry and painting, which is consistent with the cultural ethos of Du Fu’s poetry. For instance, the names of the rooms on either side of the Chaimen and waterside building and even the location of the Chaimen and the Thatched Cottage were inspired by Du Fu’s poetry. These poems include “Expressing My Heart by My Deck on the Water”, “My Southern Neighbor ”, “Old Rustic”, “Respectfully Answering Lord Yan’s “On My Wilderness Pavilion,” Which He Sent Me”, “Farmhouse”, and “River Village” [2].

- (2)

- The Caotang Temple Sequence

The spatial analysis of the landscape in the Caotang Temple sequence is shown in Figure 10. The Caotang Temple is large in scale and has a clean, neat form. Through the evolution and development of the planning layout, the internal elements and functions show the exploration and development of the integration of ancient and modern memorial gardens. This sequence spans a surface area of approximately 24,183 m2 and measures a total length of 245 m. A four-entry courtyard with the buildings “Zhaobi—South Gate–Jingdu Hall–Daya Hall—Ancient Books Restoration Center—Cangjing Building” makes up the sequence along the central axis. Wenchuang Hall, Caotang Academy, Caotang Tea House, Bonsai Garden, and Orchid Garden are separated on the left and right sides to create a vast compound temple courtyard pattern. Through the analysis of the courtyard area, Caotang Temple embodied the old custom of building a compound courtyard in the spirit of respect and the main–subsidiary relationship. For example, the affiliated courtyard Wenchuang Hall of Caotang Academy covers approximately 25% of the total area of the four middle courtyards, with a cottage teahouse occupying approximately 28%, reflecting the core position in the area of Daya Hall. The courtyard in front of Daya Hall was not only the squarest of the four courtyards, but also covered approximately 42% of the total area of the four courtyards (Figure 10a).

Figure 10.

Analysis of the Caotang Temple Area: (a) location and zoning of Caotang Temple; (b) Section Analysis of Caotang Temple.

The height of the buildings in the entire sequence was enhanced twice, continuing the ritualistic qualities of the temple building axis, according to the analysis of the façades in sequence. Thus, the axis was centered on the third building (Daya Hall) and the last building (Cangjin building), which were the highest at 19.49 m and 20.69 m, respectively. To represent the main–subsidiary connection, the height of the buildings on each side of the courtyard did not exceed the height of the main building. Crucial spatial detail processing in the sequence also suggests the presence of a creative design to direct and reflect memorial elements. For instance, Daya Hall has the richest commemorative elements in the sequence (Figure 10); in front of the hall is a sculpture of Du Fu. The line of sight and the horizontal line on Du Fu’s head are at an approximate 30° angle when the tourist is standing approximately 2.5 metres in front of Du Fu’s sculpture. They can also make out the ridge in the middle of the hall as the line of sight rises, emphasizing the significance of the hall (Figure 10b). The sculpture guides visitors to the auditorium to look at the largest glazed lacquer murals depicting Du Fu’s life and the group of poets that Du Fu, Li Bai, and Su Shi symbolize. Additionally, the courtyard of this sequence differs from the courtyard of the Jiangnan garden, which has numerous rock installations. This courtyard is unique in part because it is conspicuous, and the historical significance and unique qualities of Sichuan’s luxuriant plants are highlighted in the courtyard by the addition of true natural color and growth in the understorey space beneath the old trees.

4.1.3. Surface-Memorial Functional Zoning: Ancient and Modern Fusion

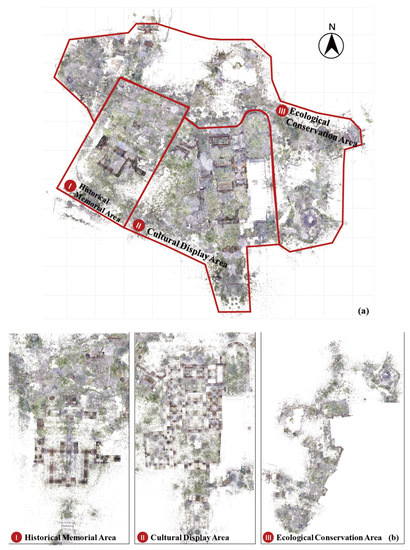

To honor Du Fu, the entire garden of Du Fu Thatched Cottage has been divided into three main areas: historical remembrance, cultural display, and ecological conservation (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Functional partition of Du Fu Thatched Cottage: (a) functional partition; (b) area function.

The historical memorial area consists of units ①, ②, ③, ⑤, and ⑦ as a significant place of sacrifice and remembrance. The neighborhood still has various cultural collections of artifacts, along with the historical records of the design of the Du Fu Thatched Cottage from the Ming and Qing dynasties. To give the setting a commemorative feel, a concentration on Du Fu’s identity, consisting of his official career, poetic accomplishments, and life, influences the naming of buildings, display layouts, flowers, plants, and trees.

Units ④, ⑨, ⑩, ⑪, ⑧, and ⑬ make up the cultural display area. This serves as a key location for the garden as a whole to present and solidify Du Fu culture, encouraging the continuation of the traditional cultural theme and offering services such as traditional cultural activities, poetry, calligraphy, picture book reading, cultural creation, exhibition, marketing, tea, and rest. The left and right dynamic and static partitions of the area, which include the cottage academy, the cultural and artistic hall, and the cottage tea house, are distributed using the four courtyards along the center axis as their core axis. A vast number of compound courtyards surround the center courtyard including the gallery of Du Fu’s thousand poems and the woodcut poetry of the Bonsai Garden. Around the area commemorating Du Fu, this section expands on the topic of protecting historical and cultural relics, cultural events, and services, producing an environment that emphasizes the literati aesthetic and a theme of integrating ancient and current culture.

Units ⑥, ⑤, ③, ⑧, ⑬, and ⑫ constitute the ecological conservation area. The primary purpose of ecological regulation is to keep the entire garden water system flowing and in balance. The water source from the Huanhuaxi River is introduced into the north waterscape around the northeast sides of the two main areas of historical commemoration and cultural exhibition, and the ditch is used to connect the water flow through the entire garden to form a rich and natural waterscape with green plants. Through the road connecting the corridor of Du Fu’s thousand poems, the Bonsai Garden, and the Gongbu Shrine, the area simultaneously links the natural landscape with Du Fu’s poetic culture, giving visitors a place to experience both. It also lessens the memorial garden’s solemn, compact feeling, and strongly humanistic atmosphere while demonstrating the garden’s inclusiveness and naturalness.

4.2. Construction and Discussion of the Garden Digital System

4.2.1. Digital Preservation Kernel

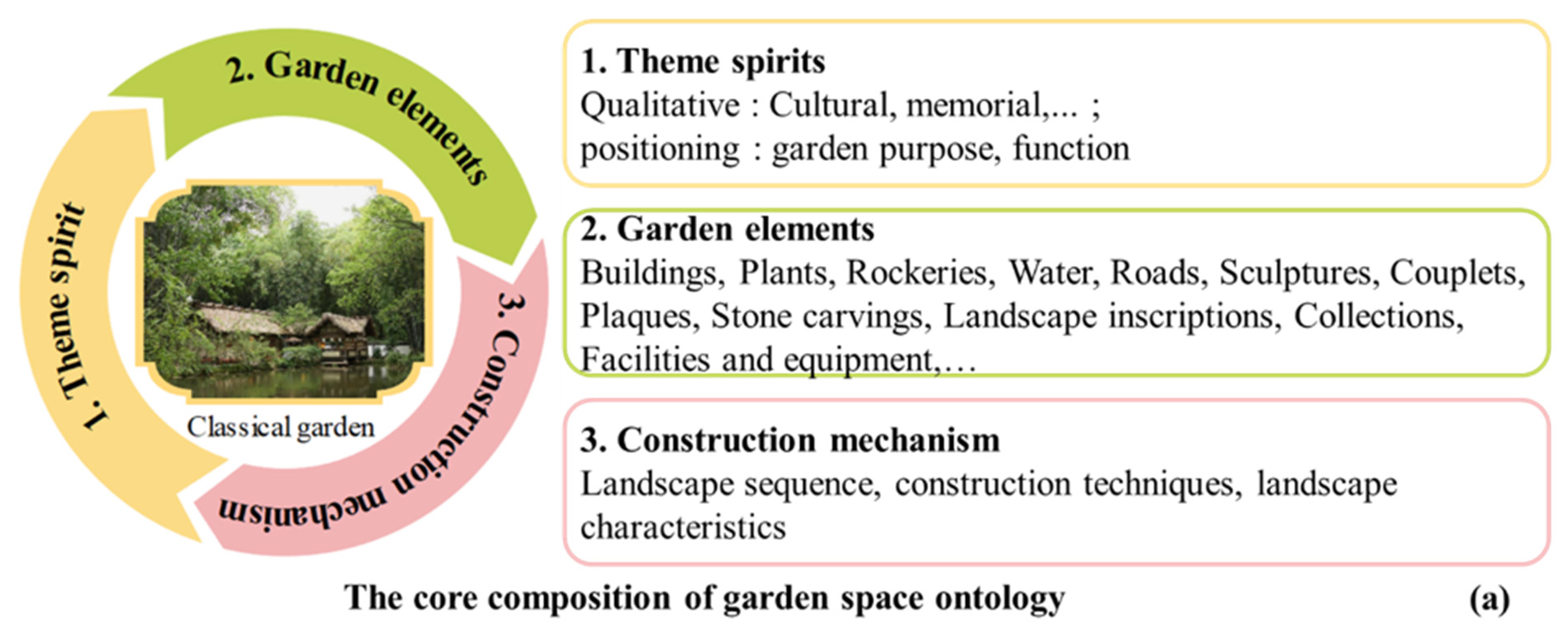

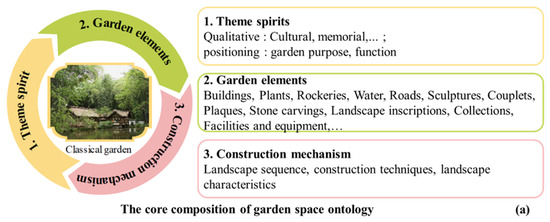

The garden space ontology, which is made up of garden theme spirits, garden elements, and construction techniques, is the basis of digital preservation for classic gardens (Figure 12a). The Xishu Historical and Cultural Celebrity Memorial Gardens, which has a memorial garden theme, is under the category of cultural gardens and features a variety of garden components such as buildings, plants, rocks, waterscapes, roads, sculptures, couplets, and plaques. Its eclectic construction methods, landscape features with garden texts, and design sequence with story clues together make up the philosophy of construction, and collectively create a memorial space with distinctive regional traits and cultural styles.

Figure 12.

Digital preservation process system of classic gardens: (a) the core composition of garden space ontology; (b) digital landscape protection process.

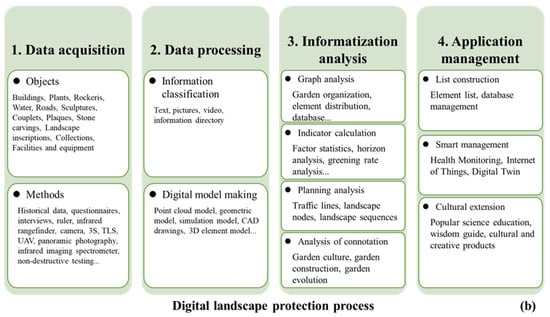

4.2.2. Digital Preservation Process

A digital preservation system for classical gardens can be established around the core using references to BIM [36], HBIM [37], and LIM [38] of the complete life cycle idea and mapping, modeling, information processing, and other digital concepts and technologies. The four stages of the life cycle of digital preservation for classical gardens are data collection, processing, information analysis, and application administration (Figure 12b).

The first stage primarily combines the spirit of the garden with the building process, employing classic surveying and mapping techniques as well as cutting-edge digital tools to carry out actual data mapping and collect garden materials for later analysis. The second stage mostly involves data processing including data classification and the creation of digital models. For instance, the textual and visual representations of the garden’s features can be categorized and arranged, and the entire garden can be represented as a point cloud model or as digital artwork with a 3D element. The third stage involves the information analysis of the garden’s connotations based on the original data including the creation of a map of the garden’s information, the calculation of the garden index, and the analysis of the planning and design. The fourth stage mainly integrates digital technology, early garden data, the analysis results to carry out garden list construction, encourage intelligent management with tools related to health monitoring, the Internet of Things, digital twins, etc., and carry out garden culture education, as shown in Figure 12.

4.2.3. Characteristics and Difficulties

The digital preservation system of the Xishu Historical and Cultural Celebrity Memorial Gardens can be constructed based on the composition and design of the garden memorial space. The existing digital records of classical gardens such as Huanxiu Shanzhuang and Jianxin Courtyard, mostly classify and analyze gardening elements, establish three-dimensional digital models, and pay insufficient attention to the overall spatial organization and sequential configuration [9,22,31]. “The Venice Charter” (1964) and “The Nara Document on Authenticity (1994)” mentioned that cultural heritage preservation should focus on authenticity, integrity, and diversity [39]. Compared with Western classical gardens and ancient sites, Chinese classical gardens are rich in symbolic elements, diverse in construction methods, vivid in artistic conception, emphatic on integration with the environment, and attentive to the overall ambience [3,4,5,40]. Although the digital deconstruction of Du Fu Thatched Cottage focuses on the integrity and diversity of themes, that is, the memorial units, elements in the landscape sequence, and the role of construction in shaping the spatial environment, it proposes a strategy for building a digital system based only on this one example and has not yet established a mature information model.

At the same time, the existing cases and the digital practice of recording Du Fu’s cottage show that large and complex gardens still need multimode and multi-technology coordination in digital surveying and mapping. Although digital technology is universal, the emerging digital technology can obtain real, multidimensional data at the millimeter level for complex space and simulate and analyze the structural performance [10,41]. However, the irregular and natural characteristics of Chinese classical gardens are very prominent. There is a lack of guidance for an established process for the digitization of gardens with the application of digital technology, and it is also difficult to carry out comprehensive research on ancient sites and ancient buildings with digital techniques based on single-type elements as before. For example, Huanxiu Shanzhuang can use UAV and 3D laser scanning to coordinate mapping, but Du Fu Thatched Cottage is not suitable for UAVs due to air management. Although Du Fu Thatched Cottage uses ground three-dimensional laser scanning and total station collaborative mapping to improve the collection quality and accuracy, data on the tops of local elements are still missing. In addition, digital processing has high requirements for the professionals, hardware, and software. It often requires the cooperation of many professionals such as those involved in surveying and mapping and those involved in landscaping as well as a variety of professional software and high-performance hardware support.

From the perspective of the construction of garden digital systems, classical Chinese gardens are characteristically emblematic of both history and culture and have complex and large-scale characteristics in garden scenes. There are few applicable information models and digital systems that can handle this diversity of elements. This paper proposes that the construction of a digital preservation system for classical gardens can be based on the garden space ontology after data collection, processing, analysis, and management. Although the building information model (BIM) [36,42,43] and the historical building information model (HBIM) [37,44,45,46] are worth learning, BIM is mainly aimed at the whole life cycle and regular elements of the building and the production and application of the database [42]. However, there are a large number of irregular and dynamic elements in gardens aside from buildings such as plants and waterscapes as well as the relationship between different regions and elements, which increases the difficulty of establishing a model for management. HBIM takes BIM as its core, adding historical information and elements with irregular features, but its model scene is still dominated by architecture, with few large-scale landscapes. In recent years, scholars have studied the landscape information model (LIM) [38,47,48,49], which is still in the stage of concept proposal and multi-software collaborative exploration and application, and there is still a lack of supporting software tools and skills. Classical gardens are, however, still limited, as they cannot completely copy the LIM model due to the particularity of historical relics and the characteristic semi-reverse information model. In addition, most studies on city information modeling (CIM) have focused on the seismic performance of buildings with large populations [24], the digital display of elements [26], and platform development [50], and rarely involve the simulation of historical and cultural sites and the comprehensive performance of different elements such as the overall response of famous trees and ancient buildings with cultural heritage to earthquakes.

5. Conclusions and Future

5.1. Conclusions

Based on the digital surveying and mapping results for Du Fu Thatched Cottage, this paper analyzed the relationship between the commemorative construction of the gardens in Du Fu Thatched Cottage and the disposition of the theme, element configuration, and planning of the garden using digital methods. It also proposes strategies for building a digital preservation system for gardens. The analysis shows that Du Fu Thatched Cottage is constructed around the theme of commemorating Du Fu. In the commemorative construction of the garden, elements such as couplets, sculptures, and stone carvings are widely used in commemorative units and sequence nodes to emphasize the atmosphere. The height and area of the buildings are intentionally controlled, emphasizing the importance of the center and an architecturally embodied etiquette. Meanwhile, its digital preservation system should pay attention not only to the elements of gardening, but also to the garden space ontology formed by the spirit and design of the garden plan.

The innovation of this paper lies in two points: (1) Compared with traditional garden analysis, the digital technology adopted this time had more perspectives and more comprehensive garden data; and (2) with the help of digital technology, digital analysis was carried out according to the landscape planning method, which has been relatively rare in previous classical garden analysis. It is proposed that the digital preservation of the Xishu Historical and Cultural Celebrity Memorial Gardens should focus on the memorial spirit, and the model of spatial deconstruction by unit, sequence, and area of the garden’s core memorial ontology should be established.

5.2. Future

Digital preservation covers a wide range of cultural sites with a comprehensive approach, but the digital preservation for the type of garden represented by the Xishu Historical and Cultural Celebrity Memorial Gardens is still in the primary exploration stage. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss digital practice in combination with Du Fu Thatched Cottage in the future.

First, in the practice of the digital preservation of Du Fu Thatched Cottage, the theme of the garden’s core spirit should become the key axis guiding research on digital preservation for gardens. The Xishu Historical and Cultural Celebrity Memorial Gardens are different from royal or private gardens. The purpose of their construction is not to meet the private needs of emperors or literati, but to commemorate the valuable conduct, deeds, and talents of historical celebrities [3,5,51]. They have an open, inclusive, and spontaneous public quality and carry common spiritual guidance; thus, there are more commemorative subthemes and public activity spaces in gardens. Therefore, digital mapping and analysis should combine the characteristics of garden culture, commemorative goals, heritage conservation, and the theme of the garden. At the same time, we should also pay attention to the differences between the main celebrities in the Xishu Historical and Cultural Celebrity Memorial Gardens. For example, the garden management at Du Fu Thatched Cottage always pays attention to Du Fu’s life experience, love of plants, and the spirit of caring for the country and the people, while Chengdu Wuhou Shrine pays attention to Zhuge Liang’s identity as a virtuous minister and the characteristics of the only common sacrifice to the monarch and ministers in China. Wangjianglou Park highlights Xue Tao’s love for bamboo. These factors all affect the layout and element configuration of the memorial garden space and indirectly affect the scope and focus of data collection and post-data processing and analysis.

Second, for the digital analysis of classical gardens, it is easy to ignore the relevance and integrity between different regions and elements if the structural analysis is carried out by single-type elements. In the study of garden digitalization, this paper attempts to divide and cut spatial units and sequences in combination with the theme of the garden memorial. From the multiple levels of point (unit), line (sequence), and surface (area), the memorial ontology of the space of Du Fu Thatched Cottage was deconstructed. To explore the interrelation with cultural coding in landscape conception, element configuration, and space construction, this paper attempted to construct a preliminary process and method of the digital analysis of gardens to provide a reference point and data for subsequent, in-depth studies of a garden digital preservation system. This is conducive to the overall preservation of historical gardens, but this study is only an important early step in garden digital preservation and cannot fully meet the requirements of garden preservation and management. To protect more classical gardens and meet the challenges of digital preservation and garden management, it is necessary to increase the digital surveying and mapping, digital analytical research, and disaster simulation research of different types of gardens in the future. The establishment of digital information models should be accelerated, and digital platforms should be developed to enrich the core data on different types of gardens. A systematically constructed database will assist with the digital information model and the establishment of a digital preservation system for classical gardens.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G., J.X. and Z.Z.; Methodology, L.G., J.X. and J.L.; Software, J.X.; Validation, L.G. and Z.Z.; Formal analysis, L.G., J.X. and J.L.; Investigation, L.G., J.X., J.L. and Z.Z.; Resources, L.G. and J.X.; Data curation, J.X. and J.L.; Writing—original draft preparation, L.G., J.X. and J.L.; Writing—review & editing, L.G., J.X., J.L. and Z.Z.; Visualization, J.X.; Supervision, L.G. and Z.Z.; Project administration, L.G.; Funding acquisition, L.G., L.G. and J.X. contribute equally as co-first authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the fund of the Digital Preservation of Xishu Gardens (TY2021H01).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers for carefully reading our manuscript and for their constructive remarks.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Qin, P. Political Rituals, Cultural Heritage and National Identity—A Survey of the “Commemoration of World Cultural Celebrities” in New China’s Literary and Art Circles from 1952 to 1963. Theory Crit. Lit. Art 2022, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, S. The Poetry of Du Fu; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yang, Y. Xishu Gardens; China Forestry Press: Beijing, China, 2010; ISBN 9787503857676. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C. Xishu Historical Celebrity Memorial Gardens; Sichuan Science and Technology Press: Chengdu, China, 1989; pp. 21–53. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y. Analysis of Chinese Classical Gardens; China Construction Industry Press: Beijing, China, 1986; ISBN 7-112-00360-1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. Chinese Garden Appreciation Dictionary; East China Normal University Press: Shanghai, China, 2001; ISBN 7-5617-1775-X. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J. Research on Celebrity-Memorial Garden in West Sichuan and Its Memorial. Master’s Thesis, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China, 2008; p. 6. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD2009&filename=2008198331.nh (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- Zhou, Q.; Yan, W.; Yang, X.; Ji, J. Earthquake Damage of Ancient Buildings Caused by Wenchuan Earthquake. Sci. Cons. ARC 2010, 22, 37–45. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=WWBF201001011&DbName=CJFQ2010 (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- The Swedish Pompeii Project. Available online: http://www.pompejiprojektet.se/index.php (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Oreni, D.; Brumana, R.; Della Torre, S.; Banfi, F.; Barazzetti, L.; Previtali, M. Survey turned into HBIM: The restoration and the work involved concerning the Basilica di Collemaggio after the earthquake (L’Aquila). ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2014, II-5, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Hang, F.; Liu, C. Research on Methods for Recording and Visualising Spatial Information of Rural Landscape Heritage with Point Cloud Technology. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 25, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redweik, P.; Marques, F.; Matildes, R. A strategy for detection and measurement of the cliff retreat in the coast of algarve (portugal). EARSeL eProc. 2008, 7, 92–104. [Google Scholar]

- Barontini, A.; Alarcon, C.; Sousa, H.S.; Oliveira, D.V.; Masciotta, M.G.; Azenha, M. Development and Demonstration of an HBIM Framework for the Preventive Conservation of Cultural Heritage. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2021, 16, 1451–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hu, F. Research on the Heritage Monitoring of the Rockery in the Mountain Villa with Embracing Beauty. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 37, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zhang, Q. A review of three-dimensional digital surveying and information management for garden cultural heritages. J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 44, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liang, H.; Li, W.; Yang, M.; Zhu, L.; Huang, A. Research of the application of digital survey techniques in private garden. J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 42, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yang, C.; Han, F. Research on digital record and innovative Conservation of Cultural Landscape Heritage. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 36, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Gu, X.; Jan, W. The Application of digital 3D technology in garden surveys: Rockwork as a Case Study. J. Archit. 2016, S1, 35–40. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=JZXB2016S1007&DbName=CJFQ2016 (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Yu, M.; Lin, X. Study on the Surveying Methods Based upon the 3D Laser Scanning and Close-range Photogrammetry Techniques of the Rockery and Pond in the Classical Chinese Gardens. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2017, 2, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.A. From ground surveying to 3D laser scanner: A review of techniques used for spatial documentation of historic sites. Journal of King Saud University. Eng. Sci. 2011, 23, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.H.; Hong, S. Three-Dimensional Digital Documentation of Cultural Heritage Site Based on the Convergence of Terrestrial Laser Scanning and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Photogrammetry. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Li, W.; Lai, S.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Q. The integration of terrestrial laser scanning and terrestrial and unmanned aerial vehicle digital photogrammetry for the documentation of Chinese classical gardens—A case study of Huanxiu Shanzhuang, Suzhou, China. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 33, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, A.; Manuel, A.; Stefani, C.; Luca, L.D.; Veron, P. 2D/3D semantic annotation towards a set of spatially-oriented photographs. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2013, XL-5-W2, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redweik, P.; Teves-Costa, P.; Vilas-Boas, I.; Santos, T. 3D City Models as a Visual Support Tool for the Analysis of Buildings Seismic Vulnerability: The Case of Lisbon. Int. J. Disast. Risk. Sci. 2017, 8, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassandro, P.; Lepore, M.; Paribeni, A.; Zonno, M. 3D Modelling and Medieval Lighting Reconstruction for Rupestrian Churches. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-2/W9, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redweik, P.; Reis, S.; Duarte, M.C. A digital botanical garden: Using interactive 3D models for visitor experience enhancement and collection management. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Ge, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, G.; Chen, X. The Fractal Quantitative Analysis to the Contour Line of Rockery Composite Elements of Mountain Villa with Embracing Beauty. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 37, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hu, J. Qianlong Garden in Digital Vision; China Architecture Press: Beijing, China, 2018; ISBN 9787112212545. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H. Three—Dimensional Digital Information Research for the Garden of Huanxiu Shanzhuang, Suzhou, China. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China, 2018. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CDFDLAST2019&filename=1019600140.nh (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Yang, C.; Han, F. Digital Heritage Landscape: Research on Spatial Character of the Grand Rockery of Yuyuan Garden in Shanghai Based on 3D Point Cloud Technologies. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 34, 20–24. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=ZGYL201811005&DbName=CJFQ2018 (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Jia, S.; Liao, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Meng, X.; Qin, K. Methods of Conserving and Managing Cultural Heritage in Classical Chinese Royal Gardens Based on 3D Digitalization. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, L. 3D scanning, modeling, and printing of Chinese classical garden rockeries: Zhanyuan’s South Rockery. Herit. Sci. 2020, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengdu Dufu Thatched Cottage Museum [EB/OL]. Available online: http://www.cddfct.com/index.php (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Cao, X.; Zhang, S.; Si, H.; Meng, X.; Liu, Y. The influence factors and control measures on point cloud data precision of ground three-dimensional laser scanning. Eng. Sur. Map. 2014, 23, 5–7+11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Jiang, S. Analysis of Visual Features of memorial landscape. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2012, 28, 22–30. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=ZGYL201203007&DbName=CJFQ2012 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Kim, K.P.; Freda, R.; Nguyen, T.H.D. Building Information Modelling Feasibility Study for Building Surveying. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; Mcgovern, E.; Pavia, S. Historic building information modelling (HBIM). Struct. Sur. 2015, 27, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. On the Concept and Technology Application System of Landscape Information Modeling. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 36, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, L. Authenticity in Architecture Heritage Protection: Combined with “Venice Charter”, “Nara Document on Authenticity” and “Beijing Document”. J. Archit. 2011, 85–87. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=JZXB2011S1019&DbName=CJFQ2011 (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Ji, C.; Zhao, N. Yuanye Illustration; Shandong Pictorial Press: Shandong, China, 2003; ISBN 7-80603-691-1. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero-Tejedor, T.R.; Arqués Soler, F.; López-Cuervo Medina, S.; de la O Cabrera, M.R.; Martín Romero, J.L. Documenting a cultural landscape using point-cloud 3d models obtained with geomatic integration techniques. The case of the El Encín atomic garden, Madrid (Spain). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e235169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Dong, L. Application Study on Building Information Model (BIM) Standardization of Chinese Engineering Breakdown Structure (EBS) Coding in Life Cycle Management Processes. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 1581036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barazzetti, L.; Roncoroni, F. Generation of a Multi-Scale Historic BIM-GIS with Digital Recording Tools and Geospatial Information. Heritage 2021, 4, 3331–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brutto, M.L.; Ebolese, D.; Fazio, L.; Dardanelli, G. 3D survey and modelling of the main portico of the Cathedral of Monreale. In Proceedings of the 2018 Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage (MetroArchaeo), Cassino, Italy, 22–24 October 2018; pp. 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, S.; Musicco, A.; Fatiguso, F.; Dell’Osso, G.R. The Role of 4D Historic Building Information Modelling and Management in the Analysis of Constructive Evolution and Decay Condition within the Refurbishment Process. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2021, 15, 1250–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, G.; Mateus, L.; Fernández, J.; Ferreira, V. A Scan-to-BIM Methodology Applied to Heritage Buildings. Heritage 2020, 3, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enwright, N.M.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Osland, M.J.; Feher, L.C.; Borchert, S.M.; Day, R.H. Modeling Barrier Island Habitats Using Landscape Position Information. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y. Prospect of the Application of Digital Landscape Technology in the Field of Landscape Architecture in China. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 28, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenaux, A.; Murphy, M.; Pavia, S.; Fai, S.; Molnar, T.; Cahill, J.; Lenihan, S.; Corns, A. A review of 3d gis for use in creating virtual historic dublin. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-2/W9, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Huang, H.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C.; Fan, L.; Guo, F. Selecting Optimal Combination of Data Channels for Semantic Segmentation in City Information Modelling (CIM). Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silbergeld, J. Beyond Suzhou-Region and Memory in the Gardens of Sichuan. Art Bull. 2004, 86, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).