Abstract

In the past 10 years, the implementation of grassland ecological compensation policy has played an important role in the sustainable development of the pastoral economy. How much impact on herders will delineating the ecological conservation redline have? Such delineation is significant for the smooth implementation of the ecological conservation redline. Based on this, taking the three banner counties with a large area under the control area of the ecological redline of the Xilin Gol as examples, OLS and quantile regression were used to analyze the impact of a grassland ecological compensation policy on herdsmen’s income level, and the ordered Probit model was used to analyze the influencing factors of herdsmen’s satisfaction with the policy. The results show that: (1) grassland ecological compensation has a significant positive impact on low-income herders in ecological protection redline areas; (2) grassland ecological compensation, income and the implementation of current policy have a positive impact on the satisfaction of herders in the redline area; (3) herdsmen are highly satisfied with the grassland ecological compensation policy, but there is still a lot of room for improvement in the compensation policy after the redline is delineated. In this regard, we should increase compensation for areas with a high proportion of ecological conservation redlines, and explore ways to increase income from animal husbandry products. At the same time, we should strengthen the publicity of ecological protection redline policies and promote the timely disbursement of funds, reconstruct the grassland ecological compensation mechanism by strengthening policy incentives and hardening regulatory constraints, and effectively improve the policy efficiency of ecological protection redlines.

1. Introduction

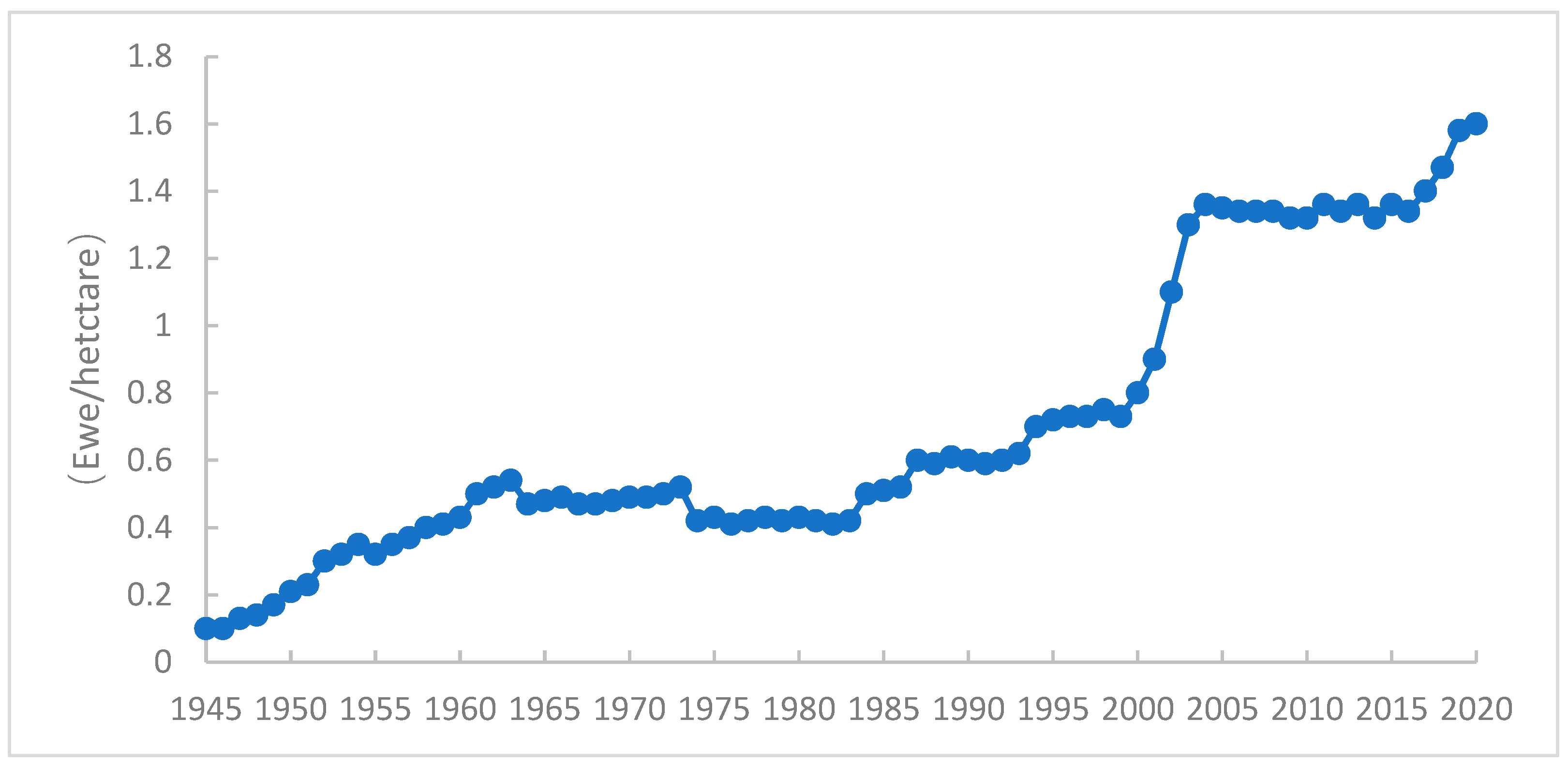

Grasslands play an important role in providing ecosystem services, food security and livelihoods for pastoralists [1,2]. Since the implementation of the grassland ecological compensation policy in 2011, the compensation standard has been improved, the cumulative investment has exceeded 150 billion yuan, which is crucial for herders to enjoy “ecological welfare”, and the comprehensive vegetation coverage of grasslands in China has increased from 51% in 2011 to 56.1% in 2020 [3]. However, the trend of “overall improvement and local deterioration” of the grassland ecological environment has not been fundamentally changed. The actual livestock carrying capacity (the actual number of livestock stocked) in grassland will far exceed the theoretical livestock carrying capacity (the amount of livestock that grassland can carry) (Figure 1), and less than 30% of undegraded grassland will exceed this level by 2030 [4]. Therefore, the manner in which to achieve the effective connection between grassland ecological protection and economic development has become a practical issue that needs to be paid attention to in economic and social development.

Figure 1.

Changes in the stocking capacity of grassland in Inner Mongolia.

As a result, a series of documents on ecological conservation redlines were promulgated and implemented, marking that ecological protection has risen from a regional strategy to a national strategy, which refers to areas with important ecological functions that must be strictly protected. On September 12, 2021, the General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the General Office of the State Council issued the “Opinions on Deepening the Reform of the Ecological Protection Compensation System”, which clearly stated that it is necessary to increase support for areas with a relatively high proportion of ecological protection redlines and optimize the ecological protection redline compensation system [4,5]. Therefore, will the current compensation standard from the central government boost herders’ confidence and enable grassland to recover at an accelerated pace? What are the satisfaction and influencing factors of herders in ecological redline areas? A survey on these questions is of great significance to grassland management, in improving the basic data of Xilin Gol. At present, a large number of studies on grassland ecological compensation mainly focus on the subject and object of compensation [6,7], compensation standards [8], compensation methods [9] and policy implementation effects [10]. As the main stakeholders of grassland ecological protection, the changes in livelihoods and the satisfaction of herders can better reflect the implementation effect of the policy at the micro level. At present, the research is mainly manifested in the following two aspects: on the one hand, the impact of the grassland ecological compensation policy on the actual income of herders is positive [11], especially in the case of the weak supervision of the grassland ecological compensation mechanism; herders with a lower subsidy income level also tend to increase the stoking rate and reduce risks [12,13]. Others believe that the policy has a limited effect on the income of herders [14]. On the face of it, the policy causes the per capita disposable income of herders to be high, but in fact, the production and living costs of herders are extremely high, and the expenditure level of herders under the same conditions is very high; for scattered herders, the infrastructure expenditure such as building houses and sheds in pastoral areas is more than twice as high as that of building houses in rural areas [15]. Vehicle loss and fuel consumption lead to high traffic costs [16]. Herders travel hundreds of kilometers to carry out daily tasks such as sending their children to school or buying daily necessities [17]. However, researchers have demonstrated that ecological compensation has a negative impact on the income level of herders, and the ecological effect is not good [18]. This shows that the level of compensation is insufficient to cover the extra effort expended by herders and does not meet the livelihood expectations of most herders [19], on the other hand, for satisfaction and trust. Some studies appear to show that, compared with herders who do not participate in the policies, herdsmen who enjoy policy dividends differ significantly in their satisfaction with the policies, which is affected by factors such as basic individual characteristics and production characteristics. There are differences in the satisfaction of herders with the policy; the proportions are 29% [20], 57% [21], 69% [22] and 79% [23].

There is rich research on grassland ecological compensation from the single perspectives of policy satisfaction and income level, which provides an important reference basis for the research in this paper. Based on the theoretical framework of the implementation effect of the grassland ecological compensation policy, this paper analyzes the ecological compensation policy with the same theoretical framework as herders in three banner counties with a large area under the control area of the ecological protection redline of Xilin Gol, and uses the field research data to analyze the ecological compensation policy and herdsmen’s income and satisfaction in the same theoretical framework [24,25]. The possible marginal contribution in this paper is as follows. (1) The existing studies on the impact of grassland ecological compensation on herders’ income have not reached a consistent conclusion, and the two dimensions of herdsmen’s income and policy satisfaction are rarely comprehensively depicted to describe the implementation effect of the grassland ecological compensation policy in ecological protection redline areas. (2) Studies have paid insufficient attention to the sustainable livelihood of herders in redline areas, and the question whether herders, as micro-subjects of ecological protection in redline areas, can effectively express and meet their interests and demands is related to the social fairness of the ecological protection redline system. In the process of implementing the ecological protection redline, herders face the problem of restricted land development rights, and the lack of supporting compensation policies reduces the level of welfare. Therefore, through in-depth investigation and empirical analysis, this paper systematically elaborates on the instability of herdsmen’s income, which provides a reference for optimizing the grassland ecological compensation policy, improving the policy efficiency, and enriching the ecological compensation research in the ecological protection redline area.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Analysis and Research Assumptions

It can be seen from the incentive compatibility theory that when the objective functions of the principal and agent are inconsistent, a reasonable incentive mechanism must be used to satisfy both parties. Among environmental policy tools, ecological compensation has the function of regulating income distribution, which can reflect the effect of the policy from the perspective of micro-individuals; that is, satisfaction can reflect the implementation effect of the policy. Eco-compensation has a complex impact on the income of pastoralists with different abilities, and there are different views on poverty alleviation as one of the goals of eco-compensation. However, if it is not considered as a policy tool for poverty reduction, pastoralist participation in policies will be weakened [26,27,28]. However, studies have also shown that participation in eco-compensation programs by low-income herders can increase their income. Based on existing studies [3,27,29], this paper argues that middle- and high-income pastoralists generally have more resources and are very likely to participate in ecological compensation policies. The following hypothesis is therefore proposed:

H1:

Grassland ecological compensation has a positive impact on middle- and high-income herders in ecological protection redline areas.

Income level refers to the income status of herders’ families and the change in herdsmen’s income after participating in the policy. The change in income is an important factor for measuring the willingness and behavior of herders. Some scholars believe that income level and policy satisfaction have a positive impact and that the impact is significant [13]. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2:

The income level has a positive impact on the satisfaction of the ecological compensation policy of herders in the ecological protection redline area.

Reasonable compensation methods are not only an objective requirement for the smooth development of ecological compensation policies, but also one of the key issues in the implementation of ecological compensation systems [30]. According to different compensation methods, such methods can be divided into cash compensation, in-kind compensation, policy compensation and intellectual compensation. Among them, since most herdsmen in reality are risk-averse, cash compensation is the most direct method, which can result in a high level of satisfaction for them. Some studies have also shown a preference for cash compensation over other forms of compensation [31]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3:

Grassland ecological compensation has a positive impact on the policy satisfaction of herders in ecological conservation redline areas.

2.2. Data Sources

Xilin Gol, located in the central part of the Inner Mongolia Plateau, covers approximately 202,600 km2, and the annual precipitation is 200–350 mm. The current permanent population is 1.0426 million. According to the general concepts of “multiple regulations in one” and “a combination of planning and management,” roughly 129,596.42 km2, i.e., 63.97% of Xilin Gol, has been designated as redline areas (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of ECR in various counties.

Inner Mongolia Ecological Conservation Redline Delineation Plan

In September and November 2020, the research team selected three banners with a large proportion of red lines (the Zhenglan Banner Water Source Conservation Ecological Protection Red Line Area, the Sonite Zuo Banner Windbreak and Sand Fixation Ecological Protection Red Line Area, and the East Wuzhumuqin Banner Windbreak and Sand Fixation Ecological Protection Red Line Area) as the research areas for investigation, using the stratified random sampling method. Thirteen gacha were selected in each banner, 15–30 households were selected in each gacha area, a total of 300 questionnaires were distributed, and 270 valid questionnaires were recovered. The efficiency of the questionnaire reached 90%. In order to ensure the authenticity and reliability of the research data, the following principles were followed in the field research: (1) the interviewees who were more familiar with the family situation were preferred; (2) the selected research subjects were all herdsmen who had been engaged in farming since the implementation of the redline policy; moreover, through on-site explanations, the herdsmen had a certain understanding of the research content; and (3) in order to enable the herdsmen to truly express their personal views, we attempted to avoid village cadres in field research to ensure that the herdsmen would not engage in strategic behavior in a real way. At the same time, the research group also held a discussion with the ecological protection redline delineation unit and the Agriculture and Animal Husbandry Bureau (grassland ecological compensation fund distribution unit) to fully understand the implementation of grassland ecological compensation in the ecological protection redline area. In the survey area, the grassland ecological compensation standard given by the central government was 7.5 yuan/mu.

2.3. Variable description

2.3.1. Dependent Variables

The dependent variables studied in this paper include income level and policy satisfaction. Income level was expressed by the average annual household income, policy satisfaction was evaluated according to the effect of the implementation of the grassland ecological compensation policy, and the relevant question designed in the questionnaire was “What is your overall evaluation of the compensation policy in the ecological protection redline area?”.

2.3.2. Core and Control Variables

In the model with the income level of herders, grassland ecological compensation was the core explanatory variable, the basic characteristics of individual herders, family characteristics and regional characteristics are the control variables. According to the existing studies [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19], the basic characteristics of herders include age, education level, participation in technical training, and family characteristics, including family size, self-owned grassland area, and the extent to which they live in cooperatives/family pastures. Regional characteristics include the Zhenglan Flag, Sunite Left Flag, East Wuzhu Muqin Flag. In the model for policy satisfaction, we used grassland ecological compensation, herdsmen’s income, and policy cognition as the core explanatory variables. The individual basic characteristics, family characteristics, cognitive characteristics and regional characteristics of the herders were used as the control variables [17,20]. The cognitive characteristics were expressed according to the understanding of the policy, the impact of the policy, compensation funds, compensation for herdsmen’s losses, and the understanding of government supervision. The rest of the variables were set as above. According to the survey data, 66.71% of the herdsmen were satisfied with the grassland ecological compensation policy, 19.36% of the herdsmen were generally satisfied with the policy, and 13.93% of the herdsmen were dissatisfied with the policy. The descriptive statistics of the variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The descriptive statistics of the variables.

2.4. Research Methods

2.4.1. OLS Regression and Quantile Regression

In order to analyze the impact of grassland ecological compensation on the income of herders in the ecological protection redline area, OLS regression was first carried out (see Equation (1)). However, quantile regression [32,33] can more comprehensively analyze the conditional distribution of the explanatory variables than OLS regression; the regression estimation is therefore more robust, and the quartile (q = 0.25, q = 0.05, q = 0.75, q is divided into points) is used for estimation (see Equation (2)).

Among them, Y is the average annual income of the herders, EC is grassland ecological compensation, is the control variable, is the constant term, is the parameter to be estimated and ε is the random disturbance term.

Among them, represents the factors that have an impact on income, such as the core explanatory and control variables mentioned above. is based on the influencing factors, the value of the income level of the herders at different points. refers to the coefficient by which a variable is divided into points.

2.4.2. Ordered Probit Model

The satisfaction of the herders in the ecological protection redline area with the grassland ecological compensation policy is a multi-categorical ordered variable (dissatisfaction = 0; general = 1; satisfaction = 2), and the independent variables are mostly discrete. The model is therefore as follows [34]:

where * refers to the latent variable; Y^′ refers to the income change variable; T refers to the herders’ perception of the policy; , respectively refers to the influence direction of the three explanatory variables of grassland ecological compensation, herdsmen’s income and herdsmen’s cognition of the policy, CV refers to the control variable, refers to the influence direction of the control variable, ε is the random disturbance term, and the relationship between the latent variable y^* and policy satisfaction (y = 0, y = 1, y = 2) is

Among them, , , is the coefficient to be estimated, and it is .

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. The Impact of Grassland Ecological Compensation on the Income Level of Herders in Ecological Protection Redline Areas

In the analysis of income impact, a multicollinearity test was performed based on the variables selected above. When the variance inflation factor VIF value was closer to 1, the multicollinearity was weaker, and the results show that if the VIF ≤ 2.67, there was no multicollinearity. In this paper, using STATA 16, OLS regression and quantile regression at different quantiles (q = 0.25, q = 0.50, q = 0.75) were carried out to test the robustness of the OLS regression results as well as the difference in income levels at different quantiles. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The influencing factors estimation of grassland ecological compensation on herders’ income.

(1) Grassland ecological compensation. It can be seen from the table that the impact of grassland ecological compensation on the income of the herders was not significant in the OLS regression, and was positive in the quantile regression with q = 0.25, which is consistent with the actual survey. The income from compensation could account for 10% of herdsmen’s income, especially for low-income herders. Moreover, compensation funds were an important source of income, with an income increase effect. The impact on middle- and high-income herders was also not significant, which contradicts the hypothesis H1. The empirical results are consistent with those of Locatelli [35], Wang [36] and other researchers, and inconsistent with those of Ma [37] and Zhu [38], which may be due to the fact that the compensation standards were different in different regions, and the compensation standards were not adjusted after the grassland had been classified as an ecological conservation redline and it had not yet reached the level of incentives for herders to increase income. For middle- and high-income herders, because the opportunity cost of participating in the policy differed greatly from the compensation standard, they were more concerned about whether the delineation of ecological protection redlines would limit their behavior, and low-income herders could obtain a small and important source of income for grassland ecological compensation.

(2) The influence of control variables. In terms of personal characteristics, the age of the herders had a significant negative impact on their income at the level of 10% in the results of regression, and it also passed the significance test at different quantiles. The main reason is that the older the herders were, the lower the possibility of their generating income. Education level and technical training also passed the significance test at different quantiles, which is consistent with the survey situation. Because of the current market force and ecological environment pressure, pastoral production is gradually moving towards industrialization and socialization in the main labor force of pastoral areas. Herders must also have considerable skills and cultural competencies, which is conducive to increasing the income of the herders. In terms of household characteristics, the area of self-owned grassland had a positive impact on the income of the herders at the level of 5%. Moreover, the significance test was passed at the 0.25, 0.50, and 0.75 quantiles; that is to say, herders with a large grassland area, rental or self-use could generate greater income, and the increase in income was more obvious (the same before and after the delineation of the ecological protection redline). For regional characteristics, in the OLS and quantile regression, there was a positive impact; this verifies that compensation had a positive impact on the income of the herders.

3.2. Influencing Factors of Grassland Ecological Compensation Policy Satisfaction in Ecological Protection Redline Areas

According to the previous analysis, STATA 16 was used to perform an ordered Probit model regression, and the grassland ecological compensation amount, income impact and current policy implementation were introduced to measure the influencing factors of herdsmen’s satisfaction with the grassland ecological compensation policy in the ecological protection redline area. In the (1)–(4) regression equation, Prob > chi2 passed the test, indicating that the model fit was good. The results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The estimation of influencing factors on the satisfaction degree of grassland ecological compensation in ecological conservation redline areas.

(1) For the impact of grassland ecological compensation, in Model (1), at the level of 5%, grassland ecological compensation had a positive relationship with herdsmen’s policy satisfaction, and significantly affected policy satisfaction. In Model (2)–(4), it still had a significant positive relationship. The survey also found that the implementation of the policies promoted an increase in herdsmen’s income. Toward this part of the income, herders had a positive attitude.

(2) In terms of income impact, the average annual income of the herders at the level of 1% had a positive impact on policy satisfaction. In models (2)–(4), the results were robust, indicating that herdsmen’s attitude to policy satisfaction was largely related to income changes. For herders as rational economic people, grassland was an important material for animal husbandry production, after the ecological protection redline was delineated. If it could be adjusted to make up for the loss of herdsmen’s income, herders’ satisfaction with the policy was higher, assuming that the results of H2 were confirmed.

(3) In terms of family resource endowment, herders’ participation in technical training had a significant positive relationship with policy satisfaction at the level of 1%, and with the promotion of the modernization process of pastoral areas. The more herders participated in technical training, the more they understood the policy, and the better they could improve the policy satisfaction of the herders. The area of self-owned grassland at the level of 10% had a significant negative relationship with policy satisfaction, especially for the herdsmen with less self-owned grassland, for whom satisfaction with the policy was low. During the survey process, the smallest grassland area for herdsmen was only 80 mu, with each mu of grass and livestock balancing a reward of 3 yuan; such a herdsman only received 240 yuan. Even so, the herders believed that in the delineating ecological protection redline, control was stricter; no matter how high the compensation standard was, they did not not want grassland to be classified into the ecological protection redline area. The extent to which herders participated in cooperatives/family farms had a positive relationship with satisfaction with the policy. Based on this, the herders believed that they could receive the project and the cost was relatively reduced; they were therefore satisfied with the policy.

(4) Policy cognition: Through Model 3, it can be seen that the understanding of grassland ecological compensation policies, the distribution of supplementary reward funds, and the compensation for herdsmen’s losses had a positive relationship with policy satisfaction, while the government’s supervision and herdsmen’s satisfaction with policies had a negative relationship. After the introduction of control variables, such as in Model 4, the positive and negative relationships were still significant, indicating that the results are robust. Possible reasons are: the more they understood the grassland ecological compensation policy, the more willing herders were to participate; compensation funds accounted for 10% of the herders’ income, and the greater the cost of compensation for the loss, the higher the herders’ satisfaction was. Under normal circumstances, local governments supervise herders twice a year, and occasionally there will be “night grazing and over-grazing” phenomena. The higher the willingness of herders to participate in the policy of ecological conservation redline area, the greater the sense of identification with the policy.

4. Discussion

The ecological conservation redline area includes grasslands, forests, wetlands, deserts, etc. Its complex terrain and diverse type gives birth to a unique ecosystem, which has significant heterogeneity in terms of ecological conditions and production methods. It is difficult to obtain robust and effective information. Based on the implementation of the existing grassland ecological compensation policy, this paper discusses the influence of herdsmen’s income and policy cognition, and analyzes policy satisfaction. The empirical results show that the grassland ecological compensation policy has a positive impact on low-income herdsmen, which is consistent with the existing research conclusions [12,13]. Delineating the ecological protection redline is not only to carry out ecological protection. The goal is to keep the redline for a long term. Herdsmen in the ecological conservation redline area have to pay a certain price in order to protect the ecological environment of the grassland [39,40], which has increased the income of herdsmen, but the current effect of grassland ecological protection still has a trend of “partial improvement and overall deterioration”. It is obvious that distributing this ecological compensation fund is necessary. Therefore, after the ecological protection redline is drawn, in order to coordinate ecological protection and economic development, based on the existing compensation, the reconstruction of the grassland ecological compensation mechanism is an important measure to consider carefully [41,42,43]. It is worth pointing out that governments at all levels can concentrate a certain amount of funds to support specific projects and ensure that the interests of residents in the redline area are not damaged. However, pastoralist incomes were found to be precarious in the survey. First, the income of herders fluctuates greatly. For example, 42% households from Xilin Gol returned to poverty owing to drought and sandstorms in 2000. The demand for an animal market in the country affected by the small ruminant disease declined precipitously, and the price of mutton plummeted, resulting in a general sharp decrease in the income of herders in grassland pastoral areas. In particular, many middle- and upper-income herdsmen also returned to poverty. Major disasters also seriously threaten the achievements of poverty alleviation, and if supporting policies are not adopted in the later stage, the people who have been lifted out of poverty face a great danger of returning to poverty collectively. Second, the price of the by-products of animal husbandry falls lower than it is. Due to factors such as the large number of imported products, the rapid development of related substitutes, and weak market demand, the prices of by-products such as skins, casings, fat and wool, which accounted for about 20% of the total income of the animal husbandry industry in the past, have decreased; for example, sheepskin in 2019 was thrown away as garbage even if its price was extremely low. Third, herders have poor adaptability and few ways to increase income. Due to linguistic and cultural differences, pastoralists are weak in occupations other than animal husbandry. Forced by the requirements of grassland ecological environmental protection policies, when herders switch to production or move to a city, their income is greatly reduced. Herdsmen’s poor ability to engage in grassland tourism, health care, vacation, leisure and other industries also affects herdsmen’s conversion to production and their ability to increase their income.

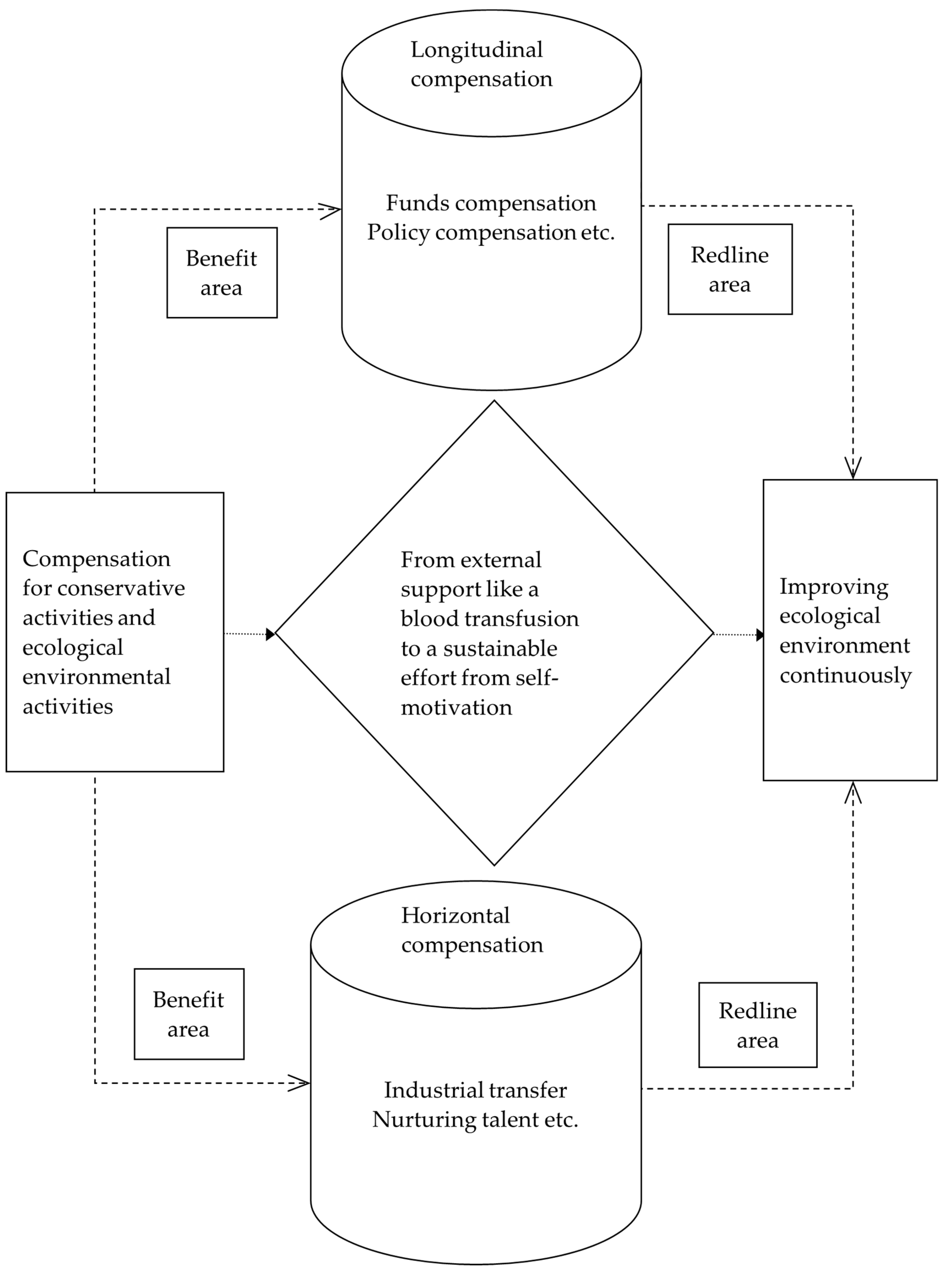

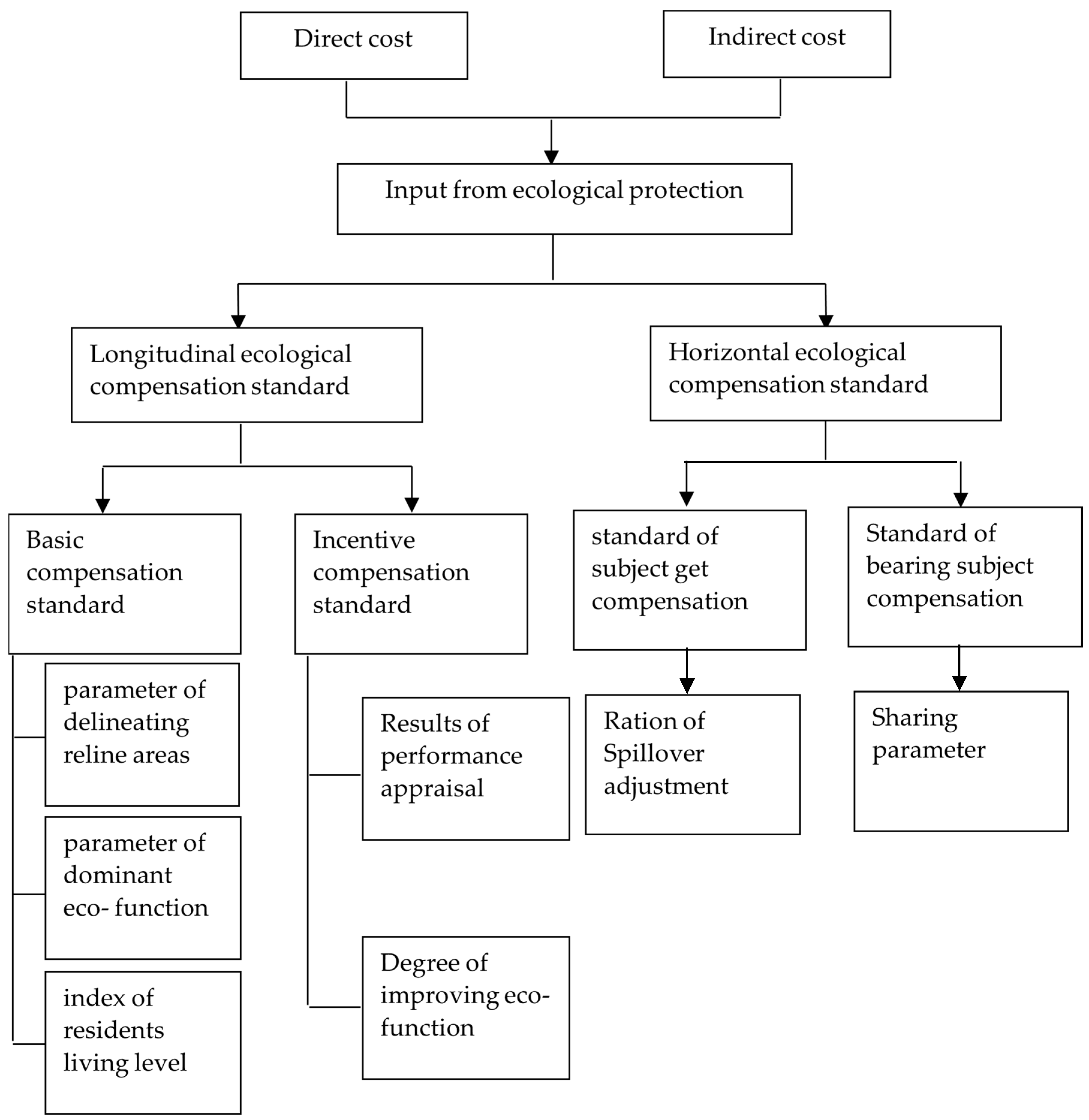

The compensation of ecological protection redline areas has been a challenge in current research. It is necessary to contain longitudinal ecological compensation and horizontal ecological compensation in the source of funds, expanding benefit area and redline area exchanges and cooperation in various fields. The data from Figure 2 and various other data were collected through literature investigation or field investigation, and the accounting methods of ecological compensation standards in important ecological function areas were retrieved. The key links of ecological compensation standards accounting for research on ecological protection redline ecological compensation standards were clearly carried out through the combing of these materials. According to the value of the ecosystem services, two definitions should be established: first, the ecological service value of the ecosystem itself and the actual benefits of the demand side of ecological services; second, the direct and indirect cost of maintaining ecosystem values. Namely, the area of the ecological protection redline area and the dominant ecosystem service function should be considered important factors for the transfer payment of the ecological protection redline area. This is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

The source of compensation funds.

Figure 3.

Technological roadmap of ecological conservation redline compensation standard.

Although our actual research resulted in some interesting findings, it is undeniable that there are still some limitations. Conflict in the redline areas, including ecological problems and poverty, is very prominent, and the dependence on resources is more obvious [44,45]. According to the theory of relative deprivation, once the individual compares his situation with others in the group, and he is at a disadvantage, a sense of relative deprivation will arise [46,47], called the “sense of deprivation.” Moreover, a “sense of unfairness” is actually a hidden problem that cannot be ignored in the process of promoting ecological protection ecological policies, especially when there are obvious differences in ecological policies inside and outside the redline area. Residents’ sense of survival and development is unbalanced, and therefore herdsmen’s satisfaction perception of the implementation effect of the grassland ecological compensation policy will lead to different perception results due to individual differences and regional differences, and there may be certain deviations which will also affect the implementation effect of the policy [48].

As a micro-subject, herders play an important role in balancing economic development and ecological protection in the process of the delineation and implementation of ecological protection redlines. However, due to the large scope of ecological protection redlines and wide areas, there are certain difficulties in obtaining relevant data, which is also the author’s next research goal. Based on existing literature [49,50,51,52], empirical analysis, and field research, through interviewing experts who have been working in pastoral areas for a long time, it is currently possible to determine that the ecological protection red line is drawn, strictly speaking, and the practice of relying on quantitative animal husbandry to increase income has become a thing of the past. There is an urgent need to explore ways to increase income from animal husbandry products. One way is to develop green livestock products, to give full play to the advantages of pure natural, pollution-free and green products in grassland animal husbandry areas, to further promote the certification, publicity, protection, technological development and other work on green livestock products, and to strive to create high-value livestock products. The second is to rely on science and technology to increase individual production, to continue to promote livestock improvement, and to strengthen the selection and breeding of fine varieties. The third is to strengthen animal disease prevention and control technology. With the delineation of the red line of ecological protection, the proportion of animal husbandry in barnyards will increase. It is necessary to comprehensively improve the veterinary team and improve the safety monitoring capabilities of animal products. First, we must implement a long-term financial support policy. In view of the long-term existence of income reduction, as well as weak production implementation and a poor financing environment in pastoral areas during the process of herdsmen changing production, it is recommended that a long-term subsidy policy for herdsmen be implemented. The fourth method is to implement an incremental mechanism for supplementary reward standards. It is suggested that the reward and subsidy standard be further increased, among which the subsidy for grazing prohibition would be increased to about 30 yuan per mu, and the reward for grass–livestock balance would be more than 8 yuan per mu. The fifth method is to expand the scope of reward and subsidy, and to compensate to a certain extent for a series of chain reactions, marginalized impacts, and losses brought about by the delineation of ecological protection red lines, including subsidies for additional production implementation, compensation for epidemic losses, living in cities, training and employment, and other aspects. The sixth method is to promote the scientific detection of grassland productivity and the dynamic balance of grassland and livestock, by establishing a grassland productivity detection system based on satellite monitoring, remote sensing monitoring, big data technology and field sampling inspections, and striving to achieve a refined dynamic balance of grass and livestock based on the herdsman and scientifically setting the balance point of each herdsman’s grass and livestock balance. The seventh method is to improve the laws and regulations on the protection of grasslands in the ecological protection redline area, by legislating and formulating laws and regulations to charge fees for activities that destroy grassland production in redline areas, including collecting grassland ecological environment protection fees for mining, dust pollution, the erection of high-voltage line passages, road construction, grassland tourism and green hay transportation.

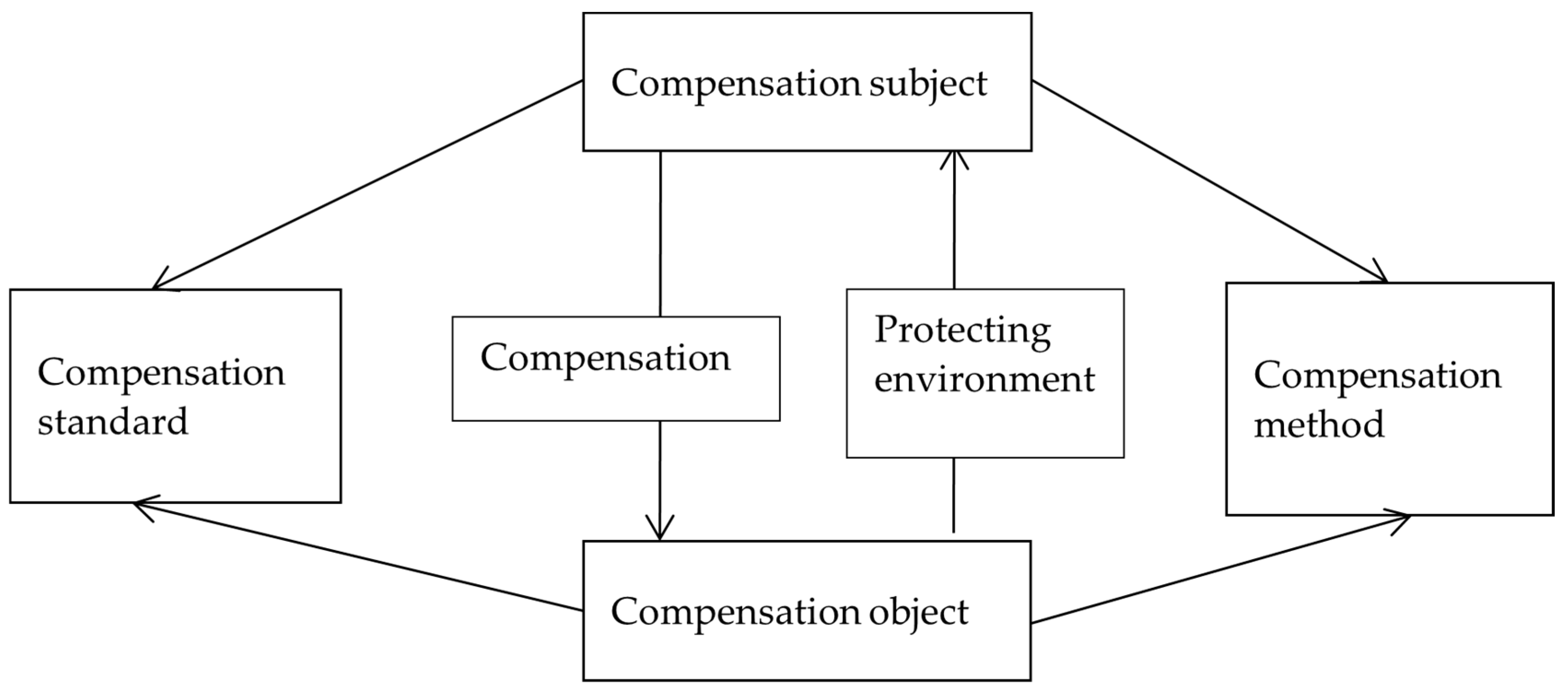

Based on first-hand data, we collected people’s views and insights on the delineation of the ecological protection redline and the current understanding of grassland ecological compensation in redline areas. However, the ecological protection redline was just delineated, and the rigid ecological policy constraints still lack the refined consideration of farmers’ livelihoods, and the protected areas overlap with farmers’ production and living areas. A series of challenges such as deviations from implementation goals and results, as well as a lack of implementation exist. Whether as factor compensation and regional compensation at the national level, or the local practice of ecological compensation, they all focus on improving the basic public service guarantee capacity of the government in ecological protection redline areas, and do not formally incorporate ecological protection redline factors in standard measurement and allocation [53]. Therefore, on the one hand, the key elements such as compensation subject, compensation object, compensation standard, compensation method, supervision and management should be analyzed in the redline area (Figure 4), and on the other hand, big data based on ecological monitoring at the macro level, economic and social statistics of pastoral areas, and livelihood data of farmers and herdsmen at the micro level can also be used for follow-up studies, by mutual confirmation and supplementation of data at different levels. We fully evaluate the implementation effect of the policy.

Figure 4.

The key elements of the compensation mechanism in the redline area.

5. Conclusions

Based on the above analysis, the following conclusions can be drawn:

(1) Grassland ecological compensation showed a significant positive impact on low-income herders in ecological protection redline areas. Grassland ecological compensation, income impact and the current policy implementation have a positive impact on policy satisfaction.

(2) Herdsmen’s overall satisfaction with the grassland ecological compensation policy is high, and after the ecological protection redline is delineated, the practice of relying on quantity to increase animal husbandry income passed. It is also urgent to explore the increase in livestock product income.

(3) Age showed a negative impact on income level, and free grassland area had a positive impact on income level. Technical training and participation in cooperatives/family farms had a positive impact on policy intention, while grassland area had a negative impact on them.

To sum up, there are the following policy suggestions: (1) Guarding the red line and ensuring the ecological security of grasslands in carrying out grassland ecological compensation in ecological protection redline areas, increasing support for areas with a high proportion of ecological protection redline coverage, and at the same time, raising herdsmen’s awareness of compensation and management inside and outside the redline area. (2) Strengthening incentives to improve the well-being of herders. Before the smooth implementation of the policy, based on the herdsmen’s willingness to be compensated, and with reference to the ecological service functions led by the ecological protection redline area, the value guidance compensation standard is measured, and the employment and income of herders are increased under the premise of ensuring that the ecological functions are not reduced. (3) Hardening constraints and strengthening the monitoring of grassland ecological conditions. Grassland management and protection is mainly based on patrol methods, supervision and monitoring measures are still mainly “people watching, seeing”, and focus on controlling the number of livestock. Grassland management and monitoring work lacks modern supervision and monitoring methods. In the future, it will be necessary to strengthen the dynamic monitoring of redline areas in various dimensions to make supervision more targeted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Y. and G.Q.; methodology, L.Y.; software, L.Y.; validation, L.Y. and G.Q.; formal analysis, L.Y.; investigation, L.Y.; resources, G.Q.; data curation, L.Y. and G.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Y.; writing—review and editing, G.Q.; supervision, G.Q.; project administration, G.Q.; funding acquisition, G.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China (20BGL165) as well as the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71963027).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jiang, B.; Chen, Y.; Bai, Y.; Xu, X. Supply–Demand Coupling Mechanisms for Policy Design. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, X.; Jing, Y.; Cai, E.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Spatial Patterns and Driving Forces of Conflicts among the Three Land Management Red Lines in China: A Case Study of the Wuhan Urban Development Area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The New Beijing News. The Grassland Ecological Subsidy Policy Has Been Implemented for 10 Years, Benefiting More Than 12 Million Farmers and Herdsmen [EB/OL]. (2021-12-03); The New Beijing News: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- General Office of The CPC Central Committee. General Office of The State Council. Some opinions on delimiting and strictly observing the red line of ecological protection. Gaz. State Counc. People’s Repub. China 2017, 7, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- General Office of The CPC Central Committee. General Office of The State Council. Some opinions on deepening the reform of ecological compensation system. The People’s Daily 2021, 9, 12. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-09/12/content_5636905.htm (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Qiu, S.L.; Jin, L.S. Eco-Compensation in ecological protection redline area: Practice progress and experience enlightenment. Reform Econ. Syst. 2021, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Qiao, G.H. On the ecological compensation standard for herders’ willingness to accept in grassland ecological conservation redline area. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2021, 35, 5560. [Google Scholar]

- Bórawski, P.; Bełdycka-Bórawska, A.; Szymanska, E.J.; Jankowski, K.J.; Dunn, J.W. Price volatility of agricultural land in Poland in the context of the Euro⁃pean Union. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.N.; Huang, J.; Hou, L.L. Impacts of the Grassland Ecological Compensation Policy on Household Livestock Production in China: An Empirical Study in Inner Mongolia. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 161, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.L.; Xia, F.; Chen, Q. Grassland Ecological Compensation Policy in China Improves Grassland Quality and Increases Herders’ Income. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Hou, Y.; Langford, C.; Bai, H.; Hou, X. Herder stocking rate and household income under the Grassland Ecological Protection Award Policy in northern China. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Dries, L.; Huang, J.K.; Min, S.; Tang, J.J. The impacts of the eco-environmental policy on grassland degradation and livestock production in Inner Mongolia, China: An empirical analysis based on the simultaneous equation model. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waylen, K.A.; Martin-Ortega, J. Surveying Views on Payments for Ecosystem Services: Implications for Environmental Management and Research. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 29, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Yu, Z.; Xu, B. The causes of formation and the outlets of the three dimensional issues of animal husbandry, herdsman and pastoral area: Simultaneously discussion on the integration of grass resources in China. Issues Agric. Econ. 2009, 30, 78–88+112. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, N.T.; Galvin, K.A.; Stokes, C.J. Fragmentation of rangelands: Implications for humans, animals, and landscapes. Glob. Environ. Change 2008, 18, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, M.; Li, W. Market-based grazing land transfer and customary institutions in the management of rangelands: Two cases studies on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 287–295. [Google Scholar]

- Börner, J.; Baylis, K.; Corbera, E.; Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Honey-Rosés, J.; Persson, U.; Wunder, S. The Effectiveness of Payments for Environmental Services. World Dev. 2017, 96, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Brown, C.; Qiao, G.; Zhang, B. Effect of eco-compensation schemes on household income structures and herder satisfaction: Lessons from the grassland ecosystem subsidy and award scheme in Inner Mongolia. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; He, C.X.; Zh, X. Implementation effects of grassland ecological compensation and awarding policy--Based on the production subsidy. Pratacultural Sci. 2015, 32, 287–293. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.T.; Liu, D.; Jin, L.S. Grassland Eco-compensation: Ecological Performance, Income Effect and Policy Satisfaction. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2016, 26, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.X.; Wei, T.Y.; Jin, L.S. Herds people Attitudes Towards Grassland Eco-Compensation Policies in Siziwang Banner, Inner Mongolia. Resour. Sci. 2014, 36, 2442–2450. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, B.; Ma, R.Y.; Qiao, G.H. Grassland Ecological Reward Policy: Research on the Formation Mechanism of High Satisfaction but Low Execution. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2015, 6, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Nan, Z.B.; Chen, Q.Q.; Tang, Z. Satisfaction and influencing factor to grassland eco-compensation and reward policies for herders: Empirical study in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and western desert area of Gansu. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 1436–1444. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerville, M.; Jones, J.P.G.; Rahajaharison, M.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. The role of fairness and benefit distribution in community- based payment for environmental services interventions: A case study from Menabe, Madagascar. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1262–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alix-Garcia, J.M.; Sims, K.R.; Yanez-Pagans, P. Only one tree from each seed: Environmental effectiveness and poverty alleviation in Mexico’s payments for ecosystem services program. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2015, 7, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenkor, R.R.; Bassett, G.W. Regression quantiles. Econometrica 1978, 46, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Nan, Z.B.; Tang, Z. Influencing factors of the grassland ecological compensation policy to herdsmen’s behavioral response: An empirical study in Hexi corridor. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagiola, S.; Arcenas, A.; Platais, G. Can payments for environmental services help reduce poverty? An exploration of the issues and the evidence to date from Latin America. World Dev. 2005, 33, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemkes, R.J.; Farley, J.; Koliba, C.J. Determining when payments are an effective policy approach to ecosystem service provision. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2069–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landell-mills, N.; Porras, I.T. Silver bullet or fools’ gold: A global review of markets for forest environmental services and their impact on the poor. Lond. Int. Inst. Environ. Dev. 2002, 100, 173. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, J.; Chu, Z.L.; Jin, L.S. Willingness of compensation for resource heterogeneous farmers returning farmland to forests and its influencing factors. Rural Economy 2020, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.J.; Xie, B.G.; Li, X.Q.; Liao, H.Y.; Wang, J.Y. Ecological compensation standards and compensation methods of public welfare forest protected area. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 27, 1893–1900. [Google Scholar]

- Obeng, E.A.; Aguila, R.F.X. Value orientation and payment for ecosystem services: Perceived detrimental consequences lead to willingness-to-pay for ecosystem services. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 206, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.H.; Zhao, M.J.; Liu, J.M.; Zhang, D.-J. Research on the basic farmland distribution in mountainous areas based on ecological harmony and construction suitability. J. Nat. Resour. 2018, 33, 2167–2182. [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli, B.; Rojas, V.; Salinas, Z. Impacts of payments for environmental services on local development in northern Costa Rica: A fuzzy multi-criteria analysis. For. Policy Econ. 2008, 10, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Poe, G.L.; Wolf, S.A. Payments for ecosystem services and wealth distribution. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 132, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Gao, J.Z. Forest ecological compensation, income impact and policy satisfaction. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.F.; Yin, H.D.; Zhang, Z.T.; Ke, S.F. Does ecological compensation benefit poverty alleviation: Taking three gorges ecological barrier construction area as an example. J. Northwest AF Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 18, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Jiang, B.; Wang, M.; Li, H.; Alatalo, J.M.; Huang, S.F. New ecological redline policy (ERP) to secure ecosystem services in China. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunting, F.; Ming, C.; Wei, W.; Hao, W.; Liu, F.Z.; Zhang, L.B.; Du, J.H.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, W.J.; Li, J.S. Which management measures lead to better performance of China’s protected areas in reducing forest loss? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 142895. [Google Scholar]

- Imaran, K.; Minjuan, Z.; Sufyan, U.; Liuyang, Y.; Arif, U.; Tao, X. Spatial heterogeneity of preferences for improvements in river basin ecosystem services and its validity for benefit transfer. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 627–637. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.J.; Peng, H.; Xia, H.; Chen, X.M.; Zhang, W.S. Study on total pollutant Control in middle-lower Hanjiang River Based on environment quality baseline. Yangtze River 2020, 51, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, S.W.; Zhang, J. Can Xin’anjiang River Basin horizontal ecological compensation reduce the intensity of water pollution? China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2018, 28, 152–159. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.F.; Li, G.P.; Han, X.P. Conflict between famers’ ecological protection and development intention in nature reserve: Based on the research data of 660 households of famers around the national nature reserve in Shaanxi. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2015, 25, 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- An, L.; Lupi, F.; Liu, J.; Linderman, M.A.; Huang, J. Modeling the choice to switch from fuelwood to electricity: Implications for giant panda habitat conservation. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 42, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runciman, W.G. Relative deprivation and social justice: A study of attitudes to social inequality in twentieth-century England. Br. J. Sociol. 1966, 17, 430–434. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H. Spatial inequality of China’s environmental pollution control investment: Based on theory of relative deprivation. J. Technol. Econ. 2019, 38, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.D.; Chen, H.B. Facilitation or hindrance: How to grassland ecological subsidies affect herdsmen’s propensity to lease pastures? J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2022, 36, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Wunder, S.; Ruiz-Pérez, M.; Moreno-Sanchez, R. Global Patterns in the Implementation of Payments for Environmental Services. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.X.; Yeh, E.; Tan, S. Marketization Induced Overgrazing: The Political Ecology of Neoliberal Pastoral Policies in Inner Mongolia. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 86, 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- Naess, M.W.; Bardsen, B.J. Market Economy vs. Risk Management: How Do Nomadic Pastoralists Respond to Increasing Meat Prices? Hum. Ecol. 2015, 43, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.H.; Wen, Y.H. Thoughts of compensation mechanism based on the ecological protection redlines. Environ. Prot. 2017, 45, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.; Wang, X.Y.; Yang, M.F.; Cai, J.Z. Application of ecosystem services research on a protection effectiveness evaluation of the ecological redline policy. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 3365–3371. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).