Methodology for the Study of the Vulnerability of Historic Buildings: The Reconstruction of the Transformation Phases of the Church of the Abbey-Castle of Santo Stefano in Monopoli in Puglia (Italy)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

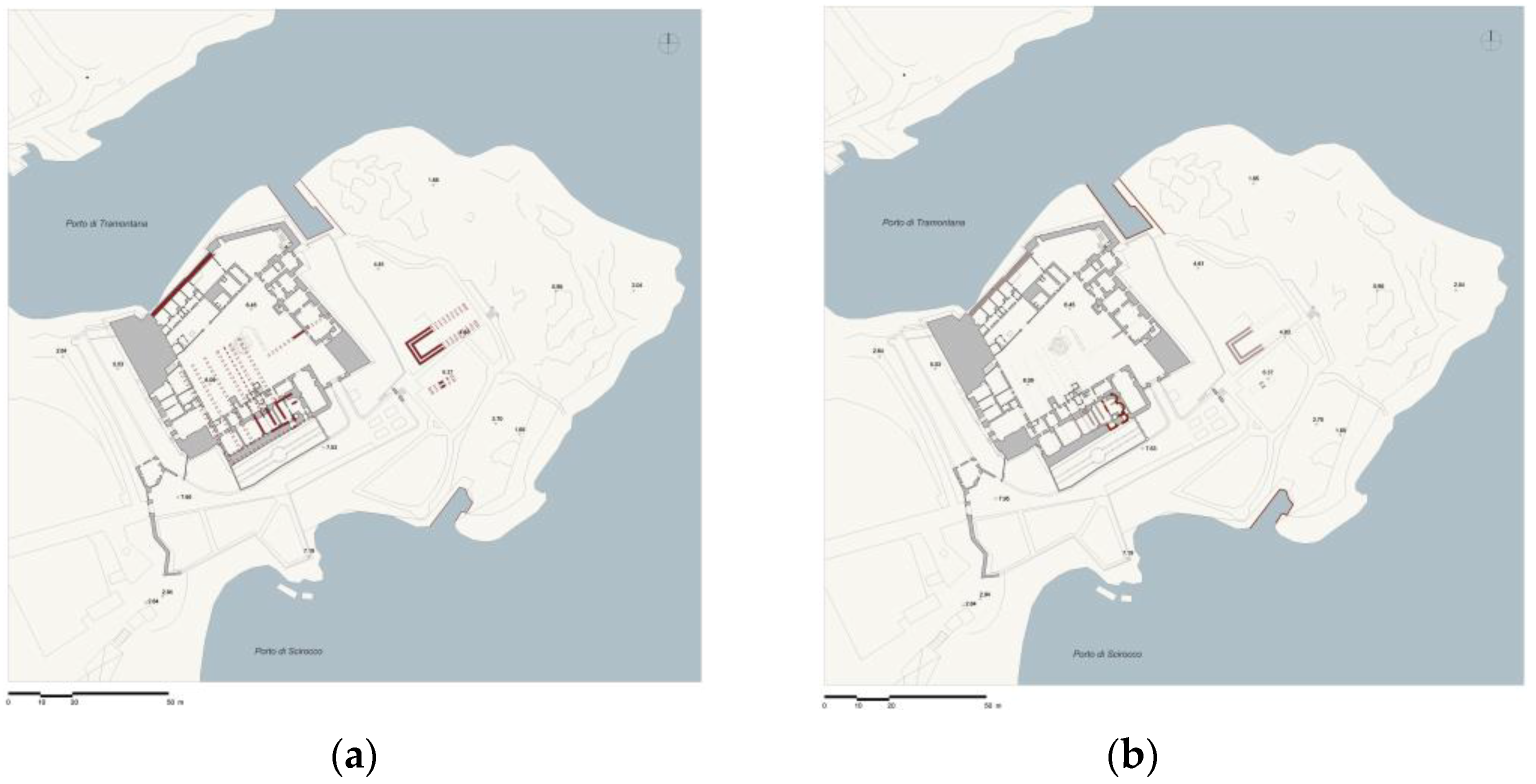

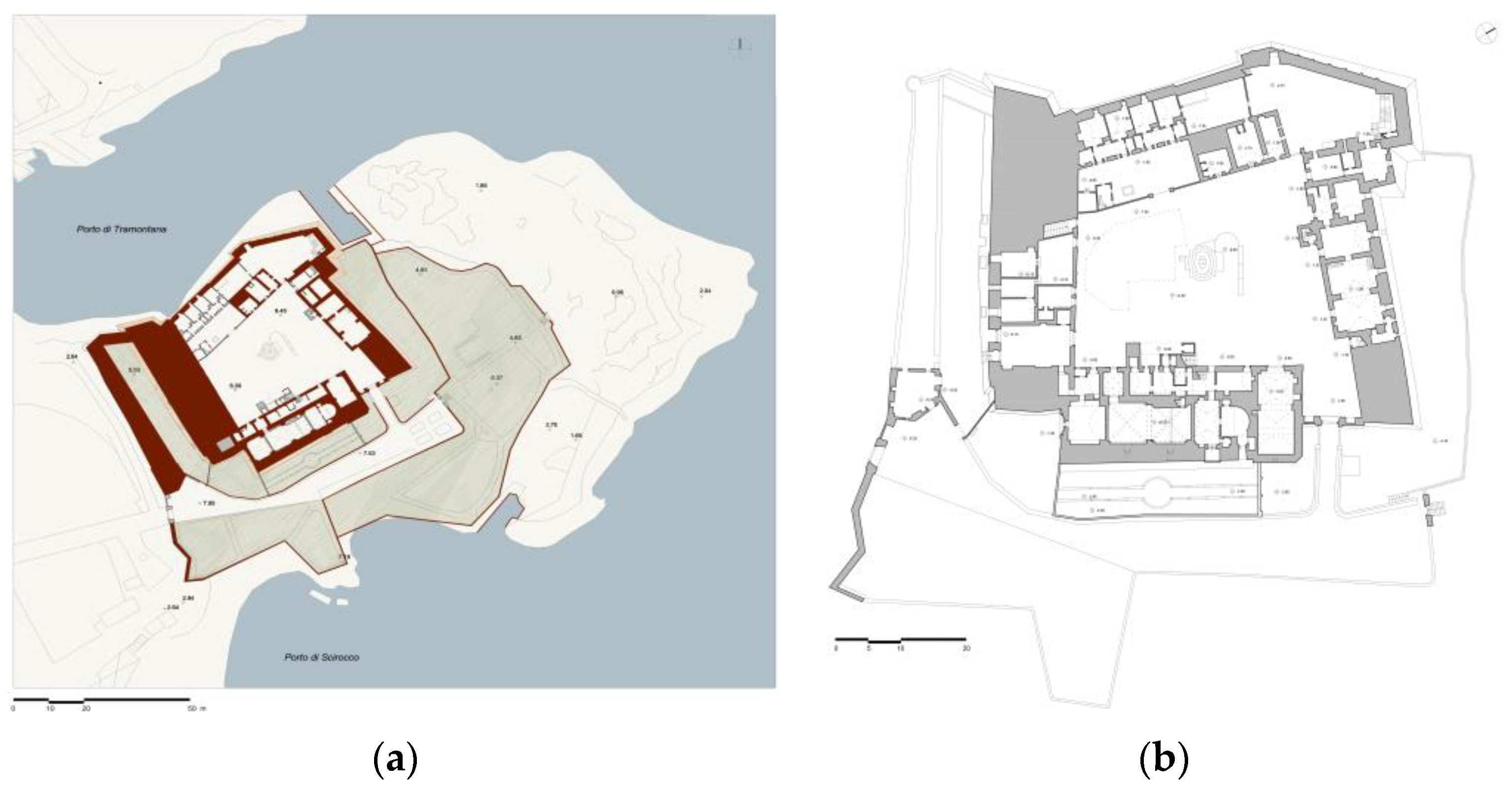

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

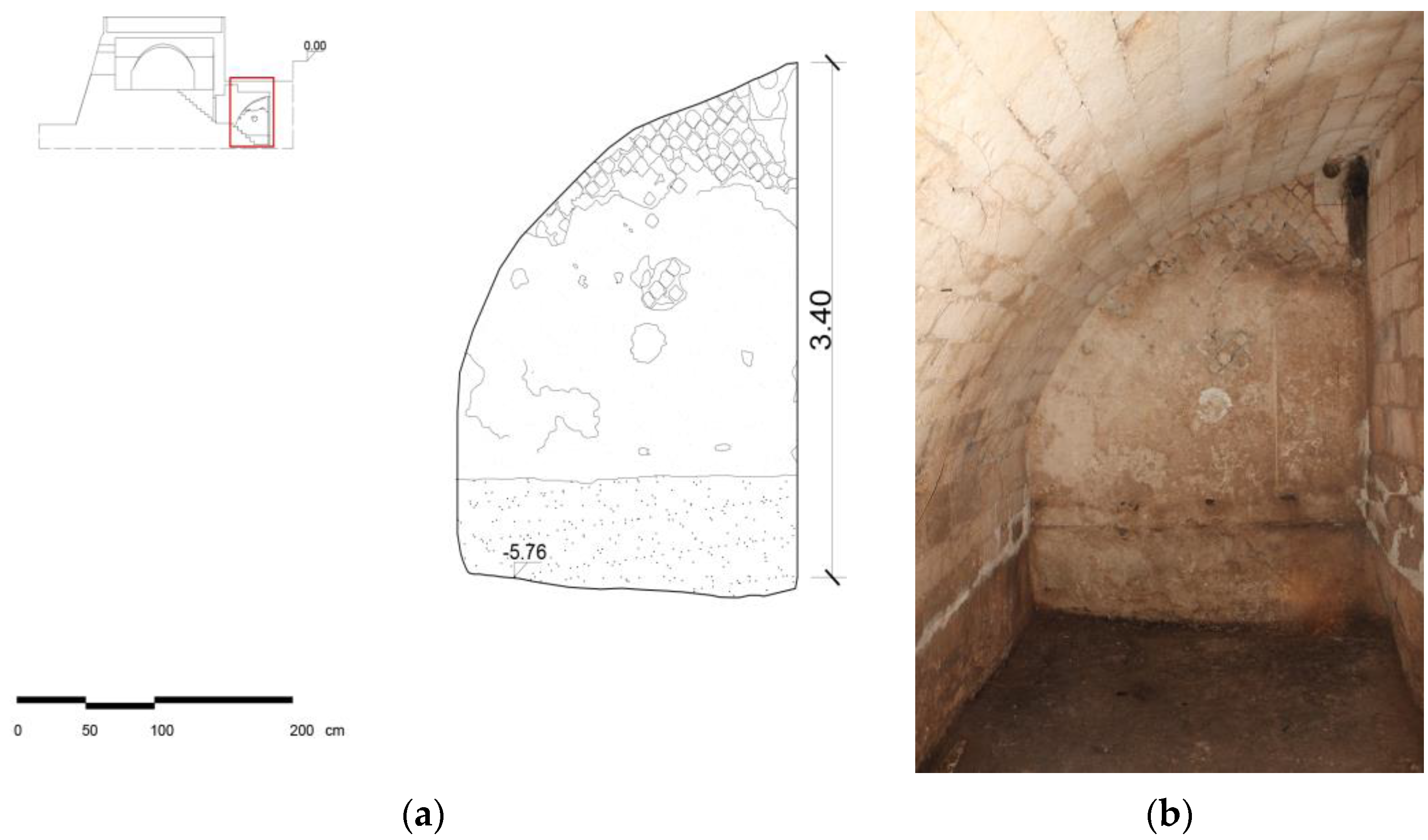

3.1. Analysis of the Underground Rooms of the Church

3.2. Analysis of the Vulnerability of Underground Environments

3.2.1. The Plasters

3.2.2. The Degradation

3.2.3. The Comparison

3.2.4. Stratigraphic Investigations

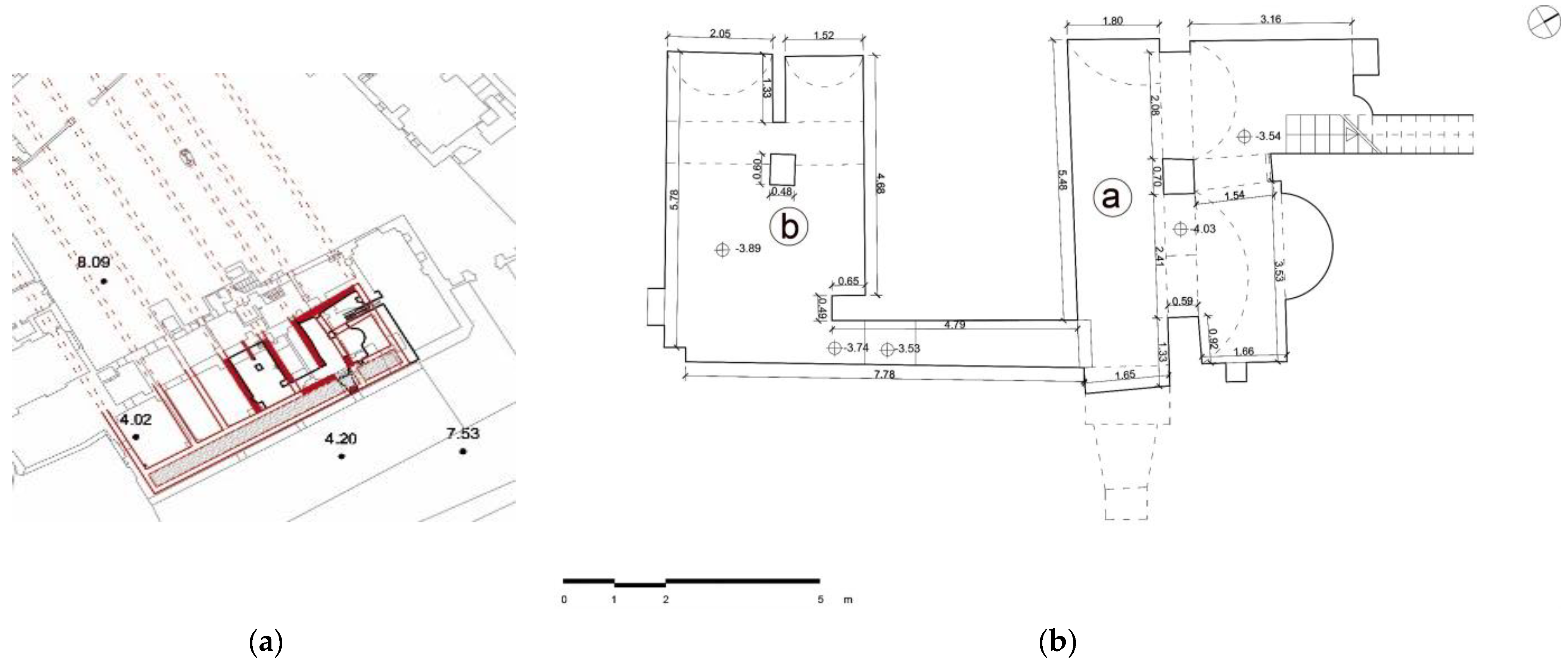

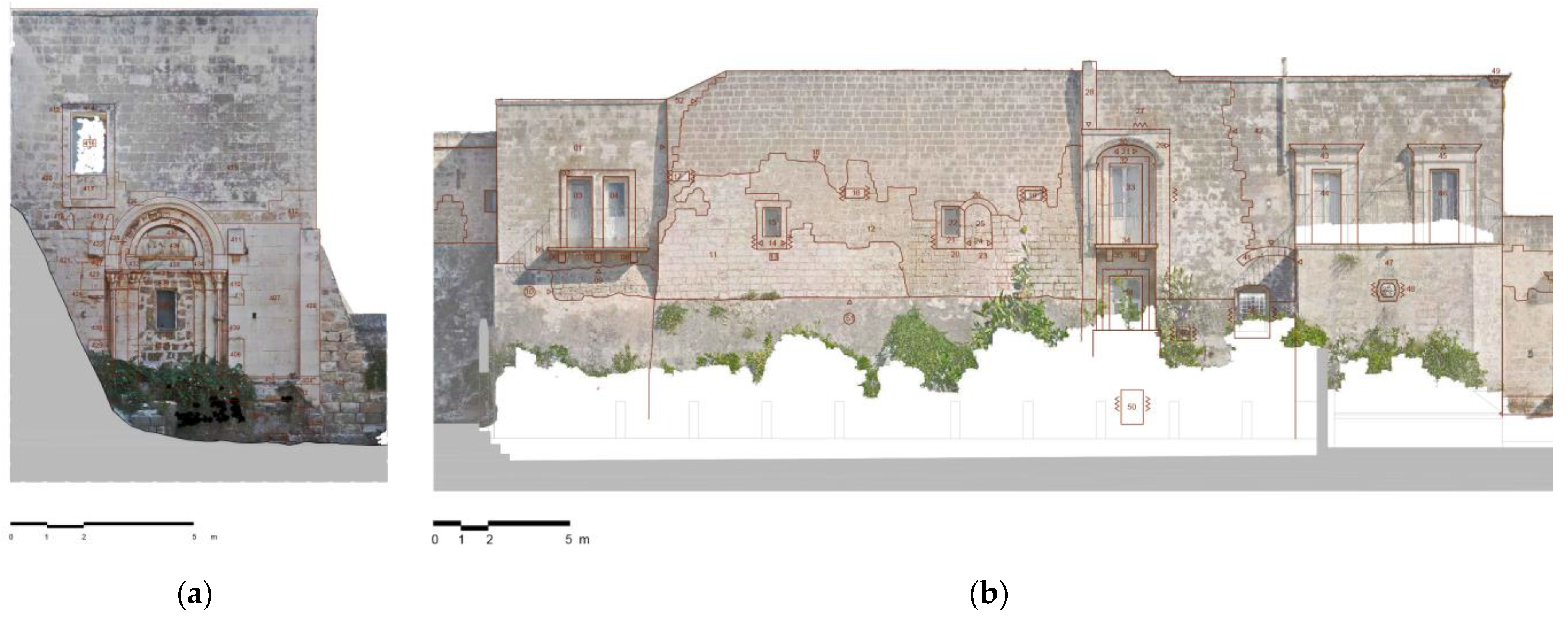

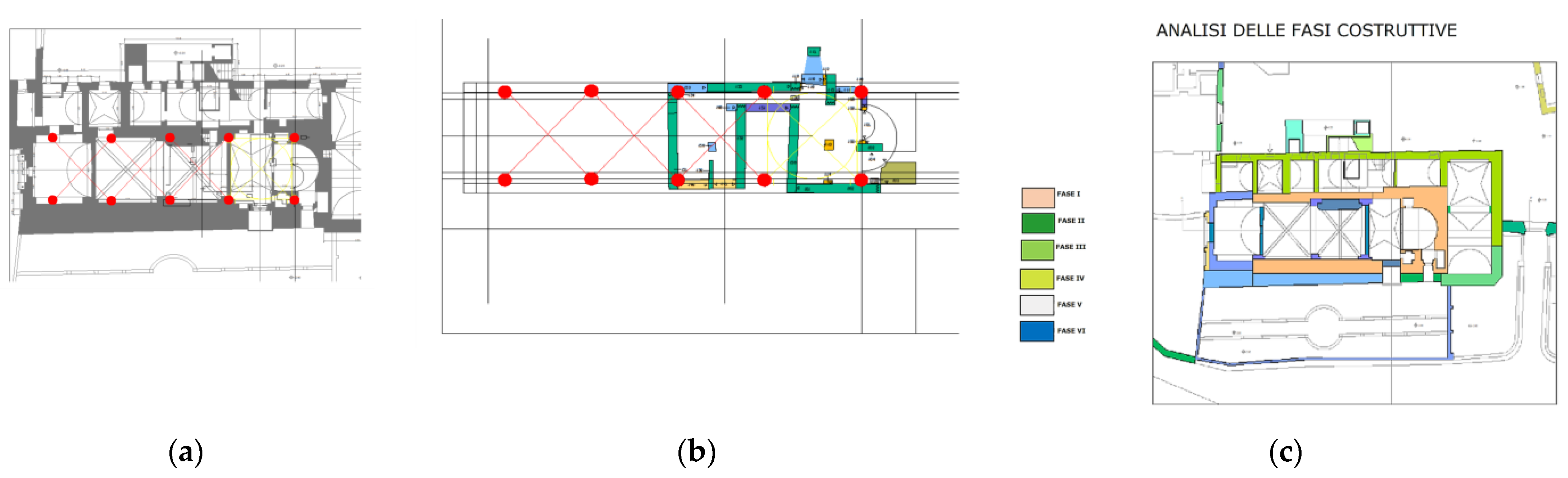

4. Analysis of the Church Blockade

4.1. Vulnerability Analysis of the Church Blockade

4.1.1. Thermographic Pre-Diagnosis

4.1.2. Comparison

4.1.3. The Brindisi Earthquake

4.1.4. The Stratigraphic Survey

4.1.5. The Church Today

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Conservazione Preventiva. Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/it/section/conservazione-preventiva (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Diceglie, A.; D’Amico, N. Preservation and rehabilitation of historic buildings and structures: Case studies. The restoration site of an house in Monopoli Largo Castello, N. 5. In Proceedings of the REHAB 2017 3rd International Conference on Preservation, Maintenance an Rehabilitation of Historical Buildings and Structures, Braga, Portugal, 14–16 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cagnana, A. Archeology of Building Materials; Publisher: Mantua, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amelio, M.G.; Esposito, D. The Dismantling Site: The ‘Stony Ground’ along the Via Flaminia. Observations on the Recovery of Building Materials. In On the Via Flaminia, The Mausoleum of Marco Nonio Ma-Crino; Rossi, D., Ed.; Electa: Milan, Italy, 2012; pp. 331–343. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, J.-F.; Bernardi, P.; Esposito, D. Reuse in Architecture: Recovery, Transformation, Use; Collection de l’École Française de Rome, 418: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Diceglie, A. Problems of conservation of archaeological structures subject to variations in humidity. The Case Study of the Castle of Santo Stefano. In Proceedings of the First International Scientific Conference “The Colors of Restoration”; Nardini Editore: Florence, Italy, 2021; pp. 475–489. [Google Scholar]

- Diceglie, A. The Castle of Santo Stefano in Monopoli in Puglia; Archeology for Architecture; Gangemi: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Egnazia. Available online: https://www.progettomusas.eu/arch_site/egnazia/ (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Diceglie, A. Cit. 2018. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/28570572/Tecniche_edilizie_nel_mondo_antico (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- The Aerofotografico Center Laboratory Consortium of the University of Bari Aldo Moro Operational from 2000 to 2015 Mainly Dealt with Aerial Prospecting, Remote Sensing Surveys, Thermographic and Geophysical Surveys for the Knowledge of Urban Centers of Historical Artifacts and Archaeological Areas.

- Bianchini, M. Building Techniques in the Ancient World, Rome. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, N. Naples, State Archives, General Administration of the Amortization Fund and Public Property, Malta-Putignano-Cabreo di S. Stefano, b. 3540, f. 164, 1675, ff. 3v–4v. In Monumental Testimonies and Settlement Policy of the Bailiffs of Santo Stefano in the Light of Relations with Rhodes and Malta. Ph.D. Thesis, History of Comparative Art, Civilizations and Cultures of Mediterranean Countries, XXIV Cycle, University of Bari ‘Aldo Moro’, Bari, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Seymaour, L.M.; Maragagh, J.; Sabatini, P.; Di Tommaso, M.; Weaver, J.C.; Masic, A. Hot mixing: Mechanistic insights into the durability of ancient Roman concrete. J. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadd1602. [Google Scholar]

- Calò, M.M.S. Two Cathedrals in Molise: Termoli and Larino, Rome 1979; EAD, San Leonardo di Siponto «iuxta stratam peregrinorum», Galatina 2013 (Small Monographs of Puglia); EAD, Monte Sant’Angelo. The Monumental Complex of San Pietro, Santa Maria Maggiore and the Baptistery of San Giovanni, Galatina 2013 (Small Monographs of Puglia). 2013. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, N. Valletta, National Library, AOM 6002, f. 11v, Summary of the Restorations of the Balì Francone in Santo Stefano. In Monumental Testimonies and Settlement Policy of the Balì of Santo Stefano in the Light of Relations with Rhodes and Malta. Ph.D. Thesis, History of Art Comparative, Civilizations and Cultures of Mediterranean Countries, XXIV Cycle, University of Bari ‘Aldo Moro’, Bari, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ASB (State Archives of Bari). Fll. 48–53 Cabreo di Santo Stefano from 1777; ASB: Bari, Italy, 1777. [Google Scholar]

- ASB (State Archives of Bari). Intendenza di Terra di Bari, State Property, ‘Comparative Status of the Assets and Income Described in the Cabreo del Baliaggio di Fasano under the Title of St. Stephen of the Year 1777 for Notar D. Andrea Zac-caria of Ostuni’, B. 29, Fasc. 431; ASB: Bari, Italy, 1777. [Google Scholar]

- AA. VV. The stratigraphic analysis of the elevated: Contributions to the knowledge of fortified architecture and to the restoration project, supplement of Medieval Archaeology, All’ insignia of Giglio Florence 2006. In Proceedings of the 11th Congress of Archeology of Architecture of Udine 2006, Udine, Italy, 10–11 November 2006; Quendolo, A., Ed.; Giglio: Florence, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://ingvterremoti.com/2020/08/17/la-sismicita-storica-del-salento-il-forte-tremoto-del-20-febebruary-del-1743/ (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Carocci, C.; Macca, V. Buildings’ masonry work: Construction quality and seismic damage after 2016 Italy earthquake. In Proceedings of the HERITAGE 2020—7th International Conference on Heritage and Sustainable Development, Coimbra, Portugal, 8–10 July 2020; Amoêda, R., Lira, S., Pinheiro, C., Eds.; pp. 481–490. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diceglie, A. Methodology for the Study of the Vulnerability of Historic Buildings: The Reconstruction of the Transformation Phases of the Church of the Abbey-Castle of Santo Stefano in Monopoli in Puglia (Italy). Sustainability 2023, 15, 1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021702

Diceglie A. Methodology for the Study of the Vulnerability of Historic Buildings: The Reconstruction of the Transformation Phases of the Church of the Abbey-Castle of Santo Stefano in Monopoli in Puglia (Italy). Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021702

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiceglie, Angela. 2023. "Methodology for the Study of the Vulnerability of Historic Buildings: The Reconstruction of the Transformation Phases of the Church of the Abbey-Castle of Santo Stefano in Monopoli in Puglia (Italy)" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021702

APA StyleDiceglie, A. (2023). Methodology for the Study of the Vulnerability of Historic Buildings: The Reconstruction of the Transformation Phases of the Church of the Abbey-Castle of Santo Stefano in Monopoli in Puglia (Italy). Sustainability, 15(2), 1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021702