The Future of Agriculture: Obstacles and Improvement Measures for Chinese Cooperatives to Achieve Sustainable Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. History and Development of Policies on Cooperatives

2.1. Emerging Stage (2007–2012)

2.2. Diversified Expansion Stage (2013–2017)

2.3. Quality Improvement and Efficiency Enhancement Stage (2018 to Present)

2.3.1. Improvement of Regulatory System

2.3.2. Strengthening the Model Effect of Pilot Demonstrations

2.3.3. Promoting Standard Registration

3. Present Situation of Sustainable Development of Chinese Cooperatives

3.1. Specific Characteristics of Chinese Cooperatives

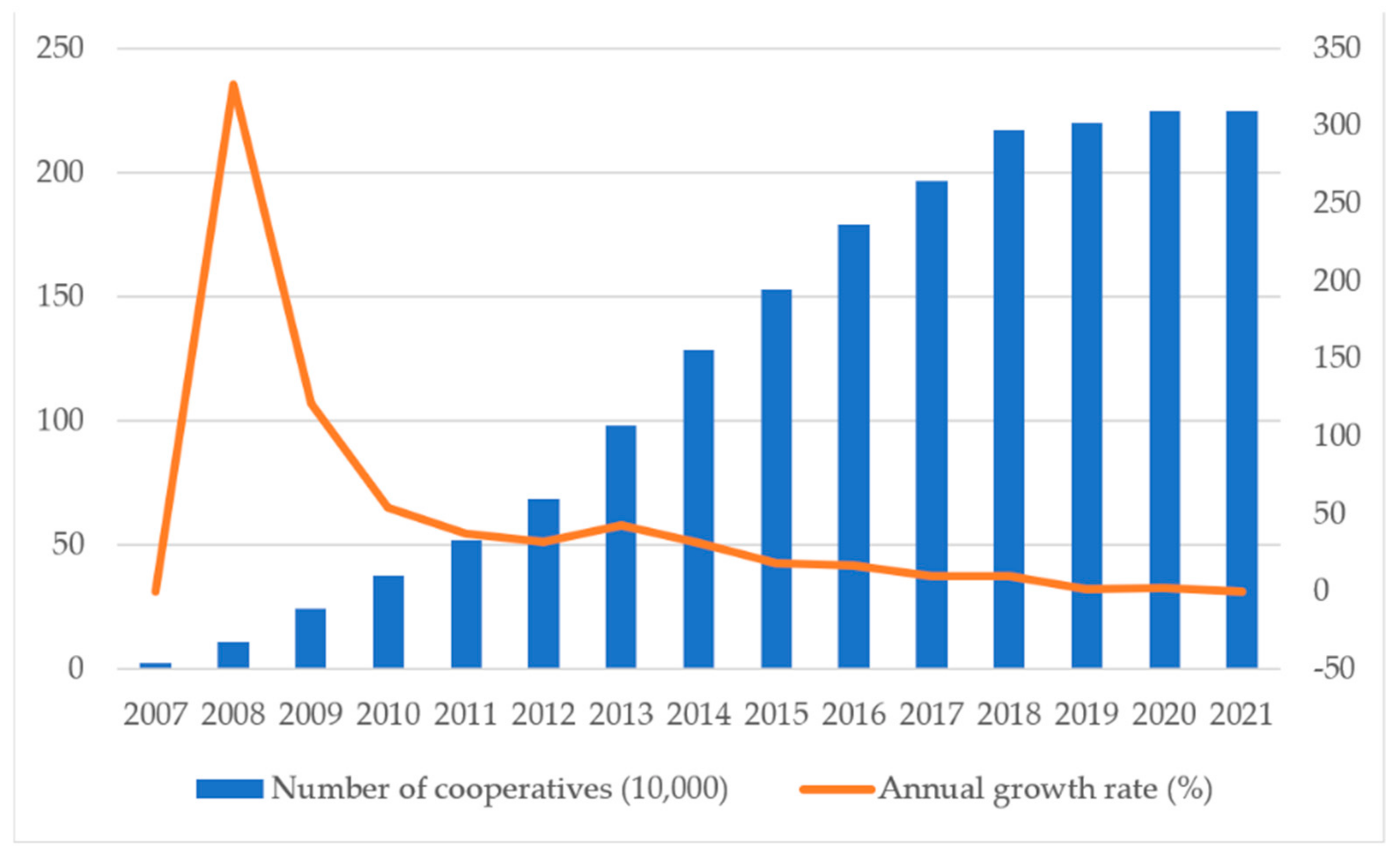

3.1.1. The Number of Cooperatives Has a Declining Trend

3.1.2. Continued Decrease in Average Number of Cooperative Members

3.1.3. Growth Rate and Increase in Members’ Funds

3.1.4. Industrial Distribution Becomes Stable

3.1.5. Cooperatives Led by Capable People Become the Mainstream

3.1.6. Most Cooperatives Provide Sales Services; However, Their Service Ability Is Not Strong

3.1.7. Standardization Degree of Cooperative Production Is Improving Year by Year; However, the Outlook Is Not Optimistic

3.1.8. Distributable Surplus Profit Is Increasing Year by Year; However, It Is Increasing Slowly

3.1.9. Government Support for Cooperatives Shows a Decrease First and Then Increase Approach

3.2. Development Achievements of Chinese Cooperatives

3.2.1. Integration Has Become a Trend

3.2.2. The Function of Cooperatives in Poverty Reduction Is Further Stressed

3.2.3. Cooperatives Can Keep Building Members’ Capacity

3.2.4. Cooperatives Have an Increasing Sense of Social Responsibility

3.2.5. More Alliances between Cooperatives Are Being Established

4. Practices and Effects of Cooperative Quality Improvement Pilot Programs

4.1. Fostering Individual Cooperatives, Diversifying Forms of Investment, and Expanding Business Scope

4.2. Strong Unions Can Further Enhance the Level of Cooperation and Accelerate Integration

4.3. Expanding the Leading Industries and Cultivating New Competitive Advantages with the Focus of Brand Shaping

4.4. Benefit Coupling Mechanism Innovation and New Power for Poverty Alleviation Based on the Principle of Boosting Increased Income

5. Conclusions and Countermeasures of Cooperatives

5.1. Research Conclusions

5.2. Countermeasures and Suggestions

5.2.1. Improving Cooperative Quality

5.2.2. Cultivating Cooperatives’ Inner Force for Development

5.2.3. Improving Market Competitiveness

5.2.4. Enhancing System Construction

5.2.5. Strengthening the Guarantee of Key Elements

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bijman, J.; Hendrikse, G.; Van Oijen, A.J. Accommodating two worlds in one organisation: Changing board models in agricultural cooperatives. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2013, 34, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Heerink, N.; Kruseman, G.; Qu, F. Do fragmented landholdings have higher production costs? Evidence from rice farmers in Northeastern Jiangxi province, PR China. Chin. Econ. Rev. 2008, 19, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wu, B.; Xu, X.; Liang, Q. Situation features and governance structure of farmer cooperatives in China: Does initial situation matter? Soc. Sci. J. 2016, 53, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letter on Reply to Proposal No. 5041 (No. 473 of Agriculture and Water Conservancy) of the Fourth Session of the 13th National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/govpublic/zcggs/202110/t20211009_6378982.htm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Wei, G.; Li, J. Crossroads from incremental to quality improvement: How to standardize and guide the development of cooperatives. China Farm. Coop. 2020, 6, 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- 2021 Sustainable Development Forum to be Held in Beijing. Available online: https://www.drc.gov.cn/DocView.aspx?chnid=382&leafid=1346&docid=2904061 (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- China’s Contribution to Global Sustainable Development. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-10/25/content_5444634.htm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Saleh, A. A Study of the Socioeconomic Determinants of the Performance of the New Lands Cooperatives. Top. Middle East. North Afr. Econ. 2012, 14, 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Qi, G.; Zhang, Y.; Vernooy, R. Farmer cooperatives in China: Diverse pathways to sustainable rural development. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2014, 12, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Nilsson, J. Social Capital and Financial Capital in Chinese Cooperatives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, H. The Ownership of Enterprise; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Enterprise and Industry: Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Available online: http://ec.europa.edu/enterprise/policies/sme/promotingenterpreneurship/socil-economy/co-operatives/index_en.htm (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Xu, Y.; Liang, Q.; Huang, Z. Benefits and pitfalls of social capital for farmer cooperatives: Evidence from China. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 1137–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Hendrikse, G.; Huang, Z.; Xu, X. Governance Structure of Chinese Farmer Cooperatives: Evidence from Zhejiang Province. Agribusiness 2015, 31, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Wei, G. Origin and Evolution of World Agricultural Cooperatives. China Coop. Econ. Rev. 2021, 1, 3–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Adewumi, M.O.; Adebayo, F.J. Profitability and technical efficiency of sweet potato production in Nigeria. J. Rural Dev. 2008, 31, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, C.T.; Francesconi, C.N.; Cetnet, K. Impact of agricultural cooperatives on smallholders’ technical efficiency: Evidence from Ethiopia. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2014, 85, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Abdulai, A. Does cooperative membership improve household welfare? Evidence from apple farmers in China. Food Policy 2016, 58, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.; Qaim, M. Linking Smallholders to Markets: Determinants and Impacts of Farmer Collective Action in Kenya. World Dev. 2012, 40, 1255–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cechin, A.; Bijman, J.; Pascucci, S.; Zylbersztajn, D.; Omta, O. Drivers of pro-active member participation in agricultural cooperatives: Evidence from Brazil. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2013, 84, 443–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Matas, G.; Hernandez-Espallardo, M.; Arcas-Lario, N. Transaction costs in agricultural marketing cooperatives: Effects on market performance. Outlook Agric. 2013, 42, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getnet, K.; Anullo, T. Agricultural cooperatives and rural livelihoods: Evidence from Ethiopia. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2012, 83, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelson, H.; Reardon, T.; Perez, F. Small Farmers and Big Retail: Trade-offs of Supplying Supermarkets in Nicaragua. World Dev. 2012, 40, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, J.; Bao, Z.; Su, Q. Distributional effects of agricultural cooperatives in China: Exclusion of smallholders and potential gains on participation. Food Policy 2012, 37, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Hendrikse, G. Core and common members in the genesis of farmer cooperatives in China. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2013, 34, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Donaldson, J.A. Farmers’ Cooperatives in China: A Typology of Fraud and Failure. China J. 2017, 78, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Andreas, J.; Li, Y. Grapes of Wrath: Twisting Arms to Get Villagers to Cooperate with Agribusiness in China. China J. 2017, 77, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Wei, G. Organizational Reconstruction: Action Guarantee of Rural Revitalization. J. South China Normal Univ. 2021, 05, 108–122. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China issued the “No. 1 Document” of the Central Committee in 2007 (Full Text). Available online: http://www.ce.cn/xwzx/gnsz/szyw/200706/27/t20070627_11973029_1.shtml (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- No. 1 Document of the Central Committee in 2010 (Full Text). Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/xw/zwdt/201002/t20100201_1425496.htm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Document No. 1 of the Central Committee in 2012: The State Council, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China Issued “Several Opinions on Accelerating Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation and Continuously Enhancing the Supply Guarantee Ability of Agricultural Products”. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/nyfzhjsn/zyhwj/201208/t20120830_2901691.htm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Report on the Reform of Rural Collective Property Rights System in the State Council—April 26, 2020 at the 17th Meeting of the 13th the NPC Standing Committee. Available online: http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/c30834/202005/434c7d313d4a47a1b3e9edfbacc8dc45.shtml (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Some Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Accelerating the Development of Modern Agriculture and Further Enhancing the Vitality of Rural Development (Full Text). Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/yhwj2013/zywj/201302/t20130201_3213480.htm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China Issued “Several Opinions on Comprehensively Deepening Rural Reform and Accelerating Agricultural Modernization”. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/gk/zcfg/qnhnzc/201401/t20140121_3743917.htm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Several Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Implementing the New Concept of Development, Accelerating Agricultural Modernization and Realizing the Goal of Overall Well-off Society (Full Text). Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/2016zyyhwj/2016zyyhwj/201601/t20160129_5002063.htm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Several Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Deepening the Structural Reform of Agricultural Supply Side and Accelerating the Cultivation of New Kinetic Energy of Agricultural and Rural Development. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/yhwj2017/zywj/201702/t20170206_5468567.htm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Notice on Printing and Distributing the Special Clean-up Work Plan for “Empty Shell Society” of Farmers’ Professional Cooperatives. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/nybgb/2019/0201903/201905/t20190525_6315400.htm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Several Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Adhering to the Priority Development of Agriculture and Rural Areas and Doing a Good Job in “Agriculture, Countryside and Farmers”. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/jj2019zyyhwj/2019zyyhwj/201902/t20190220_6172154.htm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Comprehensively Promoting Rural Revitalization and Accelerating Agricultural and Rural Modernization. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/jj2021zyyhwj/2021nzyyhwj/202102/t20210221_6361867.htm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Twenty-One of the Five-Year Series Propaganda of Agricultural Modernization: Farmers’ Cooperatives to Achieve Standardized Promotion. Available online: http://www.jhs.moa.gov.cn/ghgl/202106/t20210617_6369793.htm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.W. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. The impact of social structure on economic outcomes. J. Econ. Perspect. 2005, 19, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulos, C.; Valentinov, V. Cooperative Longevity: Why Are So Many Cooperatives So Successful? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Ronco, A.; Guzman-Asuncion, S. Determinants of financing decisions and management implications: Evidence from Spanish agricultural cooperatives. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Victoria, M.; Sanchez-Val, M.M.; Arcas-Lario, N. Spatial determinants of productivity growth on agri-food Spanish firms: A comparison between cooperatives and investor-owned firms. Agric. Econ. 2018, 49, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Fu, Y.; Liang, Q.; Song, Y.; Xu, X. The efficiency of agricultural marketing cooperatives in China’s Zhejiang province. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2013, 34, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.; Svendsen, G.L.H.; Svendsen, G.T. Are Large and Complex Agricultural Cooperatives Losing Their Social Capital? Agribusiness 2012, 28, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efendiev, A.; Sorokin, P. Rural social organization and farmer cooperatives development in Russia and other emerging economies: Comparative analysis. Dev. Ctry. Stud. 2013, 3, 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G.; Ma, X. Promote the high-quality development of standardized cooperatives. China Coop. Econ. Rev. 2021, 1, 85–91. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Law of People’s Republic of China (PRC) on Farmers’ Professional Cooperatives. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-12/28/content_5251064.htm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Yang, D.; Liu, Z. Does farmer economic organization and agricultural specialization improve rural income? Evidence from China. Econ. Model. 2012, 29, 990–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirezieva, K.; Bijman, J.; Jacxsens, L.; Luning, P.A. The role of cooperatives in food safety management of fresh produce chains: Case studies in four strawberry cooperatives. Food Control 2016, 62, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Bijman, J.; Gardebroek, C.; Heerink, N.; Heijman, W.; Huo, X. Cooperative membership and farmers’ choice of marketing channels—Evidence from apple farmers in Shaanxi and Shandong Provinces, China. Food Policy 2018, 74, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, A.; Gutierrez, I.; Sibelet, N.; Faure, G. Small farmer cooperatives and voluntary coffee certifications: Rewarding progressive farmers of engendering widespread change in Costa Rica? Food Policy 2017, 69, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Saroj, S.; Joshi, P.; Takeshima, H. Does cooperative membership improve household welfare? Evidence from a panel data analysis of smallholder dairy farmers in Bihar, India. Food Policy 2018, 75, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Hendrikse, G. Pooling and the yardstick effect of cooperatives. Agric. Syst. 2016, 143, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, K.; Liang, Q. Food safety controls in different governance structures in China’s vegetable and fruit industry. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14, 2189–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, Q.E. The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. J. Econ. Lit. 2000, 38, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Lu, H.; Deng, W. Between social capital and formal governance in farmer cooperatives: Evidence from China. Outlook Agric. 2018, 47, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, I.; Hviid, M.; Sharp, P. Law and Peace: Contracts and the Success of the Danish Dairy Cooperatives. J. Econ. Hist. 2012, 72, 197–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.A. Going back to go forwards? From multi-stakeholder cooperatives to Open Cooperatives in food and farming. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 53, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonte, M.; Cucco, I. Cooperatives and alternative food networks in Italy. The long road towards a social economy in agriculture. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 53, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grashuis, J.; Magnier, A. Product differentiation by marketing and processing cooperatives: A choice experiment with cheese and cereal products. Agribusiness 2018, 34, 813–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagwiza, C.; Muradian, R.; Ruben, R. Cooperative membership and dairy performance among smallholders in Ethiopia. Food Policy 2016, 59, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wei, G. Leading the rural industrial integration and development with innovative ideas. China Econ. Trade Guide 2021, 3, 101–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mojo, D.; Fischer, C.; Degefa, T. The determinants and economic impacts of membership in coffee farmer cooperatives: Recent evidence from rural Ethiopia. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 50, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoken, H.; Su, Q. Measuring the effect of agricultural cooperatives on household income: Case study of a rice-producing cooperative in China. Agribusiness 2018, 34, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2022 Analysis Report on the Development of New Agricultural Business Subjects in China (II)—Based on the Survey of Farmers’ Cooperatives in China. Available online: http://www.farmer.com.cn/2022/12/27/99904362.html (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Reply of the General Office of the Ministry of Agriculture on the Pilot Implementation Plan of Promoting the Quality Improvement of National Farmers’ Professional Cooperatives in the Whole County. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/govpublic/NCJJTZ/201902/t20190212_6171244.htm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Benos, T.; Kalogeras, N.; Verhees, F.; Sergaki, P.; Pennings, J. Cooperatives’ Organizational Restructuring, Strategic Attributes, and Performance: The Case of Agribusiness Cooperatives in Greece. Agribusiness 2016, 32, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Chen, Q.; Trienekens, J.; Wang, H. Determinants of cooperative pig farmers’ safe production behaviour in China—Evidences from perspective of cooperatives’ services. J. Integr. Agric. 2018, 17, 2345–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Ma, W.; Su, Y. Effects of member size and selective incentives of agricultural cooperatives on product quality. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 858–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of cooperatives (unit: 10,000) | 24.6 | 37.9 | 52.2 | 68.9 | 153.1 | 179.4 | 196.9 | 217.3 | 220.3 |

| Total number of memberships (unit: 10,000 households) | 391.7 | 715.6 | 1196.4 | 2373.4 | 10,090 | 10,080 | 6894.3 | 7191.9 | 6682.8 |

| Average number of memberships in each cooperative (household) | 15 | 18 | 22 | 34 | 65 | 60 | 38 | 38 | 35 |

| Year | Members’ Funds (Trillion CNY) | Average Funds per Cooperative (CNY 10,000) | Average Funds of Members’ (CNY 10,000) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 0.03 | 113.64 | - |

| 2008 | 0.09 | 81.15 | - |

| 2009 | 0.25 | 101.46 | 6.38 |

| 2010 | 0.45 | 118.70 | 6.29 |

| 2011 | 0.72 | 138.01 | 6.02 |

| 2012 | 1.1 | 159.67 | 4.63 |

| 2013 | 1.89 | 192.39 | - |

| 2014 | 2.73 | 211.82 | - |

| 2015 | 3.23 | 210.96 | 3.20 |

| 2016 | 4.1 | 228.54 | 3.80 |

| Year | Planting | Animal Husbandry | Service Industry | Forestry | Fishing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume | % | Volume | % | Volume | % | Volume | % | Volume | % | |

| 2011 | 24.6 | 48.3 | 14.4 | 28.2 | 4.6 | 9.0 | 2.6 | 5.1 | 2.0 | 3.9 |

| 2012 | 30.6 | 48.2 | 17.7 | 27.9 | 5.8 | 9.1 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 2.5 | 3.9 |

| 2013 | 44.8 | 50.6 | 22.7 | 25.7 | 7.7 | 8.7 | 5.1 | 5.8 | 3.3 | 3.7 |

| 2014 | 60.0 | 50.6 | 28.5 | 25 | 9.3 | 8.2 | 6.6 | 5.8 | 4.0 | 3.5 |

| 2015 | 71.0 | 53.2 | 32.4 | 24.3 | 10.9 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 5.9 | 4.5 | 3.4 |

| 2016 | 84.3 | 54.0 | 37.1 | 23.7 | 12.3 | 7.9 | 9.2 | 5.9 | 5.1 | 3.3 |

| 2017 | 95.4 | 54.4 | 40.4 | 23.1 | 13.9 | 7.9 | 10.4 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 3.0 |

| 2018 | 103.6 | 54.7 | 42.8 | 22.6 | 14.7 | 7.7 | 11.3 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 3.2 |

| 2019 | 105.6 | 54.6 | 40.9 | 21.1 | 15.4 | 8.0 | 11.7 | 6.0 | 5.9 | 3.0 |

| Year | Leader Types | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capable People | Village Cadres | Enterprises | Technical Promotion Organizations | Others | ||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2011 | 45.8 | 89.9 | 9.2 | 20.1 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 1 | 2 | 2.6 | 5.2 |

| 2012 | 57.2 | 90.3 | 10.8 | 18.9 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 4.9 |

| 2013 | 80.2 | 90.7 | 13.6 | 16.9 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 4.3 | 4.8 |

| 2014 | 103.5 | 91 | 15.6 | 15.1 | 3 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 5.4 | 4.8 |

| 2015 | 121.6 | 91 | 17.3 | 12.9 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 6.5 | 4.9 |

| 2016 | 142.4 | 91.2 | 19.1 | 13.4 | 3.8 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 7.5 | 4.8 |

| 2017 | 160 | 91.2 | 21.2 | 12 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 1.5 | 8.6 | 5 |

| 2018 | 172.6 | 91.2 | 23 | 12.1 | 4.4 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 9.4 | 4.9 |

| 2019 | 164.4 | 85.0 | 23 | 11.9 | 4.1 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 9.4 | 4.9 |

| Year | Production, Processing, and Sales | Production | Purchasing | Storage | Transportation and Sales | Processing | Others | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2011 | 26.6 | 52.3 | 13.7 | 26.9 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 3.3 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 5.5 | 10.9 |

| 2012 | 33.1 | 52.2 | 16.9 | 22.7 | 2.5 | 3.9 | 5.7 | 0.9 | 2 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 6.9 | 10.9 |

| 2013 | 46.3 | 52.4 | 24.6 | 27.8 | 3.5 | 4 | 7.1 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 8.7 | 9.9 |

| 2014 | 60.6 | 53.3 | 31.8 | 28 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 1 | 0.9 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2 | 10.7 | 9.4 |

| 2015 | 70.7 | 52.9 | 38.1 | 28.5 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2 | 13.1 | 9.8 |

| 2016 | 83 | 53.1 | 44.8 | 28.7 | 6.1 | 3.4 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 2 | 17 | 9.5 |

| 2017 | 93.1 | 53.1 | 50.9 | 29 | 5.8 | 3.3 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 2 | 16.7 | 9.5 |

| 2018 | 101.1 | 53.4 | 54.6 | 28.8 | 6 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 3.9 | 2 | 3.8 | 2 | 18.3 | 9.7 |

| 2019 | 104.2 | 53.9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8.4 | 4.3 | 6 | 3.1 | - | - |

| Year | Cooperatives with Registered Trademarks | Cooperatives with Product Quality Certifications | Model Cooperatives | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2011 | 4 | 7.8 | 2.1 | 4 | 6.5 | 12.5 |

| 2012 | 4.7 | 6.8 | 2.8 | 4.1 | 7 | 10.2 |

| 2013 | 6 | 6.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 9.1 | 9.3 |

| 2014 | 7 | 5.4 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 10.7 | 8.3 |

| 2015 | 7.5 | 4.9 | 4 | 2.6 | 12.7 | 8.3 |

| 2016 | 8.1 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 14 | 7.8 |

| 2017 | 8.5 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 2.7 | 14.9 | 8.5 |

| 2018 | 8.7 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 2.4 | 16 | 8.5 |

| 2019 | 10.6 | 5.5 | 5 | 2.6 | 15.7 | 8.1 |

| Year | Cooperative’s Distributable Surplus Profit (CNY 100 Million) | Average Distributable Surplus Profit per Cooperative (CNY 10,000) | Distributable Surplus Profit per Member (CNY) | Farmer Cooperatives That Distribute Profit Based on Transaction Volume (10,000 Cooperatives) | Farmer Cooperatives That Distribute More than 60% of Profit to Farmers (10,000 Cooperatives) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 419.6 | 9.7 | 1426 | 11.5 | 8.3 |

| 2012 | 575.3 | 9.1 | 1300 | 14.9 | 10.8 |

| 2013 | 767.4 | 8.7 | 1611 | 21.1 | 16 |

| 2014 | 907 | 8 | 1600 | 26.7 | 20.6 |

| 2015 | 945.1 | 7.1 | 1689 | 29.4 | 22.7 |

| 2016 | 999.5 | 6.4 | 1559 | 33.7 | 25.9 |

| 2017 | 1116.9 | 6.4 | 1644 | 36.8 | 27.7 |

| 2018 | 1008.7 | 5.3 | 1403 | 38 | 29.4 |

| 2019 | 1123.4 | 5.8 | 1681 | 36.9 | 28.4 |

| Indicator | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cooperatives receiving government financial assistance (10,000 units) | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 3.8 |

| Total special financial assistance from all levels of government (CNY 100 million) | 55 | 54.7 | 46 | 48.3 | 65.1 | 68.1 | 68.2 |

| Average amount of financial assistance received per cooperative (CNY 10,000) | 16 | 15.5 | 13.9 | 14.7 | 18.2 | 18.1 | 17.9 |

| Yearly loan balance (CNY 100 million) | 56.3 | 106 | 113 | - | 90.6 | 79.3 | 84.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, X.; Wei, G.; Kong, X. The Future of Agriculture: Obstacles and Improvement Measures for Chinese Cooperatives to Achieve Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15020974

Qu Y, Zhang J, Wang Z, Ma X, Wei G, Kong X. The Future of Agriculture: Obstacles and Improvement Measures for Chinese Cooperatives to Achieve Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):974. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15020974

Chicago/Turabian StyleQu, Yi, Jing Zhang, Zhenning Wang, Xinning Ma, Guangcheng Wei, and Xiangzhi Kong. 2023. "The Future of Agriculture: Obstacles and Improvement Measures for Chinese Cooperatives to Achieve Sustainable Development" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15020974

APA StyleQu, Y., Zhang, J., Wang, Z., Ma, X., Wei, G., & Kong, X. (2023). The Future of Agriculture: Obstacles and Improvement Measures for Chinese Cooperatives to Achieve Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 15(2), 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15020974