Green FinTech Innovation as a Future Research Direction: A Bibliometric Analysis on Green Finance and FinTech

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Findings and Discussion

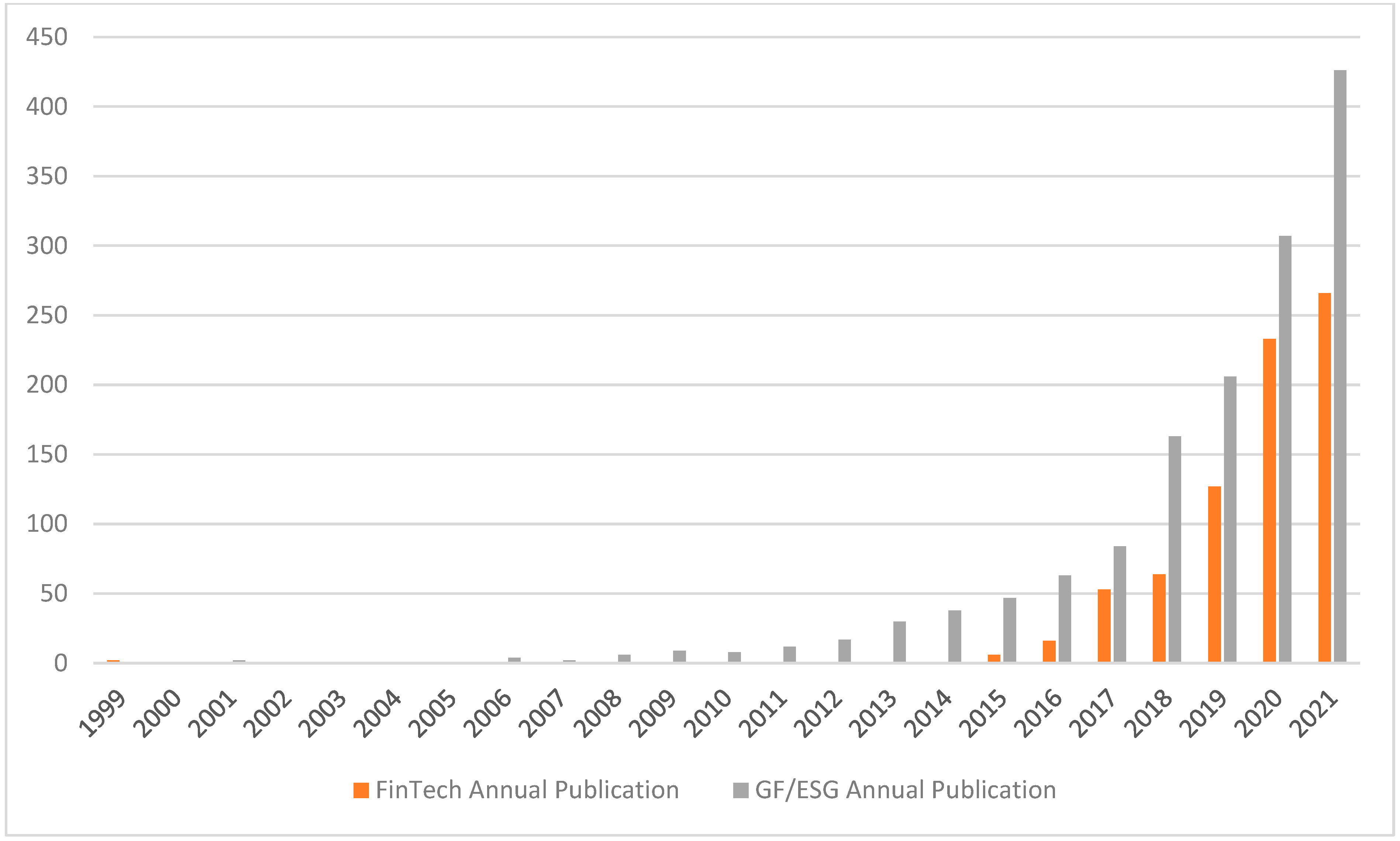

3.1. Total Publications

3.2. Keywords Analysis

3.3. Co-Word Analysis

3.4. Network Analysis of GF/ESG and FinTech

3.4.1. Application Aspect of FinTech

3.4.2. Regulatory Aspect of FinTech

3.5. Country of Origin

3.6. Most Cited Papers

| No. | Author(s)/Year | Journal | Title | Local Citations | Global Citations | LC/GC Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fatemi et al. (2018) [31] | Global Finance Journal | ESG performance and firm value: The moderating role of disclosure | 72 | 199 | 36.18 |

| 2 | Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim (2018) [32] | Financial Analysts Journal | Why and How Investors Use ESG Information: Evidence from a Global Survey | 66 | 171 | 38.6 |

| 3 | Nofsinger and Varma (2014) [33] | Journal of Banking and Finance | Socially responsible funds and market crises | 59 | 189 | 31.22 |

| 4 | Broadstock et al. (2021) [34] | Finance Research Letters | The role of ESG performance during times of financial crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China | 56 | 148 | 37.84 |

| 5 | Galbreath (2013) [35] | Journal of Business Ethics | ESG in Focus: The Australian Evidence | 55 | 110 | 50 |

| 6 | Van Duuren et al. (2016) [47] | Journal of Business Ethics | ESG Integration and the Investment Management Process: Fundamental Investing Reinvented | 53 | 130 | 40.77 |

| 7 | Nollet et al. (2016) [48] | Economic Modelling | Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A non-linear and disaggregated approach | 52 | 193 | 26.94 |

| 8 | Velte (2017) [36] | Journal of Global Responsibility | Does ESG performance have an impact on financial performance? Evidence from Germany | 48 | 115 | 41.74 |

| 9 | Aouadi and Marsat (2018) [37] | Journal of Business Ethics | Do ESG Controversies Matter for Firm Value? Evidence from International Data | 45 | 132 | 34.09 |

| 10 | Duque-Grisales and Aguilera-Caracuel (2021) [49] | Journal of Business Ethics | Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Scores and Financial Performance of Multilatinas: Moderating Effects of Geographic International Diversification and Financial Slack | 42 | 120 | 35 |

| 11 | Xie et al. (2019) [38] | Business Strategy and the Environment | Do environmental, social, and governance activities improve corporate financial performance? | 37 | 158 | 23.42 |

| 12 | Krueger et al. (2020) [50] | The Review of Financial Studies | The Importance of Climate Risks for Institutional Investors | 37 | 176 | 21.02 |

| 13 | Baldini et al. (2018) [51] | Journal of Business Ethics | Role of Country- and Firm-Level Determinants in Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure | 36 | 115 | 31.3 |

| 14 | Pedersen et al. (2021) [39] | Journal of Financial Economics | Responsible investing: The ESG-efficient frontier | 36 | 90 | 40 |

| 15 | Taghizadeh-Hesary and Yoshino (2019) [52] | Finance Research Letters | The way to induce private participation in green finance and investment | 33 | 207 | 15.94 |

| 16 | Ng and Rezaee (2015) [53] | Journal of Corporate Finance | Business sustainability performance and cost of equity capital | 29 | 136 | 21.32 |

| 17 | Mervelskemper and Streit (2017) [54] | Business Strategy and the Environment | Enhancing Market Valuation of ESG Performance: Is Integrated Reporting Keeping its Promise? | 29 | 104 | 27.88 |

| 18 | Stellner et al. (2015) [55] | Journal of Banking and Finance | Corporate social responsibility and Eurozone corporate bonds: The moderating role of country sustainability | 28 | 104 | 26.92 |

| 19 | Semenova and Hassel (2015) [56] | Journal of Business Ethics | On the Validity of Environmental Performance Metrics | 28 | 93 | 30.11 |

| 20 | Tang and Zhang (2020) [5] | Journal of Corporate Finance | Do shareholders benefit from green bonds | 28 | 152 | 18.42 |

| No. | Author(s)/Year | Journal | Title | Local Citations | Global Citations | LC/GC Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Buchak et al. (2018) [40] | Journal of Financial Economics | Fintech, regulatory arbitrage, and the rise of shadow banks | 74 | 214 | 34.58 |

| 2 | Thakor (2020) [41] | Journal of Financial Intermediation | Fintech and banking: What do we know? | 51 | 121 | 42.15 |

| 3 | Fuster et al. (2019) [42] | The Review of Financial Studies | The Role of Technology in Mortgage Lending | 48 | 112 | 42.86 |

| 4 | Tang (2019) [43] | The Review of Financial Studies | Peer-to-Peer Lenders Versus Banks: Substitutes or Complements? | 45 | 110 | 40.91 |

| 5 | Chen et al. (2019) [44] | The Review of Financial Studies | How Valuable Is FinTech Innovation? | 35 | 110 | 31.82 |

| 6 | Jagtiani and Lemieux (2018) [57] | Journal of Economics and Business | Do fintech lenders penetrate areas that are underserved by traditional banks? | 33 | 78 | 42.31 |

| 7 | Anagnostopoulos (2018) [58] | Journal of Economics and Business | Fintech and regtech: Impact on regulators and banks | 29 | 93 | 31.18 |

| 8 | Ozili (2018) [59] | Borsa Istanbul Review | Impact of digital finance on financial inclusion and stability | 24 | 208 | 11.54 |

| 9 | Foley et al. (2019) [60] | Review of Financial Studies | Sex, Drugs, and Bitcoin: How Much Illegal Activity Is Financed through Cryptocurrencies? | 20 | 203 | 9.85 |

| 10 | Drasch et al. (2018) [61] | Journal of Economics and Business | Integrating the ‘Troublemakers’: A taxonomy for cooperation between banks and fintechs | 18 | 46 | 39.13 |

| 11 | Adhami et al. (2018) [62] | Journal of Economics and Business | Why do businesses go crypto? An empirical analysis of initial coin offerings | 17 | 166 | 10.24 |

| 12 | Jagtiani and Lemieux (2019) [45] | Financial Management | The roles of alternative data and machine learning in fintech lending: Evidence from the LendingClub consumer platform | 16 | 45 | 35.56 |

| 13 | Cong and He (2019) [63] | The Review of Financial Studies | Blockchain Disruption and Smart Contracts | 14 | 224 | 6.25 |

| 14 | Gimpel et al. (2018) [64] | Electronic Markets | Understanding FinTech start-ups—a taxonomy of consumer-oriented service offerings | 13 | 67 | 19.4 |

| 15 | Chiu and Koeppl (2019) [46] | The Review of Financial Studies | Blockchain-Based Settlement for Asset Trading | 13 | 61 | 21.31 |

| 16 | Zhu (2019) [65] | The Review of Financial Studies | Big Data as a Governance Mechanism | 12 | 38 | 31.58 |

| 17 | Begenau et al. (2018) [66] | Journal of Monetary Economics | Big data in finance and the growth of large firms | 11 | 40 | 27.5 |

| 18 | Zalan and Toufaily (2017) [67] | Contemporary Economics | The Promise of Fintech in Emerging Markets: Not as Disruptive | 10 | 31 | 32.26 |

| 19 | Ashta and Biot-Paquerot (2018) [68] | Strategic Change | FinTech evolution: Strategic value management issues in a fast changing industry | 10 | 32 | 31.25 |

| 20 | Stulz (2019) [69] | Journal of Applied Corporate Finance | FinTech, BigTech, and the Future of Banks | 10 | 27 | 37.04 |

3.7. Co-Citation Analysis

3.8. Sources of GF/ESG and FinTech Literature

3.9. Attention on Green FinTech

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- YPCCC. Available online: https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/global-warmings-six-americas-september-2021/ (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Durrani, A.; Rosmin, M.; Volz, U. The role of central banks in scaling up sustainable finance—What do monetary authorities in the Asia-Pacific region think? J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2020, 10, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NGFS. Available online: https://www.ngfs.net/en/about-us/membership (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- SBFN. Available online: https://www.sbfnetwork.org/ (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Tang, D.Y.; Zhang, Y. Do shareholders benefit from green bonds? J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 61, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate green bonds. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malais, A.; Nykvist, B. Understanding the role of green bonds in advancing sustainability. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelet, M.J.; Becchetti, L.; Manfredonia, S. The green bonds premium puzzle: The role of issuer characteristics and third-party verification. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, O. How to trust green bonds: Blockchain, climate, and the institutional bond markets. In Transforming Climate Finance and Green Investment with Blockchains; Marke, A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- Dorfleitner, G.; Braun, D. Fintech, digitalization and blockchain: Possible applications for green finance. In The Rise of Green Finance in Europe; Migliorelli, M., Dessertine, P., Eds.; Palgrave Studies in Impact Finance; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 207–237. [Google Scholar]

- Malamas, V.; Dasaklis, T.; Arakelian, V.; Chondrokoukis, G. A Block-Chain Framework for Increased Trust in Green Bonds Issuance. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3693638 (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Ruan, J.H.; Wang, Y.X.; Chan, F.T.S.; Hu, X.P.; Zhao, M.J.; Zhu, F.W.; Shi, B.F.; Shi, Y.; Lin, F. A life-cycle framework of green IoT-based agriculture and its finance, operation, and management issues. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2019, 57, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.K.; Kumar, N.; Park, J.H. Blockchain technology toward green IoT: Opportunities and challenges. IEEE Netw. 2020, 34, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrah, C.; Darko, A.; Chan, A.P.C. A bibliometric-qualitative literature review of green finance gap and future research directions. Clim. Dev. 2023, 15, 432–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Su, X.; Yao, S. Nexus between green finance, fintech, and high-quality economic development: Empirical evidence from China. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhwaldi, A.F.; Alharasis, E.E.; Shehadeh, M.; Abu-AlSondos, I.A.; Oudat, M.S.; Bani Atta, A.A. Towards an Understanding of FinTech Users’ Adoption: Intention and e-Loyalty Post-COVID-19 from a Developing Country Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchiri, M.K.; Erdei-Gally, S.; Fekete-Farkas, M.; Lakner, Z. Bibliometric analysis of green finance and climate change in post-Paris agreement era. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A.; Shaukat, K.; Iqbal Khan, K.; Hameed, I.A.; Alam, T.M.; Luo, S. Trends and directions of financial technology (Fintech) in society and environment: A bibliometric study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H. Visualising science through citation mapping. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1999, 50, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I.; Cater, T. Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyons, E.C.; Moed, H.F.; Luwel, M. Combining mapping and citation analysis for evaluative bibliometric purposes: A bibliometric study. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1999, 50, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Raan, A.F. For your citations only? Hot topics in bibliometric analysis. Measurement 2005, 3, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.J.; Lopez-Herrera, A.G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. Science mapping software tools: Review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 1382–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltrinieri, A.; Hassan, M.I.; Bahoo, S.; Khan, A. A bibliometric review of sukuk literature. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 86, 897–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckute, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Managi, S. A bibliometric analysis on green finance: Current status, development, and future directions. Financ. Res. Lett. 2019, 29, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Hassan, M.K.; Paltrinieri, A.; Dreassi, A.; Bahoo, S. A bibliometric review of takaful literature. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2020, 69, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Yan, E.; Frazho, A.; Caverlee, J. PageRank for ranking authors in co-citation networks. J. Am Soc. Inf. Sci. 2009, 60, 2229–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, A.; Glaum, M.; Kaiser, S. ESG performance and firm value: The moderating role of disclosure. Glob. Financ. J. 2018, 38, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel-Zadeh, A.; Serafeim, G. Why and how investors use ESG information: Evidence from a global survey. Financ. Anal. J. 2018, 74, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofsinger, J.; Varma, A. Socially responsible funds and market crises. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 48, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, D.C.; Chan, K.; Cheng, L.T.; Wang, X. The role of ESG performance during times of financial crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 38, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. ESG in focus: The Australian evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. Does ESG performance have an impact on financial performance? Evidence from Germany. J. Glob. Responsib. 2017, 8, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouadi, A.; Marsat, S. Do ESG controversies matter for firm value? Evidence from international date. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Nozawa, W.; Yagi, M.; Fujii, H.; Managi, S. Do environmental, social, and governance activities improve corporate financial performance? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, L.H.; Fitzgibbons, S.; Pomorski, L. Responsible investing: The EST-efficient frontier. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 572–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchak, G.; Matvos, G.; Piskorski, T.; Seru, A. Fintech, regulatory arbitrage, and the rise of shadow banks. J. Financ. Econ. 2018, 130, 453–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakor, A.V. Fintech and banking: What do we know? J. Financ. Intermediat. 2020, 41, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, A.; Plosser, M.; Schnabi, P.; Vickery, J. The role of technology in mortgage lending. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 1854–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H. Peer-to-peer lenders versus banks: Substitutes or complements? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 1900–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.A.; Wu, Q.; Yang, B. How valuable is FinTech innovation? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 2062–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtiani, J.; Lemieux, C. The roles of alternative data and machine learning in fintech lending: Evidence from the LendingClub consumer platform. Financ. Manag. 2019, 48, 1009–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J.; Koeppl, T.V. Blockchain-based settlement for asset trading. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 1716–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duuren, E.; Plantinga, A.; Scholtens, B. ESG integration and the investment management process: Fundamental investing reinvented. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nollet, J.; Filis, G.; Mitrokostas, E. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A non-linear and disaggregated approach. Econ. Model. 2016, 52, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Grisales, E.; Auilera-Caracuel, J. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores and financial performance of multilatinas: Moderating effects of geographic international diversification and financial slack. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 168, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, P.; Sautner, Z.; Starks, L.T. The importance of climate risks for institutional investors. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020, 33, 1067–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, M.; Maso, L.D.; Liberatore, G.; Mazzi, F.; Terzani, S. Role of country-and firm-level determinants in environmental, social, and governance disclosure. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Yoshino, N. The way to induce private participation in green finance and investment. Financ. Res. Lett. 2019, 31, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.C.; Rezaee, Z. Business sustainability performance and cost of equity capital. J. Corp. Financ. 2015, 34, 128–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mervelskemper, L.; Streit, D. Enhancing market valuation of ESG performance: Is integrated reporting keeping its promise? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellner, C.; Klein, C.; Zwergel, B. Corporate social responsibility and Eurozone corporate bonds: The moderating role of country sustainability. J. Bank. Financ. 2015, 59, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, N.; Hassel, L.G. On the validity of environmental performance metrics. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtiani, J.; Lemieux, C. Do fintech lenders penetrate areas that are underserved by traditional banks? J. Econ. Bus. 2018, 100, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, I. Fintech and regtech: Impact on regulators and banks. J. Econ. Bus. 2018, 100, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. Impact of digital finance on financial inclusion and stability. Borsa Istab. Rev. 2018, 18, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, S.; Karlsen, J.R.; Putnins, T.J. Sex, drugs, and bitcoin: How much illegal activity is financed through cryptocurrencies? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 1798–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drasch, B.J.; Schweizer, A.; Urbach, N. Integrating the ‘Troublemakers’: A taxonomy for cooperation between banks and fintechs. J. Econ. Bus. 2018, 100, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhami, S.; Giudici, G.; Martinazzi, S. Why do businesses go crypto? An empirical analysis of initial coin offerings. J. Econ. Bus. 2018, 100, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.W.; He, Z. Blockchain disruption and smart contracts. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 1754–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimpel, H.; Rau, D.; Roglinger, M. Understanding FinTech start-ups—A taxonomy of consumer-oriented service offerings. Electron. Mark. 2018, 28, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C. Big data as a governance mechanism. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 2021–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begenau, J.; Farboodi, M.; Veldkamp, L. Big data in finance and the growth of large firms. J. Monet. Econ. 2018, 97, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalan, T.; Toufaily, E. The promise of fintech in emerging markets: Not as disruptive. Contemp. Econ. 2017, 11, 415–431. [Google Scholar]

- Ashta, A.; Biot-Paquerot, G. FinTech evolution: Strategic value management issues in a fast changing industry. Strateg. Chang. 2018, 27, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulz, R.M. Fintech, bigtech, and the future of banks. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2019, 31, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorland, B. Facet analysis: The logical approach to knowledge organization. Inf. Process. Manag. 2013, 49, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Liu, W.; Dunford, M. Visualizing the intellectual structure and evolution of innovation systems research: A bibliometric analysis. Scientometrics 2015, 103, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, D.E.; Bernardes, R.C.; Borini, F.M.; Gattaz, C.C. Structure and evolution of innovation research in the last 60 years: Review and future trends in the field of business through the citations and co-citations analysis. Scientometrics 2018, 115, 1329–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D.S.; Li, O.Z.; Tsang, A.; Yang, Y.G. Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure and the Cost of Equity Capital: The Initiation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 59–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D.S.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Tsang, A.; Yang, Y.G. Nonfinancial disclosure and analyst forecast accuracy: International evidence on corporate social responsibility disclosure. Account. Rev. 2012, 87, 723–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Serafeim, G.; Krzus, M.P. Market interest in nonfinancial information. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2011, 23, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. La responsabilidad social de la empresa es incrementar sus beneficios. NY Times Mag. 1970, 13, 122–126. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, J.J.; Mahon, J.F. The corporate social performance and corporate financial performance debate: Twenty-five years of incomparable research. Bus. Soc. 1997, 36, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.M.; Palepu, K.G. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 31, 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Keim, G.D. Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: What’s the bottom line? Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. What drives corporate social performance? The role of nation-level institutions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 834–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.; Meckling, W. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs, and Ownership Structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Harjoto, M.A. Corporate governance and firm value: The impact of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Walsh, J.P. Misery loves companies: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Adm. Sci. Q. 2003, 48, 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Correlation or misspecification? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The corporate social performance–financial performance link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Salomon, R.M. Beyond dichotomy: The curvilinear relationship between social responsibility and financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 1101–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.; Koedijk, K.; Otten, R. International evidence on ethical mutual fund performance and investment style. J. Bank. Financ. 2005, 29, 1751–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart, M.M. On persistence in mutual fund performance. J. Financ. 1997, 52, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwall, J.; Guenster, N.; Bauer, R.; Koedijk, K. The eco-efficiency premium puzzle. Financ. Anal. J. 2005, 61, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimson, E.; Karakaş, O.; Li, X. Active ownership. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2015, 28, 3225–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmans, A. Does the stock market fully value intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices. J. Financ. Econ. 2011, 101, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. The cross-section of expected stock returns. J. Financ. 1992, 47, 427–465. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. J. Financ. Econo. 1993, 33, 3–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. A five-factor asset pricing model. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 116, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galema, R.; Plantinga, A.; Scholtens, B. The stocks at stake: Return and risk in socially responsible investment. J. Bank. Financ. 2008, 32, 2646–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinkel, R.; Kraus, A.; Zechner, J. The effect of green investment on corporate behavior. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2001, 36, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Kacperczyk, M. The price of sin: The effects of social norms on markets. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 93, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Corporate sustainability: First evidence on materiality. Account. Rev. 2016, 91, 1697–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renneboog, L.; Ter Horst, J.; Zhang, C. Socially responsible investments: Institutional aspects, performance, and investor behavior. J. Bank. Financ. 2008, 32, 1723–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statman, M.; Glushkov, D. The wages of social responsibility. Financ. Anal. J. 2009, 65, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénabou, R.; Tirole, J. Individual and corporate social responsibility. Economica 2010, 77, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterji, A.K.; Levine, D.I.; Toffel, M.W. How well do social ratings actually measure corporate social responsibility? J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2009, 18, 125–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O.; Kwok, C.C.; Mishra, D.R. Does corporate social responsibility affect the cost of capital? J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 2388–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, A.; Liang, H.; Renneboog, L. Socially responsible firms. J. Financ. Econ. 2016, 122, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C.; Merrill, C.B.; Hansen, J.M. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, A.; Roberts, G.S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on the cost of bank loans. J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 1794–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, P. Corporate goodness and shareholder wealth. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 115, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, K.V.; Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. The impact of corporate social responsibility on firm value: The role of customer awareness. Manag. Sci. 2013, 59, 1045–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfman, M.P.; Fernando, C.S. Environmental risk management and the cost of capital. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 569–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomber, P.; Kauffman, R.J.; Parker, C.; Weber, B.W. On the fintech revolution: Interpreting the forces of innovation, disruption, and transformation in financial services. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2018, 35, 220–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, C.; Hornuf, L. The emergence of the global fintech market: Economic and technological determinants. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 53, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Shin, Y.J. Fintech: Ecosystem, business models, investment decisions, and challenges. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. White Paper. 2008. Available online: http://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Lin, M.; Prabhala, N.R.; Viswanathan, S. Judging borrowers by the company they keep: Friendship networks and information asymmetry in online peer-to-peer lending. Manag. Sci. 2013, 59, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Qian, J.; Yu, M. Analysis of green financial policy utility: A policy incentive financial mechanism based on state space model theory algorithm. J. Sens. 2022, 2022, 5978122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Research on the impact mechanism of green finance on the green innovation performance of China’s manufacturing industry. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2021, 43, 2678–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puschmann, T.; Hoffmann, C.H.; Khmarskyi, V. How green FinTech can alleviate the impact of climate change—The case of Switzerland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macciavello, E.; Siri, M. Sustainable finance and fintech: Can technology contribute to achieving environmental goals? A preliminary assessment of ‘green fintech’ and ‘sustainable digital finance’. Eur. Co. Financ. Law Rev. 2022, 19, 128–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Khan, V.M. Blockchain and energy commodity markets: Legal issues and impact on sustainability. J. World Energy Law Bus. 2021, 15, 462–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rank | GF/ESG | FinTech | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Words | Occurrences | Words | Occurrences | |

| 1 | ESG | 345 | Fintech/Financial technology | 420 |

| 2 | Corporate social responsibility | 187 | Blockchain | 48 |

| 3 | Environmental | 141 | Banking/bank | 42 |

| 4 | Sustainability | 139 | Cryptocurrency | 41 |

| 5 | Green finance | 104 | COVID-19 | 35 |

| 6 | Social | 87 | Peer-to-peer lending | 32 |

| 7 | Corporate governance | 76 | Financial | 28 |

| 8 | Sustainable development | 64 | Innovation | 28 |

| 9 | Performance | 63 | Artificial intelligence | 26 |

| 10 | COVID-19 | 61 | Bitcoin | 26 |

| 11 | Governance | 55 | China | 23 |

| 12 | Disclosure | 48 | Machine learning | 21 |

| 13 | ESG investing | 47 | Risk | 21 |

| 14 | ESG performance | 44 | Technology | 21 |

| 15 | Financial performance | 44 | Trust | 21 |

| 16 | Sustainable finance | 39 | Crowdfunding | 19 |

| 17 | Climate change | 37 | Finance | 17 |

| 18 | ESG disclosure | 31 | Finance literacy | 17 |

| 19 | Sustainable reporting | 31 | Digital finance | 16 |

| 20 | Green bonds | 30 | Regulation | 16 |

| Cluster 1: Investments | Cluster 2: Sustainability | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Node | Betweenness | Closeness | PageRank | Node | Betweenness | Closeness | PageRank |

| ESG | 390.4778 | 0.0189 | 0.1181 | Environmental | 95.2308 | 0.0159 | 0.0710 |

| COVID-19 | 6.4613 | 0.0125 | 0.0220 | Social | 38.3138 | 0.0145 | 0.0535 |

| Corporate sustainability | 1.9482 | 0.0114 | 0.0085 | Governance | 13.8548 | 0.0128 | 0.0316 |

| CSR | 1.7344 | 0.0122 | 0.0214 | Environment | 3.5325 | 0.0116 | 0.0123 |

| ESG ratings | 0.6194 | 0.0105 | 0.0067 | Corporate | 3.3053 | 0.0120 | 0.0157 |

| SRI | 0.4496 | 0.0115 | 0.0109 | Corporate social responsibility (CSR) | 0.6084 | 0.0111 | 0.0108 |

| Socially responsible investing | 0.4291 | 0.0111 | 0.0107 | Social and governance (ESG) | 0.0656 | 0.0102 | 0.0081 |

| Sustainable investing | 0.3924 | 0.0110 | 0.0094 | Social responsibility | 0.0370 | 0.0112 | 0.0087 |

| ESG investing | 0.1961 | 0.0108 | 0.0064 | ||||

| Firm performance | 0.1759 | 0.0105 | 0.0065 | ||||

| Socially responsible investment | 0.1228 | 0.0110 | 0.0071 | ||||

| Cluster 3: Reporting and Disclosure | Cluster 4: Impact | ||||||

| Node | Betweenness | Closeness | PageRank | Node | Betweenness | Closeness | PageRank |

| Sustainability | 161.7776 | 0.0179 | 0.0714 | Sustainable development | 16.3449 | 0.0135 | 0.0286 |

| Corporate social responsibility | 46.3065 | 0.0156 | 0.0539 | Green finance | 11.4905 | 0.0123 | 0.0281 |

| Corporate governance | 20.1194 | 0.0137 | 0.0336 | Sustainable | 6.7047 | 0.0127 | 0.0211 |

| Financial performance | 13.3094 | 0.0125 | 0.0213 | Finance | 3.9755 | 0.0119 | 0.0160 |

| Performance | 8.9259 | 0.0128 | 0.0311 | Sustainable finance | 3.3061 | 0.0125 | 0.0193 |

| Environmental performance | 2.0024 | 0.0112 | 0.0104 | Climate change | 2.6360 | 0.0118 | 0.0143 |

| ESG performance | 1.8596 | 0.0120 | 0.0142 | Investment | 2.4620 | 0.0115 | 0.0121 |

| Sustainability reporting | 1.2672 | 0.0120 | 0.0135 | Green bonds | 2.2689 | 0.0112 | 0.0144 |

| Disclosure | 1.1188 | 0.0120 | 0.0187 | Stakeholder engagement | 1.6554 | 0.0119 | 0.0138 |

| Financial | 0.9488 | 0.0116 | 0.0125 | Development | 0.5606 | 0.0115 | 0.0114 |

| Integrated reporting | 0.8886 | 0.0119 | 0.0111 | Green | 0.5518 | 0.0108 | 0.0101 |

| ESG disclosure | 0.6497 | 0.0116 | 0.0107 | China | 0.0457 | 0.0110 | 0.0090 |

| Corporate social | 0.5848 | 0.0115 | 0.0116 | Innovation | 0.0224 | 0.0114 | 0.0087 |

| Reporting | 0.1393 | 0.0115 | 0.0103 | ||||

| Firm value | 0.1087 | 0.0112 | 0.0086 | ||||

| Stakeholder theory | 0.0138 | 0.0112 | 0.0099 | ||||

| Responsibility | 0 | 0.0110 | 0.0108 | ||||

| Cluster 1: Applications | Cluster 2: Digital Assets | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Node | Betweenness | Closeness | PageRank | Node | Betweenness | Closeness | PageRank |

| Fintech | 992.3421 | 0.0208 | 0.2824 | Blockchain | 8.7153 | 0.0128 | 0.0521 |

| Financial technology | 4.5165 | 0.0123 | 0.0373 | Bitcoin | 0.5023 | 0.0111 | 0.0267 |

| Financial inclusion | 2.8678 | 0.0119 | 0.0324 | Cryptocurrency | 0.2789 | 0.0111 | 0.0245 |

| Banking | 1.8884 | 0.0116 | 0.0246 | Cryptocurrencies | 0 | 0.0108 | 0.0136 |

| Financial | 1.5491 | 0.0112 | 0.0187 | Information asymmetry | 0 | 0.0108 | 0.0100 |

| Innovation | 1.5478 | 0.0116 | 0.0213 | Cluster 3: Artificial Intelligence and Data Analytics | |||

| COVID-19 | 1.4451 | 0.0115 | 0.0252 | Node | Betweenness | Closeness | PageRank |

| Risk | 1.1550 | 0.0112 | 0.0186 | Financial services | 0.8462 | 0.0114 | 0.0190 |

| Regulation | 0.7519 | 0.0111 | 0.0177 | Artificial intelligence | 0.7923 | 0.0112 | 0.0243 |

| Digital finance | 0.6495 | 0.0112 | 0.0166 | Machine learning | 0.5711 | 0.0112 | 0.0215 |

| Technology | 0.4260 | 0.0114 | 0.0156 | Finance | 0.2436 | 0.0112 | 0.0146 |

| Digital | 0.2827 | 0.0111 | 0.0118 | Big data | 0.0657 | 0.0109 | 0.0135 |

| Financial literacy | 0.1648 | 0.0110 | 0.0122 | Cluster 4: Innovations | |||

| Digitalization | 0.1294 | 0.0109 | 0.0115 | Node | Betweenness | Closeness | PageRank |

| P2P lending | 0.0781 | 0.0109 | 0.0133 | Crowdfunding | 1.1920 | 0.0114 | 0.0232 |

| Financial stability | 0.0483 | 0.0109 | 0.0099 | Financial innovation | 0.0118 | 0.0108 | 0.0085 |

| China | 0.0379 | 0.0109 | 0.0133 | Entrepreneurial finance | 0 | 0.0108 | 0.0107 |

| Financial institutions | 0.0313 | 0.0108 | 0.0083 | Cluster 5: Financial Institutions and Markets | |||

| Trust | 0.0280 | 0.0110 | 0.0123 | Node | Betweenness | Closeness | PageRank |

| Peer-to-peer lending | 0.0272 | 0.0109 | 0.0124 | Competition | 0.7790 | 0.0111 | 0.0136 |

| Financial development | 0 | 0.0108 | 0.0080 | Performance | 0.5000 | 0.0108 | 0.0094 |

| Risk management | 0 | 0.0108 | 0.0067 | Islamic banks | 0.2500 | 0.0108 | 0.0082 |

| Management | 0 | 0.0106 | 0.0060 | Bank | 0.1716 | 0.0109 | 0.0103 |

| Digital financial inclusion | 0 | 0.0106 | 0.0053 | Financial market | 0.0652 | 0.0109 | 0.0094 |

| Banks | 0 | 0.0105 | 0.0080 | Indonesia | 0 | 0.0106 | 0.0068 |

| Entrepreneurship | 0 | 0.0105 | 0.0074 | ||||

| Corporate governance | 0 | 0.0105 | 0.0047 | ||||

| Commercial banks | 0 | 0.0105 | 0.0042 | ||||

| Credit risk | 0 | 0.0105 | 0.0042 | ||||

| GF/ESG | Fintech | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Country | Articles | Country | Articles |

| 1 | Canada | 232 | China | 205 |

| 2 | USA | 221 | USA | 132 |

| 3 | China | 171 | United Kingdom | 50 |

| 4 | United Kingdom | 108 | Indonesia | 45 |

| 5 | France | 106 | Italy | 31 |

| 6 | Italy | 103 | Germany | 29 |

| 7 | Australia | 68 | India | 27 |

| 8 | Germany | 63 | Malaysia | 26 |

| 9 | India | 61 | France | 24 |

| 10 | Spain | 45 | Australia | 21 |

| 11 | Japan | 31 | Korea | 20 |

| 12 | Malaysia | 27 | Poland | 19 |

| 13 | Korea | 23 | Vietnam | 19 |

| 14 | Netherlands | 21 | Ukraine | 17 |

| 15 | Vietnam | 19 | Finland | 12 |

| 16 | Sweden | 18 | South Africa | 12 |

| 17 | Switzerland | 15 | Canada | 11 |

| 18 | United Arab of Emirates | 15 | Switzerland | 10 |

| 19 | Pakistan | 14 | Nigeria | 8 |

| 20 | Poland | 14 | Japan | 7 |

| Author(s) (Year) | Journal | DOI |

|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | ||

| Dhaliwal et al. (2011) [73] | The Accounting Review | 10.2308/accr.00000005 |

| Dhaliwal et al. (2012) [74] | The Accounting Review | 10.2308/accr-10218 |

| Donaldson and Preston (1995) [75] | Academy of Management Review | 10.5465/amr.1995.9503271992 |

| Eccles et al. (2011) [76] | Journal of Applied Corporate Finance | 10.1111/j.1745-6622.2011.00357.x |

| Eccles et al. (2014) [77] | Management Science | 10.1287/mnsc.2014.1984 |

| Fatemi et al. (2018) [31] | Global Finance Journal | 10.1016/j.gfj.2017.03.001 |

| Friedman (1970) [78] | The New York Times Magazine | |

| Galbreath (2013) [35] | Journal of Business Ethics | 10.1007/s10551-012-1607-9 |

| Griffin and Mahon (1997) [79] | Business and Society | 10.1177/000765039703600102 |

| Healy and Palepu (2001) [80] | Journal of Accounting and Economics | 10.1016/s0165-4101(01)00018-0 |

| Hillman and Keim (2001) [81] | Strategic Management Journal | 10.1002/1097-0266(200101)22:2%3C125::AID-SMJ150%3E3.0.CO;2-H |

| Ioannou and Serafeim (2012) [82] | Journal of International Business Studies | 10.1057/jibs.2012.26 |

| Jensen and Meckling (1976) [83] | Journal of Financial Economics | 10.1016/0304-405x(76)90026-x |

| Jo and Harjoto (2011) [84] | Journal of Business Ethics | 10.1007/s10551-011-0869-y |

| Margolis and Walsh (2003) [85] | Administrative Science Quarterly | 10.2307/3556659 |

| Mcwilliams and Siegel (2000) [86] | Strategic Management Journal | 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200005)21:5<603::AID-SMJ101>3.0.CO;2-3 |

| Mcwilliams and Siegel (2001) [87] | Academy of Management Review | 10.5465/amr.2001.4011987 |

| Orlitzky et al. (2003) [88] | Organizational Studies | 10.1177/0170840603024003910 |

| Porter and Kramer (2006) [89] | Harvard Business Review | |

| Suchman (1995) [90] | Academy of Management Review | 10.2307/258788 |

| Waddock and Graves (1997) [91] | Strategic Management Journal | 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199704)18:4<303::AID-SMJ869>3.0.CO;2-G |

| Cluster 2 | ||

| Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim (2018) [32] | Financial Analysts Journal | 10.2469/faj.v74.n3.2 |

| Barnett and Salomon (2006) [92] | Strategic Management Journal | 10.1002/smj.557 |

| Bauer et al. (2005) [93] | Journal of Banking and Finance | 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2004.06.035 |

| Carhart (1997) [94] | Journal of Finance | 10.2307/2329556 |

| Derwall et al. (2005) [95] | Financial Analysts Journal | 10.2469/faj.v61.n2.2716 |

| Dimson and Karakas (2015) [96] | The Review of Financial Studies | 10.1093/rfs/hhv044 |

| Edmans (2011) [97] | Journal of Financial Economics | 10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.03.021 |

| Fama and French (1992) [98] | Journal of Finance | 10.2307/2329112 |

| Fama and French (1993) [99] | Journal of Financial Economics | 10.1016/0304-405x(93)90023-5 |

| Fama and French (2015) [100] | Journal of Financial Economics | 10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.10.010 |

| Friede et al. (2015) [101] | Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment | 10.1080/20430795.2015.1118917 |

| Galema et al. (2008) [102] | Journal of Banking and Finance | 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2008.06.002 |

| Heinkel et al. (2001) [103] | Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis | 10.2307/2676219 |

| Hong and Kacperczyk (2009) [104] | Journal of Financial Economics | 10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.09.001 |

| Khan et al. (2016) [105] | The Accounting Review | 10.2308/accr-51383 |

| Nofsinger and Varma (2014) [33] | Journal of Banking and Finance | 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.12.016 |

| Renneboog et al. (2008) [106] | Journal of Banking and Finance | 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2007.12.039 |

| Statman and Glushkov (2009) [107] | Financial Analysts Journal | 10.2469/faj.v65.n4.5 |

| Van Duuren et al. (2016) [47] | Journal of Business Ethics | 10.1007/s10551-015-2610-8 |

| Cluster 3 | ||

| Benabou and Tirole (2010) [108] | Economica | 10.1111/j.1468-0335.2009.00843.x |

| Chatterji et al. (2009) [109] | Journal of Economics and Management Strategy | 10.1111/j.1530-9134.2009.00210.x |

| El Ghoul et al. (2011) [110] | Journal of Banking and Finance | 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2011.02.007 |

| Ferrell et al. (2016) [111] | Journal of Financial Economics | 10.1016/j.jfineco.2015.12.003 |

| Godfrey et al. (2009) [112] | Strategic Management Journal | 10.1002/smj.750 |

| Goss and Roberts (2011) [113] | Journal of Banking and Finance | 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.12.002 |

| Kruger (2015) [114] | Journal of Financial Economics | 10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.09.008 |

| Lins et al. (2017) [115] | The Journal of Finance | 10.1111/jofi.12505 |

| Servaes and Tamayo (2013) [116] | Management Science | 10.1287/mnsc.1120.1630 |

| Sharfman and Femando (2008) [117] | Strategic Management Journal | 10.1002/smj.678 |

| Author(s) (Year) | Journal | DOI |

|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | ||

| Gomber et al. (2018) [118] | Journal of Management Information Systems | 10.1080/07421222.2018.1440766 |

| Haddad and Hornuf (2019) [119] | Small Business Economics | 10.1007/s11187-018-9991-x |

| Lee and Shin (2018) [120] | Business Horizons | 10.1016/j.bushor.2017.09.003 |

| Cluster 2 | ||

| Nakamoto, S. (2008) [121] | Bitcoin | |

| Cluster 3 | ||

| Buchak et al. (2018) [40] | Journal of Financial Economics | 10.1016/j.jfineco.2018.03.011 |

| Lin et al. (2013) [122] | Management Science | 10.1287/mnsc.1120.1560 |

| Cluster 4 | ||

| Davis (1989) [123] | MIS Quarterly | 10.2307/249008 |

| Fornell and Larcker (1981) [124] | Journal of Marketing Research | 10.2307/3151312 |

| Journals | Articles Published | ABDC | ABS | SJR | Year of the 1st Volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Finance | 75 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2019 |

| Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment | 74 | N/A | 1 | Q1 | 2011 |

| Business Strategy and the Environment | 72 | A | 3 | Q1 | 1992 |

| Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | 60 | C | 1 | Q1 | 1993 |

| Finance Research Letters | 58 | A | 2 | Q1 | 2004 |

| Journal of Business Ethics | 40 | A | 3 | Q1 | 1982 |

| Journal of Portfolio Management | 40 | A | 3 | Q1 | 1974 |

| Journal of Business Research | 28 | A | 3 | Q1 | 1973 |

| Journal of Risk and Financial Management | 22 | B | N/A | N/A | 2008 |

| Sustainability Accounting Management and Policy Journal | 20 | B | 2 | Q1 | 2010 |

| Journals | Articles Published | ABDC | ABS | SJR | Year of the 1st Volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finance Research Letters | 35 | A | 2 | Q1 | 2004 |

| Journal of Risk and Financial Management | 27 | B | N/A | N/A | 2008 |

| Review of Financial Studies | 18 | A * | 4 * | Q1 | 1988 |

| Pacific-Basin Finance Journal | 16 | A | 2 | Q1 | 1993 |

| Research in International Business and Finance | 16 | B | 2 | Q1 | 2004 |

| International Journal of Bank Marketing | 14 | A | 1 | Q2 | 1983 |

| International Review of Financial Analysis | 14 | A | 3 | Q1 | 1992 |

| European Journal of Finance | 13 | A | 3 | Q1 | 1995 |

| Journal of Asian Finance Economics and Business | 13 | N/A | N/A | Q2 (2020) | 2014 |

| Electronic Commerce Research | 12 | A | 2 | Q1 | 2001 |

| Author(s)/Year | Journal | Title |

|---|---|---|

| Wan, Qian, and Yu (2022) [125] | Journal of Sensors | Analysis of Green Financial Policy Utility: A Policy Incentive Financial Mechanism Based on State Space Model Theory Algorithm |

| Wang (2022) [126] | Managerial and Decision Economics | Research on the Impact Mechanism of Green Finance on the Green Innovation Performance of China’s Manufacturing Industry |

| Puschmann, Hoffmann, and Khmarskyi (2020) [127] | Sustainability | How Green FinTech Can Alleviate the Impact of Climate Change: The Case of Switzerland |

| Macchiavello and Siri (2022) [128] | European Company and Financial Law Review | Sustainable Finance and Fintech: Can Technology Contribute to Achieving Environmental Goals? A Preliminary Assessment of ‘Green Fintech’ and ‘Sustainable Digital Finance’ |

| Lee and Khan (2022) [129] | Journal of World Energy Law and Business | Blockchain and Energy Commodity Markets: Legal Issues and Impact on Sustainability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwong, R.; Kwok, M.L.J.; Wong, H.S.M. Green FinTech Innovation as a Future Research Direction: A Bibliometric Analysis on Green Finance and FinTech. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014683

Kwong R, Kwok MLJ, Wong HSM. Green FinTech Innovation as a Future Research Direction: A Bibliometric Analysis on Green Finance and FinTech. Sustainability. 2023; 15(20):14683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014683

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwong, Raymond, Man Lung Jonathan Kwok, and Helen S. M. Wong. 2023. "Green FinTech Innovation as a Future Research Direction: A Bibliometric Analysis on Green Finance and FinTech" Sustainability 15, no. 20: 14683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014683