Abstract

Optimizing the interaction between individuals and their work environment has become increasingly relevant in enhancing employee well-being and driving the overall success of businesses. The goal of this study is to provide information about how ergonomics affects job performance in the tourism and hospitality industry. The full-time staff employees of Egypt’s category (A) travel agencies and five-star hotels were the source of the study’s data. The partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) technique of analysis was utilized to explore how ergonomics influences job performance while taking into account the mediating roles of work engagement and talent retention. WarpPLS statistical software version 7.0 was used to analyze the 389 valid replies obtained. The findings revealed that there is a positive relationship between the employees’ perception of ergonomics on their job performance, in addition to the positive relationships between the perception of ergonomics and work engagement and talent retention. The work engagement and talent retention were also found to have a positive relationship with job performance. Furthermore, research revealed that work engagement and talent retention act as mediators between ergonomics and job performance. The results of this research significantly advance the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model theory. The study also offers evidence-based recommendations to organizations in the tourism and hospitality industry, empowering them to establish supportive work environments that enhance the job performance, work engagement, and talent retention. Businesses in this industry could create work environments that prioritize the well-being, comfort, and safety of their employees by embracing ergonomic concepts.

1. Introduction

In the current dynamic and competitive business environment, the tourism and hospitality industry is experiencing notable growth and change [1]. This has led to a growing recognition of the importance of ergonomics in influencing job performance. Ergonomics, which focuses on optimizing the interaction between individuals and their work environment, has become increasingly relevant in enhancing employee well-being and driving the overall success of businesses in the tourism and hospitality sector [2,3,4]. Dedicating significant importance to ergonomics, organizations recognize its crucial role in influencing employee well-being, performance, and overall operational efficiency [5,6]. Through the incorporation of ergonomic principles into the workplace, organizations prioritize the health and comfort of their workforce, resulting in a wide range of benefits that go beyond mere physical comfort [7,8].

Ergonomic design plays a fundamental role in preventing injuries and discomfort associated with the workplace [9,10]. Well-designed workstations, seating arrangements, and equipment effectively reduce the likelihood of musculoskeletal disorders, repetitive strain injuries, and other physical ailments. This not only protects the physical well-being of employees but also reduces absenteeism and medical expenses, thereby improving organizational productivity [11]. Moreover, ergonomics has a direct impact on job satisfaction and morale. When employees perceive that their organization prioritizes their well-being and comfort, their overall satisfaction with their jobs tends to increase. A comfortable and supportive work environment fosters a positive workplace culture, elevating employee morale and motivation. Consequently, this leads to higher levels of engagement and a willingness to go the extra mile in performing their tasks [12,13]. The influence of ergonomics extends beyond individual well-being and also has implications for organizational performance [14]. By optimizing the work environment through ergonomic design, productivity and efficiency can be enhanced. When employees are provided with well-designed workspaces and tools, they can carry out their tasks more easily and effectively. This efficiency translates into improved organizational performance, resulting in increased output and profitability [7,15].

In the pursuit of excellence, organizations have recognized the significant connection between ergonomics and job performance. This relationship goes beyond physical comfort and encompasses psychological and cognitive aspects that profoundly influence how employees carry out their tasks and contribute to the organization’s objectives [16]. Job performance is no longer viewed as a standalone measure but rather as a complex outcome influenced by multiple factors, including work engagement and talent retention [17,18]. Work engagement plays a vital role in connecting ergonomics with job performance. When employees work in an environment that incorporates ergonomic principles, it can greatly enhance their level of engagement. Engaged employees are more likely to demonstrate greater dedication, creativity, and commitment, which positively impacts their overall job performance [19]. Moreover, the interconnectedness of these factors extends to talent retention, which is a critical concern in industries that face challenges in retaining skilled professionals [20]. Ergonomics, by creating a supportive work environment, contributes to employee satisfaction and well-being, thus influencing their decision to stay with an organization [21]. When employees feel that their comfort and needs are valued, they are more likely to remain dedicated and contribute their skills to the long-term success of the company. Furthermore, in response to the growing recognition of the significance of talent retention, ergonomics has emerged as a strategic tool for retaining employees. A work environment that places a high priority on the comfort and well-being of employees fosters a sense of loyalty and attachment. Employees are more inclined to stay with an organization that values their health and actively endeavors to create an environment that supports their physical and mental needs [22,23].

Although the correlation between ergonomics and job performance has been explored in different industries [16], there is a research gap regarding this relationship specifically within the context of the tourism and hospitality sector, particularly when considering the mediating factors of work engagement and talent retention [24]. The existing literature on ergonomics in this industry primarily concentrates on physical aspects such as the workplace design, equipment, and safety, with limited emphasis on the broader concept of ergonomics and its influence on job performance. There is a research gap in understanding the specific ergonomic factors that have a significant impact on job performance within the tourism and hospitality industry. While studies in other sectors have explored the influence of ergonomics on job performance, the distinctive characteristics of the tourism and hospitality business, such as customer interactions, service quality, and emotional labor, may necessitate a customized approach. Hence, there is a clear need for research that focuses on identifying the specific ergonomic factors that hold the most relevance and influence within the tourism and hospitality industry. Additionally, another research gap lies in understanding the mediating roles of work engagement and talent retention. While previous studies have separately examined the relationship between ergonomics and job performance, as well as the impact of work engagement and talent retention on job performance, no prior research has investigated the mediating effects of work engagement and talent retention in the relationship between ergonomics and job performance specifically within the tourism and hospitality sector. Gaining insight into the interplay of these variables is crucial for obtaining a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms by which ergonomics affects job performance. It is imperative to address these research gaps to advance knowledge in the field of ergonomics and its impact on job performance within the tourism and hospitality sector. By bridging these gaps, researchers can offer evidence-based recommendations to organizations in this industry, empowering them to establish supportive work environments that enhance job performance, work engagement, and talent retention. Consequently, the current study research question is the following: how is job performance affected by ergonomics in the tourism and hospitality industry through work engagement and talent retention?

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Ergonomics

Ergonomics, or human factors, involves applying scientific principles and practices to design work systems, tasks, equipment, and environments that optimize human well-being, comfort, safety, and performance. Its objective is to establish a harmonious alignment between the demands of the work and the capabilities of the individuals carrying out the tasks. By implementing ergonomic practices, organizations can enjoy various advantages, such as enhanced employee well-being, increased productivity, improved job satisfaction, and decreased risks of work-related injuries or illnesses [25,26]. In an organizational context, ergonomics encompasses the evaluation and management of different aspects, including physical ergonomics, cognitive ergonomics, and organizational ergonomics [27,28]. Physical ergonomics specifically concentrates on the design of workstations, tools, equipment, and environments to promote optimal posture, body mechanics, and physical comfort. This involves considerations such as appropriate desk and chair heights, adjustable work surfaces, ergonomic seating, and adequate lighting to minimize the risk of musculoskeletal disorders and fatigue [29]. Cognitive ergonomics focuses on the design of tasks, processes, and interfaces to align with human cognitive abilities, information processing, and decision-making. Its objective is to minimize the mental workload, enhance information presentation and organization, and optimize human–computer interaction. This involves considerations such as user-friendly software interfaces, clear instructions, intuitive workflows, and efficient communication systems [30]. Organizational ergonomics aims to optimize the organizational and social aspects of work to improve employee well-being and performance. It encompasses various factors, including workload management, work schedules, teamwork and collaboration, leadership styles, and organizational culture. By fostering a supportive and inclusive work environment, organizations can mitigate stress, enhance job satisfaction, and promote employee engagement [31,32].

2.2. Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Model

The JD-R (Job Demands-Resources) model is a well-established theoretical framework in occupational psychology that elucidates how job characteristics impact employee well-being and performance. In this model, job demands encompass the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of work that necessitate sustained effort and may result in stress or burnout if not effectively managed. On the other hand, job resources are the elements that facilitate goal attainment, alleviate job demands, and foster motivation and well-being [33,34,35]. Within the realm of ergonomics, the physical and cognitive aspects of work can be categorized as either job demands or resources based on their management. For instance, an ergonomically optimized workstation that encourages correct posture and minimizes physical strain can be considered a job resource. Conversely, an uncomfortable and inadequately designed workstation can be perceived as a job demand [36]. Work engagement refers to a positive motivational state marked by elevated levels of energy, dedication, and absorption in one’s work. It plays a significant role as a mediator in the JD-R (Job Demands-Resources) model, as it represents the motivational mechanism through which job resources impact job performance. Engaged employees are more inclined to invest effort, experience greater job satisfaction, and demonstrate superior performance in their roles [37]. Talent retention refers to an organization’s capacity to retain skilled and talented employees over a sustained period. It is closely intertwined with employee engagement, job satisfaction, and overall organizational performance. Engaged employees who benefit from a positive work environment, including ergonomic support, are more likely to feel valued and satisfied, resulting in heightened loyalty and decreased turnover rates [38,39]. By comprehending and implementing the JD-R (Job Demands-Resources) model within the realm of ergonomics, organizations can establish a virtuous cycle whereby ergonomics positively influences both job demands and resources. This, in turn, leads to heightened work engagement, improved job performance, and enhanced talent retention. The model underscores the significance of offering ergonomic support to employees, as it not only enhances their well-being but also generates positive outcomes throughout the organization [34,40,41].

2.3. Tourism and Hospitality Industry

The tourism and hotel business is a major contributor to global economic growth and job creation. Egypt’s tourism and hospitality sectors, as well as its personnel, should be dedicated to giving visitors high-quality services because these sectors are a significant contributor to the country’s economy [42]. According to research by [43], visitors were pleased with the attentiveness and empathetic nature of staff members in tourism and hospitality businesses. As a result, it is important to give hotel personnel better workplace environment “ergonomics” that improves their work engagement, the retention of talent, and job performance, helping them to provide better services to their customers.

2.4. The Relationship between Ergonomics and Job Performance

The connection between ergonomics and job performance is a vital and complex one, as it involves the intricate interaction between the design of the work environment and employees’ capacity to perform their tasks effectively [44]. Ergonomics, which is the scientific discipline focused on optimizing the workplace to match the abilities and requirements of individuals, exerts a significant influence on various facets of job performance [16]. Ergonomic considerations have a substantial impact on the physical well-being of employees. Thoughtfully designed workspaces, ergonomic chairs, and properly adjusted equipment contribute to physical comfort, reducing the likelihood of discomfort, pain, or physical strain. When employees experience physical comfort, they are better able to maintain focus and concentration on their tasks, leading to enhanced overall job performance [45,46]. Furthermore, ergonomics plays a vital role in mitigating errors and cognitive fatigue. Through the reduction in awkward postures and repetitive movements, ergonomic design minimizes the chances of mistakes that may arise from physical discomfort. Working in ergonomically optimized environments helps employees experience less mental fatigue, leading to enhanced cognitive function. This, in turn, positively impacts decision-making and problem-solving abilities, thereby improving job performance [47,48]. Ergonomics is closely tied to efficiency and productivity in the workplace. Thoughtfully designed ergonomic solutions optimize workflow processes by providing employees with streamlined access to tools, resources, and information. This reduces unnecessary movements and minimizes time wastage. As a result, tasks can be completed more swiftly and efficiently, leading to increased overall productivity and, consequently, improved job performance [49,50,51].

In addition to the physical and cognitive aspects, the connection between ergonomics and job performance encompasses the employees’ health and absenteeism. Inadequate ergonomics can contribute to work-related injuries and health problems, potentially leading to increased absenteeism. Conversely, implementing appropriate ergonomic measures can help mitigate these risks, promoting the employees’ overall health and well-being. By reducing absenteeism, workflow disruptions are minimized, ensuring consistent job performance [52,53]. The long-term effects of working in an ergonomically optimized environment are particularly noteworthy [54]. The reduction in physical strain, fewer injuries, and improved overall well-being contribute to elevated job satisfaction and increased career longevity. Employees who receive physical and emotional support from their organization are more likely to consistently perform at their best, ultimately driving organizational success [55,56]. Building upon this, refs. [16,57] have corroborated the significant and positive impact of ergonomics on job performance. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

Ergonomics significantly and positively affects job performance.

2.5. The Relationship between Ergonomics and Work Engagement

Work engagement pertains to being fully absorbed, enthusiastic, and concentrated on work tasks, accompanied by elevated levels of energy, dedication, and focus [58]. Ergonomics plays a critical role in establishing a work environment that fosters and amplifies work engagement through various means [59]. Ergonomics plays a significant role in fostering employee satisfaction, a vital component of work engagement [60]. When employees perceive that their organization prioritizes their well-being and invests in creating ergonomic workspaces, it enhances their satisfaction and commitment to their work [59,61]. Implementing ergonomic interventions demonstrates that the organization values the health and comfort of its employees, which can result in increased job satisfaction and a sense of being valued. Satisfied employees are more likely to be engaged, motivated, and willing to invest discretionary effort into their work tasks [62,63].

Moreover, organizations can promote work engagement by involving employees in the process of ergonomic design [64]. This approach fosters a sense of autonomy and empowerment, which are key drivers of work engagement. When employees have the opportunity to contribute to the design of their workspaces and tools, they develop a sense of ownership and control over their work environment. This involvement can heighten their level of engagement and commitment to their work, as they perceive themselves as active contributors to the organization’s success [65,66]. Ergonomics plays a pivotal role in enhancing the employees’ focus and concentration, which are vital components of work engagement [24,59]. Organizations can promote sustained attention by providing ergonomic workstations and tools that minimize distractions. For instance, ergonomic chairs and adjustable desks enable employees to find optimal seating positions that reduce discomfort and promote good posture, allowing them to concentrate on their tasks without undue physical strain. This improved focus enables employees to immerse themselves in their work and maintain engagement for extended periods [67,68].

Ergonomics also plays a role in fostering proactive behavior among employees, which is closely associated with work engagement. When employees perceive that their organization prioritizes their well-being and provides them with adequate ergonomic support, they are more likely to take proactive measures to enhance their work environment and optimize their performance [69,70]. This may involve adjusting their workstation, effectively utilizing ergonomic tools, or suggesting improvements to the organization. Proactive behavior demonstrates a higher level of engagement and a willingness to exceed minimum requirements, resulting in increased individual and team performance [71]. It is important to note that the relationship between ergonomics and work engagement is cyclical. Work engagement itself can serve as a motivating factor for employees to prioritize and adhere to ergonomic practices. Engaged employees are more likely to actively seek out ergonomic adjustments to further enhance their work environment, thus reinforcing the positive connection between ergonomics and engagement [59,72,73]. Furthermore, ergonomics enhances the level of work engagement [74]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

Ergonomics significantly and positively affects work engagement.

2.6. The Relationship between Work Engagement and Job Performance

The connection between work engagement and job performance is a vital factor that determines how the employees’ emotional commitment to their work translates into tangible outcomes [75]. Work engagement, characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption in tasks, significantly influences different aspects of job performance [76,77]. Work engagement is closely linked to heightened levels of motivation and the effort exerted by employees [78]. Engaged employees demonstrate a strong sense of enthusiasm and dedication towards their work. This intrinsic motivation drives them to invest additional effort in their tasks, resulting in increased productivity and efficiency. Engaged employees are more inclined to exceed their job requirements, ultimately contributing to enhanced job performance [19,79,80]. Work engagement is strongly correlated with the quality of work performed. Engaged employees are fully absorbed in their tasks and exhibit a high level of concentration and focus. This heightened attention to detail leads to a decrease in errors and an improvement in the accuracy of their work. Consequently, the quality of outputs and deliverables tends to be higher among engaged individuals, which has a positive impact on the overall job performance [81,82]. Furthermore, work engagement plays a significant role in fostering the employees’ adaptability and their willingness to embrace challenges. Engaged individuals are more inclined to perceive setbacks as opportunities for growth and learning. Their proactive problem-solving approach and resilience in the face of challenges enable them to navigate uncertainties and complexities more effectively. This adaptability directly translates into improved job performance, especially in dynamic and rapidly changing environments [83,84,85].

Work engagement has a significant impact on interpersonal dynamics and teamwork [86]. Engaged employees typically possess a positive attitude and a willingness to collaborate with their colleagues. This cooperative spirit fosters effective teamwork, communication, and knowledge sharing, leading to a harmonious work environment and improved collective job performance [87,88,89]. Additionally, studies by [90] have shown a positive correlation between work engagement and employee performance. Therefore, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H3.

Work engagement has a significant and positive impact on job performance.

2.7. The Mediating Role of Work Engagement in the Link between Ergonomics and Job Performance

The mediating role of work engagement indicates that the positive impact of ergonomics on job performance is transmitted through the level of work engagement experienced by employees. In essence, work engagement acts as a mechanism that explains how ergonomics influences job performance. By optimizing the work environment to align with the employees’ needs, ergonomics indirectly affects job performance by influencing work engagement [74,91]. Working in an ergonomic environment provides employees with physical comfort, reduced strain, and improved well-being [56]. These factors contribute to a sense of physical ease that can have a positive impact on their psychological state [92]. Engaged employees are more likely to experience positive emotions, higher levels of job satisfaction, and a sense of fulfillment in their work. Moreover, engaged employees are more inclined to fully utilize their skills and competencies, display proactive behavior, and demonstrate a willingness to exceed the minimum requirements of their roles. They exhibit enhanced focus, productivity, and effectiveness in their work tasks, resulting in improved job performance outcomes [93,94].

As a result of the positive psychological state fostered by ergonomics, work engagement is increased. When employees feel physically comfortable and supported by their ergonomic environment, they are more likely to become fully absorbed in their tasks, exhibit higher levels of concentration, and experience a greater sense of dedication and enthusiasm. This heightened work engagement motivates them to invest their time and effort into their work, leading to improved job performance [95,96,97]. Additionally, work engagement can also influence other psychological processes that contribute to job performance, such as cognitive flexibility, problem-solving abilities, and adaptability. Engaged employees are more likely to possess these qualities, which significantly contribute to their overall job performance [98]. It is important to note that work engagement also influences the employees’ willingness to invest discretionary effort and surpass performance expectations [99]. Engaged employees are more inclined to go above and beyond their required duties, fostering innovative thinking, problem-solving skills, and improved task outcomes. The intrinsic motivation generated by ergonomic support aligns with the proactive behavior associated with heightened work engagement, ultimately leading to enhanced job performance. Therefore, the following hypothesis is assumed:

H4.

Work engagement mediates the link between ergonomics and job performance.

2.8. The Relationship between Ergonomics and Talent Retention

Creating a conducive and comfortable work environment through ergonomics is instrumental to talent retention [100,101]. The organizations that prioritize ergonomics demonstrate their commitment to the well-being and satisfaction of employees. This fosters a positive work experience, which contributes to higher levels of talent retention [25,102]. Ergonomics interventions aim to reduce physical discomfort, minimize work-related injuries, and promote overall well-being. When employees work in an environment that supports their physical health and comfort, they experience increased job satisfaction [25,103]. Creating comfortable workstations, providing ergonomic seating, and ensuring proper lighting are factors that contribute to a more positive and enjoyable work experience. When employees feel physically comfortable, they are more likely to experience higher levels of job satisfaction, which in turn leads to increased loyalty and a greater inclination to stay with the organization [104,105].

By prioritizing ergonomics, organizations send a clear message to its employees that their well-being is highly valued and that the organization genuinely cares about their health and safety. This commitment to employee welfare contributes to the development of a positive organizational culture [14,25]. Employees who perceive their organization as caring and supportive are more likely to experience higher levels of job satisfaction, engagement, and loyalty [106]. A positive organizational culture, established on the foundation of ergonomics, fosters a sense of belonging and cultivates long-term employee commitment, ultimately reducing turnover rates [107,108]. Ergonomics interventions have a significant impact on promoting a healthy work–life balance. Through the provision of ergonomic tools, flexible work arrangements, and supportive policies, organizations empower employees to effectively manage their work responsibilities alongside personal commitments [109,110]. This balance between work and personal life is highly valued by employees and contributes to their overall satisfaction and well-being. When employees feel that their organization supports their work–life balance, they are more likely to exhibit a long-term commitment to the company [111,112].

Ergonomics interventions can also serve as a catalyst for talent development and growth within organizations. When employees work in an ergonomic environment, they are better able to concentrate on their tasks, improve their productivity, and foster the development of their skills. The absence of physical discomfort and distractions enables employees to allocate their time and energy toward professional growth and development. By investing in ergonomics, organizations demonstrate their commitment to nurturing employee development, which can result in higher levels of talent retention as employees perceive opportunities for advancement and career growth [113,114,115]. Thus, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H5.

Ergonomics significantly and positively affects talent retention.

2.9. The Relationship between Talent Retention and Job Performance

When an organization prioritizes talent retention, it implements strategies and practices designed to attract, develop, and retain high-performing employees [116,117]. By retaining talented individuals, organizations can maintain a skilled and experienced workforce, which has a positive impact on job performance. Satisfied and committed employees are more likely to demonstrate higher levels of engagement, productivity, and dedication to their work [118,119]. Talent retention plays a significant role in cultivating loyalty and motivation among employees. When employees feel appreciated and acknowledged for their contributions, they are more inclined to exceed the expectations of their job roles. The knowledge that their efforts are recognized and rewarded serves as a strong motivator. This heightened motivation directly translates into improved job performance, resulting in increased productivity levels and favorable outcomes for the organization [120,121,122]. Moreover, talent retention plays a pivotal role in fostering a positive work culture. When employees feel that their skills are valued and they have opportunities for growth and advancement within the organization, they are more inclined to remain committed and engaged. A positive work culture promotes collaboration, teamwork, and the sharing of knowledge, all of which contribute to improved job performance. Employees are more likely to support and assist one another, leading to increased efficiency and effectiveness in achieving organizational objectives [123,124].

Talent retention has a crucial impact on knowledge management within organizations [125]. Experienced and knowledgeable employees have valuable expertise that is developed over time [126]. When these employees are retained, they can actively share their knowledge, mentor others, and contribute to the continuous learning and enhancement of the organization. This transfer and retention of knowledge has a positive influence on job performance by preserving and effectively utilizing critical institutional knowledge [127,128]. Furthermore, talent retention plays a crucial role in ensuring organizational stability and reducing disruptions in workflow. When employees remain with an organization for a longer duration, they develop a profound understanding of its processes, systems, and culture. This institutional knowledge facilitates smoother operations, faster decision-making, and improved coordination among team members. It also reduces the time and resources needed for onboarding and training new employees, enabling the organization to maintain consistent performance levels and efficiently meet business objectives [129,130]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6.

Talent retention significantly and positively affects job performance.

2.10. The Mediating Role of Talent Retention in the Link between Ergonomics and Job Performance

Studies have demonstrated that a carefully designed ergonomic environment can yield favorable effects on job performance by alleviating physical discomfort, minimizing work-related injuries, and enhancing overall well-being [56]. Additionally, talent retention is influenced by multiple factors, including job satisfaction, organizational culture, career development opportunities, and compensation. The retention of skilled employees holds significant importance for organizational success as it guarantees the continuity of critical skills, knowledge, and experience within the workforce [122,131]. The relationship between ergonomics and job performance can be mediated by talent retention. When organizations prioritize ergonomics and establish a comfortable work environment, it positively impacts employee satisfaction, well-being, and engagement. Employees who experience physical comfort and reduced strain are more likely to be satisfied with their jobs, which, in turn, increases their commitment and loyalty [59,132]. This heightened job satisfaction and commitment, in return, contribute to talent retention within the organization. Satisfied employees who perceive organizational support and a positive work environment are more inclined to remain with the company, resulting in reduced turnover rates. Talent retention enables organizations to retain a skilled workforce that possesses valuable knowledge of the organization’s processes, systems, and industry-specific expertise [42,113].

Through effective implementation of ergonomics interventions, organizations can decrease turnover rates and retain skilled employees who have acquired extensive knowledge and expertise over time. This accumulated knowledge and expertise positively impact job performance by enhancing the productivity, problem-solving abilities, and overall efficiency [133,134]. Additionally, talent retention also plays a crucial role in sustaining the long-term benefits of ergonomics within the organization. Talent retention enables organizations to cultivate a culture of continuous improvement and innovation. Skilled employees, who possess a deep understanding of ergonomic practices and their advantages, can offer valuable insights and contribute to the ongoing enhancement of the work environment [135,136]. This continual improvement in ergonomics further enhances job performance by creating an environment that adapts to the evolving needs and demands of employees [137]. In addition, talent retention is in line with an organization’s dedication to fostering a learning culture [138,139]. When employees stay with the organization for extended periods, they have ongoing opportunities to enhance their skills and knowledge. Organizations that prioritize talent retention also typically invest in continuous training and development, equipping their employees with the necessary resources to excel. This culture of continuous learning directly contributes to improved job performance, as employees possess the skills and knowledge needed to adapt to evolving business demands [140,141]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is postulated:

H7.

Talent retention mediates the link between ergonomics and job performance.

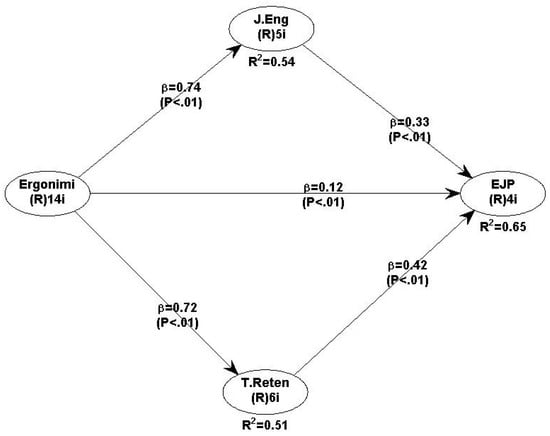

The hypothesized research framework presented in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

The hypothesized research framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measures and Instrument Development

Ergonomics was assessed by a 14-item scale adapted from [142]. Sample items include: “Reaching or working over your head or away from your body” and “Insufficient breaks or pauses during the workday”. In addition, employee job performance was measured by a 4-item scale from [143]. For example, “I make sure that my work meets/exceeds performance standards” and “I meet/exceed my goals”. Moreover, work engagement was evaluated by a 5-item scale from [144]. For instance, “I am highly engaged in this work” and “Sometimes I am so into my work that I lose track of time”. Furthermore, talent retention was determined by a 6-item scale adapted from [145]. For example, “My hotel/travel agency provides career development opportunities to retain key employees” and “Attractive compensation and benefit incentives engage me to work with my hotel/travel agency”. The entire scale items are included in Appendix A. This study used a self-administrated questionnaire. The survey was divided into two parts. The first part included 29 items to examine the study’s four latent variables: ergonomics, employee job performance, work engagement, and talent retention. All responses were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale, “ranging from 1 for strongly disagrees to 5 for strongly agrees”. The second part included five questions regarding employees’ gender, age, educational level, years of work experience, and work organization. The original questionnaire was written in English. Then, to guarantee that the matching was accomplished, a back translation technique was used.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

Information collected from the entry and middle levels employees of Egypt’s category (A) travel agencies “In Egypt, there are three types of travel agents (A–C)” and five-star hotels between March 2023 and April 2023 was used to evaluate the study’s proposed model. Since they aim to consistently provide superior services to their customers, working at a category (A) travel agency or a five-star hotel is demanding. The high workload and demands of the jobs in those organizations are more likely to make ergonomics, work engagement, and talent retention among the critical factors for effective job performance. According to [146]’s statistics, there are 158 five-star hotels and 2222 category (A) travel agencies operating in Egypt. However, no official figures are available for Egypt that include the full number of personnel employed by category A travel agencies or five-star hotels. Therefore, this study relied on [147]’s sampling equation. Cochran [147] developed an equation to produce a representative sample for the population that equals 385 replies in situations when a list of the population is not available, as in the case of the current study. The convenience sampling approach was used in the current study because of the geographical scope and the fact that the five-star hotels and category (A) travel agencies were spread out over the country. A total of 600 questionnaires were given out to the organizations under examination. Only 389 valid forms were retrieved, resulting in a 64.8% response rate: 266 (68.4%) surveys were collected from 25 five-star hotels, and 123 (31.6%) responses were collected from 45 categories-A travel agencies. For the analysis, the 389 valid responses that were obtained were sufficient.

3.3. Data Analysis

PLS-SEM is a popular analytical technique in tourism and hospitality research, e.g., Hair et al. [148]. It is a useful technique for analyzing complicated structural models that connect several variables via both indirect and direct paths [149].

4. Results

4.1. Participants’ Profile

Accordng to Table 1, out of the 389 total participants, 314 (80.7%) were male and 75 (19.3%) were female. Also, 51 (13.1%) participants were beyond the age of 50, 187 (48.1%) participants were between the ages of 30 and less than 40, and 151 (38.8%) participants were below the age of 30. Moreover, 63 (16.2%) had a high school or institute certificate, 313 (80.5%) had a bachelor’s degree, and 13 (3.3%) held a master’s or a PhD. Furthermore, 173 (44.5%) of the participants had more than ten years of work experience, while 73 (18.8%), 78 (20.1%), and 65 (16.7%) had less than two years’, two to five years’, and six to ten years’ experience, respectively. Additionally, 266 participants (68.4%) worked in five-star hotels, as opposed to 123 participants (31.6%) who worked in category (A) travel agencies.

Table 1.

Participant’s profile (N = 389).

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Factor Loadings

After factor loading was calculated, the item loadings were found to range from 0.501 to 0.987 (see Table 2). An item loading value greater than 0.5 can be regarded as acceptable by [148]’s guideline. The mean scores of the employees’ perceptions of the studied variables are shown in Table 2. The values were (3.34 ± 1.03), (3.16 ± 0.96), (3.47 ± 0.95), and (2.84 ± 1.04) for ergonomics, job performance, work engagement, and talent retention, respectively.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and factor loadings.

4.3. Reliability and Validity

Manley et al. [149] claimed that when all variables have values greater than 0.7, as indicated in Table 3, Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability for all variables are then considered sufficient. Furthermore, AVE values greater than 0.5 were observed, proving the validity of the scales according to [148]’s standard. The findings of the full collinearity VIF were all sufficient as well.

Table 3.

Reliability and AVEs.

In addition, a discriminant validity test was performed. Table 4 demonstrates that the AVE value for each variable is bigger than the greatest common value. These findings confirm the study model’s reliability and validity, according to [148]. The HTMT for validity was also examined (see Table 5), illustrating that it is sufficient for all values as they all were <0.85.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity results.

Table 5.

HTMT for validity.

4.4. Model Fit and Quality Indices for the Research Model

The model fit had been examined before testing the study’s hypotheses. The results for model fit and quality indices were in line with the standards, as presented in Appendix B.

4.5. The Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

The path coefficient analysis (β), p-value, and R-square (R2) were used to examine the hypothesized structural model of the current study. The results of the hypotheses’ testing (Figure 2 and Table 6) indicated that there is a positive relationship between ergonomics and job performance (β = 0.12, p < 0.01), work engagement (β = 0.74, p < 0.01), and talent retention (β = 0.72, p < 0.01). This means that ergonomics increases job performance, work engagement, and talent retention. Thus, H1, H2, and H5 are supported. Also, a positive relationship between work engagement and talent retention and job performance existed (β = 0.33, p < 0.01) and (β = 0.42, p < 0.01), respectively. This means that work engagement and talent retention increase job performance. So, H3 and H6 are supported.

Figure 2.

The final model of the study.

Table 6.

Mediation analysis (Bootstrapped Confidence Interval).

In addition, Figure 2 illustrated that ergonomics interpreted 54% of the variance in work engagement (R2 = 0.54) and 51% of the variance in talent retention (R2 = 0.51). Moreover, ergonomics, work engagement, and talent retention explained 65% of the variance in job performance (R2 = 0.65).

Lastly, the indirect impact was measured to evaluate the role of work engagement and talent retention as mediators (see Table 6). For work engagement, the “bootstrapping analysis” indicated that the indirect effect’s Std. β = 0.244 (0.740 × 0.330) was significant, with a t-value of 7.182. In addition, the indirect effect of 0.244, “95% Bootstrapped Confidence Interval” (LL = 0.178, UL = 0.311), does not cross a zero in between, indicating a mediation. Thus, the mediation role of work engagement in the ergonomics–job performance relationship is considered statistically significant. Therefore, H4 is supported.

Furthermore, for talent retention, the “bootstrapping analysis” indicated that the indirect effect’s Std. β = 0.302 (0.720 × 0.420) was significant, with a t-value of 8.894. In addition, the indirect effect of 0.302, “95% Bootstrapped Confidence Interval” (LL = 0.236, UL = 0.369), does not cross a zero in between, indicating a mediation. Thus, the mediation role of talent retention in the ergonomics–job performance relationship is considered statistically significant. Therefore, H7 is supported.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine how job performance is affected by ergonomics, taking into account work engagement and talent retention as mediators. The findings support our first hypothesis that ergonomics significantly and positively affects job performance. This finding is in line with prior research, e.g., refs. [45,46,49,50,51] which claimed that ergonomics increases job performance. Workspaces that are thoughtfully planned, ergonomic seats, and correctly set up equipment all contribute to physical comfort, lowering the risk of discomfort, pain, or physical strain. Physically comfortable employees are better able to focus and concentrate on their jobs, resulting in improved overall job performance [45,46]. Ergonomics is also important in reducing mistakes and cognitive strain. Ergonomic design reduces the risks of mistakes caused by physical pain by reducing uncomfortable postures and repeated activities. Working in ergonomically optimized workplaces reduces mental tiredness, resulting in improved cognitive performance. By viewing employees as the key to guaranteeing company sustainability and working to create meaningful and significant work, businesses acknowledge the relevance of human factors in organizational processes [150,151,152].

The findings also support our second hypothesis that ergonomics significantly and positively affects work engagement. This finding is in line with prior research, e.g., refs. [62,63] which claimed that ergonomics increases work engagement. Employees obtain a sense of ownership and control over their work environment when they have the chance to contribute to the design of their workplaces and equipment. This involvement might increase their level of engagement and passion for their jobs since they consider themselves as active contributors to the success of the organization [65,66]. In addition, the findings support our third hypothesis that work engagement significantly and positively affects job performance. This finding is in line with prior research, e.g., refs. [19,79,80,90] claimed that work engagement increases job performance. Individual and group interactions as well as collaboration are significantly impacted by work engagement. Employees who are engaged often have a good attitude and are eager to cooperate with their coworkers. This cooperative atmosphere promotes successful collaboration, interaction, and information sharing, resulting in a peaceful workplace and increased collective job performance [87,88,89].

Moreover, the findings support our fourth hypothesis that work engagement mediates the link between ergonomics and job performance. This finding indirectly is in line with prior research, e.g., refs. [95,96,97,99]. Employees are more likely to become completely engaged with their work, have better levels of focus, and feel more dedicated and enthusiastic when they feel physically comfortable and encouraged by their ergonomic atmosphere. This increased work engagement inspires employees to devote more time and effort to their jobs, resulting in enhanced performance at work. Furthermore, the findings support our fifth hypothesis that ergonomics affects significantly and positively talent retention. This finding is in line with prior research, e.g., refs. [100,101] which claimed that ergonomics increases talent retention. Interventions in ergonomics may foster talent development and progress inside organizations. Employees who operate in an ergonomic setting are more able to focus on their jobs, increase their productivity, and promote the growth of their talents. Employees may devote their time and efforts to professional development and progress since they are not bothered by physical discomfort or interruptions.

Additionally, the findings support our sixth hypothesis that talent retention significantly and positively affects job performance. This finding is in line with prior research, e.g., refs. [116,117] which claimed that talent retention increases job performance. When workers feel valued and recognized for their achievements, they are more likely to go above and beyond what is required of them in their positions. Knowing that their efforts are recognized and appreciated is a powerful incentive. This increased drive leads to enhanced work performance. Lastly, the findings support our seventh hypothesis that talent retention mediates the link between ergonomics and job performance. This finding is indirectly in line with prior research, e.g., refs. [137,138,139,140,141]. The long-term advantages of ergonomics inside the organization depend critically on retaining talent. Organizations may foster a culture of continual improvement and innovation through the retention of talent. Skilled individuals with a thorough awareness of ergonomic practices and their benefits can provide useful insights and contribute to the continuous improvement of the work environment. This continuous development in ergonomics improves job performance by establishing an environment that responds to the employees’ changing requirements and desires.

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The findings of this study make notable contributions to the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model theory in various meaningful ways. One significant aspect is the contextualization of the JD-R model within the tourism and hospitality industry. By specifically examining this industry, the study acknowledges the distinct demands, challenges, and attributes that shape the connections between job demands, resources, and outcomes. This recognition emphasizes the adaptability and applicability of the JD-R model across diverse work environments. Another valuable contribution of this study is the introduction of ergonomics as a significant job resource within the tourism and hospitality industry. While the JD-R model traditionally focuses on psychological and social resources, the incorporation of ergonomic factors highlights the model’s flexibility in encompassing the physical elements of the work environment. This extension enhances the model’s overall inclusiveness and comprehensiveness. Furthermore, this study expands the JD-R model by incorporating the mediating effects of work engagement and talent retention. While the conventional model primarily focuses on the direct impact of job demands and resources on well-being and performance, this study delves deeper into the underlying mechanisms by exploring how enhanced ergonomics influence work engagement, talent retention, and ultimately, job performance. By considering these mediating factors, the study provides a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships within the JD-R model.

6.2. Practical Implications

The examination of ergonomics and its influence on job performance within the tourism and hospitality industry yields various practical implications, specifically on work engagement and talent retention. The application of ergonomics in the tourism and hospitality industry involves designing work environments, tools, and tasks to align with the capabilities and requirements of employees. By embracing ergonomic principles, businesses in this sector can establish work settings that prioritize the well-being, comfort, and safety of their staff. This approach can result in decreased physical strain, enhanced job satisfaction, and overall improved well-being, all of which have a positive impact on work engagement and job performance. Factors such as ergonomically designed workstations, appropriate lighting, comfortable seating, and streamlined workflows contribute to creating a favorable work environment that fosters engagement, motivation, and productivity.

Human factors and ergonomics are required to be well-understood within the complex systems of today’s work environments [153]. In terms of sustainability and fair labor practices, globalization and the digitalization of value production present serious challenges to today’s businesses. Human factors and ergonomics may be useful in dealing with these challenges [154]. Specifically, regarding ergonomics’ return on investment, investment in ergonomics programs creates annual capital improvements of up to $100,000 per year [155].

Through the optimization of work processes and the mitigation of physical and mental strain, employees can enhance their task performance in terms of efficiency and effectiveness. The implementation of ergonomic interventions, such as the provision of suitable tools and equipment, the establishment of comprehensive training programs, and the reduction in ergonomic risk factors, can positively impact various job performance metrics, including productivity, service quality, and customer satisfaction. Additionally, talent retention poses a significant challenge for the tourism and hospitality industry, which experiences high turnover rates. However, ergonomics can serve as a means to address this issue by establishing a supportive work environment that emphasizes employee well-being and contentment. When employees perceive that their well-being, comfort, and safety are prioritized, they are more inclined to remain with the organization for an extended period. The incorporation of ergonomic interventions can help decrease work-related injuries, prevent burnout, and enhance job satisfaction, ultimately bolstering talent retention efforts.

Importantly, talent retention practices hold immense potential for providing a notable competitive edge within the tourism and hospitality industry. By prioritizing the retention of skilled and seasoned employees, organizations can uphold superior service quality, customer satisfaction, and overall operational excellence. This differentiation positions them favorably against competitors and contributes to long-term prosperity within the industry. Creating an engaging and fulfilling work environment is a central aspect of talent retention strategies. When employees are actively engaged and satisfied, they are more likely to demonstrate increased productivity, deliver exceptional customer service, and contribute positively to the organization’s culture and reputation. By understanding the factors that influence employee engagement and satisfaction, organizations can implement specific initiatives designed to improve these aspects, leading to enhanced talent retention.

In the tourism and hospitality industry, organizations have the opportunity to invest in training and development programs that aim to enhance the skills and competencies of their employees. By providing avenues for professional growth and advancement, organizations demonstrate a strong dedication to employee development, which in turn can foster increased employee loyalty and reduce turnover rates. Also, offering ongoing training initiatives enables employees to stay abreast of industry trends and further improve their job performance, ultimately benefiting the organization as a whole. Moreover, in the tourism and hospitality industry, organizations should prioritize work engagement as a favorable attribute when selecting and recruiting employees. By identifying individuals who exhibit high levels of engagement, organizations can enhance the likelihood of hiring motivated, dedicated, and enthusiastic individuals who genuinely enjoy their work. This approach contributes to cultivating a positive work environment and elevating the overall team performance.

Finally, the design of job roles holds a significant influence over employee engagement within the tourism and hospitality industry. Organizations should strive to create meaningful and challenging positions that allow employees to utilize their skills and abilities effectively. Implementing job enrichment techniques, such as granting increased autonomy, introducing task variety, and providing constructive feedback, can further enhance work engagement. These practices offer employees a sense of purpose, accomplishment, and personal growth, ultimately fostering a more engaged workforce.

7. Limitations and Future Research

Although examining the correlation between ergonomics, job performance, work engagement, and talent retention in the tourism and hospitality industry offers significant insights, there are limitations and avenues for future research that warrant consideration. Given the industry’s diverse nature, which encompasses sectors such as hotels, restaurants, travel agencies, and event management, future studies could delve into how the influence of ergonomics on job performance, work engagement, and talent retention may vary across these distinct sectors. Furthermore, incorporating cultural, organizational, and regional differences within the industry could provide a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the subject matter. By addressing these aspects, future research can contribute to a more robust body of knowledge in this field.

In the tourism and hospitality industry, organizations commonly have multiple hierarchical levels, encompassing front-line employees, supervisors, and managers. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics between ergonomics, job performance, work engagement, and talent retention, future research could employ a multi-level analysis approach. This approach would investigate how these factors interplay across different organizational levels, shedding light on the intricate complexities involved in these relationships. By adopting such an approach, researchers can uncover valuable insights that account for the specific dynamics at each level within the organization.

Additionally, it is important to consider that there might be other factors that play a role in mediating or moderating the relationship between ergonomics, job performance, work engagement, and talent retention. Factors such as the organizational culture, leadership style, job characteristics, and individual differences could potentially influence these relationships. Conducting further research to explore these factors would provide valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms and boundary conditions that shape the impact of ergonomics on job performance and employee outcomes. By understanding these additional factors, organizations can gain a more comprehensive understanding of how to optimize ergonomics and its effects on employee performance and well-being.

The tourism and hospitality industry is subject to continuous transformation, with technological advancements exerting a substantial influence on work environments and processes. To gain deeper insights, future research could investigate the repercussions of emerging technologies such as automation, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality on ergonomics, job performance, work engagement, and talent retention within the industry. By comprehending how these technologies intersect with ergonomic factors, organizations can refine the design of future work environments to optimize employee performance and well-being. This research would offer valuable guidance for effectively integrating technology while ensuring a positive impact on employees’ work experiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.E.-S., B.S.A.-R., M.H.A.e., S.L. and H.A.K.; data curation, B.S.A.-R., S.S. and H.A.K.; formal analysis, B.S.A.-R. and H.A.K.; funding acquisition, A.M.E.-S.; investigation, B.S.A.-R., S.S. and H.A.K.; methodology, B.S.A.-R., M.H.A.e. and H.A.K.; project administration, A.M.E.-S.; resources, B.S.A.-R., M.H.A.e., O.A., S.L. and H.A.K.; software, B.S.A.-R., S.S. and H.A.K.; supervision, B.S.A.-R.; validation, B.S.A.-R. and H.A.K.; visualization, B.S.A.-R. and H.A.K.; writing—original draft, A.M.E.-S., B.S.A.-R., M.H.A.e., O.A. and H.A.K.; writing—review and editing, B.S.A.-R., O.A., S.L. and H.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to King Saud University, Saudi Arabia, for funding this work through the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2023R133), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Ergonomics-Related Job Factors Coluci et al. (2009) [142] |

| Ergo.1. Performing the same task over and over. |

| Ergo.2. Working very fast for short periods (lifting, grasping, pulling, etc.). |

| Ergo.3. Having to handle or grasp small objects. |

| Ergo.4. Insufficient breaks or pauses during the workday. |

| Ergo.5. Working in awkward or cramped positions. |

| Ergo.6. Working in the same position for long periods (standing, bent over, sitting, kneeling, etc.). |

| Ergo.7. Bending or twisting your back awkwardly. |

| Ergo.8. Reaching or working over your head or away from your body. |

| Ergo.9. Hot, cold, humid, wet conditions. |

| Ergo.10. Carrying, lifting, or moving heavy materials or equipment. |

| Ergo.11. Continuing to work when injured or hurt. |

| Ergo.12. Work scheduling (overtime, length of workday). |

| Ergo.13. Using tools (design, weight, vibration, etc.). |

| Ergo.14. Working without any type of training. |

| Employee Job Performance Kundu et al. (2019) [143] |

| EJP.1. I make sure that my work meets/exceeds performance standards. |

| EJP.2. I meet/exceed my goals. |

| EJP.3. I complete my tasks on time. |

| EJP.4. I respond quickly when problems come up. |

| Work engagement Saks (2006) [144] |

| WE.1. I really “throw” myself into my work. |

| WE.2. Sometimes I am so into my work that I lose track of time. |

| WE.3. This work is all-consuming; I am totally into it. |

| WE.4. My mind often wanders and I think of other things when doing my work (R). |

| WE.5. I am highly engaged in this work. |

| Talent retention Mujtaba et al. (2022) [145] |

| TR.1. My hotel/travel agency provides career development opportunities to retain key employees. |

| TR.2. Managerial support of the hotel/travel agency inspires me to continue my job. |

| TR.3. The conducive environment of my hotel/travel agency motivates talented employees to stay a longer period. |

| TR.4. Attractive compensation and benefit incentives engage me to work with my hotel/travel agency. |

| TR.5. My hotel/travel agency provides more avenues to high performers for work–life balance |

| TR.6. My hotel/travel agency applies a performance-based rewards and recognition policy to motivate high performers to remain in the organization. |

| R: Reverse scoring |

Appendix B. Model Fit and Quality Indices

| Assessment | Criterion | Supported/Rejected | |

| Average path coefficient (APC) | 0.464, p < 0.001 | p < 0.05 | Supported |

| Average R-squared (ARS) | 0.567, p < 0.001 | p < 0.05 | Supported |

| Average adjusted R-squared (AARS) | 0.565, p < 0.001 | p < 0.05 | Supported |

| Average block VIF (AVIF) | 2.985 | acceptable if ≤5, ideally ≤3.3 | Supported |

| Average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF) | 2.292 | acceptable if ≤5, ideally ≤3.3 | Supported |

| Tenenhaus GoF (GoF) | 0.598 | small ≥0.1, medium ≥0.25, large ≥0.36 | Supported |

| Sympson’s paradox ratio (SPR) | 1.000 | acceptable if ≥0.7, ideally = 1 | Supported |

| R-squared contribution ratio (RSCR) | 1.000 | acceptable if ≥0.9, ideally = 1 | Supported |

| Statistical suppression ratio (SSR) | 1.000 | acceptable if ≥0.7 | Supported |

| Nonlinear bivariate causality direction ratio (NLBCDR) | 1.000 | acceptable if ≥0.7 | Supported |

References

- Al-Romeedy, B.S.; Mohamed, A.A. Does Strategic Renewal Affect the Organizational Reputation of Travel Agents through Organizational Identification? Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiman, A.; Kaivo-oja, J.; Parviainen, E.; Takala, E.-P.; Lauraeus, T. Human factors and ergonomics in manufacturing in the industry 4.0 context–A scoping review. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.M.; Stevens, N.; McLean, S.; Hulme, A.; Read, G.J. Human Factors and Ergonomics and the management of existential threats: A work domain analysis of a COVID-19 return from lockdown restrictions system. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2021, 31, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, M.M. Improving ergonomic conditions at hospitality industry. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckel, J.L.; Fisher, G.G. Telework and worker health and well-being: A review and recommendations for research and practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraboni, F.; Brendel, H.; Pietrantoni, L. Evaluating Organizational Guidelines for Enhancing Psychological Well-Being, Safety, and Performance in Technology Integration. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroemer, A.D.; Kroemer, K.H. Office Ergonomics: Ease and Efficiency at Work; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, T.A.; Ayoko, O.B.; Ashkanasy, N.M. A Socio-Technical Perspective on the Application of Green Ergonomics to Open-Plan Offices: A Review of the Literature and Recommendations for Future Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroz, S.; Haque, M.I. Ergonomics in the workplace for a better quality of work life. In Ergonomics for Improved Productivity: Proceedings of HWWE 2017; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 503–511. [Google Scholar]

- Dandale, C.; Telang, P.A.; Kasatwar, P. The Effectiveness of Ergonomic Training and Therapeutic Exercise in Chronic Neck Pain in Accountants in the Healthcare System: A Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e35762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, P.; Khan, M. Musculoskeletal disorders among the Bone Carving Artisans of Uttar Pradesh: A study on Cognitive space and accessory design for MSD and health-related problems. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 64, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenso, B.; Mbachu, C.; Etiaba, E.; Huss, R.; Manzano, A.; Onwujekwe, O.; Uzochukwu, B.; Ezumah, N.; Ensor, T.; Hicks, J.P. Which mechanisms explain the motivation of primary health workers? Insights from the realist evaluation of a maternal and child health programme in Nigeria. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Döngül, E.S.; Uygun, S.V.; Öztürk, M.B.; Huy, D.T.N.; Tuan, P.V. Exploring the relationship between abusive management, self-efficacy and organizational performance in the context of human–machine interaction technology and artificial intelligence with the effect of ergonomics. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalakoski, V.; Selinheimo, S.; Valtonen, T.; Turunen, J.; Käpykangas, S.; Ylisassi, H.; Toivio, P.; Järnefelt, H.; Hannonen, H.; Paajanen, T. Effects of a cognitive ergonomics workplace intervention (CogErg) on cognitive strain and well-being: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. A study protocol. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, A.; Ghafoorpoor Yazdi, P.; Hashemipour, M. Interactive design of storage unit utilizing virtual reality and ergonomic framework for production optimization in manufacturing industry. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. (IJIDeM) 2019, 13, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Arora, A. A Study on Effect of Job Design and Ergonomics on Employee Performance in Indian Automotive Sector. Metamorphosis 2021, 20, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohunakin, F.; Adeniji, A.A.; Ogunlusi, G.; Igbadumhe, F.; Sodeinde, A.G. Talent retention strategies and employees’ behavioural outcomes: Empirical evidence from hospitality industry. Bus. Theory Pract. 2020, 21, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqshbandi, M.M.; Kabir, I.; Ishak, N.A.; Islam, M.Z. The future of work: Work engagement and job performance in the hybrid workplace. Learn. Organ. 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine, A.K.; Rudolph, C.W.; Zacher, H. Thriving at work: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 973–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, F.H. Attracting and retaining skilled and professional staff in remote locations of Australia. Rangel. J. 2011, 33, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzewi, H.N.; Augustine, A.; Mohammed, I.; Godson, O. Physical work environment and employee performance in selected brewing firms in Anambra State, Nigeria. J. Good Gov. Sustain. Dev. Afr. 2018, 4, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, N.; Sharma, S.K.; Ganguly, C. Compensation and Reward Management within Domestic & International Airlines. KEPES 2023, 21, 190–202. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Al Mamun, A.; Hoque, M.E.; Hussain, W.M.H.W.; Yang, Q. Work design, employee well-being, and retention intention: A case study of China’s young workforce. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christy, D.V. Ergonomics and Employee Engagement. Int. J. Mech. Eng. 2019, 10, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeister, K.; Gibbons, A.; Schwatka, N.; Rosecrance, J. Ergonomics Climate Assessment: A measure of operational performance and employee well-being. Appl. Ergon. 2015, 50, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pheasant, S.; Haslegrave, C.M. Bodyspace: Anthropometry, Ergonomics and the Design of Work; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Houssin, R.; Renaud, J.; Gardoni, M. A review of methodologies for integrating human factors and ergonomics in engineering design. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 4961–4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatcher, A.; Zink, K.J.; Fischer, K. Human Factors for Sustainability: Theoretical Perspectives and Global Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri, L.; Palomba, I.; Merati, F.A.; Rauch, E.; Vidoni, R. Design of human-centered collaborative assembly workstations for the improvement of operators’ physical ergonomics and production efficiency: A case study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistan, T.; Gardi, A.; Sabatini, R. Machine learning and cognitive ergonomics in air traffic management: Recent developments and considerations for certification. Aerospace 2018, 5, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, S.O.; Kilskar, S.S.; Fossum, K.R. Missing focus on Human Factors–organizational and cognitive ergonomics–in the safety management for the petroleum industry. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part O J. Risk Reliab. 2017, 231, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednárová-Gibová, K. Organizational ergonomics of translation as a powerful predictor of translators’ happiness at work? Perspectives 2021, 29, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesener, T.; Gusy, B.; Wolter, C. The job demands-resources model: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Work Stress 2019, 33, 76–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radic, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H.; Law, R. Job demands–job resources (JD-R) model, work engagement, and well-being of cruise ship employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tuckey, M.R.; Bakker, A.; Chen, P.Y.; Dollard, M.F. Linking objective and subjective job demands and resources in the JD-R model: A multilevel design. Work Stress 2023, 37, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollter Bergman, M.; Berlin, C.; Babapour Chafi, M.; Falck, A.-C.; Örtengren, R. Cognitive Ergonomics of Assembly Work from a Job Demands–Resources Perspective: Three Qualitative Case Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borst, R.T.; Kruyen, P.M.; Lako, C.J. Exploring the job demands–resources model of work engagement in government: Bringing in a psychological perspective. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2019, 39, 372–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleem, M. The influence of talent management on performance of employee in public sector institutions of the UAE. Public Adm. Res. 2019, 8, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, L.E. A critical reflection on the psychology of retention-Psychology of Retention: Theory, Research and Practice, by Melinde Coetzee, Ingrid L. Potgieter and Nadia Ferreira (Eds.). SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2019, 45, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, K.; Park, J. The life cycle of employee engagement theory in HRD research. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2019, 21, 352–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peifer, C.; Engeser, S. Advances in Flow Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Khairy, H.A.; Lee, Y.M. ENHANCING CUSTOMERS’BRAND COMMITMENT: A MULTIDIMENSIONAL PERSPECTIVE OF BRAND CITIZENSHIP BEHAVIOR IN EGYPTIAN HOTELS. Int. J. Recent Trends Bus. Tour. (IJRTBT) 2018, 2, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Attallah, N.F. Evaluation of perceived service quality provided by tourism establishments in Egypt. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 15, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherehiy, B.; Karwowski, W. The relationship between work organization and workforce agility in small manufacturing enterprises. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2014, 44, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Maspero, M.; Golightly, D.; Sheffield, D.; Staples, V.; Lumber, R. Nature: A new paradigm for well-being and ergonomics. In New Paradigms in Ergonomics; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 142–155. [Google Scholar]

- Faez, E.; Zakerian, S.A.; Azam, K.; Hancock, K.; Rosecrance, J. An assessment of ergonomics climate and its association with self-reported pain, organizational performance and employee well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirios, P.; Fabio, F.; Francesco, M. A Methodological Framework to Assess Mental Fatigue in Assembly Lines with a Collaborative Robot. In International Conference on Flexible Automation and Intelligent Manufacturing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 297–306. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi, R.; Smith, A. Overcoming COVID-19 pandemic: Emerging challenges of human factors and the role of cognitive ergonomics. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 2023, 24, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishola, B. Handling waste in manufacturing: Encouraging re-manufacturing, recycling and re-using in United States of America. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 39, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; Wu, Z.; Bai, R.; Meng, G. Ergonomic and efficiency analysis of conventional apple harvest process. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2019, 12, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintada, A.; V, U. Improvement of productivity by implementing occupational ergonomics. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2022, 39, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.R.; Hurtado, A.L.B.; Batiz, E.C. Ergonomics management with a proactive focus. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 4509–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selamat, M.N.; Mukapit, M. The relationship between task factors and occupational safety and health (OSH) performance in the printing industry. Akademika 2018, 88, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M.M.; Huang, Y.-H.; O’Neill, M.J.; Schleifer, L.M. Flexible workspace design and ergonomics training: Impacts on the psychosocial work environment, musculoskeletal health, and work effectiveness among knowledge workers. Appl. Ergon. 2008, 39, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, M.R. Paradigm shift in employee engagement–A critical analysis on the drivers of employee engagement. Int. J. Inf. Bus. Manag. 2018, 10, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Lucas, G.; Roll, S.C. Impacts of working from home during COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental well-being of office workstation users. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, M.K.; Dahalan, N.A.; Mohammed, I.H.; Shah, M.M.; Azman, N.N.M. Supervisor Feedback, Ergonomics and Job Performance: A Study at One of Malaysia’s Frontline Government Agency. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2016, 6, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Eldor, L.; Vigoda-Gadot, E. The nature of employee engagement: Rethinking the employee–organization relationship. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 526–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanana, N.; Sangeeta. Employee engagement practices during COVID-19 lockdown. J. Public Aff. 2021, 21, e2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallemand, C. Contributions of participatory ergonomics to the improvement of safety culture in an industrial context. Work 2012, 41, 3284–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, B.A.; Broberg, O. Human well-being and system performance in the transition to industry 4.0. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2020, 76, 102936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, C.A.; Araci, O.; Karacay, G.; Calisir, F. The mediating effect of rewarding on the relationship between employee involvement and job satisfaction. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2017, 27, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voordt, T.v.d.; Jensen, P.A. The impact of healthy workplaces on employee satisfaction, productivity and costs. J. Corp. Real Estate 2023, 25, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, M.M.; Tarar, A.H. Work Autonomy, Organizational Climate and Employee Engagement. Pak. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 18, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Vischer, J.C. The concept of workplace performance and its value to managers. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2007, 49, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, K. Workplace environment and its impact on organisational performance in public sector organisations. Int. J. Enterp. Comput. Bus. Syst. 2011, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Adum, A.N.; Ebeze, U.V.; Ekwugha, U.P.; Okika, C.C. Opinion Poll on Nigerian University Students Awareness of the health Implications of Inadequate Ergonomic furniture in Universities of South-East Nigeria. Commun. Panor. Afr. Glob. Perspect. 2016, 2, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Alrashed, W.A. Ergonomics and work-related musculoskeletal disorders in ophthalmic practice. Imam J. Appl. Sci. 2016, 1, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.S.L.; Raj, S.S. Role of leaders for boosting morale of employees in IT sector with special reference to Technopark, Trivandrum. Int. J. Manag. Res. Rev. 2016, 6, 1155. [Google Scholar]

- Straus, E.; Uhlig, L.; Kühnel, J.; Korunka, C. Remote workers’ well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement: Which resources should HRM improve during COVID-19? A longitudinal diary study. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 2960–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.A.; Mahmood, M.; Fan, L. Why individual employee engagement matters for team performance? Mediating effects of employee commitment and organizational citizenship behaviour. Team Perform. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 25, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]