Abstract

The MICE (meetings, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions) industry consists of various stakeholders and their collaboration is essential in achieving the success of the entities involved. Yet, limited attention has been paid in the literature to examining cooperation among them. Thus, this research intends to understand the impact of social capital on supply chain integration in the MICE industry and the influence of supply chain integration on corporate performance and MICE destination competitiveness. Based on purposive sampling to recruit respondents working in the MICE industry in Busan, Korea, surveys were distributed online and offline. A total of 158 valid samples were utilized for data analysis, in which partial least squares (PLS)-SEM was conducted. According to the results of this study, relational and cognitive social capital affects supply chain integration and enhanced supply chain integration leads to higher corporate performance and destination competitiveness. The findings unearth novel understanding regarding the importance and function of collaboration among stakeholders in the MICE industry, from the perspective of social capital and supply chain integration, that offers valuable theoretical and practical implications.

1. Introduction

The MICE (meetings, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions) industry, which is highly valued due to its capability to boost local economies and to facilitate socio-cultural development, is expected to continue its development and to expand its market size. According to the market analysis report by Grand View Research [1], continuous growth of the global MICE market is forecasted, in which it is predicted that the market size is expected to reach USD 1563.29 billion by 2030, from USD 986.42 billion in 2022. As the success of a host city as a MICE destination leads to positive ripple effects that extend to various areas that are beneficial to the country, governments invest large sums of spending and effort to foster the growth of this industry. In fact, the existing literature has identified local government support as one of the important factors that affect the attractiveness of a destination in the MICE industry market [2]. While government support is critical in accelerating the development of the MICE industry, one of the most critical yet neglected antecedents to the growth of the MICE industry is that attention needs to be paid to including the role of MICE industry stakeholders and their partnership.

As a case in point, the success of the global MICE destination Madrid, which was listed as the world’s top meetings and conferences destination in the World Travel Awards in 2022, is credited to the efforts of the Madrid Convention Bureau to bring together both public and private companies and organizations of Madrid’s MICE industry [3]. That is, strong partnerships formed among the entities in this industry contributed to the accomplishment of Madrid being recognized as a global MICE destination. Stakeholders in the MICE industry include convention and visitors bureaus (CVB), professional conference organizers (PCO), professional exhibition organizers (PEO), venues, incentive houses, accommodation, tourism organizations, and any others that are involved in organizing an event in the MICE industry [4]. To hold an event, these stakeholders need to closely collaborate and, thus, cooperation among them is essential [5]. By applying the proposition of stakeholder theory, as suggested by Freeman [6], that stakeholders are those that are affected by and affect the achievement of an organization, Lau, Milne, and Chi Fai Chui [7] defined stakeholders in the event industry context as being “people and organizations with a legitimate interest in an event’s outcomes.” As such, the function of stakeholders is critical in determining event performance.

Although limited, some studies have explored the role of specific type of a stakeholder in enhancing the attractiveness and survival of holding an event [2]. Specifically, local government is known to play an important role in maximizing attractiveness of a destination to host event and in enhancing MICE industry performance [2]. However, the focus of the current literature on government as the solely important key player offers a fragmented understanding of what determines the successful performance of the MICE industry. In addition, as prior studies have mostly delved into stakeholder performance or their perceptions on an individual level, regarding issues including decision making, performance, MICE destination competitiveness, and sustainable practices [4,8], the function of partnership among MICE industry stakeholders is tangentially explored in the existing literature. According to the proposition of stakeholder theory, the performance of stakeholders is maximized when they collaborate, as the resources shared among them empower them with greater competitiveness [9]. Considering the importance of communal work among stakeholders, this is an important yet rarely examined issue in the MICE industry literature.

To address such a research gap, this research intends to understand the antecedents to and outcomes of supply chain integration in the MICE industry. The concepts of social capital and supply chain integration, which are yet to be widely explored in the MICE tourism literature, will be applied in this research. Supply chain integration, which indicates strategic collaboration among stakeholders to effectively and efficiently manage one’s supply chain [10], is utilized to explore the strength of the partnership among MICE industry stakeholders in this research. Among different types of supply chain integration, the notion of external supply chain integration, which involves cooperative work process among a firm and its external stakeholders, will be utilized in this study. Social capital, which refers to cognitive, relational, and structural resources based on partnership that promotes the development of organizations [11], is examined as the precursor of such a collaboration. Specifically, the application of the notions of social capital and supply chain integration in this research is a pioneering attempt as barely any studies have investigated the function of suppliers, rather than general stakeholders, in the MICE industry.

The structure of this paper will unfold as follows. First, in the literature review section, discussion on existing knowledge and analysis of the MICE industry, stakeholders in the MICE industry, social capital, and supply chain integration is outlined. In the hypothesis development section, a series of hypotheses are delineated based on research objectives, which are backed up by findings from previous studies. The research method section includes discussion on research instruments, data collection, and data analysis. In the results section that follows, results from data analysis are presented. Last, the paper concludes with the conclusion and discussion section, which summarizes the findings of this research and suggests theoretical and practical implications.

2. Literature Review

2.1. MICE Industry

The MICE industry, which consists of meetings, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions, represents events such as those in the following descriptions [12]. Meetings refers to events that are attended by a relatively small number of people compared to other events, and includes corporate meetings, workshops, and seminars. Incentives refers to incentive tourism, in which holiday travel is organized to reward and motivate the employees of a company or loyal customers. Conferences are large meetings that tend to include educational sessions, participant discussions, and social gatherings. Exhibitions refers to events in which products and services are presented to audiences to induce a sale or to inform visitors about specific content. As all four dimensions of the MICE industry embrace business-related purposes, some papers label them as business events [13].

The importance of the MICE industry has been recognized in terms of its economic and socio-cultural impact [12,14]. The host industry could enjoy a multiplier effect on its local economies, including accommodation, transportation, attractions, restaurants, and such economic impact is especially important considering the findings of existing studies that average MICE tourists tend to spend more than average leisure tourists [15]. Moreover, development of the MICE industry could create jobs, complement the attractiveness of the destination as a place to travel to, promote cultural exchange among countries from different cultures in which new ideas are shared, and enhance sustainable regional development [16,17].

In accordance with the importance of the MICE industry, prior studies have explored factors that make destinations attractive to hold an event, and the factors identified are mostly site attributes such as exhibition center facilities, accessibility, and the image of the convention and exhibition center [18]. Likewise, factors that contribute to MICE destination competitiveness encompass those that relate to the infrastructure of the destination including facilities, hotel room availability, attractions, environment, safety, and security [19]. An, Kim, and Hur [20] identified that the venue attributes that are perceived to be important differ among different types of organizations in the MICE industry, such that the importance of factors such as “number, size, and quality of meeting room”, “attractions and entertainment opportunity”, and “shopping opportunities and accessibility to shopping area” varied across different entities.

From the perspective of the event attendee, elements that motivate them to travel for the purpose of attending events include venue, accommodation, transportation, other support services, sustainability, the destination leisure environment, the destination economic environment, and cluster effects [21,22,23]. Similarly, decoration of the hall and artifacts were found to affect attendee satisfaction [24]. Additional factors that were found to impact attendee motivation and satisfaction include education, networking, and the destination’s image [25,26]. As such, factors that have been explored to affect MICE destination performance, attendee motivation, and satisfaction are mostly confined to the physical aspects of the destination infrastructure. In turn, this offers a limited view regarding what efforts should be made to attract events and maximize the satisfaction of the attendees and stakeholders involved in the event.

2.2. Stakeholders in the MICE Industry

One of the factors that is important for maximizing MICE event outcomes encompasses the function of MICE industry stakeholders. The constituents of stakeholders discussed in the MICE industry varied by research. Some research segmentalized the categorization of stakeholders, such as the work of van Niekerk and Getz [27], which identified the festival organization, coproducers, facilitators, allies and collaborators, regulators, suppliers and venues, and the audience and those impacted as the stakeholders involved in festivals, while others identified stakeholders more broadly, such as Clarkson [28], who classified stakeholders as primary and secondary stakeholders. The existing literature regarding stakeholders in the event industry examined the role of individual stakeholders, in terms of their function in the survival and attractiveness of an event [27,29]. Moreover, past studies have argued that each stakeholder has different expectations and interests that they seek from an event, such that venders seek profit making [30], sponsors expect to receive a return on their investment [31], and local government is interested in promoting the socioeconomic development of the destination [27]. In addition, Adongo, Kim and Elliot [32] examined perceptions stakeholders have of other stakeholders regarding trust, control, dependence, and altruism.

As such, prior studies that dealt with event stakeholders paid attention to each of the stakeholders, respectively rather than examining the interrelationship between or collaboration among the stakeholders [33,34]. In fact, the importance of a collaborative stakeholder strategy in an event industry has been acknowledged in the current literature [29]. Relationships among stakeholders become important in situations including those where resources are limited, conflicts and problems exist among stakeholders, and when information is asymmetric [35]. Thus, collaborative relationships among stakeholders are important as such collaboration enables them to share information and various types of benefits, exchange resources, enhances stakeholder satisfaction and trust, and facilitates decision making in the sense that collaboration improves its quality [30,36,37].

According to resource dependency theory, stakeholders need to be interdependent in sharing resources for them to survive and the resources shared are important in determining organizational competitiveness [38]. Resources include tangible attributes including monetary resources, as well as intangible elements including skills, knowledge reputation, trustworthiness [39] and these resources lend stakeholders power to exert influence in determining organizational outcomes. Moreover, according to the notion of network centrality, as the number and closeness among one another within a stakeholder network is high, this lends them power [40], and such collaboration allows them to achieve individual as well as communal benefits for the entities involved [41]. In the context of an event, the network structure and relationships among stakeholders has also been identified to be influential in leading an event to success, but past studies have induced such conclusions from interviews and case studies rather than empirically verifying this proposition, and attention has only been paid to identifying who the stakeholders are and what the network structure is like [42,43]. Despite the importance and potential of collaborative relationships among stakeholders in the MICE industry to positively impact MICE industry performance, limited research has been conducted regarding the power of stakeholders in the existing literature.

While a smattering of research has been conducted regarding the function of MICE industry stakeholders, local government has been explored in the current literature as an entity that impacts MICE industry performance [2,44]. However, the conclusions of the existing studies regarding the role of local government are fragmented. Studies such as Kim et al. [2] suggest that for MICE events to survive, local government support is one of the most important factors, indicating that relationships among MICE industry players, including MICE event organizers and local authorities, are important. On the other hand, others have found that the survival of events is not related to government support, such as the work of He et al. [45], which concluded that exhibition survival is not related to government support.

The work of Lee, Lee, and Jones [46] is one of the few studies that examined the relationships among different MICE industry stakeholders and CVBs (convention and visitor bureaus) on CVB performance. Specifically, they found that goal conflict and interdependence among MICE industry stakeholders and CVBs impacted collaborative relationships. However, the findings suggest that in the case of MICE stakeholders in Korea, information asymmetry among the stakeholders and CVBs does not impact collaborative relationships and the authors explain that MICE industry stakeholders in Korea tend to believe that CVBs actively collaborate with them regardless of information asymmetry. While the findings of this research suggest the importance of collaborative relationships among MICE industry stakeholders and CVBs, the study did not address relationships among the stakeholders. Accordingly, the communal power of MICE industry stakeholders in achieving MICE industry performance success warrants investigation and such an issue needs to be explored with a theoretical framework. Therefore, this research applies the notion of social capital and supply chain integration to understand the role of social capital among MICE industry stakeholders and the integration of their functions in maximizing their performance.

As such, the role of MICE industry stakeholders has yet to be examined in a microscopic perspective and inconsistency in findings regarding the function of local government calls for further research to validate their role. Therefore, there is a need to expand our knowledge regarding the impact of the relationship among different stakeholders in the success of MICE industry performance.

2.3. Social Capital

Social capital refers to resources that are accumulated among individuals and organizations within a supply chain network based on their trust and partnership and structural configuration [47]. Originally, the relational aspect of the social capital was emphasized in the literature, in which social capital was viewed as a relational resource that contributes to the growth of individuals and organizations that engage in networking with one another [48]. Later works expanded the range of resources that are included in the notion of social capital, including “economic, political, technological, and cultural resources” [49]. As such, prior works have identified a range of elements that constitute social capital. Among such variations, the most recognized set of dimensions of social capital includes a structural dimension (networking and mutual relationships among members of an organization), a relational dimension (shared norms and trust constructed via social interactions among members of an organization), and a cognitive dimension (shared understanding among members of an organization) [50].

While many of the existing studies argue that all three dimensions of cognitive, relational, and structural dimensions enhance firm performance [51,52,53], some studies have argued that one specific dimension is more effective than the other. For instance, Autry and Griffis [47] found that relational and structural dimensions enhance operational and innovation-oriented firm performance, while Muniady et al. [54] identified that structural capital impacts firm performance in the case of a micro-enterprise. Such divergent findings in the existing literature suggests the need for further validation regarding whether social capital itself results in higher firm performance or whether a specific dimension of the social capital exerts influence in enhancing positive outcomes for an organization.

Social capital has been recognized as helping individuals and organizations within a network to acquire meaningful information that could eventually help them to produce valuable outcomes [55,56,57]. As the social capital a firm has is strengthened, operational performance and overall firm performance has been identified as being enhanced as the information exchange among stakeholders is facilitated [58]. In a similar vein, social capital has been recognized to have power in encouraging knowledge sharing among members of a group, which in turn boosts the knowledge-based capability within an organization [51]. Moreover, collaboration among the entities involved in the supply chain empowers them with flexibility, which leads to higher firm performance [58]. The importance of enhanced social capital in an organization has also been identified in terms of enhanced organizational creativity and organizational efficiency [57]. Although the value of communal resources shared among stakeholders has been recognized in the existing literature, very limited attempts have been made in exploring its role within the MICE industry by applying the notion of social capital.

2.4. Supply Chain Integration

Supply chain integration refers to the degree to which stakeholders (i.e., company, suppliers, customers) within one’s supply chain collaborate with one another [59]. While early research on supply chain integration argued that this is a unidimensional concept (e.g., [60,61]), the view that supply chain integration is a multi-dimensional concept is more dominant [62]. While some have outlined a two-dimensional approach including internal and external integration, where external integration encompasses supplier and customer integration [63], others have dissected external integration and outlined three types of supply chain integration: customer integration, internal integration, and external integration [64].

Customer integration concerns a cooperative process through which firms attempt to enhance their understanding of their customers’ needs and culture [65]. Identifying the needs of the customers and engaging customers in the decision-making processes enables companies to offer products and services that create the highest value for customers and to maximize customer satisfaction [10]. Internal integration involves structuralizing operational procedures of internal entities in collaborative processes. Through internal integration, the activities of different divisions within a firm are incorporated to work collectively instead of each division working independently [66]. External integration refers to a collaborative work process among a firm and its suppliers, through which entities engaged in this partnership aim to jointly eliminate unnecessary procedures involved while enhancing the efficiency of their work [64]. Based on external integration, firms engage in processes to establish a system through which they can exchange information with their suppliers [67]. The external integration procedure allows the firm and its suppliers to strategically collaborate in terms of activities including establishment of communal plans and practices as well as the development of conjoint products [68]. In the current study, external supply chain integration was examined as this research intends to examine cooperation among firms and related stakeholders on an external level.

The collaboration formed among entities involved in supply chain integration includes communal management among stakeholders to expedite and maximize the efficiency of their internal and external operational processes [69]. Through supply chain integration, the efficiency of the supply chain structure can be enhanced and a company’s competitiveness can be enhanced via effectively executing the decision-making process required within a company. Moreover, companies involved in supply chain integration are able to achieve seamless operation as flexibility and agility are enhanced, which in turn leads to improved operational performance [70,71]. Supply chain integration also enables individuals involved in the supply chain to make decision-making effective, which ultimately plays an important role in offering high value to customers [72]. While collaboration among entities involved in the MICE industry supply chain is also important in facilitating the processes involved and in enhancing the outcomes related to holding MICE events, as discussed above, very limited attention has been paid to examining the relationships among MICE industry stakeholders in terms of supply chain integration and its impact. In fact, barely any research has applied a theoretical framework such as the notion of supply chain integration in examining collaborative relationships among stakeholders in the MICE industry.

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Social Capital and Supply Chain Integration

In the current literature, enhanced social capital has been identified to influence development of supply chain integration [73,74]. For entities to strengthen integration of supply chain, relational resources developed based on trust are essential as such resources facilitate the relationship building process [75]. As the nature of social capital entails trust, shared vision and commitment and, thus, social capital can influence supply chain integration [47]. While some studies have identified that a specific type of capital has positive impact on supply chain integration [76,77], the consensus is that all three dimensions of social capital enhance supply chain integration. For instance, in the context of food processing industry, Saleh [78] found that social capital has a positive influence on supply chain integration. Similarly, social capital has been identified as the antecedent to sustainable supply chain management [79]. Based on this background, this research proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypotheses 1a (H1a).

Structural capital has a significant impact on supply chain integration in the MICE industry.

Hypotheses 1b (H1b).

Relational capital has a significant impact on supply chain integration in the MICE industry.

Hypotheses 1c (H1c).

Cognitive capital has a significant impact on supply chain integration in the MICE industry.

3.2. Supply Chain Integration and Corporate Performance

Intensification of supply chain integration has been found to lead to higher firm performance in existing studies [80,81]. Firms are able to improve operational performance in terms of various aspects including enhanced product quality, cost efficiency, and flexibility [82]. When integration of a supply chain is intensified, information is actively shared among stakeholders in the supply chain, which allows transparency among them [83]. This information exchange allows the entities involved to understand the operational activities of others, which in turn results in enhanced transparency among them. Moreover, when supply chain integration is intensified, firms are able to achieve higher performance as firms can boost creativity and innovation [84]. As such, the numerous beneficial outcomes of supply chain integration enable firms to improve their own performance. The importance of supply chain integration in augmenting firm performance in the MICE industry can also be inferred from the work of Rittichainuwat et al. [85], which concluded that the collective effort of suppliers in executing operational and marketing activities during the COVID-19 pandemic expedited the recovery of the MICE industry in Thailand. Against this backdrop, the current research presents the following hypothesis:

Hypotheses 2 (H2).

Supply chain integration has a significant impact on corporate performance in the MICE industry.

3.3. Supply Chain Integration and MICE Destination Competitiveness

Destination competitiveness is a concept that has been widely studied in the existing literature [86,87,88]. One of the most widely cited definitions of destination competitiveness was coined by Crouch and Ritchie [89], stating that it is “the ability to increase tourism expenditure, to increasingly attract visitors while providing them with satisfying, memorable experiences and to do so in a profitable way, while enhancing the well-being of destination residents and preserving the natural capital of the destination for future generations” (p. 137). Accordingly, MICE destination competitiveness in this research is defined as the capability of the destination to attract more MICE event visitors and ultimately to enhance their satisfaction level. The work of Cronjé and du Plessis [87], which reviewed studies that dealt with destination competitiveness, concluded that the most frequently identified determinant of destination competitiveness in the literature is infrastructure, followed by events that take place in the destination from the supply side. Cronjé and du Plessis [87] outlined that activity factors and quality of service factors were most the frequently examined antecedent to destination competitiveness from the demand side. For infrastructure to be well developed, to offer satisfactory activities, and to provide high-quality services to visitors, collaborative work among stakeholders is essential. In fact, Kvasnová, Gajdošík, and Maráková [90] identified that the degree of partnership among tourism stakeholders has a positive influence on destination competitiveness. Moreover, enhanced supply chain integration has been known to improve product quality and the level of customer service [91]. Thus, supply chain integration among MICE industry stakeholders could play an important role in enhancing MICE destination competitiveness. In addition, the findings of the studies which identified that government support influences destination competitiveness [92,93] suggest that the role of suppliers can be an important determinant of destination competitiveness. Thus, the following hypothesis is suggested in this research:

Hypotheses 3 (H3).

Supply chain integration has a significant impact on MICE destination competitiveness in the MICE industry.

3.4. Corporate Performance and MICE Destination Competitiveness

According to one of the most widely utilized models of destination competitiveness, as suggested by Ritchie and Crouch’s work [94], destination management, such as the organizational aspects of tourism firms in the destination, serves as a trigger in boosting destination competitiveness. That is, the management and performance of firms within the tourism industry plays an important role in maximizing destination attractiveness. Moreover, the performance of stakeholders in the tourism industry, such as accommodation, airlines, and restaurants, could influence the overall experience and satisfaction level of tourists [95,96]. In the case of the MICE industry, increased corporate performance of the entities involved means that the quality and efficiency of the event organized is enhanced. Thus, this could lead to increasing MICE destination competitiveness. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypotheses 4 (H4).

Corporate performance has a significant impact on MICE destination competitiveness.

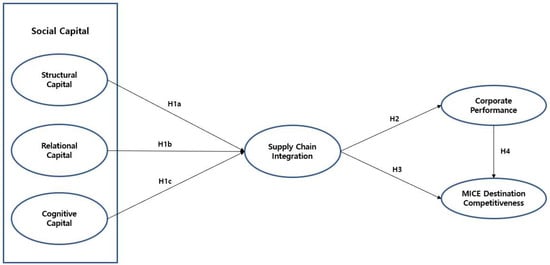

Based on the hypotheses suggested above, the following research model is proposed in this study, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed Research Model.

4. Research Method

4.1. Research Instrument

We constructed reflective multi-item measurements based on items adopted from previous studies. Measurements for social capital were adopted from Nahapiet and Ghosal [49] and Johnson, Elliott, and Drake [97]. A total 12 items to measure three dimensions of social capital (structural capital, relational capital, cognitive capital) were adopted (4 items for each dimension). Supply chain integration was operationalized using 6 items adopted from Narasimhan and Jayaram [98] and Huo et al. [59]. Lastly, corporate performance was operationalized using 4 items adopted from Younis, Sundarakani, and Vel [99] and Chen et al. [81] while destination competitiveness was operationalized using 3 items adopted from Lee, Choi, and Breiter [100] and Altinay and Kozak [86]. All items were measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The measurement items were validated and finalized based on consultation with experts currently working in the MICE industry.

4.2. Data Collection

Data was collected from October to December, 2021. Data collection was conducted based on purposive sampling to recruit respondents that work in the MICE industry (i.e., venue, PCO, PEO, event/promotion company, travel agency, other event related service providers) in Busan, Korea. Surveys were distributed online and offline. A total of 197 surveys were collected and 158 valid samples were utilized for final analysis.

The demographic characteristics of the respondents are as follows (see Table 1). In the case of gender, 52% (82 people) were male and 48% (76 people) were female, out of a total of 158 samples. As for the age distribution of respondents, those in their 20s accounted for the largest portion with 32% (51 people), followed by 30% (47 people) in their 40s, 27% (42 people) in their 30s, and 11% (18 people) in their 50s or older. Respondents’ current working organization consisted of 41% (65 people) working for venues such as convention centers and hotels, 34% (54 people) working for PCOs, 11% (18 people) for event related service providers, 5% (8 people) for PEOs, 3% (4 people) for events and promotions companies, travel agencies 1% (2 people), and others 5% (7 people). As for the length of service at the current job, more than 10 years accounted for the largest share at 33% (53 people), followed by less than 1 year at 25% (39 people), less than 3 years, less than 10 years at 16% (25 people), and less than 5 years were at 10% (16 people). Finally, as for the total length of service in the MICE industry, more than 10 years accounted for 42% (66 persons), followed by less than 1 year at 17% (27 persons), less than 3 years at 16% (25 persons), less than 10 years at 15% (23 people), and 10% (16 people) for less than 5 years.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Profiles of the Respondents.

4.3. Data Analysis

Before examining the model, common method bias should be checked in cross-sectional studies, particularly when both the dependent and independent variables are obtained from the same respondents. To examine this issue, a full-collinearity test was conducted through the variance inflation factor (VIF). As shown in Table 2, all VIF values were less than the threshold of 3.3, varying between 1 and 3.104, suggesting that common method bias was not a major issue in this model [101].

Table 2.

Results of Full-Collinearity test.

For data analysis, partial least squares (PLS)-SEM with Smart PLS 4.0 software was used. PLS-SEM is gaining popularity and has been widely utilized in the marketing and management literature in the last decade [102,103,104].

In this study, PLS-SEM was used for two reasons. Firstly, PLS-SEM is considered to be a useful method for analyzing small and medium sample sizes. It performs more efficiently in terms of statistical power and convergence when the size of the sample is small compared to other methods [102,105]. Therefore, considering the characteristics of this study, where the subject of the study was limited to stakeholders in the regional MICE industry, using PLS-SEM was deemed appropriate. Secondly, PLS-SEM is considered to be superior to the CB-SEM method when there is little prior knowledge of the structural relationships of variables or when the nature of the research is exploratory rather than confirmatory [102]. Therefore, PLS-SEM seems appropriate for this study because of its exploratory nature with limited prior research; as our research is one of the initial attempts to investigate the structural relationships of social capital and supply chain integration in the context of the MICE industry.

In accordance with recommendations by Hair et al. [102], we adopted a two-stage analytical procedure for PLS-SEM, first testing the measurement model (reliability and validity of the structures) and then examining the structural model.

5. Results

5.1. Measurement Model

PLS-SEM was applied to check the reliability and validity of the scale. First, the reliability of the construct was assessed through Cronbach’s Alphas and composite reliability (CR). Both the Cronbach’s Alphas and CR of all factors were greater than the 0.7 threshold (between 0.870 and 0.937) indicating that the reliability of the scale is satisfactory.

The convergent validity of the scale was assessed through average variance extracted (AVE) and factor loadings. AVE values were greater than the 0.5 threshold, varying between 0.667 and 0.842, and all the items have a loading above the threshold of 0.7 (see Table 3). Consequently, the convergent validity of the model was confirmed [102].

Table 3.

Validity and Reliability of the Scale.

The discriminant validity was assessed via the Fornell–Larcker criterion [105]. The square root of the AVE of each factor was greater than its corresponding correlation coefficients, suggesting the discriminant validity of the model (see Table 4). However, some recent criticism of the Fornell and Lacker [105] criteria suggests that they do not reliably detect the lack of discriminant validity in common research situations [106]. Thus, discriminant validity was tested again using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlation (HTMT) (see Table 5). Results show that all HTMT values were lower than the marginal threshold of 0.9, confirming an acceptable level of the discriminant validity of the model [106,107].

Table 4.

Fornell–Lacker Criterion.

Table 5.

HTMT (heterorait–monotrait) Analysis.

5.2. Structural Model

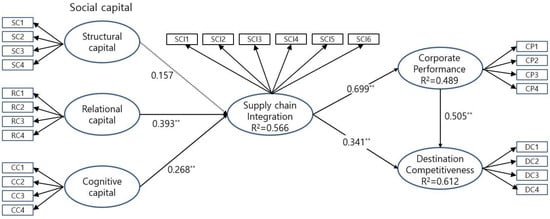

To test H1 to H4, the proposed structural model was assessed using 5000 bootstrap resamples (see Table 6 and Figure 2). The results showed that each relational capital and cognitive capital has positive and significant effect on supply chain integration (β = 0.393, p < 0.01; β = 0.268, p < 0.01, respectively) while construct capital was found to have no significant effect on supply chain integration (β = 0.157, p > 0.05). Therefore, H1 was partially supported.

Table 6.

Results of Hypothesis Testing.

Figure 2.

Results of Structural Model Analysis. Notes: Critical t-values. ** 2.58 (p < 0.01).

Results also showed that supply chain integration has positive and significant effect on both corporate performance (β = 0.699, p < 0.01) and MICE destination competitiveness (β = 0.341, p = 0.000). Moreover, corporate performance was found to have positive and significant effect on MICE destination competitiveness (β = 0.505, p < 0.01). Thus, H2 and H3 was supported. In addition, Table 7 shows the specific indirect effects of variables. As shown in the table, all indirect effects were found to be significant, except the indirect effects of structural capital mediated by supply chain integration on corporate performance (β = 0.110, p > 0.05) and destination competitiveness (β = 0.054, p > 0.05), and the indirect effects of structural capital mediated by supply chain integration and corporate performance on destination competitiveness (β = 0.056, p > 0.05), were found to be insignificant.

Table 7.

Results of Indirect Effects.

We also examined the R2 value of endogenous variables and 56.6% of variance in supply chain integration is explained by social capital (R2 = 0.566) and supply chain integration explains 48.9% of variance in corporate performance (R2 = 0.489) whereas supply chain integration and corporate performance explain 61.2% of variance in MICE destination competitiveness (R2 = 0.612). The R2 values of 0.489 to 0.612 indicate that the proposed structure model shows moderate exploratory power [108]. In addition, the Q2 values of all endogenous variables were found to be above 0 (0.544, 0.482, 0.586, respectively), further supporting the predictive power of the proposed structural model [109].

6. Conclusions

In response to growing recognition of the importance of partnerships among stakeholders as an integral part of sustainable development in the MICE industry, this research explored the impact social capital has in intensifying supply chain integration in the MICE industry as well as the role of supply chain integration in increasing corporate performance and MICE destination competitiveness. The findings reveal that the relational and cognitive dimensions of social capital have a positive influence on supply chain integration. It was also determined that the intensification of supply chain integration leads to higher corporate performance and MICE destination competitiveness. Moreover, the influence of corporate performance on MICE destination competitiveness was confirmed. As such, it can be concluded that relational and cognitive capital are important antecedents to enhancing supply chain integration and that higher corporate performance and MICE destination competitiveness could be the outcomes of increased supply chain integration. The findings of this research can be summarized as follows.

First, among the three dimensions of social capital, only relational and cognitive capital were found to have positive impact on supply chain integration while structural capital did not influence supply chain integration. Such findings suggest that shared trust and understanding among related entities performs important functions in their collaborative relationship. These results may indicate the greater significance of relationships built upon trust, intimacy and/or shared goals, compared to formal and superficial relationships. The result of this research, that only relational and cognitive social capital influences supply chain integration, also builds on the existing knowledge that only some aspects of social capital can influence supply chain integration [54].

Second, the result of this study that increased supply chain integration leads to higher corporate performance confirms the current knowledge that when a supply chain is integrated, performance of the firm can be enhanced [81]. Moreover, the positive influence of supply chain integration on MICE destination competitiveness identified in this research corroborates the argument of previous studies that increased partnerships among stakeholders could trigger an enhancement of destination competitiveness [90].

Lastly, the effect of corporate performance on MICE destination competitiveness confirmed in this research is in line with the relationship outlined in the existing literature regarding how factors such as tourist satisfaction, which is important part of destination competitiveness, can be based on corporate performance [95].

7. Discussion

7.1. Theoretical Implications

The current research bears several theoretical implications, such as the following. First, the finding that social capital and supply chain integration among MICE industry stakeholders enhances MICE destination competitiveness and corporate performance fills the void in the existing literature regarding the communal power of MICE industry stakeholders. While the role of collaborative resources and relationships in yielding positive outcomes for relevant stakeholders has been recognized in general [37], barely any research has explored the collective function in the MICE industry. In line with the proposition of stakeholder theory that entities within a group can achieve higher performance when they collaborate with one another, the result of this study validates the notion that such a proposition can be applied to the MICE industry [9].

This research deepens insights into the type of relationships among stakeholders in the MICE industry. In contrast to attempts in the existing literature that only explored the relationships among limited types of stakeholders, such as CVBs and private companies [46], this research validated the notion that the efforts of various types of stakeholders yields positive outcome. Such a finding suggests that the research subject could be expanded to a comprehensive scope. Going beyond its traditional practice, in the existing literature, of examining the role of only single stakeholders in the MICE industry [29], the current research also underscored the importance of the function of stakeholders on a collective level.

Application of the notions of social capital and supply chain integration in the MICE industry to examining interrelated resources and relationships is a pioneering attempt that promotes solidification of theoretical foundations regarding partnerships in the MICE industry. Departing from the approach of existing studies regarding MICE industry stakeholder relationships and their role explored in case studies and interviews or the examination of the network strength [42,43], this research has empirically verified this linkage. That is, examination of partnerships among them by adopting the well-established concepts of social capital and supply chain integration establishes a theoretically meaningful extension of prior MICE tourism studies.

Moreover, the approach of this study, which employed the concepts of social capital and supply chain integration, extends the current literature on these two notions. While these two concepts have been utilized in the manufacturing industry literature [10], they are yet to be implemented in the MICE industry or other fields extensively. In turn, valid relationships identified among these constructs with other variables in this research confirm that application of social capital and supply chain integration can be extended to other contexts.

The findings of this research also contribute to the current understanding of the variable nature of social capital in regard to its role in influencing supply chain integration. In the context of the MICE industry, social and cognitive capital could serve as the constituents of social capital that help stakeholders to strengthen their collaboration, indicating that the effect of social capital on supply chain integration may vary by context. The impact of the relational and cognitive aspects of social capital on supply chain integration identified in this study also sheds light on the relative value of these two dimensions to structural capital, signifying the aspect of social capital that is important in intensifying the integration of supply chains.

Lastly, the results of this research expand our knowledge regarding the antecedents to the enhancement of MICE destination competitiveness. While existing studies focused on infrastructural aspects of the MICE industry, including transportation, venues, and accommodation [21,23], the results of this study suggest that intangible assets in the MICE industry, such as the resources and collaboration among MICE industry stakeholders, serve as important precursors of MICE destination competitiveness. Thus, such a finding enlarges the list of factors that help to maximize the performance of the MICE industry for the destination.

7.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this research suggest practical insights for tourism and MICE industry practitioners. First, the current study informs practitioners that collaboration among stakeholders is crucial in yielding positive outcomes for MICE industry stakeholders. Specifically, the findings of this research inform industry practitioners that working with others on a collective level is crucial for them to achieve higher firm performance compared to themselves working on their own. Moreover, destination marketers that are interested in enhancing the competitiveness of their destination as a MICE destination should also assist entities in the MICE industry to intensify their partnerships with one another by providing pertinent support. It is also important for governmental organization themselves to work closely with private companies in the MICE industry. Thus, both private companies and governments should recognize its importance and make a collective effort to build close networks among stakeholders.

In building such a cooperative relationship among stakeholders in the MICE industry, the results of this study indicate that shared trust and understanding among the entities involved should be enhanced. Accordingly, collaborative systems or platforms should be established through which stakeholders in the MICE industry can transparently share information and the knowledge they have. For instance, an online platform shared among entities in the MICE industry where they could interact with one another and upload up-to-date information in real time could be effective in promoting an easy and efficient way of facilitating the development of collaborative relationships. Moreover, entities in the MICE industry should make efforts to learn about the needs and work of the others within the industry to build trust and good understanding of others. The government could also reinforce the partnerships by establishing an official committee among stakeholders in the MICE industry through which they could regularly hold a meeting to connect with one another and exchange ideas and latest information. Also, the government could facilitate close interaction among stakeholders by offering seminars and training through which these entities can come together.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This research is not free of limitations. First, the sample of this research is limited to MICE industry stakeholders in Busan, Korea. Future research should be conducted with various samples to verify whether the findings of this research can be extended to stakeholders in different regions. Second, while this study is limited to examining the outcomes of supply chain integration from the perspective of the suppliers, future studies could be conducted from the view of the consumers, in which how collaboration among the suppliers can positively impact consumers could be investigated. For instance, outcome variables such as destination image and behavioral intention could be examined in future studies. Third, while the empirical approach of this study allows enhanced understanding regarding the linkages among social capital, supply chain integration, and its outcomes, such an approach limits our understanding regarding why such a relationship is valid. Thus, qualitative research could be conducted in future to gain an in-depth understanding regarding why collaborative relationships among MICE industry stakeholders lead to positive outcomes for the entities involved as well as for the destination. In addition, although this research attempted to diversify the research sample by collecting data from various types of stakeholders in the MICE industry, the majority of the recruited participants were those who work in venues and PCOs due to the large population of individuals working in these entities compared to others. Future studies should ensure that data is collected as evenly as possible from diverse types of entities. Last, as there could be limitations in applying the data collected from two years ago, future studies should monitor the possible structural changes stakeholders in the MICE industry experience, to ensure that newly added types of stakeholders and changes in structure are considered.

Author Contributions

T.-H.Y.: conceptualization, data collection, writing for methodology, data analysis, and results section; S.W.: writing for introduction, literature review, and conclusion and discussion section. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Grand View Research. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5702112/mice-market-size-share-and-trends-analysis-report (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Kim, I.; Choi, S.; Kim, D.; Choi, N. How long do regional MICE events survive? The case of Busan, Korea. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 807–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spain Travel News. Available online: https://spaintravelnews.co.uk/000519_madrid-is-named-the-worlds-top-mice-destination.html (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Alananzeh, O.; Al-Badarneh, M.; Al-Mkhadmeh, A.; Jawabreh, O. Factors influencing MICE tourism stakeholders’ decision making: The case of Aqaba in Jordan. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2019, 20, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Mason, D.S. The changing stakeholder map of formula one grand prix in Shanghai. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2011, 11, 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, C.K.; Milne, S.; Chi Fai Chui, R. Redefining stakeholder relationships in mega events: New Zealand Chinese and the Rugby World Cup. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2017, 18, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orthodoxou, D.; Loizidou, X.; Gavriel, A.; Hadjiprocopiou, S.; Petsa, D.; Demetriou, K. Sustainable business events: The perceptions of service providers, attendees, and stakeholders in decision-making positions. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2022, 23, 154–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosvold, J.; Rehbein, K.; Barker, P. Predicting board decisions: Are agency theory and resource dependency theory still relevant? Acad. Manag. Proc. 2015, 1, 12155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S. Supply chain integration and Industry 4.0: A systematic literature review. Benchmarking Int. J. 2021, 28, 990–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. The role of social capital in corporations: A review. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2017, 33, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshetnikova, N. The internationalization of the Meetings-, Incentives-, Conventions-and Exhibitions-(MICE) industry: Its influences on the actors in the tourism business activity. J. Econ. Manag. 2017, 27, 96–113. [Google Scholar]

- Sikošek, M. A review of research in meetings management: Some issues and challenges. Acad. Tur. 2012, 5, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, S.A.; Nurul, A.N.; Nurin, U.; Nadiahtul, A.S.; Hassnah, W. Key success factors toward MICE industry: A systematic literature review. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2020, 12, 188–221. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.; Parkash, R. MICE tourism in India: Challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Res. Educ. 2016, 3, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Alananzeh, O.; Al-Mkhadmeh, A.; Shatnawi, H.S.; Masa’deh, R.E. Events as a tool for community involvement and sustainable regional development: The mediating role of motivation on community attitudes. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2022, 23, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Zhu, L. Examining the link between meetings, incentive, exhibitions, and conventions (MICE) and tourism demand using generalized methods of moments (GMM): The case of Singapore. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, G.I.; Del Chiappa, G.; Perdue, R.R. International convention tourism: A choice modelling experiment of host city competition. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, J.S. An exploratory study of factors that exhibition organizers look for when selecting convention and exhibition centers. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 1001–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Kim, H.; Hur, D. Keeping the competitive edge of a convention and exhibition center in MICE Environment: Identification of event attributes for long-run success. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, A. MICE—Future for Business Tourism. Int. J. Adv. Multidiscip. Res. 2016, 3, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, J.K.; Bhalla, N. Factors motivating visitors for attending handicraft exhibitions: Special reference to Uttarakhand, India. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Weber, K. Exhibition destination attractiveness–organizers’ and visitors’ perspectives. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2795–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, N.M.; Ma’amor, H.; Ariffin, N.; Achim, N.A. Servicescape: Understanding how physical dimensions influence exhibitors satisfaction in convention centre. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 211, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Draper, J.; Neal, J.A. Motivations to attend a non-traditional conference: Are there differences based on attendee demographics and employment characteristics? J. Conv. Event Tour. 2018, 19, 347–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Tanford, S. What contributes to convention attendee satisfaction and loyalty? A meta-analysis. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2017, 18, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Niekerk, M.; Getz, D. The identification and differentiation of festival stakeholders. Event Manag. 2016, 20, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.B. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazel, D.; Mason, C. The role of stakeholders in shifting environmental practices of music festivals in British Columbia, Canada. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2020, 11, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S. Event stakeholder management: Developing sustainable rural event practices. Event stakeholder management: Developing sustainable rural event practices. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2011, 2, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adongo, R.; Kim, S. Whose festival is it anyway? Analysis of festival stakeholder power, legitimacy, urgency, and the sustainability of local festivals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1863–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adongo, R.; Kim, S.S.; Elliot, S. “Give and take”: A social exchange perspective on festival stakeholder relations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, G.; Culha, O. Satisfaction and loyalty of festival visitors. Anatolia 2009, 20, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Xing, L.; Chathoth, P.K. The effects of festival impacts on support intentions based on residents’ratings of festival performance and satisfaction: A new integrative approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 316–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Withers, M.C.; Collins, B.J. Resource dependence theory: A review. J. Manag. 2009, 25, 1404–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.D.; Getz, D. Tourism as a mixed industry: Differences between private, public and not-for-profit festivals. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhoff-Isakhanyan, G.; Wubben, E.F.; Omta, S.W. Sustainability benefits and challenges of inter-organizational collaboration in Bio-Based business: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2016, 8, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Marzano, G.; Scott, N. Power in destination branding. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 26, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, T.J. Moving beyond dyadic ties: A network theory of stakeholder influences. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 887–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Krakover, S. Destination marketing: Competition, cooperation or coopetition? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 20, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, F.; Bonetti, E.; Masiello, B. Strong ties within cultural organization event networks and local development in a tale of three festivals. Event Manag. 2012, 16, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiew, F.; Holmes, K.; De Bussy, N. Tourism events and the nature of stakeholder power. Event Manag. 2015, 19, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celuch, K.; Glińska-Neweś, A.; van Niekerk, M. The Cross-Cultural Comparison of Different Communication Styles among Convention and Visitors’bureaus (Cvb). Int. J. Contemp. Manag. 2018, 17, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Lin, Z.; Li, H. Key survival factors in the exhibition industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.R.; Lee, J.S.; Jones, D. Exploring the Interrelationship between Convention and Visitor Bureau (CVB) and its Stakeholders, and CVB Performance from the Perspective of Stakeholders. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 224–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autry, C.W.; Griffis, S.E. Supply chain capital: The impact of structural and relational linkages on firm execution and innovation. J. Bus. Logist. 2008, 29, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, L.; Easton, G. A relational resource perspective on social capital. In Corporate Social Capital and Liability; Leenders, A.J., Gabbay, S.M., Eds.; Kluwer: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 68–87. [Google Scholar]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Tuselmann, H.; Jayawarna, D.; Rouse, J. Effects of structural, relational and cognitive social capital on resource acquisition: A study of entrepreneurs residing in multiply deprived areas. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 31, 534–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allameh, S.M. Antecedents and consequences of intellectual capital: The role of social capital, knowledge sharing and innovation. J. Intellect. Cap. 2018, 19, 858–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claridge, T. Dimensions of Social Capital-structural, cognitive, and relational. Soc. Cap. Res. 2018, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Villena, V.H.; Revilla, E.; Choi, T.Y. The dark side of buyer–supplier relationships: A social capital perspective. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniady, R.A.; Mamum, A.A.; Mohamad, M.R.; Permarupan, P.Y.; Zainol, N.B. The effect of cognitive and relational social capital on structural social capital and micro-enterprise performance. Sage Open 2015, 5, 2158244015611187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.F.; Hund, K.; Tse, D.K. When does guanxi matter? Issues of capitalization and its dark sides. J. Mark. 2008, 74, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, K.V.; Servaes, H.; Tamoyo, A. Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J. Finance 2017, 72, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sözbilir, F. The interaction between social capital, creativity and efficiency in organizations. Think. Ski. Creat. 2018, 27, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basuil, D.A.; Datta, D.K. Value creation in cross-border acquisitions: The role of outside directors’ human and social capital. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Huo, B.; Wang, Z.; Yeung, H.Y. The impact of operations and supply chain strategies on integration and performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 185, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armistead, C.; Mapes, J. The impact of supply chain integration on operatingperformance. Logist. Inf. Manag. 1993, 6, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, E.D.; Roth, A.V.; Dean, J.W., Jr. The influence of an integration strategy on competitive capabilities and business performance: An exploratory study of consumer products manufacturers. J. Oper. Manag. 2003, 21, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayana, S.A.; Pati, R.K.; Vrat, P. Managerial research on the pharmaceutical supply chain–A critical review and some insights for future directions. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2014, 20, 18–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.J.; Handfield, R.B.; Ragatz, G.L. Supplier integration into new product development: Coordinating product, process and supply chain design. J. Oper. Manag. 2005, 23, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudyanto, R.; Soemarni, L.; Pramono, R.; Purwanto, A. The influence of antecedents of supply chain integration on company performance. Uncertain Supply Chain. Manag. 2020, 8, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakurár, M.; Haddad, H.; Nagy, J.; Popp, J.; Oláh, J. The impact of supply chain integration and internal control on financial performance in the Jordanian banking sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Huo, B.; Sun, L.; Zhao, X. The impact of supply chain risk on supply chain integration and company performance: A global investigation. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2013, 18, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setia, P.; Patel, P.C. How information systems help create OM capabilities: Consequents and antecedents of operational absorptive capacity. J. Oper. Manag. 2013, 31, 409–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.W.; Wong, C.Y.; Boon-Itt, S. The combined effects of internal and external supply chain integration on product innovation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 146, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, B. The impact of supply chain integration on company performance: An organizational capability perspective. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.; Irani, Z. Analysing supply chain integration through a systematic literature review: A normative perspective. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2014, 19, 523–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnandavar, C.M.; Wong, W.P.; Soh, K.L. Dynamics of supply environment and information system: Integration, green economy and performance. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 62, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durach, C.F.; Wiengarten, F. Supply chain integration and national collectivism. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 224, 107543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, P.; Scheffler, P.; Schiele, H. Internal integration as a pre-condition for external integration in global sourcing: A social capital perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 153, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ye, F.; Sheu, C. Social capital, information sharing and performance: Evidence from China. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 1440–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Huo, B. The impact of dependence and trust on supply chain integration. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2013, 43, 544–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambasivan, M.; Siew-Phaik, L.; Mohamed, Z.A.; Leong, Y.C. Factors influencing strategic alliance outcomes in a manufacturing supply chain: Role of alliance motives, interdependence, asset specificity and relational capital. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 141, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, B.; Leem, B. The effect of the supply chain social capital. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2013, 113, 324–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, Z.M. Social capital influence on supply chain integration in the food processing industry in Malaysia. J. Int. Bus. Econ. Entrep. 2017, 2, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipu, S.A.; Fantazy, K. Exploring the relationships of strategic entrepreneurship and social capital to sustainable supply chain management and organizational performance. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2018, 67, 2046–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataseven, C.; Nair, A. Assessment of supply chain integration and performance relationships: A meta-analytic investigation of the literature. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 185, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, H.; Wei, S.; Gu, J. Top managers’ managerial ties, supply chain integration, and firm performance in China: A social capital perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 74, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenherr, T.; Swink, M. Revisiting the arcs of integration: Cross-validations and extensions. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, M.; Barratt, R. Exploring internal and external supply chain linkages: Evidence from the field. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siagian, H.; Tarigan, Z.J.; Jie, F. Supply chain integration enables resilience, flexibility, and innovation to improve business performance in COVID-19 era. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittichainuwat, B.; Laws, E.; Maunchontham, R.; Rattanaphinanchai, S.; Muttamara, S.; Mouton, K.; Lin, Y.; Suksai, C. Resilience to crises of Thai MICE stakeholders: A longitudinal study of the destination image of Thailand as a MICE destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinay, L.; Kozak, M. Revisiting destination competitiveness through chaos theory: The butterfly competitiveness model. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronjé, D.F.; Du Plessis, E. A review on tourism destination competitiveness. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L. Destination Competitiveness and Resident Well-Being. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, G.I.; Ritchie, J.B. Tourism, competitiveness, and societal prosperity. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvasnová, D.; Gajdošík, T.; Maráková, V. Are partnerships enhancing tourism destination competitiveness? Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2019, 67, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufteros, X.A.; Rawski, G.E.; Rupak, R. Organizational integration for product development: The effects on glitches, on-time execution of engineering change orders, and market success. Decis. Sci. 2010, 41, 49–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Research note: Quality of government and tourism destination competitiveness. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, E.; Ehsani, M.; Saffari, M.; Norouzi, R. How can destination competitiveness play an essential role in small island sports tourism development? Integrated ISM-MICMAC modelling of key factors. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 6, 1222–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.R.; Crouch, G.I. The competitive destination: A sustainability perspective. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, S.; Ivanova, M. Do hotel chains improve destination’s competitiveness? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 19, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, D.; Stoeckl, N.; Liu, H.B. The impact of economic, social and environmental factors on trip satisfaction and the likelihood of visitors returning. Tour Manag. 2016, 52, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.; Elliott, D.; Drake, P. Exploring the role of social capital in facilitating supply chain resilience. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2013, 18, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, R.; Jayaram, J. Causal linkages in supply chain management: An exploratory study of North American manufacturing firms. Decis. Sci. 1998, 29, 579–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, H.; Sundarakani, B.; Vel, P. The impact of implementing green supply chain management practices on corporate performance. Comp. Rev. 2016, 26, 216–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Choi, Y.; Breiter, D. An exploratory study of convention destination competitiveness from the attendees’ perspective: Importance-performance analysis and repeated measures of MANOVA. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 40, 589–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B.; Wang, S.; Fu, X.; Yi, X. Beyond local food consumption: The impact of local food consumption experience on cultural competence, eudaimonia and behavioral intention. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Pick, M.; Liengaard, B.D.; Radomir, L.; Ringle, C.M. Progress in partial least squares structural equation modeling use in marketing research in the last decade. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1035–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M. Common beliefs and reality about partial least squares: Comments on rönkkö & evermann. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.G.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Discriminant validity assessment in PLS-SEM: A comprehensive composite-based approach. Data Anal. Perspect. J. 2022, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).