Abstract

This study aims to explore how work disengagement (WD) is affected by employees’ perceptions of distributive injustice (DI). It also investigates the mediating roles of workplace negative gossip (WNG) and organizational cynicism (OC). Responses were received from the full-time employees of category (A) travel agencies and five-star hotels operating in Egypt. WarpPLS 7.0 was used to run a PLS-SEM analysis on the 656 valid responses. The results revealed that there is a positive relationship between employees’ perception of distributive injustice and work disengagement level; in addition, there is a positive relationship between perception of distributive injustice and workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism. Results also reported positive relationships between workplace negative gossip, organizational cynicism, and work disengagement. Furthermore, findings showed that workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism mediate the relationship between distributive injustice and work disengagement. Some groundbreaking investigations were conducted as part of the research. Research on how DI affects WNG, OC, and WD is still lacking. In terms of contextual significance, an empirical investigation of the relationship between these factors in hotels and travel companies is unavailable. By empirically examining these connections in the context of Egyptian hotels and travel agencies, the current study has filled a gap in the literature on tourism and hospitality, human resources management, and organizational behavior.

1. Introduction

In organizational contexts, distributive injustice pertains to the perception of unfairness in the distribution of resources or rewards, and it can significantly impact employee attitudes and behaviors [1]. This occurs when employees perceive inequitable treatment in terms of tangible benefits they receive, including pay, promotions, bonuses, recognition, and opportunities. The experience of distributive injustice can evoke negative emotions such as resentment, frustration, and dissatisfaction among employees [2]. Fairness, according to Adams [3], relates to how much individuals are aware of and compare their conditions to those of others. People would try to ensure fairness by comparing the inputs (and outputs) brought to (and received from) the same behavior by others. People may regard the given scenario as fair as long as the ratio of these inputs and outcomes is equal. Furthermore, organizations that prioritize distributive justice considerations tend to have employees who are motivated and actively involved in their work. Resolving issues related to distributive injustice requires implementing transparent and fair reward systems, providing equal opportunities for promotions, and consistently acknowledging the contributions of employees. Neglecting to address distributive injustice can result in reduced job engagement, increased employee turnover rates, and an adverse effect on overall organizational performance [4]. One negative outcome that can arise from distributive injustice is work disengagement, which is characterized by a lack of motivation, detachment, and disinterest in one’s job. It is important to comprehend the underlying mechanisms through which distributive injustice impacts work disengagement to develop effective interventions and enhance employee well-being [5,6].

In response to perceived distributive injustice, employees may exhibit various behaviors such as reduced effort, diminished cooperation, increased absenteeism, participation in negative workplace gossip, the development of organizational cynicism, and even turnover [7,8]. Studies have indicated that distributive injustice can create an environment conducive to negative gossip and contribute to a culture of cynicism within the organization [9]. When employees sense inequity in the allocation of rewards or resources, they may resort to engaging in negative gossip as a means to cope with their feelings of injustice or to seek social support from their colleagues [10].

Additionally, encountering distributive injustice can undermine employees’ trust and faith in the organization, resulting in heightened cynicism [9,11]. The prevalence of negative gossip can serve as an indicator of the organizational culture and atmosphere. When negative gossip is pervasive and accepted, it can contribute to a toxic work environment characterized by diminished morale, elevated conflict, fear, discomfort, insecurity, reduced work engagement, and decreased productivity [12].

During times of change or transformation, organizational cynicism can present obstacles. Employees who harbor cynicism may resist or undermine change initiatives due to their skepticism regarding the organization’s intentions or the perceived ineffectiveness of past changes. This resistance can impede the organization’s capacity to adapt and address evolving market conditions or industry trends. Cynical employees are less likely to be actively engaged in their work and committed to the organization. They may demonstrate reduced levels of discretionary effort and be more inclined to consider leaving the organization [13,14].

The presence of pervasive cynicism within an organization can generate an unfavorable work environment, deterring high-performing employees and posing challenges to attracting and retaining top talent [15]. Both negative workplace gossip and organizational cynicism have been linked to work disengagement. Negative gossip can foster a toxic work environment, erode trust, and hinder collaboration, ultimately resulting in disengagement [16]. Similarly, organizational cynicism is associated with decreased motivation, diminished job satisfaction, and reduced commitment to the organization, all contributing factors to work disengagement [17,18].

Although the relationship between distributive injustice and work disengagement has been investigated in various industries [6,19], there is a research gap when it comes to examining this relationship specifically within the context of the tourism and hospitality sectors. Furthermore, the mediating factors of workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism have not been extensively explored. There is a need to understand how distributive injustice significantly impacts work disengagement within the tourism and hospitality industries. While studies conducted in other sectors have examined the influence of distributive injustice on work disengagement, the unique characteristics of the tourism and hospitality business, such as customer interactions, service quality, and emotional labor, may require a customized approach to better comprehend this relationship.

Therefore, there is a clear research imperative to investigate the ramifications of distributive injustice within the tourism and hospitality industries. Another research gap exists in comprehending the mediating mechanisms of workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism. While previous studies have separately explored the link between distributive injustice and work disengagement, as well as the influence of workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism on work disengagement, no prior research has examined the mediating effects of workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism specifically within the tourism and hospitality sectors in the context of the relationship between distributive injustice and work disengagement. Consequently, the present study aims to bridge this gap by pursuing three primary objectives: (1) assessing the impact of distributive injustice on organizational negative gossip, organizational cynicism, and work disengagement; (2) evaluating the influence of workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism on work disengagement; and (3) examining the mediating role of workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism between distributive injustice and work disengagement.

Obtaining a comprehensive understanding of how distributive injustice influences work disengagement necessitates gaining insight into the interrelationships among these variables. Addressing these research gaps is of utmost importance to advance knowledge in the field of organizational injustice and its impact on work disengagement, specifically within the tourism and hospitality sectors. By bridging these gaps, researchers can provide evidence-based recommendations to organizations in this industry, enabling them to foster supportive work environments that mitigate workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism and reduce levels of work disengagement. The problem raised by the current study is even more of a concern in the tourism and hospitality industries, which are labor-intensive and employ a large number of people while also heavily depending on natural resources [20,21]. The tourism and hospitality business is also known for its fast-paced and dynamic nature, which requires staff to overcome a variety of challenges while providing great customer service [22]. To boost employee outcomes in this context, a work environment that creates a constructive working climate is required.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Distributive Injustice

Distributive injustice pertains to the perception of unfairness in how rewards, resources, or outcomes are distributed within an organization. It occurs when individuals believe that they are not receiving a fair share of rewards or benefits concerning their contributions, efforts, or the contributions of others. This perception of unfair treatment can result in negative emotional responses and dissatisfaction among employees [23,24]. In situations where distributive injustice is present, employees may perceive that others receive more favorable treatment or rewards despite having similar or even lesser contributions [25]. This perception can evoke feelings of resentment, demotivation, and a diminished sense of commitment to the organization [26]. Distributive injustice can impact various aspects of the workplace, including morale, interpersonal relationships, and the overall organizational culture [27].

2.2. Workplace Negative Gossip

Workplace negative gossip refers to the dissemination of unfavorable or derogatory information or rumors about individuals or events within an organizational context. It entails the informal sharing of critical or malicious comments about colleagues, supervisors, or the organization itself [28,29]. Typically, negative gossip occurs through informal communication channels such as casual conversations, social interactions, or electronic communication platforms, bypassing formal channels of communication within the organization [30]. Negative gossip encompasses various topics, including personal information, performance-related issues, conflicts, or rumors about organizational changes. It tends to emphasize negative aspects by highlighting the weaknesses, mistakes, or undesirable behaviors of individuals or groups [31].

Negative gossip targeted at an individual can have adverse impacts on their overall well-being and professional connections [32]. It can generate stress, anxiety, and feelings of isolation or exclusion. Moreover, the dissemination of negative gossip can undermine trust and foster a hostile work environment, thereby impeding collaboration and teamwork [33]. Furthermore, individuals who actively participate in negative gossip may also experience undesirable outcomes, including harm to their reputation or strained relationships with colleagues. The consequences of workplace negative gossip extend beyond the individuals involved and can have significant implications for the organization as a whole [34,35]. It has the potential to foster a toxic work culture marked by negativity, suspicion, and conflict. The negative atmosphere fueled by gossip can diminish overall job satisfaction, dampen employee morale, and weaken organizational commitment [29,36].

2.3. Organizational Cynicism

Organizational cynicism refers to the adoption of a negative attitude or perception by employees toward their organization. It is characterized by skepticism, distrust, and the belief that the organization’s actions, intentions, or decisions are primarily motivated by self-interest, dishonesty, or a lack of integrity [27,37]. The presence of organizational cynicism can manifest in various ways and have an impact on employee attitudes, behaviors, and the overall climate within the organization [38]. Employees often develop organizational cynicism as a result of negative experiences, perceptions of injustice, or a series of disappointing events within the organization [39].

Cynicism within an organization can be attributed to various factors, including perceived inequities, lack of transparency, broken promises, unethical behavior, poor leadership, organizational changes, and perceived organizational hypocrisy [40]. The presence of organizational cynicism undermines trust between employees and the organization, as well as among employees themselves [17]. It impedes collaboration, teamwork, and effective communication, resulting in reduced cooperation and limited knowledge sharing. When cynicism becomes widespread within an organization, it contributes to a negative organizational culture characterized by low morale, the spread of cynicism among employees, and a lack of enthusiasm. Furthermore, it hampers innovation, adaptability, and efforts towards organizational change [41,42].

2.4. Work Disengagement

Work disengagement, also known as employee disengagement or workplace disengagement, refers to a condition where employees experience a sense of disconnection, lack of involvement, and disinterest in their jobs and the organization they belong to. It is characterized by diminished motivation, decreased enthusiasm, and a general feeling of indifference towards their work and the workplace environment [43,44]. The presence of work disengagement can have negative consequences for both individual employees and the organization as a whole [45].

Disengaged employees tend to display a lack of passion and interest in their job responsibilities. They may fulfill their duties without experiencing a sense of satisfaction or commitment [46]. Disengagement is frequently accompanied by a decline in the level of effort employees put into their work, resulting in reduced productivity and lower-quality outcomes [47]. Disengaged employees may also emotionally detach themselves from their work, colleagues, and the organization as a whole. They may not feel personally invested in the success of the organization or their role within it [48]. Work disengagement has the potential to result in a decline in job performance, as employees are less inclined to exceed their basic job requirements or contribute to innovative solutions. This disengagement can hinder progress towards organizational goals and objectives [6].

2.5. Social Exchange Theory

The application of Social Exchange Theory is crucial for comprehending the intermediary functions of workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism in the relationship between distributive injustice and work disengagement within the tourism and hospitality industries. This theory highlights the importance of reciprocal relationships, where individuals anticipate fair exchanges of resources, benefits, and contributions [49,50].

Social Exchange Theory suggests that individuals engage in relationships and interactions with an inherent expectation of reciprocity [51,52]. Distributive injustice disrupts this reciprocal exchange by creating a perception of inequity in the distribution of efforts and rewards. Employees who perceive distributive injustice may experience a breach in the social contract that forms the foundation of their relationship with the organization [53]. Negative gossip can be viewed as a form of social currency within an organizational context [54,55].

As a response to perceived distributive injustice, employees may resort to engaging in negative gossip as a means to exchange information and express their frustrations. Through sharing negative information about others, employees may seek validation for their negative emotions, thus establishing a temporary sense of social balance [56,57].

Negative gossip can serve as a means for employees to communicate their dissatisfaction with perceived unfair treatment [58,59]. Through the sharing of negative information about the organization, its decisions, or colleagues, employees can express their discontent without directly confronting those they hold responsible for the perceived injustice [60]. Perceived breaches in the social exchange relationship can give rise to organizational cynicism [61]. When employees believe that the organization fails to fulfill its obligations in providing equitable rewards, they may develop cynical attitudes [62].

Cynicism can function as a defense mechanism employed by employees to shield themselves from additional disappointment and unfulfilled expectations [63]. Work disengagement can be interpreted as a disengagement from the process of social exchange [64]. When employees perceive that the organization is failing to fulfill its obligations in the reciprocal relationship, they may emotionally and behaviorally detach themselves from their work. Disengagement can be a strategy to restrict further investment in a relationship that is perceived as unjust [65].

Trust and reciprocity play crucial roles in maintaining relationships, as emphasized by Social Exchange Theory. Distributive injustice undermines trust in the organization’s commitment to fulfill its obligations within the exchange relationship [66]. In response to this breach of trust, negative gossip and organizational cynicism may arise, exacerbating the reluctance to engage in reciprocal behaviors [67].

2.5.1. The Relationship between Distributive Injustice and Work Disengagement

When employees perceive a sense of inequity, they typically respond with both emotional and cognitive reactions [68]. Negative emotions such as frustration, resentment, and disillusionment emerge, eroding their emotional connection to their work and the organization [69]. This emotional response can trigger cognitive dissonance, which occurs when there is a discrepancy between the perceived injustice and their values and expectations, resulting in internal conflict [70].

In terms of cognition, employees undergo a process of reevaluating their dedication to the organization. They begin to question the fairness of their work environment and the ethical standards upheld by the organization. This questioning process can result in a reduced sense of identification with the organization’s goals and values, ultimately contributing to diminished work engagement [71,72]. Employees who perceive distributive injustice may start perceiving their work as merely transactional rather than a meaningful contribution, leading to decreased levels of enthusiasm and effort invested in their tasks [73].

In terms of behavior, the effects of distributive injustice are evident in the form of work disengagement [6,74]. Employees exhibit reduced motivation to go beyond their assigned duties, resulting in decreased productivity and creativity [75]. This disengagement can manifest as missed deadlines, lower-quality work, and diminished collaboration with colleagues. Additionally, employees may socially disengage from the workplace, leading to decreased interactions with coworkers and limited participation in team activities [76].

Furthermore, distributive injustice can have adverse consequences for employees’ perceptions of organizational justice. Organizational justice encompasses the overall fairness of procedures, interactions, and outcomes within the organization. When employees perceive distributive injustice, it can result in a perception of low organizational justice as a whole, which, in turn, contributes to work disengagement. Employees may begin to question the organization’s legitimacy and integrity, leading to decreased commitment and motivation to contribute to its goals [77,78].

Likewise, the negative emotional reactions elicited by distributive injustice can exacerbate work disengagement [74]. Employees who perceive unfair treatment may experience negative emotions such as anger, resentment, or a sense of being undervalued. These negative emotions can impede their capacity to fully engage in their work and may result in reduced effort or diminished enthusiasm [19]. Hence, we hypothesize the following:

H1.

Distributive injustice is positively linked to work disengagement.

2.5.2. The Relationship between Distributive Injustice and Workplace Negative Gossip

The connection between distributive injustice and negative workplace gossip is defined by the influence of perceived unfairness on cultivating a gossip culture within the organization [58]. Distributive injustice has the potential to elicit negative emotions like anger, resentment, or frustration among employees who perceive themselves as being treated unfairly. These negative emotions can drive individuals to seek validation and support from their colleagues [60]. Negative gossip can function as a means for employees to communicate their discontent, express grievances, and seek camaraderie with others who share similar experiences or perceive unfairness. It can serve as an outlet for venting frustration and seeking a sense of justice or validation [79].

Within the workplace, negative gossip has the potential to rapidly disseminate, driven by the emotions and perceptions connected to distributive injustice [58]. Employees may partake in informal conversations, discussions, or information exchanges that center around highlighting instances of perceived unfairness or negative encounters regarding the distribution of rewards. This can perpetuate a cycle of negative gossip as individuals share their narratives and experiences and ultimately contribute to the development of an unfavorable work environment characterized by mistrust, rumors, and conflicts [80]. Negative gossip functions as a coping mechanism utilized in response to the emotional distress triggered by distributive injustice [81]. Employees may experience a sense of powerlessness when it comes to addressing perceived inequalities directly, and negative gossip serves as a means to indirectly influence the perception of those in positions of power [82].

Distributive injustice triggers social comparison processes among employees [83]. When individuals observe unfairness in the allocation of rewards, they engage in social comparisons, comparing their outcomes to those of others [84]. Negative gossip can function as a form of solidarity among employees who perceive themselves as victims of distributive injustice. It cultivates a sense of camaraderie and shared grievances, forging a bond among those who believe they have been treated unfairly [85]. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H2.

Distributive injustice is positively linked to workplace negative gossip.

2.5.3. The Relationship between Workplace Negative Gossip and Work Disengagement

The correlation between workplace negative gossip and work disengagement is characterized by the detrimental effects of gossip on employees’ motivation, job satisfaction, and overall work engagement [86]. At the core of this relationship is the function of workplace negative gossip as a catalyst for negative emotions and perceptions. When employees engage in or are exposed to negative gossip, it can foster a toxic emotional environment. The negative nature of gossip, typically centered around grievances or perceived injustices, elicits feelings of dissatisfaction, mistrust, and cynicism [87].

Negative gossip within the workplace cultivates an unfavorable emotional atmosphere that can adversely impact employees. Consistent exposure to negative gossip can result in heightened stress, anxiety, and a sense of insecurity. These negative emotions can deplete employees’ energy and diminish their enthusiasm, leading to reduced motivation to wholeheartedly engage in their work [58,88].

In addition, negative gossip in the workplace can serve as a distracting force that redirects employees’ focus away from their work tasks and objectives. Participating in or being exposed to gossip can consume precious time and mental resources that should be dedicated to productive work. The persistent preoccupation with gossip can disrupt workflow, impede concentration, and contribute to decreased productivity and engagement [89].

The existence of widespread negative gossip can foster a toxic work environment marked by distrust, fear, and prevailing negativity. According to Robinson and Bennett [90], deviant workplace behavior may be anticipated in part by an organization’s ethical atmosphere. Employees who perceive their work environment as toxic may experience feelings of demoralization, undervaluation, and lack of support, leading to disengagement. The continuous presence of negative gossip perpetuates a culture that undermines motivation and engagement [34]. Hence, we hypothesize the following:

H3.

Workplace negative gossip is positively linked to work disengagement.

2.5.4. The Mediating Role of Workplace Negative Gossip between Distributive Injustice and Work Disengagement

Employees who perceive distributive injustice may develop a sense that they are being treated unfairly or that their contributions are not adequately recognized. This perception can arise from disparities in rewards, promotions, or opportunities for advancement. Experiencing distributive injustice triggers negative emotions, including frustration, resentment, and anger [2,91]. In response to distributive injustice, employees may resort to negative gossip as a way to vent their frustrations and seek validation from others who have encountered similar situations [92].

Negative gossip serves as a means for employees to express their perceptions of unfairness, discuss instances of inequity, and release their emotions. It becomes a coping mechanism for employees to deal with the negative feelings linked to distributive injustice. Workplace negative gossip reinforces and intensifies the negative emotions associated with distributive injustice. As employees participate in gossip and exchange negative accounts, it sustains a cycle of negativity, intensifying the negative emotions experienced. Continuous exposure to negative gossip can exacerbate feelings of discontentment, anger, and disengagement among employees [34,81,82].

The interaction between distributive injustice and workplace negative gossip can contribute to work disengagement. Employees who encounter distributive injustice and are exposed to negative gossip are prone to feeling demoralized, undervalued, and disconnected from their work. Disengagement may manifest as diminished motivation, decreased productivity, and a lack of commitment to organizational objectives [58,93]. Distributive injustice can generate a perception of limited control and influence over one’s work outcomes [94]. When employees perceive that their rewards and opportunities are determined arbitrarily or influenced by factors beyond their control, it diminishes their sense of autonomy and can lead to disengagement. Negative gossip serves as a means for employees to express their perceived lack of control and vent their frustrations, thereby reinforcing the belief that they have minimal influence over their work situation [95].

Negative gossip acts as a mediator, indicating that the emotional responses evoked by distributive injustice are communicated through informal channels. These negative emotions can contribute to the emergence of work disengagement [58]. As employees partake in negative conversations and express their perceptions, the collective dissatisfaction may foster a negative work environment, undermine trust in the organization, and ultimately result in disengagement [96]. Accordingly, we hypothesize the following:

H4.

Workplace negative gossip mediates the link between distributive injustice and work disengagement.

2.5.5. The Relationship between Distributive Injustice and Organizational Cynicism

Experiencing distributive injustice can foster the growth of organizational cynicism within employees. This can manifest as a cynical perspective where employees perceive the organization as self-serving, manipulative, and indifferent to their well-being. They may hold the belief that decisions about rewards, promotions, and resource allocation are influenced by favoritism, politics, or hidden agendas rather than being guided by principles of fairness and merit [27,97].

Employees view organizational events and behaviors through a cynical filter, assuming that any perceived injustice or unfavorable outcomes are intentional efforts by the organization to exploit or mistreat them. This biased interpretation reinforces their cynical beliefs and perpetuates negative attitudes [98]. Central to this connection is the emotional reaction to distributive injustice. When employees perceive unfair treatment regarding rewards or opportunities in comparison to their colleagues, they feel a sense of inequity, frustration, and disillusionment. These negative emotions can undermine their trust in the organization’s dedication to fairness and their faith in its integrity. The erosion of trust forms the basis for the development of organizational cynicism [94].

The connection between distributive injustice and organizational cynicism is reinforced by cognitive biases. Employees who perceive distributive injustice tend to focus on and remember information that aligns with their negative beliefs about the organization. This confirmation bias can intensify their cynicism, causing them to interpret even neutral or positive organizational actions as indications of hidden agendas [27]. Hence, we hypothesize the following:

H5.

Distributive injustice is positively linked to organizational cynicism.

2.5.6. The Relationship between Organizational Cynicism and Work Disengagement

Negative attitudes and perceptions towards the organization are linked to organizational cynicism [99]. Employees who hold a cynical outlook tend to harbor negative views of the organization and its leadership, interpreting their actions as self-serving or driven by concealed motives. This negative perception acts as a psychological barrier that obstructs employees’ emotional connection and identification with the organization [100].

Employees who hold cynical attitudes are prone to displaying decreased motivation and effort in their work [101]. The perception that the organization prioritizes self-interest over the well-being of its employees diminishes their sense of purpose and intrinsic motivation. As a result, they may become less engaged in their work, resulting in a decline in the quality and quantity of their contributions [102].

Organizational cynicism has the potential to contribute to emotional exhaustion and burnout among employees. The negative and skeptical mindset associated with cynicism demands continuous cognitive and emotional exertion. This prolonged effort can deplete employees’ energy and resources, resulting in feelings of exhaustion and a diminished capacity to cope with work-related stressors. Consequently, employees may disengage from their work as a means of self-preservation [103,104,105].

Work disengagement frequently presents itself through various withdrawal behaviors [106]. Cynical employees may demonstrate these behaviors by participating less in team activities, reducing collaboration with colleagues, or avoiding additional responsibilities. They may also physically withdraw by frequently taking sick leave, arriving late, or leaving early. These withdrawal behaviors signify a diminished commitment and decreased dedication to the organization and its objectives [107,108].

Employees’ perceptions of the value of their work can be influenced by organizational cynicism. When employees perceive that their organization’s main driving force is self-interest rather than a genuine commitment to its employees, they may begin to doubt the importance of their contributions [109]. This skepticism regarding the organization’s underlying motivations can result in a decreased sense of purpose and satisfaction in their roles, ultimately contributing to work disengagement [110]. Hence, we hypothesize the following:

H6.

Organizational cynicism is positively linked to work disengagement.

2.5.7. The Mediating Role of Organizational Cynicism between Distributive Injustice and Work Disengagement

Organizational cynicism can serve as a channel through which the negative emotions arising from distributive injustice are channeled. Cynical employees may express their discontent through sarcasm, distrust, and skepticism, thereby creating a self-reinforcing cycle that sustains their negative attitudes. This perpetuation of cynicism can contribute to work disengagement, as employees may disengage from their roles due to their perceived lack of trust in the organization’s motives [111,112].

Organizational cynicism acts as an intermediary between distributive injustice and work disengagement. When employees encounter distributive injustice, it generates a negative view of the organization, its leaders, and its decision-making procedures [113]. This negative perception subsequently leads to organizational cynicism, which encompasses skepticism, mistrust, and the belief that the organization’s actions are primarily driven by self-interest [100].

Perceptions of distributive injustice can lead to organizational cynicism, which in turn has a significant impact on work disengagement among employees [97]. Cynical employees may disengage from their work as a coping mechanism or in response to their negative views of the organization. This disengagement can result in reduced motivation, diminished commitment, and a lack of enthusiasm towards work-related tasks [105]. The consequences of work disengagement may include decreased productivity, lower work quality, and a lack of proactive behaviors [106].

A decline in employees’ trust in the organization and its leaders can be attributed to organizational cynicism [114]. The perception of distributive injustice erodes trust and fosters skepticism regarding the organization’s fairness and intentions. This diminished trust can then lead to work disengagement, as employees may become less motivated to devote their time, effort, and energy to their work [17,115].

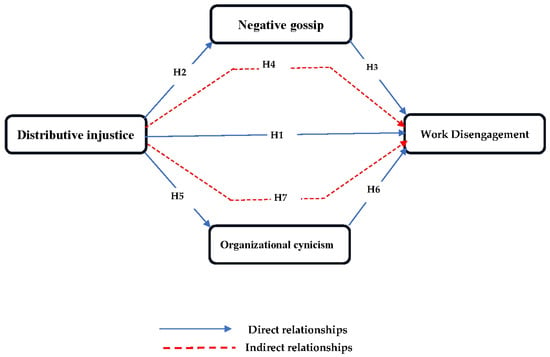

Negative emotions such as anger, resentment, and disillusionment are triggered by distributive injustice experienced by employees [116]. These emotions play a significant role in the emergence of organizational cynicism. When employees perceive distributive injustice, they may experience feelings of betrayal or unfairness, which intensify their cynicism towards the organization [97]. The emotional responses associated with distributive injustice contribute to the formation and reinforcement of organizational cynicism, subsequently impacting work disengagement [117]. Therefore, we hypothesize the following (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

The hypothesized research framework.

H7.

Organizational cynicism mediates the link between distributive injustice and work disengagement.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measures and Instrument Development

The survey employed in this study was split into a pair of parts. The first asks for four latent variables examined in the study, namely, distributive injustice, work disengagement, negative workplace gossip, and organizational cynicism. This part included 30 items. The second part of the survey asked five questions for employees about their gender, age, education, years of working experience, and work organization. Distributive injustice was assessed on a 4-item scale [118]. For example, “In a hotel/travel agency, the outcome process does not reflect the effort I have put into my work” and “In a hotel/travel agency, the outcome process is unjustified, given my performance”. In addition, employees’ work disengagement was evaluated by a 9-item scale [119]. Sample items included: “When I get up in the morning, I do not feel like going to work” and “I do not feel happy when I am working intensely”. Furthermore, negative workplace gossip was measured by a 10-item scale adapted from [120]. For instance, “I questioned a co-worker’s abilities while talking to another work colleague” and “I vented to a work colleague about something that your supervisor has done”. Moreover, organizational cynicism was assessed on a 7-item scale [121]. For example, “Suggestions on how to solve problems around here will not produce much real change” and “Hotel/travel agency’s management is more interested in its goals and needs than in its employees’ welfare”. The complete scale of items is outlined in Appendix A. The original survey was created in English. Furthermore, a back-translation approach was adopted to translate into Arabic and ensure that matching was achieved. All participants’ replies were evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale “ranging from 1 for strongly disagreeing to 5 for strongly agreeing”.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

The research model was evaluated using information acquired from staff members at Egypt’s category (A) travel agencies and five-star hotels from March 2023 to May 2023. Working at category (A) travel agencies and a five-star hotel is demanding since they strive to provide high-quality services to their consumers at all times. Employees in those organizations are more likely to engage in frequent disagreements and unethical behaviors, such as negative gossip and cynicism, due to the hard workload and demands of their positions [122]. According to the 2018 statistics provided by the ministry of tourism, Egypt has 2222 category (A) travel agencies and 158 5-star hotels. The convenience sample strategy was adopted due to the geographical breadth of this study and the fact that the five-star hotels and travel firms were dispersed throughout Egypt. Approximately 1000 questionnaires were delivered to the organizations under investigation. Only 656 valid forms were obtained, representing a 65.6% response rate; 450 (68.6%) surveys were gathered from 30 five-star hotels, and 206 (31.4%) responses were received from 50 category (A) travel agencies. The entire number of employees working in category (A) travel agencies and five-star hotels in Egypt is not disclosed in any official statistics. As a consequence, the sampling equation [123] was utilized in this study. When a list of populations is unavailable, such as in the current study, Cochran [123] devised an equation to provide a representative sample for the population that equals 385 responses. As a result, the 656 valid replies gathered were adequate for the final analysis.

3.3. Data Analysis

To investigate the study’s measurement and structural model, as well as to validate the research hypotheses, the current study used the PLS-SEM approach with WarpPLS software version 7.0. PLS-SEM is a commonly utilized analytical approach in tourism and hospitality research [124].

4. Results

4.1. Participant’s Characteristics

Out of 656 respondents, there were 520 (79.3%) male respondents and 136 (20.7%) female respondents. In addition, 254 (38.7%) of respondents were under the age of 30, 316 (48.2%) between the ages of 30 and less than 40, and 86 (13.1%) between the ages of 40 and more than 50. Moreover, 106 (16.2%) held a high school or high institute certificate, compared to 528 (80.5%) who held a bachelor’s degree and 22 (3.4%) who held a master’s or Ph.D. degree. Furthermore, 292 (44.5%) had more than ten years of work experience, whereas 122 (18.6%) had less than two years, 132 (20.1%) had two to five years, and 110 (16.8%) had six to ten years. In addition, 450 (68.6%) of respondents worked in five-star hotels, while 206 (31.4%) worked in the travel agency category (A). Please see detail in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant’s profile (N = 656).

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Factor Loadings

According to Table 2, factor loading was calculated and indicated that item loadings ranged between 0.534 and 0.858. Factor loading values greater than 0.5 are considered acceptable, according to [125] criteria. Table 2 also showed that the mean scores of distributive injustice, work disengagement, negative workplace gossip, and organizational cynicism as reported by hotel and travel agency employees were (3.09 ± 1.04), (3.55 ± 0.89), (3.47 ± 0.98), and (3.06 ± 0.99), respectively.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and factor loadings.

4.3. Reliability and Validity

When all variables are greater than 0.7, as shown in Table 3, ref. [126] claims that Cronbach alpha and composite reliability for all variables are satisfactory. Additionally, AVE values greater than 0.5 were found, indicating the validity of the scales [124]. All Full-Collinearity VIF scores were satisfactory as well.

Table 3.

Reliability and AVEs.

In addition, a discriminant validity test was performed. Table 4 demonstrates that the AVE value is larger than the highest common value for each variable. These findings, according to Hair et al. [124], validate the study model’s reliability and validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity results.

4.4. Model Fit and Quality Indices for the Research Model

Before testing hypotheses, model fit had been verified. All model fit and quality index findings meet the criteria, as indicated in Appendix B.

4.5. The Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

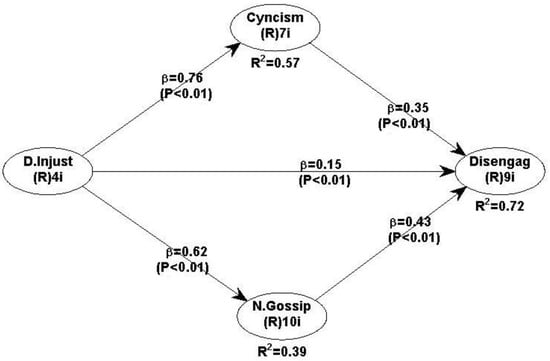

The structural model of the study was examined using path coefficient analysis (β), p-value, and R-square (R2). The hypotheses testing findings (Figure 2 and Table 5) show that there is a positive relationship between distributive injustice and work disengagement (β = 0.15, p < 0.01), negative workplace gossip (β = 0.62, p < 0.01), and organizational cynicism (β = 0.76, p < 0.01). This means that distributive injustice increases work disengagement, negative workplace gossip, and organizational cynicism. Therefore, H1, H2, and H5 are supported. In addition, a positive relationship existed between negative workplace gossip, organizational cynicism, and work disengagement (β = 0.35, p < 0.01) and (β = 0.43, p < 0.01), respectively. This means that negative workplace gossip and organizational cynicism increase work disengagement. Therefore, H3 and H6 are supported.

Figure 2.

The final model of the study.

Table 5.

Mediation analysis (Bootstrapped Confidence Interval).

Additionally, Figure 2 shows that distributive injustice interpreted 39% of the variance in negative workplace gossip (R2 = 0.39) and 57% of the variance in organizational cynicism (R2 = 0.57). Moreover, distributive injustice, negative workplace gossip, and organizational cynicism explained 75% of the variance in work disengagement (R2 = 0.72).

Finally, indirect impact was examined to evaluate the role of negative workplace gossip and organizational cynicism as mediators (see Table 5). For negative workplace gossip, the “bootstrapping analysis” determined that the indirect effect’s Std. β = 0.267 (0.620 × 0.430) was significant, with a t-value of 9.874. Furthermore, the indirect effect of 0.267, “95% Bootstrapped Confidence Interval” (LL = 0.214, UL = 0.320), does not straddle a zero in between, confirming mediation. As a result, the mediation effect of negative workplace gossip in the relationship between distributive injustice and work disengagement may be included as statistically significant. As a result, H4 is supported.

Moreover, according to Table 5, for organizational cynicism, the “bootstrapping analysis” determined that the indirect effect’s Std. β = 0.273 (0.780 × 0.350) was significant, with a t-value of 10.500. Furthermore, the indirect effect of 0.267, “95% Bootstrapped Confidence Interval” (LL = 0.222, UL = 0.324), does not straddle a zero in between, confirming mediation. As a result, the mediation effect of organizational cynicism in the relationship between distributive injustice and work disengagement may be included as statistically significant. As a result, H7 is supported.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore how work disengagement (WD) is affected by employees’ perceptions of distributive injustice (DI), taking into account workplace negative gossip (WNG) and organizational cynicism (OC) as mediators. The findings support our first hypothesis that there is a positive relationship between distributive injustice and work disengagement. This finding is consistent with those of earlier research by Aslam et al. [6], Rehman et al. [72], and [74], who claimed that job insecurity increases work disengagement. Work disengagement might be exacerbated by the negative emotional emotions induced by distributive injustice [74]. Employees who believe they have been treated unfairly may experience unpleasant emotions such as anger, resentment, frustration, or a sense of being devalued. These negative feelings can limit their ability to actively engage in their work, resulting in less effort or enthusiasm [19].

The findings also support our second hypothesis that there is a positive relationship between distributive injustice and workplace negative gossip. This finding is consistent with those of earlier research, e.g., Khan et al. [58], Kim et al. [80], and Noriko [81], who claimed that job insecurity increases workplace negative gossip. To damage the reputation or credibility of those they believe to be accountable for the injustice, employees may spread unfavorable information or rumors about the company or its executives. Negative gossip, in this way, acts as an attempt to reestablish a sense of justice by holding the accused wrongdoers responsible [127]. Moreover, employees’ social comparison processes are sparked by distributive injustice [83]. When people see inequity in the distribution of rewards, they participate in social comparisons, comparing their outcomes to those of others [84]. Negative gossip might serve as a sort of solidarity among employees who see themselves as victims of distributive injustice.

In addition, the findings support our third hypothesis that there is a positive relationship between workplace negative gossip and work disengagement. This finding is consistent with those of earlier research (e.g., Aboramadan et al. [88], Beersma et al. [89], and Li et al. [86], who claimed that workplace negative gossip increases work disengagement). Negative gossip corrodes trust between employees and undermines the establishment of psychological safety in the workplace. When employees participate in gossip, it fosters an environment of doubt and erodes the trust necessary for productive collaboration and engagement. As trust diminishes, employees may become more cautious, less inclined to take risks, and more prone to disengagement from their work [128,129].

Furthermore, the findings support our fourth hypothesis that workplace negative gossip mediates the link between distributive injustice and work disengagement. This finding is consistent with those of earlier research, e.g., Grosser et al. [34], Noriko [81], and Jiang et al. [82]. Negative gossip allows employees to communicate their thoughts of unfairness, debate instances of inequality, and vent their feelings. It turns into a coping strategy for staff members to handle the unfavorable emotions brought on by distributive injustice. Negative workplace gossip fosters the bad feelings associated with distributive injustice. Employees who engage in gossip and trade bad reports perpetuate a negative sequence, exacerbating the unpleasant feelings they are experiencing. Continuous exposure to bad talk might worsen sentiments of unhappiness, rage, and disengagement among employees.

Moreover, the findings support our fifth hypothesis that there is a positive relationship between distributive injustice and organizational cynicism. This finding is consistent with those of earlier research, e.g., Evans et al. [98] and Van Hootegem et al. [97], who claimed that distributive injustice increases organizational cynicism. Injustice judgments about reward distribution cause psychological discomfort for employees [130]. Individuals working in an organization suffer resource loss as a result of distributive unfairness and experience emotional aggression and bad emotions. To save resources, people attempt to mitigate distributive injustice. As a result, individuals respond to organizational policies, lack of integrity, and consistency, all of which are essential components of organizational cynicism [131].

Additionally, the findings support our sixth hypothesis that there is a positive relationship between organizational cynicism and work disengagement. This finding is consistent with earlier research by Chowdhury and Fernando [132], who claimed that organizational cynicism increases work disengagement. Cynics think that human activity is motivated by self-interest [133]. According to Detert et al. [134], cynicism is associated with unethical decision-making and less citizenship in organizations. Cynicism is also characterized by a lack of trust, and past studies have shown that people who do not trust others are less likely to be ethical themselves [133]. Cynics are reluctant to participate in or support initiatives that benefit others because they have a strong mistrust and contempt for other people [132].

Finally, the findings support our seventh hypothesis that organizational cynicism mediates the link between distributive injustice and work disengagement. This finding is consistent with those of earlier research by Ogunfowora et al. [117] and Van Hootegem et al. [97]. The perception of distributive injustice erodes confidence and promotes cynicism about the fairness and goals of the organization. Employees may become less motivated to commit their time, effort, and energy to their tasks when their trust has been damaged [17,115]. In addition, employees’ feelings of unfairness, including anger, resentment, and disillusionment, are prompted by distributive injustice. When employees see distributive injustice, they may feel deceived or unfairly treated, which increases their distrust of the organization. Emotional responses to distributive injustice lead to the establishment and reinforcement of organizational cynicism, which influences work disengagement [117].

6. Conclusions and Implications

The purpose of this study was to investigate how employees’ perceptions of distributive injustice (DI) affect work disengagement (WD). It also looked at the roles of workplace negative gossip (WNG) and organizational cynicism (OC) as mediators. The findings demonstrated a positive association between employees’ perceptions of distributive injustice and their level of work disengagement, as well as positive relationships between perceptions of distributive injustice and workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism. Positive associations were also found between workplace negative gossip, organizational cynicism, and work disengagement. Furthermore, the findings revealed that negative workplace gossip and organizational cynicism mediate the association between distributive injustice and work disengagement.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

Although tourism and hospitality workers are at significant risk of being exploited by organizations [135,136], studies that have empirically investigated the role of distributive injustice, cynicism, and negative gossip perceptions in the tourism and hospitality industry in the Egyptian context seem to be absent. Thus, we extend the literature with further evidence for the detrimental influence of these factors in the tourism and hotel context and identify their effects on tourism and hospitality employees’ work disengagement, which is a widespread and costly problem in hotels. In addition, examining the mediating effects of workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism between distributive injustice and work disengagement in the tourism and hospitality industries provides valuable insights into Social Exchange Theory. Social Exchange Theory posits that individuals participate in social interactions with the anticipation of reciprocal exchanges and resource sharing. By exploring the roles of workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism as mediators in the relationship between distributive injustice and work disengagement, this study enhances our comprehension of social exchange dynamics within the tourism and hospitality industries. It sheds light on the intricate interplay between social exchanges, negative perceptions, and employee outcomes.

Furthermore, this study makes a valuable contribution by identifying workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism as mediating mechanisms within the social exchange process. It investigates how these factors operate between distributive injustice and work disengagement, providing insights into the psychological processes that connect perceived unfairness to employee disengagement. This enhanced understanding deepens our knowledge of the underlying mechanisms through which social exchange processes unfold in the context of distributive injustice.

Additionally, the study underscores the significance of negative perceptions, including workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism, as crucial mediators in the connection between distributive injustice and work disengagement. It acknowledges that negative perceptions stemming from unfair treatment can have harmful consequences for employee engagement and motivation. This expansion of Social Exchange Theory emphasizes the importance of incorporating negative perceptions and their impact on employee outcomes within the framework of social exchange.

Moreover, the study’s specific focus on the tourism and hospitality industry offers industry-specific perspectives on the interplay between social exchange, distributive injustice, negative gossip, organizational cynicism, and work disengagement. This industry-specific understanding enhances the applicability and relevance of Social Exchange Theory by considering the unique challenges and characteristics of the tourism and hospitality sectors.

6.2. Practical Implications

The study’s findings have significant practical implications for the tourism and hospitality industries. In the competitive, dynamic, and labor-intensive industry of tourism and hospitality, managers must be aware of factors that might potentially reduce organizational performance. This study presents managers with empirical evidence that distributive injustice, cynicism, and negative gossip perceptions are threats to organizational performance in terms of job disengagement. One key implication is the importance of recognizing and addressing distributive injustice within organizations. Organizations in this industry must prioritize fairness and equity in the distribution of resources, including salaries, rewards, and opportunities for advancement. Implementing transparent and objective decision-making processes can help mitigate perceptions of unfairness and minimize the negative effects on employee engagement. Additionally, it is crucial to cultivate a positive organizational climate that discourages negative gossip and promotes trust and open communication. Organizations should strive to create a culture characterized by respect, collaboration, and fairness, which can help reduce the occurrence of negative gossip. Establishing transparent channels for employees to express their concerns and providing effective mechanisms for conflict resolution can contribute to a more positive work environment.

Tourism and hospitality organizations should take proactive measures to address and mitigate organizational cynicism. They can do so by promoting transparent communication, consistently demonstrating ethical behavior, and aligning organizational values with the interests of employees. Building trust and fostering a shared sense of purpose can effectively reduce organizational cynicism and cultivate higher levels of employee engagement.

Furthermore, these organizations need to allocate resources toward initiatives that enhance employee engagement, job satisfaction, and a sense of purpose. This can involve offering opportunities for skill development, acknowledging and rewarding employee contributions, and cultivating a supportive and inclusive workplace environment. Engaging employees in this manner increases their motivation, commitment, and productivity, ultimately resulting in improved organizational performance.

In addition, tourism and hospitality organizations can offer training and educational programs that emphasize the significance of fairness, equity, and effective communication. These programs can help employees comprehend the consequences of distributive injustice, negative gossip, and organizational cynicism on work disengagement. By providing employees with the skills to navigate challenging situations, handle conflicts, and foster a positive work culture, organizations can contribute to a healthier and more engaged workforce.

Managers need to give priority to establishing a culture of fairness and transparency in all facets of resource allocation, such as salaries, benefits, assignments, and promotions. They should effectively communicate the criteria and procedures used in decision-making to ensure that employees perceive distributive justice. By doing so, the likelihood of negative gossip and organizational cynicism stemming from perceived unfairness can be reduced.

Moreover, managers should foster a positive work climate that discourages negative gossip while promoting open communication and collaboration. This can be achieved by encouraging managers and leaders to be accessible and responsive to employee concerns. Providing opportunities for team-building activities and implementing initiatives that foster a sense of camaraderie and shared purpose can also contribute to a positive work climate. By cultivating such an environment, the development of negative gossip and organizational cynicism can be mitigated, resulting in higher levels of employee engagement.

Finally, managers need to promote a culture of constructive feedback and open dialogue throughout the organization. They should encourage employees to provide feedback regarding perceived distributive injustice and create platforms for open discussions. This approach helps address concerns, rectify misconceptions, and prevent the propagation of negative gossip. Actively involving employees in discussions about distributive justice fosters a more engaged and empowered workforce.

7. Limitations and Future Research

Although the study examining the mediating roles of workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism between distributive injustice and work disengagement in the tourism and hospitality industries offers valuable insights, it is essential to recognize its limitations and identify potential avenues for future research. The primary limitation is the study’s narrow focus on the tourism and hospitality industries, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other industries. Future research could investigate whether similar mediating roles exist in diverse sectors or industries, such as airlines, to ascertain the broader applicability of the study’s findings.

A second limitation to consider is the extent to which the study’s findings depend on the accuracy and reliability of the measurement tools utilized. To enhance the depth of future research, it would be valuable to incorporate multiple measurement methods, such as self-report surveys, observation, and qualitative interviews. This approach would contribute to a more comprehensive comprehension of the constructs being examined and further enrich our understanding of the subject matter.

Similarly, it is worth noting that although the study identified workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism as mediators, there is room for further investigation into the underlying mechanisms through which these variables mediate the relationship between distributive injustice and work disengagement. It would be beneficial for future research to delve deeper into these mechanisms. This could involve exploring additional variables, such as perceived organizational support, trust, or job satisfaction, which could contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the mediating processes involved.

Additionally, it is important to consider that the study’s findings may be influenced by cultural and contextual factors that are specific to the tourism and hospitality industries. Future research could investigate how cultural differences and varying organizational contexts impact the relationships between distributive injustice, negative gossip, organizational cynicism, and work disengagement. By comparing findings across different cultural and contextual settings, valuable insights can be gained regarding the generalizability and boundary conditions of the study’s findings.

Furthermore, it is important to note that while the study identified the mediating roles of workplace negative gossip and organizational cynicism, future research could focus on exploring effective intervention strategies to mitigate the negative effects of distributive injustice and its mediators on work engagement. Investigating interventions such as leadership training, organizational policies, or employee support programs could offer practical guidance for organizations aiming to effectively address these issues. By identifying and implementing appropriate interventions, organizations can create a more positive and engaging work environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F.A., H.A.K., B.S.A.-R. and M.A.A.F.; methodology, H.A.K., R.M.A. and M.F.A.; software, M.F.A., N.A., H.A.K., Y.H.M., J.A. and B.S.A.-R.; validation, H.A.K., N.A., M.F.A., J.A. and R.M.A.; formal analysis, R.M.A., M.F.A., M.A.A.F. and B.S.A.-R.; investigation, J.A., N.A., M.F.A., Y.H.M. and B.S.A.-R.; resources, M.F.A. and N.A.; data curation, H.A.K., M.F.A. and J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F.A., H.A.K., N.A. and B.S.A.-R.; writing—review and editing, M.F.A., H.A.K., B.S.A.-R., M.A.A.F., R.M.A. and Y.H.M.; visualization, H.A.K., N.A., M.F.A., R.M.A. and B.S.A.-R.; supervision, H.A.K., M.F.A. and B.S.A.-R.; project administration, H.A.K., N.A., M.F.A., Y.H.M., M.A.A.F. and R.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Project No. GRANT 4244].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request from researchers who meet the eligibility criteria. Kindly contact the first author privately through email.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Distributive injustice Colquitt [118] |

| DI.1. In a hotel/travel agency, the outcome process does not reflect the effort I have put into my work. |

| DI.2. In a hotel/travel agency, the outcome process is inappropriate for the work I completed. |

| DI.3. In a hotel/travel agency, the outcome process does not reflect what I have contributed to the organization. |

| DI.4. In a hotel/travel agency, the outcome process is unjustified, given my performance. |

| Negative workplace gossip Brady et al. [120] |

| NWG.1. I asked a work colleague if they had a negative impression of something that your supervisor had done. |

| NWG.2. I questioned your supervisor’s abilities while talking to a work colleague. |

| NWG.2. I criticized your supervisor while talking to a work colleague. |

| NWG.4. I vented to a work colleague about something that your supervisor has done. |

| NWG.5. I told an unflattering story about your supervisor while talking to a work colleague. |

| NWG.6. I asked a work colleague if they had a negative impression of something that another co-worker had done. |

| NWG.7. I questioned a co-worker’s abilities while talking to another work colleague. |

| NWG.8. I criticized a co-worker while talking to another work colleague. |

| NWG.9. I vented to a work colleague about something that another co-worker had done. |

| NWG.10. I told an unflattering story about a co-worker while talking to another work colleague. |

| Work disengagement Schaufeli [119] |

| WD.1. At my work, I do not feel bursting with energy. |

| WD.2. At my work, I do not feel strong and vigorous. |

| WD.3. I am not enthusiastic about my work. |

| WD.4. My work does not inspire me. |

| WD.5. When I get up in the morning, I do not feel like going to work. |

| WD.6. I do not feel happy when I am working intensely. |

| WD.7. I am not proud of the work that I do. |

| WD.8. I am not immersed in my work. |

| WD.9. I do not get carried away when I am working. |

| Organizational Cynicism Wilkerson et al. [121] |

| OC.1. Any efforts to make things better around here are likely to succeed. [R] |

| OC.2. The hotel/travel agency’s management is good at running improvement programs or changing things in our business. [R] |

| OC.3. Overall, I expect more success than disappointment in working with this hotel/travel agency. [R] |

| OC.4. My hotel/travel agency pulls its fair share of the weight in its relationship with its employees. [R] |

| OC.5. Suggestions on how to solve problems around here will not produce much real change. |

| OC.6. My hotel/travel agency meets my expectations for the quality of my work life. [R] |

| OC.7. The hotel/travel agency’s management is more interested in its goals and needs than in its employees’ welfare. |

Appendix B. Model Fit and Quality Indices

| Assessment | Criterion | Supported/Rejected | |

| Average path coefficient (APC) | 0.462, p < 0.001 | p < 0.05 | Supported |

| Average R-squared (ARS) | 0.557, p < 0.001 | p < 0.05 | Supported |

| Average adjusted R-squared (AARS) | 0.556, p < 0.001 | p < 0.05 | Supported |

| Average block VIF (AVIF) | 2.397 | acceptable if ≤5, ideally ≤3.3 | Supported |

| Average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF) | 2.281 | acceptable if ≤ 5, ideally ≤3.3 | Supported |

| Tenenhaus GoF (GoF) | 0.588 | small ≥ 0.1, medium ≥ 0.25, large ≥ 0.36 | Supported |

| Sympson’s paradox ratio (SPR) | 1.000 | acceptable if ≥0.7, ideally = 1 | Supported |

| R-squared contribution ratio (RSCR) | 1.000 | acceptable if ≥0.9, ideally = 1 | Supported |

| Statistical suppression ratio (SSR) | 1.000 | acceptable if ≥0.7 | Supported |

| Nonlinear bivariate causality direction ratio (NLBCDR) | 1.000 | acceptable if ≥0.7 | Supported |

References

- Fuller, L.P. Distributive Injustice: Leadership Adherence to Social Norm Pressures and the Negative Impact on Organizational Commitment. Int. Bus. Res. 2021, 14, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, K.E.; O’Leary-Kelly, A.M. Unraveling the Psychological Contract Breach and Violation Relationship: Better Evidence for Why Broken Promises Matter. J. Manag. Issues 2021, 33, 140–156. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J.S. Towards an Understanding of Inequity. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1963, 67, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restubog, S.L.D.; Deen, C.M.; Decoste, A.; He, Y. From Vocational Scholars to Social Justice Advocates: Challenges and Opportunities for Vocational Psychology Research on the Vulnerable Workforce. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 126, 103561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hystad, S.W.; Mearns, K.J.; Eid, J. Moral Disengagement as a Mechanism between Perceptions of Organisational Injustice and Deviant Work Behaviours. Saf. Sci. 2014, 68, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, U.; Muqadas, F.; Imran, M.K.; Rahman, U.U. Investigating the Antecedents of Work Disengagement in the Workplace. J. Manag. Dev. 2018, 37, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, A. The Relationships of Organizational Injustice with Employee Burnout and Counterproductive Work Behaviors: Equity Sensitivity as a Moderator. 2006. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/d06b415c05648f7d1b795e475a018538/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Butt, S.; Yazdani, N. Influence of Workplace Incivility on Counterproductive Work Behavior: Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion, Organizational Cynicism and the Moderating Role of Psychological Capita. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2021, 15, 378–404. [Google Scholar]

- Dar, N.; Khan, S.; Rauf, A. Deviant Behavior and Organizational Justice: Mediator Test for Organizational Cynicism—The Case of Pakistan. Asian J. Econ. Financ. 2020, 2, 333–347. [Google Scholar]

- Soltis, S.M.; Agneessens, F.; Sasovova, Z.; Labianca, G. A Social Network Perspective on Turnover Intentions: The Role of Distributive Justice and Social Support. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 52, 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadirov, O.; Dehning, B. Trust in Public Programmes and Distributive (in)Justice in Taxation. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2023, 36, 2222307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Guo, S. The Impact of Negative Workplace Gossip on Employees’ Organizational Self-Esteem in a Differential Atmosphere. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 854520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R.S.; Dierdorff, E.C.; Bommer, W.H.; Baldwin, T.T. Do Leaders Reap What They Sow? Leader and Employee Outcomes of Leader Organizational Cynicism about Change. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, U.; Ilyas, M.; Imran, M.K.; Rahman, U.U. Detrimental Effects of Cynicism on Organizational Change: An Interactive Model of Organizational Cynicism (a Study of Employees in Public Sector Organizations). J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2016, 29, 580–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.S.; Burchell, M.J. Make Work Healthy: Create a Sustainable Organization with High-Performing Employees; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, G.; Cheng, B.; Tian, J.; Ma, J.; Gong, C. Effects of Negative Workplace Gossip on Unethical Work Behavior in the Hospitality Industry: The Roles of Moral Disengagement and Self-Construal. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2021, 31, 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, R. Organizational Cynicism: Bases and Consequences. Genet. Soc. Gen. 2000, 126, 269. [Google Scholar]

- Abugre, J.B. Relations at Workplace, Cynicism and Intention to Leave: A Proposed Conceptual Framework for Organisations. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2017, 25, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.; Zhang, L. Perceived Overall Injustice and Organizational Deviance—Mediating Effect of Anger and Moderating Effect of Moral Disengagement. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1023724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapouraghdam, H.; Alipour, H.; Arasli, H. Workplace Spirituality and Organization Sustainability: A Theoretical Perspective on Hospitality Employees’ Sustainable Behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 21, 1583–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairy, H.A.; Agina, M.F.; Aliane, N.; Hashad, M.E. Internal Branding in Hotels: Interaction Effects of Employee Engagement, Workplace Friendship, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, O.; Dogru, T.; Kizildag, M.; Erkmen, E. A Critical Reflection on Digitalization for the Hospitality and Tourism Industry: Value Implications for Stakeholders. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 3305–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, M.N.; Zolin, R.; Muhammad, N. The Combined Effect of Perceived Organizational Injustice and Perceived Politics on Deviant Behaviors. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2021, 32, 62–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, M.S. Organizational Change and Employee Stress. Manag. Sci. 2011, 57, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marescaux, E.; De Winne, S.; Sels, L. Idiosyncratic Deals from a Distributive Justice Perspective: Examining Co-Workers’ Voice Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Tabatabaei, F.; Khoshkam, M.; Shahabi Sorman Abadi, R. Exploring the Role of Perceived Organizational Justice and Organizational Commitment as Predictors of Job Satisfaction among Employees in the Hospitality Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2021, 24, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, M.R. Organizational Cynicism: Its Relationship to Perceived Organizational Injustice and Explanatory Style—ProQuest. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10911359.2017.1421111 (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Naeem, M.; Weng, Q.; Ali, A.; Hameed, Z. An Eye for an Eye: Does Subordinates’ Negative Workplace Gossip Lead to Supervisor Abuse? Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pheko, M.M. Rumors and Gossip as Tools of Social Undermining and Social Dominance in Workplace Bullying and Mobbing Practices: A Closer Look at Perceived Perpetrator Motives. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2018, 28, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özlük, B.; Özcan, Ö. One of the Informal Communication Channels among Nurses: Attitudes and Thoughts Toward Gossip and Rumors. J. Educ. Res. Nurs. 2021, 18, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Schilpzand, P.; Liu, Y. Workplace Gossip: An Integrative Review of Its Antecedents, Functions, and Consequences. J. Organ. Behav. 2023, 44, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellwardt, L.; Labianca, G.J.; Wittek, R. Who Are the Objects of Positive and Negative Gossip at Work?: A Social Network Perspective on Workplace Gossip. Soc. Netw. 2012, 34, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şantaş, G.; Uğurluoğlu, Ö.; Özer, Ö.; Demir, A. Do Gossip Functions Effect on Organizational Revenge and Job Stress Among Health Personnel? J. Health Manag. 2018, 20, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosser, T.J.; Lopez-Kidwell, V.; Labianca, G.L.; Ellwardt, L. Hearing It through the Grapevine. Positive and Negative Workplace Gossip. Organ. Dyn. 2012, 41, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Balliet, D.; Van Lange, P.A.M. Reputation, Gossip, and Human Cooperation. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2016, 10, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.I.; Iftikhar, M.; Janjua, S.Y.; Zaman, K.; Raja, U.M.; Javed, Y. Empirical Investigation of Mobbing, Stress and Employees’ Behavior at Work Place: Quantitatively Refining a Qualitative Model. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar, O.; Karcıoğlu, F.; Aslan, İ. The Relationships among Organizational Cynicism, Job Insecurity and Turnover Intention: A Survey Study in Erzurum/Turkey. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 150, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinheider, B.; Verdorfer, A.P. Climate Change? Exploring the Role of Organisational Climate for Psychological Ownership. In Theoretical Orientations and Practical Applications of Psychological Ownership; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 275–293. [Google Scholar]

- Noh, G.; Kim, S.; Jung, K.; Kang, L.K. What Makes Employees Cynical in Public Organizations? Antecedents of Organizational Cynicism. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2019, 47, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.C.; Chang, K.; Quinton, S.; Lu, C.Y.; Lee, I. Gossip in the Workplace and the Implications for HR Management: A Study of Gossip and Its Relationship to Employee Cynicism. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 26, 2288–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakari, H.; Hunjra, A.I.; Jaros, S.; Khoso, I. Moderating Role of Cynicism about Organizational Change between Authentic Leadership and Commitment to Change in Pakistani Public Sector Hospitals. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2019, 32, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agina, M.; Abdelhakim, H. The Impact of Organizational Politics on Employee Turnover Intentions in Hotels and Travel Agencies in Egypt. J. Assoc. Arab. Univ. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 20, 178–197. [Google Scholar]

- Heikkeri, E. Roots and Consequences of the Employee Disengagement Phenomenon; Saimaa University of Applied Sciences: Lappeenranta, Finland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pishghadam, R.; Ebrahimi, S.; Golzar, J.; Miri, M.A. Introducing Emo-Educational Divorce and Examining Its Relationship with Teaching Burnout, Teaching Motivation, and Teacher Success. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 29198–29214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fida, R.; Paciello, M.; Tramontano, C.; Fontaine, R.G.; Barbaranelli, C.; Farnese, M.L. An Integrative Approach to Understanding Counterproductive Work Behavior: The Roles of Stressors, Negative Emotions, and Moral Disengagement. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z. Employee Disengagement: A Fatal Consequence to Organization and Its Ameliorative Measures. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2017, 7, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.H.; Wellman, N.; Ashford, S.J.; Lee, C.; Wang, L. Deviance and Exit: The Organizational Costs of Job Insecurity and Moral Disengagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, E.D. Beginning’s End: How Founders Psychologically Disengage from Their Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 59, 1605–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.S.; Cropanzano, R.S.; Quisenberry, D.M. Social exchange theory, exchange resources, and interpersonal relationships: A modest resolution of theoretical difficulties. In Handbook of Social Resource Theory: Theoretical Extensions, Empirical Insights, and Social Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Sears, G.; Zhang, H. Revisiting the “Give and Take” in LMX: Exploring Equity Sensitivity as a Moderator of the Influence of LMX on Affiliative and Change-Oriented OCB. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 555–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, K.W.; Ravichandran, T. Exploring the Determinants of Knowledge Exchange in Virtual Communities. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2015, 62, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agina, M.; Mohammed, M.A.; Omar, A. Role of Leader-Member Exchange and Impression Management in Employee Performance at Hotels. J. Fac. Tour. Hotel.-Univ. Sadat City 2017, 1. [Google Scholar]