1. Introduction

Oil and gas remain pivotal in global energy markets, significantly affecting economic growth and human development. However, they are also fraught with geopolitical complexities [

1], as seen in the escalating tensions between Europe and Russia [

2]. While investment in these sectors burgeons, reaching an unprecedented USD 2.4 trillion in 2022 [

3], the critical issue of sustainability looms large. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Index evaluated the current standing and advancement of 193 UN member states, ranking Finland, Sweden, and Denmark, as the top performers. Although there has been incremental improvement in various indicators, the current rate of advancement is insufficient to meet any of the 2030 targets [

4].

As in past years, the pace of progress is notably uneven across regions, with certain areas making substantial strides while others either stall or regress. It is important to note that, in international policy, global growth has prompted numerous countries to alter their consumption behaviors, which in turn affects their energy consumption and mixes. While this is a step forward, not all developing nations, for instance Bangladesh and Nigeria, have succeeded in matching high growth rates with substantial renewable energy rates. Despite this, several of these nations have pivoted their industrial frameworks to adopt more sustainable, environmentally friendly models. A case in point is China’s transition to a circular economy, which serves as an instructive example in this context [

5].

The primary aim of this study is to conduct a comparative analysis of the legal frameworks governing the oil and gas sectors in Bangladesh and Nigeria, with a focus on their effectiveness in achieving SDG 7. The vital importance of energy in facilitating the attainment of the SDGs has been recognized widely [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Nigeria is a leading oil and gas producer in Africa, holding the continent’s largest proven gas reserves and ranking ninth globally. As a key Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) member, its economy heavily depends on its oil sector, which boasts around 37 billion barrels of reserves. While Nigeria is a dominant player in Africa’s oil and gas sector, Bangladesh is an emerging force in South Asia, focusing more on natural gas than oil. With proven gas reserves estimated at over 14 trillion cubic feet, Bangladesh relies heavily on its natural gas industry to fuel its developing economy.

In the context of achieving energy sustainability, analyzing two economically divergent nations with varying levels of national resource endowments, i.e., Bangladesh and Nigeria, allows for a critical assessment of policy success and stakeholder engagement in a diverse context. Bangladesh, constrained by its limited resources, and Nigeria, endowed with substantial oil and gas reserves, each bring to the table distinctive approaches and strategies shaped by their individual historical and geopolitical landscapes. A thorough investigation of their current legal frameworks and policies can illuminate the efficacy of their respective strategies, while also identifying best practices and pinpointing areas where stakeholder engagement can be enhanced or is already proving successful. The choice of Bangladesh and Nigeria for such a study is motivated by the potential for deep insights into how different economic and geopolitical backgrounds influence the crafting and implementation of legal frameworks governing the energy sector. Therefore, the focus of this comparative study is twofold: to assess the current legal instruments’ ability to facilitate sustainable energy practices and to highlight any deficiencies or inconsistencies that may need redress. This research will serve as a comprehensive resource for policymakers, regulators, and academicians, offering valuable insights for the better planning, execution, and amendment of existing regulatory frameworks aligned with SDG 7. Further, the study will serve to create a pathway for informed policy reforms, pinpointing opportunities for bilateral collaboration and knowledge transfer, aiming to expedite the realization of SDG 7 through a cooperative, mutually beneficial approach.

1.1. Literature Review

To guarantee enduring social and economic wellbeing, energy will persist as a key player across several domains, whether it be in propelling growth, spearheading climate mitigation initiatives, or promoting sustainable development. This is because energy is intricately intertwined with all the other 16 SDGs, and its significance, particularly in driving economic progress, has been firmly established [

10,

11,

12]. Due to the growing importance of energy in promoting economic development, it has been incorporated into the production function and serves as a fundamental factor in explaining the sources of economic growth [

13,

14,

15].

Numerous studies highlight the energy sector’s negative externalities [

16,

17,

18], prompting a shift towards sustainable development (SD) [

19] and making the term “sustainable energy development” (SED) increasingly prevalent in academic writings [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. As mentioned earlier, SDG 7 targets providing everyone with access to affordable, dependable, sustainable, and contemporary energy by 2030. In order to achieve SDG 7, it is imperative to increase the use of alternative, including renewable, energy sources in the energy mix [

28,

29,

30], enhance the energy efficiency [

31,

32], and reduce greenhouse gas emissions and air pollutants [

33,

34,

35].

The transition from traditional fossil fuel-based energy systems to clean and renewable energy sources is a complex task that requires international cooperation and the involvement of various stakeholders [

36,

37]. To address this challenge, countries like Taiwan and Japan have implemented electricity sector reforms and used legal tools to promote fair competition and stable electricity supply, aligning with the principles of energy justice and the SDGs [

38]. Several studies have delved into the utilization of solar and wind energy [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Similarly, a substantial corpus of literature addresses biomass consumption, as evidenced from the work of several authors [

44,

45,

46]. Biogas usage has been the subject of investigations by researchers and found to be a viable alternative to traditional energy [

44,

47,

48]. Moreover, innovative methodologies in harnessing renewable energy through hydropower have been showcased in several studies [

49,

50,

51].

As global dialogues on global warming and climate change intensify, energy efficiency is increasingly recognized as a pivotal element of sustainable development, prompting governments worldwide to incorporate it into their strategic planning [

52,

53,

54]. Energy efficiency also plays a vital role in enhancing energy security and improving business competitiveness and the wellbeing of citizens [

55,

56]. Over time, as political and economic priorities have shifted, governments have emphasized different justifications for continuing to develop policies on energy efficiency. These justifications include enhancing energy security, improving affordability, boosting business competitiveness, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions as mandated by SDG 7 [

55]. The International Energy Agency, in its report, identified multifaceted benefits of energy efficiency, from reducing dependency on primary energy uses to the price, amount, and cost of energy imports [

57,

58]. Developing countries like Bangladesh and Nigeria heavily rely on importing gas and oil to meet local demand. Therefore, they need an adequate policy framework to achieve sustainability goals and balance the supply and demand equation to achieve the desired economic growth while improving energy security, enhancing competitiveness, and advancing environmental sustainability.

Measurement frameworks for energy access should consider both energy supply conditions and the status of household energy poverty to effectively target policies and accelerate the provision of affordable and reliable energy services [

38]. In Africa, strategic energy planning is crucial to achieving universal electricity access and meeting future energy needs. Increasing the penetration of renewable energy sources can create jobs, increase cost efficiency, and contribute to a less carbon-intensive power system [

59]. There is a prevailing discussion among scientists concerning energy poverty and the transition to low-carbon energy. This debate suggests that climate change mitigation policies applied in the energy sector and associated areas may not necessarily promote economic growth, social development, or alleviate energy poverty [

60,

61,

62,

63]. As a result, some argue that climate initiatives lack a systematic approach and that the expenses associated with these actions are disproportionately high compared to the ability to shoulder such costs [

64,

65,

66]. Lazarou et al. and Kang et al. (2020) advocate for a mix of optimal technology portfolios and financial and political incentives to spur technological innovation [

67,

68]. However, Kalina contended that our future’s trajectory hinges not merely on technology but necessitates a comprehensive approach, calling for cohesive multi-disciplinary and interdisciplinary actions [

69]. Early climate mitigation investments are vital for middle-income countries, facing numerous challenges, as highlighted by other authors [

62,

70]. Emphasizing innovation and economic diversification, some authors consider them as essential for advancing climate mitigation and promoting renewables in energy markets [

71,

72]. Sovacool et al. [

73] and Heffron and McCauley [

74] contended that well-defined energy justice principles are crucial for empowering policymakers and planners to design equitable systems that safeguard the most at-risk individuals both presently and in the years ahead.

National governments are employing diverse policy tools to bolster clean energy technologies, facilitating the shift away from fossil fuels to support energy sustainability in Bangladesh and Nigeria. The majority of the literature focuses on either developed countries or an entire continent rather than analyzing specific countries like Bangladesh and Nigeria. Some of the literature gives attention to these specific countries but they lack the analytical effectiveness of the present regulatory framework in relation to rectifying system inefficiencies, market failures, and innovation bottlenecks hindering the spread of clean energy technologies to achieve SDG 7.

1.2. Context and Background

SDG 7, which focuses on eliminating energy poverty, sets two pivotal targets: guaranteeing universal electricity access and providing everyone with clean cooking technologies and fuels by the year 2030. From 2000 to 2016, the population lacking electricity access decreased from 1.7 billion to approximately 1 billion. Currently, about a billion people are without electricity access, limiting their developmental potential. Despite progress in certain SDG 7 indicators, 40% of global households, or 3 billion individuals, still rely on traditional cooking methods daily. Given current trends and policies, it is estimated that, by 2030, 670 million will remain without electricity, and approximately 2.3 billion will lack clean cooking facilities [

4].

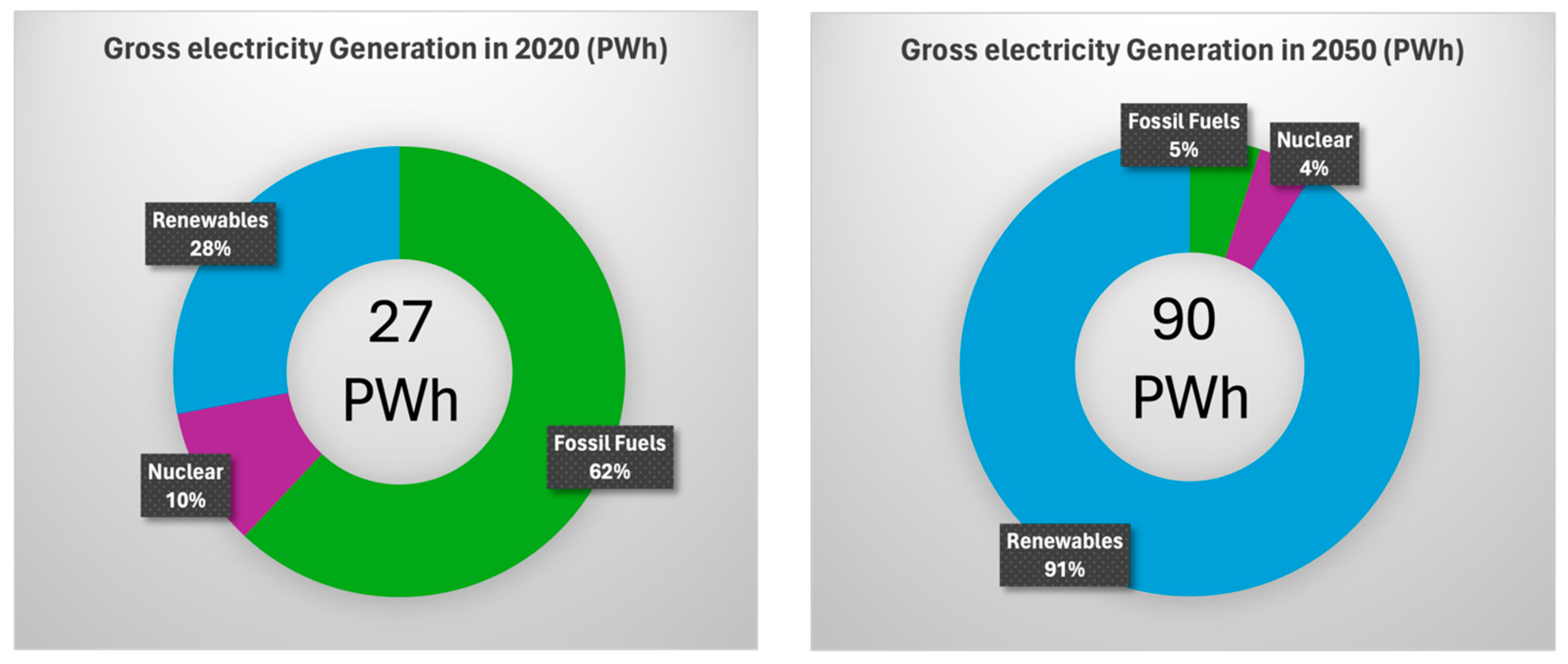

To meet the Paris Agreement’s aim of limiting temperature rises to 1.5 °C, the energy sector, responsible for two thirds of global GHG emissions, must rapidly transition from fossil fuels to zero-carbon sources by mid-century. To limit global warming to 1.5 °C, societies must transform energy consumption and production, aiming for net-zero energy sector emissions by 2050, a 6% decrease in energy use from 2020 levels, and a jump from 16% to 77% in renewable energy use by 2050 [

75]. Therefore, electricity generation will need to be tripled by 2050 from 2020 levels, with renewables accounting for 91%, up from 28% in 2020, to achieve 1.5 °C, as portrayed in

Figure 1.

While renewable energy sources are growing in power generation, their incorporation in end-use sectors like buildings, industries, and transportation remains limited. In 2015, the percentage of renewables in the total final consumption (TFEC) saw a slight increase to 17.5%, a rise from 16.7% in 2010 [

76]. In 2015, around 22.8% of global electricity production came from renewable sources, while fossil fuels and nuclear accounted for the remaining portion.

The present energy efficiency improvement rate, at 2.2% annually, falls short of the 2.7% yearly target required globally [

4]. Energy efficiency is gaining prominence in countries’ sustainable development strategies, with a rising number of nations adopting related targets and policies. Of the 189 countries with Indented Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs), 147 mentioned renewable energy and 167 cited energy efficiency. By 2016, 137 countries had energy efficiency policies, and 149 set targets, with 48 and 56 countries, respectively, introducing or updating these in 2015–2016 [

77]. Today, 31.5% of global energy use is mandated by efficiency policies, a 17% rise since 2005 [

78]. Further, in October 2016, a significant amendment to the Montreal Protocol aimed to reduce hydrofluorocarbons, harmful gases used in cooling systems. Philanthropic funds allocated USD 53 million to expedite developing countries’ transition to energy-efficient, eco-friendly cooling, amplifying the climate benefits.

1.2.1. The Present Energy Landscape in Nigeria

Nigeria is widely recognized for being among the nations with abundant oil and gas reserves. Specifically, Nigeria has a reputation as a significant producer of natural gas, boasting the highest amount of proven gas reserves on the African continent and ranking ninth globally. Nigeria, being an essential player in Africa’s oil production, greatly relies on its oil sector for its economy. It is part of OPEC and is considered one of the largest oil producers in Africa, with a reserve of around 37 billion barrels of oil as per OPEC data. Studies showed that the Nigerian economy is heavily dependent on the oil and gas industry, as around 5.8% of Nigeria’s real GDP in 2019 was contributed by the oil and gas industry, which also generated 95% of the country’s foreign exchange income and 80% of its budget revenue [

79,

80].

As of 2022, Nigeria boasts immense natural gas deposits with proven gas reserves of 208.62 trillion cubic feet (“tcf”)—a 1.01% increase from the previous year, alongside unproven gas reserves of 600 tcf, comprising both associated and non-associated gas, notwithstanding non-associated gas holding more of Nigeria’s gas reserves, associated gas accounts for 69.55% of the country’s total production [

81]. Despite this, Nigeria is still underutilizing its abundant gas reserves. The country’s oil reserves are 36.972 billion barrels, meaning the gas reserves are 900 times higher than its oil reserves [

82]. It will take nearly 50 and 75 years to fully exploit the country’s proven petroleum reserves [

83].

Figure 2 shows Nigeria’s total energy supply by source.

Although Nigeria has abundant petroleum and natural resources to meet the demand of the country, the country is still facing an acute energy crisis. The International Energy Agency states that around 140 million Nigerians, or 71% of the population, lack access to energy [

4]. Only 45% of Nigeria’s population is connected to the energy grid, with the majority residing in urban areas. In Nigeria, 55.4% of the population has access to electricity, while only 15% can access clean fuel [

76]. Over 80% of energy consumption comes from petroleum, leading to environmental concerns and resource depletion. Research from the Nigerian Power Sector recovery program shows that 80 percent of Nigerian business enterprises face electrification challenges resulting in USD 25 billion in annual economic losses [

85]. Fundamentally, the utilization of fossil fuel as a source of energy generation has not yielded favorable results over time in Nigeria, leading to severe repercussions on the advancement and prosperity of economies as about 55 percent of the total population is still lacking access to electricity in Nigeria and this number would be less than 30 in some rural areas [

86]. However, transitioning to low-carbon energy is challenged by poor management, funding constraints, misconceptions about costs, limited public awareness, ineffective strategies, lack of expertise, and a weak regulatory framework [

87]. The 2021 Global Status Report on renewables indicates that Nigeria’s renewable power capacity is under 2 gigawatts, and, excluding hydropower, it stands at approximately 0.01 gigawatts per person. Numerous factors, including political, technical, socio-cultural, financial, economic, market related, geographical, and ecological issues, hinder the adoption of renewable energy technologies. The absence of supportive policies, regulations, and clear legal procedures curtails RET development. Clear policies and regulatory measures, such as standards and codes, are crucial to attract investors and mitigate technological and regulatory risks [

88].

1.2.2. The Present Energy Landscape in Bangladesh

Bangladesh has been improving in all spheres of human endeavor, including the oil and gas sector, because the sector is considered an important sector for the economy and national development [

89]. The significance of the petroleum sector cannot be underestimated, as it is crucial for achieving the country’s aspirations of becoming the 24th-largest economy by 2030 and a developed nation by 2041. The effectiveness and efficiency of the oil and gas sector are critical for the successful attainment of these national development goals [

90,

91]. The sector is expected to enhance the country’s energy security and self-sufficiency significantly, contribute to its economic growth and development [

51], and ensure affordable energy for all citizens. Therefore, the government’s focus on developing and improving the oil and gas sector is crucial to its broader national development agenda.

Interestingly, oil specifically accounts for 16%, while natural gas accounts for 41%, equivalent to 54.60 million tons of oil—currently, the demand for petroleum products in the country is 73 million metric tons [

92]. According to the data available from 2016, Bangladesh has proven oil reserves of approximately 28 million barrels, which ranks the country at the 82nd position globally. These oil reserves account for only 0.0% of the world’s total oil reserves, which stood at more than 1.5 trillion barrels during the same period. Therefore, Bangladesh heavily relies on oil imports to sustain its current consumption levels. Furthermore, the total oil reserves in Bangladesh are insufficient even to meet the country’s annual oil consumption, estimated at 41,245,000 barrels in 2016 [

93]. Consequently, Bangladesh’s energy security is highly dependent on imported oil, which poses significant economic and geopolitical risks for the country [

93].

Figure 3 postulates the total energy supply by source of Bangladesh.

The government is implementing measures to introduce land-based liquefied natural gas (LNG) facilities to enhance efficiency in Bangladesh’s oil and gas sector. To achieve this goal, the government has awarded long-term contracts to different prominent LNG traders and suppliers for the execution of this project. Implementing this project is a significant step towards the country’s energy security and self-sufficiency.

The country is said to have a production capacity of 4105 barrels per day [

93]. Unfortunately, the government is still depending on refined petroleum imported from overseas. Literature contends that, in 2021, 8% of the country’s demand for fuel was fulfilled from domestic sources, and the remaining 92% was imported [

92]. According to the Statistics made available by Hydrocarbon Unit, Energy and Mineral Resources Division, it is reported that Bangladesh imports almost 1.3 million metric tons (MT) of crude oil and approximately 6.7 million metric tons (MT) of refined petroleum products per year.

In Bangladesh, like Nigeria, electricity production is heavily dependent on natural gas, oil, and coal—resources that are finite [

94]. However, Bangladesh boasts over 90% electricity accessibility for its population, outpacing Nigeria considerably in this aspect.

Figure 4 shows the present electricity access of both countries.

Both nations are among the 20 countries accounting for 80% of the world’s gap in access to clean cooking [

76]. As of 2020, a mere 25% of the Bangladeshi population had access to clean cooking, a stark contrast to the over 90% that had electricity access [

4]. In both Nigeria and Bangladesh, the urban population has greater access to clean cooking fuel compared to those in rural areas [

76].

Figure 5 shows the access to clean fuels and technologies for cooking among urban populations over the period.

Consequently, the predominant cause of energy poverty in Bangladesh and Nigeria stems from the lack of access to clean cooking fuels and technologies. It is projected that the world’s total fossil fuels will be completely depleted within a few decades [

95]. Additionally, these resources are becoming rapidly scarcer and more expensive. To guarantee energy security, many countries are increasingly turning to renewable energy sources to meet their electricity needs. From a geographical standpoint, Bangladesh holds a favorable position for expanding renewable energy production. Its geographic location provides several advantages conducive to thriving in sustainable renewable energy generation. However, In Bangladesh, renewable energy (RE) contributes a mere 3.24% to the national electricity production, whereas Nigeria’s renewable power capacity stands at less than 2 gigawatts [

96].

Figure 6 shows the percentage of renewable energy consumption of both countries.

Both Bangladesh and Nigeria are far behind achieving sustainable energy despite government efforts to sustainably align energy supply with the goals of SDG 7 through various policies and technologies. Further, both countries are increasingly gravitating towards sustainable energy sources such as solar, wind, bio-energy, hydropower, geothermal, and marine energy. This shift is motivated by the finite reserves of petroleum-based fuels and their detrimental environmental impacts. However, not only do existing and forthcoming policies in Bangladesh and Nigeria fall short of aligning with SDG 7, but the pace toward achieving certain milestones has also decelerated. One of the prime reasons for such deceleration is that existing policy and regulatory frameworks remain predominantly centered around fossil fuels, providing inadequate public funding to support the energy transition. Across all sectors and regions, a consistent factor is the establishment of appropriate framework conditions. It is imperative that public institutions collaborate effectively and efficiently with the broader society to realize sustainable development goals. Strengthened policy initiatives are crucial for integrating renewables, advancing electrification, and driving decarbonization, ensuring alignment with the goals of Net Zero Emissions by 2050 and the 1.5 °C climate targets.

2. Materials and Methods

The study adopts a doctrinal legal research approach, underscored by conceptual legal analysis. Such a methodology is rooted in the meticulous examination of both primary and secondary legal sources. The primary source includes the Constitution, statutes, by laws, regulations, judicial precedents, and treaties. Primary sources in this study are, in respect of Nigeria, the Constitution of Nigeria, the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) 2021, Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Host Communities Development Regulation 2022, Conversion and Renewal (Licenses and Leases) Regulation 2022, Petroleum Royalty Regulations 2022, Domestic Gas Delivery Obligation Regulations 2022, and associated policies. Conversely, those regarding Bangladesh are the Constitution of Bangladesh, Bangladesh Petroleum Act 1974, The Gas Act 2010, Natural Gas Safety Rules 1991, Gas Cylinder Rules from 1991, Gas Pressure Vessel Rules from 1995, and the Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) Rules 2004, Bangladesh Oil, Gas, and Mineral Corporation Act 2022, National Energy Policy (NEP) 2004, Income Tax Ordinance 1984, and Indigenous Natural Oil/Gas Exploration Policy. Apart from that, a few international conventions and treaties were also consulted such as the New York Convention 1992 and UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration 1985 and with amendments as adopted in 2006. In addition, the secondary sources encompass journal articles, law reviews, and reports from international organizations such as the International Energy Agency (IEA), the World Bank, International Renewable Energy Agency (IREA), World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD), and Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century (Ren21). Reports from international organizations are important to evaluate and assess the present energy scenario of both countries. This method aimed to ensure the reliability of the findings concerning Bangladesh and Nigeria’s oil and gas legal framework. The study also incorporated theories as a theoretical framework to guide the research.

For the literature review, we evaluated studies that focus on the legal and policy framework relating to energy sustainability, its determinants concerning SDG 7, and its implications for other related objectives in Bangladesh and Nigeria. The studies selected were in English, with no restriction on the publication year or setting. As mentioned, for secondary sources we incorporated recent reports, selected gray literature, systematic reviews, case studies, cross-sectional analyses, policy reviews, and pertinent experimental studies. For the research, databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, ScienceDirect, DOAJ, JSTOR, and Google Scholar were explored for peer-reviewed articles. Google search was employed for gray literature and to cross-reference papers under consideration. The papers and abstracts obtained through various search methods were then assessed for inclusion. Key search terms encompassed: energy sustainability, oil and gas, Bangladesh, Nigeria, legal and policy framework, renewable energy, energy efficiency, renewable energy technologies, socio-technical determinants, SDG 7, energy policy, and developing nations. While there is a vast body of literature on the subject, this review specifically hones in on studies pertinent to energy sustainability in alignment with SDG 7 in Bangladesh and Nigeria and the socio-technical determinants influencing the realization of SDG 7 and its associated goals.

A comparative legal analysis of the legal frameworks of the petroleum industry was conducted to assess the current regulatory structures of Bangladesh and Nigeria and promote innovative and sustainable technologies in energy and the environment in alignment with sustainability goals. This approach in legal research is consistent with the field of law and can be easily verified. Another rationale for utilizing this method was establishing the research findings’ trustworthiness. Further, comparative law is often hailed as the “analytical cornerstone of legal science” due to its meticulous approach in contrasting and analyzing legal systems or their components to discern similarities and discrepancies [

97]. Such comparative study can be conducted in two levels: the macro and micro levels [

98]. At the macro level, comparative law seeks to enhance the universal understanding and manifestations of law by studying patterns and contrasts [

97]. Conversely, at the micro level, the objective of comparative law is to facilitate the foreign-law research, promote law reform, and deepen comprehension of diverse legal systems. The current study employed both comparative macro and micro analyses. Comparative macro analysis helps in fostering legal reform and comprehending how alternative legal systems dovetail directly with the potential of forging new and adapting existing legal frameworks of Bangladesh and Nigeria. While micro comparative analysis would enable us to understand legal and policy frameworks in relation to the petroleum industry of both countries and their implications for facilitating the achievement of SDG 7 together with legal cultures, legal cultures refer to a “framework of intangibles within which interpretive communities operate and which have normative force for these communities… It occupies a middle ground between which is common to all human being (if, indeed, there be such commonality) and which is unique to each individual [

99].”

This type of research is crucial as many developing countries, including Nigeria and Bangladesh, lack the necessary capital and resources for oil and gas exploration and extraction. Therefore, involving investors in carrying out these activities on their behalf is vital, as suggested in the literature. Efficient and effective legal frameworks for oil and gas exploration in these two countries are essential to prevent potential conflicts between the government and investors. The choice of Bangladesh and Nigeria emerges from a recognized literature gap. Notably, while substantial research exists on developed countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, there remains a paucity of in-depth analysis concerning these two nations. The intention is to shed light on how their respective legal frameworks can propel them towards economic development, environmental sustainability, and greater employment prospects. Moreover, this research aims to gauge the readiness of their legal structures in achieving the benchmarks set by SDG 7. Furthermore, most studies on legal frameworks, particularly comparative studies, have been conducted in advanced countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom [

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105,

106]. Therefore, there is a need to bridge this gap by explicitly examining the legal frameworks and provisions within Nigeria and Bangladesh’s oil and gas industries to bring about economic efficiency and employment opportunities for both nations. Moreover, based on the current authors’ knowledge, there has been limited research on the necessity of a paradigm shift in the legal regime and policies concerning Bangladesh and Nigeria’s existing oil and gas legal framework and its contribution to achieving SDG 7. The present study could foster cross-border knowledge exchange and contribute to the objectives of SGD 7, promoting innovative and sustainable technologies and a better environment. Consequently, the comparative analysis aimed to provide an overview of the policies and institutional structures required to enhance energy efficiency through the utilization of low-carbon energy and to draw insights from international best practices in developing sustainable energy policies. The subsequent subheading presents the overall results and discussion of the study.

3. Results

This part analyses various policy documents relating to legal frameworks for oil and gas operations and activities in Nigeria and Bangladesh.

3.1. Legal Frameworks of Oil and Gas in Nigeria

Numerous regulations control the extraction and distribution of oil and gas in Nigeria. The fundamental legislations include the 1999 Nigerian Constitution (as amended) and the Petroleum Act. The latter entrust the Federal Government of Nigeria with possessing and supervising all petroleum resources found across the nation, regardless of their location—on land, under territorial waters, within the continental shelf, or its exclusive economic zone [

107,

108].

The Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) 2021 is one of Nigeria’s prime legislations regulating the petroleum industry. The purpose of enacting the Petroleum Industry Act is to establish a legal and regulatory framework for the Nigerian petroleum industry and to develop host communities and other relevant matters in the upstream, midstream, and downstream sectors. The said legislation harmonized all the legislations related to the petroleum industry and significantly overhauled the sector, particularly the functions performed by regulatory entities, to eliminate unnecessary duplication [

108,

109,

110]. The Nigerian Petroleum Industry has undergone a significant transformation by enacting the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA), which has effectively repealed or amended all previously existing laws governing the sector. As a result, the PIA has emerged as the principal legislation that now controls the operations and activities of the Nigerian Petroleum Industry [

83,

111,

112]. The Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) has clarified Nigeria’s petroleum industry’s fiscal and regulatory environment. This has led to a new wave of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the industry, hoping that other industry-related issues, such as infrastructure deficits and security (including crude oil theft), will be addressed [

113]. However, it is essential to note that the impact of the new energy transition on new investments in fossil fuels is still uncertain.

The Nigerian Minister of Petroleum (MoP) continues to exercise general supervision over the affairs and operations of the Nigerian petroleum industry under the pre-existing Petroleum Act (PA). However, Nigeria’s petroleum industry governance and institutional structure fundamentally differ from the pre-existing structure. Under the Petroleum Act (PA), the governance and administration of the Nigerian petroleum industry rest with the Nigerian Minister of Petroleum (MoP). However, the Minister had traditionally delegated certain functions to the Department of Petroleum Resources (DPR) or its predecessor agencies over the years. The DPR is a government agency within the Ministry of Petroleum, which makes it entirely dependent on and subject to the complete control of the MoP [

109].

Figure 7 shows the concerned regulatory authorities responsible for regulating the petroleum industry.

The PIA is arranged into five distinct Chapters (Governance and Institution, Administration, Host Communities Development, Petroleum Industry Fiscal Framework, and Miscellaneous Provisions), comprising 319 Sections and seven Schedules.

Figure 8 outlines the governance framework of the Nigerian petroleum industry. The first Chapter of the statute pertains to the governance and institution of the petroleum industry. It underscores that the Government of the Federation of Nigeria assumes the ownership and control of petroleum within Nigerian terrestrial and aquatic borders. The Petroleum Industry is spearheaded by the Minister of Petroleum Resources, endowed with the power conferred by Section 3(1) of the PIA to formulate, oversee, and administer government policies in the petroleum domain, among other functions.

The Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (the Commission) and the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Authority (the Authority) are regulatory bodies established by the PIA in the petroleum industry. The Commission, a body corporate with perpetual succession as provided in Section 4 of the Act, is responsible for supervising and regulating upstream petroleum activities, including technical and commercial regulations, and enforcing compliance with relevant laws and regulations. Conversely, the Authority, in accordance with Section 29(3) of the Act, is tasked with overseeing the technical and commercial regulation of midstream and downstream petroleum operations [

114].

Furthermore, Section 53 of the legislation established the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPC Limited). Its primary function is to serve as a representative of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), responsible for supervising the management of NNPC’s assets, interests, and obligations during their phasing out period [

109]. Section 65 of the Petroleum Industry Act establishes incorporated joint companies, including NNPC Limited. NNPC Limited must operate commercially and maintain profitability without relying on government funding, as stipulated in their memorandum and articles of association. Additionally, the company is obliged to distribute profits to its shareholders and retain 20% of its earnings for reinvestment, aligning with Section 53(7) of the Companies and Allied Matters Act, which applies to all incorporated entities.

Chapter 2 of the PIA aims to manage and improve the exploration and extraction of petroleum resources in Nigeria to benefit its people while promoting efficient growth of the industry. Section 67 of the Act stipulates the guidelines for managing and administering petroleum resources in a manner that upholds principles of sustainable development, transparency, and good governance within Nigeria.

As per Section 68 of the Act, data and analyses related to upstream petroleum activities are the property of the Government and overseen by the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission, which is in line with International best practices. All the data related to upstream rest with the Commission per the National Data Repository Regulations, 2020 [

114]. If petroleum is discovered in a frontier basin, the Minister, per the Commissioner’s recommendation, has the authority to designate some or all of the basin as a general onshore area. Consequently, following the reclassification, the fiscal terms that apply to onshore operations will be used for new licenses and leases within the basin. However, this rule does not apply to existing licenses and leases at the moment of reclassification [

83].

Only companies legally established under the Companies and Allied Matters Act and situated in Nigeria are qualified to obtain a lease or license. Section 70 of the Act modifies the names of current permits and leases pertaining to upstream petroleum operations and substitutes them with new ones, for instance, petroleum exploration licenses, petroleum prospecting licenses, and petroleum mining leases. The licensing round guidelines provide investors with the base terms essential for making investment and financial decisions. These terms include the acreage, term, details of guarantees to be provided, minimum work obligations, relinquishment, abandonment, dispute resolution, regulatory obligations, and fiscal terms of the license/lease ahead of any grant of such license. In accordance with Section 111, the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Authority is vested with the authority to approve, renew, modify, or extend individual licenses or permits.

Nevertheless, concerning the establishment of refineries, the Ministry shall only issue licenses based upon the advice furnished by the Authority. The Authority is bound by the Act to create regulations and guidelines regarding issuing and extending licenses for midstream and downstream activities involving petroleum. The issuance of petroleum licenses/leases marks a crucial milestone for Nigeria in its quest for a diversified economy anchored on crude oil and gas. Although the impact of this endeavor may not be readily discernible, its ramifications are expected to manifest progressively in the foreseeable future.

Furthermore, another important provision introduced by the PIA is the Petroleum Host Community Development (PHCD). The communities hosting petroleum-related activities play a vital role in guaranteeing the triumph of the petroleum industry. Therefore, compared to other communities, they are entitled to a favored position in obtaining direct social and economic advantages from these operations within their respective localities [

115]. Section 234 of the PIA stipulates the promotion of sustainable prosperity among host communities, furnishing them directly with social and economic benefits from petroleum operations and establishing a framework for supporting their development. Section 235 of the Act also permits the establishment of host communities development trusts (HCDT), which the settler must form to benefit its responsible host communities within a specified timeframe. Sections 240 and 244 of the Act delineate the sources and allocation of the host communities’ development trust, which is to be fairly distributed by the Board of Trustees among the host communities, employing a matrix provided by the settler [

116]. It is crucial for the government and regulatory bodies to pay close attention to the deployment of HCDTs in the Niger Delta and other oil-producing regions, as their successful implementation is essential in ensuring peace and optimizing oil production output. The increase in oil production volumes, mainly when oil prices are rising, can help increase government revenue, allowing for the funding of vital infrastructure projects and minimizing the requirement for additional borrowing [

117].

The PIA has introduced a new fiscal framework for the existing petroleum industry, for instance,

The separation of upstream, midstream, and downstream assets into distinct companies for taxation purposes.

A reduction in income tax and royalty rates can be observed, contingent on the level of production achieved.

There is a restriction on the deductibility of expenses for tax purposes, which limits the amount to a maximum of 35% of gross revenues that can be claimed.

Interest, litigation, arbitration, and bad debt expenses are not eligible for tax deductions.

PIA has also incorporated a royalty system based on pricing for crude oil collection and condensates from all contracted regions. The royalty will come into effect when the price per barrel surpasses USD 50 and will be deposited into the Nigerian Sovereign Wealth Fund. Further, PIA has implemented a dual-level fiscal system for companies engaged in upstream petroleum activities, specifically Hydrocarbon Tax (HT) and Companies’ Income Tax (CIT). HT generally applies to profits accrued from the crude oil, field condensates, and liquid NGLs produced from associated gas (AG) as long as the underlying fields are situated in onshore or shallow water acreages. Notably, profits generated from the frontier and deep offshore acreages are exempted from HT. In contrast, CIT is levied on all profits, irrespective of whether they are under the purview of HT or not. Additionally, midstream and downstream operations’ profits solely attract CIT while being exempt from HT [

118].

The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 is an essential basis for the operation, ownership, and control of oil, gas, and other vital mineral resources. Article 44(3) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended), postulates that oil and gas ownership, control, and management are exclusively for the federal government’s authority. This position in the constitutional basis of the country strongly posits that the government has the right to oil and gas on behalf of the entire citizens of the country for the advantages and overall development under the provision of the legal framework. Nonetheless, the current scenario of lack of good governance and corruption affects the extent by which the country has been able to judiciously use the revenue from oil and gas for the benefit of the citizens and overall development of the country [

87,

117,

119] when compared with what is obtainable elsewhere like Abu Dhabi, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirate, etc.

Apart from the Constitution and PIA, other legislations directly impact, govern, and regulate the oil and gas industry. For example, the Petroleum Profit Tax Act outlines the framework for obtaining revenue from companies involved in these sectors through royalties, taxes, and signature bounces. The Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) Establishment Act of 2007 empowers FIRS to gather payments in various forms, including but not limited to taxes, royalties, rents, penalties for gas flaring, and depot fees. This Act allows FIRS to collect license fees such as oil mining and prospecting, signature bonuses, and other charges. The Education Tax Act imposes 2 percent assessable profits on oil and gas companies for developing the Nigerian education sector. The Niger Delta Development Commission (Establishment) Act obligates oil and gas companies to pay 3 percent of their annual budget to foster the advancement of the Niger Delta region where oil and gas are exploited.

The National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (Establishment) Act establishes the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA) responsible for coordinating and implementing the National Oil Spill Contingency Plan. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Act outlines the framework for evaluating the potential impact of oil and gas exploration on the environment. The Nigerian Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative Act 2007 ensures transparency and accountability in reporting and disclosing revenue due to or paid to the Federal Government by the exiting oil and gas companies. The Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry Content Development Act 2010 provides the framework to stimulate the participation of Nigerian nationals in the oil and gas sector by delineating the essential conditions for utilizing local resources in the industry [

79].

Apart from this legislation, the Commission and the authority are regularly issuing various regulations and guidelines, i.e., Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Host Communities Development Regulation 2022, Conversion and Renewal (Licenses and Leases) Regulation 2022, Petroleum Royalty Regulations 2022, Domestic Gas Delivery Obligation Regulations 2022, to amplify the PIA spell out details relating to implementation. Nigeria has adopted close to 20 policies to promote energy sustainability. Notable among them are the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement 2021, the Nigerian Economic Sustainability Plan 2021, Nigeria’s National Action Plan to Reduce Short-lived Climate Pollutants 2019, the Flare Gas (Prevention of Waste and Pollution) Regulation 2018, the National Gas Policy 2017, and the National Petroleum Policy 2017, among others [

76]. However, It is worth noting that the implementation of these policies has not been particularly significant.

The PIA has believed to have a significant impact on the Nigerian petroleum industry by establishing a framework that is more conducive to the sustainable growth of this sector. But there is still doubt that the nascent legislation would promote the objectives of SDG 7 because the present PIA has made no mention of energy sustainability or renewable energy, or energy technologies. Although Nigeria is one of the petroleum countries in Africa, it is still struggling to meet its country’s demand by providing affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all citizens. Therefore, it is paramount for the government to give equal attention to renewable and sustainable energy and the petroleum industry that empowers people to have affordable energy access and buy low-cost energy technologies as mandated by SDG 7.

3.2. Legal Frameworks of Oil and Gas in Bangladesh

Bangladesh has established a regulatory framework to govern the exploration and production of oil and gas. The framework includes provisions for technical expertise and strategic planning for exploration, which is essential given the limited knowledge and capital available to extract these resources. The regulatory framework ensures that exploration and production activities are conducted safely and sustainably while promoting sector investment. However, the lack of technical knowledge and financial resources poses a significant challenge to developing and extracting oil and gas in Bangladesh [

90]. The legal framework governing oil and gas exploration and production in Bangladesh allows for partnerships between the government and international oil companies, particularly in offshore areas, to facilitate sufficient exploration and production. As per the financial year of 2018–2019, the legal provisions require local production companies to contribute 39.12% towards the total oil and gas production. However, the remaining 60.88% is designated for international oil companies (IOCs). Notably, Chevron, an IOC, has a significant role in producing over 60% of the country’s natural gas and 80% of its condensates. These figures highlight the substantial contribution of IOCs towards the overall oil and gas production in Bangladesh [

120].

Primarily, the legal framework of the petroleum industry is laid down by the Constitution of Bangladesh. Article 143 of the Constitution stipulates that all minerals underlying any land or ocean within the territory of Bangladesh shall vest in the State. Therefore, all petroleum resources explored and produced by national or international companies will belong to the country [

121]. The first noteworthy legislation concerning the discovery of oil and gas is the Bangladesh Petroleum Act 1974 (BPA 1974). According to this Act, the government holds exclusive authority over the exploration, exploitation, and production of oil, gas, and petroleum within the country’s territorial jurisdiction or economic zone. Petroleum is defined under the Act as any natural hydrocarbon or a mixture of hydrocarbons in a gaseous, liquid, or solid state containing one or more hydrogen sulfide, nitrogen, helium, and carbon dioxide.

The BPA (1974) permits the government to enter into contracts or agreements for petroleum exploration with local or foreign investors. In other words, no individual or entity can undertake petroleum exploration and production activities without a contractual agreement or license approval, typically established through a production sharing contract (PSC), the governing mechanism allowing operators to conduct exploration and production activities in Bangladesh. The Onshore Model PSC 2019 and Offshore Model PSC 2019, which have received government approval, serve as sound references for potential investors. Although certain aspects of the PSCs, such as profit-sharing arrangements, will require negotiations with the government, the majority of the terms and conditions outlined in the models, as mentioned earlier, will remain consistent in any corresponding PSCs agreed upon with the selected operator [

122]. The BPA (1974) highlights the duties and obligations of contractual parties involved in oil and gas exploration activities, and violations of the provisions contained in the Act may result in penalties. It is important to note that Petrobangla, representing the government’s interests, typically engages in discussions with various international oil companies (IOCs) regarding production-sharing contracts (PSCs). Therefore, compliance with the BPA (1974) provisions is of utmost importance for all parties involved in oil and gas exploration activities in Bangladesh.

In line with the legislative framework of the energy sector in Bangladesh, the Petroleum Act (2016) is another notable legislation that regulates the importation, transportation, storage, production, refining, processing, marketing, and distribution of petroleum. The Act emphasizes the need for obtaining a license before engaging in any investment or business activities in the oil and gas sector, particularly importation, transportation, and distribution. Any violation of the provisions contained in the Act is punishable by the government. To effectively enforce the Petroleum Act (2016), the Ministry of Power, Energy and Mineral Resources (MPEMR) introduced the Petroleum Rules (2018), which outline comprehensive guidelines for the application procedures and requirements for obtaining licenses as stipulated in the Petroleum Act (2016). The guidelines cover various methods for the importation of petroleum, as well as approval procedures for the establishment of refineries and petrochemical plants [

116].

In 2019, the Ministry of Power, Energy, and Mineral Resources (MPEMR) in Bangladesh launched the Indigenous Natural Oil/Gas Exploration Policy to address the country’s over-dependence on imported oil and gas. The policy also aims to integrate modern technological facilities for exploration purposes. As highlighted in the policy, state-owned oil and gas companies should be made more efficient and effective. Bangladesh Petroleum Exploration Company Limited (BAPEX), Bangladesh Gas Fields Company Limited (BGFCL), and Sylhet Gas Fields Limited (SGFL) are some of the indigenous oil companies tasked with implementing standard procedures for oil and gas operations [

123].

The Gas Act (2010) explicitly regulates the transmission, distribution, marketing, supply, and storage of natural gas and liquid hydrocarbons within Bangladesh’s territorial jurisdiction and economic zones. The primary objective of the Act is to ensure the proper utilization and regulation of different mineral substances. It is important to note that the Gas Act (2010) does not cover the exploration and production of natural gas and other resources, as the Petroleum Act comprehensively governs these aspects. Additional legislation relevant to Bangladesh’s gas sector comprises the Natural Gas Safety Rules 1991, Gas Cylinder Rules from 1991, Gas Pressure Vessel Rules from 1995, and the Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) Rules 2004.

Apart from that, the government recently re-enacted the Bangladesh Oil, Gas, and Mineral Corporation Act 2022, replacing the Bangladesh Oil, Gas, and Mineral Corporation Ordinance 1985. The corporation will be called Petrobangla and the responsible authority to carry out the purposes of the Act. Petrobangla will be incorporated as a legal body capable of maintaining perpetual succession, possessing a common seal, and with authority to acquire, own, and sell movable and immovable property. It will also be able to initiate legal proceedings and defend itself under its registered name. Petrobangla plays a significant role as Bangladesh’s main regulatory body for upstream oil and gas. Petrobangla operates under the authority of the Ministry of Power, Energy and Mineral Resources (MPEMR) and performs various functions, including researching oil, gas, and mineral resources, as well as exploration and development. It is also responsible for representing the government in production-sharing contracts (PSC) with local or foreign oil companies. Additionally, Petrobangla is mandated to conduct geological and geophysical surveys on the exploration and development of oil, gas, and mineral resources [

124].

The energy transmission system is a critical component of the economic development of Bangladesh’s oil and gas sector. To this end, the government introduced the National Energy Policy (NEP) in 2004, which seeks to facilitate adequate exploration, distribution, and production using various energy sources to meet the growing domestic energy demands and promote rapid development. The NEP (2004) encourages foreign and local investors to participate in the country’s petroleum exploration [

123]. Furthermore, the legal framework governing the sector highlights the importance of production-sharing contracts (PSCs) in offshore areas. It provides exemptions for duties on machinery, equipment, and consumables used in petroleum operations during exploration, development, and production. Tax under the PSCs terms is also exempted. The Speedy Supply of Power and Energy (Specifically Provision) Act 2010 was enacted to ensure uninterrupted power supply and energy and to facilitate increased production, transmission, transportation, and marketing of power and energy in the sector [

92].

The New York Convention of 1992 holds significant importance in international arbitration, and Bangladesh is among the signatories to the Convention. In order to demonstrate its commitment, the country formulated the Arbitration Act of 2001, which incorporates two crucial elements—The New York Convention and the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration. Bangladesh’s commitment to the Convention and International Arbitration is demonstrated by its ratification for the purpose of Pacific Settlement of International Disputes. The country is also considering the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of other States. To promote efficiency in the oil and gas sector, experts have advised the government to sign the Singapore Convention on Mediation as it will encourage foreign direct investment and foster amicable approaches for the reconciliation of commercial disputes between the State and the investor.

In 1984, the Income Tax Ordinance was introduced in Bangladesh, enabling the government to enter into treaties with other countries to avoid double taxation. As a result, Bangladesh has signed several treaties relating to double taxation avoidance with many countries, including China, Japan, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, the United States, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, and others.

4. Discussion

Oil and gas supplies have a crucial role in the energy market; the petroleum and gas industry’s technology, including intelligent boiling systems, smart oil and gas fields, and automated maritime platforms, has evolved rapidly for years. The oil and gas sector is increasingly progressing towards intellectualization, digitization, and automation in the management mode. This model has low performance, high cost, long-term, and high-risk characteristics [

125]. Over the course of its tumultuous history, the oil and gas industry has undergone significant transformations driven by factors such as technological advancements, globalization, and changing demographics. In recent years, the industry has faced numerous challenges, including a sharp downturn in the aftermath of the global economic and financial crisis, a collapse in demand caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and increased supply volatility and prices following the Russian Federation’s aggression against Ukraine. Similarly, it is important to mention that variations in energy policy, socioeconomic development, socio-political condition, and environmental consideration would undoubtedly influence the exploration, extraction, and consumption of natural resources in Bangladesh and Nigeria.

It is apparent from the discussion before that Nigeria’s and Bangladesh’s economies heavily depend on oil and gas. The majority of Bangladesh’s primary energy demand is derived from its limited natural gas reserves [

126]. Around two thirds, or approximately 65%, of the overall electricity production relies on natural gas, as cited in sources [

127,

128]. The Statistical Review of World Energy predicts that Bangladesh’s remaining natural gas reserves, estimated at 7.25 trillion cubic feet (Tcf), will be depleted within the next ten years [

129]. Similarly, petroleum accounts for over 78% of total energy consumption [

130].

Further, the majority of electricity generation in Nigeria comes from gas and hydro, which have proven insufficient to meet the required demand of the country. Around 77% of Nigeria’s electricity is produced from natural gas [

131]. Therefore, it is apparent that both countries’ primary energy consumption relies heavily on petroleum. Utilizing a diversification strategy for ensuring energy security takes into consideration a greater quantity of appropriate primary energy sources. Broadening the energy spectrum by integrating diverse, sustainable, low-carbon alternatives stimulates economic advancement and safeguards the environment [

132].

Therefore, both countries must develop a conducive energy policy framework to excel in their economy while protecting natural resources. The pursuit and ability to manage energy resources have played a vital role in geopolitical affairs and global wars and conflicts and remain significant to this day. In addition, the worldwide oil and gas industry shares common features to the extent that significant operators, sub-contractors, and others within the value chain operate with similar equipment and similar exploration, drilling, and production procedures that are subject to similar industrial standards and documentation created by a network of expert actors and an international scientific and technical community [

100,

133]. Consequently, Bangladesh and Nigeria have consistently strived to protect and utilize their natural resources for economic benefits while fulfilling the present energy demand.

The legal basis for oil and gas exploration, development, and production of both Bangladesh and Nigeria is established in the Constitution. The constitution of both countries explicitly specified that the republic owns and manages petroleum resources, and the government, on behalf of the people, will manage the said resources. Although the Constitution provides many provisions relating to natural resources, the Constitution does not give a detailed governance mechanism for operating the industry. Domestic laws and regulations contain the details of the administrative, governance, and fiscal structure for operating the petroleum industry. The legal and regulatory framework governing the petroleum industry is primarily defined by domestic laws and regulations, which hold a central position in this context.

Any policy related to economic, political, and societal goals will bring community goods [

134]. Nigeria has recently passed the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) 2021 in considering the policy objective. The PIA is believed to be the exemplary model for effective natural resource management by outlining the distinct and well-defined roles of the different subsectors within the industry. Additionally, the Act emphasizes the need for a profit-driven national petroleum company, transparent and accountable administration of the country’s petroleum resources, the socio-economic upliftment of host communities, environmental restoration, and a favorable business environment for the successful operation of oil and gas activities in Nigeria [

79,

83,

112,

114,

135]. The assertion of the gold standard of the present PIA is not entirely unrealistic or baseless because the Act is nearly 20 years of effort to reform the Nigerian Petroleum industry to create a more conducive environment for the industry. On the other hand, unlike Nigeria, Bangladesh has several legislations that regulate the petroleum industry. However, the Bangladesh Petroleum Act 1974 and Petroleum Act 2016 are the prime legislation regulating the petroleum sector.

It is apparent from the above discussion that the PIA 2021 of Nigeria is more comprehensive compared to Bangladesh’s legislation relating to the petroleum industry. The PIA 2021 of Nigeria addresses significant steps toward reform of the NNPC governance structure to make it more effective in managing upstream, midstream, and downstream operations. The PIA is made two separate institutions upstream, midstream, and downstream, the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (the Commission) and the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Authority (the Authority) [

117]. On the other hand, Petrobangla is the only authority in Bangladesh responsible for managing the upstream, midstream, and downstream operations. In addition, the provisions relating to fiscal infrastructure, environmental management, and development of host communities in the PIA of Nigeria are more comprehensive and progressive than the present regulatory framework of Bangladesh. For example, BPA 1974 does not adequately address the environmental issues in exploration. The said Act merely mentions that the person engaged in any petroleum operation shall consider the adverse impact on ecology and the environment. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the Act does not establish any explicit liability for environmental harm resulting from the negligent actions of mining companies.

It is important to understand that the exploration, development, and production of oil and gas have the potential to generate adverse socio-economic and cultural effects, which may include alterations to land-use patterns, violations of human rights, and harm to cultural heritage and biodiversity [

136,

137]. Indigenous communities residing in remote areas with distinct lifestyles and values are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of petroleum exploration compared to other communities. The operations may result in the displacement of local inhabitants from their traditional lands, the destruction of their cultural foundation, and environmental pollution of their habitat. While some of these negative consequences are inevitable outcomes of the mining process, others may be attributed to unsustainable practices and negligence of operating companies towards the local communities [

138]. Therefore, it is crucial to address environmental and social issues. However, Bangladesh’s Environmental Conservation Act 1995 provides provisions for the environmental impact assessment of all mining projects, but it fails to address the social impact.

In contrast to the Nigerian legal framework, the Bangladeshi legal system has yet to effectively address host communities’ development in the context of natural resource development. The involvement of the local community in the exploration and production of gas and oil are crucial. As such action can significantly affect local people’s traditional way of life, it is essential to incorporate them into the project development and implementation to avoid any adverse impacts and mitigate public outrage towards the project. Therefore, ensuring public participation in such development projects can effectively address the concerns of the local communities and facilitate a sustainable and inclusive approach to petroleum exploration [

116,

138]. Consequently, it is no surprise that the PIA of Nigeria has emphasized the local community’s participation through several provisions. Apart from the petroleum law, other laws and regulations are in operation that facilitate petroleum operations both in Nigeria and Bangladesh. Petroleum law and other related laws and regulations should be coherent with each other and with international laws, norms, and customary rules prevailing in the country for the smooth operation of the petroleum industry.

The question is whether Bangladesh and Nigeria’s present oil and gas legal framework is conducive to attaining SDG 7. An integrated and well-articulated policy framework is imperative to achieve energy transition and sustainable development [

128,

139,

140,

141,

142]. The current regulatory frameworks of Bangladesh and Nigeria for sustainable clean energy are inadequate, lacking the necessary strength. Additionally, there is limited coordination among governments, regulatory agencies, and industry stakeholders when establishing and enforcing sustainability standards. This gap extends beyond industrial emissions and encompasses areas such as green public procurement.

Furthermore, insufficient infrastructure, financing, knowledge, and information pertaining to clean energy in industrial activities hinder research, development, and deployment in these areas. As the global average temperature has already surpassed 1.2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the urgency to transition to sustainable energy systems becomes paramount [

143]. Failing to make this transition poses severe risks to both human wellbeing and economies, with consequences that may persist for decades. It is imperative that we accelerate the pace of implementation significantly, aiming to build a resilient and sustainable world.

Currently, global attempts to combat climate change may heavily rely on the usage of resources and the release of emissions from industrialized and urbanized nations located far from the leading edge of energy consumption and have less strict environmental policies [

144,

145]. Encouraging efficient resource usage and developing environmentally friendly products are crucial in addressing concerns related to the environment and limited resources. The countries need to devise an innovative policy and prioritize their policy strategies. Developing countries like Bangladesh and Nigeria must utilize advanced technology to improve energy efficiency and accelerate the transition [

118,

146,

147]. As a party to the Paris Agreement, Bangladesh and Nigeria must reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to limit the global temperature increase. The global impact of the Paris Agreement on oil refineries is substantial, as it plays a crucial role in reducing CO

2 emissions through the implementation of stricter policies and emission caps. Since oil refineries make a significant contribution to CO

2 emissions, it is imperative for all oil-exporting nations to adhere to these regulations. To align with the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement, Bangladesh and Nigeria must proactively adopt environmental policies to mitigate the environmental impact of their oil sector activities and implement effective emission control strategies to foster a more environmentally friendly oil industry [

148].

Although Bangladesh and Nigeria do not have sufficient capacities like developed nations to combat many challenges brought by climate change, both countries could contribute to such causes by reducing their dependency on fossil fuels to minimize the emission of harmful greenhouse gases, which significantly contribute to global warming and climate change. It would not be easy to reduce the usage of fossil fuels in Nigeria and Bangladesh, considering the heavy use and economic dependency on such fossil fuels.

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 give a glimpse of both countries’ energy consumption by sector.

According to the Sustainable Development Report 2020, Bangladesh is making moderate progress in achieving SDG 7 but insufficiently attaining the goal. However, Nigeria’s progress in the same area appears to stagnate or increase at less than 50% of the required rate [

149]. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that Bangladesh has demonstrated remarkable progress in implementing the SDG. In the SDG Index and Dashboards Report, Bangladesh ranked 101 out of 163 countries, reflecting its commitment and advancements towards the SDGs. Conversely, Nigeria ranked 146, indicating the need for more significant efforts and improvements in the country’s SDGs implementation [

149]. Although Bangladesh has made considerable progress in implementing SDG 7 compared to Nigeria, both countries still need to take substantial initiatives to realize the SDG 7 goal.

Table 1 shows a comparative overview of both countries’ socio-economic situation and the present energy regulatory landscape.

The policymakers must understand that sustainability revolves around delivering clean and efficient energy services while minimizing environmental harm. It encompasses utilizing and advancing renewable energy resources and raising concerns about their availability, distribution, and appropriateness [

150,

151,

152]. Furthermore, the challenges of expanding energy access to all individuals, including those residing in remote areas, remain unattainable given the existing socio-economic and settlement conditions. Off-grid energy solutions are unable to provide a viable and cost-effective resolution to this issue. Therefore, to accomplish sustainable development goals, it is imperative to understand the connection between energy access and socio-economic justice, which is marked by households’ economic and social autonomy. Improving access to a modern and sustainable energy supply system is an indispensable component of sustainable development agendas rather than an optional one [

9,

42].

While raising consumer-level awareness and promoting behavior changes can help mitigate the impacts of certain issues under favorable conditions, this approach should be supported by concrete policies and regulations from the industry, commerce, and government. Such initiatives are necessary to eliminate structural, economic, and social impediments that hinder the advancement and promotion of more accessible alternatives. Thus, a comprehensive approach involving multiple stakeholders and addressing underlying factors is crucial for achieving sustainable solutions [

153]. Although Nigeria and Bangladesh have made significant progress in the energy transition, the countries still lag behind the global averages in terms of improvement in energy and greenhouse gas emissions. As developing countries with limited resources, making an outright energy transition and achieving energy efficiency is daunting. It is crucial to adopt energy management strategies considering all possible demand- and supply-side options when making energy supply–demand policies and investment decisions. These strategies should align with global sustainability objectives, as they are essential for achieving a sustainable energy future.

Establishing a foundation for sustainable energy that aligns with environmental sustainability can be achieved by integrating energy efficiency and renewable penetration. This can be facilitated by implementing effective policies and programs. Countries worldwide are moving towards sustainable energy sources such as solar power, wind power, bio-energy, hydropower, geothermal, and ocean energy to guarantee energy security due to the finite reserve of fossil fuels and their negative environmental impact [

154]. A fundamental aspect of any sustainable energy strategy revolves around envisioning improvements in providing and utilizing energy, intending to contribute to sustainable development. Both Nigeria and Bangladesh have the depletion of conventional energy resources, significantly impacting their economic growth and development. Although Nigeria recently enacted PIA to accelerate its petroleum industry, the legislation fails to address energy transition and diversification adequately. Similarly, Bangladesh has also failed to capitalize on energy transition despite its recent energy crisis. Therefore, it is apparent that both countries still have to develop, amend, and integrate efficient policies into the present regulatory framework to accelerate the achievement of SDG 7.

5. Summary and Conclusions

Both Bangladesh and Nigeria, despite their distinct trajectories, are intricately tied in their shared challenge of achieving energy sustainability within the labyrinthine petroleum industry. They have enshrined regulatory frameworks, a reflection of their commitment to fostering investor confidence, thereby driving investments in their respective petroleum sectors. However, both nations’ oil and gas sectors have been stymied by challenges like low investment, high funding costs, operational uncertainties, and transparency deficits. Despite these hindrances, both have established decent energy infrastructures, albeit with a significant reliance on fossil fuels. Their shared challenge now is achieving energy efficiency and a progressive energy transition amidst their dwindling natural reserves.

While Nigeria’s Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) seeks to overhaul its oil and gas sector, emphasizing fiscal regimes in light of potential FDI losses due to uncertainties, Bangladesh boasts a robust energy policy framework. Conversely, in Bangladesh, even with an abundance of energy policies established, the government seems to be lagging in realizing its targeted outcomes, particularly in align with SDG 7. It is worth noting that while Nigeria and Bangladesh have adopted 20 and 10 energy-related policies, respectively, there is a discernible lack of sincere and substantial efforts to put these policies into action.

In addition, both nations grapple with the practical implementation of energy efficiency and transition, even as their natural reserves deplete. Their shared commitment to the Paris Agreement underlines the urgency of diversifying energy sources to align with 2030 climate change mitigation goals. The increasing global urgency surrounding renewables, epitomized by solar and wind energy, beckons these nations to transition from being mere observers to active participants in this global renewable energy surge. Such a shift is not just environmental but deeply economic, with clear linkages between energy consumption patterns, emission levels, and overall economic health. Furthermore, comprehending the nexus between energy consumption, emissions, and economic growth is paramount. Policy frameworks should foster a balance between state interests as resource proprietor/regulator and the interests of the petroleum firms. A nation’s policy stance, particularly in resource exploitation, arises from intricate interplays of factors like mineral potential, geopolitical positioning, political stability, and infrastructure levels. Merely leaning on policymakers’ intuition without understanding this complexity can be detrimental.

Both Bangladesh and Nigeria’s current regulatory structures for sustainable clean energy remain deficient, with a palpable absence of cohesive coordination among governments, regulatory bodies, and industry stakeholders. This coordination gap spans beyond just emissions, infiltrating realms such as green public procurement. Notably, while obstacles like infrastructural inadequacies, funding deficits, and knowledge gaps impede clean energy research and deployment, Bangladesh has manifested significant progress in the SDG sphere, ranking 104th out of 163 countries in the SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2022. In contrast, Nigeria’s 139th rank underscores its need for intensified SDG efforts.