An Interdisciplinary Scoping Review of Sustainable E-Learning within Human Resources Higher Education Provision

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Defining Sustainable E-Learning

1.2. Contributions and Shortcoming of Previous Systematic Literature Reviews on Sustainable E-Learning

1.3. Motivations for This Work

1.4. The Main Contributions of This Work

- As a contribution to the literature gap in the field of sustainable e-learning HR tertiary provision;

- As an aid to new and upcoming researchers within the discipline of HR higher education provision, who wish to study and expand the research into the contemporary state of sustainable e-learning within HR higher education across the university sector, globally;

- As reference point for more established academic researchers in the field;

- As a contemporary overview of the complexity of the sustainable e-learning HR tertiary provision—encompassing benefits, challenges, and future directions.

1.5. Aim, Research Question, and Objectives

- What is known about sustainable e-learning HRHE provision within the literature in terms of themes, benefits, challenges, and future directions?

- Identify the sustainable e-learning research themes within the HR- and interdisciplinary-related literature;

- Examine the most common contexts within which sustainable e-learning tertiary education is being undertaken more widely in the interdisciplinary literature, given the gaps in the HRHE e-learning literature;

- Provide a baseline for other researchers wishing to contribute to and expand the research into sustainable e-learning, within the specialist field of HRHE provision;

- To determine whether there is a case for undertaking a systematic literature review in the future in order to expand the results of this scoping review.

2. Review of Methodology

2.1. Philosophical Position

2.2. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews

2.3. The PRISMA-ScR Checklist

2.4. The PRISMA-ScR Protocol Framework

2.5. Preliminary Literature Search

2.6. Scoping Review

2.6.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

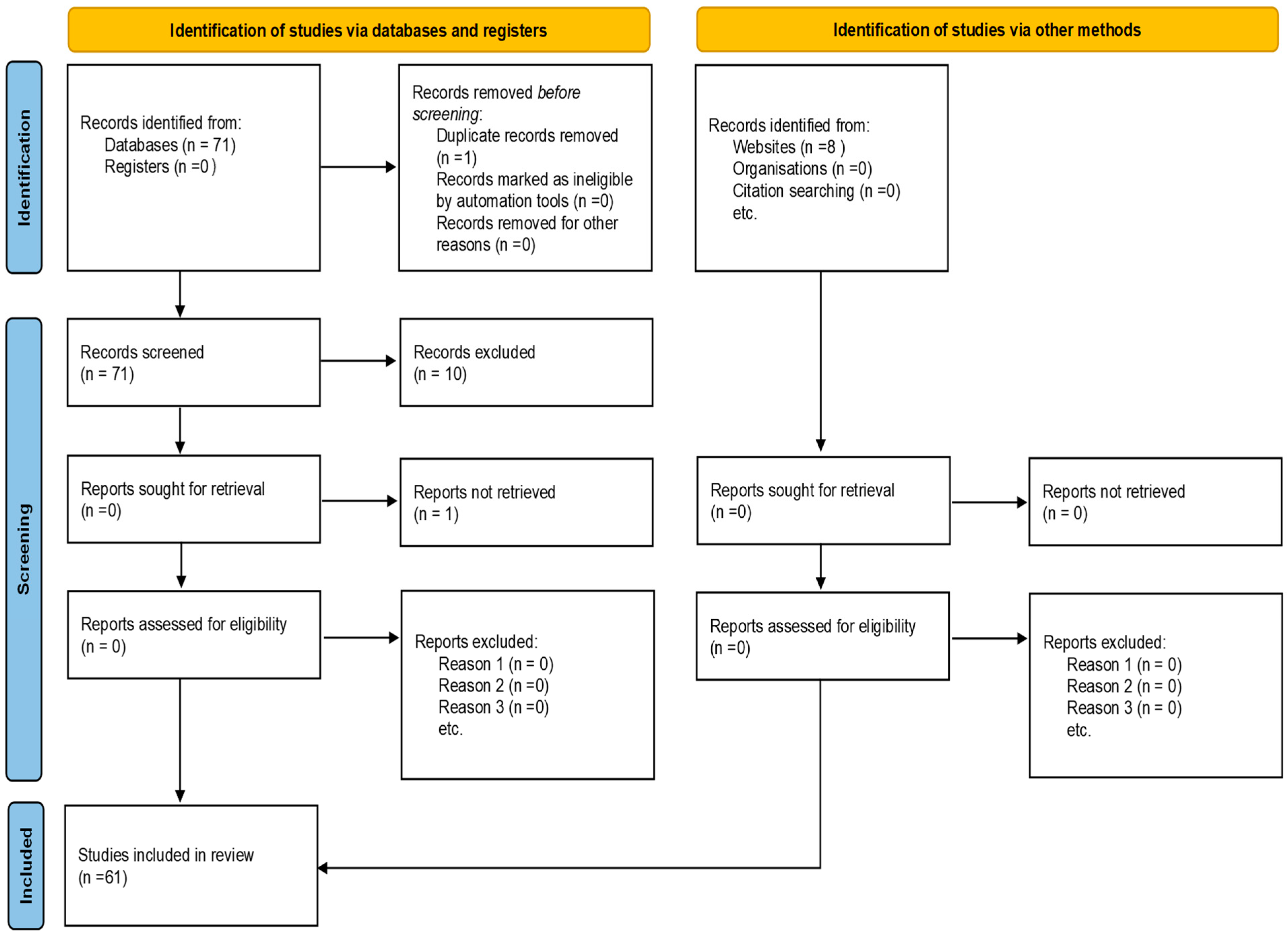

2.6.2. PRISMA—Flowchart to Identify Publications and Reports Included within the SCR

2.6.3. Data Charting Process (Categories and Units)

- Comprehend large and disparate forms of qualitative data;

- Integrate related data from different texts and notes;

- Identify key themes and patterns for further exploration;

- Develop theories based upon these patterns and themes;

- Draw conclusions.

2.6.4. Units

2.6.5. Data Items

2.6.6. Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

2.6.7. Synthesis of Results

3. Results Section

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

3.2. Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

3.3. Percentage of Publications by Database

3.4. Themes: Preliminary Search

3.5. Critical Appraisal within Sources of Evidence

3.6. Results of Individual Sources of Evidence and Synthesis

4. Discussion

4.1. Preliminary Search—Discussion

4.1.1. Terminology

4.1.2. Technology: Access, Equity, Space, Quality Assurance, and Economic/Socio-Demographics

4.1.3. Artificial Intelligence

4.1.4. E-Learning Space and Presence

4.1.5. Institutional E-Learning Responsibilities

4.2. Scoping Review—Discussion

4.3. Summary of Evidence: Challenges and Benefits and Addressing the Research Question

5. Limitations

- When using a protocol, it is recommended that thought is given to registering it with co-authors/fellow researchers in order to seek feedback from them regarding the overall appropriateness of the protocol;

- While this scoping review was undertaken by a single author. There is merit in collaborating with other reviewers, to aid objectivity, should a systematic literature review be undertaken in the future;

- This scoping review was aimed at providing an initial contribution to the literature gap identified at the outset of this paper. The suggestion is made that consideration could also be given to undertaking a more extensive systematic literature review and meta-analysis of sustainable e-learning HRHE provision, in order to further aid this research field;

- It is also noted that the use of the most recent version of NVivo/equivalent software would help aid efficiency of coding and minimise the time required to manually code each publication;

- Having more than one reviewer involved with a scoping review would also enable more reviewers to be involved in checking and approving the list of publications considered within the review;

- It is also noted this scoping review focused upon identifying the challenges, benefits, and future directions of sustainable e-learning in HRHE provision. In any future expansion of this paper, it is suggested that methodological design comparisons between publications could also be included in the review.

6. Conclusions

7. Future Directions

- Firstly, uni-generational versus inter-generational design influences: the traditional influence shaping e-learning contexts from processes, setting, content through to academic staff proficiency, and student satisfaction levels is shaped by a focus upon one generation at a time—the generation forming the student body in any given provision cycle. However, as this paper has highlighted, inter-generational satisfaction levels with e-learning processes differ from generation to generation, inferring more complex reasons for such differences. As such there is a need for more academic attention to be paid to investigating the drivers and impacts of those differences upon HEI e-learning provision, long-term, if e-learning is to be sustained ethically and with relevance for future cohorts, staff groups and society at large;

- Secondly, the AI dimension that is emerging through chatbots such as ChatGPT is the single most pressing matter, which the e-learning academic community and sector appear to be facing. The urgency is coming not just from the speed with which the software is developing—at a pace quicker than HEIs can strategise about e-learning practices and frameworks— but also coming from the imminent threat to human involvement within the e-learning process, which is causing one of the greatest ethical and interdisciplinary concerns within the HE sector, globally. Quite literally the question about whether or not there is a need for the human factor in the future to enable e-learning to be sustained is beginning to be articulated. A question that, this paper contends, now demands immediate and robust investment and academic attention across both scholarly and research activity;

- Thirdly, it is suggested that much research remains to be done on the complex infrastructure needed if e-learning within tertiary education is to be sustainable, including innovative technology such as block-chain, as well as addressing the structure and ethical issues arising from sustainable e-learning practices and institutional responsibilities, long-term. This should consider the pedagogical roots of e-learning and the ongoing development of academic staff and students in e-learning practices but with the appropriate level of attention given to ethical parameters. Amid the rising societal popularity of sustainable e-learning matters—where researchers are encouraged to avoid being swept along in populist narratives—appropriate methodological candour is needed. This will help to ensure learners and HE institutional needs given due attention;

- HRHE provision: There is also scope for HR researchers and HR educationalists to consider greater scrutiny of sustainable e-learning practices as they apply to HRHE provision directly. This will enable the specialist field of HRHE provision to be better supported with niche research and scholarly work and will minimise the need for reliance on interdisciplinary sustainable e-learning research to determine the quality of research as it pertains specifically to HRHE provision;

- A future SLR: Finally, it is suggested this review has provided a case for a full systematic review of literature to be undertaken in the future to further aid researchers in the field of HRHE provision who are interested in studying sustainable e-learning further. It is also suggested that this will provide an added baseline and reference point for academics in the field. It is also suggested that it will help contribute to the existing gap in the literature in relation to sustainable e-learning within the HRHE provision.

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Universities UK. How Universities Can Attract Vital Regeneration and Development Funding for Their Regions. Universitiesuk. 2022. Available online: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/latest/insights-and-analysis/how-universities-can-attract-vital (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- White, D. A Desituated Art School (A Provocation). 2020. Available online: https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/16494/2/Desituated%20Art%20School%20%28a%20provocation%29.mp4 (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Belluigi, D.Z. Why decolonising “knowledge” matters: Deliberations for educators on that made fragile. In Higher Education for Good: Teaching and Learning Futures; Czerniewicz, L., Cronin, C., Eds.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2023; 17p. [Google Scholar]

- Valverde-Berrocoso, J.; Garrido-Arroyo, M.d.C.; Burgos-Videla, C.; Morales-Cevallos, M.B. Trends in Educational Research about e-Learning: A Systematic Literature Review (2009–2018). Sustainability 2020, 12, 5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, H. Effective E-Learning Design. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching. 2008. Available online: https://jolt.merlot.org/vol4no4/steen_1208.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Aparicio, M.; Bacao, F.; Oliveira, T. An e-Learning Theoretical Framework. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2016, 19, 292–307. [Google Scholar]

- Alharthi, A.D.; Spichkova, M.; Hamilton, M. Sustainability requirements for eLearning systems: A systematic literature review and analysis. Requir. Eng. 2019, 24, 523–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Ahmad, N.; Naveed, Q.N.; Patel, A.; Abohashrh, M.; Khaleel, M.A. E-Learning Services to Achieve Sustainable Learning and Academic Performance: An Empirical Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, L.C.; Chipeta, G.T.; Chawinga, W.D. Electronic learning benefits and challenges in Malawi’s higher education: A literature review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 11201–11218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shamali, S.; Al-Shamali, A.; Alsaber, A.; Al-Kandari, A.; AlMutairi, S.; Alaya, A. Impact of Organizational Culture on Academics’ Readiness and Behavioral Intention to Implement eLearning Changes in Kuwaiti Universities during COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Seow, C.; Servage, L. Strategizing for workplace elearning some critical considerations. J. Workplace Learn. 2005, 17, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanyan, K.; Littlejohn, A.; Margaryan, A. Sustainable e-Learning: Toward a Coherent Body of Knowledge. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2013, 16, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- ONS. Characteristics of Homeworkers, Great Britain. ONS. 2023. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/characteristicsofhomeworkersgreatbritain/september2022tojanuary2023 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Statista. Public Opinion on the State of Remote Working Worldwide in 2022. Statista. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1292234/state-of-remote-work-worldwide/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- CIPD. Workplace Technology the Employee Experience. CIPD Championing Better Work and Working Lives. 2020. Available online: https://www.cipd.org/globalassets/media/knowledge/knowledge-hub/reports/workplace-technology-2_tcm18-80853.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Swain, R. Why Study Human Resource Management? Prospectus. 2022. Available online: https://www.prospects.ac.uk/about-us (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- De Alwis, A.C.; Andrlić, B.; Šostar, M. The Influence of E-HRM on Modernizing the Role of HRM Context. Economies 2022, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.N.K.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A.; Bristow, A. Chapter 4: Understanding research philosophy and approaches to theory development. In Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson Education Ltd.: Harlow, UK, 2012; p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, E.; Bryman, A.; Harley, B. Business Research Methods, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Day, R.A.; Gastel, B. How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper, 6th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Thorpe, R.; Jackson, P.R. Management Research, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Azeiteiro, U.M.; Bacelar-Nicolau, P.; Caetano, F.J.P.; Caeiro, S. Education for sustainable development through e-learning in higher education: Experiences from Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaldi, A.; Bouzidi, R.; Nader, F. Gamification of E-Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ1364495&site=ehost-live (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Theelen, H.; van Breukelen, D.H.J. The Didactic and Pedagogical Design of E-Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. The Didactic and Pedagogical Design of E-Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2022, 38, 1286–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofiadin, A.B.M. Sustainable development, e-learning and Web 3.0: A descriptive literature review. J. Inf. Commun. Ethics Soc. 2014, 12, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, K.; Khan, S.A. Effects of e-learning technologies on university librarians and libraries: A systematic literature review. Electron. Libr. 2023, 41, 528–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, S.; Ahmad, R.; Alam, M.; Akbar, A.; Chang, V. A sustainable quality assessment model for the information delivery in E-learning systems. Inf. Discov. Deliv. 2018, 46, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceesay, L.B. Learning Beyond the Brick and Mortar: Prospects, Challenges, and Bibliometric Review of E-learning Innovation. Jindal J. Bus. Res. 2021, 10, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejbri, N.; Essalmi, F.; Jemni, M.; Alyoubi, B.A. Trends in the use of affective computing in e-learning environments. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 3867–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsabedze, V.; Ngoepe, M. A framework for quality assurance for archives and records management education in an open distance e-learning environment in Eswatini. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2021, 38, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araka, E.; Maina, E.; Gitonga, R.; Oboko, R. Research Trends in Measurement and Intervention Tools for Self-Regulated Learning for E-Learning Environments—Systematic Review (2008–2018). Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2020, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawafak, R.M.; Romli, A.B.; Alsinani, M. E-Learning System of UCOM for Improving Student Assessment Feedback in Oman Higher Education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 24, 1311–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samarraie, H.; Teng, B.K.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Alalwan, N. E-Learning Continuance Satisfaction in Higher Education: A Unified Perspective from Instructors and Students. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 2003–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.Y.; Donnelly, C.; Woods, J.; Shulha, L. Examining the Role of e-Learning in Assessment Education for Preservice Teacher Education: Challenges, Potentials, and Opportunities. Assess. Matters 2016, 10, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangrà, A.; Vlachopoulos, D.; Cabrera, N. Building an Inclusive Definition of E-Learning: An Approach to the Conceptual Framework. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2012, 13, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guri-Rosenblit, S. ‘Distance education’ and ‘e-learning’: Not the same thing. High. Educ. 2005, 49, 467–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Times. What Is E-Learning? Economic Times. 2023. Available online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/definition/e-learning (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Cambridge Dictionary. 2023. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/e-learning (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Cromier, D. 10 Things I Might Think about Using AI for in Teaching. Davecromier.blog. 2023. Available online: http://davecormier.com/edblog/ (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Cleveland-Innes, M.; Gauvreau, S.; Richardson, G.; Mishra, S.; Ostashewski, N. Technology enabled learning and the benefits and challenges of using the community of inquiry theoretical framework. Int. J. E-Learn. Distance Educ. 2019, 34, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R. Teaching-Learning and New Technologies in Higher Education: An Introduction. In Teaching Learning and New Technologies in Higher Education; Varghese, N.V., Mandal, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.; Pride, M.; Edwards, C.; Rob, T. Challenges and opportunities in co-creating a wellbeing toolkit in a distance learning environment: A case study. J. Educ. Innov. Partnersh. Change 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, S. Generative AI and Future Education. UNESCO. 2023. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000385877 (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- BBC. Chaptgpt. 2023. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-66196223 (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- CIPD. Chatgpt. 2023. Available online: https://www.cipd.org/uk/views-and-insights/thought-leadership/insight/ai-chatbots/ (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Dzyuba, N.; Jandu, J.; Yates, J.; Kushnerev, E. Virtual and augmented reality in dental education: The good, the bad and the better. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andujar, J.M.; Mejias, A.; Marquez, M.A. Augmented Reality for the Improvement of Remote Laboratories: An Augmented Remote Laboratory. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2011, 54, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCotter, S. Relocating the HR Department to the Lecture Room Using Blackboard’s Collaborate Ultra Platform: An Undergraduate and Postgraduate HR Assessment Perspective, during the COVID Pandemic. In Proceedings of the Professional Development Workshop—BAM Conference, Online, 28 June–2 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- NHS. Mental Wellbeing While Staying at Home. 2023. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/oneyou/every-mind-matters/coronavirus-COVID-19-staying-at-home-tips/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- McAlister, A. Creating Presence with Synchronous and Asynchronous Teaching. 2020. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ytlA6GfIieo&t=376s (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Yawson, D.E.; Yamoah, F.A. Understanding satisfaction essentials of E-learning in higher education: A multi-generational cohort perspective. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannion, G. Intergenerational Education and Learning: We Are in a New Place. In Families, Intergenerationality, and Peer Group Relations: Geographies of Children and Young People; Punch, S., Vanderbeck, R., Skelton, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2016; Volume 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Mohd Noor, A.S.; Alwan, A.A.; Gulzar, Y.; Khan, W.Z.; Reegu, F.A. e-learning Acceptance and Adoption Challenges in Higher Education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, H.; Burgess, G. Digital exclusion and poverty in the UK: How structural inequality shapes experiences of getting online. Digit. Geogr. Soc. 2022, 3, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.; Cotten, S.R.; Ono, H.; Quan-Haase, A.; Mesch, G.; Chen, W.; Schulz, J.; Hale, T.M.; Stern, M.J. Digital inequalities and why they matter. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2015, 18, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I. The dimensions of e-learning quality, from the learners’ perspective. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2011, 59, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIPD. Evidenced Based Learning and Development. One Size Does Not Fit All. Or Can It? CIPD Podcast Episode 184. 2023. Available online: https://www.cipd.org/uk/knowledge/podcasts/inclusive-accessible-learning/ (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Timbi-Sisalima, C.; Sánchez-Gordón, M.; Hilera-Gonzalez, J.R.; Otón-Tortosa, S. Quality Assurance in E-Learning: A Proposal from Accessibility to Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIPD. Hybrid Working: Guidance for People Professionals. CIPD. 2022. Available online: https://www.cipd.org/uk/knowledge/guides/planning-hybrid-working/ (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Jones, E.; Samra, R.; Lucassen, M. Key challenges and opportunities around wellbeing for distance learning students: The online law school experience. Open Learn. J. Open Distance e-Learn. 2021, 38, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Arimi, A.M.A. Distance Learning. Procedia Sci. Behav. Sci. 2014, 152, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasevic, D.; Kovanovic, V.; Joksimovic, S.; Siemens, G. Where is research on massive open online courses headed? A data analysis of the MOOC Research Initiative. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2014, 15, 5. Available online: http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1954/3099 (accessed on 31 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Garrison, R.; Anderson, T.; Archer, W. From Critical inquiry in text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2016, 2, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Cela, K.L.; Sicilia, M.Á.; Sánchez, S. Social Network Analysis in E-Learning Environments: A Preliminary Systematic Review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 27, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.L.; Camille Dickson-Deane, C.; Galyen, K. e-Learning, online learning, and distance learning environments: Are they the same? Internet High. Educ. 2011, 14, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disterer, G.; Kliener, C. BYOD. Bring your Own Device. Procedia Technol. 2013, 9, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaurav, R.P.S.; Rajput, S.; Baber, R. Factors Affecting the Acceptance of E-learning By Students: A Study of E-learning Programs in Gwalior, India. South Asian J. Manag. 2019, 26, 76–95. [Google Scholar]

- Perales Jarillo, M.; Pedraza, L.; Moreno Ger, P.; Bocos, E. Challenges of Online Higher Education in the Face of the Sustainability Objectives of the United Nations: Carbon Footprint, Accessibility and Social Inclusion. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahel, O.; Lingenau, K. Opportunities and Challenges of Digitalization to Improve Access to Education for Sustainable Development in Higher Education. In Universities as Living Labs for Sustainable Development: Supporting the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals; World Sustainability Series; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 341–356. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry, A. Legal and Practical Tips for Employers on Home Working. 2020. Available online: https://www.personneltoday.com/hr/legal-practical-tips-employers-homeworking/ (accessed on 7 May 2020).

- ACAS. Working From Home. 2020. Available online: https://www.acas.org.uk/working-from-home (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Mental Health at Work, Coronavirus—Supporting Yourself and Your Team. 2020. Available online: https://www.mentalhealthatwork.org.uk/resource/coronavirus-supporting-yourself-and-your-team/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- UNICEF. Rethinking Screen-Time in the Time of COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/stories/rethinking-screen-time-time-COVID-19 (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Michinov, N.; Brunot, S.; Le Bohec, O.; Juhel, J.; Delaval, M. Procrastination, participation, and performance in online learning environments. Comput. Educ. 2011, 56, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Previous SLRs | Key Themes | Shortcomings |

|---|---|---|

| Ref. [4] | Definition of e-learning | Not specific to HR |

| Identification of common myths | Pre-COVID-19 | |

| Review of research over a decade Identification of the most common theories and modalities | ||

| Ref. [6] | Sustainability meta-requirements | Pre-COVID-19 |

| e-learning systems | Engineering Focus | |

| e-learning sustainability checklist | Timeline 2005–2017 | |

| Greenability Not HR-specific | ||

| Ref. [7] | e-learning service framework Sustainability via systems COVID-19 as a global driver | Not specific to HR Range of E-learner users examined is too broad |

| Ref. [8] | A range of quality determinants Range of e-learning models 4-dimensional conceptual model | |

| International dimensions Academic context Institutional responsibilities Key stakeholders | Range of terms Not HR-specific |

| Previous SLRs | Key Themes | Shortcomings |

|---|---|---|

| Ref. [9] | Higher Education | Country-Specific |

| Academic Business Discipline | Private/Public HE | |

| Change Management | ||

| Ref. [10] | Industry-Focused | Lacks Jrnl. Articles |

| Grey Literature | Data | |

| Ref. [11] | Concept of Sustainability | Pre-COVID-19 |

| Origins of Sustainability | Broad Spectrum | |

| Educational Context | Search Strings | |

| Education Attainment Resource Management Professional Development |

| Item | Descriptor |

|---|---|

| Review of Methodology | Protocol |

| Preliminary Literature Search | |

| Scoping Review | |

| - Eligibility Criteria | |

| - Information Sources | |

| - Search Terms | |

| Selection of sources of evidence | |

| Prisma Flow Chart | |

| Data Charting Process (Preliminary Search)—Categories and Units | |

| Data Charting Process (Scoping Review)—Categories and Units | |

| - Data Items | |

| Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence | |

| Synthesis of Results | |

| Results | Selection of Sources of Evidence |

| Characteristics of Sources of Evidence - Percentage of Publications by database - Percentage of Articles Review by database - Themes—Preliminary Search - Themes—Scoping Review | |

| Critical Appraisal Within Sources of Evidence | |

| Results of Individual Sources of Evidence | |

| Discussion - Preliminary Search - Scoping Review | |

| Discussions | Summary of Evidence |

| Limitations | |

| Conclusions | |

| Future Directions | |

| Funding | Funding |

| Review Title and Timescales | ||

|---|---|---|

| Review Title: | Sustaining e-learning: the current landscape and future direction within Human Resources Higher Education. An interdisciplinary scoping review | |

| Start Date | April 2023 | |

| Anticipated Completion Date | TBC as article is still under review | |

| Stage of Review at the Time of this Submission | Preliminary searches: | COMPLETED |

| Search results: | COMPLETED | |

| Formal screening via eligibility criteria: | COMPLETED | |

| Data extraction: | COMPLETED | |

| Risk bias (quality) assessment: | COMPLETED | |

| Data analysis: | COMPLETED | |

| Preliminary Search | HR and e-learning; defining e-learning/e-learning and higher education; technology-enabled e-learning; new technologies and e-learning; BYOD; distance learning; generational e-learning; virtual and augmented reality; online assessment; online presence; digital exclusion; challenges and e-learning; defining e-learning/e-learning and the economy/desituated learning; accessible e-learning; working from home; screen time; sustainable e-learning design | |

| Inclusion Criteria | Adults/students/employees over 18 | |

| Exclusion Criteria | Primary/secondary-level education; COVID-19 commissioned study | |

| Screening of search results | Completed | |

| Risk of Bias Statement | Not applicable | |

| Data Analysis | Completed | |

| Reviewer Details | ||

| Reviewer Contact Details: | As per the author’s contact details for this article | |

| Affiliated HE Institution: | As per the author’s employer HEI details for this article | |

| Funding Sources: | No funding has been sought for this work nor has this work been commissioned | |

| Conflict of Interests | The author has no conflicts of interest to declare | |

| Review Methods | ||

| Review Question: | What is known about sustainable e-learning Human Resource higher education provision within the literature in terms of themes, benefits, challenges, and future directions? | |

| Literature Search | A preliminary search was undertaken using the most common business databases available within the library catalogue of the author’s employing university. This included Business Source Premier and JSTOR. Grey literature was also considered in this preliminary search and was sourced from a wide range of HR/business sources, which can be more difficult to identify, e.g., CIPD.org.uk; IATED.org/ICERi/; Google Scholar; and MERLOT. Following analysis of the preliminary search results, the more extensive scoping literature review was undertaken using EBESCO (including Business Source Premier and ERIC), Emerald, and Science Direct. Some more specific HR journals were also considered including the Journal of Human Resource Management and the International Journal of Human Resource Management. | |

| Domain Being Studied | The scoping review seeks to examine the extent to which research into sustainable e-learning in Human Resources higher education is being undertaken and the related contexts, benefits, challenges, and future directions. | |

| Participants/Population | This work is concerned with studies/SLR/scoping reviews focused upon e-learning among adults within an HR HEI and/or employment context. | |

| Interventions/Exposure | Not applicable as this scoping review is primarily concerned with peer-reviewed articles and grey literature involving business reports/scholarly articles. No social media, blogs, and/or video blogs are being used in this scoping review. | |

| Comparator/Controls | Any comparator is relevant for inclusion including higher-education-institute-related studies whether specific to Human Resource education provision or other business/education-specific provision. Also, this applies to any comparator study focusing upon sustainable e-learning among adults/students over 18 years of age, irrespective of context. | |

| Types of Study to be Included Initially | All types of publications are to be included, e.g, published articles, articles in conference proceedings, editorial websites, chapters in textbooks, and business reports. | |

| Context | All periods of time are eligible—excluding studies with a major focus on COVID-19-related sustainable e-learning. | |

| Primary Outcomes | The broad categories of outcomes anticipated within this study include the following: the extent to which research into sustainable e-learning HRHE is being undertaken within the field of HR and/or business-related disciplines. It is anticipated that there is a lack of such research, and as such, it is expected reliance will need to be placed upon an interdisciplinary body of work as it related to sustainable e-learning within a range of business and education disciplines as well as sustainable e-learning within organisations. | |

| Secondary Outcomes | Not applicable. | |

| Data Extraction (Selection and Coding) | As there is no one standard/agreed approach to analysing qualitative data in Ref. [17], a generic approach to analysis will be applied within the PRISMA-ScR protocol. This generic analysis will allow for a structured approach to the categorisation of themes. It is considered this will lend itself to the deductive nature of this study, given the use of existing secondary data/articles/reports, etc. [17,19]. As this is a scoping review and not an SLR/meta-analysis, data extraction has not relied on software and instead upon a thematic analysis of articles, using document summaries [17,19]. The extraction will draw upon the 5 principles put forward in Ref. [17], which are as follows: 1. Comprehend large and disparate forms of qualitative data; 2. Integrate related data from different texts and notes; 3. Identify key themes and patterns for further exploration; 4. Develop theories based upon these patterns and themes; 5. Draw conclusions. Following these guiding principles and building upon the work of Miles and Huberman (1994) [20] regarding “data reduction”, the following interim steps are applied: The first step will be identification of categories arising from the literature—attach meaning to each category by applying a “name”—formally referred to as a “code” or “label”. Each code/label provides the initial “structure” of the data extraction. The identification of the categories will be dictated by the research question and objectives. As such, this keeps with the philosophical positioning of this study. As this is a scoping review, categories will be “concept driven” from the literature, e.g., from theory within the literature as recommended in Ref. [17]. As the categories (codes/labels) are added, a well-structured analytical framework develops. This analytical framework then aids the analysis of the data extraction stage. According to the author of Ref. [21], categories require two dimensions—they must be (a) meaningful to the data from which they were generated and (b) be meaningful to the other categories. Next step: Units To aid the extraction, each category needs to have a “unit” of data attached to it. As this is a scoping review, units can be words/phrases or abbreviations from the literature but must relate to the categories. Categories and units can be placed in the margins of extracts from the literature or placed in a separate document with details of the page number/line number to which they relate in each piece of the literature, in Ref. [22]. For the purposes of transparency and to minimise bias, extracts of both approaches are made available within this study. This results in data being presented in a more useful and manageable way [17]. | |

| Strategy for Data Synthesis | Following the establishment of categories and units, a vertical hierarchical data extraction table will be used to illustrate the categories and units against each study. This is intended to aid the reporting of data for this ScR. | |

| Analysis of Sub-groups or Sub-sets | Not applicable. | |

| Risk of Bias (Quality Assessment) | It is acknowledged this scoping review is being undertaken by one author only, which can lead to subjective bias. However, care is being taken to minimise such bias through the use of the PRISMA-ScR protocol to aid transparency. As this is a scoping review and not a systematic literature review, the point is raised that any future development of this study will consider inclusion of more than one reviewer to minimise bias further. | |

| Type of Review—Select One of the Following: • Scoping Review • SLR • Rapid Review • Other | Scoping Review. | |

| Language | English | |

| Country | UK and International | |

| URL for Publication of Protocol | No URL: Author’s email address—protocol provided on request | |

| Dissemination Plans | If this study passes the review stage, it is hoped that approval will be given for publication in the MDPI Journal Special Issue—Sustainable E-Learning Practices. | |

| Key Words | e-learning; sustainable e-learning; tertiary education and e-learning; e-learning quality assurance; AI and e-learning; university support for e-learning; e-learning and student perceptions; online learning; digital learning; desituated e-learning | |

| Details of Other Existing Protocols on the Same Topic by the Same Author | None/not applicable | |

| Current Review Status | Ongoing | |

| Any Additional Information | Not applicable | |

| Details of Final Report/Publication | Not applicable—review still in progress. | |

| Period of Searches | Databases and Search Terms | No. of Results |

|---|---|---|

| June–August 2023 | Business Source Premier | 3 |

| JSTOR | 28 | |

| Search terms: HR and e-learning; defining e-learning/e-learning and higher education; technology-enabled e-learning; new technologies and e-learning; BYOD; distance learning; generational e-learning; virtual and augmented reality; online assessment; online presence; digital exclusion; challenges and e-learning |

| Period of Searches | Grey Literature and Search Terms | No. of Results |

|---|---|---|

| June–August 2023 | CIPD: sustainable e-learning | ChatGPT 3 |

| AI: evidenced-based learning | hybrid working | |

| Google Scholar: | ||

| Defining e-learning/e-learning and the economy/desituated learning; accessible e-learning; working from home; screen time | 9 | |

| MERLOT: sustainable e-learning design | 1 |

| Search Terms: Preliminary Search Databases | |

|---|---|

| 1 | HR and e-learning |

| 2 | Defining e-learning |

| 3 | e-learning and higher education |

| 4 | Technology enabled e-learning |

| 5 | New technologies and e-learning |

| 6 | Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) |

| 7 | Distance learning |

| 8 | Generational e-learning |

| 9 | Virtual and augmented reality |

| 10 | Online assessment |

| 11 | Online presence |

| 12 | Digital exclusion |

| 13 | Challenges and e-learning |

| Search Items: Preliminary Search Grey Literature | |

|---|---|

| 1 | E-learning and the economy |

| 2 | Desituated learning |

| 3 | Accessible e-learning |

| 4 | Working from home |

| 5 | Screen time |

| Date Range | Search Terms | Database |

|---|---|---|

| August 2023 | Content, type, article: sustainable e-learning | Business Source Premier |

| August 2023 | e-learning and systematic lit review and higher education | (EBESCO) ERIC |

| August 2023 | (content-type: article) e-learning systematic review | Emerald |

| August 2023 | (content-type: article) AND (title: “e-learning” AND (title: “sustainable”) AND (abstract: “systematic literature review”)) | Emerald |

| August 2023 | (content-type: article) AND (title: “higher education” AND (title: “e-learning”) AND (abstract: “systematic review”)) | Emerald |

| August 2023 | (content-type: article) AND (title: “Human Resource” AND (title: “e-learning”) AND (title: “systematic literature review”)) | Emerald |

| August 2023 | (content-type: article) AND (title: “Human Resource” AND (title: “E-learning”) AND (title: “sustainable”) AND (title: “Education”)) | Emerald |

| August 2023 | (content-type: article) AND (title: “Human Resources” AND (title: “Higher Education”) AND (title: “e-learning”) AND (abstract: “sustainable”)) | Emerald |

| August 2023 | e-learning (TI) sustainable (Ab Abstract); Higher education (Ab Abstract Abs); systematic review (TI) | EBESCO Host Business Source Premier—Human Resource Management Journal |

| August 2023 | e-learning (TI) systematic review (TI) | EBESCO Host Business Source Premier—Int Journal of Human Resource Management J |

| August 2023 | e-learning (TI) systematic literature review (AB Abstract) | EBESCO Business Source Premier and ERIC databases |

| August 2023 | e-learning (TI) systematic literature review (AB Abstract) | MDPI SLRs |

| August 2023 | e-learning (TI) systematic literature review (AB Abstract) | Science Direct |

| Themes/Category | Unit | Sub-Category | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terminology | Term | Distance learning Remote learning Online learning e-learning Procedural Construct | Term-DL Term-RL Term-OL Term-EL Term-Proc Term-Const |

| Technology | Tech | Access, equity, space, quality assurance, economic/socio-demographics User expectations Complexity Bring Your Own Device Place and place settings Interdisciplinary—art and design Systems Infrastructure Screen time | Tech-Access Tech-Equity Tech-space Tech-qual-assur Tech-econ Tech-sociodem Tech-user-Expec Tech-compl Tech-BYOD Tech-place-sett Tech-Interdisc-Art-des Tech-Infa Tech-Scr-T |

| e-learning | EL | Space and presence Platforms Practice mirroring Materials Desituated space Synchronous/a-synchronous Access Equity and fairness Generational International perspectives QA | EL-space EL-pres EL-platf EL-Pract-mirr EL-mater EL-Desitu-Spc EL-Sync EL-A-Sync EL-Acc EL-Equ-Fair EL-Gen EL-Int-Persp EL-QA EL-Int-persp EL-QA |

| Artificial Intelligence | AI | Artificial Intelligence Augmented reality Virtual reality ChatGPT HE sector Student confidentiality Ethics Staff proficiency Procurement Algorithm accountability Teaching possibilities Platforms | AI-AI AI-Aug-R AI-V-R AI-Chat AI-HE-Sec AI-Stud-confi AI-Ethics EI-Staff-Prof AI-Proc AI-Algor AI-Acc AI-Teach-Poss AI-Plat |

| Institutional Responsibilities | IntsR | Contractual—staff and student Place of work Place of study Remote work/study Wellbeing | InstR-Cont-Staff InstR-Cont-Stud InstR-Pl-o-Wk InstR-Pl-o-Std InstR-WellB |

| Themes/Category | Label | Sub-Category | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| HE students—undergraduate, postgraduate, and Ph.D. | HE-S-UG-PG-PhD | In full-time employment Part-time study Learning quality Structure and organisation of Materials Communication tools Teaching expertise Motivating skills, Learning e-activities Societal impact | HE-S-FT-E HE-S-PT-S LQ HE-S-Materials-HE-S-Struct-Org HE-S-Comms-tools HE-S-T-E HE-S-Mot-S HE-S-Learn-E-Act HE-S-Soct-Impt |

| E-learning and gamification | E-L-GameF | Intergenerational Design principles Individual tailoring | EL-GameF-Inter-G Des-P Ind-Tayl |

| Pedagogical design of e-learning | EL-Ped-Des | Content and process scaffolding Learner adaptability | EL-GameF-Cont-Scaf Proc-Scaft L-Adap |

| Principle-based e-learning | Princ-B-E-L | Gamification and motivation Block-chain technology Parameters Resources Infrastructure | Princ-B-E-L-GamF-Motv Bloc-C-Tech Param Res Infa-S |

| Sustainable e-learning benefits | Sust-E-L-Ben | Assessment quality | Sust-E-L-Ben-Assmt-Q |

| e-learning content | E-L-Cont | Learning experiences Appropriate platforms Feedback Instructor–student communication | E-L-Cont-L-Exp App-Plat Feed-B Inst-Stu-Comms |

| e-learning as an evolution of distance learning | E-L-Ev-Dist-L | Affective computing Intelligent tutoring systems Emotional intelligence | E-L-Ev-Dist-L-Aff-Compt I-T-S E-I |

| e-learning quality assurance Framework | E-L-Qual-Ass-F | Cost effectiveness Distance learning component Quality assurance criteria | E-L-Qual-Ass-F-C-E D-L-C Qual-Ass-C |

| e-learning measurement and intervention tools | E-L-M E-L-I | Self-directed learning Challenges | E-L-M-I-S-D-L Chall |

| Platforms and e-learning assessments | PlatF-E-L-LA | Student satisfaction Senior faculty responsibility | PlatF-E-L-LA Stud-Satf Snr Fac-R |

| e-learning assessments | E-L-A | Assessment administration Assessment design | E-L-A-A-Admin A-D |

| e-learning theories | E-L-Th | Community of inquiry Technological acceptance model | E-L-Th-Comm-Inq Tech-Acc-M |

| e-learning study and employment | E-L-Stdy-Empl | Viable alternative to in-person teaching | E-L-Stdy-Empl-V-A-In-Pers-T |

| Date | Search Terms | Database | No. of Articles | Excluded | Included | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| August 2023 | Content, type, article: sustainable e-learning | Business Source Premier | 2 | 1 (mentioned COVID) | 1 | Ref. [20] | |

| August 2023 | e-learning and systematic lit review and higher education | (EBESCO) ERIC | 2 | 0 | 2 | Ref. [24] | |

| August 2023 | Ref. [25] | ||||||

| Emerald | 3 | 1 | 2 | One article excluded as SLR/SR not mentioned in title nor abstract | Ref. [26] | ||

| 2nd article not accessible | |||||||

| August 2023 | (content-type: article) e-learning systematic review | Emerald | 2 | 1 | 1 | Ref. [27] | |

| August 2023 | (content-type: article) AND (title: “e-learning” AND (title: “sustainable”) AND (abstract: “systematic literature review”)) | Emerald | 1 | 0 | 1 | Ref. [28] | |

| August 2023 | (content-type: article) AND (title: “higher education” AND (title: “e-learning”) AND (abstract: “systematic revie | Emerald | 1 | 1 (as SLR quoted not applied to the article) | 0 | N/A | |

| August 2023 | (content-type: article) AND (title: “Human Resource” AND (title: “e-learning”) AND (title: “systematic literature review”)) | Emerald | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| August 2023 | (content-type: article) AND (title: “Human Resource” AND (title: “E-learning”) AND (title: “sustainable”) AND (title: “Education”)) | Emerald | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| August 2023 | (content-type: article) AND (title: “Human Resources” AND (title: “Higher Education”) AND (title: “e-learning”) AND (abstract: “sustainable”)) | Emerald | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| August 2023 | e-learning (TI) sustainable (Ab Abstract); Higher education (Ab Abstract Abs); systematic review (TI) | EBESCO Host Business Source Premier—Human Resource Management Journal | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| August 2023 | e-learning (TI) systematic review (TI) | EBESCO Host Business Source Premier—Int Journal of Human Resource Management J | 2 | 1 (case-study-specific, not SLR) | 1 | Ref. [29] | |

| August 2023 | e-learning (TI) systematic literature review (AB Abstract) | EBESCO Business Source Premier and ERIC databases | 13 | 7 | 5, e.g., 1 (as K-12 children specific); 1 as case study and not purely SLR; 1 as COVID-19 specific; 1 duplicate article already included in this SLR; 1 was a conference proceeding review. | Ref. [30] | |

| August 2023 | Duplication | Ref. [24] | |||||

| August 2023 | Ref. [31] | ||||||

| August 2023 | Ref. [32] | ||||||

| August 2023 | Ref. [33] | ||||||

| August 2023 | Ref. [34] | ||||||

| August 2023 | Uses “general lit review not a SLR” Ref. [35] | ||||||

| August 2023 | Ref. [36] | ||||||

| August 2023 | MDPI SLRs | Ref. [4] | |||||

| August 2023 | Science Direct | Ref. [20] |

| Themes/Category | Label | Sub-Category | Code | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terminology | Term | Distance learning Remote learning Online learning e-learning Procedural Construct | Term-DL Term-RL Term-OL Term-EL Term-Proc Term-Const | Refs. [5,25,37,38,39,40,41,42] |

| Technology | Tech | Access, equity, space, quality assurance, economic/socio-demographics User expectations Complexity Bring Your Own Device Place and place settings Interdisciplinary—art and design Systems Infrastructure Screen time | Tech-Access Tech-Equity Tech-space Tech-qual-assur Tech-econ Tech-sociodem Tech-user-Expec Tech-compl Tech-BYOD Tech-place-sett Tech-Interdisc-Art-des Tech-Infa Tech-Scr-T | Refs. [2,25,40,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] |

| e-learning | EL | Space and presence Platforms Practice mirroring Materials Desituated space Synchronous/a-synchronous access Equity and fairness Generational International perspectives QA | EL-space EL-pres EL-platf EL-Pract-mirr EL-mater EL-Desitu-Spc EL-Sync EL-A-Sync EL-Acc EL-Equ-Fair EL-Gen EL-Int-Persp EL-QA EL-Int-persp EL-QA | Refs. [2,42,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60] |

| Artificial Intelligence | AI | Artificial Intelligence Augmented reality Virtual reality ChatGPT HE sector Student confidentiality Ethics Staff proficiency Procurement Algorithm accountability Teaching possibilities Platforms | AI-AI AI-Aug-R AI-V-R AI-Chat AI-HE-Sec AI-Stud-confi AI-Ethics EI-Staff-Prof AI-Proc AI-Algor AI-Acc AI-Teach-Poss AI-Plat | Refs. [44,45,46,47,48,49,50] |

| Institutional Responsibilities | IntsR | Contractual—staff and student Place of work Place of study Remote work/study Wellbeing | InstR-Cont-Staff InstR-Cont-Stud InstR-Pl-o-Wk InstR-Pl-o-Std InstR-WellB | Refs. [42,44,51,61,62,63,64,65] |

| Themes/Category | Label | Sub-Category | Code | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HE students—undergraduate, postgraduate, and Ph.D. | HE-S-UG-PG-PhD | In full-time employment Part-time study Learning quality Structure and organisation of materials Communication tools Teaching expertise Motivating skills, learning e-activities Societal impact | HE-S-FT-E HE-S-PT-S LQ HE-S-Materials-HE-S-Struct-Org HE-S-Comms-tools HE-S-T-E HE-S-Mot-S HE-S-Learn—E-Act HE-S-Soct-Impt | Ref. [20] |

| E-learning and gamification | E-L-GameF | Intergenerational Design principles Individual tailoring | EL-GameF-Inter-G Des-P Ind-Tayl | Ref. [66] |

| Pedagogical design of e-learning | EL-Ped-Des | Content and process scaffolding Learner adaptability | EL-GameF-Cont-Scaf Proc-Scaft L-Adap | Ref. [25] |

| Principle-based e-learning | Princ-B-E-L | Gamification and motivation Block-chain technology Parameters Resources Infrastructure | Princ-B-E-L-GamF-Motv Bloc-C-Tech Param Res Infa-S | Ref. [26] |

| Sustainable e-learning benefits | Sust-E-L-Ben | Assessment Quality | Sust-E-L-Ben-Assmt-Q | Ref. [28] |

| e-learning content | E-L-Cont | Learning experiences Appropriate platforms Feedback Instructor–student communication | E-L-Cont-L-Exp App-Plat Feed-b Inst-Stu-Comms | Ref. [29] |

| e-learning as an evolution of distance learning | E-L-Ev-Dist-L | Affective computing Intelligent tutoring systems Emotional intelligence | E-L-Ev-Dist-L-Aff-Compt I-T-S E-I | Ref. [30] |

| e-learning quality assurance framework | E-L-Qual-Ass-F | Cost effectiveness Distance learning component Quality assurance criteria | E-L-Qual-Ass-F-C-E D-L-C Qual-Ass-C | Ref. [31]. |

| e-learning measurement and intervention tools | E-L-M E-L-I | Self-directed learning Challenges | E-L-M-S-D-L Chall | Ref. [32] |

| Platforms and e-learning assessments | PlatF-E-L-LA | Student satisfaction Senior faculty responsibility | PlatF-E-L-LA Stud-Satf Snr Fac-R | Ref. [33] |

| e-learning assessments | E-L-A | Assessment administration Assessment design | E-L-A-A-Admin A-D | Ref. [35] |

| e-learning theories | E-L-Th | Community of inquiry Technological acceptance model | E-L-Th-Comm-Inq Tech-Acc-M | Ref. [4] |

| e-learning study and employment | E-L-Stdy-Empl | Viable alternative to in-person teaching | E-L-Stdy-Empl-V-A-In-Pers-T | Ref. [20] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCotter, S. An Interdisciplinary Scoping Review of Sustainable E-Learning within Human Resources Higher Education Provision. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15282. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115282

McCotter S. An Interdisciplinary Scoping Review of Sustainable E-Learning within Human Resources Higher Education Provision. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15282. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115282

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCotter, Sinéad. 2023. "An Interdisciplinary Scoping Review of Sustainable E-Learning within Human Resources Higher Education Provision" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15282. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115282