Implementation of Biosphere Reserves in Poland–Problems of the Polish Law and Nature Legacy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Is a biosphere reserve in Poland a functional structure noted in Polish legal, planning, and strategic documents?

- Is a biosphere reserve in Poland a tool for nature protection?

- Does the existence of a biosphere reserve have an impact on local development by supporting social initiatives?

- Are promotional and educational activities and scientific research carried out in biosphere reserves, in accordance with local and national sustainable development programs? If so, what are they about, are they long-term and systematic, or ad hoc and individual?

- Is cross-border cooperation sufficient? Are there legal and financial mechanisms to support such cooperation in Poland?

- Legal regulations (conventions, international agreements, laws, and regulations)

- Strategic documents related to state policy on environmental protection and natural resource management as well as regional policy

- Planning documents at the national, regional, and local levels

- Nature protection plans for national parks, landscape parks, and nature reserves

- Protective plans for NATURA 2000 areas

- Economic-protective programs for forest promotional complexes

- Forest management plans for forest districts

- Audit reports conducted by the Supreme Audit Office

3. Results

3.1. The Results of Analysis of National Legal Acts—BRs as a Tool for Legal Protection of Nature in Poland

3.2. Results of National (Polish) Strategic Analyses—The Impact of BRs on Local Development and Social Initiatives

3.2.1. National Strategic and Planning Documents

3.2.2. Regional and Local Strategic and Planning Documents

3.2.3. Plans for Protecting Nature Forms Including BRs

3.2.4. Economic Documents of Forest Area Managers Covered by BRs

3.3. Results of the Analysis of Documents Evaluating the Functioning of Biosphere Reserves

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Polish biosphere reserves are not established in Polish legislation and contrary to UNESCO recommendations, cannot be subject to it. For over 45 years, since the first BR was adopted in Poland, there have not been legal forms of nature protection. They have not contributed to increased conservation and sustainable development efforts in the country, whatever that might mean. The idea of sustainable functioning of nature and humans is generally either little known or completely alien.

- The significance of BRs in Polish political and socio-economic realities is only declarative. Generally, biosphere reserves do not have a translation into strategically planned socio-economic development, expressed by development documents (development strategies, planning, and spatial development documents). Valuable natural areas, including forms of nature protection and protected areas based on ratified international conventions and other international agreements (e.g., UNESCO), despite the role and function they should play in nature and landscape protection, lose out to investment and settlement pressure that guarantees profits.

- Biosphere reserves in Poland do not function according to the assumptions of the Man and the Biosphere Program and are not model examples of protected areas implementing sustainable development principles. The assessment carried out shows that the real functioning of biosphere reserves in Poland is very doubtful.

- Revision of national legislation is absolutely necessary to provide a clear legal framework for biosphere reserves as forms of nature protection with defined tasks. Polish biosphere reserves are an untapped research field for sustainable development, ecosystem services, and experiences related to social and economic relationships between humans and the environment. It is necessary, in cooperation with scientific, social, and local government communities involved in local spatial policies, to develop an action program for nature reserves in Poland. This should be a strategic program, until 2040, and shorter operational programs, covering sequences of 5 years each.

- The Polish side does not have the legal and financial instruments to develop transboundary cooperation on biosphere reserves. In the current situation, cross-border cooperation with Ukraine is currently very limited (war). With the existing Schengen border protection system separating the Ukrainian part from the Polish and Slovak parts, the coordinating council of the Eastern Carpathian Transboundary Biosphere Reserve is not able to meet the requirements for a coordinating body in the Pamplona Recommendations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Man and Biosphere; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- The Madrid Action Plan for Biosphere Reserves (2008–2013) from the 3rd World Congress of Biosphere Reserves held in Madrid in 2008. Gombierno de Espana, Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000163301 (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- The Lima Action Plan for UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme and Its World Network of Biosphere Reserves (2016–2025). Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/SC/pdf/Lima_Action_Plan_en_final.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- The Seville Strategy for Biosphere Reserves 1996 from the International Conference on Biosphere Reserves, Final Report, Annex 5. UNESCO, MAB Report Series, No. 65. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0010/001035/103544e.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Fiske, D. Towards an Anthropocene Narrative and a New Philosophy of Governance: Evolution of Global Environmental Discourse in the Man and the Biosphere Programme. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2022, 24, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa z dnia 7 kwietnia 1949 r. o ochronie przyrody. [Act of April 7, 1949 on the protection of nature]. J. Laws 1949, 25, 180.

- Ustawa z dnia 16 października 1991 r. o ochronie przyrody. [Act of October 16, 1991, on the protection of nature]. J. Laws 1991, 114, 492.

- Ustawa z dnia 16 kwietnia 2004 r. o ochronie przyrody. [Act of April 16, 2004, on the protection of nature]. J. Laws 2004, 92, 880.

- Bird Directive: Council Directive 79/409/EEC of April 2, 1979 on the Conservation of Wild Birds. Off. J. Eur. Union 1979, 103, 1–18.

- Habitat Directive: Council Directive 92/43/EEC of May 21, 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. Off. J. Eur. Union 1992, 206, 50.

- Uchwała nr 102 Rady Ministrów z dnia 17 września 2019 r. w sprawie przyjęcia “Krajowej Strategii Rozwoju Regionalnego 2030”. [Resolution No. 102 of the Council of Ministers of September 17, 2019, on the adoption of the “National Regional Development Strategy 2030”]. J. Laws 2019, 1060.

- Uchwała nr 67 Rady Ministrów z dnia 16 lipca 2019 r. w sprawie przyjęcia “Polityki ekologicznej państwa 2030—Strategii rozwoju w obszarze środowiska i gospodarki wodnej”. [Resolution No. 67 of the Council of Ministers of July 16, 2019, on the adoption of the “Ecological Policy of the State 2030—Development strategy in the field of the environment and water economy”]. J. Laws 2019, 794.

- Uchwała nr 8 Rady Ministrów z dnia 14 lutego 2017 r. w sprawie przyjęcia Strategii na rzecz Odpowiedzialnego Rozwoju do roku 2020 (z perspektywą do 2030 r.). [Resolution No. 8 of the Council of Ministers of February 14, 2017, on the adoption of the Strategy for Responsible Development until 2020 (with a perspective until 2030)]. J. Laws 2017, 260.

- Uchwała nr 213 Rady Ministrów z dnia 6 listopada 2015 r. w sprawie zatwierdzenia “Programu ochrony i zrównoważonego użytkowania różnorodności biologicznej wraz z Planem działań na lata 2015–2020”. [Resolution No. 213 of the Council of Ministers of November 6, 2015, on the approval of the “Programme for the Protection and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity along with an Action Plan for the years 2015–2020”]. J. Laws 2015, 1207.

- Uchwała Nr 239 Rady Ministrów, z dnia 13 Grudnia 2011 r., w Sprawie Przyjęcia Koncepcji Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju 2030. Załącznik: Koncepcja Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju 202030. [Resolution No. 102 of the Council of Ministers of December 13, 2011 on the Adoption Concept of Spatial Development of the Country 2030. Appendix: Concept of Spatial Development of the Country 2030]. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wmp20120000252 (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Ustawa z dnia 15 lipca 2020 r. o zmianie ustawy o zasadach prowadzenia polityki rozwoju oraz niektórych innych ustaw. [Act of July 15, 2020, amending the Act on the principles of conducting development policy and certain other acts]. J. Laws 2020, 1378.

- Uchwała 72/22 Sejmiku Województwa Mazowieckiego z Dnia 2022-05-24 w Sprawie Strategii Rozwoju Województwa Mazowieckiego 2030+. Załącznik: Strategia Rozwoju woj. Mazowieckiego do 2030. Innowacyjne Mazowsze. [Resolution No. 72/22 of the Regional Council of the Mazovian Voivodeship Dated May 24, 2022, Regarding the Development Strategy of the Mazovian Voivodeship 2030+—Appendix: Development Strategy of The Masovian Voivodeship until 2030. Innovative Mazowsze]. Available online: www.mbpr/pl (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Uchwała NR XXVII/458/20 Sejmiku Województwa Podkarpackiego z Dnia 28 Września 2020 r. w Sprawie Przyjęcia Strategii Rozwoju Województwa—Podkarpackie 2030. Załącznik: Strategia Rozwoju Województwa—Podkarpackie 2030. [Resolution No. XXVII/458/20 of the Regional Council of the Subcarpathian Voivodeship dated September 28, 2020, Regarding the Adoption of the Development Strategy of the Subcarpathian Voivodeship—Subcarpathian 2030. Appendix: Development Strategy of the Subcarpathian Voivodeship—Subcarpathian 2030]. Available online: www.podkarpackie.pl/ (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Uchwała nr XXI/422/20 Sejmiku Województwa Małopolskiego z Dnia 17 Grudnia 2020 Roku Sprawie Przyjęcia Aktualizacji Strategii Rozwoju Województwa Małopolskiego na Lata 2011–2020 pn. Strategia Rozwoju Województwa “Małopolska 2030”. Załącznik: Strategia Rozwoju Województwa Małopolskiego na Lata 2011–2020 pn. Strategia Rozwoju Województwa “Małopolska 2030. [Resolution No. XXI/422/20 of the Regional Council of the Lesser Poland Voivodeship Dated December 17, 2020, Regarding the Adoption of the Update of the Development Strategy of the Lesser Poland Voivodeship for the Years 2011–2020, Titled “Development Strategy of the Lesser Poland Voivodeship “Małopolska 2030””. Appendix: Development Strategy of the Lesser Poland Voivodeship until 2030]. Available online: www.malopolska.pl/ (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Appendix: Development Strategy of the Subcarpathian Voivodeship. In Resolution No. XVIII/213/2020 of the Regional Council of the Subcarpathian Voivodeship Dated April 27, 2020, Regarding the Adoption of the Development Strategy of the Subcarpathian Voivodeship 2030; Pomeranian Voivodeship Office: Gdansk, Poland, 2020.

- Appendix: Development Strategy of the Pomeranian Voivodeship 2030. In Resolution No. 376/XXXI/21 of the Regional Council of the Pomeranian Voivodeship Dated April 12, 2021; Pomeranian Voivodeship Office: Gdansk, Poland, 2021.

- Appendix: Development Strategy of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship 2030. In Resolution No. L/1790/18 of the Regional Council of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship Dated September 20, 2018; Pomeranian Voivodeship Office: Gdansk, Poland, 2018.

- Appendix: Warmian-Masurian 2030. Strategy of Socio-Economic Development. In Resolution No. XIV/243/20 of the Regional Council of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship Dated February 18, 2020, Regarding the Adoption of the Development Strategy of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship: “Warmian-Masurian 2030. Strategy of Socio-Economic Development”; Pomeranian Voivodeship Office: Gdansk, Poland, 2020.

- Appendix: Development Strategy of the Lubelin Voivodeship until 2030. In Resolution No. XXIV/406/2021 of the Regional Council of the Lublin Voivodeship; Pomeranian Voivodeship Office: Gdansk, Poland, 2021.

- Appendix: Development Strategy of the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship until 2030—Acceleration Strategy 2030+. In Resolution No. XXVIII/399/20 of the Regional Council of the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship Dated December 21, 2020, Regarding the Adoption of the Development Strategy of the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship until 2030—Acceleration Strategy 2030+; Pomeranian Voivodeship Office: Gdansk, Poland, 2020.

- Uchwała Nr XXXVI/330/17 Sejmiku Województwa Podlaskiego z Dnia 22 Maja 2017 r. w Sprawie Planu Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Województwa Podlaskiego. [Resolution No. XXXVI/330/17 of the Regional Council of Podlaskie Voivodship of 22 May 2017 on the Spatial Development Plan of Podlaskie Voivodship]; Regional Council of Podlaskie Voivodship: Białystok, Poland, 2017.

- Uchwała nr XXXIX/832/18 Sejmiku Województwa Warmińsko-Mazurskiego. z Dnia 28 Sierpnia 2018 r. w Sprawie Uchwalenia Planu Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Warmińsko-Mazurskiego. [Resolution No. XXXIX/832/18 of the Regional Council of the Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodeship of 28 August 2018 on the Adoption of the Warmińsko-Mazurskie Spatial Development Plan]; Regional Council of Podlaskie Voivodship: Białystok, Poland, 2018.

- Uchwała nr 318/XXX/16 Sejmiku Województwa Pomorskiego. z Dnia 29 Grudnia 2016 r. w Sprawie Uchwalenia Nowego Planu Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Pomorskiego. [Resolution No. 318/XXX/16 of the Regional Council of the Pomeranian Voivodeship of 29 December 2016 on the Adoption of a New Spatial Development Plan in Pomerania]; Regional Council of Podlaskie Voivodship: Białystok, Poland, 2016.

- Uchwała Nr 22/18. Sejmiku Województwa Mazowieckiego z Dnia 19 Grudnia 2018 r. w sprawie Planu Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Województwa Mazowieckiego. [Resolution No. 22/18 of the Regional Council of the Mazowieckie Voivodship of 19 December 2018 on the Spatial Development Plan of the Mazowieckie Voivodship]; Regional Council of Podlaskie Voivodship: Białystok, Poland, 2018.

- Uchwała Nr XLVII/732/18 Sejmiku Województwa Małopolskiego z Dnia 26 Marca 2018 r. w Sprawie Zmiany Uchwały Nr XV/174/03 Sejmiku Województwa Małopolskiego z Dnia 22 Grudnia 2003 roku w Sprawie Uchwalenia Planu Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Województwa Małopolskiego. [Resolution No. XLVII/732/18 of the Regional Council of Małopolskie Voivodeship of 26 March 2018 on the amendment of Resolution No. XV/174/03 of the Regional Council of Małopolskie Voivodeship of 22 December 2003 on the adoption of the spatial development plan of Małopolskie Voivodeship; Regional Council of Podlaskie Voivodship: Białystok, Poland, 2003.

- Uchwała nr LIX/930/18 Sejmiku Województwa Podkarpackiego. z Dnia 27 Sierpnia 2018 r. Zmieniająca Uchwałę w Sprawie Uchwalenia Planu Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Województwa Podkarpackiego. [Resolution No. LIX/930/18 of the Regional Council of the Podkarpackie Voivodeship of 27 August 2018 Amending the Resolution on the Adoption of the Spatial Development Plan of the Podkarpackie Voivodeship]; Regional Council of Podlaskie Voivodship: Białystok, Poland, 2018.

- Uchwała nr XI/162/2015 Sejmiku Województwa Lubelskiego. z Dnia 30 Października 2015r. w Sprawie Uchwalenia Planu Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Województwa Lubelskiego. [Resolution No. XI/162/2015 of the Regional Council of Lublin Voivodeship of 30 October 2015 on the Adoption of the Spatial Development Plan of Lublin Voivodeship]; Regional Council of Lublin Voivodeship: Lublin, Poland, 2015.

- Uchwała Nr XIX/482/20 Sejmiku Województwa Dolnośląskiego z Dnia 16 Czerwca 2020 r. w Sprawie Uchwalenia Planu Zagospodarowania Województwa Dolnośląskiego. [Resolution No. XIX/482/20 of the Regional Council of the Dolnośląskie Voivodship of 16 June 2020 on the Adoption of the Development Plan of the Dolnośląskie Voivodship]; Regional Council of the Dolnośląskie Voivodship: Vroclav, Poland, 2020.

- Uchwała Nr 14/588/18 Zarządu Województwa Kujawsko-Pomorskiego z Dnia 12 Kwietnia 2018 r. w Sprawie Przyjęcia Projektu Planu Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Województwa Kujawsko-Pomorskiego. [Resolution No. 14/588/18 of the Management Board of Kujawsko-Pomorskie Voivodship of 12 April 2018 on the Adoption of the Draft Spatial Development Plan of Kujawsko-Pomorskie Voivodship]; Management Board of Kujawsko-Pomorskie Voivodship: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 2018.

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Środowiska z dnia 12 maja 2005 r. w sprawie sporządzania projektu planu ochrony dla parku narodowego, rezerwatu przyrody i parku krajobrazowego, dokonywania zmian w tym planie oraz ochrony zasobów, tworów i składników przyrody. [Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of May 12, 2005, on the preparation of a protection plan for a national park, nature reserve, and landscape park, making changes to this plan, and protecting the resources, formations, and components of nature]. J. Laws 2005, 94, 794.

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Środowiska z Dnia … w Sprawie Ustanowienia Planu Ochrony dla Bieszczadzkiego Parku Narodowego (PROJEKT). [Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of (…) the Establishment of a Protection Plan for Bieszczady National Park (PROJECT)]. Available online: www.bdpn.pl/dokumenty/plan_ochrony/rozp_projekt_bdpn.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Środowiska z Dnia … 2018 r. w Sprawie Ustanowienia Planu Ochrony dla Kampinoskiego Parku Narodowego (PROJEKT). [Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of (…) 2018 on the Establishment of a Protection Plan for Kampinos National Park (PROJECT)]. Available online: https://bip.kampinoski-pn.gov.pl/ (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Zarządzenie Ministra Klimatu i Środowiska z dnia 30 grudnia 2021 r. w sprawie zadań ochronnych dla Kampinoskiego Parku Narodowego na rok 2022. [Order of The Minister of Climate and Environment of 30 December 2021 on protective tasks for Kampinos National Park for 2022]. Off. J. 2021, 103.

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Środowiska z dnia 7 listopada 2014 r. w sprawie ustanowienia planu ochrony dla Białowieskiego Parku Narodowego. [Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of November 7, 2014, on the establishment of a protection plan for the Białowieża National Park]. J. Laws 2014, 1735.

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Środowiska z dnia 16 września 2020 r. w sprawie ustanowienia planu ochrony dla Poleskiego Parku Narodowego. [Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of 16 September 2020 on the establishment of a protection plan for Polesie National Park]. J. Laws Repub. Pol. 2020, 1966.

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Klimatu i Środowiska z dnia 25 marca 2021 r. w sprawie ustanowienia planu ochrony dla Karkonoskiego Parku Narodowego. [Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of 25 March 2021 on the establishment of a protection plan for Karkonosze National Park]. J. Laws Repub. Pol. 2021, 882.

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Klimatu i Środowiska z dnia 6 lipca 2021 r. w sprawie ustanowienia planu ochrony dla Tatrzańskiego Parku Narodowego. [Regulation of The Minister of Climate and Environment of 6 July 2021 on the establishment of a protection plan for Tatra National Park]. J. Laws Repub. Pol. 2021, 1462.

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Środowiska z dnia 15 grudnia 2008 r. w sprawie ustanowienia planu ochrony dla Parku Narodowego “Bory Tucholskie”. [Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of December 15, 2008, on the establishment of a protection plan for the “Bory Tucholskie” National Park]. J. Laws 2008, 230, 1545.

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Środowiska z dnia 19 kwietnia 2018 r. w sprawie ustanowienia planu ochrony dla Roztoczańskiego Parku Narodowego. [Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of 19 April 2018 on the establishment of a protection plan for Roztocze National Park]. J. Laws Repub. Pol. 2018, 1081.

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Środowiska z dnia 22 lipca 2019 r. w sprawie ustanowienia planu ochrony dla Babiogórskiego Parku Narodowego. [Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of 22 July 2019 on the establishment of a protection plan for Babia Góra National Park]. J. Laws Repub. Pol. 2019, 1699.

- Uchwała Nr XIX/368/12 Sejmiku Województwa Warmińsko-Mazurskiego z dnia 28 sierpnia 2012 r. w sprawie ustanowienia Planu Ochrony Mazurskiego Parku Krajobrazowego. [Resolution No. XIX/368/12 of the Regional Council of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship dated August 28, 2012, regarding the adoption of protection plan for Masurian Landscape Park]. Off. J. 2012, 2722.

- Funkcjonowanie Międzynarodowego Rezerwatu Biosfery “Karpaty Wschodnie”. Informacja o Wynikach Kontroli. 2017. LRZ.410.004.00.2017, Nr ewid. 145/2017/P/17/095/LRZ [Functioning of the International Biosphere Reserve Eastern Carpathian, 2017]. Available online: https://www.nik.gov.pl/kontrole/P/17/095/LRZ/ (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Špulerová, J.; Piscová, V.; Matušicová, N. The Contribution of Scientists to the Research in Biosphere Reserves in Slovakia. Land 2023, 12, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewski, R.; Weigle, A. (Eds.) Różnorodność Biologiczna Polski; Drugi Polski Raport—10 lat po Rio; Narodowa Fundacja Ochrony Środowiska: Warszawa, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ramowa Konwencja o ochronie i z równoważonym rozwoju Karpat, sporządzona w Kijowie dnia 2 maja 2003 r. [Framework Convention on the Protection and Sustainable Development of the Carpathians, signed in Kiev on May 2, 2003]. J. Laws 2007, 96, 634.

- Büscher, B.; Fletcher, R. Towards Convivial Conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2019, 17, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschenbrand, E.; Michler, T. Why Do UNESCO Biosphere Reserves Get Less Recognition Than National Parks? A Landscape Research Perspective on Protected Area Narratives in Germany. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira Terra, T.; Ferreira dos Santos, R.; Cortijo Costa, D. Land use changes in protected areas and their future: The legal effectiveness of landscape protection. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maikhuria, R.K.; Nautiyal, S.; Rao, K.S.; Saxena, K.G. Conservation policy-people conflicts: A case study from Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve (a World Heritage Site), India. For. Policy Econ. 2001, 2, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, F.; Merlin, C.; Job, H. Biosphere reserves and their contribution to sustainable development. Z. Für Wirtsch. 2014, 58, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cuong Chu Dart, P.; Dudlex, N.; Hockings, M. Factors influencing successful implementation of Biosphere Reserves in Vietnam: Challenges, opportunities and lessons learnt. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 67, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Matar, D.A.; Brandon, P.A. UNESCO Biosphere Reserve management evaluation: Where do we stand and what’s next? Int. J. UNESCO Biosph. Reserves 2017, 1, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrofanenko, T.; Snajdr, J.; Muhar, A.; Penker, M.; Schauppenlehner-Kloyber, E. Biosphere Reserve for All: Potentials for Involving Underrepresented Age Groups in the Development of a Biosphere Reserve through Intergenerational Practice. Environ. Manag. 2018, 62, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedden-Dunkhorst, B.; Schmitt, F. Exploring the Potential and Contribution of UNESCO Biosphere Reserves for Landscape Governance and Management in Africa. Land 2020, 9, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, U. Biosphere Reserves of India: Issues of Conservation and Conflict. J. Anthropol. Surv. India 2019, 68, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Valenzuela, V.; Alpízar, F.; Ramírez, K.; Bonilla, S.; van Lente, H. At a conservation cross-road: The Bahoruco-Jaragua-En-riquillo Biosphere Reserve in the Dominican Republic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohedano Roldán, A. Political Regime and Learning Outcomes of Stakeholder Participation: Cross-National Study of 81 Biosphere Reserves. Sustainability 2017, 9, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, E.; Olsson, A. The Process of Creating Biosphere Reserves. An Evaluation of Experiences from Implementation Processes in five Swedish Biosphere Reserves; Report 6563; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013; 89p. [Google Scholar]

- Selinske, M.J.; Cooke, N.; Torabi, B.; Hardy, M.J.; Knight, A.T.; Bekessy, S.A. Locating financial incentives among diverse motivations for long-term private land conservation. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomination Form for the Biosphere Reserve “Roztocze” from the UNESCO Man and Biosphere Programme, Roztocze National Park, Zwierzyniec, April 2018. Available online: https://roztoczanskipn.pl/files/trb-roztocze/TRB%20ROZTOCZE_FOR/FORMULARZ_NOMINACYJNY_RB_ROZTOCZE.14-04-2023 (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Schliep, R.; Stoll-Kleemann, S. Assessing governance of biosphere reserves in Central Europe. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschenbrand, E. How Can We Promote Sustainable Regional Development and Biodiversity Conservation in Regions with Demographic Decline? The Case of UNESCO Biosphere Reserve Elbe River Landscape Brandenburg, Germany. Land 2022, 11, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, J.; Koch, M.A. Policy mixes for biodiversity: A diffusion analysis of state-level citizens’ initiatives in Germany. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2022, 24, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammadova, A.; Redkin, A.; Beketova, T.; Smith, C.D. Community Engagement in UNESCO Biosphere Reserves and Geoparks: Case Studies from Mount Hakusan in Japan and Altai in Russia. Land 2022, 11, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, P.; Igoe, J.; Brockington, D. Parks and Peoples: The Social Impact of Protected Areas. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2006, 35, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.G.; Godmaire, H.; Abernethy, P.; Guertin, M.A. Building a community of practice for sustainability: Strengthening learning and collective action of Canadian biosphere reserves through a national partnership. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cuong Chu Dart, P.; Hockings, M. Biosphere reserves: Attributes for success. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 188, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.F.; Zimmermann, H.; Santos, R.; Von Wehrden, H. Biosphere Reserves’ Management Effectiveness—A Systematic Literature Review and a Research Agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, I.; Fredholm, S.; Knez, I.; Gustavsson, E.; Weller, J. Cultural Values of Landscapes in the Practical Work of Biosphere Reserves. Land 2023, 12, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalik, S. Ogólne informacje o projektowanym Turnickim Parku Narodowym. In Turnicki Park Narodowy w Polskich Karpatach Wschodnich. Dokumentacja Projektowa; Polska Fundacja Ochrony Przyrody Pro Natura: Kraków, Poland, 1993; pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Opinia Państwowej Rady Ochrony Przyrody w Sprawie Projektu Utworzenia Turnickiego Parku Narodowego, nr ROP-0021-PWiR-33/93 z 08.02.1994 r. [Opinion of the State Council for Nature Conservation on the Project to Establish the Turnicki National Park, no. ROP-0021-PWiR-33/93 of February 8] 1994. Expert opinion, unpublished.

- Bara, I.; Boćkowski, M.; Radosław, M. (Eds.) Projektowany Turnicki Park Narodowy. Stan Walorów Przyrodniczych—35 lat od Pierwszego Projektu Parku Narodowego na Pogórzu Karpackim; Fundacja Dziedzictwo Przyrodnicze: Nowosiółki Dydyńskie, Poland, 2018; 400p, Available online: https://ruj.uj.edu.pl/xmlui/handle/item/68059 (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Impact of War on Natural Environment of the Carpathians in Ukraine; Report; Ministry of Climate and Environment of Poland Department of Nature Conservation, 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/attachment/9ed63b69-87d8-4c52-a74a-1c88385f5508 (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Jae-Hyuck, L. Analyzing local opposition to biosphere reserve creation through semantic network analysis: The case of Baekdu mountain range, Korea. Land Use Policy 2022, 82, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sena-Vittini, M.; Gomez-Valenzuela, V.; Ramirez, K. Social perceptions and conservation in protected areas: Taking stock of the literature. Land Use Policy 2023, 131, 106696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.W. An assessment of land cover change as a source of information for conservation planning in the Vhembe Biosphere Reserve. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 82, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K.; Pearce, J.; Dowling, R.; Goh, E. Pro-environmental behaviours in protected areas: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 41, 100943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohedano Roldán, A.; Duit, A.; Schultz, L. Does stakeholder participation increase the legitimacy of nature reserves in local communities? Evidence from 92 Biosphere Reserves in 36 countries. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2019, 21, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S. The Politics of the Earth. Environmental Discourses; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, E.; Fazey, I.; Christie, M.; Galdies, C. Choosing landscapes for protection: Comparing expert and public views in Gozo, Malta. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dołzbłasz, S. Uwarunkowania przyrodnicze we współpracy transgranicznej finansowanej z funduszy UE w Polsce. Probl. Ekol. Kraj. 2010, 26, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski, A.; Seidlová, A. UNESCO Transboundary Biosphere Reserves as laboratories of cross-border cooperation for sustainable development of border areas. The case of the Polish–Ukrainian borderland. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2022, 57, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczyk-Dynowska, A. Rozwój Regionalny na Obszarach Chronionych; Seria Monografie CLXVIII; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lewkowicz, Ł. Europejskie Ugrupowania Współpracy Terytorialnej—Nowa jakość polsko-słowackiej współpracy transgranicznej? Stud. Reg. I Lokal. 2013, 1, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przygotowanie Programu Współpracy Transgranicznej INTERREG 2021–2027 Pomiędzy Polską i Słowacją. Analiza Społeczno-Gospodarcza Obszaru Wsparcia, 2020, Warszawa, Maszynopis. Available online: www.ecorys.pl (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Skorokhod, I.; Rebryna, N. Prospects for the development of Ukrainian-Polish cross-bordert cooperation in the environmental sphere. Econ. Reg. Stuidies (Stud. Ekon. I Reg.) 2023, 16, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewkowicz, Ł. Uwarunkowania i formy instytucjonalnej polsko-czeskiej współpracy transgranicznej. Przegląd Geogr. 2019, 91, 511–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radecki, W. Ochrona walorów turystycznych w ramach ochrony krajobrazu w prawie polskim, czeskim i słowackim. In Prawne Aspekty Podróży i Turystyki—Historia i Współczesność: Prace Poświęcone Pamięci Profesora Janusza Sondla; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego: Kraków, Poland, 2018; pp. 409–424. [Google Scholar]

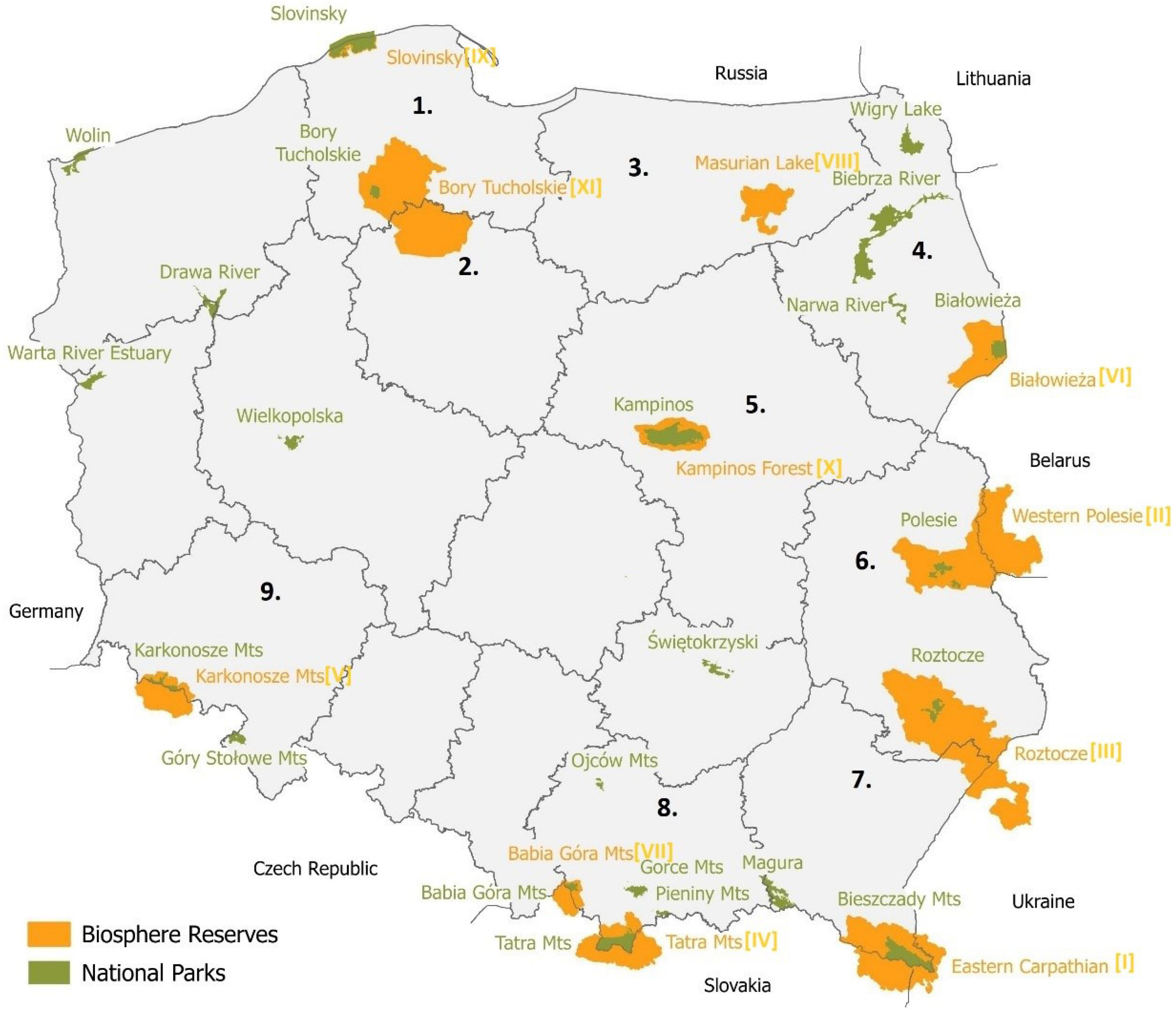

| No | Biosphere Reserve | National Forms of Nature Conservation | Year of Appointment | Surface | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (Core, Buffer, Transition Zone) | Core Zone | |||||

| ha | ha | % | ||||

| Transboundary Biosphere Reserves | ||||||

| I. | Eastern Carpathian Mts International BR (Poland-Slovakia-Ukraine) | Poland–Bieszczady National Park, Natural Landscape Parks: Ciśnieńsko-Wetliński, San Valley; Ukraine–Użanski National Park, Nadsansky Regional Landscape Park; Slovakia–Poloniny National Park | 1992/1998 | 109,694 | 18,536 | 16.9 |

| II. | Western Polesie Transboundary BR (Poland-Belarus-Ukraine) 1 | Poland–West Polesie Biosphere Reserve: Polesie National Park with a buffer zone, Sobiborski Landscape Park; Ukraine–BR of Shatsk Raion: Szacki National Park; Belarus–“Polesie Nadbużańskie” BR | 2012 | 139,917 (Poland) | about 5200 (Poland) | about 3.7 (Poland) |

| III. | Roztocze Transboundary BR (Poland-Ukraine) | Poland–core zone: Roztocze National Park, Nature Reserves: Św. Roch. Debry, Bukowy Las, Nad Tanwią, Czartowe Pole, Jalinka and Źródła Tanwi; buffer zone: Landscepe Parks: Szczebrzeszyn LP, Krasnobród LP, South Roztocze LP, Solska Forest (with nature reserves: Zarośle, Sołokija); part of the buffer zone of Roztocze National Park; Ukraine–core zone: Roztocze Nature Reserve, Yavoryvskyi National Nature Park, Nemyriv Nature Reserve, some areas of Roztocze Rawskie Regional Landscape Park; buffer zone: buffer zone of Roztocze Nature Reserve, recreation area of Yavoryvskyi National Nature Park, Roztocze Rawskie Regional Landscape Park | 2019 | 371,902 297,015 (Poland) 74,887 (Ukraine) | 12,474 9149 (Poland) 3325 (Ukraine) | 3.4 3.1 (Poland) 4.4 (Ukraine) |

| IV. | Transboundary BR of Tatra Mts (Poland-Slovakia) | Poland–Tatra Mts National Park; Slovakia–Tatra Mts National Park with buffer zone | 1992 | 126,056 20,396 (Poland) 105,660 (Slovakia) | 56,992 7548 (Poland) 49,444 (Slovakia) | 45.2 37 (Poland) 46.8 (Slovakia) |

| V. | Karkonosze Mts BR (Poland-Bohemia) | Poland–Karkonosze Mts National Park with buffer zone; Bohemia–Karkonosze Mts National Park with buffer zone | 1992 | 71,799 16,830 (Poland) 54,969 (Bohemia) | 9636 1717 (Poland) 7919 (Bohemia) | 13.4 10.2 (Poland) 14.4 (Bohemia) |

| Polish biosphere reservates | ||||||

| VI. | Białowieża Forest BR | Białowieża Forest National Park | 1976, extension in 2005 | 92,399 | 21,946 | 23.8 |

| VII. | Babia Góra BR | Babia Góra National Park | 1976, loss of status in 1997, regained status in 2001 | 11,829 | 1062 | 9 |

| VIII. | Masurian Lakes 2 BR | Łuknajno Lake Nature Reserve, Masurian Lakes Landscape Park | 2017 2 | 57,600 | ||

| IX. | Slowinski BR | Slowinski Biosphere Reserve | 1976 | |||

| X. | Kampinos Forest BR | Kampinos Forest National Park with buffer zone | 2000 | 76,232 | 5675 | 7.4 |

| XI. | Bory Tucholskie BR | Bory Tucholskie National Park, Landscape Parks: Tucholski, Wdecki, Wdzydzki, Zaborski | 2010 | 319,500 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raszka, B.; Hełdak, M. Implementation of Biosphere Reserves in Poland–Problems of the Polish Law and Nature Legacy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115305

Raszka B, Hełdak M. Implementation of Biosphere Reserves in Poland–Problems of the Polish Law and Nature Legacy. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115305

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaszka, Beata, and Maria Hełdak. 2023. "Implementation of Biosphere Reserves in Poland–Problems of the Polish Law and Nature Legacy" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115305

APA StyleRaszka, B., & Hełdak, M. (2023). Implementation of Biosphere Reserves in Poland–Problems of the Polish Law and Nature Legacy. Sustainability, 15(21), 15305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115305