Psychometric Properties of the Slovenian Version of the Brief Sense of Community Scale

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- Need fulfillment through belonging to the community;

- -

- A sense of belonging and interconnectedness or a sense of membership; this sense marks the boundary between those who belong and those who do not belong to the community;

- -

- A sense of importance to the community and, conversely, a sense of importance and influence in the community;

- -

- Shared emotional connectedness or feelings of commitment to the community and shared emotions; it is a sense of deep involvement in collective experiences.

- -

- Fulfillment of neighborhood needs;

- -

- Membership or affiliation with the neighborhood in which one lives;

- -

- Influence or sense of positive interaction between neighbors;

- -

- Emotional relationship with the neighborhood.

Problem of the Study

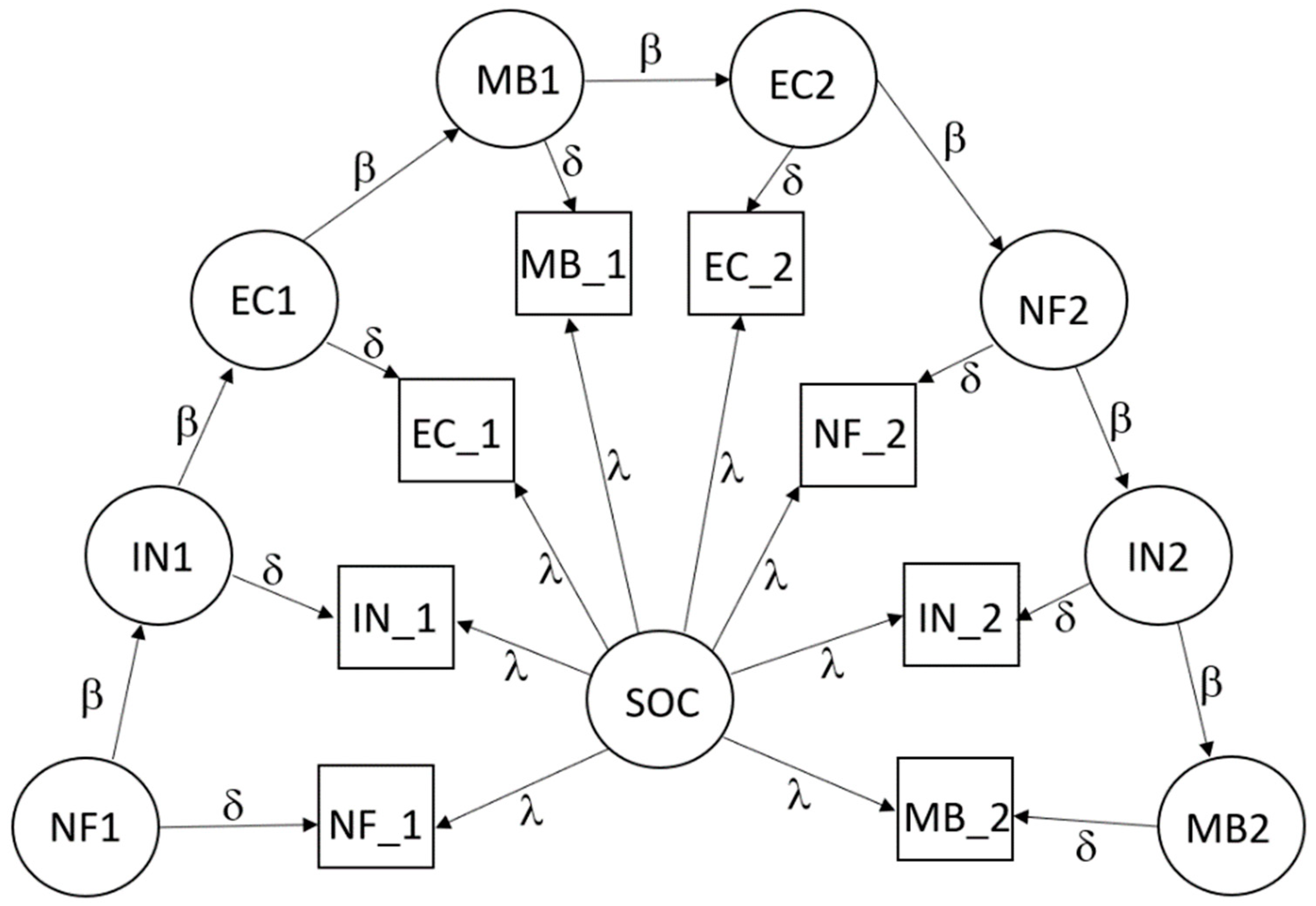

- The original second-order model [4] that includes four first-order factors and one second-order general factor;

- The one-factor congeneric model, thus simplifying the original model by omitting the first-order factors;

- The four-factor model with a moving-average structure of unique factors;

- The one-factor model with a moving-average structure of unique factors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instrument

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

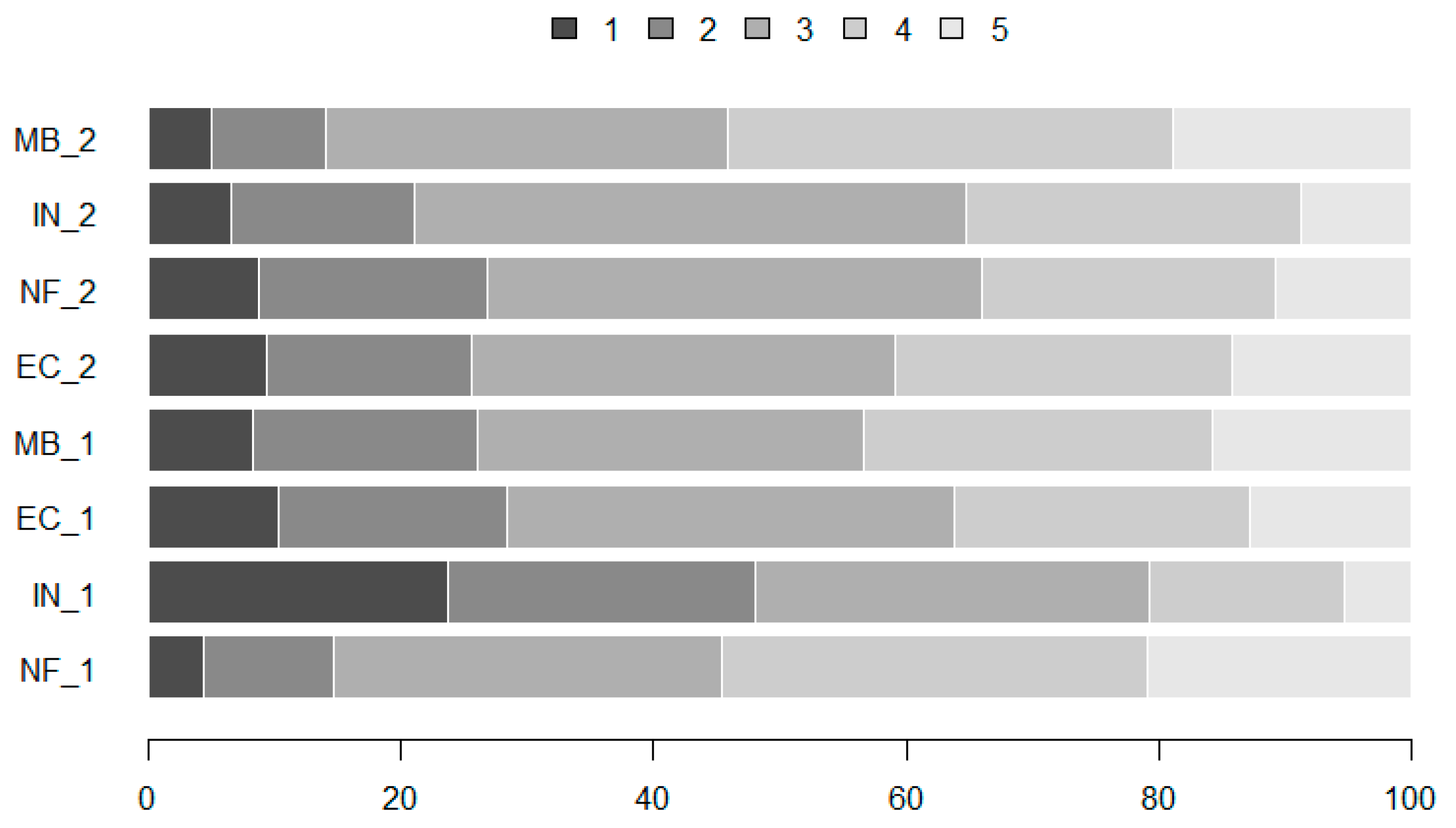

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Internal Structure

3.3. Reliability

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akbarinejad, T.; Salaj, A.T.; Johansen, A. Implementing the Integrated Social Sustainability Assessment to Norway: A Citizen-Centric and Expert-Weighted Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.M.; Ferrari, J.R. Identification among first-generation citizen students and first-generation college students: An exploration of school sense of community. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 43, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S.Y.; Chowdhury, H.R.; Qusar, M.S.; Hafez, M.A. Cross cultural adaptation & psychometric validation of research instruments: A methodological review. J. Behav. Health 2016, 5, 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, N.A.; Speer, P.W.; McMillan, D.W. Validation of a brief sense of community scale: Confirmation of the principal theory of sense of community. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 36, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.W.; Chavis, D. Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, I.; Lardier, D.T.; Garcia-Reid, P.; Reid, R.J. Testing the Factor Structure of the Brief Sense of Community Scale among Black Girls and the Relationship with Ethnic Identity, Empowerment and Social Support. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 127, 106095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardier, D.T., Jr.; Opara, I.; Cantu, I.; Garcia-Reid, P.; Reid, R.J. The brief sense of community scale: Testing dimensionality and measurement invariance by gender among Hispanic/Latinx youth. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, J.A.; Eldridge-Smith, E.D.; Kridel, M.M.; Draheim, A.A.; Stepleman, L.M. Validation of the Brief Sense of Community Scale in a lesbian, gay, and bisexual sample. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardier, D.T.; Reid, R.J.; Garcia-Ried, P. Validation of the brief sense of community scale among youth of color from an underserved urban community. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 46, 1062–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiessi, M.; Cicognani, E.; Sonn, C. Assessing Sense of Community on adolescents: Validating the brief Scale of Sense of Community in Adolescents (SOC-A). J. Community Psychol. 2010, 38, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wombacher, J.T.S.; Bürgi, T.; MacBryde, J. Measuring sense of community in the military: Cross-cultural evidence for the validity of the brief sense of community scale and its underlying theory. J. Community Psychol. 2010, 38, 671–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stračárová, J.; Halamova, J. Community Psychology in Slovakia 2015 [Komunitná Psychológia na Slovensku 2015]; Halamova, J.S., Ed.; Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2015; Chapter 3; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Halamova, J. Psychological sense of community: Examining McMillan—Chavis’ and Peck’s concepts. Stud. Psychol. 2001, 43, 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Segarra, E.; Rivera-Medina, C.L.; Varas-Diaz, N. Validating the factor structure of the brief sense of community scale with a musical community in Puerto Rico. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 44, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, T.K.K.; Burnette, D. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Brief Sense of Community Scale for Spanish-Speaking Older Adults in Puerto Rico. Innov. Aging 2020, 4, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, A.; Lai, D.W.; Yip, H.M.; Chan, S.; Lai, S.; Chaudhury, H.; Scharlach, A.; Leeson, G. Sense of community mediating between age-friendly characteristics and life satisfaction of community-dwelling older adults. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.-R.; Asai, K.; Hiraizumi, T.; Nakashima, K. Japanese version of the Brief Sense of Community Scale: Construct validity and reliability. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.H.; Nagakawa, Y.; Kobayashi, Y. Conditions under which rural-to-urban migration enhances social and economic sustainability of home communities: A case study in Vietnam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajda, A.; Oie, M. Between Individualism and Collectivism: Perception and Profiles of Creativity in Poland and Japan. Creativity. Theor. Res. Appl. 2017, 4, 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D.; Coon, H.M.; Kemmelmeier, M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 3–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobal Grum, D. Knowing, Wanting, Feeling [Vem, Hočem, Čutim]; Znanstvena založba, Univerza v Ljubljani: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Green, S.B.; Hershberger, S.L. Correlated errors in true score models and their effect on coefficient alpha. Struct. Equ. Model. 2000, 7, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stekhoven D., J.; Buehlmann, P. MissForest - non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Multimodel inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol. Methods Res. 2004, 33, 261–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.I.; Kono, A.; Yoshiyuki, N.; Kang, J. Korean translation and validation of the Community Commitment Scale for preventing social isolation in older adults. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2018, 18, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstede, G. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and its Importance for Survival; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis, H.C. Individualism and Collectivism; Westview: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 264–265. [Google Scholar]

| Item | Label | M | Mdn | SD | Skew. | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NF_1 | 3.56 | 4 | 1.07 | −0.45 | −0.33 |

| 2 | IN_1 | 2.54 | 3 | 1.16 | 0.25 | −0.80 |

| 3 | EC_1 | 3.10 | 3 | 1.15 | −0.10 | −0.69 |

| 4 | MB_1 | 3.25 | 3 | 1.17 | −0.21 | −0.76 |

| 5 | EC_2 | 3.20 | 3 | 1.15 | −0.21 | −0.68 |

| 6 | NF_2 | 3.09 | 3 | 1.09 | −0.09 | −0.51 |

| 7 | IN_2 | 3.16 | 3 | 1.00 | −0.20 | −0.16 |

| 8 | MB_2 | 3.54 | 4 | 1.05 | −0.49 | −0.17 |

| Sum | 25.45 | 26 | 6.82 | −0.09 | −0.46 |

| NF_1 | IN_1 | EC_1 | MB_1 | EC_2 | NF_2 | IN_2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IN_1 | 0.30 | ||||||

| EC_1 | 0.18 | 0.58 | |||||

| MB_1 | 0.16 | 0.53 | 0.88 | ||||

| EC_2 | 0.18 | 0.50 | 0.78 | 0.82 | |||

| NF_2 | 0.29 | 0.49 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.69 | ||

| IN_2 | 0.19 | 0.48 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.64 | |

| MB_2 | 0.17 | 0.42 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.63 | 0.60 |

| Model | χ2 | df | p | RMSEA | CFI | SRMR | AIC | SABIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1F | 99.0 | 20 | <0.001 | 0.115 | 0.952 | 0.044 | 9599.2 | 9615.9 |

| 4F | 63.8 | 14 | <0.001 | 0.109 | 0.971 | 0.038 | 9556.3 | 9579.3 |

| 4F vs. 1F | 45.5 | 6 | <0.001 | |||||

| 1F-MA | 22.1 | 13 | 0.054 | 0.042 | 0.996 | 0.023 | 9481.5 | 9505.5 |

| 1F-MA vs. 1F | 54.0 | 7 | <0.001 |

| 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item | λ | LB | UB |

| NF_1 | 0.239 | 0.146 | 0.331 |

| NF_2 | 0.811 | 0.759 | 0.863 |

| MB_1 | 0.829 | 0.780 | 0.878 |

| MB_2 | 0.786 | 0.732 | 0.840 |

| IN_1 | 0.574 | 0.506 | 0.641 |

| IN_2 | 0.793 | 0.737 | 0.849 |

| EC_1 | 0.833 | 0.785 | 0.881 |

| EC_2 | 0.862 | 0.817 | 0.907 |

| Scale | Sum Score | NF | EC | IN | MB | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | α | λ2 | ω | α | α | α | α |

| Value | 0.901 | 0.911 | 0.867 | 0.450 | 0.873 | 0.645 | 0.790 |

| LB | 0.887 | 0.899 | 0.836 | 0.340 | 0.841 | 0.577 | 0.736 |

| UB | 0.914 | 0.922 | 0.888 | 0.545 | 0.897 | 0.701 | 0.832 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sočan, G.; Kobal Grum, D. Psychometric Properties of the Slovenian Version of the Brief Sense of Community Scale. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15394. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115394

Sočan G, Kobal Grum D. Psychometric Properties of the Slovenian Version of the Brief Sense of Community Scale. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15394. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115394

Chicago/Turabian StyleSočan, Gregor, and Darja Kobal Grum. 2023. "Psychometric Properties of the Slovenian Version of the Brief Sense of Community Scale" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15394. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115394

APA StyleSočan, G., & Kobal Grum, D. (2023). Psychometric Properties of the Slovenian Version of the Brief Sense of Community Scale. Sustainability, 15(21), 15394. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115394