How to Capture Place Identity Contents? A Tool for Planning Interventions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

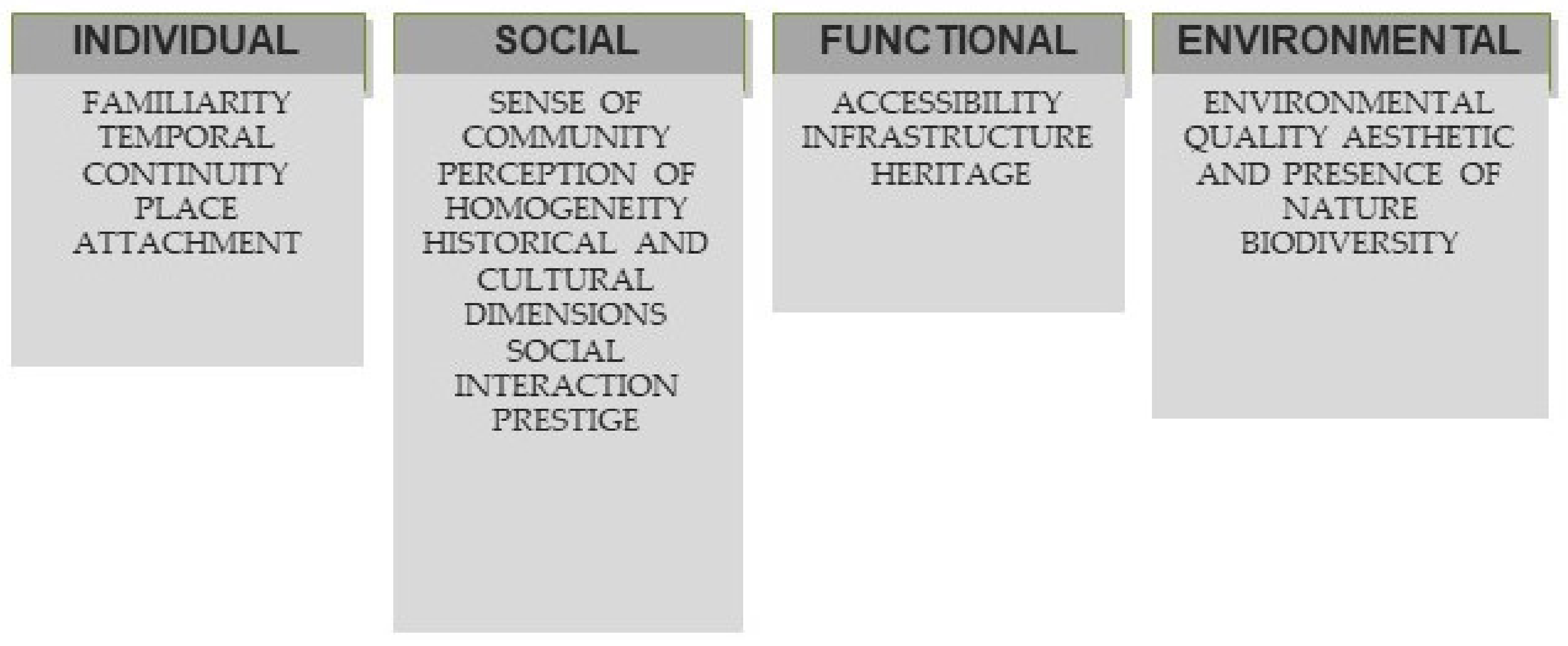

1.1. Place Identity Contents

1.2. Current Research

2. Study 1

2.1. Study Objectives

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Instruments and Procedures

Place Identity Contents Scale (PICS)

2.3. Results

2.3.1. Place Identity Contents Scale

2.3.2. Contents of Place Identity Contents, Place Identity Intensity

2.3.3. Place Identity Contents and Socio-Demographic Variables

2.3.4. Place Identity Contents, Place Identity Intensity and Town Size

3. Study 2

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Measures

3.2. Results

4. Study 3

4.1. Study Objectives

4.2. Method

4.2.1. Case Studies

4.2.2. Participants

4.2.3. Instruments and Procedure

4.3. Results and Discussion

Place Identity Contents and Place Identity Intensity

5. General Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place Identity: Physical world socialization of the self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C. Understanding the cognitive, affective and evaluative components of social urban identity: Determinants, measurement, and practical consequences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 50, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, F.; Palma-Oliveira, J.-M. Identification with the neighborhood: Discrimination and neighborhood size. Self Identity 2016, 15, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, F.; Palma-Oliveira, J.-M. Urban neighbourhoods and intergroup relations: The importance of place identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.; Durrheim, K. Displacing place-identity: A discursive approach to locating self and other. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 39, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B.; Hidalgo, M.C.; Salazar-Laplace, M.E.; Hess, S. Place attachment and place identity in natives and non-natives. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.; Murphy, C.; Lorenzoni, I. Place attachment, disruption and transformative adaptation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 55, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P. Think global, act local? The relevance of place attachments and place identities in a climate changed world. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Bunderson, S.; Foreman, P.; Gustafson, L.T.; Huff, A.S.; Martins, L.L.; Stimpert, J.L. A strategy conversation on the topic of organization identity. In Identity in Organizations. Building Theory Through Conversations; Whetten, A.D., Godfrey, P.C., Eds.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 99–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers, N.; Spears, R.; Doosje, B. Self and social identity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelal, R.; Herrera, Y.M.; Johnston, A.I.; McDermott, R. Identity as a Variable. In Measuring Identity: A Guide to Social Scientists; Abdelal, R., Herrera, Y.M., Johnston, A.I., McDermott, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 695–711. [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers, N.; Kortekaas, P.; Ouwerkerk, J.W. Self-categorisation, commitment to the group and group self-esteem as related but distinct aspects of social identity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakwell, G. Coping with Threatened Identities; Methuen, Ed.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Twigger-Ross, C.; Bonaiuto, M.; Breakwell, G. Identity theories and environmental psychology. In Psychological Theories For Environmental Issues; Bonnes, M., Lee, T.R., Eds.; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2003; pp. 203–234. [Google Scholar]

- Reicher, S.; Hopkins, N. Self and Nation: Categorization, Contestation and Mobilisation; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R. Social identity theory: Past achievements, current problems and future challenges. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 745–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalonde, R.N. Testing the social identity-intergroup differentiation hypothesis:‘We’re not American eh!’. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 41, 611–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J.C. Some current issues in research on social identity and self-categorization theories. In Social Identity; Ellemers, N., Spears, R., Doosje, B., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 6–34. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, A.; Haslam, A. The importance of social identity content in a setting of chronic social conflict: Understanding intergroup relations in Northern Ireland. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 47, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Droseltis, O.; Vignoles, V.L. Towards an integrative model of place identification: Dimensionality and predictors of intrapersonal-level place preferences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, P. Meanings of place: Everyday experience and theoretical conceptualizations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Rubio, M.Á. Local place identity: A comparison between residents of rural and urban communities. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 82, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakwell, G. Integrating paradigms: Methodological implications. In Empirical Approaches to Social Representations; Breakwell, G.M., Canter, D.V., Eds.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality; Harpers: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.M.; Altman, I. Place Attachment. In Human Behavior and Environment; Altman, I., Low, S.M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; Volume 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.P.; Lima, M.L. Análise dos conteúdos da identidade associada ao lugar. Psicologia 2005, 19, 193–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalli, M. Urban-related identity: Theory, measurement, and empirical findings. J. Environ. Psychol. 1992, 12, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaiuto, M.; Fornara, F.; Bonnes, M. Perceived residential environment quality in middle-and low-extension Italian cities. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 56, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, L.; Werner, C. Residential satisfaction among aging people living in place. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury-Bahi, G.; Félonneau, M.-L.; Marchand, D. Processes of place identification and residential satisfaction. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. What makes neighborhood different from home and city? Effects of place scale on place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, L.C. For better or worse: Exploring multiple dimensions of place meaning. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalli, M. Urban Identity. In Environmental Social Psychology; Canter, D., Jesuino, J.C., Soczka, L., Stephenson, G.M., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. Search of roots: Memory as an enabler of place attachment. In Place attachment: Advances in theory, methods and applications; Devine-Wright, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Trąbka, A. From functional bonds to place identity: Place attachment of Polish migrants living in London and Oslo. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 62, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigger-Ross, C.; Uzzell, D.L. Place and identity processes. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R. Sense of place in developmental context. J. Environ. Psychol. 1998, 18, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernandez, B. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.C.; Zhong, J.; Yu, K. Mobility and work-residence matching for new immigrants in Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Rütter, N. Is satisfaction the key? The role of citizen satisfaction, place attachment and place brand attitude on positive citizenship behavior. Cities 2014, 38, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarian, R. Social construction of places as meaningful objects: A symbolic interactionist approach. Int. Rev. Sociology 2023, 2023, 2259060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera, S.; Guardia, J. Urban social identity and sustainability: Barcelona’s Olympic Village. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G. From History to Heritage—From Heritage to Identity: In search of concepts and models. In Marketing in the Tourism Industry: The Promotion of Destination Regions; Goodall, B., Ashworth, G., Eds.; Routledge Library Editions: Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 9780203066966. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, B.; Howard, P. Introduction: Heritage and Identity. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Graham, B., Howard, P., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Hampshire, UK, 2008; pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-0-7546-4922-9. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The History of Heritage. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Graham, B., Howard, P., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Hampshire, UK, 2008; pp. 19–36. ISBN 978-0-7546-4922-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R. Testing the dimensionality of place attachment in recreational settings. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udir-Mišič, K.; Podnar, K. Perception of city management, fellow residents, and Perceived External Prestige (PEP) as antecedents of city affective commitment—The city marketing perspective. Cities 2019, 84, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyaee, M. Assessment of urban identity through a matrix of cultural landscapes. Cities 2018, 74, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, F.; Almeida, J.; Martins, C. Urban identity and tourism: Different looks, one single place. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Urban Des. Plan. 2017, 170, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Perkins, D.; Brown, G. Place attachment in a revitalizing neighborhood: Individual and block levels of analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavis, D.M.; Pretty, G.M. Sense of community: Advances in measurement and application. J. Community Psychol. 1999, 27, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzell, D.; Pol, E.; Badenas, D. Place identification, social cohesion, and enviornmental sustainability. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 26–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, G. Changing in place? Neighbourhood change and place attachment among movers and stayers in Los Angeles. Popul. Space Place 2019, 25, e2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. The relations between natural and civic place attachment and pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Environmental identity: A conceptual and an operational definition. In Identity and the Natural Environment: The Psychological Significance of Nature; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rishbeth, C.; Powell, M. Place attachment and memory: Landscapes of belonging as experienced post-migration. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefaniak, A.; Bilewicz, M.; Lewicka, M. The merits of teaching local history: Increased place attachment enhances civic engagement and social trust. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.C. Is it really just a social construction?: The contribution of the physical environment to sense of place. Soc. Resour. 2003, 16, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, F.; Palma-Oliveira, J.M. Tell me where you live… How the perceived entitativity of neighborhoods determines the formation of impressions about their residents. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 821786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, M. Grieving for a lost home. In The Urban Condition; Duhl, L., Ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, M.B. The role of distinctiveness in social identity and group behaviour. In Group Motivation: Social Psychology Perspectives; Abrams, D., Hogg, M.A., Eds.; Harvester Wheatsheaf: London, UK, 1993; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols, D.; Shumaker, S. People in places: A transactional view of settings. In Cognition, Social Behavior and Environment; Harvey, J., Ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Reese, G.; Oettler, L.M.; Katz, L.C. Imagining the loss of social and physical place characteristics reduces place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Brown, G.; Weber, D. The measurement of place attachment: Personal, community, and environmental connections. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Shriver, C.; Tabanico, J.J.; Khazian, A.M. Implicit connections with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaiuto, M.; Aiello, A.; Perugini, M.; Bonnes, M.; Ercolani, A.P. Multidimensional perception of residential environment quality and neighbourhood attachment in the urban environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroco, J. Análise de Equações Estruturais: Report Number; Wook: Porto, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, J.; Gomes, M.C.; Ezequiel, S.; Moreira, F.; Loupa-Ramos, I. Differentiating peri-urban areas: A transdisciplinary approach towards a typology. Land Use Policy 2017, 63, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, F.; Loupa-Ramos, I.; Carvalheiro, J. Are biodiversity perception and attitudes context dependent? A comparative study using a mixed-method approach. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loupa Ramos, I.; Bianchi, P.; Bernardo, F.; Van Eetvelde, V. What matters to people? Exploring contents of landscape identity at the local scale. Landsc. Res. 2019, 44, 320–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakwell, G. Social Representational Constraints upon Identity Processes; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C.; Austin, W.G.; Worchel, S. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organ. Identity Read. 1979, 56, 9780203505916–9780203505984. [Google Scholar]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Place attachment enhances psychological need satisfaction. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 359–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECTP-CEU. The Charter of European Planning Retrieved. 2013. Available online: http://www.ectp-ceu.eu/index.php/en/publications-8/the-charter-of-european-planning-213 (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, F.R.; Butler, K. Planning and Urban Design Standards; John Wiley Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The UNESCO Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. Report of the Second Consultation on its Implementation by Member States. 2019. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/hul/ (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Hall, P.; Tewdwr-Jones, M. Urban and Regional Planning, 6th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-351-26188-3. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, E.H.d.S. Place branding in strategic spatial planning: A content analysis of development plans, strategic initiatives and policy documents for Portugal 2014–2020. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2015, 8, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margarisová, K.; Vokáčová, L. Regional Branding: Building Brand Value. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2016, 64, 2059–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszczynska-Kurasinska, M.; Domaradzka, A.; Wnuk, A.; Oleksy, T. Intrinsic Value and Perceived Essentialism of Culture Heritage Sites as Tools for Planning Interventions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolo, M.G.; Servidio, R.; Palermiti, A.L.; Nappa, M.R.; Costabile, A. Pro-Environmental Behaviors and Well-Being in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Place Attachment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selman, P. Sustainable Landscape Planning. In The Reconnection Agenda; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 9780203119860. [Google Scholar]

| Age | Place of Residence Dimension | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Mean (SD) | Big City (%) | Medium City (%) | Town or Village (%) | |

| Male | 156 (37%) | 39.35 (17.23) | 18 (11.5) | 79 (50.6%) | 59 (37.8%) |

| Female | 266 (63%) | 36.88 (17.00) | 27 (10.2) | 145 (54.5%) | 94 (35.3%) |

| Total | 422 | 37.79 (17.08) | 45 (10.7) | 224 (53.1%) | 153 (36.3%) |

| Environmental Quality | Functionality | Biodiversity | Genealogy | Historical/ Cultural | Social Networks | Homogeneity | Place Attachment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| There is a lot of noise | 0.827 | |||||||

| It is very polluted | 0.798 | |||||||

| Living here is very stressful | 0.770 | |||||||

| There is a lot of traffic | 0.711 | |||||||

| It has good infrastructure | 0.798 | |||||||

| The transport network has good connections with other locations | 0.747 | |||||||

| There are gardens and parks | 0.745 | |||||||

| I feel close to everything here | 0.660 | |||||||

| There is a diversity of plants and animals here | 0.877 | |||||||

| We feel close to nature here | 0.802 | |||||||

| This is a place surrounded by beautiful landscapes | 0.764 | |||||||

| My origins are in this place | 0.863 | |||||||

| My family lives here | 0.826 | |||||||

| Many things here remind me of my past | 0.808 | |||||||

| It is a place where traditions are kept alive | 0.872 | |||||||

| There are very characteristic traditions here | 0.853 | |||||||

| This place has an interesting historical background | 0.699 | |||||||

| It is hard to make friends here | 0.844 | |||||||

| People only have formal relationships here | 0.715 | |||||||

| People are not very sociable here | 0.708 | |||||||

| People have very similar lifestyles here | 0.902 | |||||||

| I feel that people here are very similar to each other | 0.894 | |||||||

| I cannot imagine living in a different place | 0.869 | |||||||

| Living in this place is very important to me | 0.813 | |||||||

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.85 | 0.75 |

| % Explained variance | 11.11 | 9.71 | 9.69 | 9.54 | 9.35 | 8.06 | 7.36 | 6.81 |

| % Cumulative variance | 11.11 | 20.82 | 30.50 | 40.04 | 49.39 | 57.44 | 64.80 | 71.61 |

| Mean (SD) (Study2) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CPI—Env. Quality | 4.94 (1.48) | - | 0.181 * | 0.285 ** | 0.071 | 0.006 | 0.368 ** | 0.050 | 0.067 | 0.142 ** | |

| 2. CPI—Functionality | 4.48 (1.45) | 0.054 | - | 0.105 * | −0.029 | 0.246 ** | 0.082 | 0.165 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.201 ** | |

| 3. CPI—Biodiversity | 4.48 (1.98) | 0.377 ** | 0.184 ** | - | 0.338 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.214 ** | 0.314 ** | 0.309 ** | 0.375 ** | |

| 4. CPI—Genealogy | 4.60 (2.13) | 0.144 ** | 0.055 | 0.271 ** | - | 0.258 ** | 0.125 * | 0.126 * | 0.340 ** | 0.452 ** | |

| 5. SCI-Hist-Cultural | 4.17 (1.76) | 0.199 ** | 0.251 ** | 0.394 ** | 0.364 ** | - | 0.220 ** | 0.289 ** | 0.265 ** | 0.234 ** | |

| 6. CPI-Social Networks | 4.94 (1.62) | 0.355 ** | 0.001 | 284 ** | 0.241 ** | 0.282 ** | - | −0.069 | 0.115 * | 0.168 ** | |

| 7. CPI—Homogeneity | 4.46 (1.77) | 0.088 * | 0.032 | 0.088 * | 0.155 ** | 0.085 * | 0.020 | - | 0.157 * | 0.110 * | |

| 8. CPI—Attachment | 4.56 (2.10) | 0.215 | 0.193 ** | 0.331 | 0.475 ** | 0.408 ** | 0.265 ** | 0.126 ** | - | 0.699 ** | |

| 9. Place Identity | 5.40 (1.87) | 0.277 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.382 ** | 0.454 ** | 0.407 ** | 0.312 ** | 0.005 | 0.716 ** | - | |

| 10. Place satisfaction 1 | 8.04 (2.22) | 0.283 ** | 0.253 ** | 0.263 ** | 0.152 ** | 0.177 ** | 0.167 ** | −0.080 | 0.385 ** | 0.422 ** | - |

| 11. Life quality in place 1 | −6.66 (1.76) | 0.232 ** | 0.361 ** | 0.323 ** | 0.187 ** | 0.221 ** | 0.192 ** | 0.001 | 0.281 ** | 0.355 ** | 0.393 ** |

| Mean (SD) (Study1) | 2.36 (0.99) | 4.05 (1.08) | 4.21 (1.33) | 4.04 (1.58) | 3.78 (1.27) | 2.73 (1.3) | 3.79 (1.15) | 3.84 (1.39) | 4.54 (1.30) |

| Age | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <24 | 25–49 | 50–64 | >65 | |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | F | p | |

| Genealogy | 4.36 (1.53) a | 3.80 (1.67) b | 3.95 (1.36) | 4.14 (1.48) | 3.56 | 0.014 |

| Social Networks | 2.45 (0.96) a | 2.86 (1.01) b | 3.10 (0.97) b | 2.57 (1.17) a | 7.97 | 0.000 |

| Place Attachment | 3.65 (1.34) a | 3.64 (1.32) a | 4.34 (1.36) b | 4.63 (1.39) b | 9.63 | 0.000 |

| Dimensions of the Place | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big City | Medium City | Town or Village | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | F | p | |

| Environ. Quality | 4.30 (0.97)a | 4.53 (0.93) a | 4.92 (1.01) b | 10.68 | 0.00 |

| Functionality | 4.82 (0.87) a | 4.11 (1.01) b | 3.74 (1.10) c | 19.81 | 0.00 |

| Biodiversity | 3.76 (3.37) a | 3.91 (1.30) a | 4.80 (1,14) b | 26.13 | 0.00 |

| Genealogy | 2.64 (1.50) a | 3.90 (1.56) b | 4.65 (1.30) c | 34.89 | 0.00 |

| History–Culture | 3.48 (1.46) | 3.79 (1.29) | 3.84 (1.17) | 1.41 | 0.25 |

| Social Networks | 3.85 (1.09) a | 4.29 (1.02) b | 4.63(1.00) b | 4.46 | 0.01 |

| Homogeneity | 3.60 (1.23) | 3.70 (1.14) | 3.96 (1.10) | 3.30 | 0.04 |

| Attachment | 3.31 (1.32) a | 3.84 (1.41) | 3.99 (1.34) b | 4.27 | 0.02 |

| Place Identity | 4.05 (1.49) a | 4.49 (1.26) | 4.70 (1.22) b | 4.69 | 0.01 |

| Factor Loadings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Quality | Functionality | Biodiversity | Genealogy | Historical/ Cultural | Social Networks | Homogeneity | Place Attachment | |

| There is a lot of noise | 0.78 | |||||||

| It is very polluted | 0.81 | |||||||

| Living here is very stressful | 0.69 | |||||||

| There is a lot of traffic | 0.49 | |||||||

| Infrastructure is good | 0.80 | |||||||

| Transport connections with other localities are good | 0.53 | |||||||

| There are gardens and parks | 0.48 | |||||||

| I feel close to everything | 0.72 | |||||||

| There is diversity of plants and animals | 0.81 | |||||||

| We feel close to nature | 0.90 | |||||||

| There are beautiful landscapes | 0.77 | |||||||

| My origins are here | 0.92 | |||||||

| My family lives here | 0.59 | |||||||

| Many things here remind me of my past | 0.75 | |||||||

| Traditions are kept alive here | 0.91 | |||||||

| The place has many characteristic traditions | 0.88 | |||||||

| The historical background is interesting | 0.56 | |||||||

| It is hard to make friends here | 0.73 | |||||||

| People only have formal relationships here | 0.73 | |||||||

| People are not very sociable here | 0.69 | |||||||

| People here have very similar lifestyles | 0.65 | |||||||

| People are very much alike here | 0.98 | |||||||

| I cannot imagine living in a different place | 0.69 | |||||||

| Living here is very important to me | 0.87 | |||||||

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.779 | 0.673 | 0.866 | 0.790 | 0.809 | 0.760 | 0.774 | 0.744 |

| N | Female | Age Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agualva | 111 | 60 (54%) | 47. 0 |

| Anunciada | 120 | 63 (53%) | 51.9 |

| Poceirão | 114 | 62 (54%) | 49.1 |

| Agualva Mean | Poceirão Mean | Anunciada Mean | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Quality | 3.49 a | 5.45 b | 5.16 b | 66.073 | 0.000 |

| Functional | 4.83 b | 3.34 a | 4.82 b | 44.219 | 0.000 |

| Biodiversity | 2.50 a | 5.16 b | 5.38 b | 103.248 | 0.000 |

| Genealogy | 3.53 a | 5.17 b | 4.98 b | 22.342 | 0.000 |

| History–Culture | 2.79 a | 4.08 b | 5.11 c | 54.744 | 0.000 |

| Social Networks | 4.08 a | 5.59 b | 5.12 b | 27.347 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Homogeneity | 4.22 | 4.66 | 4.59 | 2.003 | 0.136 |

| Attachment | 3.70 a | 4.99 b | 4.93 b | 13.693 | 0.000 |

| Place Identity | 4.72 a | 5.54 b | 5.97 b | 14.035 | 0.000 |

| Place Satisfaction * | 7.24 a | 8.07 b | 8.61 b | 11.857 | 0.000 |

| Place Quality of Life * | 6.28 a | 6.50 | 7.05 b | 5.832 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernardo, F.; Loupa-Ramos, I.; Coelho, R. How to Capture Place Identity Contents? A Tool for Planning Interventions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15535. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115535

Bernardo F, Loupa-Ramos I, Coelho R. How to Capture Place Identity Contents? A Tool for Planning Interventions. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15535. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115535

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernardo, Fátima, Isabel Loupa-Ramos, and Rosa Coelho. 2023. "How to Capture Place Identity Contents? A Tool for Planning Interventions" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15535. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115535

APA StyleBernardo, F., Loupa-Ramos, I., & Coelho, R. (2023). How to Capture Place Identity Contents? A Tool for Planning Interventions. Sustainability, 15(21), 15535. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115535