Good Governance, Resilience, and Sustainable Development: A Combined Analysis of USA Metropolises’ Strategies through the Lens of the 100 RC Network

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Resilience

2.2. Sustainable Development

2.3. The notion of Metropolitan Urban Governance

2.4. Good Urban Governance

2.5. Good Governance for Resilience and Sustainable Development

3. The 100 RC Network

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Combined Methodology

4.2. Research Questions

5. Content and Comparative Analysis and Outcomes

5.1. Comparing the Governance Strategies of US Metropolitan Cities

5.2. Discussion—Outcomes of the Comparative Analysis

5.2.1. Good Governance in the Metropolises’ Strategies

5.2.2. Good Governance as a Perquisite for Resilience and Sustainable Development

5.2.3. Good Governance at the Metropolitan Scale

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN, World Urbanization Prospects, The 2018 Revision. 2019. Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/publications/Files/WUP2018-Report.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Metropolis Observatory, 100 Resilient Cities, 03 Issue Paper. 2017. Available online: https://www.metropolis.org/sites/default/files/issue_paper_3-the_metropolitan_scale_of_resilience.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- UN-Habitat, Unpacking Metropolitan Governance for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/Unpacking%20Metropolitan%20Governance.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Jabareen, Y. Planning the resilient city: Concepts and strategies for coping with climate change and environmental risk. Cities 2013, 31, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaans, M.; Waterhout, B. Building up resilience in cities worldwide—Rotterdam as participant in the 100 Resilient Cities Programme. Cities 2017, 61, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croese, S.; Green, C.; Morgan, G. Localizing the Sustainable Goals Through the Lens of Urban Resilience: Lessons and Learnings from 100 Resilient Cities and Cape Town. Sustainability 2020, 12, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo Nieto, A.; Nino Amezquita, J.L. Introduction. In Metropolitan Governance in Latin America, Region and Cities Series, 1st ed.; Regional Studies Association (RSA), Capello, R., Kitchin, R., Knieling, J., Lowe, N., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, C.; Rajamani Neeli, S. Good Governance to Achieve Resiliency and Sustainable Development. In Disaster Risk Governance in India and Cross Cutting Issues, Disaster Risk Reduction; Pal, I., Shaw, R., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.; Douwes, J.; Sutherland, C.; Sim, V. Durban’s 100 Resilient Cities journey: Governing resilience from within. Environ. Urban. 2020, 32, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebrowski, C. Acting local, thinking global: Globalizing resilience through 100 Resilient Cities. New Perspect 2020, 28, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastenrath, S.; Coenen, L.; Davidson, K. Urban Resilience in Action: The Resilient Melbourne Strategy as Transformative Urban Innovation Policy? Sustainability 2019, 11, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, S.; Doyon, A. The Resilient Melbourne experiment: Analyzing the conditions for transformative urban resilience implementation. Cities 2021, 110, 103017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, K.; Gleeson, B. New Socio-ecological Imperatives for Cities: Possibilities and Dilemmas for Australian Metropolitan Governance. Urban Policy Res. 2018, 36, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derr, V.; Chawla, L.; van Vliet, W. Children as Natural Change Agents: Child Friendly Cities as Resilient Cities. In Designing Cities with Children and Young People—Beyond Playgrounds and Skate Parks; Bishop, K., Corkery, L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319501241 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Meerow, S.; Pajouhesh, P.; Miller, T.R. Social equity in urban resilience planning. Local Environ. 2019, 24, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, F.S.; Jax, K. Focusing the meaning(s) of resilience: Resilience as a descriptive concept and a boundary object. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNISDR, United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction, UN. 2009. Available online: https://www.unisdr.org/files/7817_UNISDRTerminologyEnglish.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Mensah, J. Sustainable development: Meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: Literature review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1653531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Waldt, G. The role of government in sustainable development: Towards a Conceptual and Analytical Framework for Scientific Inquiry. Adm. Publica 2016, 24, 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Metaxas, T.; Psarropoulou, S. Sustainable Development and Resilience: A Combined Analysis of the Cities of Rotterdam and Thessaloniki. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN, Human Settlements Programme, UN-HABITAT, The Global Campaign on Urban Governance Campaign Secretariat, 2nd edition. March 2002. Available online: http://www.unhabitat.org/governance (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Nel, D.; Nel, V. Governance for Resilient Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the CIB World Building Congress 2019, Hong Kong, China, 17–21 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Dool, L.; Hendriks, F.; Gianoli, A.; Schaap, L. Chapter one Introduction: Good Urban Governance: Challenges and Values. In The Quest for Good Urban Governance; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng-Odoom, F. On the origin, meaning, and evaluation of urban governance. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. 2012, 66, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P. Urban Governance for More Sustainable Cities. Eur. Env. 2000, 10, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topno, P.N.; Pal, I. Multi-stakeholder Support in Disaster Risk Governance in India. In Disaster Risk Governance in India and Cross Cutting Issues, Disaster Risk Reduction; Pal, I., Shaw, R., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badach, J.; Dymincka, M. Concept of ‘Good Urban Governance’ and Its Application in Sustainable Urban Planning. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 082017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, K.; Pimashkov, P. Good Governance in European Metropolitan Areas, Council of Europe, the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities. 2006. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/explanatory-report-good-governance-in-european-metropolitan-areas/1680719625 (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Kardos, M. The Reflection of good governance in sustainable development strategies. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.; Auriacombe, C. Good Urban Governance and City Resilience: An Afrocentric Approach to Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Peng, B.A. Framework for Resilient City Governance in Response to Sudden Weather Disasters: A Perspective Based on Accident Causation Theories. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Rockefeller Foundation. Available online: https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/100-resilient-cities/ (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Resilient Cities, Resilient Lives Learning from the 100RC Network. July 2019. Available online: https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/downloadable_resources/UR/Resilient-Cities-Resilient-Lives-Learning-from-the-100RC-Network.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

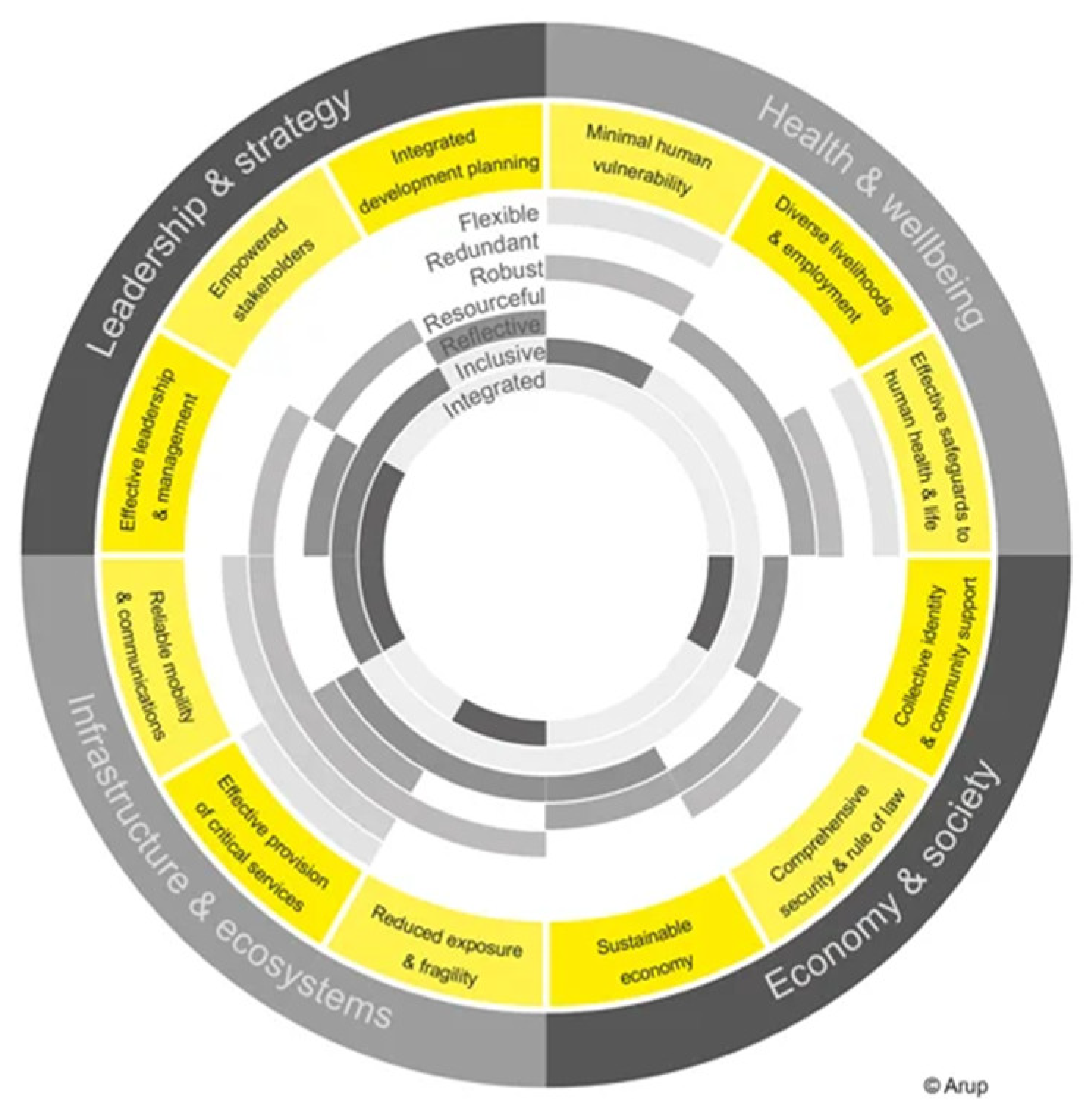

- The Rockefeller Foundation & Arup, City Resilience Framework April 2014 (Updated December 2015). Available online: https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/report/city-resilience-framework/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Arup, The Rockefeller Foundation. Available online: https://www.arup.com/-/media/arup/images/perspectives/themes/cities/city-resilience-index/cri.jpg?h=680&w=720&hash=258DE19B4463466704BE914800A29828 (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- The Rockefeller Foundation & Arup, City Resilience Framework. November 2015. Available online: https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/100RC-City-Resilience-Framework.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Eisenhardt, M.K. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.D. Content Analysis: A method in Social Science Research. In Research Methods for Social Work; Lal Das, D.K., Bhaskaran, V., Eds.; Rawat: New Delhi, India, 2008; pp. 173–193. Available online: http://www.css.ac.in/download/content%20analysis.%20a%20method%20of%20social%20science%20research.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Goodrick, D. Comparative Case Studies: Methodological Briefs—Impact Evaluation No. 9. Papers innpub754, Methodol. Briefs. 2014. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ucf/metbri/innpub754.html (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Resilient Atlanta. November 2017. Available online: https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/downloadable_resources/Network/Atlanta-Resilience-Strategy-English.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Resilient Chicago, A Plan for Inclusive Growth and a Connected City. February 2019. Available online: https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/downloadable_resources/Network/Chicago-Resilience-Strategy-English.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Resilient Houston, Resilience Strategy. Available online: https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/downloadable_resources/Network/Houston-Resilience-Strategy-English.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Resilient El Paso, Resilience Strategy. Available online: https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/downloadable_resources/Network/El-Paso-Resilience-Strategy-English.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Resilient Dallas, Dallas’ Path to Shared Prosperity. Available online: https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/downloadable_resources/Network/Dallas-Resilience-Strategy-English.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Greater Miami and the Beaches, Resilience Strategy. Available online: https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/downloadable_resources/Network/Greater-Miami-Resilience-Strategy-English.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Resilient Los Angeles, Resilience Strategy. March 2018. Available online: https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/downloadable_resources/Network/Los-Angeles-Resilience-Strategy-English.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Resilient New Orleans, Strategic Actions to Shape our Future City. Available online: https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/downloadable_resources/Network/New-Orleans-Resilience-Strategy-English.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- One New York, The Plan for a Strong and Just City. Available online: https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/downloadable_resources/Network/New-York-City-Resilience-Strategy-English.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Resilient San Fransisco, Stronger Today, Stronger Tomorrow. Available online: https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/downloadable_resources/Network/San-Francisco-Resilience-Strategy-English.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2023).

| Dimension | Drivers | Content of Driver |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership and Strategy | 10. Promotes leadership and management | Relating to government, business, and civil society. This is recognizable in trusted individuals, multistakeholder consultation, and evidence decision making. |

| 11. Empowers a broad range of stakeholders. 12. Fosters long-term and integrated planning. | Education for all, access to up-to date information, knowledge to enable people/organizations to take appropriate action. Along with education and awareness, communication is needed to ensure that knowledge is transferred between stakeholders and cities. Holistic vision, informed by data. Strategies/plans should be integrated across sectors and land use plans should consider and include different departments, users, and uses. Building codes should create safety and remove negative impacts. |

| City | Challenges | Vision | Promotes Leadership and Effective Stakeholders | Empowers a Broad Range of Stakeholders | Foster Long-Term and Integrated Planning | Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlanta | Economic and housing insecurity. Environmental stresses. Infrastructural deficiencies. | Design our systems to reflect our values. | Expand equity in sustainability training program. Develop an equity strategy among sustainability practitioners. Promote the development of an interfaith coalition. | Improve the city’s community outreach. Create an education liaison. Create a community resource center. Re-envision public libraries. Audit neighborhood planning units. Launch a participatory budgeting pilot. | Create a city investment checklist. Establish a system and evaluation process for joint infrastructure. Create an equity and resilience scorecard. | Leader in equity, sustainability, and resilience. |

| The 311 Customer Service social media platform | ||||||

| Chicago | Poverty. Socioeconomic inequality. Education. Public safety. Racism/racial equity. | Connected Chicago. | Health awareness project. Advance the community policing strategy Use behavioral science to promote resilient staff of 911 call center. | Inform system 311 for health and human services. Centralized city newsletter. Foster community preparedness. Urban heat response pilot project. Website to connect residents. | Resilience lens to hazard mitigation planning. Urban sensing program to collect real time city data. Strengthen cyber security. Disaster recovery technology infrastructure. | Regional governments are connected and work together. Residents connected to opportunity. Communities connecting with each other. |

| Houston | Lack access to basic health care. Deep segregation (income/jobs/race). Climate change impacts. Growth and development. Transformative economy. | Resilient Houston in 2050. | Encourage community leadership/stewardship/participation. Maximize access to economic opportunity and prosperity. Opportunities for more to start/maintain/grow small businesses. Prepare workforce and all youth for future jobs. | Ensure Houstonians have the information, skills, and capacity to prepare for any emergency. Mobilize Houstonians to adapt to climate change. Support small businesses to have access to information and resources. | Make streets 100% safe for all. Programming and urban design interventions. Shelter and housing for any Houstonian in need. | Emergency response stabilization. Adaptive recovery. Institutionalization. |

| El Paso | Challenges of a border metroplex. Poverty. Flash flooding. Extreme heat. Food access. Drought. Human health. | El Paso will have safe and beautiful neighborhoods, a vibrant regional economy, and exceptional recreational, cultural and educational opportunities. | Activate non-traditional tools to build productive dialog among the community. Enhance the practice of resilience within the city’s organizational structure and operations. | Connect people to citywide assets and programs. Improve conditions and enhance preparedness for low-income residents. Connect people and initiatives across the region. Activate the bi-national community. | Cultivate local/regional/global relationships supportive of cooperative building efforts. | Emergency response stabilization. Adaptive. Recovery. Institutionalization. |

| Dallas | Homelessness. Poverty. Unemployment. Social/racial inequality. Lack of reliable transportation. Violence. | Close the gap between the haves and have-nots. Restore opportunities for working families. | Drive collaborative action across sectors. Prioritize workforce readiness and training, skill development, small business capacity building, and access to wrap-around services. Regularly convene Dallas members to establish and formalize city goals and policy recommendations to guide decision making and align representation with Dallas’ priorities. | Support and partner with anchor institutions and community-based efforts for equity. Build an equitable city administration and workplace culture. Develop community leadership partnership strategy with focus on immigration reception/increasing immigrant participation in civic life. | City’s strategic plan: Dallas will be a welcoming city to immigrants and residents. Community input and data to inform of the strategic mobility plan. Collaborate with Dallas County health/human services/hospital systems to share data. Conduct a geospatial analysis of health disparities to identify specific areas of need, available resources, and gaps in services. | Effective leadership and management. Multi-stakeholder involvement. Long-term planning. Reliable communication and mobility in public health. |

| Greater Miami and the Beaches | Growing traffic congestion. Sea level rise and coastal erosion. Aging infrastructure. Decreasing housing quality and affordability. Income inequality. | By connecting, engaging, and empowering every voice in our community, we will stand strong and share our unique history in South Florida. | The 311 Contact Center. The 305 Network will support its member cities. Collaborate with universities and leverage experience. Create an advisory panel. | Increase neighborhood response. Promote volunteer opportunities. Support resilience hubs. Create a plan for resilience literacy. Support several organizations in creating visual infographics, photos, and short video vignettes to explain resilience in all its facets. | Prepare for property. Preplanning for post-disaster toolkit. Distribute resilient urban land use essential guide. Develop shared resources. Plan efficiently and effectively together. | Community cohesion. Enhance community-based interventions. Number of active volunteers. Understanding of resilience. Streamline government processes. Disaster preparedness. |

| Los Angeles | Turning L.A. into the strongest and safest city in the world. | Earthquakes/fires/ landslides/tsunami. Cyber crime and terrorism. Riots/civil unrest. Public health emergencies. | Expand the Mayor’s resilience office. Designate departmental Chief Resilience Officers. Track and report on resilience outcomes for vulnerable populations and neighborhoods. Increase real-time data gathering and sharing tools. Engage the next generation of leaders in resilience building. | Work with all neighborhood councils to develop preparedness plans. Prepare Angelenos to be self-sufficient for at least seven to fourteen days after an emergency. Build a culture of preparedness by training all city departments and employees on disaster preparedness and recovery on an annual basis. | Bring earthquake early warning technology to all Angelenos. Develop post-disaster service restoration targets for critical infrastructure. | Health and well-being. Preparedness. Strong social network. Leadership and commitment. Disaster preparedness and recovery. Financial security. Climate adaptation. Infrastructure modernization. |

| New Orleans | We are building a New Orleans for the future, one that embraces change, prepares for the risks of the future, and honors our traditions. | Environment. Climate change. Poverty and inequality. Unemployment. Public violence. Education. Public health. Housing and social mobility. Terrorism and civil unrest. Outbreaks of infectious diseases. | Integrate resilience-driven decision making across public agencies. Performance management programs. One-stop shop for city permits and licenses. Integrated asset management. | Develop the preparedness of our businesses and neighborhoods. | Promote sustainability as a growth strategy. Invest in pre-disaster planning for post-disaster recovery. | A city leader in sustainability, safety, and stability. Protection of critical financial assets. Economic development. Continuity of critical services in times of disaster. |

| New York | Become a strong and just city. | Growing population. Rising inequality. Poverty and homelessness. Aging infrastructure. Affordable housing. Developing economy. Public spaces. Urban environmental conditions and climate change. | Integrated government and social services. Increase the rate of volunteerism among New Yorkers to 25%. Build a government workforce reflective of the diversity and inclusion of communities. Improve the way N.Y. City develops and retains a diverse workforce. | Strengthen community-based organizations, civic participation, and information capacity. Improve emergency preparedness and planning. | Increase the capacity of accessible emergency shelters to 120,000 residents. Develop and adopt consistent resilient design guidelines. | Innovation. Climate change. Growing and thriving city/sustainable metropolis. Fair and equal participation. Justice. |

| San Francisco | Stronger today, stronger tomorrow. | Earthquakes. Social inequity. Unaffordability. Infrastructure. | Develop and implement a long-term recovery governance plan. Develop a 50-year long-range transportation vision. Enhance trust in public safety officials. Develop a public digital service strategy. Receive and issue permits electronically. Establish the Office of Resilience and Recovery | Build community readiness through education and technology. Increase training for neighborhood emergency response teams. Reimagine public libraries as community spaces. Partnerships to empower neighborhoods. Build capacity in community-based health organizations. The San Francisco Business Portal information. | Ensure effective city operations during response and recovery. Restore financial position. Expand access to health facilities and services for those most in need. Actively coordinate for recovery with our private and public utilities. Continue the Earthquake Safety Implementation Program. Mitigate earthquake risk through the building code. Streamline the process to quickly re-occupy buildings. Continue building and rebuilding infrastructure. Bayview Neighborhood Support Center. | Financially prepared for disaster. Education and outreach on sustainability concepts. Diverse and distinct character of neighborhoods. Seismic and environmentally conscious building improvements. Social health. Community capacity building. Collaborative community. Public digital services. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kalla, M.; Metaxas, T. Good Governance, Resilience, and Sustainable Development: A Combined Analysis of USA Metropolises’ Strategies through the Lens of the 100 RC Network. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215895

Kalla M, Metaxas T. Good Governance, Resilience, and Sustainable Development: A Combined Analysis of USA Metropolises’ Strategies through the Lens of the 100 RC Network. Sustainability. 2023; 15(22):15895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215895

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalla, Maria, and Theodore Metaxas. 2023. "Good Governance, Resilience, and Sustainable Development: A Combined Analysis of USA Metropolises’ Strategies through the Lens of the 100 RC Network" Sustainability 15, no. 22: 15895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215895

APA StyleKalla, M., & Metaxas, T. (2023). Good Governance, Resilience, and Sustainable Development: A Combined Analysis of USA Metropolises’ Strategies through the Lens of the 100 RC Network. Sustainability, 15(22), 15895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215895