1. Introduction

Several countries have achieved global economic development. In 1970, the average global economic growth was 4.36% and could support 3.76 billion people worldwide. However, global economic growth has not been accompanied by improved environmental quality, i.e., the environmental quality has been declining in several countries [

1]. The sustainable development theory is developing vastly and rapidly, but its implementation has failed due to various problems, including the need for field application [

2]. The application of a method is unsuccessful due to a lack of implementation of the plan [

3]. Sustainable development goals still need to be clarified and attainable for cities and communities in the various countries trying to implement them [

4,

5,

6]. Some authors argue that there is not only a lack of clear progress towards sustainable development but also worsening global problems [

3,

5,

7]. Therefore, the current main task is to find approaches to implementing the principles of sustainable development that guarantee sustainable results at local, national, and global levels.

Sustainable communities, such as transition towns, cohousing units, and ecovillages, emerged as a result of grassroots initiatives towards a more ecologically sound, socially just, and economically viable society. The main goal of a sustainable community is to wisely integrate social, economic, and environmental aspects through a “bottom-up” community-based approach to ensure the well-being and prosperity of its inhabitants [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Due to the mandates of these communities, they provide an ideal environment for sustainable development. A relevant community initiative is environmentally cultured villages (ecovillages). An ecovillage is defined as a holistic solution to meet the basic needs of its members with minimal environmental damage [

12].

Studies performed on sustainable communities assume that ecovillages represent model communities where people strive to conduct development according to sustainable development principles. Several authors describe this type of sustainable community as an important educational center for sustainable development [

4,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. An ecovillage has an integral role as a model that provides holistic local education, sustainable living, and village community-based sustainable development approaches [

4,

14,

16,

18].

Individuals, neighborhoods, and communities can adopt lessons learned from pilot communities, which can be applied at local, national, and global levels [

14,

18]. However, environmental experts strive to create a “holistic and sustainable culture”. The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (1992), the World Summit on Sustainable Development (2002), the Brundtland Report (1987), Agenda 21 (1992), and several authors [

4,

14,

16,

19] claim that this concept has not been studied thoroughly. Therefore, a village is considered an educational site for good sustainable development practice. Studying it, adopting achievements in sustainable development, and transferring knowledge to other fields are essential.

According to SIAK, West Java Province has an area of 35,377.76 km

2 and a population of 46,497,175 million people. This population is spread across 26 regencies and cities, 625 districts, and 5899 villages. According to [

20], West Java has the largest population compared to other provinces in Indonesia, and it increases yearly. High population numbers result in increased economic activity and the need for resources. The increased need for clothing, food, shelter, and energy, including the need for housing, results in reduced green areas due to land conversion. Watershed areas are areas experiencing increased land conversion due to an increased need for housing, food, and other resources. These conditions will cause land conversion to increase.

Land conversion in the watershed area results in changes in the hydrological conditions of the watershed, such as decreased water infiltration into the ground, increased peak discharge, discharge fluctuations between seasons, increased surface runoff, floods, and droughts. Watersheds can be viewed as natural resources in the form of stocks with various ownerships (private, common, state property). They produce goods and services for individuals, community groups, and the public and cause interdependence between parties, individuals, and community groups [

21]. Thus, a watershed can be viewed as a system. A watershed contains various interconnected components; therefore, there is a need for holistic and integrated watershed management. The Citarum River is the longest in West Java Province, stretching for 297 km from its headwaters, namely Situ Cisanti, on the slopes of Mount Wayang, Cibeureum Village, Kertasari District, Bandung Regency, to the Java Sea, which empties into the Happy Beach Village, Muara Gembong District, Bekasi Regency.

The Citarum watershed crosses 11 regencies and cities, including Bandung Regency, West Bandung Regency, Purwakarta Regency, Karawang Regency, Bekasi Regency, Bandung City, Cimahi City, parts of Sumedang Regency, parts of Cianjur Regency, parts of Bogor Regency, and parts of Garut Regency. Apart from being a source of raw water for drinking water, the Citarum River is also a source of irrigation water for hundreds of thousands of hectares of rice fields and power plants for the islands of Java and Bali. There are three reservoirs along this river: the Saguling Reservoir, Cirata Reservoir, and Jatiluhur Reservoir. In the last three decades, the Citarum River has experienced a decline in water quality and quantity as forest land has been converted into agricultural land due to rapid industrialization in the Citarum watershed and high population growth [

22,

23].

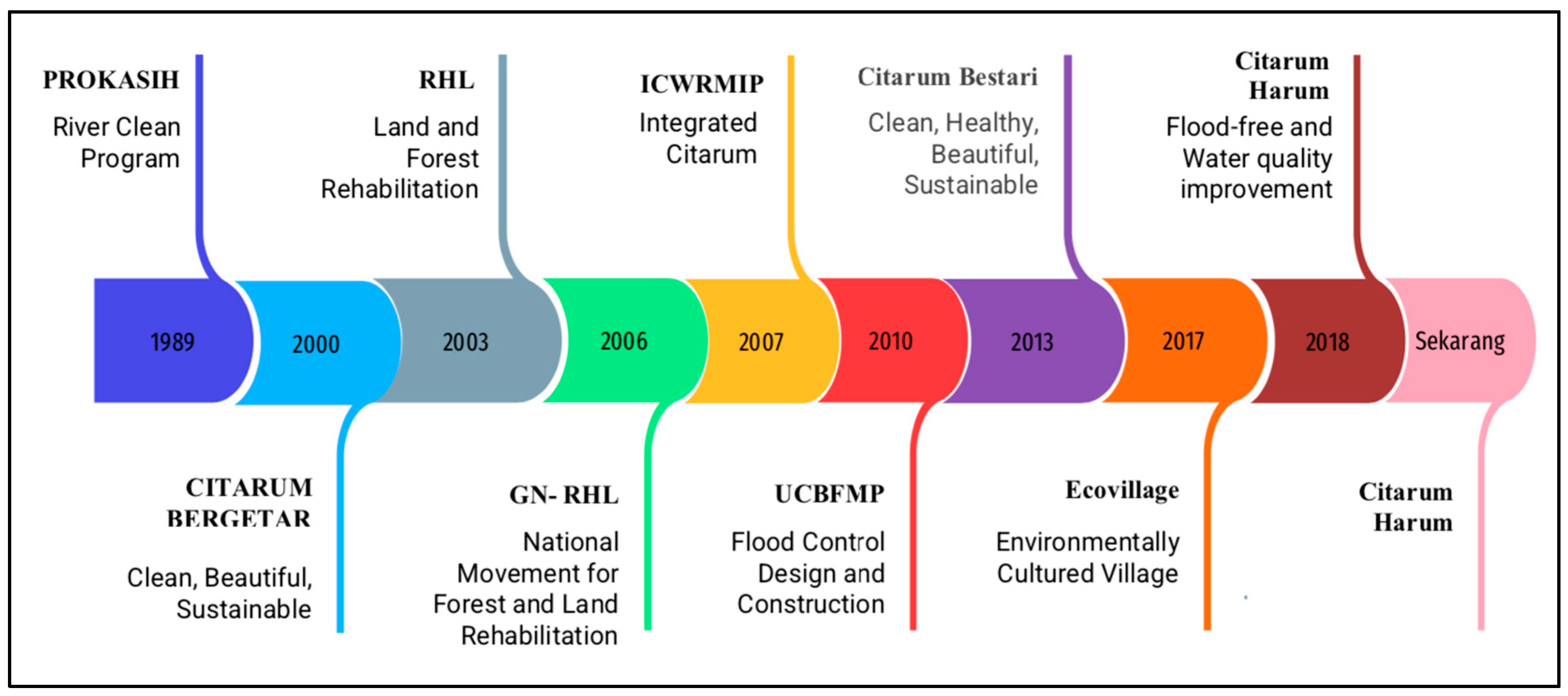

According to [

24], the Citarum River restoration program has been conducted since 1989 with the implementation of the Clean River Program (PROKASIH) launched by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (

Figure 1). PROKASIH aims to improve the Citarum River water quality through an industrial and domestic wastewater management scheme. The Provincial Government of West Java, from the year 2000 to 2003, established the Citarum Bergetar Program (clean, beautiful, sustainable). Furthermore, in 2003, the Forestry Agency of West Java enacted five priority policies to restore and maintain the sustainability of forest function through programs for the rehabilitation and conservation of forest resources. Since 2003, the Indonesian government has implemented the National Movement for Forest and Land Rehabilitation program (GN-RHL) to accelerate the implementation of Forest and Land Rehabilitation (RHL). It was established to foster the spirit of RHL as the nation’s moral movement toward accelerating the restoration of the existence and function of forests that improve the community’s welfare.

In 2007, the Indonesian government, through the Ministry of National Development Planning (Bappenas), developed the Integrated Citarum Water Resources Management Investment Program (ICWRMIP). The program’s surprising findings showed that many factory sewage pipes were hidden or underground and flowed directly into the Citarum River. Finally, from 2008 to 2011, the government launched and implemented the ICWRMIP program, abbreviated as Citarum Terpadu (Integrated Citarum). Moreover, in 2014, the Indonesian government established the Citarum Bestari (clean, healthy, beautiful, sustainable) movement to restore the Citarum River, which experienced declining water quality and increased waste volume. Unfortunately, the implementation of the Citarum Bestari program from 2013 to 2018 to overcome the Citarum River problem has failed to restore one of the dirtiest rivers in the world based on the World’s Dirtiest River report published by the International Herald Tribune on 5 December 2008, and by The Sun on 4 December 2009. In 2013, even the Green Cross, Switzerland listed the Citarum River as one of the world’s most toxic places, as The Richest reported.

The environmental issues that occur today, especially in West Java, can threaten the sustainability of living things in the world. It has become a significant concern that must be resolved collaboratively by the community and policymakers, including regional, national, and even international stakeholders. The DLH of West Java Province has socialized ecovillage activities in 12 cities/districts. The socialization started on 7 March 2017, in Bandung City, and ended on 30 March 2017, in Karawang Regency. The West Java Government continues to encourage the development of ecovillages, especially in areas traversed by four principal rivers: the Citarum, Cimanuk, Citanduy, and Ciliwung. From 2018 to now, this program has been called the Citarum Harum [

24].

The Citarum River is polluted by industrial, livestock, agricultural, and household waste; additionally, land conversion, critical land, poor community behavior, damage and depletion of water sources, and law enforcement difficulties are still major unresolved problems. This study aims to provide a valuable theoretical basis for studies related to ecovillage sustainability in the Upper Citarum watershed by first looking at the level of the sustainability of ecovillage development in the Upper Citarum watershed, West Java Province, Indonesia.

2. Literature Study

The notion of sustainable development traces its origins to the late 18th century when R. Malthus expressed apprehensions about land availability in England due to a burgeoning population in 1798. The inception of growth theory, the world’s first of its kind, was catalyzed by Thomas Robert Malthus (1798), his renowned population trap theory, and David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage. Fast-forward to 1972, when Meadow et al. published the groundbreaking book titled

The Limits to Growth. Meadow asserted that economic growth would face significant constraints due to the finite nature of natural resources, thereby rendering the sustained provision of goods and services from these resources unattainable in perpetuity. The awareness of sustainable development concerns emerged in 1987 with the publication of

Our Common Future by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) [

25]. This book triggered a novel agenda for economic development within the environmental context of sustainable development. The WCED defined sustainable development as an approach that seeks to fulfill the needs of the current generation while preserving the capacity of future generations to meet their own needs.

Conservation development, such as soil, water, crops, and genetic resources adhering to principles that prevent environmental harm, can be achieved through the application of suitable technology and practices that are socially and economically viable. As elucidated by the authors of [

26], Karl Marx, a prominent economist and political scientist, posited that “technological change engenders institutional change”. Development is a collaborative endeavor shared between the community, often called civil society, and the government. The government and civil society can collaborate to harness various potentials and resources to promote development rooted in local wisdom, particularly in rural areas.

In accordance with the opinion outlined in [

27], the prevailing development paradigm is undergoing a transformation, highlighting the significance of empowerment, characterized by a focus on people-centered development, development rooted in local resources, and institutional development. Despite the fact that the ultimate aim of development is enhancing living standards and creating a physically, mentally, and socially prosperous society, it is essential to underscore that the development approach employed should consistently prioritize processes over outcomes. The process-oriented approach is more inclined to steer the realization of human-centered development, as [

28] emphasized.

It has been posited that sustainable agricultural development comprises three key objectives: economic objectives centered on efficiency and growth, social objectives addressing ownership and equality, and ecological objectives targeting the preservation of natural resources and the environment. These three objectives are intrinsically interconnected, and realizing sustainable agricultural development hinges on attaining all three. Efficiency and growth within the agricultural sector can be fostered by promoting increased production, augmented farmer incomes, capital accumulation, and enhanced competitiveness. The pursuit of equitable resource ownership can be facilitated through policies addressing land reform and by enhancing farmers’ access to and control over agricultural resources, capital, technology, social welfare, and peace. In Indonesia, since the inception of the sustainable agricultural development process, various agricultural development systems have been implemented, encompassing both food and non-food commodities [

29].

Watershed management is designed to optimize economic advantages for humanity, benefiting local communities and the underprivileged, all while ensuring environmental sustainability and fostering participatory, self-reliant communities. To realize these objectives, comprehensive watershed management should encompass an integrated approach involving various stakeholders from the upstream to the downstream areas. The formulation of objectives for natural resource management within watersheds is conducted collaboratively, with sectoral programs aligned to promote sustainability within the watershed ecosystem. This approach is often called “One watershed, one plan, one management” [

30].

The author has conducted a literature review before conducting research over the past few years regarding ecovillages and sustainable watersheds or other similar configurations using the PRISMA framework. The search used English language articles in the Scopus database. The Scopus database is the largest peer-reviewed literature database [

31]. Article searches were carried out using the following keywords: “eco*” OR “eco-*” OR “village*” OR “village*” OR “ecovillage*” OR “ecovillages*” OR “sustainability*” OR “sustainable*” and others. We then added “sustainable ecovillage” OR “sustainable ecovillages” OR “ecovillage development” OR “watershed management” OR “sustainable community” OR “sustainable ecovillage development” OR “community base ecovillage” Based on the keywords, 1587 articles were obtained, and after checking for duplication, 999 articles were obtained; then, restrictions were obtained, and 340 articles were obtained. These articles were sorted more specifically in order to obtain 23 articles about ecovillages [

32].

Since it pays attention to “social relations, the particularities of place (culture), and the influence of technology and materiality” [

33] (p. 23), social practice theory has been useful in conceptualizing the emergence/consolidation of sustainable lifestyles in local-level initiatives, such as ecovillages [

34,

35,

36,

37].

The concept of an ecovillage is rooted in the principles of sustainable development and is underpinned by ecological findings. It involves implementing human settlement patterns or models that harmonize with their natural surroundings, resulting in ecovillages that manifest in diverse and adaptable forms tailored to the specific local natural and social environment. The conceptualization of ecovillages has been articulated on numerous occasions and in various manners [

38]. Real-world instances of ecovillage implementations can be observed across many diverse locations globally. The Global Ecovillage Network (GEN) is the international cooperative network connecting these endeavors. Ecovillages represent communal settlements dedicated to integrating sustainable practices as an intrinsic aspect of everyday life, with a central focus on fostering sustainable community development and environmental stewardship [

12].

Ecovillages, or intentional communities (ICs), can be considered “frontrunners” and spaces of experimentation in sustainability transformations [

39,

40]. Intentional communities refer to communal living arrangements more broadly, with sub-categories also including religious communities and communes [

41]. Ecovillages focus specifically on living sustainably and in a way that reduces their environmental impact [

12].

Ecovillages are human-built settlements that maintain a harmonious relationship between humans and nature, characterized by comprehensive features [

12]. Within these settlements, human interactions with the environment are consciously designed to be non-destructive, aiming to promote the well-being of both present and future generations. Ecovillages represent a collective endeavor where individuals reside in a physical framework, sharing a joint commitment to the sustainable use of their ecological surroundings. This way of life is deeply rooted in the profound understanding that all entities and living beings are interconnected.

From a philosophical standpoint, ecovillages are constructed based on various combinations of three fundamental principles: ecology, community, and spirituality [

42]. These principles are adaptable and applicable in both urban and rural settings, offering a framework for development, management, and problem-solving that addresses human needs while concurrently safeguarding the environment and enhancing the overall quality of life for all residents [

43].

The dimensions of ecovillage implementation according to Gilman and the Global Ecovillage Network (GEN) are presented in

Table 1.

The ecovillage (EV) movement has received considerable attention in the literature. For example, scholars have looked at how EVs, as a particular form of “intentional community” and lifestyle movement, have emerged and evolved over the years, and at various barriers experienced in the process of establishing and maintaining such initiatives, which have often failed. In fact, 80% of ecovillage communities have ceased to exist within two years of starting [

45].

The concept of a “spiritual community” can be applied to an ecovillage. It is crucial to elucidate the role of Gaia Trust, as well as its founders Ross and Hildur Jackson, in offering financial support and assistance for the establishment of the Global Ecovillage Network (GEN), whose international headquarters are situated in Findhorn. Gaia Trust, which was established by Ross and Hildur Jackson, has played a substantial role in funding and nurturing the development of the Global Ecovillage Network (GEN). GEN is an international organization that is committed to advocating sustainable living practices and the growth of ecovillages on a global scale. The organization operates with the objective of creating communities that not only prioritize ecological sustainability but also emphasize spiritual and holistic values [

46].

Findhorn, located in Scotland, provides comprehensive educational programs with a holistic approach. These programs encompass an annual ecovillage training program, permaculture workshops, courses focused on personal development, spirituality, and arts and crafts. Findhorn is an integral part of a substantial organic community-supported agricultural initiative and has its own local currency and banking system. It utilizes renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and biomass, and actively engages in waste recycling, including sewage treatment via a reed-bed living machine system. Findhorn houses numerous community-based enterprises and is actively developing a village comprising eco-sensitive houses. The community also hosts an award-winning reafforestation project called Trees for Life and advocates for a voluntary simplicity ethic [

46].

Notable thriving ecovillages include the Federation of Damanhur in Italy, which comprises 600 residents organized into different divisions, each equipped with supporting facilities and infrastructure, such as laboratories. These divisions are established based on the local potential of each, such as solar energy, education, organic meat production, and seed preservation. Similarly, Eco Truly Park in Peru, renowned for its exceptional mud houses, has devised innovative land cultivation methods not commonly practiced. In the United States, several ecovillages, such as “Dancing Rabbit” in Routledge, Missouri, have transformed old apartments into lush forests serving abundant food sources. Other examples include the Ithaca Ecovillage in New York, the Kailash Ecovillage in Portland, Oregon, and various ecovillages in different countries. Despite geographical diversity, similarities persist in the development of ecovillages across nations.

The concept of regional revitalization was first proposed in Japan [

47,

48], and similar concepts have been implemented in many countries and regions. One of them is Taiwan. Taiwan has made a lot of efforts in related fields in recent years and achieved certain results [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. Taomi Eco-Village [

58] is a village located in Puli Township, Nantou County, Taiwan, along the route to Sun Moon Lake. Before 1999, agricultural villages experienced a decline due to rapid industrialization in Taiwan and the earthquake in Taiwan on 21 September 1999, resulting in 70% of a small village being destroyed. Of the 369 houses, 168 houses were completely damaged, and 60 houses were partially damaged. Instead of being sad, residents used this crisis to not only carry out reconstruction but also change the image of the village. Ten years later, Taomi is proud to be an eco-friendly village, with the Paper Dome at its center. The Paper Dome originates from Japan and is an embodiment of love and mutual cooperation between the people of Taiwan and Japan who share the experience of community reconstruction in addition to being the heart of Taomi Eco-Village.

An examination of three ecovillages in the United States which was conducted offers valuable insights into how geographical location can impact the quality of external activities. In this regard, Dancing Rabbit, situated in a sparsely populated rural town (deemed a more radical project by Boyer), primarily disseminated its practices through replication. Conversely, Los Angeles Ecovillage (LAEV), established within an urban center (representing a more integrated urban-rural project), expanded the adoption of ecovillage practices through heightened activity in the ecovillage domain. Ecovillage Ithaca (EVI), positioned in the suburbs (classified as an “intermediary” project), emerged as the sole effective one among the three [

59].

According to the authors, suburban areas have historically provided fertile ground for innovative forms of development. Consequently, ecovillages and similar communities incorporating agricultural elements into their environments can be experimental models for innovative land-use practices. These initiatives often support small-scale agricultural endeavors in regions where costs would otherwise prohibit such activities, thereby mitigating tensions between urban and rural zones [

60].

However, Boyer emphasized that the “intermediary” status of EVI is also closely associated with a “balanced” approach. These ecovillages challenge certain social conventions, endeavoring to effect change without overtly resisting them. Consequently, projects embodying this “intermediary” character are often preferred as they bridge rural and mainstream urban society [

59,

61]. Nonetheless, it is essential to recognize that this characteristic does not solely hinge on geographical location but involves a more intricate set of considerations. Furthermore, it is worth noting that rural locales do not necessarily equate to isolation in an era of enhanced communication, as accessibility and transportation have improved in many regions. Refs. [

62,

63] believed that ecologically sustainable settlements, in relation to spatial utilization and land use, encompass endeavors aimed at prudent space utilization and the preservation of green open spaces. Another facet involves fostering environmentally friendly behavior, which, according to [

64,

65], constitutes a vital component in realizing ecovillages, including practices such as providing open spaces, responsible management of clean water, rainwater treatment, adopting green technology, judicious use of energy resources, and reforestation.

3. Materials and Methods

There need to be more comprehensive studies on the ecovillage in Indonesia, especially on the sustainable ecovillage development in the upstream Citarum watershed area of West Java province. Most studies only focus on the three dimensions of sustainable development: social, economic, and ecological. Ecovillage development in various developing countries has good sustainability. Therefore, this study aims to determine the sustainability level of ecovillage development in ecological, economic, social, and cultural aspects by explaining the most sensitive attributes that affect ecovillage sustainability in the Upper Citarum watershed of West Java Province. The results of this study provide an empirical reference for the conditions and efforts that improve the sustainability level of ecovillage development in the Upper Citarum watershed of West Java Province. The practical implication of this study can be the basis of sustainable ecovillage development in various development areas. It can also be used as direction for policy consideration in developing sustainable ecovillages by understanding the various dimensions and considerations of the sustainable ecovillage model to be developed.

Many communities have been formed worldwide based on the principles of living in an environmentally, socially, economically, and spiritually sustainable way. For example, the Global Ecovillage Network is a community that strives for a lifestyle that is “a model of sustainable living and an example of how actions can be taken to protect the environment” [

44]. These goals have emerged in response to the growing unsustainability of human activities and their impact on Earth’s ecological systems [

66,

67,

68,

69].

Studies on intentional communities are more likely to be social science-based by reviewing all the academic literature and aspects of intentional communities [

70]. From the identification of 59 studies, 49 used a social science approach, and only 10 used a natural science approach. This categorization was determined based on the focus of the studies. Of the 10 studies that used a natural science approach, only four addressed ecological sustainability issues by quantifying EF or energy consumption. Wagner found that studies directly comparing ecovillage communities with housing or other forms are rare. Wagner’s paper was designed to provide an overview, so his research results have not yet been presented and discussed. Wagner realized his paper might be imperfect. Thus, a more comprehensive review of his research is needed.

Ecovillages are very heterogeneous, and describing all cases in one model is impossible [

71]. They have diverse origins ranging from the purpose of the implementation to the reasons for formation, including the ideals of self-sufficiency and spiritual approaches, such as in monasteries, ashrams, and the Gandhian movement; environmental, pacifist, feminist, and alternative education movements of the 1960s and 1970s; and movements such as back-to-the-land cohousing in capitalist countries, participatory development, and technology appropriation in developing countries [

72,

73].

The concept of ecovillages did not emerge spontaneously but can be traced back to the 1991 report authored by activists Robert and Diane Gilman. This report marked the inception of the widespread use of the term. In their work, the Gilmans delineated settlements from various parts of the world that served as inspirational models for communities seeking to transition into sustainable societies, to coin the term“ecovillages” [

71]. Subsequently, numerous new communities have arisen, adhering to the principles of ecovillages, particularly in the northern hemisphere and among expatriate communities in the southern hemisphere [

71]. Concurrently, some pre-existing communities also began identifying themselves as ecovillages [

70]. For instance, the Findhorn development in Scotland, often referred to as the “mother of all ecovillages” [

73], originally functioned as an intentional community with a strong focus on spiritual development [

45]. The development of ecovillages has proven successful in certain countries.

The research was conducted within the Upper Citarum watershed of West Java Province, Indonesia, employing a quantitative analysis design. The research applied the case study method, the sample selection technique using cluster random sampling with the data collection performed through in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, and documentation studies. A case study constitutes a form of descriptive research that provides a comprehensive description of the background, nature, and characteristics, which can be extrapolated to broader contexts [

74].

This research was conducted in the Upper Citarum watershed which consists of 5 sub-districts. Namely Kertasari District, Pacet District, Ibun District, Paseh District, and Majalaya District. Based on BPS, in 2013, in the upper reaches of the Citarum watershed, there were 54 villages in 5 sub-districts. A total of 39 villages are categorized as agricultural villages and 15 villages are urban/industrial villages. This research was conducted in 11 villages in the Agrarian Village category. These 11 villages represent 5 sub-districts in the Upper Citarum watershed, West Java Province, Indonesia.

Respondents are participants/members who are members of the ecovillage community. This community consists of 20 people per village. Respondents from 11 villages totaled 207 people, because 13 community members have left the village/work outside the village. The research was conducted in 11 ecovillages developed in the Upper Citarum watershed, as seen in

Table 2.

The research was performed from September 2021 to January 2022. The data of this study included statements and descriptions taken, literature reviews, field observations, interviews, and questionnaires about developing ecovillages within the Upper Citarum watershed of the West Java Province. The data and its respective sources were primary data from the observations conducted by closely observing activities within and around the designated location. This observational approach entailed active and passive participatory methods, wherein the researchers physically visited the location but refrained from direct involvement in the community’s activities, opting instead for meticulous observation. Furthermore, secondary data was obtained from a comprehensive literature review covering various regional, national, and international sources. This process involved sourcing data from electronic platforms, books, academic journals, and other reputable resources. Secondary data may manifest in various forms, including legal statutes, regulations, prior research findings, or scholarly articles, all of which enrich the analysis and facilitate the formulation of solutions. Data was collected from expert respondents by administering an ordinal questionnaire meticulously tailored to align with the specific attributes of each indicator. Respondents were required to rate these indicators on a scale ranging from 1 (indicative of poor performance) to 4 (indicative of excellent performance).

Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) is a valuable tool for assessing the degree of sustainability. MDS is a multivariate statistical analysis method employed to determine the positioning of an object about its similarity or dissimilarity to other objects using several variables [

75]. As articulated by the authors of [

76], MDS is a data analysis technique that visually represents data in geometric forms predicated on the concepts of similarity or dissimilarity, utilizing the Euclidean distance metric.

Figure 2 illustrates the utilization of this analytical approach across multiple stages.

MDS was conducted using the following steps:

Identifying and determining the sustainability indicators for ecovillages within the Upper Citarum watershed of West Java Province. This process began by comprehensively examining the prevailing conditions and phenomena within the region, informed by primary and secondary data collected in the field. The identified indicators comprised four distinct dimensions: ecological, economic, social, and cultural. Each dimension is subsequently evaluated through the measurement of its respective attributes.

According to Gilman, an ecovillage represents a departure from traditional settlements, embodying a phenomenon rooted in post-industrial society. However, a more pragmatic interpretation, proposed by Hollick and Connelly, characterizes an ecovillage as a community comprising several hundred individuals that not only addresses its residents’ material, economic, social, and emotional needs but also maintains harmony with its natural surroundings. Notably, this definition assigns significant importance to fulfilling the spiritual needs of inhabitants, although it is observed that ecovillagers often hold divergent religious beliefs. Consequently, spirituality should not be regarded as one of the core tenets of this concept [

77].

The assessment of each attribute was conducted using an ordinal scale that aligns with the sustainability criteria established for each dimension. Expert respondents employed scientific judgment to evaluate each attribute, and the ordinal assessments were provided on a scale ranging from 0 to 2 or 0 to 3, tailored to reflect the specific characteristics of the attribute, with 0 signifying the lowest level of assessment and 3 representing the highest.

Table 3 presents the details regarding the study variables for each dimension.

Table 3.

Description of Variable.

Table 3.

Description of Variable.

Variable

Dimension | Attribute | Score | Description |

|---|

| Ecology | Garbage and solid waste management | 1, 2, 3 | 1 = Poor

2 = Average

3 = Excellent |

| Spring Protection |

| Change in vegetation cover |

| Conservation measures |

| Agricultural and Domestic waste utilization |

| Agricultural waste disposal |

| Fertilization |

| Land utilization |

| Land use suitability |

| Economy | Ability to strengthen economic development | 1, 2, 3 | 1 = Poor

2 = Average

3 = Excellent |

| Productive business development |

| Types of creative economy businesses |

| Youth seek employment outside the village |

| Community support for business creation |

| Community support for product sales |

| Perception of environmental changes |

| Social | Facilities and infrastructure availability | 1, 2, 3 | 1 = Poor

2 = Average

3 = Excellent |

| Extension frequency |

| Frequency of Conflicts |

| Community Understanding |

| Community Commitment |

| Support from village officials |

| Community Organization |

| Community participation |

| Frequency of meetings |

| Cultural | Local Social Processes | 1, 2, 3 | 1 = Poor

2 = Average

3 = Excellent |

| Local Resources |

| Local skills |

| Local culture |

| Local knowledge |

Calculating the sustainability index and analyzing the sustainability status. According to [

79], The estimated score of each dimension was expressed from 0 (poor) 0% to 100 (Excellent). The sustainability index is the value of each dimension describing the level of sustainability (

Table 4).

Table 4.

The Category of Sustainability Index.

Table 4.

The Category of Sustainability Index.

| Index Score (%) | Category |

|---|

| 0–25 | Very poor (Unsustainable) |

| 25–50 | Poor (Poorly sustainable) |

| 50–75 | Fair (Fairly Sustainable) |

| 75–100 | Excellent (Highly sustainable) |

Using the Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) method, the sustainability points’ spatial representation can be effectively visualized along horizontal and vertical axes. Through rotation, the position of each point can be visualized at the horizontal axis, corresponding to a sustainability index score ranging from 0% (indicative of very poor sustainability) to 100% (indicative of excellent sustainability). Furthermore, this visualization enables the simultaneous representation of the sustainability index scores for each dimension as a kite diagram. The symmetry exhibited in the kite diagram is contingent upon the sustainability index values of each dimension (ecological, economic, social, and cultural). Additionally, the sustainability index values of each dimension can be conveniently displayed on the diagram, facilitating a more straightforward assessment of their respective sustainability statuses. It is worth noting that a more enormous Root Mean Square (RMS) indicates a heightened sensitivity of the indicator to sustainability considerations.

The next step is to examine the most sensitive attributes using leverage analysis. This analysis was carried out to determine the key indicators contributing to the sustainability index; sensitivity analysis was undertaken by examining the Root Mean Square (RMS) change on the x-axis.

Monte Carlo analysis is a critical tool for conducting uncertainty analysis, specifically in estimating the influence of random errors within the analysis process while maintaining a 95% confidence interval. In this context, Monte Carlo analysis was employed as a simulation technique to assess the repercussions of random errors across all dimensions. In this study, Monte Carlo analysis was conducted using the “scatter plot” method, visually depicting the procedural steps involved in evaluating each dimension.

4. Results and Discussion

Figure 3 presents the position analysis of the sustainability index of the ecological dimension, economic dimension, social dimension, and cultural dimension in the Upper Citarum watershed of West Java.

Figure 3 illustrates the sustainability index values for the ecovillage in the Upper Citarum watershed of West Java Province. Within this context, it is observed that the social dimension exhibits the lowest sustainability index value (41.23), signifying the least sustainable level among the ecological, economic, social, and cultural dimensions. The economic dimension follows closely, with a sustainability index of 41.82, followed by the ecological dimension, which demonstrates a sustainability index of 48.72. Conversely, the cultural dimension boasts the highest sustainability index value at 65.28. Based on the sustainability index positions for each dimension, it becomes apparent that implementing ecovillages in the Upper Citarum watershed is positioned at the “poorly sustainable” level concerning the ecological, economic, and social dimensions. In contrast, the cultural dimension occupies a “poorly sustainable” status but is closer to the “fairly sustainable” range. It is important to note that these findings may be influenced by the data collection period coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in limited community activities within the Upper Citarum watershed, West Java Province.

Figure 4 illustrates the calculation of the most sensitive attribute values within the four dimensions of ecovillage sustainability.

4.1. Ecological Dimension

The analysis of the RAPVIL framework reveals that, for the ecological dimension, the average development index value across 11 villages is 48.72. In light of the sustainability index position within the ecological dimension, it is evident that the ecovillage implementation in the Upper Citarum watershed is categorized as being at the “poorly sustainable” level. The ecological and environmental dimension holds particular significance as it plays a pivotal role in determining the equilibrium between natural resource utilization and the provision of environmental services. In this regard, specific environmental attributes were meticulously chosen to elucidate the impact of natural resource utilization and environmental practices on sustainability within the ecological dimension.

The analysis of the ecological dimension’s sustainability level in ecovillage development encompasses nine key attributes: waste and garbage management, water source protection, vegetation cover change, conservation measures, agricultural and domestic waste utilization, agricultural waste disposal, fertilization, land use, and suitability.

Figure 4 provides insights into the sensitivity of these attributes in influencing the sustainability of ecovillage development within the Upper Citarum watershed of West Java Province. These attributes are ranked from the most sensitive to the least sensitive based on their Root Mean Square (RMS) values. Among these attributes, disposal of agricultural waste stands out as the most sensitive factor, as indicated by its high RMS value (2.19). Protection of springs, fertilization, vegetation cover change, and agricultural and domestic waste utilization also exhibit significant sensitivity, with an RMS value of 1.99, 1.62, 1.42, and 1.18, respectively. Meanwhile, land use suitability, land utilization, solid waste management, and conservation measures demonstrate progressively lower sensitivity, culminating with conservation measures registering a minor sensitivity (RMS = 0.83, 0.64, 0.42, and 0.01, respectively).

These findings shed light on the challenges surrounding the management of agricultural waste, particularly in terms of disposal, where some farmers have yet to adopt effective practices. Notably, using springs for irrigation in the Upper Drawati area, alongside rainwater reliance, adds complexity to the ecological dimension. Moreover, the impact of fertilization on agricultural waste warrants careful consideration, as chemical fertilizers may result in pollution when agricultural waste is discharged into rivers. In the context of agroecology-based food production, a comprehensive approach is advocated. This approach encompasses practices like biodiversity preservation through polyculture, agroforestry, and economic water use like drip irrigation. Additionally, techniques aimed at preserving and enhancing soil fertility, such as using organic fertilizers and mulch, are encouraged, emphasizing the avoidance of chemical fertilizers and agricultural pesticides [

80].

Changes in vegetation cover within the ecovillage area are declining, and the rate of agricultural-to-non-agricultural land conversion is notably high in several development villages and their adjacent regions. This land conversion serves various purposes, including residential development, public facilities, and infrastructure, such as roads and public buildings. Despite some community efforts, agricultural and domestic waste utilization remains limited. Although specific communities have taken steps like constructing septic tanks and segregating organic and non-organic waste for yard-based fertilizer production, comprehensive waste management practices are not widespread.

Ecovillages are committed to energy-efficient housing [

81] and employ “low-impact construction” techniques, including bioconstruction methods. Additionally, ecovillages tend to minimize reliance on polluting transportation [

73] and adopt waste reduction strategies that involve recycling and processing residues, especially organic waste, which is transformed into organic fertilizer through composting. Most ecovillages prioritize local production, particularly for food and renewable energy sources [

73]. However, it is essential to note that not all development villages have fully harnessed their local product potential. There are notable gaps regarding land suitability and utilization in the development villages. Some farmers cultivate land with steep slopes, while others allocate it for housing.

Ecovillage development’s emphasis on ecological aspects is prominently reflected in spatial design principles [

82]. These designs are meticulously planned to preserve green spaces, optimize energy efficiency, and efficiently use space and materials [

16]. Such objectives are predominantly realized through cooperation and resource-sharing practices [

73], including the sharing of land, buildings, resources, equipment, and tools, and the cultivation of consumption patterns that prioritize reduced consumption levels within the community [

41].

Nevertheless, it is essential to recognize that, in certain villages, spatial layout still hinges on the preferences of individual landowners. Exceptionally, in cases where some farmers work on forestry land or leased land, formal and informal agreements are typically established between the landowner and the tenant. The current trajectory of ecovillage development has witnessed a proliferation of instances where ownership of land and buildings is collectively shared. However, it is imperative to acknowledge that this practice is not universal, as some ecovillages maintain a more traditional landowner–tenant relationship [

73]. Ultimately, this divergence reflects a return to a conventional order characterized by the predominance of capitalistic principles.

To understand the essence of ecological settlements, it is imperative to interpret the term “eco-settlement”, or ecovillage, initially coined by R. Gilman in 1991 in a report issued by the Institute of Context for the Earth Trust. Here, an eco-settlement is delineated as “Human-scale, full-featured settlements in which human activities are integrated in a non-harmful/polluting manner that is destructive to nature”, all while fostering healthy human development and ensuring sustainable continuation into the future [

83]. In a case study conducted in Denmark titled “Ecovillages: What is the Way to Achieve Environmental Sustainability?” (Aalborg University, Denmark), it is articulated that, according to Gilman, ecovillages represent a departure from traditional settlements and manifest as a phenomenon specific to post-industrial societies. However, a more pragmatic conceptualization of this notion is offered by Holick and Connelly, characterizing ecovillages as “communities comprising several hundred people that satisfy the material, economic, social, emotional, cultural, and spiritual needs of their residents while coexisting harmoniously with the natural environment.”

While waste and solid waste management must be effectively administered across all eco-villages, the reality is that only a limited number of villages actively engage in waste management practices and possess rudimentary waste banks and sorting facilities. Conservation measures emerge as the least sensitive attribute within this ecological dimension, primarily because conservation activities are typically addressed comprehensively within other attribute categories.

4.2. Economical Dimension

The economic dimension plays a crucial role in assessing the sustainability of ecovillage development within the Upper Citarum watershed of West Java Province, Indonesia. Ecovillages adopt selective local consumption and production practices to achieve economic objectives, such as optimizing resource utilization, reducing costs, fostering alternative employment relationships, and facilitating non-conventional exchanges of products and services. Collaboration and cooperation are integral components of the economic framework in ecovillages, often taking the form of economic communalism [

81], though this varies.

The results of the RAPVIL analysis, illustrated in

Figure 3, provide insights into the sustainability of the economic dimension. The horizontal axis represents the economic dimension’s rating, ranging from very poor (0%) to excellent (100%), while the vertical axis displays diverse scores for the economic attributes.

Figure 3 shows that the average development index value for the economic dimension across the 11 villages is 41.82. The positioning of the sustainability index within the economic dimension indicates that ecovillage implementation in the Upper Citarum watershed currently falls within the “poorly sustainable” category. In assessing ecovillage sustainability within the economic dimension, seven essential attributes are considered: economic improvement capability, productive business development, creative economy business type, youth working outside the village, support for business creation, support for product sales, and perception of environmental change.

As depicted in

Figure 4, among the seven attributes in the economic dimension, their sensitivity levels vary, ranging from the lowest to the highest. These attributes and their respective Root Mean Square (RMS) values are as follows: perception of environmental change (0.29), ability to strengthen economic growth (0.46); youth seeking employment outside the village (1.16); productive business development (1.77); community support for product sales (2.40); community support for business creation (3.12); and types of creative economic businesses (4.66).

Developing creative economy businesses serves the purpose of increasing income in the eco-villages. In particular development areas, if activities do not yield profits, they become highly vulnerable and have limited sustainability. The attribute of community support for business creation is intricately linked to support for product sales. The role of product sales is sensitive, as business and product creation hinge on demand and supply within the community. To boost income, generating products that can be offered is imperative. However, in development villages with nearly identical potential, there tends to be a tendency to produce the same product. Consequently, marketing becomes challenging when the product creation process succeeds due to a lack of market access. Therefore, assistance in business creation and product sales, including facilitating market access, is vital. This measure can be achieved by transforming a village into a potential tourist destination, creating economic growth and sustainability opportunities.

The attribute of productive business development in the development village is ideally pursued collaboratively with other community members to enhance collective bargaining power. In contrast, the number of youths seeking employment outside the village is interconnected with various other attributes, as young individuals often perceive a lack of welfare guarantees within their home village. Nevertheless, fostering economic development in the village and generating higher income and welfare makes it feasible to attract youth and encourage their active participation in village development.

The attributes related to enhancing the economic growth and the perception of environmental change exhibit the lowest sensitivity levels. This finding can be attributed to the centripetal and centrifugal forces exerted by the village and external factors. Limited capital within the village community hinders the effective management of its potential and local wisdom, necessitating continuous training and skill development in village development initiatives. Ref. [

83] highlighted the significance of proper financial planning, as land prices and limited financing options pose significant constraints, leading to the failure of many communities. Economic relations within communities may lead to conflicts, often stemming from varying community interpretations of individual property rights. Ref. [

73] further reported that unresolved financial issues have been the downfall of numerous community initiatives.

Sustainable ecovillage development activities within the Upper Citarum watershed, particularly in the economic dimension, currently operate at a “poorly sustainable” level. One contributing factor is the lack of interconnectedness among economic activities within ecovillage communities. These communities often engage in economic activities independently of each other. For instance, in Drawati Village, where agricultural activities are the primary focus, there is a lack of integration among farmers. This lack of integration spans various aspects, including the types of crops planted, agricultural cultivation practices, maintenance, and marketing efforts, all of which are typically undertaken individually by farmers. While some farmers have joined farmer groups, the full potential of these groups has not been harnessed to optimize farming practices. Consequently, fostering connectivity among farmers is essential to enhance the effectiveness of economic activities, ultimately leading to increased productivity and higher income levels.

Generally, members of ecovillages strive to engage in activities aligned with their values and aspirations, such as ecological agriculture, alternative education, renewable energy initiatives, ecological construction, art, ecotourism, and the practice of communication and self-management techniques. Although these endeavors may yield lower incomes, they are consistent with the findings of research conducted by the authors of the reference from [

84]. According to [

73], in affluent countries, many ecovillages comfortably maintain their lifestyles with incomes below the poverty line. However, this does not imply a scenario of impoverishment; instead, it reflects the fulfillment and contentment they derive from their chosen activities.

4.3. Social Dimension

The social dimension is pivotal in achieving ecovillage sustainability within the Upper Citarum watershed. The social aspect is a critical component of sustainable development that has the potential to contribute significantly to rural development and poverty alleviation [

85]. Furthermore, communal cultural practices are prevalent and foster social cohesion within communities [

73]. Observations by the authors of the reference from [

86] revealed the strong connection between the high quality of life experienced by ecovillage members and the support derived from communal living. This support often manifests as intergenerational integration, as [

73,

82] noted. Additionally, Ref. [

73] observed a tendency in many ecovillages to move away from the nuclear family-centric model, with the community emerging as the primary social structure.

The results from the RAPVIL analysis (

Figure 3) illustrate the sustainability of the social dimension. The horizontal axis indicates the spectrum of sustainability from very poor (0%) to excellent (100%) for the social dimension, while the vertical axis displays the varying scores related to social attributes.

Figure 3 reveals that the average development index value for the social dimension across the 11 villages is 41.23. Based on the positioning of the social dimension sustainability index, as indicated in

Figure 3, it is evident that ecovillage implementation within the Upper Citarum watershed currently operates at a “poorly sustainable” level. Nine attributes were employed in the analysis to assess the sustainability level of ecovillages in the social dimension: (1) the availability of facilities and infrastructure, (2) the frequency of counseling, (3) the frequency of conflict, (4) community understanding, (5) community commitment, (6) support from village officials, (7) community institutions, (8) community participation, and (9) the frequency of meetings.

Figure 4 provides insights into the sensitivity of these nine attributes within the social dimension, ranging from the least to the most sensitive. Support from village officials exhibits an RMS value of 1.32, followed by community commitment with an RMS value of 1.52. The availability of facilities and infrastructure carries an RMS value of 1.80, community institutions have an RMS value of 1.91, and community participation stands at an RMS value of 1.92. On the other hand, community understanding registers an RMS value of 4.73, the frequency of meetings demonstrates an RMS value of 4.84, and the frequency of counseling holds an RMS value of 4.98. Lastly, the attribute with the highest sensitivity is the frequency of conflict, with an RMS value of 6.21.

Notably, the attributes of the frequency of conflict and the frequency of counseling are the two most sensitive attributes. This phenomenon arises due to the diverse backgrounds from which the ecovillage community members originate, each with unique limitations. Despite these challenges, the ecovillage community is intentionally formed to encourage sharing and collaboration among individuals to create an ecovillage. Ecovillages promote robust social interactions facilitated by shared spaces within the community [

16,

60,

73,

82,

87] and various social gatherings [

16,

82], such as communal food sharing [

16,

36] and collective labor activities, including food production and others [

36,

60].

Conflicts within ecovillages are often related to various activities, including conflicts of interest and ownership. To address these potential ownership conflicts, ref. [

88] has outlined several effective measures observed in ecovillages, including holding land ownership under a Foundation or Non-Profit Organization, allowing individuals to disengage from the community without incurring economic loss, and allowing each community member to maintain private ownership or integrate their property into community assets. Some ecovillages even adopt a more autonomous ownership structure by subdividing land into multiple parcels. However, this approach may risk diminishing community bonds, resembling something closer to an “eco-condominium”, where individual land parcels are subject to conventional market buying and selling regulations, potentially introducing capitalist dynamics.

Regarding counseling frequency, it is primarily implemented to preempt conflicts. A higher frequency of counseling is intended to foster robust communication within the ecovillage community, enabling each individual to express their desires and align them with the overarching ecovillage objectives, ultimately ensuring that shared ideals represent the collective vision of every member.

The attributes of community understanding and participation play a vital role in ecovillage development within the Upper Citarum watershed of West Java Province. These attributes gauge the extent of community involvement in the ecovillage’s planning, execution, and evaluation phases, fostering a sense of unity among community members. However, such close-knit social interactions can also lead to challenges. The study presented in the reference from [

82] revealed that ecovillage communities expressed frustration over unmet expectations of a simpler life, as the conveniences of communal living sometimes came with complexities associated with social obligations. This issue arises because community members come from diverse backgrounds with varying ideals and values. Refs. [

80,

89] argued that ecovillage residents must juggle rural and urban lifestyles, a challenging but characteristic aspect of communal living.

Additionally, community institutions and the availability of infrastructure, although not highly sensitive attributes, are critical factors in the sustainability of an ecovillage. Development initiatives rely on the support of existing community institutions, involving numerous community members in social development activities. Similarly, the availability and proper utilization of facilities and infrastructure are essential to ensure that activities can be carried out effectively.

Community institutions are interconnected with local, regional, and national government officials, underscoring the importance of these networks in ecovillage settings. Another crucial attribute is community commitment and support from village or government officials. In ecovillage communities, the primary implementer plays a significant role and is entrusted by the community with decision-making processes [

90]. Decision-making in ecovillages typically follows a participatory approach involving all stakeholders to achieve consensus and mutual agreement [

16]. This consensus-building process entails negotiation, where each party can voice their concerns, focusing on accommodating various demands to ensure that everyone feels their input has been considered. Decisions are reached through mutual agreement [

91].

It is important to note that consensus does not require complete agreement on every issue; instead, it aims to ensure that everyone is sufficiently satisfied with the group’s decisions and willing to support them without vetoing them [

73]. Equality is fundamental in group decision-making processes and community discussions [

16,

73]. However, the effectiveness of horizontal consensus largely hinges on shared ownership of the decision-making structure [

88,

90]. When the structure resembles a landlord–tenant relationship, an evident power imbalance emerges, as noted in [

84]. Even in cases of shared land ownership, hierarchies may exist [

41,

90,

92], with specific individuals assuming more active roles within the community due to their sense of ownership [

90], potentially leading to gender-based hierarchies [

84].

4.4. Cultural Dimension

The prevailing sustainability model often overlooks its cultural dimension, possibly due to the abstract nature of culture. Nevertheless, culture is a crucial foundation upon which all other dimensions are contextualized and articulated, encompassing our values, beliefs, principles, and worldview. It can be argued that culture becomes “materialized” in practice. Ref. [

73] posited that socio-material and conscious transformations are intricately intertwined. This notion does not imply that large-scale cultural shifts must precede concrete actions; the relationship between the two is dialectical, with existing practices capable of shaping and disseminating new cultures.

The analysis results using RAPVIL reveal the sustainability of the cultural dimension, as depicted in

Figure 3. The horizontal axis ranges from very poor (0%) to excellent (100%) sustainability for the cultural dimension, while the vertical axis displays varying scores on the social attributes.

Figure 3 illustrates the average development index value for the cultural dimension in the 11 villages as 65.28. Based on the position of the social dimension sustainability index (

Figure 3), it is evident that ecovillage implementation in the Upper Citarum watershed reaches a “fairly sustainable” level. This underscores the paramount role of the cultural dimension in ecovillage development.

Indonesia, known as “Bhineka Tunggal Ika”, signifies the diversity within the country, encompassing variations in ethnicity, religion, norms, and customs. The village communities in the development area have long adhered to established rules, norms, and customs. However, the cultural diversity present in Indonesia poses a challenge to achieving ecovillage sustainability. This issue pertains to differences in gender, age, occupation, and development areas, closely linked to variances in the local potential of ecovillage development regions. Some regions possess indigenous knowledge and a community committed to preserving existing cultural practices, making community-based ecovillage development more feasible.

In the assessment of the cultural dimension’s sustainability level in the development of ecovillages within the Upper Citarum watershed of West Java Province, five attributes are considered: (1) local cultural processes, (2) local wisdom, (3) local skills, (4) local culture, and (5) local knowledge.

Figure 4 reveals that, among these five attributes, within the cultural dimension, the highest to lowest sensitivity as indicated by RMS values is as follows: local culture (6.99); local wisdom (6.68); local skills (1.16); local knowledge (1.40); and local cultural processes (0.09). Local culture and wisdom emerge as the most sensitive attributes within the development village, underscoring their paramount importance in ecovillage development. In this context, cultural factors play a pivotal role. Ref. [

93] contended that the ecovillage movement is defined by a profound commitment to, and a critical examination of, discontent with contemporary Western capitalist culture, particularly its patterns of consumerism and individualism [

82,

84]. The movement’s practice of sharing is intricately tied to this critique and is considered by the authors of the reference from [

73] to be a fundamental tenet of ecovillage living.

The ecovillages’ agricultural endeavors are directly aligned with political ideals, such as food sovereignty, social justice, economic development rooted in reciprocity, the entitlement to welfare, and the autonomy to manage one’s work hours, all of which reflect intricate forms of resistance to the dominant culture [

36]. However, it should be noted that “This definition places great emphasis on human spiritual needs and other facts, but in general, most ecovillages do not share the same religious beliefs and often have different religions to other community members. Therefore, spirituality should not be considered one of the concept’s core principles” [

77].

In sustainable ecovillage development, attributes like local skills, local knowledge, and local cultural processes take on a supportive role within the cultural dimension. Local skills support every activity undertaken within the development village, while local knowledge represents a wellspring of growth potential. Both local skills and knowledge enhance competitiveness in ecovillage development. Ref. [

16] argued that the most significant challenge that ecovillages must confront is a cultural one intertwined with the prevailing values and beliefs of the broader world.

Cultural sustainability is concerned with sustainable development (or desirability) with respect to the maintenance of cultural beliefs and practices, the preservation of heritage, and the preservation of culture as its own entity, and addresses the question of whether certain cultures will continue to exist in the future, reference from [

94]. From cultural heritage to the cultural and creative industries, culture is a supporting and driving factor of the economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development. At the same time, how to let it gradually form its own characteristics and advantages in the process of depicting cultural connotations is also a topic that needs to be researched. This study combines the dimensions of Gilman’s and GEN’s ecovillage, namely the ecological dimension, social dimension, economic dimension, and cultural dimension, because the cultural dimension is also related to the spirituality of the community.

4.5. Multidimensional Scalling

RapVill analysis employed the MDS method with Monte Carlo analysis and multidimensional leverage analysis on each dimension in sustainable ecovillage development, including ecological, economic, social, and cultural dimensions.

Table 5 presents the analysis produced by the statistical parameters.

The multidimensional analysis using the RAPVIL technique, employing the multidimensional scaling (MDS) method, yielded an index value of 49.76 for ecovillage development in the Upper Citarum watershed of West Java Province. The S-Stress value falls within the range of 0.15–0.19, while the R2 value is between 0.91 and 0.95. This outcome, derived from four dimensions (ecological, economic, social, and cultural aspects), indicates that ecovillage sustainability in the Upper Citarum watershed of West Java Province is currently at a “poorly sustainable” level. The inconsistency of the capitalist approach to sustainability becomes apparent in its compartmentalized and unequal treatment of the various sustainability dimensions. In the prevailing model, sustainability theoretically comprises economic, social, and ecological dimensions, which should ideally be addressed and worked on in an integrated manner.

However, in practice, the social dimension is often overlooked, and ecological issues, despite being constantly “raised”, remain challenging to tackle, with the adverse effects of pollution being impossible to ignore. What typically transpires is the dominance of the economic dimension to the detriment of all others. It is worth noting that political and cultural aspects, theoretically part of the social dimension, are frequently obscured, exacerbating the sustainability debate. The dimensions of ecovillage development are inherently intertwined, with each dimension enhancing the sustainability of the whole. As previously reported from [

95], ecovillages typically seek to influence their communities by exemplifying a more sustainable way of life [

59,

73,

81,

84,

96,

97].

Hence, despite emphasizing ecological sustainability, many authors contend that this aspect alone cannot characterize an ecovillage.

Figure 5 shows that the Sustainability Index is multidimensional, revealing varying values across different dimensions. Among these dimensions, the cultural dimension stands out with the highest RMS (65.25).

Figure 5 visually represents the multidimensional sustainability value for ecovillage development in the Upper Citarum watershed of West Java Province, Indonesia, which falls within the “poorly sustainable” category with a total multidimensional value of 49.76. Further examination of

Figure 5 confirms that the multidimensional sustainability index registers at 49.76 for the sustainability level of ecovillage development in the Upper Citarum watershed. These dimensions comprise ecological, economic, social, and cultural aspects. Notably, the cultural dimension achieves the highest sustainability value at 65.28, while the social dimension lags with a sustainability value of 41.25, marking the lowest among them.

The kite diagram presented in

Figure 6 visually represents the sustainability index for ecovillage development in the Upper Citarum watershed. It is evident from the diagram that the cultural dimension boasts the highest sustainability index score, while conversely, the social dimension exhibits the lowest sustainability index score. This graph illustrates the sustainability status of ecovillage development in the Upper Citarum watershed, located within West Java Province, Indonesia, combining various dimensions of sustainability, specifically focusing on ecological, social, economic, and cultural aspects.

The findings emphasize that the cultural dimension attains the highest sustainability level. For instance, in the case of Cigentur Village, waste management practices were initiated even before the formal implementation of ecovillage development. These waste management customs, including sorting and repurposing, persist in the village. Notably, some villages experience a different trajectory, where activities associated with the development program tend to cease once the program concludes. This often occurs when leadership changes, resulting in a cycle of discontinuity.

Scholars, such as the authors of the reference from [

16], have asserted that the social aspect is a pivotal driving force within the ecovillage movement [

2]. Meanwhile, the authors of the reference from [

70,

82,

87,

95] have argued that what sets ecovillages apart from other communities is their adept combination of ecological and social interests. Ref. [

82] highlighted the significance of spiritual factors, and [

96] introduced political factors into the discourse. The inconsistency of the capitalist vision of sustainability is evident in their compartmentalized and unequal perspective in dealing with the various dimensions of sustainability. In the currently dominant model, sustainability is represented as having economic, social, and ecological dimensions which, in theory, are of equal importance and should be approached and worked on in an integrated manner. However, even in the respective discourse, the social dimension is largely ignored [

98,

99,

100,

101] and ecological concerns, albeit constantly “evoked”, rarely lead to any significant action. What happens in practice is that the economic dimension prevails to the detriment of all the others [

100,

102,

103]. It should also be noted that political and cultural aspects, which are theoretically “contained” in the social dimension, are usually obscured and cause debates about sustainability to get worse.

Hence, it is plausible to contend that the distinguishing feature of ecovillages lies in their comprehensive treatment of multiple dimensions of sustainability. This is exemplified by the widespread adoption of permaculture [

73], a system explicitly articulating ethical and design principles and adaptable to various facets of life.

5. Conclusions

The sustainability of ecovillage development in the Upper Citarum watershed hinges upon four interconnected dimensions of ecovillage sustainability: ecological, economic, social, and cultural. These dimensions operate in a mutually integrated manner. However, the current sustainability status of ecovillage development in the Upper Citarum watershed, situated within West Java Province, is categorized as “poorly sustainable”. Within the cultural dimension, the most influential attribute impacting the sustainability of ecovillages in the Upper Citarum watershed is the existing local culture within the community (RMS = 6.99). The established local culture, encompassing rules, norms, customs, and other cultural aspects, profoundly influences community activities.

In the social dimension, the attribute with the highest sensitivity is the type of creative economy business (RMS = 4.66). Developing creative economy businesses is expected to foster competitiveness and generate income for the community. The emphasis lies in fostering a creative economy rooted in local potential to facilitate access to standard materials. It is crucial to foster integration among ecovillage communities, ensuring that economic activities function cohesively and imbuing a sense of responsibility in all endeavors.

In the ecological dimension, agricultural waste disposal is the most sensitive attribute, with a value of 2.19. Waste disposal encompasses not only agricultural waste but also household waste, livestock waste, and other waste types, some of which are discarded without prior processing. While the cultural dimension achieves a status of “fairly sustainable”, the economic, social, and ecological dimensions are classified as “poorly sustainable”. This underscores the need for robust cooperation and active engagement among all stakeholders in developing these ecovillages.