Linking Irrational Beliefs with Well-Being at Work: The Role of Fulfilling Performance Expectations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Disentangling the Common and Distinctive Effects of Secondary Irrational Beliefs on Well-Being

1.2. The Fulfillment of Performance Expectations: A Missing Link between Secondary Irrational Beliefs and Well-Being at Work?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. Irrational Beliefs at Work

2.1.2. Performance Expectations Fulfillment

2.1.3. Well-Being at Work

2.2. Strategy of Analysis

- One-factor model, in which all 9 items measuring the three specific irrational beliefs are loaded on a general irrationality factor. The test of such a parsimonious model excludes the influences of method bias on observed item covariances [59].

- Three-correlated factors model, in which the items are loaded on the hypothesized three latent dimensions under the assumption that covariances among specific irrational beliefs may exist but are not explained by a common underlying irrationality factor.

- Higher-order model, in which the three irrational beliefs are loaded on a second-order irrationality factor that explains the covariations between the first-order factors.

3. Results

3.1. Validity and Reliability

3.1.1. The Factorial Structure of Irrational Beliefs

3.1.2. Validity and Invariance of the Measurement Model

3.1.3. Internal Consistencies

3.2. Hypotheses Testing

3.2.1. Zero-Order Correlations

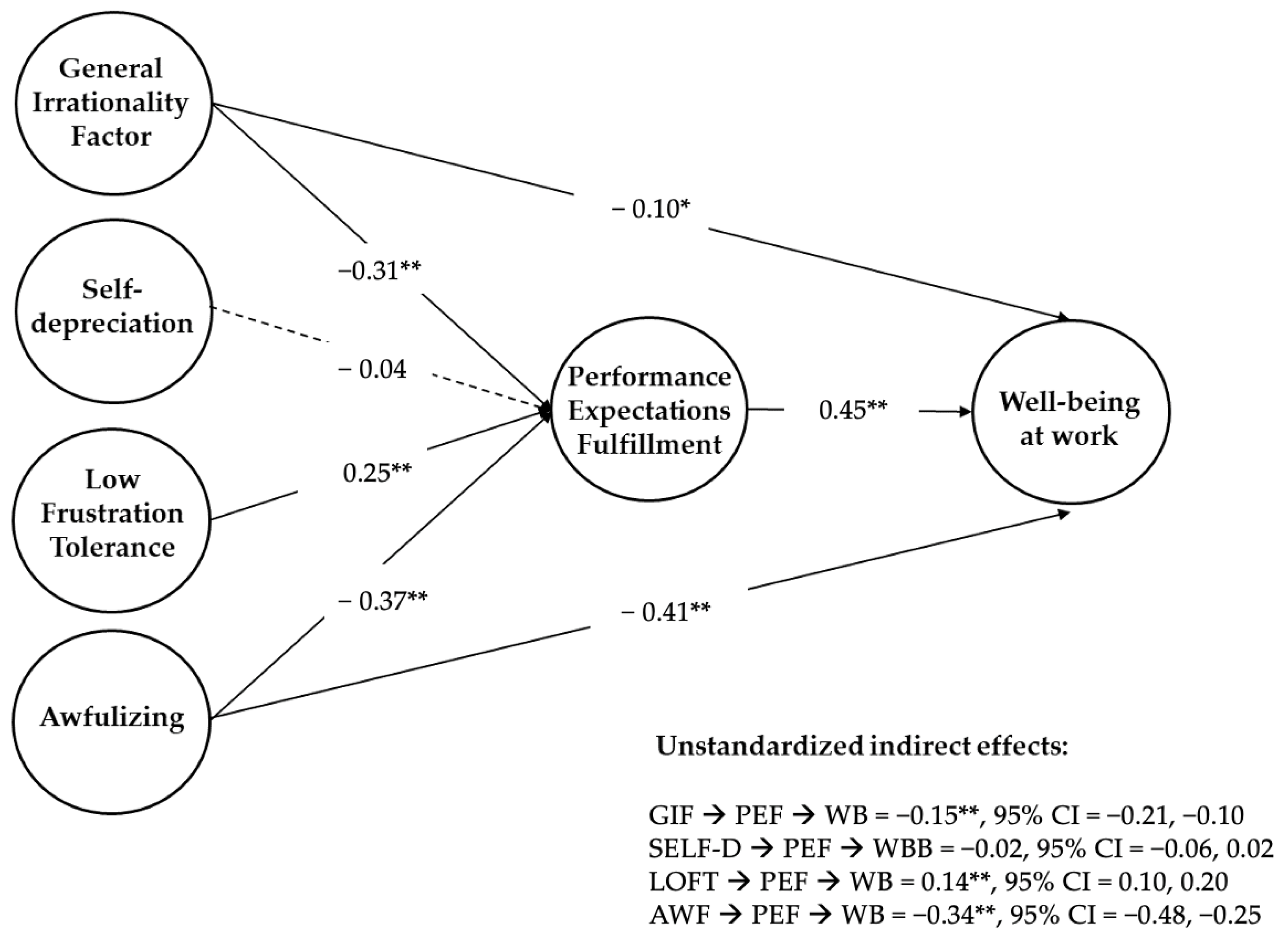

3.2.2. Structural Equation Modeling

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Studies

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Juchnowicz, M.; Kinowska, H. Employee Well-Being and Digital Work during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Information 2021, 12, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; van Woerkom, M. Strengths use in organizations: A positive approach of occupational health. Can. Psychol. 2018, 59, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, M.; Hansez, I.; Chmiel, N.; Demerouti, E. Performance expectations, personal resources, and job resources: How do they predict work engagement? Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 750–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeijen, M.E.L.; Brenninkmeijer, V.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Mastenbroek, N.J.J.M. Exploring the Role of Personal Demands in the Health-Impairment Process of the Job Demands-Resources Model: A Study among Master Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.A.; Michel, J.S.; Zhdanova, L.; Pui, S.Y.; Baltes, B.B. All Work and No Play? A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Correlates and Outcomes of Workaholism. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1836–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, A.C.G.; Wang, L.; Kiazad, K.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Ashkanasy, N.M. The relentless pursuit of perfectionism: A review of perfectionism in the workplace and an agenda for future research. J Organ Behav. 2020, 41, 144–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryden, W. “The cream cake made me eat it”: An introduction to the ABC theory of REBT. In Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy: Theoretical Developments; Dryden, W., Ed.; Brunner Routledge: Hove, UK, 2003; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A. Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy; Lyle Stuart: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A. Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy, rev. ed.; Birch Lane: Secaucus, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- David, D.; Cotet, C.; Matu, S.; Mogoase, C.; Stefan, S. 50 years of rational-emotive and cognitive-behavioral therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vîslă, A.; Flückiger, C.; Grosse Holtforth, M.; David, D. Irrational Beliefs and Psychological Distress: A Meta-Analysis. Psychother. Psychosom. 2016, 85, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.J.; Allen, M.S.; Slater, M.J.; Barker, J.B.; Woodcock, C.; Harwood, C.G.; McFayden, K. The Development and Initial Validation of the Irrational Performance Beliefs Inventory (iPBI). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 34, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Miller, A.; Youngs, H. The role of irrational beliefs and motivation regulation in worker mental health and work engagement: A latent profile analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wijhe, C.; Peeters, M.; Schaufeli, W. Irrational Beliefs at Work and Their Implications for Workaholism. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2013, 23, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, A.; Dal Corso, L.; Girardi, D.; De Carlo, A.; Barbieri, B.; Boatto, T.; Schaufeli, W.B. Why is perfectionism a risk factor for workaholism? The mediating role of irrational beliefs at work. TPM Test Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 24, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltean, H.R.; David, D.O. A meta-analysis of the relationship between rational beliefs and psychological distress. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.; DiGiuseppe, R. Are inappropriate or dysfunctional feelings in rational-emotive therapy qualitative or quantitative? Cogn. Ther. Res. 1993, 17, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. The Mental Health Continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing in Life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGiuseppe, R.; Leaf, R.; Gorman, B.; Robin, M.W. The Development of a Measure of Irrational/Rational Beliefs. J. Ration.–Emot. Cogn.–Behav. Ther. 2018, 36, 47–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGiuseppe, R.; Gorman, B.; Raptis, J.; Agiurgioaei-Boie, A.; Agiurgioaei, F.; Leaf, R.; Robin, M.W. The Development of a Short Form of an Irrational/Rational Beliefs Scale. J. Ration.–Emot. Cogn.–Behav. Ther. 2021, 39, 456–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, P.; Shevlin, M.; Adamson, G.; Boduszek, D. Modeling the Structure of the Attitudes and Belief Scale 2 using CFA and Bifactor Approaches: Toward the Development of an Abbreviated Version. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2014, 43, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Sun, T.; Cao, M.; Drasgow, F. Using bifactor models to examine the predictive validity of hierarchical constructs: Pros, cons, and solutions. Organ. Res. Methods 2021, 24, 530–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Joo, H.; Gottfredson, R.K. Why we hate performance management—And why we should love it. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Gottfredson, R.K.; Joo, H. Using performance management to win the talent war. Bus. Horiz. 2012, 55, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paré, G.; Tremblay, M. The Influence of High-Involvement Human Resources Practices, Procedural Justice, Organizational Commitment, and Citizenship Behaviors on Information Technology Professionals’ Turnover Intentions. Group Organ. Manag. 2007, 32, 326–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkis, M. Academic procrastination, academic life satisfaction, and academic achievement: The mediation role of rational beliefs about studying. J. Cogn. Behav. Psychot. 2013, 13, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano, G.; Gaudiino, M. Workaholism and work engagement: How are they similar? How are they different? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, D.; Swider, B.W.; Steed, L.B.; Breidenthal, A.P. Is perfect good? A meta-analysis of perfectionism in the workplace. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, M.; Venz, L.; Sonnentag, S. A dynamic view on work-related perfectionism: Antecedents at work and implications for employee well-being. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2022, 95, 846–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morkevičiūtė, M.; Endriulaitienė, A.; Poškus, M.S. Understanding the etiology of workaholism: The results of the systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2021, 36, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szentagotai, A.; Jones, J. The behavioral consequences of irrational beliefs. In Rational and Irrational Beliefs: Research, Theory, and Clinical Practice; David, D., Lynn, S., Ellis, A., Eds.; Oxford Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryden, W. Fundamentals of Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy; Whurr Publishers Ltd.: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Popov, S.; Sokić, J.; Antić, J. Occupational stressors and irrational beliefs as predictors of teachers’ mental health during the COVID-19 emergency state. Psihol. Istraživanja 2021, 24, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jooste, J.; Wolfson, S.; Kruger, A. Irrational Performance Beliefs and Mental Well-Being Upon Returning to Sport During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Test of Mediation by Intolerance of Uncertainty. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 2023, 94, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.; Davies, M.F.; Dryden, W. An experimental test of a core REBT hypothesis: Evidence that irrational beliefs lead to physiological as well as psychological arousal. J. Ration.–Emot. Cogn.–Behav. Ther. 2006, 24, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschmann, T.; Horn, R.A.; Blankenship, V.R.; Garcia, Y.E.; Bohan, K.B. The Relationship Between Automatic Thoughts and Irrational Beliefs Predicting Anxiety and Depression. J. Ration.–Emot. Cogn.–Behav. Ther. 2018, 36, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan HW, Q.; Sun CF, R. Scale development: Chinese Irrational Beliefs and Rational Attitude Scale. PsyCh J. 2019, 8, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGiuseppe, R.A.; DiGiuseppe, R.; Doyle, K.A.; Dryden, W.; Backx, W. A Practitioner’s Guide to Rational-Emotive Behavior Therapy, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tecuta, L.; Tomba, E.; Lupetti, A.; DiGiuseppe, R. Irrational beliefs, cognitive distortions, and depressive symptomatology in a college-age sample: A mediational analysis. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2019, 33, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popov, B.; Popov, S. Adverse Working Conditions, Job Insecurity and Occupational Stress: The Role of (Ir)rational Beliefs. J. Ration.–Emot. Cogn.–Behav. Ther. 2013, 31, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, D. Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT). In The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology; Cautin, R.L., Lilienfeld, S.O., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK; Malden, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.C.; Dahlen, E.R. Irrational Beliefs and the Experience and Expression of Anger. J. Ration.–Emot. Cogn.–Behav. Ther. 2004, 22, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, G.; Kufakunesu, M. The relationship between irrational beliefs, socio-affective variables and secondary school learners’ achievement in mathematics. Indep. J. Teach. Learn. 2021, 16, 118–132. [Google Scholar]

- Stanciu, M.M.; Dumitru, H.; Mocanu, D.; Mihoc, A.; Gradinaru, B.G.; Panescu, C. The connection between gender, academic performance, irrational beliefs, depression, and anxiety among teenagers and young adults. Rom. J. Cogn. Behav. Ther. Hypn. 2014, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Balkis, M.; Duru, E. Procrastination and Rational/Irrational Beliefs: A Moderated Mediation Model. J. Ration.–Emot. Cogn.–Behav. Ther. 2019, 37, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesagno, C.; Tibbert, S.J.; Buchanan, E.; Harvey, J.T.; Turner, M.J. Irrational beliefs and choking under pressure: A preliminary investigation. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2021, 33, 569–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G.L.; Hewitt, P.L.; Cheng, W.M.W. Perfectionism, Distress, and Irrational Beliefs in High School Students: Analyses with an Abbreviated Survey of Personal Beliefs for Adolescents. J. Ration.–Emot. Cogn.–Behav. Ther. 2008, 26, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, R.; Turner, M.J.; Kökény, T.; Tóth, L. “I must be perfect”: The role of irrational beliefs and perfectionism on the competitive anxiety of Hungarian athletes. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 994126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flett, G.L.; Hewitt, P.L. (Eds.) Perfectionism: Theory, Research, and Treatment; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Thoresen, C.J.; Bono, J.E.; Patton, G.K. The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 376–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkermans, J.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Brenninkmeijer, V.; Blonk, R.W.B. The role of career competencies in the Job Demands-Resources model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.S.; Diefendorff, J.M.; Erickson, R.J. The relations of daily task accomplishment satisfaction with changes in affect: A multilevel study in nurses. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, M.G.; Ilies, R. The role of self-efficacy, goal, and affect in dynamic motivational self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2009, 109, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.D.; Noble, C.S. A Within-Person Examination of Correlates of Performance and Emotions While Working. Hum. Perform. 2004, 17, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, G.; Borgogni, L.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Caprara, G.V.; Consiglio, C. From positive orientation to job performance: The role of work engagement and self-efficacy beliefs. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 767–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Credé, M.; Harms, P.D. 25 years of higher-order confirmatory factor analysis in the organizational sciences: A critical review and development of reporting recommendations. J. Organiz. Behav. 2015, 36, 845–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, A.; Reise, S.P.; Haviland, M.G. Evaluating bifactor models: Calculating and interpreting statistical indices. Psychol. Methods 2016, 21, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Dev. Rev. 2016, 41, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeish, D. Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychol. Methods 2018, 23, 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Fairchild, A.J.; Fritz, M.S. Mediation analysis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, M.E. Teacher Beliefs and Stress. J. Ration.–Emot. Cogn.–Behav. Ther. 2016, 34, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsiki, A.; Minnaert, A.; Katsikis, D. Relationships between self-downing beliefs and math performance in Greek adolescent students: A predictive study based on Rational-Emotive Behavior Education (REBE) as theoretical perspective. J. Fam. Med. Community Health 2017, 4, 1132. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T. Thinking and depression: I. Idiosyncratic content and cognitive distortions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1963, 9, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel-Kröhler, A.; Turner, M.J. Link between irrational beliefs and important markers of mental health in a German sample of athletes: Differences between gender, sport-type, and performance level. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 918329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, M.J.; Allen, M.S. Confirmatory factor analysis of the irrational Performance Beliefs Inventory (iPBI) in a sample of amateur and semi-professional athletes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 35, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, D.; Szentagotai, A.; Eva, K.; Macavei, B. A synopsis of rational-emotive behavior therapy (REBT); fundamental and applied research. J. Ration.–Emot. Cogn.–Behav. Ther. 2005, 23, 175–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.J.; Barker, J.B. Using rational emotive behavior therapy with athletes. Sport Psychol. 2014, 28, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.R.; Szamoskozi, S. A meta-analytical study on the effects of cognitive behavioral techniques for reducing distress in organizations. J. Evid.-Based Psychother. 2011, 11, 221. [Google Scholar]

| Models | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA [CI 95%] | SRMR | Δχ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-factor model one factor for all items. | 1348.93 * | 27 | 0.66 | 0.54 | 0.17 [0.16, 0.18] | 0.10 | 1212.48 * (df = 9) |

| 3-factors model three factors representing awfulizing, low frustration tolerance and self-depreciation. | 168.48 * | 24 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.06 [0.05, 0.07] | 0.04 | 32.03 * (df = 6) |

| Higher-order model the three factors loaded on a second-order irrationality factor. | 204.22 * | 25 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.07 [0.06, 0.07] | 0.05 | 67.77 * (df = 7) |

| Bifactor model the three orthogonal factors and all items loaded on a general irrationality factor. | 136.45 * | 18 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.06 [0.05, 0.07] | 0.03 | - |

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA [90%CI] | SRMR | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | ΔSRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural invariance | 480.51 * | 142 | 0.964 | 0.947 | 0.052 [0.048 0.058] | 0.044 | - | - | - |

| Metric invariance | 512.87 * | 160 | 0.962 | 0.951 | 0.051 [0.046 0.056] | 0.048 | 0.002 | −0.001 | 0.004 |

| Scalar invariance | 576.41 * | 175 | 0.957 | 0.949 | 0.052 [0.047 0.057] | 0.052 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.004 |

| Residual invariance | 640.46 * | 190 | 0.952 | 0.947 | 0.053 [0.49 0.058] | 0.056 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA [90%CI] | SRMR | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | ΔSRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural invariance | 481.02 * | 142 | 0.964 | 0.947 | 0.052 [0.048 0.058] | 0.045 | - | - | - |

| Metric invariance | 521.36 * | 160 | 0.961 | 0.949 | 0.051 [0.047 0.056] | 0.050 | 0.003 | −0.002 | 0.005 |

| Scalar invariance | 619.65 * | 175 | 0.953 | 0.943 | 0.055 [0.050 0.059] | 0.060 | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.010 |

| Residual invariance | 685.08 * | 190 | 0.947 | 0.942 | 0.055 [0.051 0.060] | 0.070 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.010 |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | General Irrationality Factor | 3.15 | 0.75 | - | |||||

| 2. | Self-depreciation | 2.85 | 0.97 | 0.81 ** | - | ||||

| 3. | Low Frustration Tolerance | 4.45 | 0.97 | 0.72 ** | 0.33 ** | - | |||

| 4. | Awfulizing | 2.34 | 0.93 | 0.77 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.26 ** | - | ||

| 5. | Performance Expectations Fullfilment | 5.38 | 0.97 | −0.18 ** | −0.20 ** | 0.10 * | −0.31 ** | - | |

| 6. | Well-being at Work | 4.74 | 1.24 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.22 ** | 0.58 ** | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santarpia, F.P.; Bodoasca, E.; Cantonetti, G.; Ferri, D.; Borgogni, L. Linking Irrational Beliefs with Well-Being at Work: The Role of Fulfilling Performance Expectations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16463. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316463

Santarpia FP, Bodoasca E, Cantonetti G, Ferri D, Borgogni L. Linking Irrational Beliefs with Well-Being at Work: The Role of Fulfilling Performance Expectations. Sustainability. 2023; 15(23):16463. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316463

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantarpia, Ferdinando Paolo, Emma Bodoasca, Giulia Cantonetti, Donato Ferri, and Laura Borgogni. 2023. "Linking Irrational Beliefs with Well-Being at Work: The Role of Fulfilling Performance Expectations" Sustainability 15, no. 23: 16463. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316463