1. Introduction

Globally, there is increasing pressure on young consumers to be mindful of their purchasing behaviours to encourage sustainable consumption [

1], with young female adults representing a large proportion of fashion consumption [

2]. Clothing production and consumption systems urgently need to be changed to reduce the world’s waste and carbon emissions [

3,

4]. To give a sense of the scale of the problem, each year Australians purchase approximately 15 kg (56 pieces) of new clothing per person, which, in a country with a population of 26 million, nationally equates to 383,000 tonnes, with a similar amount discarded each year [

5]. Clothing and textiles have been identified by governments internationally as a waste priority area, for example, in Europe via the Green Deal and Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP), in the UK via Textiles 2030, or in Australia via the recent launch of the National Product Clothing Stewardship scheme, Seamless [

3,

6,

7,

8] One strategy for sustainable consumption is to increase the purchasing of secondhand clothing, rather than the purchasing of new clothing, with many services and systems rapidly emerging to support and commercialise this consumption practice [

3]. Given this recent policy focus and commitment to reducing textile waste, it is timely to identify the current beliefs contributing to young women’s secondhand clothing purchasing decisions. This focus is consistent with the recirculation pathway of waste reduction strategies and this research responds directly to the recognised need for “consumer surveys to understand acquisition, use and disposal practices and opportunities for behaviour change” [

3] (p. 6), with the expectation that such research can guide shared responsibility to reduce the environmental and social impacts of the entire clothing life cycle.

To encourage the purchasing of secondhand clothing, it is important to understand the factors that influence this purchasing behaviour. Well-validated decision-making models might be usefully employed to assist in understanding the beliefs underlying young women’s purchasing decisions. Two commonly used models to understand people’s decisions are the Theory of Planned Behaviour [

9] and the Prototype Willingness Model [

10].

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) [

9] states that attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control are the three main contributors to people’s intentions and the best predictor of behaviour [

9,

11]. Attitudes towards a behaviour refer to a person’s positive or negative evaluation of that specific behaviour, and attitude is an established influence on people’s intention to perform a behaviour [

9]. Attitudes are developed from an individual’s beliefs, which are formed when associating an object with certain attributes that are favourable (advantages) and unfavourable (disadvantages) [

9]. Therefore, an individual is observed to link a behaviour to a particular outcome that will be valued positively or negatively by the individual [

9]. In the context of this research, the perceived advantages and disadvantages of purchasing secondhand clothing are expected to reflect young women’s behavioural beliefs related to purchasing secondhand clothing.

Subjective norm is a second major influence on people’s intentions to perform a behaviour and describes how an individual’s intention can be motivated by societal norms and influences such as friends and family and the probability that significant others in people’s lives serve to encourage the performance of the behaviour [

12,

13]. Normative beliefs, which underlie subjective norms, reflect the perceived pressure to engage in a certain behaviour applied by significant referent individuals or groups such as the individual’s spouse, friends, and family [

14]. These influences can extend to teachers and co-workers [

14]. Accordingly, identifying the key referents associated with the approval and disapproval of secondhand clothes purchases establishes the perceived normative beliefs among this cohort.

Perceived behavioural control refers to an individual’s perception of the difficulty of performing an action. This is related to the barriers and facilitators associated with a behaviour, which can vary across different situations [

9,

14]. Internal forces, such as an individual’s skill set, and external forces, such as opportunity, impact the perceived ease of completing a task [

12]). Ajzen suggests that this notion of control is self-evident as the resources and opportunities available to complete an action will dictate whether an action is performed. Ajzen and Madden’s [

12] research suggests that perceived behavioural control contributes significantly more to intention in comparison to attitudes and subjective norms. Perceived behavioural control is specifically important to the TPB as it is also believed to directly influence behaviour, unlike subjective norms and attitudes, which are thought to only influence people’s intentions. This element of the TPB, control beliefs, is represented in this research as reflecting current barriers and facilitators to secondhand clothing purchasing behaviours among young women.

Meta-analytic evidence has pointed to the utility of the TPB across a variety of behavioural domains [

15], with it being particularly prominent in the study of sustainable fashion and specifically secondhand clothing consumption [

16,

17]. For example, a US study using the TPB [

18] examined the factors that influence shoppers to purchase secondhand clothes in non-profit stores. The results indicated that consumers’ environmental beliefs and beliefs regarding non-profit stores influenced positive attitudes, which had the largest significant influence on purchase intention. In addition, this study revealed that subjective norms had an indirect effect on purchase intention by impacting attitudes. Additionally, a Brazilian study by Lira and Costa [

19] examined consumers’ ethical considerations and conscious consumption intentions on the purchase of slow fashion using the TPB. The results indicated that perceived behavioural control was positively associated with purchasing slow fashion, suggesting that participants believed they had control over their sustainable actions. Drawing from a TPB approach, identifying the beliefs underlying the direct constructs of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control may assist in developing targeted strategies and messaging addressing the cognitions contributing to secondhand clothing purchasing (and non-purchasing) behaviours among young women. While the TPB is useful in understanding the prediction of people’s intentions, other models may be more useful for reflecting people’s more spontaneous purchasing decisions.

The Prototype Willingness Model (PWM) incorporates elements of the TPB and utilises a modified dual-process model originally intended to understand adolescents’ health risk behaviour [

10,

20] and is heavily focussed on volitional yet non-intentional risk behaviours [

10]. The PWM extends upon the TPB, not only reflecting the main influences of people’s intentions but further including the determinants of individuals’ willingness to perform a behaviour even if they were not explicitly intending to perform it (e.g., not intending to buy secondhand clothing but passing by a charity shop with an attractive display of clothes and spontaneously deciding to wander in and purchase). This model may be particularly relevant in the present context as clothing purchasing as a behaviour is often spontaneous, particularly for women [

21,

22]. However, as far as we can discern, as of yet, these two theories have not been used in conjunction regarding secondhand clothing [

16].

According to the model, intention is influenced by attitudes and subjective norms. Willingness is influenced by three key factors: attitude, subjective norms, and prototypes [

23]. Gibbons et al. [

23] state that a positive attitude towards a particular behaviour is associated with greater behavioural willingness to engage in that behaviour, and subjective norms are characterised by the perception that those important to us would also engage in the behaviour and, thus, would not disapprove of one’s participation [

23]. Prototype comprises favourability, i.e., whether an individual views a prototypical image or description of a typical performer as favourable or unfavourable, and similarity, i.e., an individual’s view of their similarity to the image or description [

23]. For instance, prototypes of environmentalists have been found to predict self-reported engagement in environmentally friendly behaviours [

24]. A meta-analysis by Todd et al. [

25] further substantiated the PWM through their review of 81 studies, finding that the PWM explained 20.5% of the variance in behaviour, and willingness explained a 4.9% variance in behaviour over and above intention. Eliciting descriptors of the typical images of those who purchase secondhand clothing and those who do not, as carried out in this research, can establish the relevant prototypes among this cohort. In the current context, it would be expected that the more favourable a young woman’s image is of the typical young woman who purchases secondhand clothing and the more similar they feel to the image, the more willing she will be to buy secondhand clothing.

Alongside the TPB and PWM, other theoretical perspectives have been used to examine the topic of secondhand clothing purchases. These include the Norm Activation Model [

26], the role of self-concept [

17], and green identity [

27]. More broadly, other research has identified beliefs contributing to young women’s secondhand clothing decisions (see [

26,

28,

29]). Most pertinent is recent research providing various categories or frameworks for the motivations for purchasing secondhand. Popular amongst these frameworks is the work of Guiot and Roux who posit critical motivations (morally or ethically driven consumption practices in response to social or environmental concerns), economic motivations regarding price and bargain hunting, and recreational or hedonic motivations that include aspects like sociability, treasure hunting, and nostalgic pleasure [

30]. To these three motivations, Ferrararo et al. add “fashionability” in response to the growing popularity of secondhand and vintage fashions [

31]. Similarly, Diddi et al. offer perceived value, sustainability commitment, and uniqueness as motivators for purchasing secondhand and perceived lack of variety/style, scepticism about clothing hygiene and previous owners, and emotions attached to consumption as primary reasons not to purchase secondhand [

32]. While these categories help analyse the responses, as Machado et al. note, the motivating factors for secondhand purchases frequently overlap [

33]. Teasing out the nuances in motivating and inhibiting factors informing young women’s fashion purchasing behaviour is the purpose of this research.

2. Materials and Methods

Our objective with this research was to explore the underlying beliefs inherent in two major decision-making models, the TPB and PWM, to identify the key drivers that might be informing young women’s secondhand purchasing decisions. This research aims to extend past research in the more specific context of young Australian women and their attitudes towards purchasing secondhand clothing by exploring theory-based beliefs determining their purchasing decisions. Importantly, elicitation of underlying beliefs according to the TPB allows for the identification of target beliefs for a given population as part of formative research for subsequent quantitative and intervention work focusing on people’s salient cognitions. This research targeted young women aged 18 to 25 years who currently live in Australia. This focus was determined by two factors. The first is the outsize proportion of fashion consumption of this gender group and age bracket [

2,

34]. The second, and related factor, is the fact that women’s clothes predominate in the Australian secondhand market [

35], which is currently handling and sorting almost 800 million items of clothing annually and exporting an estimated 62% of these overseas [

5]. Combined, this suggests that shifting clothing purchasing patterns of young women is more likely to make a discernible contribution to sustainable consumption and be a welcome intervention in the Australian market to keep products onshore.

This exploration was based on the TPB, using a qualitative survey to identify the beliefs underlying attitudes (advantages and disadvantages), subjective norms (specific referents who approve and disapprove), and perceived behavioural control (barriers and facilitators) for secondhand clothing purchasing decisions. From a PWM perspective, ideas about the image of the typical young woman who purchases (and does not purchase) secondhand clothing can assist in informing the prototype component of the model, which is understood to predict people’s willingness to engage in the behaviour. By drawing from both the TPB and PWM, an understanding of underlying beliefs can be established for young women’s intentional secondhand clothing purchasing (belief base of the TPB with a focus on understanding buying intentions) and spontaneous buying (the prototype images component of the PWM influencing people’s willingness to buy). Open-ended questions were asked about each of these underlying beliefs and prototypical images concerning secondhand clothes shopping, with a final question asking for any further comments about the topic.

In December 2022 and January 2023, participants completed an anonymous online qualitative survey with a series of demographic as well as open-ended questions [

36]. An online survey was selected as a data collection method that matched our target population, enabled participant diversity, and provided rich topic-focused data [

37]. In particular, as the target participants are in a generation actively engaged in social media platforms and comfortable with communicating online, they were expected to be comfortable expressing themselves in an online survey [

37]. Seventy-six participants consented to participate and commenced the survey. Of these participants, 28 either did not answer any questions or only answered the initial demographic questions and were, therefore, not included in the analysis. This exclusion left a total of 48 valid responses, which is an appropriate sample size for the research project focus and the analysis approach [

38]. The recruitment of participants continued until the saturation of data, which was recognised to be when no new themes were being generated [

39].

To obtain a wide range of perspectives on the topic, participants were recruited from a variety of sources. The survey was promoted via online advertising on social media, the researchers’ personal social media, university newsletters, physical posters, and snowballing, wherein existing research participants are used to find and recruit additional participants with the same characteristics, in this case, young Australian women [

40].

Due to our concerns that using researchers’ networks to promote the study would potentially skew the survey demographics towards more university-educated and urban-based women, several different strategies were implemented to reach as many participants as possible, and thus ensure diversity in demographics, clothing purchasing practices, and backgrounds. These included designing recruitment materials that did not specify that the study focused on secondhand clothing to ensure people who purchased and did not purchase secondhand clothing participated; distributing the survey via multiple different social media platforms from a variety of accounts (including personal and institutional) to reach a variety of users; and offline recruitment and survey promotion via physical posters with a QR code included that connected to the survey distributed to nine charity clothes stores across Queensland, Australia. The last strategy was particularly important for reaching different areas of residency and a non-student population. A comparison with data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics suggests that these strategies were mostly successful, with our sample being representational of the population of young women in Australia in terms of area of residency and close to representational in terms of income, but less likely to be working full time and more likely to be working part-time than the national profile of young women in Australia [

41].

The analysis of the survey responses was conducted using NVivo (version 14) [

42], a qualitative analysis software. The analysis was completed through the process of coding and Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis [

43]. Firstly, the researchers familiarised themselves with the data by reading through participant responses. Codes were then generated by two of the authors independently and compared to limit bias in the interpretation of results, with coding consensus reached after thorough discussion. Themes were developed by grouping codes of similar meaning together and were identified collaboratively by the authors and reviewed with two of the other authors to ensure accuracy and clarity of data interpretation. After themes were agreed upon, they were defined and named, generating the following findings.

3. Findings and Discussion

The results of our study draw together findings about the sociodemographic characteristics of participants, factors that influence intentional and spontaneous buying of secondhand clothing purchases, and additional areas of concern that did not fit neatly into the frameworks of existing research. Reflecting our overarching concern that clarifying the intersections and contextual context of participants’ responses is foundational to identifying nuances in the underlying beliefs driving young women’s fashion choices, here the findings and discussion are combined.

Firstly, it is useful to understand the sociodemographic characteristics of the survey participants. For the 48 young women whose responses were analysed, the average age of the participants was 20.85 years (SD = 2.14), and they were mostly from metropolitan areas, working casually or part-time, and earning under AUD 50,000 gross per annum (see

Table 1). Most participants browsed for clothing both online and in physical stores (

n = 36), with around a fifth of participants browsing in physical stores only (

n = 10). Only two of the participants browsed for clothes online exclusively. For purchasing clothing, most participants purchased clothing using a combination of online and physical store options (

n = 27), with 19 participants purchasing clothing in physical stores only and 2 participants purchasing exclusively online. Of the 41 women who purchased secondhand clothing at least occasionally, the majority purchased them at thrift/charity shops, with markets, vintage/consignment stores, or online at Facebook Marketplace making up the bulk of the other purchasing methods. In the last 12 months, participants spent an average of AUD 959 on buying new clothes and AUD 240 on buying secondhand clothes. On average, approximately 37% (range 0–90%) of all participants’ wardrobes were secondhand clothing. As several participants themselves highlighted, purchasing is not the only way to obtain secondhand clothing; some were obtained through such mechanisms as hand-me-downs, gifts, and clothing swaps. As such, even those who never purchased secondhand clothes noted they had secondhand items in their wardrobes.

3.1. Factors That Influence Intentional Secondhand Clothing Purchases

Responses to questions about the behavioural, normative, and control beliefs for secondhand clothes suggest that several consistent factors influence the intentional purchase of secondhand clothing. Correlating with, and following the research of, Guiot and Roux, Diddi et al., and Ferraro et al. [

30,

31,

32,

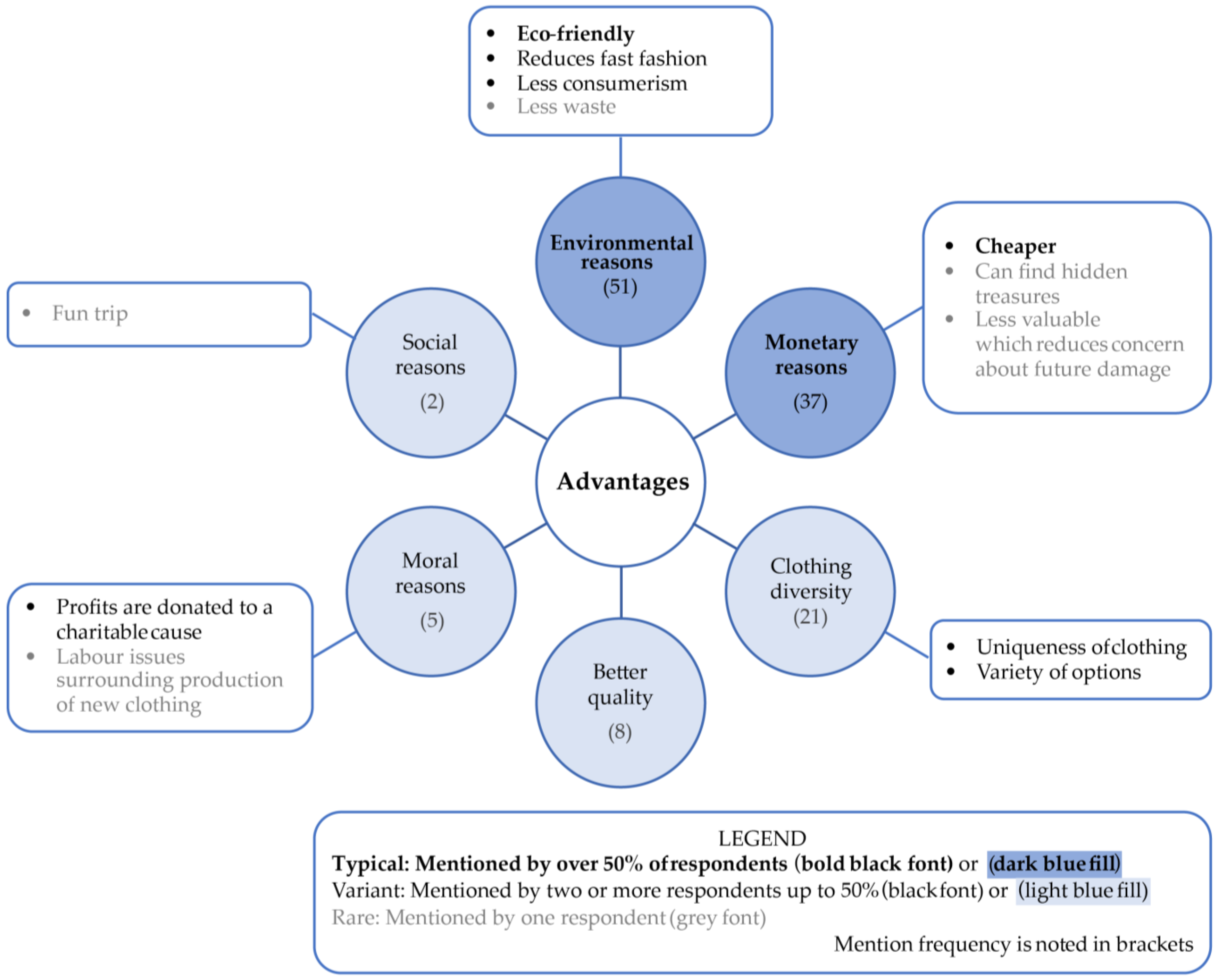

37], the findings regarding the advantages, facilitators, disadvantages, and barriers to purchasing secondhand clothing can be divided into ethical positioning, prices and value, perceptions of the clothing stock, and the shopping experience. As shown in

Figure 1, and discussed in further detail below, environmental impact and monetary reasons dominate advantages. Price, diversity, and quality of clothing stock and the retail experience are facilitators that encourage or could encourage the purchase of secondhand clothing as seen in

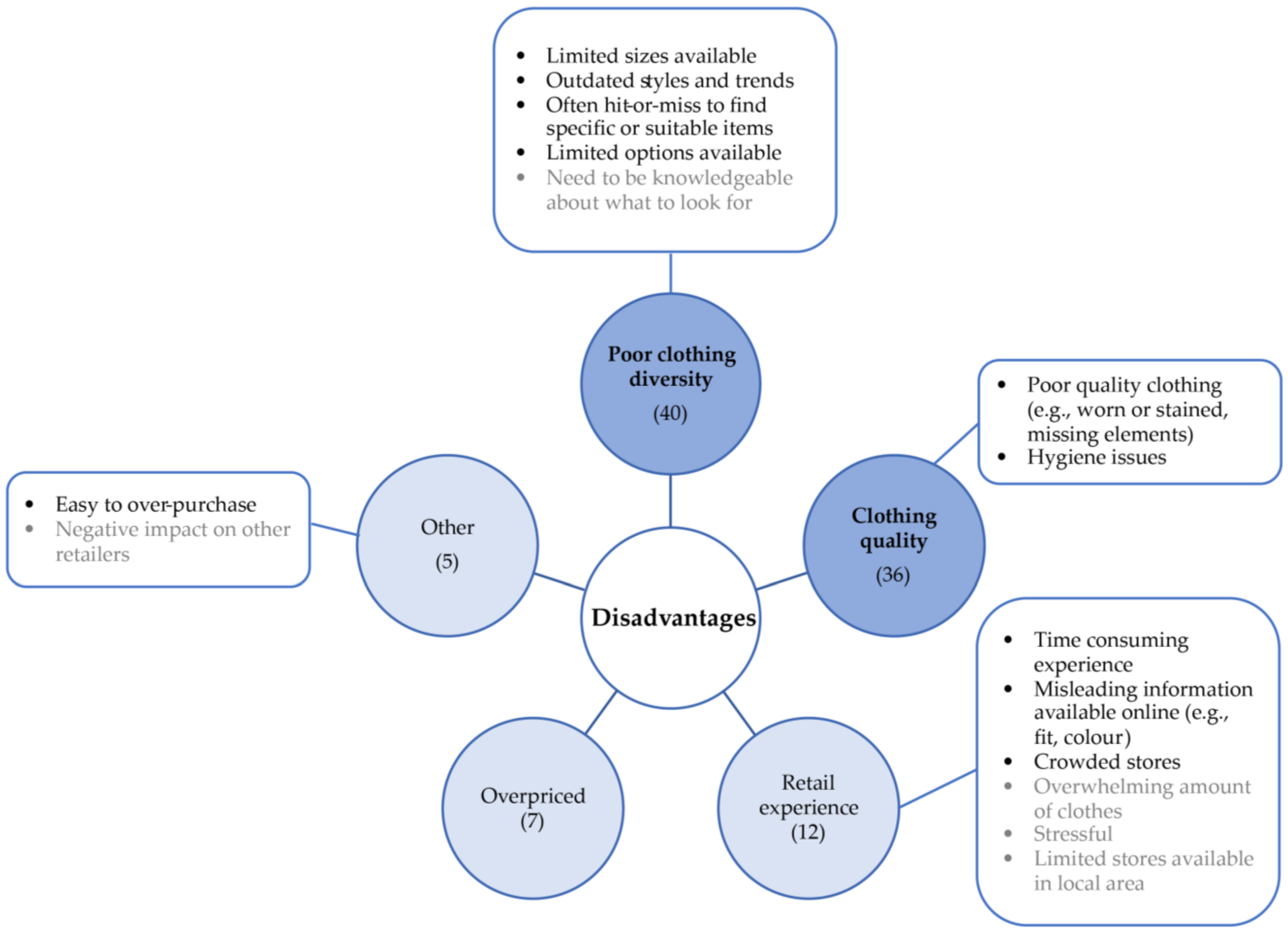

Figure 2. The disadvantages and barriers, visible in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, respectively, are led by concerns about clothing diversity and quality. The significant overlap in responses suggests that there is a close alignment in positive and negative attitudes and control perceptions regarding secondhand clothing. As such, these factors are addressed together, bolstered by responses to questions about subjective norms. This approach makes clear connections between findings and enables a more nuanced analysis.

3.1.1. The Ethics of Secondhand

The results suggest that young women consider secondhand clothing as a more environmentally conscious and sustainable way to consume fashion, and this is a driving motivation. This attitude holds both for those who are purchasers of secondhand clothing and those who are not, with six of the seven respondents who do not purchase secondhand clothing mentioning environmental sustainability factors as an advantage. This primacy is consistent with similar research in 2019 in the US [

32], but contrasts with 2016 data coming from Brazil, which drew on older demographic [

33]. We highlight this as it not only evidences global variations in motivating concerns but also shows that environmental concerns are rapidly becoming central, especially for young consumers. Importantly for participants, as “the clothing industry is also a large contributor to global emissions and environmental pollution”, “secondhand clothing bypasses these impacts”. Effectively, secondhand clothing is seen as a way to circumvent the fashion system, in particular, the perils of “fast fashion”.

Fast fashion, associated with overproduction and overconsumption of cheap, novelty-driven, and quickly disposed of garments [

44,

45], was frequently and always negatively mentioned by participants. Deploying secondhand purchasing as a strategy to circumvent the ecological impact of clothing consumption is consistent with previous research [

33,

46]. Consumers consider that purchasing secondhand not only enables them to avoid or not support “fast fashion” in particular but also the social justice issues it is commonly associated with, such as exploitative labour practices [

17]. This concern is visible in survey responses that raised “reducing contributions toward unfair labour and sweatshops” and the “human cost of mass production of clothes” as reasons to buy secondhand. Notably, secondhand was also seen as a way to access a company’s clothing without supporting the company itself, i.e., as a way to buy “brands that make cool stuff who have a shit CEO”. Here, participants consider financially supporting a company or brand via direct purchases more of an ethical concern than supporting a brand through association via wearing its clothing.

Connecting to this ecological value of purchasing secondhand is the moral value participants attribute to this consumption pattern. It might be via where the profits from purchases go to, in the case of those who shop at charity stores, or the positive feeling of “doing good”. Respondents specifically connected this form of purchase with mental benefits for them as individuals as well as the wider benefits for the community, whether social or ecological. Evidence suggests peer influence plays a significant role in sustainable consumer behaviour [

32]. This point correlates with our findings that suggest these values might be generational, with peers and friends more likely to approve of purchasing secondhand clothing and older relatives such as grandparents mentioned most often as likely to disapprove (see

Table 2), specifically because participants perceive this older generation “don’t … understand the sustainability aspect of it”. This presumption is borne out by the work of others, with young people’s recognition of climate change issues shown to be greater than those who are older [

47].

In contrast to this positioning is the perceived ethical risks that come from shopping secondhand, particularly around overconsumption. Respondents raised the point that the low prices and abundant stock of secondhand can lead to impulse purchases and “buying more than what you need”. One participant even suggested that her parent disapproved of purchasing secondhand “because they see the trap of falling into overconsumption with it”. Effectively, participants suggest that purchasing secondhand does not avoid the ethical concerns of overconsumption, echoing points raised elsewhere [

7].

Regarding the business models, one respondent suggested that “unfair” profits or not knowing where profits were going was a concern that would prevent their purchase, while another suggested that “less business for normal retail” was a disadvantage. Aligning with these perspectives, one participant expanded as follows:

“Secondhand clothing stores often seem poorly managed and have very little knowledge of the items they are selling. This leads to markups that are greater than the original sale price … The biggest appeal should be its affordability but when it cannot even offer that, most people who would otherwise shop secondhand have no choice but to resort to cheaper options”.

While nominally addressing price, such comments reflect the expected social responsibilities of secondhand (often charity) stores to provide the cheapest option, and so facilitate secondhand and thus sustainable purchases across all income demographics. These responses suggest that, for some, the business models for secondhand raise their own ethical concerns. This perspective complicates the presumed moral value associated with secondhand purchases and the findings of Seo et al. [

17] in which the non-profit status of retailers favourably influences attitudes toward secondhand clothing.

3.1.2. Value and Pricing

Price was considered both a major advantage and encouragement to purchasing secondhand and also, albeit to a lesser extent, a disadvantage and barrier to purchasing. Cost is a key reason why people purchase secondhand clothing [

32,

46,

48], and, locally, a turn to secondhand shopping has been connected to the rising cost of living in Australia [

49]. Terms like “cheaper”, “save money”, and “less expensive” were often used to describe the advantages and encouragements of purchasing secondhand clothing. Participants also explicitly used the cheaper cost of secondhand clothing as a way to experiment with their style, noting they “can find a[nd] test a variety of styles for relatively cheap” using secondhand clothing.

However, many participants reported they thought that prices for secondhand clothing were increasing, which is a point borne out by research [

50]. It was considered particularly relevant for purchases made online or of vintage clothing which “can be overpriced due to its popularity at the moment”. These responses reflect that, as the trend for vintage clothing has become more mainstream, sellers are using consumer demand to increase prices [

51,

52]. This shift to the mainstream is connected to changing norms, via comments like “everyone” approving of secondhand as it is “the tReNd (sic) right now and not seen as cringe or broke”. Also critiqued as a barrier were the high prices of “boutique’ op-shops” (a colloquialism used in Australia or New Zealand for a shop selling secondhand goods for charitable funds) or “secondhand stores that try to act like an actual store”. Implicit in these kinds of comments is an expectation that secondhand shopping involves a certain kind of store experience.

There are also concerns specific to online retailers. For many, “price gouging” or “overpricing on resell apps” discourages purchases and, as well as being described as more expensive, online purchases come with additional specific costs of “expensive postage”. Overpricing is also contributing to a distrust of the market, evident in comments like “sometimes depop girlies will sell u (sic) some [online fast fashion retailer] SHEIN crap and mark it as vintage and sell it for $40 so you got to be careful of scammers”.

While prices might be rising for secondhand clothing, a contributing factor to this barrier is the lowering cost of new clothing [

53,

54]. Survey responses make this explicit, with participants noting the “unrealistic markups by secondhand clothing stores- it is becoming more affordable to buy brand new clothes” or how they “can get clothing just as cheap new and not smelly at [discount retailer] Kmart”. Young consumers expect the cost of secondhand clothing to be lower than new clothing, and price-driven consumers will switch to new clothing sources if they are not.

Another aspect of the factor is the value placed on these clothes. One participant mentioned valuing secondhand as she did not “need to get too worried if it gets ruined or dirty”, but predominantly participants suggested, via phrases like “good deals”, “hidden treasures”, or stating that they “can find high-end brands for cheap prices”, that saving money was a key consideration. This finding highlights the aspect of bargain hunting involved with secondhand shopping, which is an appealing activity for many shoppers [

55,

56,

57]. However, as O’Reilly et al. [

58] establish, low price alone is not sufficient to prompt a purchase, and the merchandise quality and diversity influence resale to a greater extent. This point moves us on to the next major factor, that of the clothing stock.

3.1.3. Clothing Stock

The perceptions of the types of clothing available as secondhand were a crucial factor in its consumption. The comments and responses regarding the clothes are divided into two areas of concern, these being the diversity of the clothes and the quality of the clothes.

The diversity of the clothes was considered both an advantage and disadvantage and a barrier and facilitator to purchasing. This factor connects to the motivating category of fashionability identified by Ferrararo et al., which they define as “motivations are related to the need for authenticity and originality, but specifically, concern attempts to follow a specific fashion trend, create a personal and unique fashion style, or avoid mainstream fashion” [

31] (p. 264). Similar to Diddi et al. [

32], as an advantage or facilitator, secondhand clothing was most frequently reported as being “unique” or valued for not being able to be found elsewhere. Comparable phrases related to ‘clothing diversity’ included “trendy”, “lots of options”, the “chance to find vintage/discontinued items”, and “better selection”, which were the second most mentioned phrase concerning encouragers. This theme relates to the previously mentioned point of treasure hunting; if secondhand stores have a wide variety of clothes or unique clothing, shoppers are more likely to visit the stores in the hope of finding something not available elsewhere.

However, diversity was also positioned as a detractor, dominating as a disadvantage (

Figure 3) and the second most mentioned barrier (

Figure 4). Common themes were the (lacking) fashionability of the garments themselves with ‘old styles or trends’ dominating by the nature of secondhand. While some respondents appreciated being able to shop outside of trends, with comments like “sometimes the current fast fashion trends are just not the vibe so I look to secondhand shopping to … find something that fits my personality”, more frequently the “outdated” clothes were considered a detractor unless it was a universally approved of “vintage” item. Providing a nuance to this discussion is the opinion that shoppers “need knowledge of specific styles or brands to get what you’re looking for”. The knowledge requirement echoes concerns raised above about scammers mislabelling items as vintage for increased profits.

Another consideration in this vein was ‘sizing issues’, i.e., the fact that each item is generally a one-off and so frequently shoppers would encounter the disappointment of “cool clothes that are not in your size”. More broadly, there was a perception that secondhand clothes were “less accessible for bigger people” due to a “lack of size options”. Here, a known limitation of the fashion industry, the “difficulty in finding well-fitting fashionable clothing for larger people” [

59] unsurprisingly carries through to the secondhand market.

The final issue with the ‘limited options’ or diversity of clothing stock is its “hit and miss” nature, in which consumers are “not able to find the particular item I need or want”. This limitation means those intentionally shopping for a certain product or style are disadvantaged by the restricted selection of clothing items or have to spend more time and effort than they would like compared to shopping with retailers for new products in finding flattering or appropriately sized garments or adequate variety and fashionability.

The second area of concern was the mixed perceptions about the quality of secondhand clothing. Some participants associate secondhand with higher quality products, stating that “older clothes are made better” or “built to last”. Here, participants associate older garments with durability, presumably via sturdy manufacturing techniques or materials, reflecting the nostalgic dimension of secondhand shopping [

33]. However, over half of the participants’ responses raised poor quality clothes as a barrier or disadvantage of secondhand (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), suggesting the more common perception of secondhand clothing as it being obviously worn, damaged, dirty, or faded. Additionally, some buyers are deterred by the “amount of fast fashion starting to fill up these areas” or “increasing fast fashion/poor quality brands” in secondhand markets, reflecting a perception that the clothing stock is decreasing in quality with this influx.

As well as concerns about the wear of the garments, respondents also had concerns about who was wearing them or “not knowing who had it before and their hygiene levels”. Issues of ‘hygiene’ occurred repeatedly when describing secondhand clothes shopping, connected to stains, “foul odours”, and unknown prior ownership. Hygienic concerns have been demonstrated to act as a substantial barrier to the purchasing of secondhand clothing [

60,

61], and, as the impacts of COVID-19 have increased awareness of hygiene concerns, the pandemic may contribute to increasing hesitation in purchasing secondhand clothing items [

62].

3.1.4. The Shopping Experience

Participants emphasised how important the overall ‘shopping experience’ is in encouraging them to purchase secondhand clothing. The convenience of shopping, store location, store organisation (such as clothes grouped in sizes or colours and stores not being over-cluttered, disorganised, or overfull, making them overwhelming to shop in), accessibility, smell, and air-conditioning were all elements that would enhance the overall retail experience, with phrases on this topic being mentioned often. When particularly referring to accessibility in response to barriers, it should be noted that participants had simply stated the word without further explanation of its meaning. The researchers took this reference to either mean shoppers’ ease of access to the clothing (e.g., not being cluttered on racks) or to the shop itself (e.g., wheelchair access or convenient location or opening hours) (

Figure 4).

In some respects, the growth and popularity of online platforms such as Depop and Facebook Marketplace bypasses many of these accessibility issues. They have also increased the volume and availability of secondhand purchasing far beyond older place-specific models of secondhand markets, vintage stores, and charity shops [

31], which addresses some of the concerns about stock availability regarding diversity of sizes and ease of finding via filtering and search terms. However, these platforms, as well as raising pricing and trust concerns as noted above, come with their own challenges such as “clothes not what they looked like on model”, “photos/lighting can be misleading”, or “if u (sic) buy it online it can fit funny and have weird texture”. While the difficulty of assessing fit, fabric, and style is not limited to secondhand clothes when shopping online, “because it’s only the one piece and if it doesn’t fit that’s it”, the risks are perceived as higher than for other retailers that can offer returns and size exchanges.

The other crucial part of the shopping experience is the social factor. The supportive attitudes of friends and family were mentioned as a factor of influence, either via social norms growing up, “my family … have always shopped second hand”, or through the approval of friends “who like her style”. Notably, while several participants reported various people they know might disapprove of their secondhand clothing purchases, only one raised judgmental attitudes as a barrier to purchase.

Some participants noted that “making it an outing with friends” encourages them to buy secondhand, while others stated that people who approve are her “friends cause we’re always finding cool stuff to DIY [do it yourself] and style. It’s also fun to go to op shops with your mates” (

Figure 1). This understanding of secondhand shopping as a social activity reflects existing research that demonstrates that young women like to shop together [

63] and that they are more likely to purchase something when they do so [

64,

65,

66]. This shopping is important as both a social activity and a form of identity formation and exploration [

67]. These points further concur with the responses concerning social norms in which friends and peers were reported as more likely to approve than disapprove of secondhand clothing purchases (see

Table 2).

3.2. Factors That Influence Spontaneous Buying of Secondhand Clothing

As prototypes have been shown to influence people’s willingness [

23], it is a useful initial step to understand these prototypes more by undertaking pilot work for key descriptors of the prototype images. Therefore, the present research included questions to explore prototypes; in this case, the images of a woman who buys secondhand clothes and a woman who does not.

The perceptions of participants towards women who purchase secondhand clothing were overwhelmingly positive and could be broken down into four major categories: environmentally conscious, admirable character, admirable style, and money conscious. Four minor categories also present included progressive, age-related, have time, and other (

Table 3).

Unsurprisingly, following the findings regarding environmental impact advantages, words such as “eco-friendly”, “organic”, and “sustainable” were frequently deployed to describe women who purchase secondhand clothing. As discussed, when describing advantages, the positive environmental impact of purchasing secondhand clothing is a driving factor behind its growing popularity, so users are expected to have some level of environmental conscientiousness.

Under the category of ‘admirable style’ were words related to style such as “unique”, “fashionable”, “creative”, or “cool”. Of these, words related to uniqueness were the most frequently mentioned, with participants using alternate descriptions such as “funky”, “quirky”, “eclectic”, as well as “unique”. Here again, a connection can be made between these descriptions and the previously mentioned advantage of clothing. Participants strongly believed that an advantage of secondhand shopping was the uniqueness of the clothing, and they applied the attribute to its wearers.

The third most popular category was being money-conscious. Via phrases such as “thrifty”, “frugal”, and “financially responsible”, respondents usually positioned such behaviours in a positive light and as the buyer’s choice. However, some responses framed buyers less positively with phrases like “less well-off financially”, “broke”, or “poor”. This finding suggests there is still some stigma around the financial security of purchasers. It is interesting to note that while the cost of secondhand was the primary facilitator and second most mentioned advantage, it was less prominent in the prototypes.

Words such as “thoughtful”, “resourceful”, “confident”, “adventurous”, and “genuine”, which relate to a woman’s character, were grouped under the theme of ‘admirable character’. With the present popularity of secondhand clothes shopping and the positivity surrounding it, especially related to the environmental and social impact purchasing used clothing can have, it is unsurprising that most participants view women who assist in this positive impact as generally ‘good’ people.

Minor categories are progressive, age or life stage descriptions, having time, or other comments. Progressive descriptions incorporate responses related to being “politically progressive” and “wanting to make a difference”. Life stage or age-related descriptions centred on these women being young or being students, which also relates to an expectation that these people have free time to shop secondhand. These descriptors reflect the general perception that women who purchase secondhand clothing are trying to save money due to their life stage, being young and studying, or in the early phase of their career and therefore on a limited income but potentially having more free time. The other category includes phrases like “regular”, “normal”, and “me”, the latter being an indicator that respondents identify closely with such descriptions.

When participants were asked to describe women who do not buy secondhand clothing, negative, neutral, and positive perceptions surfaced. Assessments of character and style appeared again, but these descriptors were not necessarily positive (See

Table 4). Overall, negative perceptions of women who do not purchase secondhand clothing dominated, with neutral terms having the second highest number of responses.

Looking at the negative responses, being materialistic was the most frequent descriptor, with comments such as “brand lover”, “fast-fashion fiend”, “consumerist”, and “wasteful”. Disdainful descriptions captured responses such as “stuck-up”, “snobby”, and “judgemental”, while trend follower is a critique of both style and character, capturing comments like “only cares for trends”, “follower”, and the insult “basic”. Finally, just as individuals with higher levels of environmental consciousness are more likely to engage in sustainable fashion practices [

68], with descriptions like ‘little care for the environment’ or ‘not socially or environmentally aware’, participants frequently suggested those who did not purchase secondhand clothing had low levels of environmental consciousness.

The neutral sub-theme is dominated by a presumption of the socio-economic class of non-buyers, which is reflected in responses describing these women as “rich”, “upper class”, or “professional”. This theme, alongside the descriptor of “older”, positions non-buyers in opposition to the young, broke students who are secondhand clothes buyers. Explicitly neutral terms such as “average” and “regular” were also used by participants.

Lastly, positive comments describing women who do not buy secondhand clothing fall into images of fashionability, such as “stylish” and “trendy” or meticulous, including “very selective of clothing and styles”, “particular”, or “clean”. Overall, these descriptions suggested very specific images of women who do and do not buy secondhand clothes, and these images are frequently directly in contrast with each other. Understanding and intervening in this binary via messaging and market segmentation by retailers may enable them to expand their customer base and activity further.

Prototype image perceptions of secondhand buyers were almost uniformly positive in this age group (

Table 3). This finding is not unexpected as the buying of secondhand clothing is more widespread among women compared to men and can be found more frequently in younger than in older population segments [

69,

70,

71]. This perception is replicated in the subjective norm responses in which older relatives are specifically mentioned as being likely to disapprove and younger generations identified as likely to approve (

Table 2), and it is also visible, to a lesser extent, in the images of women who do or do not buy secondhand. Crucially, the unique or creative fashionability of these young women is described differently than the trendy or stylish fashionability of the “wealthy” or “older” woman who does not buy secondhand. This difference suggests a vital difference in how an admirable style is presumed to manifest in different age demographics in the minds of the young women participating in the study and the value of incorporating PWM in such studies. The consideration of such factors suggests several implications for theory-informed strategies to encourage sustainable consumption of clothing.

4. Conclusions and Implications

Reflecting the fact that “environmentally sustainable behaviour is influenced by multiple motives and determinants, which include internal, social, situational and demographic factors” [

72], this research has established some of the various overlapping perceptions and attitudes towards secondhand clothing and the young women who purchase it. Its key contribution is providing an additional nuance and complexity to existing discussions and demonstrating the value of adding the dimensions of prototypes found in the PWM to the TPB in studies of secondhand clothing.

Generally, the theoretical frameworks produced a wide variety of responses covering a range of broad perspectives about secondhand clothing, including those raised in previous research. However, there were some themes raised that did not naturally fit the established constructs of the selected models and point to areas for theory development in this context. The issue of the complexity inherent in business models of secondhand clothing operators (overpricing and not servicing lower-income consumers) showed that the coverage of beliefs of the Theory of Planned Behaviour is not able to always accommodate more complex ideas requiring a nuanced consideration of issues such as those related to pricing and ethical responsibility in the present study. While the issue may not be the perceived elevated costs itself, it is the expectations of pricing relative to what can be provided by fast fashion clothing retailers. Thus, merely referring to cost does not adequately capture the perspective of some consumers and does not fully reflect their underlying beliefs.

Second, the Prototype Willingness Model’s conceptualisation of images is not uniformly sufficiently developed to integrate notions of fashionability that vary based on specific age cohorts and associated expectations of fashion suitability. Images that allude to being fashion-conscious are delineated by age, such that fashion appropriateness for one age cohort may not be deemed favourable for another age cohort. The applied implications of these two domains are addressed in further detail below.

4.1. Conflicting Expectations: Research Implications for Retailers

The findings of the present research provide useful information for retailers to apply and prompt consideration of further strategies to encourage sustainable purchases. While the demand for secondhand garments is expected to grow three times faster than the overall clothing market by 2026, this increased uptake needs to be facilitated by consumer education and retail investments, which make purchasing secondhand more accessible and convenient than buying new [

3] (p. 88). This is particularly pertinent for Australia, which has one of the highest rates of secondhand clothing donation rates in the developed world, with a garment being ten times more likely to be donated to a charity retailer to be sold than be given as a hand-me-down or sold by the owner [

5].

The impact of the retail environment on sustainable consumption practices needs to be carefully considered. This factor was omnipresent as an element that determined the purchase of secondhand clothing. The frequency of mentions and types of comments found in the results might be particularly useful for charity store operators and online platforms to make note of, and it may inform plans for improvements and developments to appeal to new target markets. However, such changes should not be applied indiscriminately with the expectation of improved customer satisfaction and activity.

As noted in the findings, while some participants explicitly want their secondhand retail experience to mimic the experience they have when purchasing new clothes, being greeted by a well-organised store that smells nice and is air-conditioned, with the additional benefit of purchasing good quality and unique clothing for a fraction of the cost, critical examination of the responses indicates some prefer the status quo, dismissing “secondhand stores that try to act like an actual store” in favour of the “treasure hunt” and “taking the time to rummage through”. This suggests that rather than trying to appeal to everyone, more conscious and explicit differentiation in the secondhand retail experience might be productive. We can see this differentiation playing out in the online retail market, with mass retailers like eBay or Depop providing a very different experience and stock to high-end resellers focused on vintage and designer wares like 1stDibs or TheRealReal. This differentiation could equally be applied to brick-and-mortar stores.

Providing more variety in the market positions of stores, with some stores prioritising rummage bins and discount racks and others a more polished boutique feel, could address these conflicting desires. It is important to explain these various business models to consumers to help align expectations with experience and potentially come up with a tiered naming system that reflects the different store styles and priorities. Such messaging and educative work will also help ensure that customers may be willing to pay the price tag that comes with the additional sourcing, sorting, and merchandising costs of a more curated retail experience.

Following this, the type of retail experience participants seem to associate with secondhand clothing relates to perceptions of secondhand clothing and the need to change how it is valued. While secondhand clothes do not have material costs, the labour to collect, sort, and resell secondhand clothing is undervalued [

28] and frequently invisible or conducted by volunteers. The influx of low-value “fast fashion” into the secondhand market and the fact that prices for new clothes are currently the lowest they have ever been is squeezing the profits of secondhand retailers while at the same time damaging perceptions about the quality and diversity value of secondhand clothing. Educative work regarding the material, time, and labour costs that both go into its original construction and prepare it for resale and reuse is critical to move the needle regarding how these clothes are valued. Using social media to demonstrate the labour-intensive nature of such ‘behind the scenes’ work and inform about what “quality” looks like in a fashion product can enable retailers to connect with their younger consumers while helping to shift secondhand clothes’ perceived value. This education could further potentially improve what is donated and, further up the consumption chain shift, what is bought in the first place.

4.2. Conflicting Identification: Research Implications for Purchasers

The ways that perceptions of age and fashionability intersected in participant responses suggest a vital difference in how an admirable style is presumed to manifest in different demographics in the minds of the young women participating in the study. The concern raised by this demographic association is addressing the marketing challenges of making sustainable consumption of clothing via secondhand clothing mainstream in other age brackets.

As well as expanding the proportion of secondhand consumption in other demographics, crucially, such responses might imply that young buyers think of secondhand clothing as something they will ‘age out’ of as their spending power or time commitments increase. Secondhand shopping was perceived as cheaper but taking more time and effort, particularly in the difficulties finding a particular sought item rather than browsing and responding to available stock. Currently, it is expected that behaviours learned or undertaken in one life stage will continue in later life [

73], hence the focus on shifting the behaviours of young consumers whose lifetime consumption patterns will have a long tail. Here again, there is educative work to be undertaken to make purchasers conscious of this implicit bias via messaging to challenge this assumption. Consistent with the point made above regarding developing different retail experiences, these could be targeted to appeal across different demographics (e.g., with some stores operating at a lower price point and featuring more casual clothes and others reducing the time burden and effort associated with secondhand clothing and providing a more formal product mix). These strategies to differentiate the store’s market position could help to ensure that secondhand clothing’s appeal does not wane with age and lifestage.

4.3. Study Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

This research has provided insight into young Australian female perspectives on barriers to sustainable fashion consumption via purchasing secondhand clothing. This survey generated rich and detailed responses from participants, while multiple iterations of coding within the research team refined the findings and results. Drawing on established decision-making models provides a strong theory base to develop the findings going forward to test the more direct predictors of secondhand clothing consumer behaviours among young women and additional productive models to incorporate. The identification of two additional domains outside of the employed theoretical frameworks, however, highlights the need to consider other conceptual approaches to representing young women’s perspectives of secondhand clothing purchasing that could include a consideration of the ethical obligations of retailers and fashion ideals attached to age expectations. Limitations in this research centre around the diversity of participants and the focus of the survey, as noted above in

Section 2.

Several productive areas of future research emerge from these scope limitations. The first includes an investigation of those not represented in our participants. Exploring men’s purchasing attitudes and behaviours is a worthy area of research, particularly as they are less likely to buy secondhand [

70] or employ sustainable fashion practices [

34]. Equally, incorporating individuals from different age groups will help identify if attitudes and intentions differ across generations as is currently presumed [

69]. Another aspect to be addressed is the potential geographic and cultural specificity of responses. A comparison with existing research on this topic conducted elsewhere in Australia [

31], in the USA [

32], France [

30], and Brazil [

33] establishes that many of the motivations and concerns about secondhand clothing purchasing are consistent across these studies. However, undoubtedly cultural values and social norms inform secondhand clothing purchasing patterns and intentions [

29,

32,

34,

74], so care must be taken regarding the general applicability of findings across cultures. As our study recruited participants from Queensland, Australia, the responses and analysis are shaped by this context. This ranges from the prosaic, such as the desire for in-store air-conditioning in a location known for its warm climate, to the cultural context in which charities dominate the Australian secondhand clothing retail market [

5,

75], with subsequent expectations about the moral value of such purchases. While we hope that our published data set may make such future research and comparison easier, we are conscious our findings might not be relevant to all contexts.

The second productive area of research is investigating the attitudes of people who use but do not purchase secondhand clothing. This survey specifically addressed purchasing behaviours but, as some respondents pointed out in their responses and concurring with Cruz-Cardenas et al. [

76], people can obtain and use secondhand clothing from other sources, such as gifts or swaps with friends and family. Such sources may negate the concerns about hygiene or previous owners or potentially shift perceptions of approval. Further exploring the nuances of this dissonance regarding sources of secondhand clothes could be a rich area of study.

Finally, it would be useful to test the importance of these elicited beliefs in a larger quantitative study to assess their role in influencing young women’s secondhand clothing purchases. Further, this examination could include a consideration of differences based on background factors such as residence and income level to establish if they interact with the identified beliefs and model constructs.

Overall, this study’s theory-based exploration of young women’s attitudes and perceptions concerning the purchase of secondhand clothing allows a timely reflection of people’s contributing cognitions. Understanding these underlying beliefs is essential in retail efforts to encourage sustainable purchasing behavioural patterns among current and future generations of consumers, complementing recent policy imperatives globally to reduce textile waste.