Abstract

Waste segregation at the source is one of the most important strategies of urban waste management and the first environmental priority. This systematic review study was conducted to determine the effects of various interventions to promote household waste segregation behavior. Studies were searched in the Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed databases using the keywords “waste segregation, intervention, randomized controlled trials, and clinical trials”. Through 2 January 2022, two researchers were independently involved in article screening and data abstraction. Inclusion criteria were as follows: experimental and quasi-experimental studies where primary outcomes of the studies included improvement in waste separation behavior, and secondary outcomes of the studies included increased knowledge and improvement in psychological factors. Articles that did not focus on households, studies that focused only on food or electronics separation, and studies that focused only on recycling and its methods were excluded. Of the original 5084 studies, only 26 met the inclusion criteria after reviewing the titles, abstracts, and full texts of the articles. The age of study participants ranged from 15 to 82 years. It seems that most of the studies that suggest higher efficacy consider older age groups for the intervention. Positive results of the interventions were reported in all studies with different ratios; in five studies, the improvement in results was more than 20%. Meta-analysis was not possible because of the diversity of study strategies and outcomes measured. In the studies that lasted longer than two months, people’s waste separation behavior was more permanent. Approaches such as engagement, feedback, and theory-based interventions have been effective in promoting waste separation behavior. Interventions that considered environmental, social, and organizational factors (such as segregation facilities, regular collection of segregated waste, tax exemption, and cooperation of related organizations) in addition to individual factors were more effective and sustainable. For the comparison of studies and meta-analysis of data, it is suggested to use standard criteria such as mean and standard deviation of waste separation behavior and influential structures such as attitude and norm in studies. The results show that it is necessary to use environmental research and ecological approaches and intermittent interventions over time to maintain and continue waste separation behavior. Based on the results of the current research, policy makers and researchers can develop efficient measures to improve waste sorting behavior by using appropriate patterns in society and knowing the effective factors.

1. Introduction

One of the biggest environmental problems worldwide is the high volume of waste, especially in developing countries, which has become a major challenge. Solid waste management involves various types of environmental, economic, social, production, collection, transportation, treatment, and disposal problems. Therefore, cost-effective and environmentally friendly solutions for them should be considered [1,2]. According to the World Health Organization reports, about 23% of all deaths worldwide are related to the environment (about 13.7 million deaths per year), which could be prevented by creating a healthier environment. In addition, a healthier environment can prevent about a quarter of the world’s diseases [3]. Improper waste disposal leads to human deaths from cancer and birth defects [4]. It also leads to death from lung cancer and respiratory diseases in adults and children [5].

Solid waste management affects everyone in the world. On average, 0.74 kg of waste is generated per person per day worldwide. By 2050, global waste generation is expected to increase by 70 percent from 2.01 billion tons of waste in 2016 to 3.40 billion tons of waste per year [1]. In 2018, the total amount of municipal solid waste generated was 292.4 million tons, of which only 38.2% by weight was managed mainly through mechanical recycling and composting. Of the remaining quantities, 11.8% was incinerated for energy recovery and 50%, i.e., 146 million tons, was buried [6]. The main problem of waste generation is related to environmental hazards such as water and soil pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, which have many negative effects on the quality of life of all organisms [1,7].

The most important solid waste management measures are recycling, which leads to economic savings and conservation of environmental resources [8]. Waste management systems have developed in most countries [9]. In industrialized countries, more than half of all waste generated is returned to the natural cycle through recycling, composting, and incineration (energy generation). However, in low-income countries, only 4% of all waste is recycled and composted, and most waste is disposed of in open landfills [1]. Many cities in developing countries lack adequate drainage and waste disposal infrastructure. As a result, urban dwellers face the economic and health impacts of flooding and inundation, which are exacerbated by the infiltration of solid waste and the blockage of drains [10]. In the European Union (EU), 3.3% of respondents stated that they do not sort waste at all [11]. However, in some countries, less than 30% of waste is recycled [12,13].

Recycling requires separation of waste at the source, which is an essential part of an integrated solid waste management system [1]. Solid waste management includes various components, such as waste generation, collection, transportation, recycling, and disposal, and its hierarchy includes the following: reduction, reuse, recycling, energy recovery, and accessibility. Waste treatment and disposal includes recycling, composting, anaerobic digestion, incineration, landfilling, open dumping, and discharge into marine areas or waterways [1,14]. Waste separation and composting can divert about two-thirds of household waste from landfills [9]. Waste recycling helps to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases and pollutants and is considered an effective way to achieve economic growth using separated resources [15]. However, national composting and recycling rates are low in many parts of the world.

Social and behavioral scientists recognize that waste separation behaviors at the source are multifaceted. Transforming problematic behaviors, such as burning or throwing away waste, into environmentally friendly actions, such as dedicated waste separation and recycling, requires creative and sustained efforts by influential factors [9]. Although an infinite number of variables can influence behavior in some way, only a small number of variables need to be considered to predict, change, or reinforce a particular behavior in a given population [16]. This underscores the need for in-depth preliminary research to identify the key drivers and barriers to recycling in households [17]. To achieve this goal, governments need to create a high level of public participation in the separation of waste at the source among citizens, encourage them to do so, and identify the factors that influence the separation of waste [18].

The results of one study showed that attitudes, subjective norms, and self-efficacy have a significant influence on the intention to separate waste [19]. In another study, the incentives for waste separation were ensuring that waste does not accumulate after collection and the availability of nearby composting facilities [20]. The use of campaigns can also lead to community participation; however, more sophisticated strategies are needed to translate behavioral intentions into normal behavior [9].

For some interventions, the following models and theories were used to improve waste segregation behavior. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is an individual theory consisting of the constructs of attitude, norm, perceived behavioral control, and intention. The Integrative Model of Behavior Prediction (IMBP) is also a model that has all the structures of the TPB and also recognizes the role of environment, skills, and abilities in moderating the relationship between intention and behavior. Its main premise, as with TPB, is that when people perform a behavior that is positively valued (attitude), they believe that important others want them to do it (subjective norm), and that they believe this behavior is under control (perceived behavioral control). The most important determinant of behavior in these two models is the intention to perform the behavior. Without motivation, it is unlikely that a person will perform the recommended behavior [21,22,23].

The Health Belief Model (HBM) assumes that people will engage in a health behavior or take a recommended action if they believe that an action poses a potential threat and could have serious consequences. Its constructs are perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits and barriers to engaging in a behavior, cues to action, and self-efficacy [22].

Bandura’s social cognitive theory (SCT) is one of the theories of behavior change that combines social structural factors with personal dimensions. This theory predicts, explains, and changes behavior in different situations. The constructs of this theory are knowledge, outcome expectations, outcome values, situational understanding, environment, self-efficacy, self-efficacy in overcoming obstacles, self-control, and emotional adjustment [21,22].

Risks–Attitudes–Norms–Abilities–Self-regulation (RANAS) is a model for behavior change. This model assumes that behavior and habit formation are related to five risk factors, attitudes, norms, skills, and self-regulation. Therefore, by developing and evaluating behavior change strategies that target behavioral factors, it is possible to change a specific behavior in a specific population [24].

To date, various intervention studies have been conducted worldwide, which require a comprehensive, complete, and systematic review of the available studies to identify effective interventions. Previous systematic studies had inclusion criteria such as limited years, social marketing approach, food waste [9,17,25]. In the systematic study by Kim et al. [25], only the studies based on the social marketing approach were examined. The Varotto study was limited to the years 1990 to 2015 and considered studies conducted in industrialized countries [17]. Other studies have examined the health consequences of exposure to waste [26,27]. These criteria meant that a large number of interventions were not investigated. The aim of our study was to close this gap. That is, all intervention studies should be reviewed regardless of history, language, culture, region, and socioeconomic status. Therefore, this systematic review was conducted according to the impact of interventions and existing deficiencies to determine the impact of interventions and to identify the most appropriate interventions, strategies and theories. Our aim was to identify the most effective experimental interventions to promote waste separation in households.

The research questions are as follows:

RQ1. What is the quality of existing studies in the area of waste segregation interventions?

RQ2. What are the interventions to improve waste separation behavior?

RQ3. What is the impact of interventions to improve waste separation behavior?

RQ4. What is the impact of the variables studied on the interventions implemented to improve the waste separation behavior?

RQ5. What intervention strategies exist based on health education structures to improve waste separation behavior?

RQ6.What effective health promotion models exist to promote waste separation behavior?

For a general understanding of the interventions, we need to know their quality; find their practical strategies and methods in different societies; know the ecological levels used (individual, environmental, organizational, and social); find the strategies based on the structures, models, and theories of health education used in the studies; know the variables of the different studies; find the effect of interventions on waste separation behavior; identify the most effective interventions; and identify the main influencing factors. By summarizing these results, we can understand people’s waste separation behaviors and design and implement effective interventions.

2. Methods

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines were used to conduct this systematic review and report the results [28]. Articles were retrieved from databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus. The search was performed until 2 January 2022, with no restriction on the language or year of publication of the articles. To update the data on 1 November 2023, the PubMed database was searched with the search terms and the extracted articles were reviewed.

2.1. Search Strategy

The search strategy was based on a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MESH) terms. The key terms included in the search strategy were “Recycling” OR “Waste” OR “Waste Segregation” OR “Household Waste segregation” OR “Source segregation” AND “experimental studies” OR “Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic” OR “Non-Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic” OR “randomized clinical trial” OR “non-randomized clinical trial” OR “Intervention” OR “Education” OR “Behavioral theories” AND “House wives” OR “Women” OR “Woman” OR “Girls” OR “Household”. The search strategy in the PubMed database was performed according to Supplementary Materials, and necessary changes were made according to the necessity in each of the databases.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The studies were included based on the population, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) inclusion criteria.

Population: The target audience was households, regardless of race or residence in any region of the world. Articles that did not focus on households were removed.

Intervention: All experimental and quasi-experimental studies that implemented at least one intervention to promote waste separation (educational or non-educational) were included. Reviews, letters to the editor, and studies that focused only on food or electronics separation were excluded. In addition, studies that focused only on recycling and its methods were excluded.

Comparison: The comparison group consisted of households excluded from the intervention.

Outcome: Primary outcomes of the studies included improvement in waste separation behavior, and secondary outcomes of the studies included increased knowledge and improvement in psychological factors (such as attitudes, norms, beliefs, motivation, and self-efficacy).

Three databases were searched based on keywords. After database searches were completed, articles were entered into EndNote.

2.3. Data Extraction

First, the titles and abstracts of the studies found through the electronic search were independently reviewed by the two coauthors (M.H., Kh.ER.) for suitability, then all retrieved articles were entered into the EndNote 20 software. Duplicates were then removed in EndNote. The titles, abstracts, and texts of the relevant studies were independently reviewed by two researchers (M.H. and Kh.ER.) for relevance to the research question and based on the inclusion criteria. It should be mentioned that the third researcher (B.M.) clarified any discrepancies. After the final articles were identified, the list of all their references was reviewed and the articles that were also given to these articles by the site were reviewed in databases. Finally, three articles were added to the final articles. Since the number of articles was not available, the central library was referred to, and the full text of the articles was received and reviewed.

2.4. Quality Assessment

The quality of the studies was assessed using the Cochrane group [29], which rated the available studies based on six items. However, we used five items (i.e., randomization, randomization method, blinding, blinding method, and excluded samples) because of the diversity of the studies. Seven investigators performed this process independently. Five criteria were assessed using the checklist.

Each item was given a score of 0 or 1. A score of 1 was received if the relevant item was properly reported, and a score of 0 was given if the relevant item was not reported or was an inappropriate report. The maximum scale score is equal to 5 and a higher score in this scale indicates the quality of the article’s reporting. The quality scores ranged from 0 to 5, and the articles with a score of 4–5, 2–3, and less than 2 were classified as high, medium, and low in terms of quality, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Initial Search Results

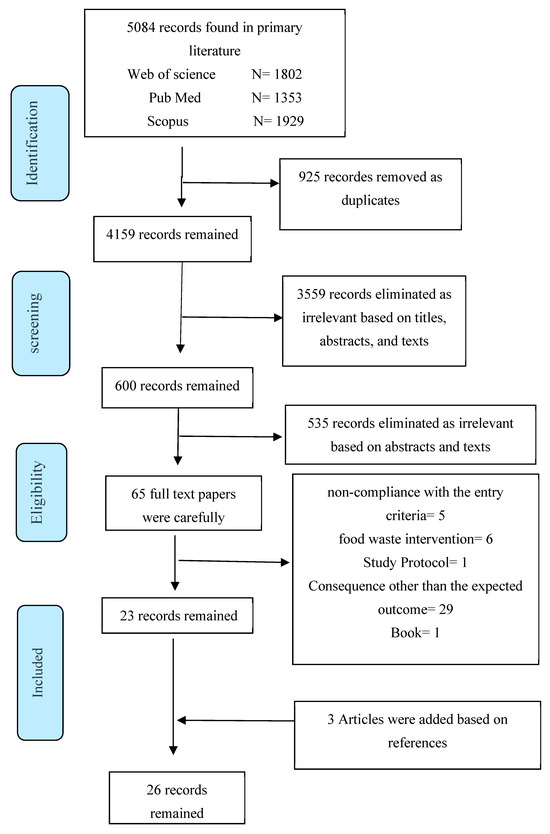

The initial search found 5084 articles, of which 925 articles were deleted due to overlap. Accordingly, 4159 articles remained, the title, abstract, and texts of which were studied independently by two researchers. Finally, 65 articles were considered eligible for the study, and a total of 26 studies remained. The process of study selection is shown in Figure 1. After updating, 271 new articles were found. After checking the title and abstract, 11 articles remained. The full text of the articles was then reviewed. There were seven descriptive and analytical studies, two review articles, and two intervention articles among students. None of the articles met our inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of studies in the systematic review process.

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

Practical strategies in the interventions included the following: face-to-face training, lectures, focus group discussions, educational brochures, posters, education sessions, door-to-door visits, and persuasive communications. Moreover, strategies of encouragement, commitment, promotion, campaigns, radio training, providing garbage bags, weekly collection, access to and presentation of information tags, strengthening the building recycling system, informational websites, reminders and feedback, workshops, mobile applications, and local media were used (Table 1).

Table 1.

Applied strategies in waste separation interventions at the source.

The results of Figure 1 show that most studies took an individual approach. Face-to-face training, removing existing barriers by providing facilities (e.g., provision of facilities to separate waste in the home, regular collection of separated waste), and providing feedback were used more frequently. Encouragement and home visits were used less.

3.3. Outcome

3.3.1. Quantity of Studies

Among the 26 articles, 10 RCT studies, 5 quasi-experimental studies, and 11 pre-experimental studies were included. From the articles, information such as the name of the first author, country, year of study, type of study, sample size, gender of participants, intervention strategy, intervention details, variables, outcomes, and total quality score were extracted and listed.

The studies in this review were geographically diverse and broad, spanning all continents. Studies were conducted in the United States, Canada, New Zealand, England, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Iran, China, Lebanon, India, Indonesia, Singapore, and Mozambique. The total number of participants in these studies was 13,543 cases with an age range of 15–82 years. The participants of 7 studies were male and female, and 6 studies were conducted with female participants only; in 13 studies, the gender of the participants was not mentioned.

Two interventions accounted for the largest sample sizes (1000 and 6580) [34,40]. However, in two studies the number of participants was less than 100 cases [50,53], and in three studies it was 100–102 participants [43,45,49]. Most studies had a volume of 144–680 subjects.

3.3.2. Quality of Studies

In addition, six of the studies were based on a model or theory [24,31,42,43,52], and interventions were delivered by trained individuals, peers, and block leaders (Table 2). Applications and websites were also used [24,38,47], which improved waste separation behavior in all interventions. Behavioral criteria examined in the studies included the following: segregated ratio from the source, waste generation rate, recycling rate, participation rate, satisfaction rate, recycled waste composition, knowledge level, attitude, norm, perceived behavioral control, and self-efficacy.

Table 2.

Models and theories used in waste segregation studies.

The results in Table 2 show that more researchers have used theories and models in recent years. The individual TPB theory has been used in more studies. The constructs of attitude, norm, perceived behavioral control, and intention were used more frequently. In all these six studies, they first raised people’s awareness. Then, they tried to improve people’s waste separation behavior by increasing their sensitivity and changing their attitudes.

The interventions were carried out at different individual, interpersonal, organizational, and environmental levels. Based on the measurement indicators, the amount of waste separation has increased significantly in most of these studies. The measurement tools were a questionnaire and the weight of recycled materials. The duration of the measure ranged from a few days to 36 months, and the most practical strategy was face-to-face training.

Quality assessment was based on randomization, randomization method, blinding, blinding method, and excluded samples; accordingly, 12, 11, and 3 articles were classified as low, medium, and high quality, respectively. Agreement between the two investigators was determined using five components of the Cochrane tool [29]. There was good agreement among the researchers; however, there was disagreement in only 3 of the 4159 articles examined, i.e., they agreed 99% of the time, which is desirable. The quality measurement table can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

The objective of this systematic review was to determine the impact of interventions to promote waste separation behavior by identifying theories, practical methods, and effective strategies to promote household waste separation behavior. The interventions significantly increased the likelihood of household waste separation and reduced the amount of waste generated in households. They also increased knowledge and improved psychological factors, such as attitude.

Lack of waste separation is an environmental problem that has become a major challenge due to rapid urbanization and population growth. For smaller communities with lower economic levels, it is even more difficult to solve this problem [54]. Waste recycling helps to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases and pollutants. Reusing existing materials saves resources and energy, reduces pollution, and reduces the need for regular waste disposal [17]. Therefore, educational activities and encouraging citizens to actively participate in waste sorting are recommended to increase their awareness and empowerment [12]. However, more advanced strategies are needed to translate behavioral intentions into normal behavior [9,46]. Studies have shown that the use of health education strategies can improve waste sorting behavior [43,50,52]. The main components of health education come from the behavioral sciences, and health promotion is deeply rooted in the social sciences. On the other hand, the main concepts of the behavioral and social sciences are organized in the form of theories and models [21]. Many variables influence waste separation behavior, such as social and behavioral factors. Knowing the variables requires understanding human behavior in this field. Effective strategies can be developed by understanding people’s behavior. Innovative strategies, as well as the application of behavior change theories, can have a positive impact on recycling and overall waste reduction behavior [43].

4.2. Effective Models and Theories

According to the researchers’ classification, of the 26 available studies, 6 studies used models and theories of health education and health promotion for the effect of educational interventions on households [24,31,38,42,43,52]. These theories and models included the theory of planned behavior, integrated behavioral model, norm activation model, health belief model, RANAS model, and community-based social marketing approach along with social cognitive theory and the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Based on the measurement indicators, these studies increased the amount of waste separation. Of course, it was found that the TPB and its constructs were used more than other models and theories. In many studies, attitude, norm, perceived behavioral control, intention, and environment were among the most important predictors of waste separation behavior [8,18,19,55,56]. Of course, the two systematic studies by Kim et al. [25] and Sewak et al. [9] focused on examining the effectiveness of the social marketing approach and did not examine the effects of other interventions. They also showed that behavior change was more likely when social marketing components were used more.

The results show that individual theories are effective for waste separation behavior. These theories increase people’s awareness by focusing on the individual. By creating a positive view of the beneficial consequences of behavior, they motivate people. Motivation leads to behavior when the opportunities are present. Therefore, with this type of intervention, it is possible to improve waste sorting behavior by removing barriers.

4.3. Effectiveness of Interventions

Numerous studies have shown that waste segregation interventions at the source are effective [10,17,25,57,58,59,60]. Some studies had a multi-group intervention group, with different strategies for each group to improve waste separation behavior [30,32,35,37,40,41]. The review of studies shows that elderly people show pro-environmental behavior, the effectiveness of intervention is greater in older age groups, and the younger generation is less inclined to recycle [61,62,63]. This seems to be the reason why most studies consider older age groups for intervention.

The study of the results has shown that a small intervention in waste separation arouses people’s curiosity and behavioral intentions. The most reported result in the field of improving waste segregation behavior was related to a study conducted by Born with an increase of 30%, followed by studies carried out by Karimi (24.2%), Shan (20%), Flygansvær (19%) and Zand (63.9%). Varotto’s meta-analysis showed that different types of measures improve recycling behavior over the duration of the measure [17]. Therefore, the behavior improves through various educational and environmental interventions. However, personal training and the provision of facilities have a greater impact on the initiation of the behavior and its continuation. Maintaining and promoting this behavior does not require high costs. Basic facilities such as the provision of waste garbage cans for dry waste and regular door-to-door collection of dry waste can significantly increase the amount of waste separation.

4.4. The Effects of the Measurement Period

The duration of assessment was short-term (less than 2 months) in most studies, followed by medium-term (2 to 6 months) [24,31,34,40,41] in some other studies, and long-term (annually) in some studies [13,42]. Interventions that lasted less than 2 months had a good initial effect and increased waste separation. But, after some time and without reminders, this behavior decreased. Some studies lasted more than two months, and the reminders were also used after the end of the intervention. In these studies, people’s waste separation behavior was more stable and became habitual for some of them. The review of the studies showed that waste separation behaviors are among those that take time to become permanent. Therefore, it is recommended to implement these programs intermittently and over a longer period of time.

4.5. Measuring Tool

The measurement tool in most studies was a combination of a questionnaire and measurement of the weight of recyclable materials. However, some studies used only questionnaires and self-reporting. Using a questionnaire and measuring the weight of recyclable materials certainly increases the validity of the study results, as self-reporting increases the probability of error. In several studies, the composition of recyclable materials was measured, and the highest amount included paper and cardboard, newspaper, plastic, and glass; moreover, clothing and rubber were included, which were the lowest-amount groups [13,49,53].

4.6. Intervention Strategies

The review showed that some studies focused solely on individual factors [45,48,51,53]. Many factors are effective at preventing waste separation behavior, such as lack of motivation, awareness, time, and positive attitude, which can be solved by providing appropriate training [12,31,64]. Approaches such as commitment, feedback, and theory-based interventions have been effective in promoting waste segregation behavior. The key strategies used in some studies included training sessions or making facilities available. Campaigns were used in two studies [39,46]. Evidence showed that norms played an important role in improving segregation behavior [31,38,44]. In two studies, researchers used mobile applications [24,47], and in a few others, they used commitment or feedback to teach topics that had a significant effect on improving waste segregation behavior. Face-to-face training has also been effective in increasing waste segregation behavior. Meta-analysis was not possible because of the diversity of study strategies and outcomes measured.

The review and analysis of studies showed that waste segregation behavior requires different strategies, and the studies that used different individual, social, and environmental strategies were more effective. The provision of facilities for waste separation at the place of residence, regular collection of separated waste, tax exemption, the use of social groups, and cooperation with related organizations were influential factors in this area. Therefore, it is recommended that these programs be performed intermittently and for a long time.

Various studies have identified the determinants of waste segregation, including individual factors (e.g., knowledge, self-efficacy, and motivation), interpersonal factors (e.g., social support, norms, and practices), organizational factors (e.g., municipal support), environmental factors (e.g., making facilities available), and community factors (e.g., insufficient awareness of the importance of waste segregation as a social norm and ignorance of existing programs) [9,12,18,19,31,55,56]. At the individual level, face-to-face training and raising awareness were effective. Regarding the interpersonal level, education through peers, as well as neighbors and feedback, were considered important. Furthermore, providing equipment and facilities was crucial at the environmental level and at the community level; using applications and passing laws or media support was effective to influence waste segregation behavior. The provision of facilities for waste separation at the place of residence, regular collection of separated waste, tax exemption, the use of social groups, and cooperation with related organizations were influential factors in this area.

4.7. The Most Effective Interventions

Waste separation behavior in the countries studied was not the same. While in some countries there is individual and social responsibility for this issue, this is not the case in other countries. The reason for this could be a lack of suitable infrastructure. For example, there is a lack of the necessary training in this area and facilities for product separation. The most effective solutions in low-income countries were education and the provision of environmental facilities. In high-income countries, on the other hand, the obligation and collection of taxes and additional fees for more waste was an effective solution. It seems that the economic and political situation of countries is one of the most influential factors in this area. Earlier studies have come to similar conclusions [1,65,66,67,68]. The results of Duan’s study show that the social level, the technological level, and the level of awareness have a positive influence on recycling [15].

Combined individual, interpersonal, and environmental approaches that have higher frequency and a longer duration were the most effective ways to improve waste segregation. These approaches used face-to-face training along with making commitments, training by peers, providing feedback, and providing environmental facilities. Face-to-face training, feedback, and raising awareness using different media were the most widely used methods to improve waste segregation. The methods of face-to-face training, obtaining commitment, providing feedback, environmental facilities, and using different media caused the most participation of the participants in waste separation behavior. A systematic review study conducted on the best way to reduce food waste showed that personal interaction strategies were the most effective technique of the programs [25].

The results show that it is necessary to use environmental research and ecological approaches and intermittent interventions over time to maintain and continue waste separation behavior. The provision of facilities for waste separation at the place of residence, regular collection of separated waste, tax exemption, the use of social groups, and cooperation with related organizations were influential factors in this area. This systematic review can pave the way for researchers and policy makers to plan, design, and implement waste separation measures by identifying practical strategies and effective practical solutions.

4.8. Strengths and Limitations

One of the strengths of this study is that all articles from the three main databases were reviewed without language or time restrictions. Another advantage was that the studies in this review were geographically diverse and broad, covering all continents. All studies conducted in all countries with different cultures, environments, economies, and societies were examined. This expansion led to the identification of very different and effective strategies and solutions for waste sorting behavior. This geographical diversity of the studies increases the external validity of the results.

Limitations of the study were that the intervention group consisted of multiple groups and that some studies did not adequately explain the implementation method and results. The limitations of the methods used in the studies may limit the generalizability of the results. In addition, the inconsistency of the reported results made a comparison of the quantitative results and a meta-analysis impossible. The short-term nature of many assessments challenges their effectiveness. The effect of the interventions in these studies is an immediate and momentary effect that is transient. This effectiveness may have changed over time, which was not investigated. In most studies, demographic variables such as age, gender, and income status were not mentioned. Therefore, the effect of demographic variables was not investigated. We acknowledge that studies may have been overlooked when updating the data, which only came from the PubMed database. However, it is highly likely that the selected articles in the study are representative of all studies. This is because they were extracted from three main databases without any restrictions.

4.9. Future Research

For the comparison of studies and meta-analysis of data, it is suggested to use criteria such as mean and standard deviation of waste separation behavior and influential structures such as attitude, norm, perceived behavioral control, and environmental factors in studies. In addition, if possible, the weight of recyclable waste and the percentage of people’s participation before and after the intervention should be calculated. Paying attention to these cases and research standards provides the opportunity to analyze studies.

The use of different research methods and their different consequences may be due to differences in cultural, social, and environmental conditions among countries and even among different regions of the same country, which requires further investigation. Therefore, for future research in different communities, we suggest first conducting qualitative research in the desired area. This should identify the individual, interpersonal, organizational, and environmental influencing factors. The study will then be designed and conducted based on the findings obtained. One should pay attention to the timing and frequency of the study when planning and conducting it, and involve different levels of the environment. Also, researchers should take advantage of support from governmental and nongovernmental institutions, nongovernmental organizations, and environmental advocacy organizations such as the community and environmental organizations.

Policy makers, waste management authorities, and municipalities can use the results of this study to design and implement effective measures. In addition, they can maintain and improve waste sorting behavior with ecological approaches at different levels and with different strategies, at different times, and with access to more resources through collaboration between different organizations.

5. Conclusions

Waste separation behavior varies from country to country. While in most countries there is individual and social responsibility for this issue, in some countries this is not the case. According to the literature review, this is due to the lack of necessary education in this area and the lack of necessary facilities for waste separation. Therefore, different age groups should be taught in these countries. This will increase their awareness and create a positive attitude among them, and at the same time environmental facilities and equipment should be provided. However, in countries with higher levels of awareness and recycling, other solutions should be adopted; for example, a policy of taxation for more waste generators and tax exemption for fewer waste generators.

The results of the systematic review have shown that the use of ecological approaches at different levels and intermittent interventions over time are necessary to maintain and continue waste segregation behavior. Approaches such as engagement, feedback, and theory-based interventions have been shown to be effective in promoting waste separation behavior. Some interventions have considered environmental, social, and organizational factors in addition to individual factors and have been shown to be effective over time. Therefore, interventions with different strategies, temporal variations, and access to more resources through collaboration among different organizations are needed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su152416546/s1. Table S1: shows the search strategies used to find articles in the three main databases; Table S2: shows the study quality based on five elements of the Cochrane group; Table S3: shows a summary of interventions to improve waste sorting behavior in 26 remaining studies; Table S4: shows the PRISMA 2020 checklist.

Author Contributions

B.M.: conceptualization, methodology, disagreement review, checking the quality of articles, review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition from the university. E.A.: conceptualization, methodology, extracting articles, supervision, checking the quality of articles, review and editing. S.B.: conceptualization, methodology, checking the quality of articles, review and editing. M.B.: conceptualization, methodology, checking the quality of articles, review and editing. L.T.: conceptualization, methodology, checking the quality of articles, review and editing. K.E.-R.: conceptualization, methodology, extracting articles, review articles, checking the quality of articles, writing—review and editing. M.H.: conceptualization, methodology, extracting articles, review articles, checking the quality of articles, writing—review and editing, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was financially supported by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. The researchers are independent of the funders. The funding body did not take part in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or preparation of the manuscript (Grant number: 140010148499).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences with proprietary ID, IR.UMSHA.REC.1400.755.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. Because this is a systematic review study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the cooperation and financial support of the Vice Chancellor for Research of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences and all the people who collaborated with the research group in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Kaza, S.Y.; Lisa, C.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Van Woerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050. Urban Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/30317 (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Pires, A.; Martinho, G.; Rodrigues, S.; Gomes, M.I. Sustainable Solid Waste Collection and Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Prüss-Ustün, A.; Wolf, J.; Corvalán, C.; Neville, T.; Bos, R.; Neira, M. Diseases due to unhealthy environments: An updated estimate of the global burden of disease attributable to environmental determinants of health. J. Public Health 2017, 39, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triassi, M.; Alfano, R.; Illario, M.; Nardone, A.; Caporale, O.; Montuori, P. Environmental pollution from illegal waste disposal and health effects: A review on the “Triangle of Death”. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1216–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mataloni, F.; Badaloni, C.; Golini, M.N.; Bolignano, A.; Bucci, S.; Sozzi, R.; Forastiere, F.; Davoli, M.; Ancona, C. Morbidity and mortality of people who live close to municipal waste landfills: A multisite cohort study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sakkari, E.G.; Habashy, M.M.; Abdelmigeed, M.O.; Mohammed, M.G. An overview of municipal wastes. In Waste-to-Energy: Recent Developments and Future Perspectives towards Circular Economy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sadhu, S.D.; Garg, M.; Kumar, A. Major environmental issues and new materials. In New Polymer Nanocomposites for Environmental Remediation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Yu, A. The role of perceived effectiveness of policy measures in predicting recycling behaviour in Hong Kong. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 83, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewak, A.; Kim, J.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Deshpande, S. Influencing household-level waste-sorting and composting behaviour: What works? A systematic review (1995–2020) of waste management interventions. Waste Manag. Res. 2021, 39, 0734242X20985608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepal, M.; Karki Nepal, A.; Khadayat, M.S.; Rai, R.K.; Shyamsundar, P.; Somanathan, E. Low-cost strategies to improve municipal solid waste management in developing countries: Experimental evidence from Nepal. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2023, 84, 729–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minelgaitė, A.; Liobikienė, G. The problem of not waste sorting behaviour, comparison of waste sorters and non-sorters in European Union: Cross-cultural analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 672, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, E.; Solhi, M.; Farzadkia, M. Determinants of Sustainability in Recycling of Municipal Solid Waste: Application of Community-Based Social Marketing (CBSM). Chall. Sustain. 2021, 9, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousta, K.; Bolton, K.; Lundin, M.; Dahlén, L. Quantitative assessment of distance to collection point and improved sorting information on source separation of household waste. Waste Manag. 2015, 40, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Home, Publications, Overview, Compendium of WHO and Other UN Guidance on Health and Environment. Compendium of WHO and Other UN Guidance on Health and Environment, 2022 Update. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HEP-ECH-EHD-22.01 (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Duan, H.; Zhao, Q.; Song, J.; Duan, Z. Identifying opportunities for initiating waste recycling: Experiences of typical developed countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 324, 129190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yzer, M. The integrative model of behavioral prediction as a tool for designing health messages. Health Commun. Message Des. Theory Pract. 2012, 2012, 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Varotto, A.; Spagnolli, A. Psychological strategies to promote household recycling. A systematic review with meta-analysis of validated field interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Huang, G.; Yin, X.; Gong, Q. Residents’ waste separation behaviors at the source: Using SEM with the theory of planned behavior in Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 9475–9491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Kaur, R. Influencing the Intention to adopt anti-littering behavior: An approach with modified TPB model. Soc. Mark. Q. 2021, 27, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyatmika, M.A.; Bolia, N.B. Understanding citizens’ perception of waste composting and segregation. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2023, 25, 1608–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M. Theoretical Foundations of Health Education and Health Promotion; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Montano, D.E.; Kasprzyk, D. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. Health Behav. Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 70, 231. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, X.; Ang, W.L.; Yang, E.-H. Mobile app-aided risks, attitudes, norms, abilities and self-regulation (RANAS) approach for recycling behavioral change in Singapore. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 162, 105049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Knox, K. Systematic literature review of best practice in food waste reduction programs. J. Soc. Mark. 2019, 9, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, K.; Goldizen, F.C.; Sly, P.D.; Brune, M.-N.; Neira, M.; van den Berg, M.; Norman, R.E. Health consequences of exposure to e-waste: A systematic review. Lancet Glob. Health 2013, 1, e350–e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, D.; Milani, S.; Lazzarino, A.I.; Perucci, C.A.; Forastiere, F. Systematic review of epidemiological studies on health effects associated with management of solid waste. Environ. Health 2009, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burn, S.M. Social psychology and the stimulation of recycling behaviors: The block leader approach. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 21, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldeman, T.; Turner, J.W. Implementing a community-based social marketing program to increase recycling. Soc. Mark. Q. 2009, 15, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Changing behavior with normative feedback interventions: A field experiment on curbside recycling. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 21, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Wu, S.W.; Wang, Y.L.; Wu, W.X.; Chen, Y.X. Source separation of household waste: A case study in China. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 2022–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotterill, S.; John, P.; Liu, H.; Nomura, H. Mobilizing citizen effort to enhance environmental outcomes: A randomized controlled trial of a door-to-door recycling campaign. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, W.J.; Day, R.; Olney, T.J. Commitment approach to motivating community recycling: New Zealand curbside trial. J. Consum. Aff. 1997, 31, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karout, N.; Altuwaijri, S. Impact of health education on community knowledge, attitudes and behaviour towards solid waste management in Al Ghobeiry, Beirut. EMHJ-East. Mediterr. Health J. 2012, 18, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyas, J.K.; Shaw, P.J.; Van-Vygt, M. Provision of feedback to promote householders’ use of a kerbside recycling scheme: A social dilemma perspective. J. Solid Waste Technol. Manag. 2004, 30, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Werff, E.; Vrieling, L.; Van Zuijlen, B.; Worrell, E. Waste minimization by households–A unique informational strategy in the Netherlands. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 144, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Cimmuto, A.; Mannocci, A.; Ribatti, D.; Boccia, A.; La Torre, G. Impact on knowledge and behaviour of the general population of two different methods of solid waste management: An explorative cross-sectional study. Waste Manag. Res. 2014, 32, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosono, T.; Aoyagi, K. Effectiveness of interventions to induce waste segregation by households: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Mozambique. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2018, 20, 1143–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, J.; Sadeghi, M.; Fadaei, E.; Mehdinejad, M. The effect of intervention through both face to face training and educational pamphlets on separation and recycling of solid waste in the Kalaleh City. Iran. J. Health Environ. 2015, 8, 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, X.; Nikolic, I.; Dijkhuizen, B.; van den Hoven, M.; Minderhoud, M.; Wäckerlin, N.; Wang, T.; Tao, D. Behaviour change in post-consumer recycling: Applying agent-based modelling in social experiment. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msengi, I.G. Development and evaluation of innovative recycling intervention program using the health belief model (HBM). Open J. Prev. Med. 2019, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flygansvær, B.; Samuelsen, A.G.; Støyle, R.V. The power of nudging: How adaptations in reverse logistics systems can improve end-consumer recycling behavior. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2021, 51, 958–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, S.; Nemati, R.; Natah, P.; Rajan, R.; Rane, S. Effectiveness of Information Booklet on Knowledge, Practices and Willingness Regarding Recycling of Solid Household Waste Management among Residents. Med. Leg. Update 2020, 20, 130–134. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhan, C. Out of sight, out of mind: Issues and obstacles to recycling in Ontario’s multi residential buildings. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 108, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werff, E.; Lee, C.-Y. Feedback to Minimize Household Waste a Field Experiment in The Netherlands. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, N.; Johnson, S.; James, R. Effect of Nurse-led Education on Knowledge of Housewives Regarding Household Waste Management. Nurs. J. India 2016, 107, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amanidaz, N.; Yaghmaeian, K.; Dehghani, M.H.; Mahvi, A.H.; Bakhshoodeh, R. Households’ behavior and social-environmental aspects of using bag dustbin for waste recovery in Tehran. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2019, 17, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widiyanto, A.F.; Suratman, S.; Alifah, N.; Murniati, T.; Pratiwi, O.C. Knowledge and practice in household waste management. Kesmas: J. Kesehat. Masy. Nas. (Natl. Public Health J.) 2019, 13, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, S.; Fataei, E.; Imani, A.A. Effects of source separation education on solid waste reduction in developing countries (a case study: Ardabil, Iran). J. Solid Waste Technol. Manag. 2019, 45, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.; Asadi, Z.S.; Rakhshani, T.; Mohammadi, M.J.; Azadi, N.A. The effect of an educational intervention based on the Integrated Behavior Model (IBM) on the waste separation: A community based study. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 8, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zand, A.D.; Heir, A.V.; Tabrizi, A.M. Investigation of knowledge, attitude, and practice of Tehranian women apropos of reducing, reusing, recycling, and recovery of urban solid waste. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MOOC. Solid Waste Management (MOOC). Open Learning Campus. Washington World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA. 2020. Available online: https://olc.worldbank.org/content/solid-waste-management-mooc (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Heidari, A.; Kolahi, M.; Behravesh, N.; Ghorbanyon, M.; Ehsanmansh, F.; Hashemolhosini, N.; Zanganeh, F. Youth and sustainable waste management: A SEM approach and extended theory of planned behavior. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2018, 20, 2041–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweneboah-Koduah, E.Y.; Adams, M.; Nyarku, K.M. Using theory in social marketing to predict waste disposal behaviour among households in Ghana. J. Afr. Bus. 2020, 21, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighatjoo, S.; Tahmasebi, R.; Noroozi, A. Application of Community-Based Social Marketing (CBSM) to Increase Recycling Behavior (RB) in Primary Schools. Soc. Mark. Q. 2020, 26, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.T.; Ross, S.R.; Irwin, R.L. Utilizing community-based social marketing in a recycling intervention with tailgaters. J. Intercoll. Sport 2015, 8, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeabai, N.; Areeprasert, C.; Siripaiboon, C.; Khaobang, C.; Congsomjit, D.; Takahashi, F. The effects of compost bin design on design preference, waste collection performance, and waste segregation behaviors for public participation. Waste Manag. 2022, 143, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-Jurado, M.Á.; Gil-Madrona, P.; Ortega-Dato, J.F.; Zamorano-García, D. Effects of an educational glass recycling program against environmental pollution in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, F.; Liu, Y. Pro-environmental behavior in an aging world: Evidence from 31 countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.; Modi, A.; Paul, J. Pro-environmental behavior and socio-demographic factors in an emerging market. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 6, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Escario, J.-J. Heterogeneity in the association between environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behavior: A multilevel regression approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, C. The garbage gospel: Using the theory of planned behavior to explain the role of religious institutions in affecting pro-environmental behavior among ethnic minorities. J. Environ. Educ. 2018, 49, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Adams, M.; Walker, T.R. Are exports of recyclables from developed to developing countries waste pollution transfer or part of the global circular economy? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Levi, N.; Araya-Córdova, P.J.; Dávila, S.; Vásquez, Ó.C. Promoting adoption of recycling by municipalities in developing countries: Increasing or redistributing existing resources? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ren, C.; Dong, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z. Determinants shaping willingness towards on-line recycling behaviour: An empirical study of household e-waste recycling in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 143, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaikova, A.; Deviatkin, I.; Havukainen, J.; Horttanainen, M.; Astrup, T.F.; Saunila, M.; Happonen, A. Factors influencing household waste separation behavior: Cases of Russia and Finland. Recycling 2022, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).