Towards the Human Circular Tourism: Recommendations, Actions, and Multidimensional Indicators for the Tourist Category

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Circular Economy and Tourism Sector

2.1. The Concept of the Circular Tourism: The State of the Art

2.2. The Evalation Process in the Implementation of the Circular Tourism

3. The UNWTO Approach: A Call for Action for Tourism’s COVID-19 Mitigation and Recovery

Tourism for SDGs Platform

- “Managing the Crisis and Mitigating the Impact” in which the recommendations related to the economic and social impacts of COVID-19 are mainly highlighted, specifically those linked to employment and the most vulnerable people.

- “Providing Stimulus and Accelerating Recovery” which includes recommendations that emphasize the importance of providing financial stimulus to boost marketing and consumer confidence and also the need to place tourism at the center of national recovery policies and action plans;

- “Preparing for Tomorrow” in which the recommendations emphasize the role of the tourism sector in the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals through the implementation of the circular economy model.

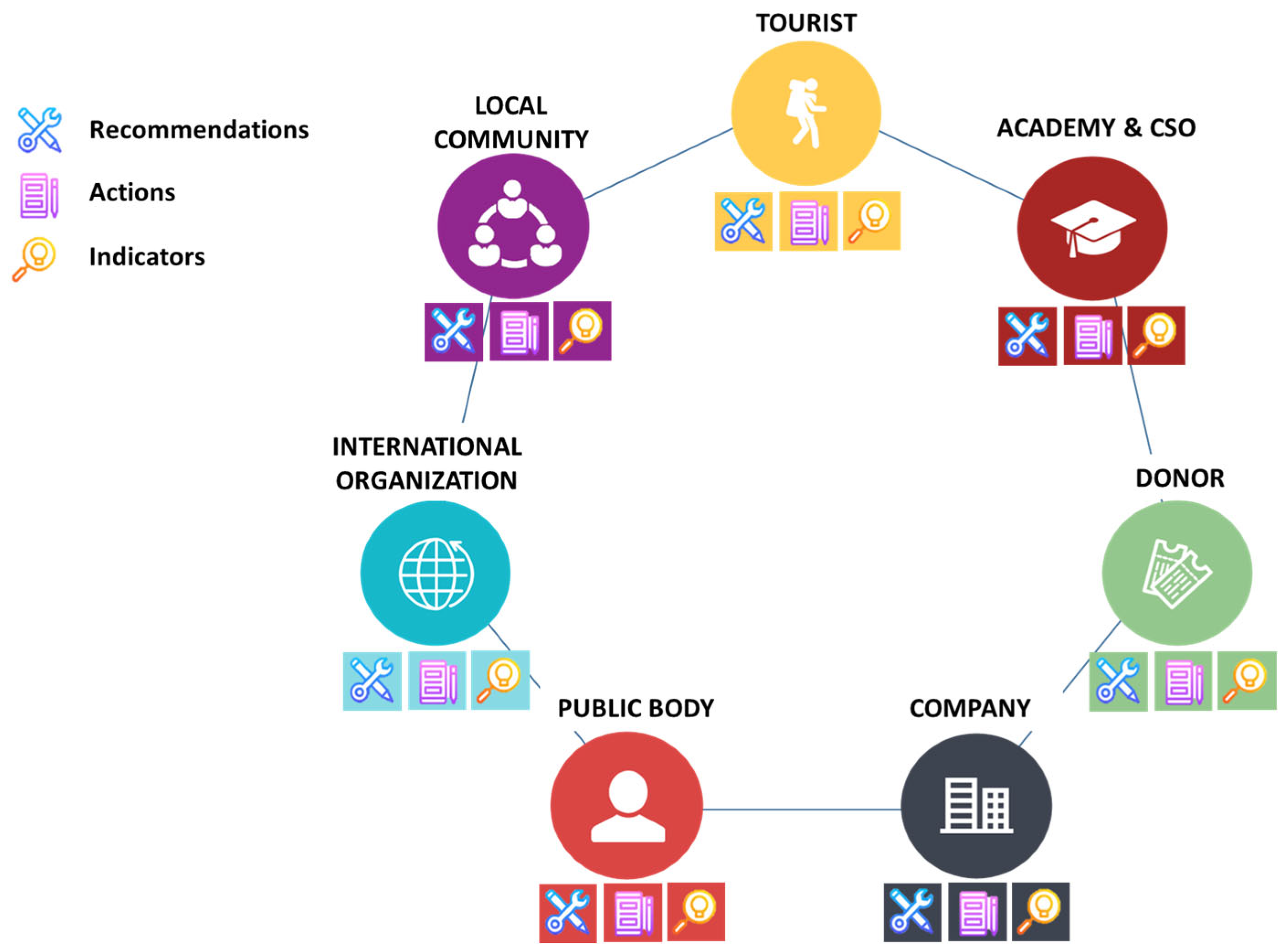

4. The Tourists’ Category: How to Operationalize the Human Circular Tourism

4.1. Recommendations and Actions for Implementing Human Circular Tourism

4.2. Multidimensional Indicators for Assessing the Circular Actions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN Habitat. Envisaging the Future of Cities; World Cities Report; UN Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Division for Sustainable Development Goals: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. New Urban Agenda. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development, Quito, Ecuador, 17–20 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nocca, F. Climate Change and Health Impacts in Urban Areas: Towards Hybrid Evaluation Tools for New Governance. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Impact Assessment of the COVID-19 Outbreak on International Tourism. UGC Care Gr. I List. J. 2020, 10, 148–159. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. Technical Meeting on COVID-19 and Sustainable Recovery in the Tourism Sector; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sunlu, U. Environmental Impacts of Tourism. In Local Resources and Global Trades: Environments and Agriculture in the Mediterranean Region; Camarda, D., Grassini, L., Eds.; CIHEAM: Bari, Italy, 2003; Volume 57, pp. 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Manniche, J.; Larsen, K.T.; Broegaard, R.B.; Holland, E. Destination: A Circular Tourism Economy. A Handbook for Transitioning toward a Circular Economy within the Tourism and Hospitality Sectors in the South Baltic Region; Centre for Regional & Tourism Research: Bornholm, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Circular City Funding Guide What Are the Benefits of a Circular Tourism Sector? Available online: https://www.circularcityfundingguide.eu/circular-sector/tourism/ (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Bosone, M.; Nocca, F. Human Circular Tourism as the Tourism of Tomorrow: The Role of Travellers in Achieving a More Sustainable and Circular Tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circular Economy in Travel and Tourism: A Conceptual Framework for a Sustainable, Resilient and Future Proof Industry Transition. CE360 Alliance 2020. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/covid-19-oneplanet-responsible-recovery-initiatives/circular-economy-in-travel-and-tourism-a-conceptual-framework-for-a-sustainable-resilient-and-future-proof-industry-transition (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- CenTour Project. CEnTOUR—Circular Economy in Tourism. Available online: https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/knowledge-centre/resources/centour-circular-economy-tourism (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. What Is a Circular Economy? Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/topics/circular-economy-introduction/overview (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- European Commission. The European Tourism Indicator System: ETIS Toolkit for Sustainable Destination Management; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chertow, M.R. Industrial Symbiosis: Literature and Taxonomy. Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 2000, 25, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L. Implementing the Circular Economy: The Role of Cultural Heritage as the Entry Point. Which Evaluation Approaches? BDC Boll. Del Cent. Calza Bini 2019, 19, 245–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L. Creative Cities: The Challenge of “Humanization” in the City Development. BDC Boll. Del Cent. Calza Bini 2013, 13, 9–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Growth within: A Circular Economy Vision for a Competitive Europe; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Isle of Wight, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lemille, A.; Circular Human. Flows Enhancing Humans as an Integral Part of Circular Economic Flows. Available online: https://alexlemille.medium.com/circular-human-flows-9106c8433bc8 (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Lemille, A. The Circular Economy 2.0 Ensuring That Circular Economy Is Designed for All; Medium: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The Human-Centred City: Opportunities for Citizens through Research and Innovation; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The Human-Centred City: Recommendations for Research and Innovation Actions; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Rethinking Tourism: From Crisis to Transformation; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, J.; Mitchell, P. Employment and the Circular Economy. Job Creation in a More Resource Efficient Britain; Green Alliance: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, P.; Lemille, A.; Desmond, P. Making the Circular Economy Work for Human Development. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 156, 104686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. COP24 Special Report: Health and Climate Change; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Belesova, K.; Boykoff, M.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Capstick, S.; et al. The 2019 Report of The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: Ensuring That the Health of a Child Born Today Is Not Defined by a Changing Climate. Lancet 2019, 394, 1836–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Belesova, K.; Bouley, T.; Boykoff, M.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Chambers, J.; et al. The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: From 25 Years of Inaction to a Global Transformation for Public Health. Lancet 2018, 391, 581–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Hurley, F.; Grobicki, A.; Keating, T.; Stoett, P.; Baker, E.; Guhl, A.; Davies, J.; Ekins, P. Communicating the Health of the Planet and Its Links to Human Health. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e204–e206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Beagley, J.; Belesova, K.; Boykoff, M.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; et al. The 2020 Report of The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: Responding to Converging Crises. Lancet 2021, 397, 129–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, V.; Sahakian, M.; van Griethuysen, P.; Vuille, F. Coming Full Circle: Why Social and Institutional Dimensions Matter for the Circular Economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2004th ed.; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2005th ed.; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2008th ed.; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Methodological Work on Measuring the Sustainable Development of Tourism-Part 2: Manual on Sustainable Development Indicators of Tourism; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- The Global Sustainable Tourism Council. GSTC Destination Criteria Version 2.0 with Performance Indicators and SDGs; The Global Sustainable Tourism Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Travel & Tourism Council. Economic Impact Reports; World Travel & Tourism Council: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stankov, U.; Gretzel, U. Tourism 4.0 Technologies and Tourist Experiences: A Human-Centered Design Perspective. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. UNWTO World Tourism Barometer and Statistical Annex, September 2021; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2021; Volume 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. UNWTO World Tourism Barometer and Statistical Annex, January 2022; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2022; Volume 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Secretary-General Zurab Pololikashvili Secretary-General’s Policy Brief on Tourism and COVID-19; United Nations World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- One Planet Sustainable Tourism Programme. Glasgow Declaration: A Commitment to a Decade of Climate Action; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A. The Unavoidable Disruption of the Circular Economy in Tourism. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y. Research on the development of tourism circular economy in Henan province. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Cluster Development and Management, Changzhou, China, 20 November 2008; pp. 550–554. [Google Scholar]

- Niñerola, A.; Sánchez-Rebull, M.-V.; Hernández-Lara, A.-B. Tourism Research on Sustainability: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Hu, X.X. A Path Study on the Tourism Circular Economic Development of Shandong Province. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 962–965, 2234–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.; Florido, C.; Jacob, M. Circular Economy Contributions to the Tourism Sector: A Critical Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P. Low Carbon Tourism and Strategies of Carbon Emission Reduction. In Proceedings of the 2015 2nd International Symposium on Engineering Technology, Education and Management (ISETEM 2015), Guangzhou, China, 24–25 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nocca, F. From Linear to Circular Tourism. Aestimum 2017, 70, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, F.; Bærenholdt, J.O. Tourist Practices in the Circular Economy. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, C. Exploring Circularity: A Review to Assess the Opportunities and Challenges to Close Loop in Nepali Tourism Industry. J. Tour. Adventure 2020, 3, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamfilie, R.; Firoiu, D.; Croitoru, A.G.; Ioan Ionescu, G.H. Circular Economy—A New Direction for the Sustainability of the Hotel Industry in Romania? Amfiteatru Econ. 2018, 20, 388–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INCIRCLE Project. Measuring Tourism as a Sustainable and Circular Economic Sector. The INCIRCLE Model Deliverable 3.3.1 INCIRCLE Set of Circular Tourism Indicators; INCIRCLE Project: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- GRO Together Let’s Gro Together. Available online: https://gro-together.com/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Katica Tanya Élményközpont Ladybird Farm Leisure Center. Available online: https://www.vortex-intl.com/projects/ladybird-farm-leisure-centre/ (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Van Rheede, A.; Circular Economy as an Accelerator for Sustainable Experiences in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry. Academia. Edu. 2012. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/17064315/Circular_Economy_as_an_Accelerator_for_Sustainable_Experiences_in_the_Hospitality_and_Tourism_Industry (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- HM Hotel Centrale SRL Central Hotel Moena. Available online: https://www.centralhotel.it/ (accessed on 24 December 2022).

- Sextantio. Le Grotte Delle Civita. Available online: https://www.sextantio.it/legrottedellacivita/matera/?adblast=7104388388&vbadw=7104388388&gclid=CjwKCAiAhqCdBhB0EiwAH8M_GkltPTN3OUZbhWcQ0eW3OzbUtoCcpu6fUYAm2n-SFEGMpF-77l62OBoCt90QAvD_BwE (accessed on 24 December 2022).

- VisitNaples.Eu. Available online: https://www.visitnaples.eu/ (accessed on 24 December 2022).

- CircE Interreg Europe Project. Slovenia Action Plan. Association of Municipalities and Towns of Slovenia; CircE Interreg Europe Project: Maribor, Slovenia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WTO. Indicators of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destinations A Guidebook (English Version); World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2004; ISBN 9789284407262. [Google Scholar]

- Nocca, F.; Fusco Girard, L. Towards an Integrated Evaluation Approach for Cultural Urban Landscape Conservation/Regeneration. Region 2018, 5, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovidou, E.; Velis, C.A.; Purnell, P.; Zwirner, O.; Brown, A.; Hahladakis, J.; Millward-Hopkins, J.; Williams, P.T. Metrics for optimising the multi-dimensional value of resources recovered from waste in a circular economy: A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 910–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, P.; Capocchi, A.; Foroni, I.; Zenga, M. An Assessment of the Implementation of the European Tourism Indicator System for Sustainable Destinations in Italy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nijkamp, P. Le Valutazioni per Lo Sviluppo Sostenibile Della Città e Del Territorio; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Corona, B.; Shen, L.; Reike, D.; Carreón, J.R.; Worrell, E. Towards sustainable development through the circular economy—A review and critical assessment on current circularity metrics. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 151, 104498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzberg, J.; Lonca, G.; Hanes, R.J.; Eberle, A.L.; Carpenter, A.; Heath, G.A. Do We Need a New Sustainability Assessment Method for the Circular Economy? A Critical Literature Review. Front. Sustain. 2021, 1, 620047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, R. Measuring Tourism: Methods, Indicators, and Needs. In The Future of Tourism: Innovation and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baggio, R. Symptoms of Complexity in a Tourism System. Tour. Anal. 2008, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.S.C.; Sirakaya, E. Sustainability Indicators for Managing Community Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1274–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmelash, A.G.; Kumar, S. The Structural Relationship between Tourist Satisfaction and Sustainable Heritage Tourism Development in Tigrai, Ethiopia. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; McKercher, B.; Suntikul, W. Identifying Core Indicators of Sustainable Tourism: A Path Forward? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; Palomeque, F.L. Measuring Sustainable Tourism at the Municipal Level. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.A. Social Influence, Empathy, and Prosocial Behavior in Cross-Cultural Perspective. In The Practice of Social influence in Multiple Cultures; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2000; ISBN 9781410601810. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; Cumberland, J.H.; Daly, H.; Goodland, R.; Norgaard, R.B.; Kubiszewski, I.; Franco, C. An Introduction to Ecological Economics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boulding, K.E. The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth. In Environmental Quality in A Growing Economy: Essays from the Sixth RFF Forum; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F. Il Tao Della Fisica; Adelphi Edizioni: Milan, Italy, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Serageldin, I. Cultural Heritage as Public Good: Economic Analysis Applied Ot Historic Cities. In Global Public Goods. International Cooperation in the 21st Century; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Rationality and Social Choiche. In Rationality and Freedom; Belknap Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R. Ecological Economics. The Science and Management of Sustainability; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, E.F. Piccolo è Bello. Uno Studio Di Economia Come Se La Gente Contasse Qualcosa; Ugo Mursia Editore: Milano, Italy, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L. The Evolutionary Circular and Human Centered City: Towards an Ecological and Humanistic “Re-Generation” of the Current City Governance. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2021, 40, 753–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Better Life Index. Available online: https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org (accessed on 24 December 2022).

- Eurostat Quality of Life. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/infographs/qol/index_en.html (accessed on 24 December 2022).

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Global Trends in Length of Stay: Implications for Destination Management and Climate Change. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 2087–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styles, D.; Schönberger, H.; Martos, J.L.G. Best Environmental Management Practice in the Tourism Sector; European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cianga, N. The Impact of Tourism Activities. A Point of View. Risks Catastrophes J. 2017, 20, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemma, A.F. Tourism Impacts: Evidence of Impacts on Employment, Gender, Income; DFID Economics and Private Sector Professional Evidence and Applied Knowledge Services (EPS-PEAKS). 2014. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a089f2ed915d622c000495/Tourism_Impacts_employment_gender_income_A_Lemma.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- Pratt, L. Tourism-Investing in Energy and Resource Efficiency; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Halleux, V. Sustainable Tourism: The Environmental Dimension; European Parliament Research Service: Strasbourg, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Asmelash, A.G.; Kumar, S. Assessing Progress of Tourism Sustainability: Developing and Validating Sustainability Indicators. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhao, H.; Guo, S. Evaluating the Comprehensive Benefit of Eco-Industrial Parks by Employing Multi-Criteria Decision Making Approach for Circular Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2262–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; Saarinen, J. Using Indicators to Assess Sustainable Tourism Development: A Review. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Global Sustainable Tourism Council. GSTC Industry Criteria Version 3 with Performance Indicators for Hotels and Accommodations and Corresponding SDGs; The Global Sustainable Tourism Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Abarca Garrido, C.; Rodríguez Quintero, R.; Wolf, O.; Bojczuk, K.; Castella, T.; Tewson, J. Revision of European Ecolabel Criteria for Tourist Accommodation and Camp Site Services. Final Criteria Proposal; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hanza, R. Contributions Regarding the Research of the Sustainable Development in Agro-Tourism from a Circular Economy Perspective; Universitatea “Lucian Blaga” din Sibiu: Sibiu, Romania, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The Global Sustainable Tourism Council. GSTC Industry Criteria for Hotels & Tour Operators; The Global Sustainable Tourism Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Global Reporting Initiative. Tour Operators’ Sector Supplement; Global Reporting Initiative: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Global Reporting Initiative. Sustainability Topics for Sectors: What Do Stakeholders Want to Know? Research Development Series; Global Reporting Initiative: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Decision (EU) 2016/611 under Regulation 1221/2009 (EMAS); European Commission: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Interreg MED INCIRCLE Project Replication Toolkit. Available online: https://www.incircle-kp.eu/replication-toolkit/ (accessed on 24 December 2022).

- Interreg MED INCIRCLE Project Circular Tourism Self Assessment. Available online: https://www.incircle-kp.eu/self-assessment/ (accessed on 24 December 2022).

- UNWTO Tourism for SDGs (T4SDG) Platform. Available online: https://tourism4sdgs.org/the-platform/ (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Brundtland, G.H. World Summit on Sustainable Development. BMJ 2002, 325, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viard, J. Court Traité Sur Les Vacances, Les Voyages et l’hospitalité Des Lieux; Aube: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies, 1st ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1990; ISBN 978-0803981836. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Call for Action for Tourism’s COVID-19 Mitigation and Recovery; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Global Guidelines to Restart Tourism; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Clawson, M.; Knetsch, J.L. Economics of Outdoor Recreation; RFF Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781135989941. [Google Scholar]

- Flognfeldt, T., Jr. The Tourist Route System–Models of Travelling Patterns. Belgeo 2005, 1, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advance 360. The Five Stages of Travel; Advance 360: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pencarelli, T.; Splendiani, S.; Dini, M. Tourism Enterprises and Sustainable Tourism: Empiricalevidence from the Province of Pesaro Urbino. In Proceedings of the 14th Toulon-Verona Conference (ICQSS), Alicante, Spagna, 1–3 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Booking.com. Il Report Sui Viaggi Sostenibili Di booking.com per Il. 2022. Available online: https://news.booking.com/it/clima-comunita-e-scelte-bookingcom-rivela-le-tendenze-per-i-viaggi-sostenibili-nel-2022/ (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Naydenov, K. Circular Tourism as a Key for Eco-Innovations in Circular Economy Based on Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference Surveying Geology and Mining Ecology Management, SGEM, Albena, Bulgaria, 2–8 July 2018; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future (Report for the World Commission on Environment and Development, United Nations); United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Vecco, M. Genius Loci: The Evaluation of Places between Instrumental and Intrinsic Values. BDC. Boll. Del Cent. Calza Bini 2019, 19, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocca, F.; De Toro, P.; Voysekhovska, V. Circular Economy and Cultural Heritage Conservation: A Proposal for Integrating Level(s) Evaluation Tool. Aestimum 2021, 78, 105–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocca, F.; Angrisano, M. The Multidimensional Evaluation of Cultural Heritage Regeneration Projects: A Proposal for Integrating Level(s) Tool—The Case Study of Villa Vannucchi in San Giorgio a Cremano (Italy). Land 2022, 11, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecco, M. Genius Loci as a Meta-Concept. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 41, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravagnuolo, A.; Micheletti, S.; Bosone, M. A Participatory Approach for “Circular” Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage. Building a Heritage Community in Salerno, Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosone, M.; Ciampa, F. Human-Centred Indicators (HCI) to Regenerate Vulnerable Cultural Heritage and Landscape towards a Circular City: From the Bronx (NY) to Ercolano (IT). Sustainability 2021, 13, 5505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Recommendations | Actions | |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Dimension | ||

| 1 | To be a responsible tourist | A1.1 Give preference to staying in facilities that are or offer carbon-positive activities (adapted from UNWTO). |

| A1.2 Buy from companies that adopt sustainable practices and do not harm the environment (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| A1.3 Pay attention (and modify behaviors) according to the information provided by the monitoring sensors in accommodation structures or in transportation means. | ||

| 2 | To reduce waste | A2.1 Make separate waste collection. |

| A2.2 Reduce the utilization of not recyclable products. | ||

| A2.3 Stop printing booking confirmations and boarding passes, instead have digital copies of these documents (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| A2.4 Buy minimally packaged goods (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| A2.5 Support second-hand and gift economy (i.e., using sharing platform, donating to charity organization). | ||

| A2.6 Bring own bag for shopping (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| A2.7 Order or fill plates with the amount of food that can actually be eaten (for avoiding leftovers) (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| A2.8 “Recover” the food that has not been eaten (i.e., asking for a “doggy bag”, using apps for avoiding food waste) (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| 3 | To reduce emissions | A3.1 Buy km0 products. |

| A3.2 Prefer soft mobility. | ||

| A3.3 Prefer clean transport. | ||

| A3.4 Prefer public transport rather than individual transport (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| A3.5 Use cooling and heating systems in a wise way. | ||

| A3.6 Use sharing transport. | ||

| 4 | To reduce the consumption of non-renewable resources | A4.1 Prefer activities and services that use renewable resources (rainwater recovery systems, reuse of wastewater, etc.) (adapted from UNWTO). |

| A4.2 Use water system in a wise way (i.e., reduce water and energy consumption whenever possible, take shorter showers and air-dry hair whenever possible) (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| Economic Dimension | ||

| 5 | To support local economies | A5.1 Buy locally-made handcrafts and products, paying fair prices (adapted from UNWTO). |

| A5.2 Prefer the consumption of local food products. | ||

| A5.3 Sustain local enterprise and projects (i.e., through donations, active participation, and promotion of the enterprise activities). | ||

| Social Dimension | ||

| 6 | To contribute to cultural and knowledge exchange and integration (between tourists and local community) | A6.1 Learn to speak a few words in the local language. This can help you connect with the local community in a more significant way (adapted from UNWTO). |

| A6.2 Speak with local people. | ||

| A6.3 Speak with other tourists you meet along the way. | ||

| A6.4 Hire local guides with in-depth knowledge of the area (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| A6.5 Share initiatives or social projects considered interesting during the tourist experience and learn from them (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| A6.6 Propose and share (on social networks or on platforms such as the UNWTO one) innovative ideas that can reshape and benefit the tourism sector and make it more sustainable (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| A6.7 Share feedback about tourist destinations and tourist experience (word of mouth, giving feedback on tourist digital platforms). | ||

| 7 | To enhance own cultural experiences | A7.1 Take part in local cultural activities (also through cooperative and collaborative behaviors). |

| A7.2 Research information and learn about local culture, customs, traditions, and conditions before leaving and during the trip. It is a great way to build understanding of the local lifestyle and excitement for your adventure ahead (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| 8 | To respect authenticity and integrity of cultural and natural heritage and values of local communities | A8.1 Adopt respectful behaviors (respect values and traditions of the local community). |

| A8.2 Report any inappropriate or discriminatory behaviors that happened during tourist experience or online (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| A8.3 Adopt respectful behaviors for man-made and environmental resources (i.e., comply with local regulations regarding the enjoyment of environmental and cultural heritage, respect wildlife and their natural habitats) (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| 9 | To preserve health condition | A9.1 Use already existing resources on health for guidance (e.g., from the ILO, WHO, etc.) (adapted from UNWTO). |

| A9.2 Protecting oneself from diseases (vaccinate yourself, use anti-COVID mask) (adapted from UNWTO). | ||

| 10 | To be an aware tourist | A10.1 Use services supplied by e-tourism to customize the tourist experience and become an aware tourist. |

| A10.2 Improve the knowledge of the Global Code of Ethics for Tourism (from UNWTO). | ||

| Reference Action | Indicator | Unit of Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Dimension | ||

| A1.1 | I1 Amount of bookings in eco-friendly facilities. | %/year or N./year |

| A1.2 | I2 Amount of purchases in companies that adopt sustainable practices and do not harm the environment. | %/year or N./year |

| A1.3 | I3 Amount of tourists that declares to adapt their behaviors according to the information provided by the monitoring sensors. | %/year or N./year |

| A2.1 | I4 Percentage of separate collection on the total amount of waste produced in a tourist accommodation. | %/year |

| A2.2 | I5 Amount of tourists that declares to use recyclable products (glass, water, etc.). | %/year or N./year |

| A2.3 | I6 Amount of tourists presenting a printed booking confirmation at the reception desk. | %/year or N./year |

| A2.4 | I7 Amount of tourists that declare to buy minimally packaged goods. | %/year or N./year |

| A2.5 | I8 Expenditure in second-hand and gift products. | €/year |

| A2.6 | I9 Amount of tourists that declare to bring their own bag for shopping. | %/year or N./year |

| A2.7 | I10 Amount of tourists that order plates with the amount of food that they can actually eat. | %/year or N./year |

| A2.8 | I11.a Amount of doggy bags required in food facilities. | %/year or N./year |

| I11.b Amount of tourists that use apps for avoiding food waste. | %/year or N./year | |

| A3.1 | I12 Amount of tourists buying km0 products. | %/year or N./year |

| A3.2 | I13 Amount of tourists using soft mobility (bicycle). | %/year or N./year |

| A3.3 | I14 Amount of tourists using clean transport (electric vehicles). | %/year or N./year |

| A3.4 | I15 Amount of tourists using public transport. | %/year or N./year |

| A3.5 | I16 Amount of tourists declaring to pay attention to cooling and heating consumption. | %/year or N./year |

| A3.6 | I17 Amount of tourists using sharing transport. | %/year or N./year |

| A4.1 | I18 Amount of tourists choosing activities and services that use renewable resources. | %/year or N./year |

| A4.2 | I19 Amount of tourists declaring to pay attention to water system. | %/year or N./year |

| Economic Dimension | ||

| A5.1 | I20 Amount of tourists buying locally-made handcrafts and products paying fair price. | %/year or N./year |

| A5.2 | I21 Amount of tourists declaring to consume local food products. | %/year or N./year |

| A5.3 | I22.1 Amount of donations for supporting local tourism activities. | €/year |

| I22.2 Amount of tourists involved in activities of local enterprises. | N./year | |

| I22.3 Willingness To Pay (WTP) for contribution to cultural and natural heritage conservation. | €/tourist/year | |

| Social Dimension | ||

| A6.1 | I23 Amount of tourists declaring that want to learn to speak a few words in the local language (based on interviews). | %/year or N./year |

| A6.2 | I24 Amount of tourists declaring that are interested in speaking with local people during the tourist experience (based on interviews). | %/year or N./year |

| A6.3 | I25 Amount of tourists declaring that speak with other tourists they meet along the way (based on interviews). | %/year or N./year |

| A6.4 | I26 Amount of tourists who have hired local guides (on the total of tourists). | %/year or N./year |

| A6.5 | I27 Amount of tourists who share initiatives or social projects considered interesting during the travels. | %/year or N./year |

| A6.6 | I28 Amount of innovative ideas proposed that can reshape and benefit the tourism sector and make it more sustainable. | %/year or N./year |

| A6.7 | I29.1 Amount of tourists sharing feedback about tourist destinations and experience. | %/year or N./year |

| I29.2 Percentage of tourists satisfied with tourist initiatives. | %/year | |

| A7.1 | I30.1 Amount of tourists participating in local cultural activities. | %/year or N./year |

| I30.1 Percentage of tourists who feel well received by the host community. | %/year | |

| I30.3 Amount of tourists involved in cooperative initiatives (also in activities with the local community). | %/year or N./year | |

| A7.2 | I31 Amount of tourists researching information and learning about local culture, customs, traditions, and conditions before leaving and during the trip. | %/year or N./year |

| A8.1 | I32 Amount of tourists adopting respectful behaviors (deducted from questionnaires and interviews). | %/year or N./year |

| A8.2 | I33 Amount of reporting about inappropriate or discriminatory behaviors that happened during tourist experience or online. | %/year or N./year |

| A8.3 | I34 Amount of tourists adopting respectful behaviors for man-made and environmental resources (deducted from questionnaires and interviews). | %/year or N./year |

| A9.1 | I35 Amount of download of existing resources on health for guidance. | %/year or N./year |

| A9.2 | I36 Percentage of tourists adopting health-safety measures. | %/year |

| A10.1 | I37 Amount of users of services supplied by e-tourism. | %/year or N./year |

| A10.2 | I38 Amount of tourists knowing about the Global Code of Ethics for Tourism. | %/year or N./year |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nocca, F.; Bosone, M.; De Toro, P.; Fusco Girard, L. Towards the Human Circular Tourism: Recommendations, Actions, and Multidimensional Indicators for the Tourist Category. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031845

Nocca F, Bosone M, De Toro P, Fusco Girard L. Towards the Human Circular Tourism: Recommendations, Actions, and Multidimensional Indicators for the Tourist Category. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):1845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031845

Chicago/Turabian StyleNocca, Francesca, Martina Bosone, Pasquale De Toro, and Luigi Fusco Girard. 2023. "Towards the Human Circular Tourism: Recommendations, Actions, and Multidimensional Indicators for the Tourist Category" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 1845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031845

APA StyleNocca, F., Bosone, M., De Toro, P., & Fusco Girard, L. (2023). Towards the Human Circular Tourism: Recommendations, Actions, and Multidimensional Indicators for the Tourist Category. Sustainability, 15(3), 1845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031845