Abstract

Health and school achievement play a crucial role in the integration of migrant students. This study aims to conduct an umbrella review of the effectiveness of school-based strategies on the academic and health outcomes of migrant school-aged children and youth and to link these intervention typologies to the Health Promoting School (HPS) approach. The study was conducted according to the PRISMA statement. Twenty-one reviews were analyzed, and 18 strategies were identified and categorized according to the six components of the HPS whole-school approach: individual skills, the school physical environment, school social environment, school policies, health and social services, and community links. Strategies related to five of the six components were identified, demonstrating that the HPS approach is a fitting framework to address migrant students’ needs. Moreover, evidence about the effects on both health and learning was shown; however, the integration of these two areas should be further explored. Finally, significant conditions that enhance or hinder implementation are described. Multi-component interventions and stakeholder engagement improve intervention impacts, while the relevance of cultural adaptation needs to be clarified. These results contribute to understanding the complexity of the challenges faced by migrant students and of the effective school-based strategies to promote their health and learning.

1. Introduction

Migration processes are a central topic of modern societies, and migrating implies a wide range of variables that affect integration, inclusion and health. This is particularly true for children and youth with migrant backgrounds, as they are faced with physical health, socio-emotional and academic and language challenges [1]. Migrant children are a vulnerable population at risk of dropping out or receiving a poorer education. In the framework of UNESCO’s Education for Sustainable Development, reorienting education to reach children at risk of marginalization is crucial in order to transform society for sustainable development and to meet the learning needs of all youth and children. Therefore, improvements in the culture, resources, pedagogy and community support to provide sustained education and improve student outcomes should take into consideration migrant students’ populations, their health and their academic successes [2].

1.1. Migrant Students’ Health and Learning

At the international level, no universally accepted definition for “migrant” exists. According to the United Nations’ International Organization for Migration (IOM) [3], migrant is an umbrella term that includes a number of well-defined legal categories of people and refers to any person who moves away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, regardless of the person’s legal status; whether the movement is involuntary or voluntary; or what the causes for that movement are. Even if within the literature on the topic a variety of different terms is used, for the purposes of this review, we decided to opt for this definition to include all categories of migrant students, avoiding distinctions among specific groups such as displaced children, asylum seekers, or refugees. The needs and characteristics of this population of students must be taken into consideration both in terms of health and learning. To allow for appropriate responses to migrant youth’s needs, it is important to be aware of the negative consequences, but also of the resources, that being a migrant student implies. The literature highlights that migrant students are exposed to several criticalities that determine vulnerabilities both in terms of their health and academic achievements. Moreover, social determinants of health have an impact on their emotional and physical well-being. For instance, they are often educated in under-resourced contexts, experience resettlement traumas and can be surrounded by hostile environments [4].

As a result, health equity is one of the major issues related with immigrant youth [5], and migrant students in most countries tend to have lower education outcomes than their native peers. Markedly, obstacles that hinder migrant students’ school results go beyond the linguistic proficiency gap [6,7,8], and their academic achievements continue to lag behind those of non-migrant children.

1.2. School and Migrant Students

Schools are tasked to respond to the multitude of physical health, mental health and academic issues specific to child migrants, as well as foster strengths in order to encourage positive educational outcomes. However, the literature on school-based strategies targeting migrant students is still limited [4,9]; therefore, it is crucial for researchers to explore the efficacy of school-based interventions. The school system is especially well-positioned to address the topic of migrant students’ health. It is usually the first institutional and social space in which students engage in cultural adaptation and the main contact place between migrant and native students. This makes the school the ideal place for programs that aim at promoting integration and inclusion [10]. Access to education and ensuring academic achievement are considered among the most important indicators for migrant children and adolescents’ adaptation [11]. Students who are well-integrated into the education system of the host country, both academically and socially, are more likely to reach their potential and be in good health conditions [10]. Consistently, research has also demonstrated that migrant students with a low academic performance show negative self-esteem, stress and insecurity [12,13].

Studies have shown that school- and community-based mental health programs/interventions can be effective in addressing psychosocial challenges and improving the mental health outcomes of migrant children and youth [9,14,15,16]. However, despite the numerous school programs that have been developed to prevent socio-emotional and behavioral problems and to foster migrant students’ health, education and adaptation, little is known about the types of activity that may work best and proper evaluations are needed [17].

1.3. Health Promoting School Approach

A widely recognized approach to promote students’ health and well-being is the Health Promoting School (HPS) model. The HPS approach acknowledges that learning and health are closely linked, while it aims to promote individual and organizational change and it recognizes that all school aspects can impact students’ health and well-being [18,19]. HPS is based on a whole-school approach and identifies six components that clarify how to act at the individual, organizational, and contextual levels to promote students’ health [19,20,21]: individual health skills and action competencies, the school’s physical environment, the school’s social environment, healthy school policies, health services collaboration and community links. HPS implementation is sustained by evidence-based actions to strengthen each of the six components [22]. The “individual health skills and action competencies” component includes the knowledge and skills which enable pupils to take actions related to health, well-being and educational attainment (e.g., health literacy or life skills). These skills and action competencies can be promoted through the curriculum or specific activities in the school’s everyday life. The “school physical environment” component includes the buildings, grounds and school surroundings. For example, strategies that aim to enhance the physical environment might be designed to make the school grounds more appealing for recreation or physical activity. The “school social environment” component is related to the quality of the relationships among and between school community members, which means strengthening and enhancing the relationships between the students themselves and between students and school staff. The “healthy school policies” are clearly defined documents or accepted practices designed to promote students’ well-being and health. For example, these policies may regulate which food can be served at school or describe how to prevent or address school bullying. With “health services”, the whole-school approach refers to the local and regional school-based or school-linked services that are responsible for the students’ health care and health promotion by providing specific services. This includes specific groups such as children with special needs or students with a migrant background. The services can encompass social services as well. Finally, the “community links” component includes the collaboration between the school and the pupils’ families and the school and key groups/individuals in the surrounding community.

The HPS model has been conceptualized to be implemented in different contexts, and its flexibility and multidimensionality allow it to address new and emerging issues [23,24]. It has been proven that such a model can also be effective in terms of equity and inequalities reduction [25]. It can be successfully implemented to improve health and academic outcomes in children and adolescents from low socio-economic backgrounds or from vulnerable groups. This approach is in line with an appropriate response to immigrant youth’s needs, which cannot be fully understood and addressed at the individual level only [11]. More precisely, to facilitate equal opportunities and outcomes for migrant students, it is important to comprehensively understand and address the interaction of individual and structural factors [4]. A greater consideration of the social environment is required within prevention and treatment programs and policies [17].

Although the potential of this approach is recognized, there is a lack of empirical knowledge on the impact of the HPS approach on immigrant school populations [5]. In light of this, there is a need for further research on how the Health Promoting School model can impact and be adapted to benefit immigrant students and their families effectively.

1.4. Aims of the Study

Given the above considerations, this study aims to conduct an umbrella review to examine the effectiveness of school-based strategies aimed at promoting migrant students’ health and academic outcomes and to link these intervention typologies to the six components of the Health Promoting School model: individual skills, school physical environment, school social environment, school policies, health and social services, and community links.

Specifically, we want to (1) synthesize the evidence of effectiveness of these strategies, (2) understand on which outcomes related to migrant students they have an impact, (3) identify key elements of these intervention typologies and compare them with the Health Promoting Schools model and its whole-school approach components, and (4) explore the effective conditions of implementation identified by the literature.

2. Materials and Methods

The main aim of umbrella reviews is compiling evidence from multiple reviews into one usable and accessible document. This kind of review focuses on broad themes or issues for which many competing interventions exist and have been evaluated by the literature; it highlights the available reviews addressing these interventions and their findings. The final scope of an umbrella review is to summarize the available knowledge and evidence, point out research gaps and suggest recommendations for practice and future research [26].

2.1. Search Strategy

This umbrella review includes reviews and meta-analyses on school-based interventions targeting migrant students. We conducted a comprehensive search of the literature using the following 4 online databases: PsychInfo, Scopus, Pubmed and ERIC. We searched for peer-reviewed review publications from 2005 to 2021 using the following keywords: ((school*) OR (education*) OR (student*)) AND ((intervention*) OR (program*) OR (initiative*)) AND ((refugee*) OR (asylum-seek*) OR (asylum seek*) OR (migran*) OR (migrat*) OR (immigra*) OR (displac*) OR (ethnic minorit*) OR (racial minorit*) OR (unaccompanied)) AND ((review) OR (meta analy*) OR (meta-analy*) OR (metaanaly*)). The search was set to identify studies in which these terms were used in the publications’ titles or abstracts. The search terms and strategy were adapted to match the specific structure of each database used. We identified additional literature by searching manually and based on the reference lists of selected papers. These additional reviews were not focused on schools exclusively, but they included school-based interventions in their analysis.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The search strategy targeted the period from 2005 to 2021 to focus on the last 15 years of research. The characteristics of migration are constantly changing. We therefore wanted to look at a significant but shortened historical period. The publications had to be peer-reviewed and written in English, Italian or Spanish. More specific inclusion and exclusion criteria have been defined according to the review aim, following the PICO Model:

- Population: only reviews regarding children or youth identified as migrants, immigrants, asylum seekers, refugees or displaced individuals were included. We excluded papers exclusively focused on adults; if reviews also considered studies targeting adults, only the separate results for children and adolescents were included. We did not include papers concerning interventions targeted exclusively to the general population of youths without a focus on migrant backgrounds. Papers whose target population consisted of ethnic or racial minorities who were not from migrant backgrounds were also excluded.

- Intervention: only reviews or meta-analysis that tested or evaluated interventions carried out in school settings (from kindergarten to high school completion) were included. When a publication included studies carried out in multiple settings, the results and outcomes had to be reported separately for the school setting. We excluded conceptual, descriptive, or non-evaluative papers. We also excluded papers that focused on factors affecting migrants’ health or integration policies but did not include interventions.

- Outcomes: changes in migrant students’ physical and mental health or socio-emotional well-being were included. Academic and school outcomes were also considered.

- Comparison: the articles had to be defined as a review or meta-analysis. Three mandatory criteria of the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) had to be met: the definition of a review question, the inclusion of a search strategy, and the presence of some data synthesis [27,28]. Reviews that considered randomized and nonrandomized trials and qualitative studies were included to identify the effective conditions of implementation better.

In line with previous studies [29], we did not limit the search by geographic location, to include migrant students experience in all of the potential receiving countries.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

During the first selection step, the titles and abstracts of potentially relevant publications that were identified were reviewed for eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. When in doubt, they were included to be screened in the second stage of a full-text analysis. For the second step, full copies of all the papers deemed eligible by one of the reviewers were retrieved for closer examination. The reasons for the non-inclusion of the studies were noted. Both stages of the selection were performed independently by two reviewers (VV and CM). In the case of disagreement, the articles and their criteria compliance were discussed among the reviewers; the decision to include the article was based on the consensus reached.

The studies that met all the inclusion criteria were subsequently coded for data extraction. The authors reviewed and approved the final coded matrix. The following data were extracted based on the reviews’ information: review details, intervention, search strategy, inclusion/exclusion criteria, methodology, number of databases searched, number of studies in the review, quality and risk bias assessment, included studies designs, classifications, countries analyzed, the main objective, school level of reviewed interventions’ samples, results obtained, outcomes considered, interventions’ components, the recommendations and the limits. Data were extracted and the narrative synthetized by one author and discussed and revised by another author. A quality assessment procedure was not used in this umbrella review, as most studies would have been rated as having a weak quality and eliminated. Indeed, although the reviews followed rigorous procedures, much methodological information was missing in the reviews selected, probably due to the characteristics of the journals and different disciplinary backgrounds.

Once the data extraction was performed, an initial stage of analysis was carried out to identify all the strategies/intervention typologies aimed at the migrant students’ health and academic achievements explored or described by the reviews. In total, 21 strategies were identified and briefly defined. According to their main aims, each strategy was categorized into the six components of the whole-school approach defined by the SHE—Schools for Health in Europe Network. This categorization was also performed independently by two reviewers (VV and CM) and any disagreements were discussed until a consensus was reached. We included both practices specifically thought for migrant youth and practices targeting all the students in the school when the outcomes for migrant students could be inferred.

3. Results

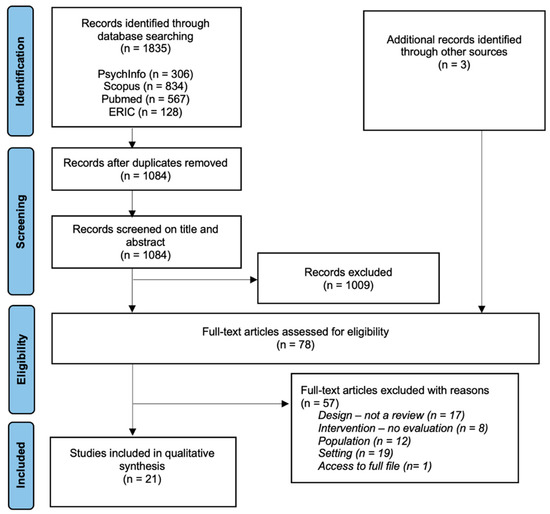

The database search yielded 1835 potentially relevant results. We removed 751 duplicates, leaving 1084 records for the screening phase. Through the first screening, we excluded 1009 articles that were clearly irrelevant to the topic or did not meet the inclusion criteria. Seventy-five records were included in the second phase of the selection. Through the more in-depth full text analysis, we excluded an additional 57 articles. Results were excluded mostly because (a) they could not be considered reviews; (b) they did not involve migrant youths as a target group or focused exclusively on adults or (c) they focused on very specific sub-groups; (d) they were not based on the evaluation of health promotion or educational interventions; and (e) they did not consider the school setting or did not report results separately for the school setting. In one case, full text could not be retrieved.

After the two selection steps, 18 reviews were identified for final inclusion. The manual searching resulted in another three reviews not identified by the original search strategy. These additional reviews were not focused on schools exclusively but they included school-based interventions in their analysis. The total number of included peer-reviewed studies was 21.

According to the flow diagram of the PRISMA declaration, Figure 1 is presented showing the flow of information followed in this study for the search and selection of articles.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of studies.

The quality of the reviews diverged greatly, and so did the level of analysis. In particular, some reviews provided a detailed explanation of the primary studies included, while others did not and only mentioned some examples of interventions or programs. Some reviews were more focused on the effects’ significance; others better considered the conditions of implementation or factors influencing migrants’ health and well-being. These differences are partially explained by the fact that the objectives pursued by the reviews differed considerably from one another.

After the data extraction and analysis, 18 strategies were identified in total. Some strategies were considered by several reviews, while others by just one or two. The strategies could be either specifically designed for migrant students or addressed to the entire student population; even when the strategies were directed to everybody, regardless of the local or migrant background, specific impacts on migrant sub-groups were usually described separately.

A narrative synthesis of the empirical research is presented below for each HPS approach component. Table 1 summarizes the findings and gives an overall vision of the results, reporting the number of reviews that took each strategy into account and the impacts on health and academic outcomes.

Table 1.

Summary of findings–strategies.

3.1. Individual Skills

In this section, we considered strategies assessed by the literature in which migrant students’ health, well-being and school outcomes were addressed from a perspective that focused on individual competences. It is important to clarify that some teachers’ training or parents’ engagement activities also focused on the individual level; however, since the target was not the student, the strategies involving teachers and parents were included in the respective categories. Table 2 summarizes the findings about the strategies categorized in the “individual skills” component.

Table 2.

Individual skills strategies.

3.1.1. Creative and Expressive Techniques

Creative and expressive techniques were undoubtedly the most frequently mentioned strategy, as they were brought up in 13 out of 21 reviews included in our research. They were designed to develop students’ well-being and inclusion; therefore, they belonged to the “individual skills” component. However, they also represented a bridge with the social and community components because they often entailed a shared participation in activities and relating to others. Following is a list of the main typologies of creative and expressive techniques or non-specialized therapies [29,37]: drama-based activities; storytelling and literary approaches (e.g., writing, sand-play, poetry, etc.); play-based creative activities; visual art (e.g., drawing and photography); performative (e.g., dancing and singing); audiovisual and multimedia; arts and music therapy; and multi-method forms. As they were designed to provide individuals with outlets to express feelings and process emotions, they all had in common the aim to give students the opportunity to share stories, process experiences, and to support the construction of meaning and identity and the transcultural exchange [29,36]. Additional purposes of these creative techniques included processing traumas, developing social-emotional skills, and, by extension, reducing impairment and improving school behavior or academic performance. The intensity of these interventions ranged from a few hours to multiple sessions over the entire school year, and the magnitude and scope varied across the studies. Such interventions can be carried out by trained art therapists, classroom teachers or a combination of the two assisting each other. Moreover, expressive techniques can be tailored to a group’s needs, for example, by changing the subjects of drawings or choosing a given music style [30]. Therefore, they can be adapted to specifically address migration topics; for instance, sharing musical cultures or choosing painting topics related to children’s pre-migration history [37].

Overall, all the reviews reported some degree of improvement in students’ outcomes, even if the effectiveness may have varied from one study to another. In general, expressive techniques are beneficial to all youth, especially when this strategy is implemented to be used with students who have been exposed to traumatic events [33]. Only two reviews partially disagreed with this: Sullivan and Simonson [30] reported less consistent results, and Bal and Perzigian [4] found a decrease in emotional and behavioral symptoms but no significant effects on self-esteem. Effectiveness has been assessed for various categories of outcomes since this strategy can impact many levels. More specifically, the findings have shown significant reductions in the symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD, hyperactivity and functional impairment [9,31,32,35]. Positive results have also been shown for general well-being, emotional adjustment, and relational problems [9]. Creative expression also helps with self-esteem, behavioral problems, conflict resolution and problem solving, constructing identity, dealing with loss, connecting with others, increasing a sense of belonging and happiness, enhancing the classroom climate while addressing acculturation issues and bridging the gap between home and school [17,29,37].

School and academic outcomes are less central for this strategy; however, some promising findings were mentioned by some reviews that found evidence of increases in math achievement [4], general improvements in school performance and reduced impairment [17,29] and improvements in language and culture learning [32].

3.1.2. Social and Emotional Skills Training

Social and emotional skills training was a widely analyzed strategy examined by seven of the included reviews. It operates on the students’ individual level to enhance their personal and social competences and abilities; yet, it is often linked to the school social environment and the community components, as it can engage teachers to deliver activities or impel parent and family sessions to complement the interventions with children. The social and emotional skills training interventions were usually carried out in group settings (either with the classroom integrated into the school curriculum or smaller groups) and delivered through a defined number of sessions by teachers or with program staff support [36]. Additionally, children were engaged in activities related to several topics. In some cases, they covered universal health and socio-emotional topics (such as emotion regulation skills, self-esteem, relationships, problem solving, and critical thinking); in others, the topics were more specifically related to migration issues (e.g., discrimination, social exclusion, etc.). Different programs and interventions to promote social and emotional skills were described in at least seven of the included reviews. The results appeared to be mixed and variable, reasonably not because of considerable variations in their effectiveness but because of the different program characteristics and the large number of outcomes measured. Concerning school outcomes, the reviews considered reported marginally significant changes in academic competence [4], but the effects were lower than those obtained through academic programs [40]. On the contrary, there was a positive impact on reducing school stress and increased attention levels [33] and the ability to work with peers was improved [31]. The findings related to health and psychosocial outcomes were also mixed. Beelman et al. [40] described small effect sizes within the socioemotional domain, while Bal and Perzigian [4] reported increased social competence based on teachers’ evaluations but not on student-rated scores, decreased internalizing behaviors, and no change in externalizing behaviors. Conversely, Del Pino-Brunet et al. [31] reported a significant impact on motivation, integration, happiness and aggressiveness, and Hettich et al. [32] highlighted lower anxiety and depression scores and improvements in dealing with stressful situations. Changes in health behaviors (such as hygiene) and a reduction in some behavioral problems were also observed, along with increased health care access. The effects on long term health and well-being were inconclusive and often not assessed [33,39].

The most effective social and emotional skills interventions for migrant students were those that focused on self-efficacy by teaching them coping skills and on the creation of the group as a safe space, those that emphasized family support, relationships and connectedness, that gave importance to cultural aspects and focused on adjustment difficulties and current life issues attributable to the post migration environment [32].

3.1.3. Academic Training, Cognition and Learning

This typology of interventions mainly referred to additional reinforcement lessons specifically addressed to migrant children and adolescents or training in cognitive learning strategies using bilingual lessons or specific learning software. In some cases, these interventions were aimed at helping immigrant students transition into inclusive classrooms by improving their mathematics and reading comprehension [4]. Two reviews presented this strategy, showing relatively high impacts [40], mainly regarding students’ cognitive functioning, reading comprehension and math ability [4]. Besides academic outcomes, no specific impacts were reported about health outcomes.

These interventions were often used in wider language and cognitive programs. When combined with other language and learning strategies, they showed higher and more generalized effects on both cognitive/academic and language/communication outcomes. Both the cognitive and language promotion intervention studies normally assessed predominantly proximal outcomes, such as language abilities and communication skills or cognitive and academic performance. Due to this, unfortunately, no conclusion or generalization could be drawn for more distal outcomes, such as outcomes included in the child educational domain (e.g., distal or general educational parameters on degrees, school career or dropout). Even though this domain is one of the main priorities for a global, long-term promotion of immigrant youths’ educational and social development, it was not assessed by the studies included in the reviews [40].

3.1.4. Language Learning Interventions

Language learning strategies focused on a second language acquisition. They often encompassed spelling strategies, reading, phonetic and vocabulary exercises and could be supported by music and media tools.

Nevertheless, they shared many characteristics of the academic and cognition interventions, both in terms of their aims and outcomes, even if the content was different, as it focused on linguistic skills instead of broad cognitive skills.

Two reviews presenting language learning strategies described positive effects on language proficiency and communication skills [4,40]. Effects on health outcomes did not seem to be explored.

In general, it has been recognized that intensive instruction in a host country language is extremely important [1], and language learning strategies are common. They do not always qualify as a specific intervention addressing migrant students, as they are often part of wider interventions that adopt other strategies. For example, in some cases, teachers modify texts they need to use during their activities to make them more comprehensible to their students [1].

3.1.5. Educational and Career Support and Counseling, Mentoring and Tutoring

Migrant students are also in need of career guidance. This strategy includes various activities: career advice, career support and counseling, mentoring programs, tutoring programs, certification preparation, support for school qualification, vocational support and training and career coaching [1,36]. These programs, when specifically addressed to migrant students, might feature an emphasis on cultural awareness [1] and can be combined with targeted activities for academic and language remediation, such as lunchtime clubs where students can receive extra help with their coursework [42]. Career advice activities can be carried out in the same facilities that deliver other services, such as the ones for newly arrived students described in the “healthy school policy” component section. For example, Bennouna’s review [36] described a program in which schools had their own refugee welcome center, not only to facilitate student enrolment and orientation, but also to provide tutoring services [43].

Charbonneau [1] highlighted some evidence of positive results for these strategies. Tutoring programs for migrants appeared to help students improve their academics. Mentoring programs found significant changes in the levels of hope and belonging, as well as improved English language skills. Moreover, students’ self-efficacy for academic achievement and assertiveness was found to be improved after career interventions. However, the effects of this strategy were described by only one out of the two reviews included in our research that analyzed educational and career support, mentoring and tutoring interventions.

3.1.6. Health Education and Information

Sometimes, the interventions focused on informing and raising awareness of children and adolescents through health education activities. These interventions were focused on specific health topics, such as oral health or nutrition and usually consisted of classroom activities and lessons delivered by teachers or external professionals. Two reviews analyzed this strategy and its effects on students with migrant backgrounds, with indecisive results. The findings highlighted that it can be modestly effective in improving health-related knowledge and behaviors, but the results about global health, well-being and the access to healthcare were inconsistent [43]. When health education and information is a part of more complex health promotion programs on a specific topic, it is difficult to determine the differential impact of each component. It seems quite clear that this kind of intervention had different effects with targets of different socio-economic statuses, but there was only limited evidence for widening inequalities [41].

3.2. School Physical Environment

None of the strategies to promote migrants’ health and academic outcomes identified by the reviews belonged to this component.

3.3. School Social Environment

We included in this section the strategies to promote migrant students’ health and school adjustment focusing on peer groups and teachers. It is important to notice that some of the strategies included in the other categories could, as a consequence of their implementation, have had some effects on the social environment, for example, creative and expressive techniques when those were shared among students or carried out together with their teachers. The results for those strategies can be consulted in the pertaining sections. Table 3 summarizes the findings about the strategies categorized in the “school social environment” component.

Table 3.

School social environment strategies.

3.3.1. Peer Support

Peer support among students from different backgrounds is aimed at teaching the importance of respecting and welcoming cultural differences, thus affecting the school social environment. This strategy included explicit peer support activities both among migrant groups and within the classroom more broadly. Students would gain knowledge about migrant conditions, share their own stories and traditions in a safe and protected environment, reflect upon stereotypes and discrimination, recognize the resources of others and learn about the importance of intercultural integration, with the idea being to promote a greater understanding among children and adolescents while trying to build self-esteem among minorities. Peers could also help newcomers adjust during their first months, introduce them to new friends and support them in understanding the school rules and functions [36].

Peer activities seemed to positively influence the development of relationships among refugee children and with the children of a host society, along with cultural respect thanks to an identification with other people’s experiences, empathy and a greater sense of agency [17]. However, a peer support strategy could be found in only two of the included reviews, and the potential effects on wider health outcomes or academic outcomes were not mentioned.

3.3.2. Active and Cooperative Learning on Cultural Topics

Active and cooperative learning techniques on topics such as culture, traditions and different habits mainly aimed to teach respect for others and prevent discriminatory attitudes. They could be linked to peer support strategies as they pursued similar goals. They were also clearly connected to the individual level, as they promoted the development of personal competences, and social and emotional skills. Active and cooperative learning activities were adapted and carried out according to the school level. They covered a wide range of issues with a focus on daily life but also addressed identity issues and external topics such as ecology and environmental sustainability habits. This kind of activity can rely on several verbal and non-verbal techniques, since the shared starting point and foundation is one of creating a safe space where students can be active, experiment, and practice actively and cooperatively. Examples of these can be innovative and motivating laboratory activities, the creation of stories and shared representations, interactive discussions on the topics chosen together, a shared analysis and comments on newspapers, tv or radio programs in different languages, multimedia classroom presentations and more generally-inclusive school teaching materials and resources for teaching and learning related to culture, language, and traditions.

The literature reporting on these intervention typologies highlights overall positive findings on both school and health outcomes and favorable results according to their objectives. They positively reduced feelings of distrust and increase children’s senses of agency while making room for a respectful coexistence and expression of empathy [17]. Transforming others’ representations and acknowledging different cultures does improve behaviors, attitudes and better school adaptations, while at the same time, improved school performance and improvements in the valuation and arrangement of school work can be seen [1,38].

3.3.3. Teachers (and School Staff) Training and Support

Teachers and the school staff are clearly another key element of the school social environment. Three reviews analyzed programs that focused on or included teacher training and support, recognizing that educators are especially well-positioned to identify and understand their students’ needs. Providing professional development opportunities for school staff pursued several aims. The idea was usually to enhance teachers’ understandings of the cultural and psychosocial issues affecting migrant children and to counter negative attitudes and stereotypes toward migrant children and adolescents, which in turn was useful for cultivating more inclusive classrooms. Training also promoted specific teaching skills and prepared teachers to deliver program activities [36,40].

Consultation with teachers can be undertaken to provide them with effective strategies for adapting to the needs of migrant students and managing the responses while at the same time supporting them to avoid becoming too distressed. Within this typology of intervention, different methods were then proposed to support and train teachers. Some schools focused on cultural competency training while others emphasized the role of supervision, case discussion and counseling to cope with feelings of helplessness and stress aroused by empathy with migrants’ issues. On occasion, peer support among teachers was also implemented [17].

Teacher training and support generally showed significant effects, mainly on school outcomes [40]. Some authors noted that the training constituted an eye-opener for the teachers, as it helped them to see migrant children and their families from a new perspective [17]. Moreover, the teacher training and support were usually crucial elements of broader, ecological evidence-based programs. Some authors highlighted that training strategies may encounter some barriers, for example, on occasions, school staff might be exclusively focused on reaching teaching goals, and the training hours on health topics can be perceived as too time-consuming. This can also happen because teachers are not always aware of how health and social issue can impact on their students’ abilities to learn [44]. Moreover, some teachers may fear being overwhelmed by the complexity and the emotional burden of dealing with migratory issues, and they might believe they are not capable of dealing with this. Therefore, due to personal characteristics and the coping strategies in place, certain teachers can then be unwilling to consider the specificity of vulnerable groups. On the other hand, some others may become passionate advocates of refugees’ rights [17].

3.4. School Policies

In this intervention typology, we included school policies that can promote the health and school integration of migrant students. Table 4 summarizes the findings about the strategies categorized in the “school policies” component.

Table 4.

School policies strategies.

3.4.1. Orientation, Assessment and Individual Tailoring with Newly Arrived Students

Specific orientation and assessment can be considered as a school policy for newly arrived migrant students but they were only mentioned in one of the included reviews, giving no information about the effectiveness of these strategies [36]. However, Bennouna et al. stated that almost 45% of the programs included in their review described some sort of orientation activity, which in many cases was delivered in conjunction with registration procedures and in combination with other strategies. This type of intervention encompasses orientation interviews to customize educational support for incoming students and to develop a tailored integration plan. In some cases, this school policy also implies specific induction days to introduce students to a school, its procedures, facilities and routines. Some innovative experiences even provide the community in which schools are based with their own welcome centers, which can facilitate migrant students’ enrollment and orientation.

3.4.2. Adoption of Healthy Behaviors at School

In schools, policies can be in place to promote specific behaviors during the time students spend on the school premises. Three reviews described programs or interventions that focused on the adoption of healthy behaviors at school. Examples included the creation of opportunities for physical activity [33], the practice of teeth brushing together at school [39], and the promotion of dietary habits by making healthy food available at school [41]. This strategy was proven effective in modifying the specific behavior addressed, for instance, reducing obesity among students, increasing fruit and vegetable consumption or benefitting children’s oral health [39]. In some cases, the effects of sports and physical activity programs went beyond the improvement of a single target behavior, by also increasing health and well-being prosocial behaviors at a more general level [33]. These very practical initiatives were often implemented as an element of wider interventions that also included informative health education or training activities [41], or arts and music in the case of sports programs [33]. However, as these policies were often addressed to all the students in a school, the degree to which they were effective specifically for migrant students groups was not always clear and we, therefore, cannot affirm if they widened or reduced inequalities and disparities [39,41].

3.5. Health and Social Services

In this intervention typology, we included health services targeted at students with a migrant background and linked to schools. Table 5 summarizes the findings about the strategies categorized in the “health and social services” component.

Table 5.

Health and social services strategies.

3.5.1. Specific Psychological Treatment Interventions

Specific psychological treatment for migrant students was the second most frequently analyzed strategy, as it occurred in nine included reviews. Since it is a specialized treatment, it is carried out by health professionals, usually a clinical team made up of psychologists with the support of social workers, and at times it can be manualized into defined school-based programs [36]. These interventions were developed to specifically address the sequelae of exposure to potentially traumatic events that migrant children and adolescents might undergo, especially if they are exposed to war and conflicts if they are refugees or unaccompanied minors. They are usually implemented as a treatment intervention, as the most common condition affecting migrants is PTSD, but they can also have a preventive focus. CBT therapy, trauma-focused approaches and eye-movement and desensitization therapy (EMDR) are the most recurrent techniques; however, Narrative Exposure Therapy, relaxation techniques and recovery approaches are also widely adopted [34]. Only one review reported on acute interventions for refugee children, and there was little evidence-base to support their use; however, acute interventions include activities such as psychological first aid, debriefing or skills for psychological recovery [34]. These interventions differ according to the moment they are implemented (e.g., with newly arrived people or immediately after a crisis). In terms of content, they usually mixed the other already mentioned strategies, ranging from psychosocial trauma treatment and consultation to art therapies.

Overall, the reviews found that specific treatments led to positive outcomes, particularly in reducing PTSD and depressive symptoms and overcoming pain and suffering due to grief and loss [1,4,30,33,35]. Several further benefits were observed by different studies, namely, specialized therapy that had a positive impact on the overall well-being of migrant children and youths [33] and that significantly reduced functional impairment [35]. Moreover, it showed a reduction in anxiety symptoms and peer problems, and was also effective in treating anger, resource hardship, behavioral and emotional problems, hyperactivity, and peer and conduct problems [9]. Detailing the differential effects of the distinct psychotherapeutic approaches was outside the scope of this umbrella review.

In their study, Fazel and Betancourt [34] pointed out that concrete data was available for individual treatment, while group treatment or preventive treatment were still supported by very limited evidence.

The impact of specialized treatment for migrant students on school and academic outcomes has not been extensively assessed or evaluated, supposedly because this typology of interventions primarily focuses on psychological symptoms. In any case, some improvements in academic performance could be a consequence of increased general well-being, as suggested by Del Pino-Brunet et al. [31], whose research found elements supporting improvements in math performance and language learning.

3.5.2. Integration of Health Services in the School

Three of the reviews included in our study highlighted that some initiatives aimed at providing health services through the school had been put forward. The examples provided a touch upon a wide array of health services that can be integrated in the school, ranging from an on-site mental health unit to treat refugee children referred by their teachers [17], to school dental clinics that provided preventive and restorative dental services for students offering assistance for oral health screening, diagnostics, adjunctive services delivered by dentists and dental hygienists, examinations, fluoride applications, caries treatment upon referral, emergency visits, extractions, etc. [39].

Regardless of the type of clinical solution performed, health services integrated into the school were usually devised to address the underutilization of health services by immigrant children and certain minority groups. In addition, given the prevalence of mental health issues among refugee adolescents and the stigma associated with mental health issues among certain migrant communities, the fact of integrating psychological support directly in schools is very helpful in enhancing the confidentiality and normalization of the disease and for lowering the possibility of patients’ being stigmatized. Since schools are highly trusted and accessed by refugees’ families and youths, this is a powerful approach to diminish the stigma and enhance confidentiality and access to services [45].

Of course, in this area, the immigration context of the host country has a significant influence on what services are offered [17] and the professionals (e.g., dentists, MHPSS experts, nurses, clinicians, and psychologists) involved must be specifically trained [45].

These services generally showed improvements in health among the children served, they were effective in reducing symptoms and increasing health and well-being. A school acts as an accessible location to provide care, for example, school clinics are well accepted by parents and seem to be more productive, efficient and cost-effective. Equity aspects are also relevant, as thanks to their accessibility, services integrated into the school can overcome transportation issues, parents’ availability and general costs; therefore, missed appointments can be greatly reduced in school-based health clinics. However, in some cases, the access rates by eligible students were still lower than expected, leading to mixed results partly attributable to the limited coverage of student populations and the services provided. Moreover, even if they are extremely important for equity, they cannot entirely overcome the challenges of the social determinants of oral health, including poverty, living in a rural location, or gender bias [17,39,45].

3.5.3. Linguistic and Cultural Mediation

For the purposes of our research, we decided to define linguistic and cultural mediation as a separate typology of intervention. Nevertheless, many of the reviews included in our umbrella review referenced some sort of involvement of cultural mediators and interpreters to make other strategies and program implementations more feasible [32,46]. In such cases, those professionals were appointed by the program staff to work with schools [36].

The Herati and Mayer [29] review explored the role of cultural brokers and interpreters in dealing with migrant students. These professionals could intervene both informally to ease the adaptation process for refugee youth and their families or through formal support to connect the refugee youth to mental health practitioners [47]. The results showed that this strategy effectively built a trusting relationship between the school authorities and the marginalized or migrant population. It impacted school inclusion and, in terms of health outcomes, facilitated access to services.

Sometimes, partnering with community organizations and having racially diverse school staff can also be helpful. It is unrealistic, for example, to have professional cultural and linguistic mediators representing every cultural group in schools with high percentages of migrant students from different backgrounds [29].

3.6. Community Links

We included in this component all the interventions addressed toward, or involving, families and the wider community, with the objective to facilitate migrant students’ adjustment and health. It is important to note that it is often difficult to draw a conclusion on the effectiveness of strategies addressing parents since they are almost always implemented in combination with interventions focused on children. Moreover, as parenting programs almost always reach out to parents using different combined strategies, it is hard to say to what extent a specific strategy has an impact compared to other activities engaging students’ families. Table 6 summarizes the findings about the strategies categorized in the “community links” component.

Table 6.

Community links strategies.

3.6.1. Specific Psychological Treatment Addressed to Parents

Interventions for migrants in the school setting can also include specific psychological treatment addressed to parents; yet, this strategy is also linked to the “health and social services” component, which includes specific psychological treatment when addressed to the students themselves. Four reviews included in our study described such interventions from different perspectives, generally showing positive results.

There was evidence of the effectiveness of treatments for parents in reducing psychological symptoms and functional impairments [35] and a significative decrease in children’s behavior problems and parent–child stress was also confirmed [4]. School outcomes were not considered and assessed by the included studies.

3.6.2. Parent Training

Parent training was mentioned in four of the included studies. The training activities embraced several topics, such as a positive parent–child interaction and attachment, parenting skills (e.g., non-violent communication and encouraging children’s academic performance), health related topics and health literacy. The training was also delivered through a variety of formats: group or individual settings, multiple sessions or single sessions [46]. Moreover, the parents could be trained alone or be accompanied by their children during some sessions. A good practice was tailoring the training to family needs, whether these needs arose from culture, values, social disadvantage or child characteristics [48].

Beelmann et al. [40] reported significant effects attributable to parents’ training, particularly for children up to the age of 10, even if the effects seemed smaller than other strategies, such as teacher training. In addition, the effects of this strategy were rarely measured extensively beyond the school or family outcomes. No generalization on the long-term developmental and educational outcomes for immigrant children and adolescents could be made. Gardner et al. [48] performed a meta-analysis of randomized trials of the ‘Incredible Years’ parenting program, covering a range of activities engaging parents. The results showed an overall reduction in child conduct problems, and it was also likely to reduce social disparities thus improving the long term outcomes.

3.6.3. Family Engagement

In this intervention typology, we included strategies to engage migrant students’ families or parents in school activities other than training and specific psychological treatments that have already been analyzed in the respective categories above. Although the focus was centered on serving students, this typology of intervention was described by seven reviews included in our research.

Family involvement in school affairs and contacts with the school staff were facilitated in many ways. For example, projects that engaged migrant parents in the participatory process of assessing and planning the services for their children, or meetings organized with parents and teachers to discuss a family’s experiences with resettling and to understand the parents’ perspectives on how their children were adjusting. The school could also use this opportunity to share information with the parents about activities and services at the school and in the community more broadly [36]. Parents were also engaged directly in a program delivery; for example, Bennouna [36] described an experience in which parents were encouraged to refer youths to services when necessary while working with the parents themselves to reduce the stigma towards mental health and psychosocial support. The parents could also participate in programs and activities designed for their children, sharing experiences, cultural values and traditions [31]. When promoting students’ healthy habits related to nutrition, physical activity or other topics at school, their parents could be involved in assessing the children’s routines and introducing some changes at home as well [41]. Moreover, opportunities could be created for families to participate in specific moments of school life through assemblies or social occasions in which different cultural experiences could then be shared. This kind of activity fosters a sense of belonging to the school community and allows a meeting between very different educational styles and contrasting cultural perceptions of the school’s role in a child’s life [17,34].

Migrant parents’ engagement can be challenging and difficult to sustain, and at times the involvement can be poor or low [41]; however, when family engagement is successful, it can determine very positive results for both the school and health outcomes and can be beneficial for both parents and children.

More precisely, parent support and engagement can improve parenting practices and promote positive parenting and communication. In addition, improvements can then be seen in the parent–child-relationship quality and family functioning, as well as in feelings of security and motivation. Furthermore, lower aggressive behaviors and reduced psychological symptoms levels can also occur [31,34,46].

In terms of school performance, increased attention and improved learning and language skills were observed, together with a generally better academic performance [31,34,46].

Overall, a positive influence on child, parent and family well-being was observed, regardless of the design and methods to obtain the parents’ engagement, if the interventions were well planned, structured and organized [46].

3.6.4. Interventions Involving the Community in the School

Many school-based interventions engage the surrounding community, its services or organizations to some degree; however, this section tries to illustrate the intervention typologies in which community involvement is the main focus. This strategy was present in two reviews considered for this research and usually consisted of assemblies, community volunteer participation in the school activities, the definition of a dialogical inclusion contract with the educational community, and interactive groups. These actions were aimed at transforming the educational and social context through a dialogue and contact with community members who, in many cases, were representatives of other cultures or migrant groups. Generally, they showed favorable results according to their objective, namely, contributing to educational achievements in terms of school outcomes. Regarding health outcomes, some positive results were shown for the development of skills and knowledge on some health topics, but the results were poorer for other health topics. The effects on school attendance and continuation were promising, while family inclusion seemed intermittent [38]. Moreover, this strategy also effectively reduced the stigma associated with mental health among refugees [45].

3.7. Implementation Conditions

The influence of implementation conditions was explored by the included reviews to various degrees of detail.

Taking the implementation conditions into consideration is relevant because they might impact the effectiveness of interventions implemented in a multifaceted and dynamic context [49]. The effectiveness of the strategies depends on how they are implemented, the context in which they are used, the target they reach and the stakeholders they involve [50]. The included reviews did not always analyze the impact of the implementation conditions in depth, but they highlighted some noteworthy aspects. As such, several topics that could hinder or boost a successful implementation emerged. In light of this, an analysis of the implementation conditions can provide helpful indications for explaining and better interpreting the emerging results and identify the preconditions or circumstances necessary to enhance the effectiveness of the interventions.

3.7.1. Multi-Component Interventions

It is recognized that school-wide multi-tiered systems are more effective [1]. Hence, the strategies analyzed in the previous paragraphs were frequently used in combination, and multimodal interventions were common. For example, programs that resorted to group creative and expressive techniques to complement individual psychological treatment for students were found [9], and again, when the skills training was delivered to children, it might also have been accompanied by training for teachers or families [40]. Different authors generally agreed that drawing upon multi-component interventions manages migrant students’ needs with impacts that are definitely higher than implementing a single strategy. School-based programs that targeted multiple levels of determinants, for example, may have been more effective than those that targeted only one level. Moreover, they may have been more equitable in terms of health and education outcomes and more just for children throughout the social gradient [39]. Ecological models of interventions addressing the whole-school environment also provided a systemic understanding of the interactions among the different players [17].

However, using more than one strategy is no guarantee of success per se [30,40]. Moreover, not all the programs to promote migrants’ health and well-being were able to adequately attend to the interplay of individual and structural factors influencing immigrant students’ educational experiences and outcomes [4].

A critical aspect of multi-component interventions lies in the assessment and evaluation of their effectiveness. Because of the variety of services included, it is difficult to conclude which elements of an intervention have the greatest impact on improvements in functioning [35]. In addition, for some program combinations, very high heterogeneity of effects can be found, suggesting the presence of further important effect-size moderators [40].

3.7.2. Human Resources

Teachers and school staff are an essential point of reference for their students and represent the primary resource to identify and understand migrant students’ needs [36]. In some cases, they are also in charge of delivering health promotion activities and they are responsible for effective classroom behavior management, which is a critical component of equitable education [51]. In light of this, staff involvement is crucial; however, since schools are often financially under-resourced, strategies that require considerable staff time and clinical space can be difficult to afford [36]. Beyond financial issues, the development of trusting and collaborative relationships between program staff and schools takes time, patience and adaptability on all sides and it is important to negotiate clear limits before implementation and to review them among school and program staff regularly. Sharing the objectives of interventions among the human resources involved is also crucial. At times, teachers and school staff do not have a strong understanding of the link between health and learning and are not aware of how social and emotional difficulties could compromise students’ abilities to learn; therefore, educators can feel like they lack the time or administrative support to take care of health and inclusion interventions or to attend specific trainings. Changing the school culture can be of utmost importance. Moreover, a helpful strategy includes appointing a staff person to coordinate activities and facilitate the collaboration within the school and with other partners [36].

3.7.3. Co-Design and Stakeholders’ Participation

The partnership with the surrounding community is key to supporting implementation, even though building it can be difficult. Concerning parents’ participation, the precariousness of refugee families and social environments hinders their capacity to become fully involved in the development of such programs [17]. As for the wider community, the importance of encouraging participation and making activities “with” migrant groups instead of “in” them has been emphasized; interventions developed in contexts where schools and communities collaborate are relevant and successful [29,38]. Moreover, community institutions can act as mediators between schools and students’ families, especially when feelings of distrust are present. For example, community leaders may provide bridging and networking for more isolated families [17]. Despite these considerations, however, some reviews noted that many studies did not report on collaborations with stakeholders, especially during the design stage of interventions [33]. As Bennouna et al. [36] clarified, successful strategies for engaging families and broader communities in programming efforts were likely to differ substantially across contexts and migrant groups. Consequently, more research is needed to guide the development of partnerships.

3.7.4. The Use of Technology

The use of technology can support and facilitate activities with migrant children. Different authors agreed that, if used correctly, technologies and new media represent a useful tool to promote inclusion, overcome educational barriers, prevent radicalization and learn about other cultures and social values [31,38].

Some promising results showed improvements in language vocabulary and coding skills, as well as better executive functioning and decreased hopelessness. For example, digital storybooks seemed more effective in teaching expressive vocabulary than static books for this population, and computer collaborative learning was associated with a higher reading comprehension [1].

3.7.5. Assessment and Evaluation

For a successful implementation, an initial phase of a needs analysis or assessment and a proper evaluation of an intervention is pivotal.

School-based programs should screen the population of interest to determine their health and well-being levels to select suitable strategies and make a correct implementation possible. Nonetheless, screening in isolation only provides data for monitoring without improving the outcomes of interest [39].

With respect to evaluation, some authors noted that the existing services and programs developed by schools were often not evaluated rigorously, either qualitatively or quantitatively. A lack of grounding in theory and the absence of a careful evaluation may hinder the proposed initiatives. On the other hand, focusing only on a rigid protocol may also be a mistake, as health professionals’ preoccupation with evidence-based treatments may hamper the already slow development of alternatives to mainstream practices. These could, however, provide a wider array of programs addressing the different cultural and contextual needs of migrant families [17].

3.7.6. The Debate on Cultural Adaptation

The authors of the included reviews held very different positions on whether activities should be adapted to the needs of this population of children and adolescents.

On one side, some findings indicated that individual and culturally tailored programs were effective to promote the health and academic outcomes of migrant students [40]. The studies supporting this perspective underlined the need for tailoring based on a richer understanding of young migrant people’s lived experiences, socioeconomic status, ability status, gender, developmental age, citizenship status, and a host of additional distinguishing characteristics. Moreover, they believed that successful program adaptation also depends on reaching students and their families in a manner that coheres with their beliefs, practices, identities, and idioms [36]. They highlighted that evidence suggests that cultural adaptation has the potential not only to enhance an intervention’s effectiveness, but also its relevance and feasibility [52].

However, on the other side, contrasting results showed that, when selecting a program targeted to immigrants, it may be more important to choose a well-studied intervention with evidence of effectiveness than to create resource-consuming cultural adaptation actions [46]. From this perspective, rather than being specifically culturally adapted, programs should be collaborative and flexible in their approach [48]. This idea was also supported by the observation that environment-focused interventions without any apparent cultural tailoring positively affect children’s lifestyle behaviors [52].

Moreover, some authors believed that not only was the cultural adaptation not necessary, but that some program characteristics should not even be seen as crucial as they did not have an impact on the practical effectiveness of the activities. In fact, regardless of the design and methods, interventions that were well structured, planned and organized can be beneficial [46]. Apart from the preventive approach or type of program chosen, only a few characteristics, such as the intervention format, seemed to be significant moderators. Other elements, as for example the type of administrator, the program length, or the training and supervision of the executor, did not determine a significant impact [40].

Even when choosing to adopt cultural adaptation, the process is not easy and no standard procedures are in place. Challenges can arise from difficulties in communicating with parents and communities to having fundamental differences over parenting concepts, educational achievement, and mental health. Moreover, as students are frequently dropping out and other newcomers arriving, it can be difficult to plan and deliver services that could meet everyone’s varying needs, especially when the population of students cannot participate consistently and continuously [36].

Many adaptation strategies depend on the population particularities but also on the size, capacities, and preferences of the schools and school districts. When carried out, tailoring is often related to the intention to participate, acceptability, adherence and to reduce dropouts. It is important to note that few studies reported on the methods used to conduct cultural tailoring [46], even though several programs took measures to adapt culturally. A commonly mentioned method was engaging program staff of the same ethnic, linguistic, or national background as the students being served. Individual student assessments were also used to tailor their service provision accordingly. These methods might be promising but can be extremely demanding, especially in highly heterogeneous communities [36]. Other relevant methods described in the literature were community-based participatory research or qualitative approaches [46]. In the particular case of specific psychological treatment, professionals may struggle to reconcile the demands of evidence-based clinical practices that assume treatments tested in clinical samples can be transferred across contexts, with the complex and under-researched needs of migrant children and adolescents. A response that was experimented with was selecting only some components of a treatment model, but this implied departing from the evidence-based model originally intended to be used [15].

4. Discussion

Since the literature on school-based strategies targeting migrant students is limited [4,9] and evaluations are needed in order to understand which activities are useful for migrant students [17], the current umbrella review examined the effectiveness of school-based strategies aimed at promoting migrant students’ health and academic outcomes. Twenty-one reviews were analyzed, and 18 strategies were identified and classified into the six components of the Health Promoting School model: individual skills, school physical environment, school social environment, school policies, health and social services, and community links. The present study contributes to demonstrating that the whole-school approach proposed by the Health Promoting School model for health promotion is a fitting framework to interpret the strategies addressing migrant students’ needs. This helps to fulfil the research gap identified by Nyika et al. [5], who highlighted the scarcity of knowledge on the impact of the HPS approach on immigrant school populations.

This study confirms the HPS approach’s value in providing a vision to guide educational systems [53], together with its flexibility and potential to address different emerging issues [23]. It was possible to categorize the identified strategies based on the logical framework of the components, thus reflecting an overview of the main elements addressed by studies in the field in order to achieve migrant students’ health and academic success. The distribution of the strategies over the six components shows that all areas except for one are covered. This result is coherent with the HPS vision, according to which, by addressing health and well-being simultaneously through the six components, they reinforce each other making the efforts to promote health more effective [21]. These findings strengthen the previous literature’s results, confirming how immigrant youth’s needs cannot be addressed at the individual level only [11], but greater consideration should be given to the social environment to address the complex interaction between individual and structural factors [4].

The only whole-school approach component to which none of the identified strategies belonged was the one related to the “school physical environment”. That does not necessarily mean that this component was neglected because it is less important, but rather that the primary studies’ specific objectives were pursued by focusing on other components. In fact, modifications to the school physical environment were of utmost importance to promote behaviors such as physical activity among the whole student populations, but they might not be the first priority when targeting the vulnerabilities of migrant students.

The relevance of the HPS approach to address migrant students’ needs is also confirmed by the fact that the effective implementation conditions observed by the reviews were consistent with and confirmed the HPS pillars: a whole-school approach to health, participation, school quality, evidence and school and community collaborations [18,54]. The component that accounts for the higher number of strategies is “individual skills” and the most analyzed strategy, namely, creative and expressive techniques, is placed within this component. Expressive techniques seem to be an effective strategy, especially on psychosocial outcomes. They also positively impact school performances, even though educational outcomes are less explored. A relevant number of reviews also mentioned skills training techniques; these address a very high number of objectives and have shown positive results on some dimensions related to physical, social and emotional health and academic outcomes.

Psychological needs also seem to be effectively managed through some strategies pertaining to the “health and social services” component, such as specific psychological treatment and the integration of health services in the school setting. Given the prevalence of traumatic experiences and adjustment issues among migrant students, this result could be expected. School health services and psychological interventions can also determine improvements in school outcomes as a consequence of an increased overall well-being.

The area referred to community is also central, and four frequently analyzed strategies could be included in this component. Strategies involving families and the broader community are usually delivered jointly and seem to have positive effects in terms of inclusion. The relevance of engaging the community when dealing with migrant youths is corroborated by the fact that stakeholder participation and intervention co-designs also emerged in various reviews as key factors for a successful implementation. Family and community engagement strategies can be effective on school outcomes, mainly in terms of improved performance, learning and language skills, and increased attention and school attendance.

The three strategies included in the “school social environment” component appear to have a role in bolstering relationships among migrant students, native students and teachers through acceptance and cultural respect. Among these strategies, teacher training seems to be particularly beneficial with respect to academic outcomes. It must be noted that the school social environment does not focus only on relationships among peers and teachers but also considers the whole school staff; however, in the current literature, there is little discussion on how school-based interventions for migrant students actually engage all school community members. Even when the wording “school staff” was mentioned, it often only referred to the teachers. As a matter of fact, only one review that emerged from our search briefly mentioned activities carried out by all people who were a part of the school. In particular, it referred to the consultation and engagement of the school staff for a participatory assessment of the schools’ capacities and culture [36]. This consultative approach when implementing a program can create a sense of belonging and joint ownership that could be crucial for implementation.

Strategies attributable to the “school policies” component appear to be explored less extensively. They could have promising outcomes in terms of health behaviors, presumably impacting positively on the entire student population, with migrants included. No evaluation was available with reference to school policies specifically addressed to migrant students only.

The strong stress on the importance of multicomponent programs heads towards the direction of a comprehensive systemic approach. However, it must be noted that only in some cases did the identified interventions seem to integrate the action on health outcomes and on academic outcomes or to evaluate both dimensions. There is often a tendency to focus assessments and evaluations exclusively on one of the two aspects. This result confirms what was already observed by Langford et al. [55,56] with reference to evaluation studies on HPS implementation. They highlighted that educational impacts are rarely reported within otherwise robust evaluations of the HPS framework. In addition, many strategies do not seem to be able to impact both, with a prevalence of strategies that focus mainly on health and psychosocial outcomes and fewer strategies that only address academic outcomes. Although this must be partially explained by the specific aims of the selected reviews, it would be important to understand to which extent the available interventions were trying to enhance migrant youths’ health and school achievements at the same time. This is even more true if we think about the school setting, where health and psychosocial outcomes are inextricably linked to school and academic outcomes.