Sustainable Management of Marine Biodiversity in Areas beyond National Jurisdiction by Establishing Protected Areas on the High Seas: A Chinese Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Status Quo of Protection and Governance of Marine Biodiversity

2.2. Facing Grave Threats

2.2.1. Fishing

2.2.2. Shipping

2.2.3. Deep-Sea Mining

2.3. Status Quo of Relevant International Governance Regimes

2.3.1. The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA)

2.3.2. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations

2.3.3. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

2.3.4. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

2.4. A Feasible Conservation Tool: The Establishment of MPAs

2.4.1. Current Practice of High Seas MPAs

2.4.2. A New Legally Binding Instrument on BBNJ

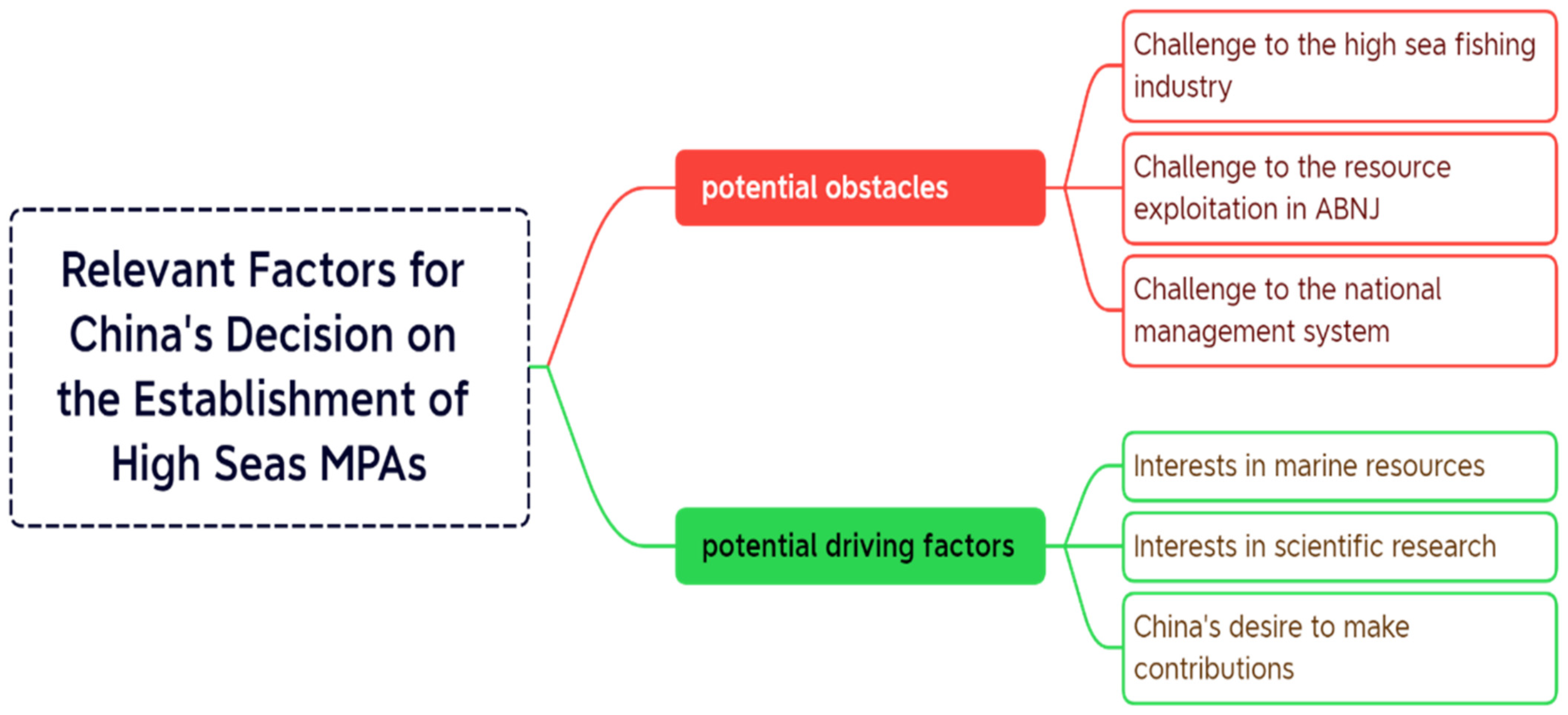

2.5. Relevant Factors for China’s Decision on the Establishment of High Seas MPAs

2.5.1. The Challenge to the High Sea Fishing Industry

2.5.2. The Challenge to Resource Exploitation in ABNJ

2.5.3. The Challenge to the National Management System

3. Analysis of Stimulative Factors

3.1. Interests in Marine Resources

3.2. Interests in Scientific Research

3.3. China’s Desire to Make Contributions to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ban, N.C.; Maxwell, S.M.; Dunn, D.C.; Hobday, A.J.; Bax, N.J.; Ardron, J.; Gjerde, K.M.; Game, E.T.; Devillers, R.; Kaplan, D.M.; et al. Better Integration of Sectoral Planning and Management Approaches for the Interlinked Ecology of the Open Oceans. Mar. Policy 2014, 49, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See Marine Protected Areas. Available online: https://www.protectedplanet.net/en/thematic-areas/marine-protected-areas (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture—2008; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture—2012; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Global Environment Outlook 5. Available online: http://www.unep.org/resources/global-environment-outlook-5 (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Global Biodiversity Outlook 3; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2010; ISBN 978-92-9225-220-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, A.D.; Laffoley, D. Introduction to the Special Issue: The Global State of the Ocean; Interactions between Stresses, Impacts and Some Potential Solutions. Synthesis Papers from the International Programme on the State of the Ocean 2011 and 2012 Workshops. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 74, 491–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brondízio, E.S.; Settele, J.; Diaz, S.; Ngo, H.T. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, N.C.; Bax, N.J.; Gjerde, K.M.; Devillers, R.; Dunn, D.C.; Dunstan, P.K.; Hobday, A.J.; Maxwell, S.M.; Kaplan, D.M.; Pressey, R.L.; et al. Systematic Conservation Planning: A Better Recipe for Managing the High Seas for Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Use. Conserv. Lett. 2013, 7, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárcamo, P.F.; Garay-Flühmann, R.; Squeo, F.A.; Gaymer, C.F. Using stakeholders’ perspective of ecosystem services and biodiversity features to plan a marine protected area. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 40, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan, O. How to save the high seas. Nature 2018, 557, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.M.; Kolding, J.; Rice, J.; Rochet, M.-J.; Zhou, S.; Arimoto, T.; Beyer, J.E.; Borges, L.; Bundy, A.; Dunn, D.; et al. Reconsidering the Consequences of Selective Fisheries. Science 2012, 335, 1045–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.M. Deep impact: The rising toll of fishing in the deep sea. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2002, 17, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, P.; Jensen, O.P.; Hutchings, J.A.; Baum, J.K. Resilience and Recovery of Overexploited Marine Populations. Science 2013, 340, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worm, B.; Tittensor, D.P. Range contraction in large pelagic predators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11942–11947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.; Watson, R.; Morato, T.; Pitcher, T.; Pauly, D. Intrinsic Vulnerability in the Global Fish Catch. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007, 333, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichsen, D. The Atlas of Coasts & Oceans: Ecosystems, Threatened Resources, Marine Conservation; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-226-34226-9. [Google Scholar]

- Nowacek, D.P.; Thorne, L.H.; Johnston, D.W.; Tyack, P.L. Responses of Cetaceans to Anthropogenic Noise. Mammal Rev. 2007, 37, 81–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Second World Ocean Assessment; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Klimont, Z.; Smith, S.J.; Cofala, J. The last decade of global anthropogenic sulfur dioxide: 2000–2011 emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 014003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. From Pollution to Solution: A Global Assessment of Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution (Synthesis); UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Llodra, E.; Tyler, P.A.; Baker, M.C.; Bergstad, O.A.; Clark, M.R.; Escobar, E.; Levin, L.; Menot, L.; Rowden, A.; Smith, C.R.; et al. Man and the Last Great Wilderness: Human Impact on the Deep Sea. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaskill, M.; Scientific American. How Much Damage Did the Deepwater Horizon Spill Do to the Gulf of Mexico? Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-much-damage-deepwater-horizon-gulf-mexico/ (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- International Seabed Authority. Note on Public Information on Plans of Work for Exploration. Available online: https://isa.org.jm/note-public-information-plans-work-exploration (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Niner, H.J.; Ardron, J.A.; Escobar, E.G.; Gianni, M.; Jaeckel, A.; Jones, D.O.B.; Levin, L.A.; Smith, C.R.; Thiele, T.; Turner, P.J.; et al. Deep-Sea Mining With No Net Loss of Biodiversity—An Impossible Aim. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dover, C.L.; Ardron, J.A.; Escobar, E.; Gianni, M.; Gjerde, K.M.; Jaeckel, A.; Jones, D.O.B.; Levin, L.A.; Niner, H.J.; Pendleton, L.; et al. Biodiversity Loss from Deep-Sea Mining. Nat. Geosci. 2017, 10, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santillo, D. An Overview of Seabed Mining Including the Current State of Development, Environmental Impacts, and Knowledge Gaps. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 4, 24. [Google Scholar]

- UNGA. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 17 November 2004; UNGA: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- UNGA. Report of the Preparatory Committee Established by General Assembly Resolution 69/292; UNGA: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNGA. International Legally Binding Instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction; UNGA: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Intergovernmental Conference on Sustainable Use of Marine Biodiversity to Hold Fourth Session at United Nations Headquarters, 7–18 March. Available online: https://www.un.org/press/en/2022/sea2138.doc.htm (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- UNGA. Draft Report of the Intergovernmental Conference on an International Legally Binding Instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction; UNGA: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. International Plan of Action for Reducing Incidental Catch of Seabirds in Longline Fisheries. International Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Sharks. International Plan of Action for the Management of Fishing Capacity; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. International Guidelines for the Management of Deep-Sea Fisheries in the High Seas. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i0816t/i0816t00.htm (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- CBD. Report of the Expert Workshop to Identify Options for Modifying the Description of Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas and Describing New Areas; CBD: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ecologically or Biologically Significant Areas (EBSAs) Philippine Clearing House Mechanism. Available online: https://www.philchm.ph/ecologically-or-biologically-significant-areas-ebsas/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- See Aichi Biodiversity Targets. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- CBD. Provisional Agenda. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, Kunming, China; Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–15 October 2021; Kunming, China, 2021; p. 2. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/9316/afac/9eb22320f68f51aa8c815e66/cop-15-01-rev1-en.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982. Available online: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/UNCLOS-TOC.htm (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Gjerde, K.M. Regulatory and Governance Gaps in the International Regime for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biodiversity in Areas beyond National Jurisdiction; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Game, E.T.; Grantham, H.S.; Hobday, A.J.; Pressey, R.L.; Lombard, A.T.; Beckley, L.E.; Gjerde, K.; Bustamante, R.; Possingham, H.P.; Richardson, A.J. Pelagic protected areas: The missing dimension in ocean conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toonen, R.J.; Wilhelm, T.; Maxwell, S.; Wagner, D.; Bowen, B.W.; Sheppard, C.R.; Taei, S.M.; Teroroko, T.; Moffitt, R.; Gaymer, C.F.; et al. One size does not fit all: The emerging frontier in large-scale marine conservation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 77, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochette, J.; Wright, G.; Gjerde, K.M.; Greiber, T.; Unger, S.; Spadone, A. A New Chapter for the High Seas? IDDRI-Issue Brief IASS Work. Pap. 2015, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.; Rochette, J.; Greiber, T. Sustainable development of the oceans: Closing the gaps in the international legal framework. In Legal Aspects of Sustainable Development: Horizontal and Sectorial Policy Issues; Mauerhofer, V., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 549–564. [Google Scholar]

- UNGA. Revised Draft Text of an Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction; UNGA: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Paper. “Diverse Creatures Protect the Home of the Earth.” Outlook. 2022. Available online: https://m.thepaper.cn/baijiahao_18202446 (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Baidu. “Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) for National Economic and Social Development and Vision 2035 of the People’s Republic of China”. Available online: https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E4%B8%AD%E5%8D%8E%E4%BA%BA%E6%B0%91%E5%85%B1%E5%92%8C%E5%9B%BD%E5%9B%BD%E6%B0%91%E7%BB%8F%E6%B5%8E%E5%92%8C%E7%A4%BE%E4%BC%9A%E5%8F%91%E5%B1%95%E7%AC%AC%E5%8D%81%E5%9B%9B%E4%B8%AA%E4%BA%94%E5%B9%B4%E8%A7%84%E5%88%92%E5%92%8C2035%E5%B9%B4%E8%BF%9C%E6%99%AF%E7%9B%AE%E6%A0%87%E7%BA%B2%E8%A6%81/56266255?fr=aladdin (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Yaping, M.; Ying, J. From the Evolution of ‘High Sea Fishing Freedom’ Principal See the Trend of the Governance of Ocean Fisheries. China Ocean. Law Rev. 2005, 1, 67–78. Available online: http://lib.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=42132243 (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Wang, D.; Wu, F. China Fishery Statistical Yearbook 2021; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 2021; ISBN 978-7-109-28300-8. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Fishery of the Ministry of Agriculture. China Marine Fishery Statistical Yearbook; Department of Fishery of the Ministry of Agriculture of the PRC: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Jiang, L.; Fan, X.; Luo, T.; Gong, Y.; Wang, Q. Research on establishment of marine protected areas on the high seas by China. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 38, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, E. World’s Population Will Continue to Grow and Will Reach Nearly 10 Billion by 2050. 2019. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/worlds-population-will-continue-grow-and-will-reach-nearly-10-billion-2050 (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- UNGA. 71/312. Our Ocean, Our Future: Call for Action; A/RES/71/312; UNGA: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Ross Sea Region Marine Protected Area | OSPAR Marine Protected Areas | South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf Marine Protected Area | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Management Authority | CCAMLR | OSPAR Commission/Contracting Parties | CCAMLR |

| Governance Type | Joint governance | Collaborative governance | Joint governance |

| Related Legal Documents | Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources | OSPAR Convention | Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, M.; Huang, Y.; Fu, Q. Sustainable Management of Marine Biodiversity in Areas beyond National Jurisdiction by Establishing Protected Areas on the High Seas: A Chinese Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031927

Yu M, Huang Y, Fu Q. Sustainable Management of Marine Biodiversity in Areas beyond National Jurisdiction by Establishing Protected Areas on the High Seas: A Chinese Perspective. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):1927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031927

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Minyou, Yuwen Huang, and Qinghua Fu. 2023. "Sustainable Management of Marine Biodiversity in Areas beyond National Jurisdiction by Establishing Protected Areas on the High Seas: A Chinese Perspective" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 1927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031927

APA StyleYu, M., Huang, Y., & Fu, Q. (2023). Sustainable Management of Marine Biodiversity in Areas beyond National Jurisdiction by Establishing Protected Areas on the High Seas: A Chinese Perspective. Sustainability, 15(3), 1927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031927