Abstract

Nowadays, post-90s employees are becoming the main cohort within organizations in China. They are considered to have strong self-awareness, weak collective consciousness, and low work motivation, making it difficult for managers to improve their job performance. After reviewing the relevant literature, we found that person–organization (PO) value fit is positively related to job performance, but there is a limitation in explaining the psychological characteristics of post-90s employees. This study aims to explore the mechanism that how PO value fit impacts the job performance of post-90s employees in China. From the view of self-determination theory (SDT), we selected happiness as a mediating variable and love of money (LOM) as a moderating variable. Based on valid data collected from 919 employees from all walks of life in China, we utilized both linear regression analysis and a bootstrapping approach to verify our propositions. The results revealed a positive relationship between PO value fit and job performance through happiness. The moderated mediation analysis further indicated that the mediated path bonding happiness with job performance was weaker for post-90s employees with higher levels of LOM. The present study offers a nuanced interpretation of how PO value fit affects the job performance of post-90s employees in China and contributes to providing suggestions for improving the sustainability of organizations.

1. Introduction

The job performance of employees is a key determinant of an organization’s competitive success and sustainability. In recent years, there have been more and more post-90s entering the workplace and becoming the main force promoting organizational development. Compared with previous generations in China, most post-90s employees are the only children of their families, and grew up in a period of rapid economic development brought about by reform and the opening up of China [1]. Thus, they have distinctive psychological and behavioral characteristics. Generally, post-90s employees are open-minded, enjoy challenging activities, and are knowledgeable, which causes their organizations to become vibrant and innovative. However, they also have strong self-awareness, weak collective consciousness, and low work motivation, which makes it difficult for them to make sustainable contributions to their organization [2]. How to stimulate enthusiasm and improve the job performance of post-90s employees has been a great challenge for managers.

As an important topic in the field of organizational behavior and human resource management, person–organization (PO) value fit has attracted widespread attention from researchers and managers in China and abroad. It refers to the similarity between the values of employees and organizations [3,4] and has provided insight into approaches to improve post-90s employee job performance. Some investigators have postulated that employees who experience a high PO value fit are more likely to show higher job performance [5,6]. However, there is a limitation in the single PO value fit model, in that it can no longer fully explain the psychological characteristics of post-90s employees. Therefore, it is necessary to verify the association between PO value fit and job performance of post-90s employees and further explore what the impacting mechanism is.

Given that post-90s employees grew up in a relatively rich material environment, lacking the motivation to make money through hard work and for most of them, work not only represents a source of income for survival, but also is an approach to pursuing their happiness, improving their abilities, and realizing their self-worth [2], this study expects love of money (LOM) and happiness to be crucial factors. To clarify the impact of the mechanism of PO value fit on job performance, this study further regards LOM and happiness as moderators of mediating contingencies according to the self-determination theory (SDT).

SDT is a macro theory that examines personality and human motivation [7]. It can provide a theoretical framework explaining how PO value fit affects the job performance of post-90s employees. Firstly, SDT believes that all human beings have three basic psychological needs, namely autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Autonomy refers to an individual’s need for free choice in their behavior; competence involves an individual’s need for impacting their own output and what is going on around them; and relatedness is an individual’s need for emotional support from the surrounding environment or others. This is particularly applicable to analyzing the psychology of post-90s employees. Making independent judgments and focusing on self-worth based on self-awareness is the expression of post-90s employee need for autonomy. The preference of challenges is the concrete manifestation of the competence need for post-90s employees to “prove that they can do it”. While the relatively weak collective consciousness reflects the unique relatedness need of post-90s employees. Secondly, SDT differentiates autonomous motivation and controlled motivation and focuses on the links between different types of motivation and job performance in organizations. Autonomous motivation embodies relative freedom of will and action; while controlled motivation refers to thinking about what others might think, or how the outside evaluates [8,9]. Generally, autonomous motivations bring about better performance than controlled motivations [10,11]. Individuals driven by autonomous motivation tend to be more self-regulating; actively choose new, interesting, and challenging activities; and take responsibility. On the contrary, those driven by controlled motivation are inclined to be dependent on the demands of others and give priority to money, honor, status, and other external factors [8,9], producing short-term gains on targeted outcomes and having negative effects on subsequent performance [12]. This provides ideas for understanding PO value fit from a motivational perspective. Finally, SDT focuses on the intrinsic and extrinsic factors that support or hinder employee’s three basic psychological needs and suggests that multiple factors, including job design, managerial styles, and pay contingencies, that meet the three basic psychological needs, will lead to increased satisfaction and thriving of employees, as well as collateral benefits for organizational effectiveness [12]. Inversely, when these needs are blocked, employees will develop functional disorders and their work motivation and happiness will be drastically reduced. This explains the role that LOM and happiness play in the relationship between PO value fit and job performance.

In summary, to improve the job performance of post-90s employees, this study aims to explore the impacting mechanism of PO value fit on the job performance of post-90s employees based on SDT.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Implications of PO Value Fit toward Job Performance

Personal values are beliefs that guide a person to make decisions and behavior choices, while organizational values are norms that guide an organization to allocate resources and constrain its members [13]. PO value fit, as mentioned above, is the similarity between the personal values of employees and organizational values [3,4]. It is a criterion for employees to guide work behavior, evaluate work value, and measure whether their goals are in line with organizational expectations [14].

By employing SDT, PO value fit can act as an autonomous motivator. Conceptually, autonomous motivation is characterized by an individual being engaged in an activity with a full sense of willingness, volition, and choice [9]; while PO value fit reflects the degree to which personal values of employees fit with organizational values and can be expressed through the process of identifying and internalizing organizational values [15]. Previous studies have shown that when employees identify with the worth and purpose of their organizations, they are likely to become more autonomously motivated and reliably perform better [12]. This indicates that if an employee fits well with his/her organization in terms of values, they are more likely to exhibit a certain behavior based on their own will and free choice at work. Moreover, through the course of sharing values and identification, employees are further entrusted with greater responsibilities, made to feel more empowered, and accustomed to viewing the organization’s successes and failures as their own [16]. Inversely, those misfit employees are more likely to experience controlled forms of motivation, leading to lower job performance.

In addition, PO value fit can influence employee job performance by satisfying their three basic psychological needs [17,18]. First, PO value fit supports the autonomy of employees by organizations in a variety of ways, including considering employee perspectives, providing opportunities for input, and sharing information across organizational levels, thereby promoting job performance [18]. Second, a high degree of PO value fit brings about a sense of competence for employees, and their work confidence and ambition are enhanced [19], thus creating better job performance. Third, PO value fit facilitates the employee’s sense of relatedness. It supports similar values among employees and strengthens the emotional connection between the organization and its employees [20]. In turn, employees feel harmonious and tend to interact with others in a way that promotes effective communication, mutual trust, and common perspectives [14,21], making teamwork more efficient.

Therefore, we speculate that perceived value fit may rule as an autonomous motivator that can directly improve employee job performance by satisfying the three basic psychological needs. Based on this, we formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

PO value fit plays a crucial role in positively predicting job performance.

2.2. The Mediating Role of Happiness

There are also reasons to expect a mediated mechanism in the relationships between PO value fit and job performance. In this study, we put happiness at the forefront. Happiness, an eternal topic, is aspired to by all human beings and understood as the ultimate goal from a philosophical point of view. In the view of SDT, happiness is better described in terms of thriving or being fully functioning [7] rather than merely by the presence of positive feelings and absence of negative ones [22]. Thriving is characterized by vitality, awareness, access to, and exercise of one’s human capacities, and true self-regulation. Individuals who are fully functioning enjoy a free interplay of their faculties in connecting with both their inner needs and states [7].

SDT holds that all human beings progress inherently toward psychological growth, internalization, and happiness and the three basic psychological needs are essential for happiness and facilitating effective functioning. Specific environmental elements such as the degree of congruity between personal attributes and contextual factors can either facilitate or hinder psychological need satisfaction [12]. Employees in value-aligned organizations will boost a sense of autonomy [23], competence [24], and relatedness with their organization [25]. This indicates that when employees work in an organization characterized by congruent values, organizations are more likely to provide environments that allow employees to have their three basic psychological needs met, while the satisfaction of the three needs yielded greater happiness. Previous research has also found that happier employees are more likely to be encouraged intrinsically and to be more autonomous and creative, which contributes to better job performance [26], forming a virtuous circle between employees and their organization. Thus, we establish a foundation regarding PO value fit, happiness, and job performance as follows:

Hypothesis 2.

Happiness plays a mediating role in the relationship between PO value fit and job performance.

2.3. Love of Money as a Moderator

In addition to the indirect effects on job performance via happiness, PO value fit could also have an indirect impact on job performance through potential moderators. Research examining possible moderators of the relationships between PO value fit and work-related outcomes has identified a multitude of variables, with personality traits [27], demographic characteristics [28], and situational variables [29] included. We propose that the mediated effects of happiness on PO value fit and job performance can be partially explained by considering the desire for money.

Money is a vital element of human life and a sign of personal wealth. Each of us spends most of our life making and spending money. Money is such a crucial issue in this material world on account of its economic function (a medium of exchange, etc.) and psychological function (a symbol of achievement, respect, and power, etc.) [30] that it has been widely recognized as a motivator to attract and retain employees in organizations. When money was taken into account, numerous results have shown that those making higher wages were happier in their lives than those making lower wages because money can be exchanged for goods that increase one’s utility [31,32]. Moreover, many studies have found an inverted U-shaped relationship between money and happiness [33,34], indicating a “diminishing marginal utility”. Specifically, when an individual has much money, his/her happiness increases, however, when money is enough to cover his/her daily expenses, no matter how much money an individual has, his/her happiness does not increase.

Nevertheless, happiness does not necessarily depend on what individuals have, but rather on their attitudes. Human beings have ambivalent attitudes toward money. On the one hand, there are many idioms meaning “money is the root of all evil” [35]. On the other hand, many people are still focused on achieving material success and regard the accumulation of money and material possessions as a basic life goal [36]. Different attitudes toward money can cause individuals to have different perceptions of happiness even when they possess the same amount of money. Therefore, happiness may not be well explained by rising incomes because money desires are also rising. In other words, the more we obtain, the more we want. Although employees with higher incomes are somewhat happier than those with lower incomes, if those with higher incomes are strongly extrinsically oriented in their aspirations, they are less happy than those with lower incomes who do not overvalue money [31]. Based on this, some researchers are more focused on the influence of LOM rather than income, on happiness.

As one of the most commonly used constructs in money psychology, LOM is captured as a multi-dimensional variable, including affective, behavioral, and cognitive components [37]. It is operationalized by the LOM scale, which consists of three factors: richness, motivator, and the importance [38]. The richness dimension reflects one’s affection (i.e., love or hate orientation, feeling, or emotion) toward money. The motivator dimension measures one’s intention to move forward toward a money target. The importance dimension captures one’s key beliefs, ideas, or money values. A strong desire for more money is negatively correlated with happiness [33]. Those individuals with high LOM, possess greater desires for satisfying their physiological and psychological needs [39] and believe that money can not only meet their basic survival needs but also give them power [40], buy happiness [41,42], and signal their feelings of success [43]. As a result, they are more likely to make far more money than they require [44]. However, from the SDT perspective, when individuals are obsessed with external monetary contingencies, less attention is distributed to acquiring the three basic psychological needs that are fundamental to enhancing their happiness [15].

Nevertheless, LOM is not always coupled with perishing consequences. To some, it is an accelerator. Referring to SDT, LOM represents an extrinsic motivation that can powerfully compel or seduce individuals into action in an immediate sense [7]. LOM can also promote career advancement and personal financial optimism, as individuals will go to any length to achieve their objectives until they achieve ultimate success [45]. This means that when the motivator of LOM functions, employees achieve goals effectively and efficiently [35]. Building upon the motivational property of LOM, the interaction effect on the positive relationship between happiness and job performance is hypothesized as follows:

Hypothesis 3.

LOM lessens the significance of PO value fit in affecting job performance by diluting happiness.

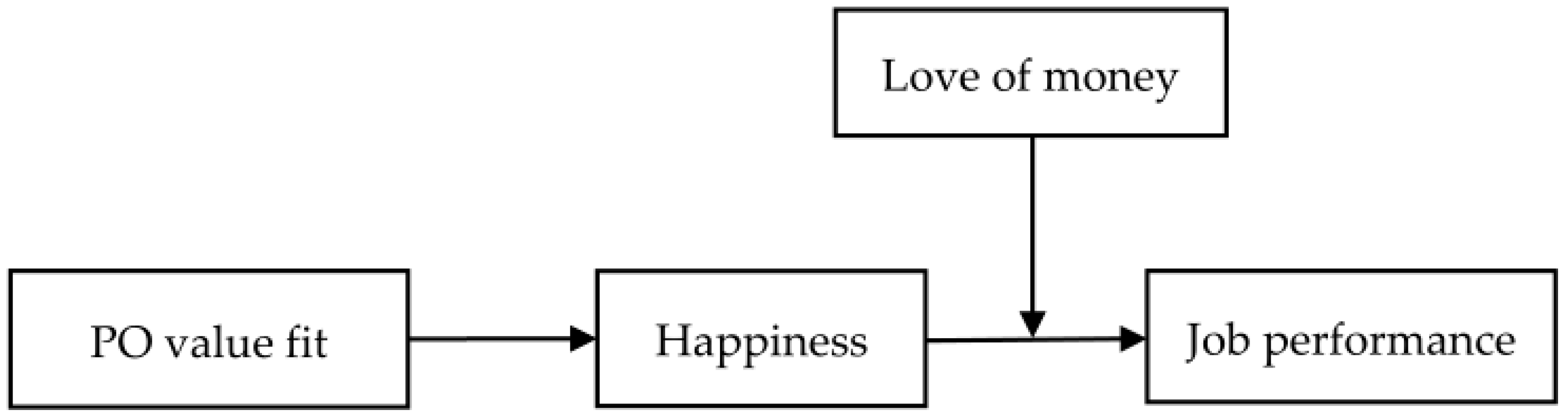

Based on the above analysis, the purposes of this study are threefold: (a) to verify the effect of PO value fit on the job performance of post-90s employees in China; (b) to test whether happiness mediates the relationship between PO value fit and job performance, and (c) to examine whether the indirect association between PO value fit and job performance via happiness is moderated by LOM. Altogether, these three objectives constitute a moderated mediation model (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The theoretical framework of this study.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling

The sample of this study was drawn from post-90s employees who were born between 1990 and 1999 and are working in a Chinese corporation. Questionnaires were issued via Sojump and the snowball method was mainly used to invite acquaintances and friends to participate in the questionnaires. Almost all walks of life participated, including building trades, the financial industry, the pharmaceutical industry, the computer industry, auto dealerships, real-estate sales, and public institutions. The anonymity, confidentiality, and use of the questionnaire for academic research purposes only were told to participants. Finally, a total of 919 participants completed all their questionnaires and passed the lie detector items (valid rate = 84%). The valid sample comprised 35% males with a mean age of 28.44 (SD = 4.86).

3.2. Measures

The conceptual model for our methodology includes four latent constructs: PO value fit, happiness, job performance, and LOM, which were measured by multiple items corresponding to previously validated scales. To ensure the accuracy of the translation procedure, translation and back-translation techniques were used. To reduce Chinese respondents’ central tendency bias [46], a 6-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree was employed for all measurement items.

For PO value fit, this study used the 3-item scale developed by Cable and DeRue to assess the value congruence between employees and their organization [13]. The items are “The things that I value in life are very similar to the things that my organization values”, “My personal values match my organization’s values and culture”, and “My organization’s values and culture provide a good fit with the things that I value in life”. To measure job performance, a job performance scale [47] consisting of a contextual performance subscale and a task performance subscale was adopted. Some examples are “I am proficient in standard operating procedures”, “Overall, I can do well with the tasks required by the company”, and “I am eager to handle difficult jobs assigned by the company”. We utilized the unidimensional, 29-item Oxford Happiness Questionnaire [48] for the measurement of happiness. The items assess energy level, optimism, perceived control of life, perceived health, social interest, perceived congruence between desired goals and actual achievements, and a general sense of happiness and life satisfaction. Some examples are “I don’t feel particularly pleased with the way I am”, “I am intensely interested in other people, social interest/extraversion”, and “I feel that life is very rewarding”. LOM was scored by a 9-item LOM scale [49] composed of three dimensions: richness, motivator, and importance. Some examples are “I want to be rich”, “I am motivated to work hard for money”, and “Money is valuable”. All these measures have a satisfactory level of internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.79 to 0.89 (shown in tables below). The demographic characteristic, age, was included as the controlled variable.

4. Results

4.1. Model Fit

First, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to ensure that the study variables constituted a good model fit. Due to the large number of items, the item-parceling technique [50] was applied. We established a measurement model including a 2-parcel job performance scale, a 3-parcel LOM scale, a 6-parcel happiness questionnaire, and a 3-item PO value fit scale, and then evaluated the model fit using Mplus8.0. A comparison of the CFA statistics for the suggested models is presented in Table 1. The results indicate that the full 4-factor model provided a more superior fit than the alternative models (χ2(71) = 397.46; RMSEA = 0.07; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.93; SRMR = 0.05).

Table 1.

CFA model fit comparison.

Additionally, the factor loading coefficients were significant at the 0.001 level, confirming the divergent validity of the current study variables. The convergent validity of the measurement items was also supported, with construct reliability (CR) ranging from 0.80 to 0.87 and average variance extracted (AVE) ranging from 0.52 to 0.70. These were both higher than the acceptance cutoff criteria of 0.7 and 0.5, respectively. Table 2 presents the standardized factor loadings, AVE, CR, and Cronbach’s α.

Table 2.

Standardized factor loadings, AVE, CR, and Cronbach’s α.

4.2. Tests of Common Method Bias

Considering that all measurement items came from a single source, the issue of common method bias is noteworthy [51]. As recommended [52], Harman’s single-factor test was carried out. The first emerging factor held a variance of 22.49%, lower than the suggested cutoff criterion of 40%. Furthermore, as Table 1 reveals, the one-factor measurement model fit denoted a poor fit (χ2(77) = 2684.72, CFI = 0.59, TLI = 0.54, and RMSEA = 0.20), confirming that the common method bias issue was likely to be eliminated.

4.3. Descriptive Statistics

The mean, standard deviation, correlation matrix, and reliability estimates are presented in Table 3. The correlation analyses showed that there are positive and significant relationships among the study variables at the 0.01 level. PO value fit was positively related to happiness and job performance (r = 0.45, p < 0.01; r = 0.49, p < 0.01, respectively). Job performance was positively related to happiness and LOM (r = 0.62, p < 0.01; r = 0.18, p < 0.01, respectively). These results identify that employees show higher job performance when they perceive higher value congruence, experience higher levels of happiness, and possess a higher level of LOM.

Table 3.

The means, standard deviations, reliability, and correlation matrix.

4.4. Mediated Effect

To examine Hypotheses 1 and 2, this study followed MacKinnon’s four-step procedure [53]. As noted below in Table 4, Step 1 shows the positive effect of PO value fit on happiness (β = 0.45, p < 0.001). In Step 2, PO value fit emerges as a significant predictor of job performance (β = 0.49, p < 0.001). In Step 3, happiness has a positive influence on job performance (β = 0.62, p < 0.001). When the indirect effect of happiness was added to the equation in Step 4, the PO value fit was still significant, and happiness remained significant (β = 0.27, p < 0.001; β = 0.50, p < 0.001, respectively). This indicates that the relationship between PO value fit and job performance was positively significant, and happiness serves as a partial mediator in this relationship. Hence, Hypotheses 1 and 2 are supported.

Table 4.

Testing the main and mediating effects of PO value fit on job performance.

4.5. Moderated Effect

The second model is the effect of LOM and happiness on job performance. To test Hypothesis 3, the hierarchical regression analysis was processed in three steps. Step 1 included only the controlled variable. Step 2 added happiness and LOM for the joint investigation. In Step 3, we created two-way interaction terms (happiness × LOM) to examine the moderating effects of LOM in relation to happiness and job performance. To alleviate collinearity-related issues caused by the interaction terms, all the variables except age were grand-mean centered [54]. This study also conducted a variance inflation factor (VIF) test for all independent, controlled, and interaction variables. All VIF values fell within an acceptable range of 1 to 1.5, indicating multicollinearity was not a serious issue.

In Step 2, all variables, including the controlled variable, were statistically significant in the positive direction (β = 0.05, p < 0.05; β = 0.62, p < 0.001; β = 0.19, p < 0.001, respectively), according to Table 5. In Step 3, the interaction between happiness and LOM was negatively related to job performance (β = −0.11, p < 0.001). The adjusted R-squared estimate increases from 0.425 in Step 2 to 0.436 in Step 3, with the changed adjusted R-squared equaling 0.011 (p < 0.01), implying that the interaction effects of happiness and LOM could impact job performance by 1.1%. These results provide evidence that LOM moderates the relationship between happiness and job performance. These patterns are consistent with Hypothesis 3, suggesting that high LOM undermines the happiness of employees, however, contributes to job performance, thereby impairing the positive impact of happiness on job performance.

Table 5.

Testing the moderated mediation effect of PO value fit on job performance.

4.6. Moderated Mediation Test

Given that the model predicting the binary outcomes did not converge, a moderated mediation test by the PROCESS program was conducted again to further examine if the mediated process was moderated by LOM. We estimated both direct and indirect effects and utilized bootstrapping procedures with 5000 resamples to place 95% confidence intervals [55]. As Table 6 illustrates, all the CIs pertaining to the direct and indirect effects of happiness were significant at all levels of LOM. For low LOM employees, PO value fit has a prominently advantageous impact on job performance through increased happiness (95% CI = [−0.26, −0.05]). However, the indirect effect of the mediated pathway was much weaker for high LOM employees (95% CI = [−0.26, −0.05]). Therefore, moderated mediation Hypothesis 3 was further supported.

Table 6.

Conditional indirect effects of PO value fit on job performance through happiness.

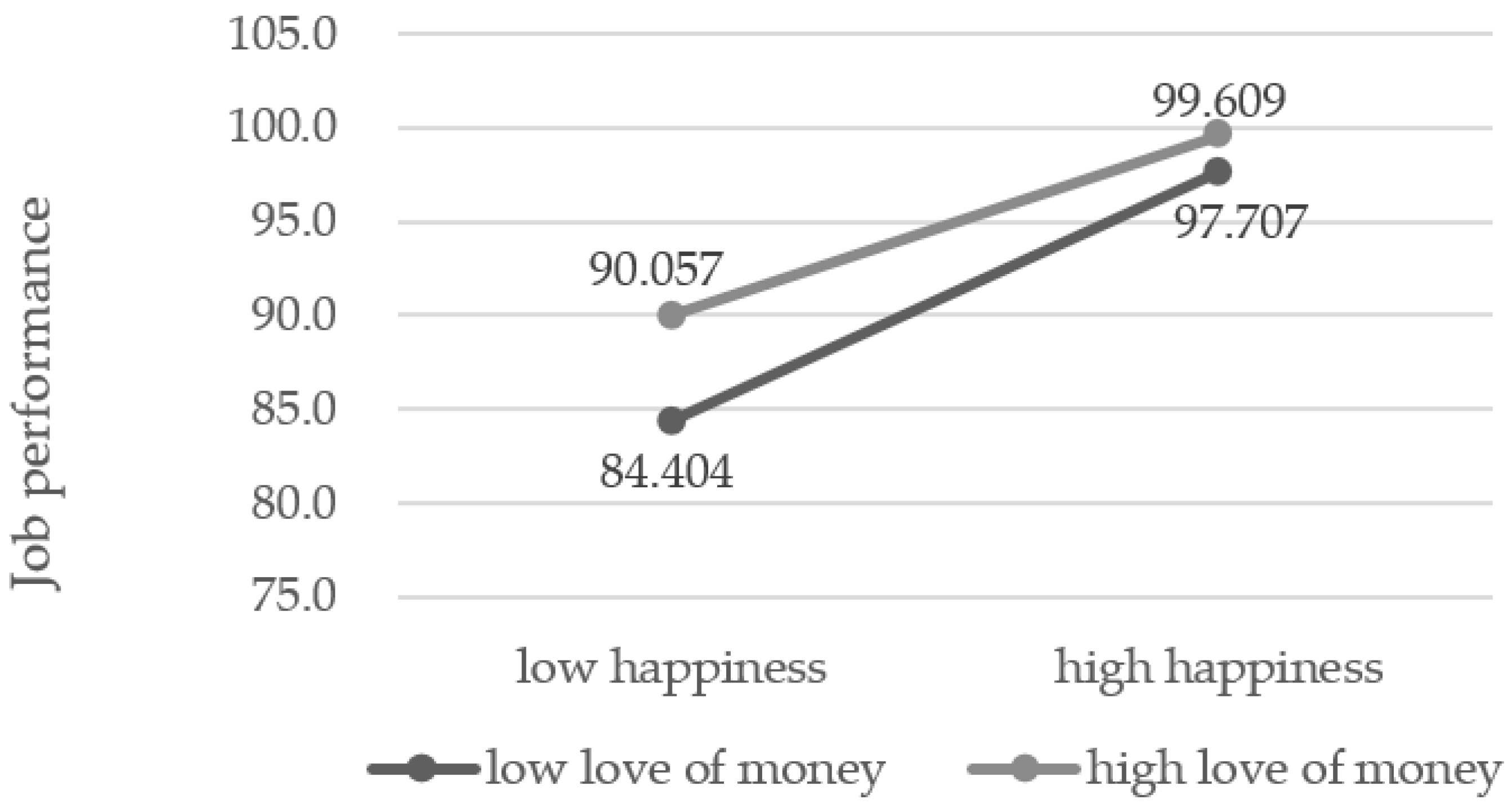

We then plotted two slopes accordingly. Following the guidance, the high and low groups based on responses one standard deviation above and below the mean [54] were distinguished. Figure 2 depicts the moderating effect of LOM on the mediation pathway by comparing the effects of LOM in two groups of low and high. As described, the slope of the LOM variable in the low group (SE = 0.026; p < 0.001) was steeper than the high group’s (SE = 0.024; p < 0.001) due to a moderating effect. This indicates that for the high LOM group, happiness only had a slight impact on job performance. In sum, all the hypotheses were supported.

Figure 2.

Interaction effects of happiness and LOM on job performance.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study is to explore the impacting mechanism of PO value fit on the job performance of post-90s employees in China. Based on the SDT, we proposed and tested a moderated mediation model in which the relationship between PO value fit and job performance is both mediated by happiness and moderated by LOM. The empirical analysis demonstrates the following.

PO value fit is a significant predictor of job performance, and this finding is consistent with previous studies [5,6]. PO value fit reflects an employee’s embedding and identification with his/her organization and can be regarded as an autonomous motivator from the perspective of SDT. It can positively influence job performance by creating an environment at the organizational level for post-90s employees to increase their three psychological needs. When PO value fit is high, the satisfaction of the three basic psychological needs of post-90s employees are more easily supported and they are more inclined to choose behaviors that are beneficial to their own or organizational development, thus showing enhanced job performance.

Happiness plays a mediating role in the relationship between PO value fit and job performance, proving that post-90s employees derive happiness when the organization supports or recognizes their values and happiness further helps organizations to promote their job performance [56,57]. This result accords with SDT, in that PO value fit is liable to build a harmonious atmosphere, which satisfies the three basic psychological needs, thereby strengthening employee autonomous motivation and increasing their happiness to achieve better job performance.

LOM lessens the significance of PO value fit in affecting job performance by diluting happiness of post-90s employees in China. This result is consistent with Diener and Biswas-Diener’s review of income and happiness, which suggests that the relationship between money and happiness is not a simple input–output relationship, but is influenced by psychological variables such as desire levels [33]. Much of the research has also detailed that an exorbitant obsession with material wealth causes individuals to undermine the sources of happiness [58,59]. Because employees who prioritize money will experience extrinsic motives [60], and these extrinsic motives may diminish basic needs satisfaction and crowd out pursuits likely to lead to greater happiness in the long term [61]. Specifically, if an employee values money highly, he may judge everything from the perspective of money, and invest more mental energy in material goals, and thus less energy is available to pursue other goals such as a happy family, close friendships, and hobbies, which are also necessary for a happy life. Despite the negative press, LOM makes an important contribution to job performance in a positive direction. This result verified that LOM could also act as an enabler or an affective, cognitive, and behavioral resource to stimulate employees to put enormous efforts into job performance [38]. This also indicates that previous research may somewhat exaggerate the negative effect of high LOM on psychological states such as self-determination and happiness while overlooking it as an important form of external motivation for job performance. Just as economists emphasized, the never-ending pursuit of material wealth is the strongest and most natural human need. Money can not only meet the basic survival needs and improve the living standards of post-90s employees but also contains a strong psychosocial meaning that can stimulate post-90s employee achievement motivation and continuously surpass themselves. The post-90s employee’s desire for and pursuit of money makes monetary rewards an important management tool.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Contributions and Implications

This study is imperative in terms of its theoretical and practical contributions. Firstly, focusing on the psychological and behavioral characteristics of post-90s employees, it helps understand the relationship between PO value fit and the job performance of post-90s employees in China. Secondly, it applies SDT to the field of organization management, expanding and extending the research perspective. Finally, it considers PO value fit as a form of autonomous motivator and LOM as a form of extrinsic motivator, and analyzes how PO value fit, happiness, LOM, and job performance interact with each other, providing a new psychological mechanism for explaining the influence of PO value fit on job performance.

The implications of this study are as follows:

To begin with, PO value fit is one of the core soft strengths for post-90s employee job performance improvement. Managers should pay attention to the fit of personal and organizational values of post-90s employees. In the staff recruitment and selection stage, greater weight could be given to those candidates with a better value fit. It is important to note, a perfect PO value fit is not necessary because PO value fit is dynamic and often changes over time [62,63]. When post-90s employees first enter an organization, they may not fit in well with the organization, but as their working years increase, they are gradually influenced by the organizational climate, thus showing characteristics that are consistent with the organization. Therefore, instead of pursuing a perfect match, organizations could pay more attention to the socialization of post-90s employees and create more opportunities to promote coherence between them and the development of the organization. Specifically, the organization could hold the corresponding cultural activities and vocational training, which can provide post-90s employees a more in-depth understanding of the organization’s goals, policies, and code of conduct. After a long period of running-in, more consistent values will naturally be formed.

In addition, low-happiness post-90s employees may focus their energy elsewhere and not be direct in their job performance efforts. Therefore, organizations should be concerned not only with their revenue but also with the happiness of post-90s employees. Satisfying the basic psychological needs of post-90s employees is highly recommended. Organizations should combine the personality characteristics of post-90s employees, provide a comfortable working environment, flexible work settings, employee fellowship, group travel, and knowledge or skill training programs, so that these employees can feel supported by the organization’s welfare policy and believe that the organization can meet their spiritual needs.

Last but not least, with reference to SDT, organizations should also realize that despite a hygiene factor or a motivation factor, monetary incentives are not the only instrument for motivating post-90s employees. The manager should not only raise the salary level to improve post-90s employee job performance, but also take their money psychology into account. In the process of personnel adjustment and recruiting, the organization can appropriately recruit those candidates with low LOM and establish the correct values and attitudes towards money of post-90s employees through culture cultivation, thus avoiding them from becoming extreme materialists or believing money is everything.

6.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study has certain limitations that need to be taken into consideration. First, causality cannot be affirmed by correlational studies. Variables in this research may have reciprocal relationships; for instance, job performance may exert an active influence on happiness as well. Therefore, other methods such as experimental investigation and lagged or longitudinal data could be used to establish the directionality in the future. Second, the self-report method was used to measure all variables, which is somewhat subjective. Different measurements can be adopted in the future. For example, job performance can be evaluated by supervisors to improve the accuracy of measurement. Third, as mentioned before, money is highly important to human life. In the workplace, managers often use money or pay to attract, retain, and motivate employees to achieve organizational goals. This study only focused on the moderating effect of subjective LOM on the relationship between PO value fit, happiness, and job performance, while ignoring the possible effect of objective pay. Future studies could further investigate respondents’ pay levels and examine whether objective pay moderates this relationship. Fourth, we focused on the role of global happiness as a mediation in the relationship between PO value fit and job performance, which may be somewhat problematic because a post-90s employee may have high global happiness despite having low PO value fit levels. As a result, future research should look into the role of job happiness, which is more closely related to the workplace, in mediating the relationship between PO value fit and job performance. Fifth, this study was conducted only with post-90s employees, which resulted in insignificant differences in age and tenure between respondents, thus failing to pay attention to the effects of age and tenure on PO value fit, happiness, LOM, and job performance. To make the findings of this study more accurate and generalizable, future studies should combine employees of other generations to further examine the effects of age and tenure.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported. Conceptualization, Y.L. and Y.H.; methodology, Y.L. and R.C.; validation, R.C.; formal analysis, Y.H.; investigation, Y.L.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, Y.L., R.C. and Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.H. and R.C.; visualization, Y.H.; supervision, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the lack of sensitive data and the anonymization of all personal information of the participants engaged in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

All questionnaires were completed voluntarily. Therefore, informed consent was obtained from all the participants involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants involved in our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Huang, J. A study on motivation strategy of new generation of post-90s employees from the perspective of self-determination theory. Mod. Biz. 2020, 14, 72–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Yu, M. Analysis of post-90s employees’ behavioral characteristics and management strategies—Based on self-determination theory perspective. Leadersh. Sci. 2019, 10, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, J.A. Improving interactional organizational research: A model of person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, I.S.; Guay, R.P.; Kim, K.; Harold, C.M.; Lee, J.H.; Heo, C.G.; Shin, K.H. Fit happens globally: A meta-analytic comparison of the relationships of person–environment fit dimensions with work attitudes and performance across east asia, europe, and north america. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 67, 99–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.K.; Yeo, S.C. Testing the relationship between person-organizational value fit and performance. Korean J. Appl. Stat. 2011, 24, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. J. Res. Pers. 1985, 19, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z.; Ying, Z.; Yahui, S.; Zhenxing, G. The different relations of extrinsic, introjected, identified regulation and intrinsic motivation on employees’ performance: Empirical studies following self-determination theory. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 2393–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.; Gagné, M.; Morin, A.J.S.; Van den Broeck, A. Motivation profiles at work: A self-determination theory approach. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 95–96, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psych. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D.M.; DeRue, D.S. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J.R.; Cable, D.M. The value of value congruence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 3, 654–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marstand, A.F.; Martin, R.; Epitropaki, O. Complementary person-supervisor fit: An investigation of supplies-values (s-v) fit, leader-member exchange (lmx) and work outcomes. Leadersh. Quart. 2017, 28, 418–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winfred, A. The use of person-organization fit in employment decision making: An assessment of its criterion-related validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 4, 786–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greguras, G.J.; Diefendorff, J.M. Different fits satisfy different needs: Linking person-environment fit to employee commitment and performance using self-determination theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 2, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hou, P. Personal-corporate values matching on employees’ work happiness. Ent. Econ. 2019, 38, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahleez, K.A.; Aboramadan, M.; Bansal, A. Servant leadership and affective commitment: The role of psychological ownership and person–organization fit. Int. J. Org. Anal. 2021, 29, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, U. Interplay between p-o fit, transformational leadership and organizational social capital. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 913–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, P.; Argyle, M. Happiness, introversion–extraversion and happy introverts. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2001, 30, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Lee, K.H.; Bae, K.H. Distinguishing motivational traits between person-organization fit and person-job fit: Testing the moderating effects of extrinsic rewards in enhancing public employee job satisfaction. Int. J. Public. Admin. 2019, 42, 1040–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 486–491. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, J.; Chang, Y.K.; Kim, T.-Y. Person–organization fit on prosocial identity: Implications on employee outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics. 2014, 123, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S. Economics of Happiness; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, W.C.; Chen, H.Y.; Chen, C.C. Incremental validity of person-organization fit over the big five personality measures. J. Psychol. 2012, 146, 485–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraç, M. Does the relationship between person–organization fit and work attitudes differ for blue-collar and white-collar employees? Manag. Res. Rev. 2017, 40, 1081–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, J.Y.; Choi, J.N. Is person–organization fit beneficial for employee creativity? Moderating roles of leader–member and team–member exchange quality. Hum. Perform. 2019, 32, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaleskiewicz, T.; Gasiorowska, A. The Psychological Meaning of Money. In The International Handbook of Consumer Psychology; Ranyard, R., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 108–122. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Tay, L.; Oishi, S. Rising income and the subjective well-being of nations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 104, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, C.J.; Brown, G.D.; Moore, S.C. Money and happiness: Rank of income, not income, affects life satisfaction. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Biswas-Diener, R. Will money increase subjective well-being? Soc. Indic. Res. 2002, 57, 119–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S.; Stutzer, A. What can economists learn from happiness research? J. Econ. Lit. 2002, 40, 402–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.P.; Chiu, R.K. Income, money ethic, pay satisfaction, commitment, and unethical behavior: Is the love of money the root of evil for hong kong employees? J. Bus. Ethics. 2003, 46, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T.; Ryan, R.M. A dark side of the american dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.L.-P.; Luna-Arocas, R.; Quintanilla Pardo, I.; Tang, T.L.N. Materialism, Love of Money, and Personal Financial Optimism in Spain; European Congress of Psychology: Istanbul, Turkey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.L.P.; Sutarso, T.; Akande, A.; Allen, M.W.; Alzubaidi, A.S.; Ansari, M.A.; Arias-Galicia, F.; Borg, M.G.; Canova, L.; Charles-Pauvers, B.; et al. The love of money and pay level satisfaction: Measurement and functional equivalence in 29 geopolitical entities around the world. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2006, 2, 423–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, S.E.; Webley, P. Money as tool, money as drug: The biological psychology of a strong incentive. Behav. Brain. Sci. 2006, 2, 161–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemrová, S.; Reiterová, E.; Fatěnová, R.; Lemr, K.; Tang, T.L.P. Money is power: Monetary intelligence—Love of money and temptation of materialism among czech university students. J. Bus. Ethics. 2014, 125, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, S.C.; Gladstone, J.J.; Stillwell, D. Money buys happiness when spending fits our personality. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 27, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockmann, H.; Delhey, J.; Welzel, C.; Yuan, H. The china puzzle: Falling happiness in a rising economy. J. Happiness. Stud. 2009, 10, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.L.P.; Luna-Arocas, R.; Pardo, I.Q.; Tang, T.L.N. Materialism and the bright and dark sides of the financial dream in spain: The positive role of money attitudes—The matthew effect. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2014, 63, 480–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsee, C.K.; Zhang, J.; Cai, C.F.; Zhang, S. Overearning. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.L.P.; Tang, D.S.H.; Luna-Arocas, R. Money profiles: The love of money, attitudes, and needs. Pers. Rev. 2005, 34, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H. Psychological contract and organizational citizenship behavior in china: Investigating generalizability and instrumentality. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 2, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decheng, Y. The Influence of Human Aspect System Factors of Quality Management on Job Performance; Institute of Business Administration, National Sun Yat-sen University: Guangzhou, China, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hills, P.; Argyle, M. The oxford happiness questionnaire: A compact scale for the measurement of psychological well-being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2002, 33, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.L.P.; Sutarso, T.; Ansari, M.A.; Lim, V.K.G.; Teo, T.S.H.; Arias-Galicia, F.; Garber, I.E.; Chiu, R.K.-K.; Charles-Pauvers, B.; Luna-Arocas, R. Monetary intelligence and behavioral economics across 32 cultures: Good apples enjoy good quality of life in good barrels. J. Bus. Ethics. 2018, 148, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chongming, Y.; Nay, S.; Hoyle, R.H. Three approaches to using lengthy ordinal scales in structural equation models: Parceling, latent scoring, and shortening scales. Appl. Psych. Meas. 2010, 34, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 5, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabati, A.A.A.; Jawad, S.N.; Bontis, N. Intellectual capital and business performance in the pharmaceutical sector of jordan. Manag. Decis. 2010, 48, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D. An introduction to statistical mediation analysis. In Apa Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 313–332. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis; Guilford Publications: Guilford, NC, USA, 2013; pp. 335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, C. Erratum: Employee well-being in organizations: Theoretical model, scale development, and cross-cultural validation. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Garrido, J.A.; Biedma-Ferrer, J.M.; Ramos-Rodríguez, A.R. Relationship between work-family balance, employee well-being and job performance. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. AD. 2017, 30, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helga, D. The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 5, 879–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitchai, N.; Senasu, K.; Sakworawich, A. The moderating effect of love of money on relationship between socioeconomic status and happiness. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 41, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, J.E. Subjective Well-Being and Life Satisfaction; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kasser, T. The High Price of Materialism; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vleugels, W.; Tierens, H.; Billsberry, J.; Verbruggen, M.; De Cooman, R. Profiles of fit and misfit: A repeated weekly measures study of perceived value congruence. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swider, B.W.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Barrick, M.R. Searching for the right fit: Development of applicant person-organization fit perceptions during the recruitment process. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 3, 880–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).