Protection System and Preservation Status for Heritage of Industrial Modernization in China—Based on a Case Study of Shenyang City

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

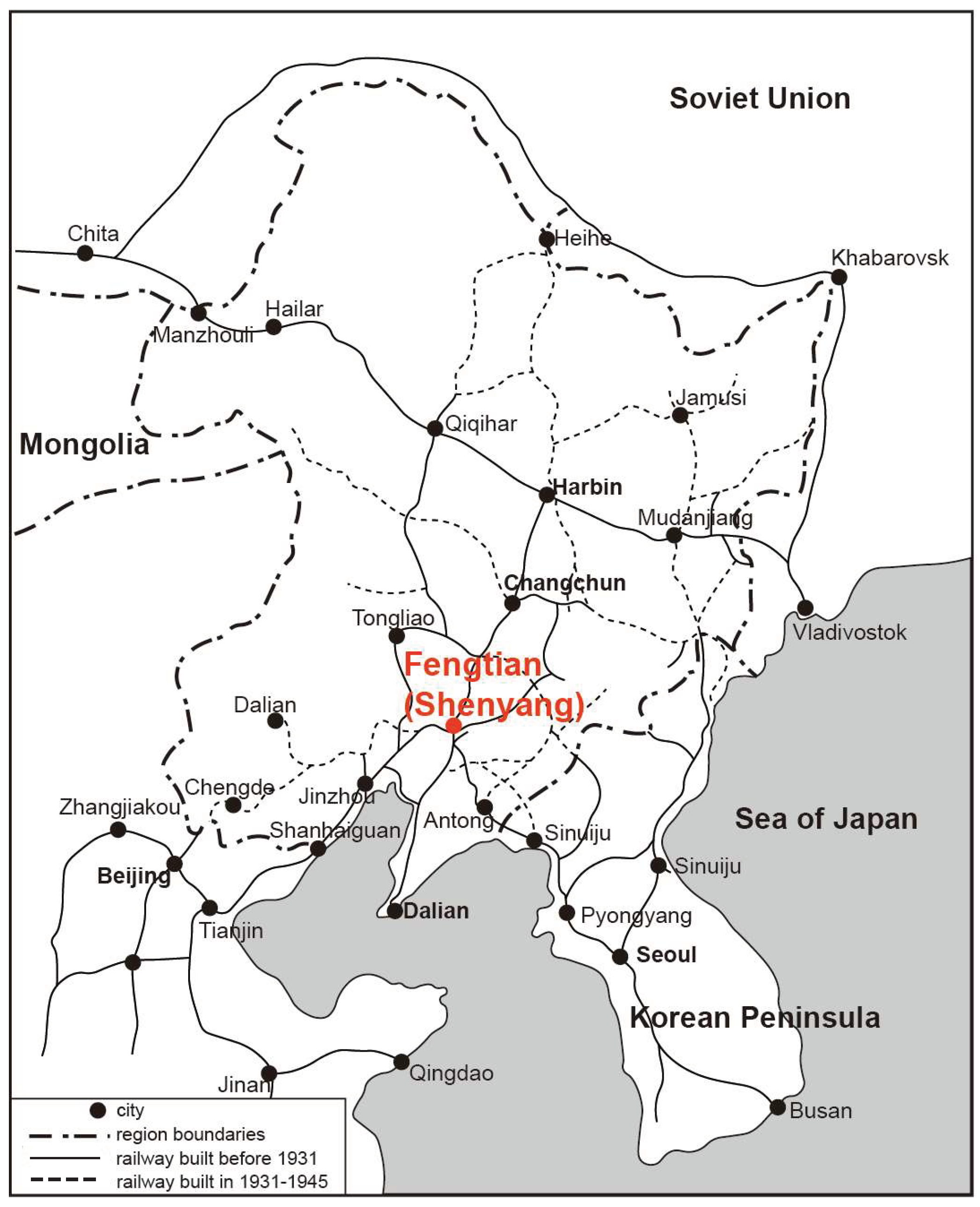

1.2. Modern Development and HOIM in Shenyang

1.3. Literature Review

1.4. Materials and Methods

2. Protection System Related to the HOIM in China

2.1. Protection System at the National Level

2.1.1. Position of HOIM in the System of Cultural Relics Protection Law

2.1.2. Position of the HOIM in the Historical and Cultural Cities Protection Regulation

2.2. Protection System in Shenyang

3. Changes in the Utilization Status and the Factors Applying to the Openness of HOIM

3.1. Changes in the Utilization Status of HOIM in Shenyang

3.1.1. Changes in the Identification of Historical and Cultural Sites Protected

3.1.2. Changes in Types of HOIM Facility Users

3.1.3. Changes in the Composition in Facility Use Classification

3.2. Openness and Influencing Factors of the HOIM

3.2.1. Openness of HOIM Facilities and Their Criteria

3.2.2. The Relationship between Influencing Factors and the Openness of HOIM Facilities

4. Discussion and Results

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hudson, K. Industrial Archaeology: An Introduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-315-74638-8. [Google Scholar]

- Namikawa, H. About Industrial Archaeology and Industrial Heritage. St. Univ. Bull. Res. Inst. 2014, 40, 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Twentieth-Century Architectural Heritage: Strategies for Conservation and Promotion: Proceedings; Council of Europe Press: Strasbourg, France, 1994; ISBN 978-92-871-2463-0. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Headquarters. Report of the Expert Meeting on the “Global Strategy” and Thematic Studies for a Representative World Heritage List 1994. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/1570 (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Inoue, S. Industrial Archaeology and Industrial Heritage: What Is the Purpose of Collecting Information and Who Should We Preserve It For? St. Univ. Bull. Res. Inst. 2004, 30, 61–90. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, X. An International Interpretation of the Ideology of Built Heritage Conservation in Modern China. Arch. J. 2009, 6, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, F.; Murumatsu, S.; Nishizawa, Y. The Architectural Heritage of Modern China: The Shenyang Chapter; China Architecture Publishing & Media Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 1995; ISBN 978-7-112-02608-1. [Google Scholar]

- Jouji, S. Problems of Preservation and Utilization on Industrial Heritages. Proc. Gen. Meet. Assoc. Jpn. Geogr. 2011, 2011, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. Sweetened Imposition: Re-Examining the Dilemma of the Adaptive Re-Use of Former Sugar Factory Sites as Cultural Creative Parks in Taiwan. Int. J. Cult. Creat. Ind. 2015, 2, 68–83. [Google Scholar]

- Toma, T. Battlefield Archaeology in Okinawa. In Proceedings of the 1st the Japanese Disaster Prevention and Archaeology Association, Miyagi, Japan, 22 September 2022; pp. 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K. The Industrial Heritage: Historical Vayage through the Life of the Everyday Man; Nikkei Inc.: Tokyo, Japan, 1999; ISBN 978-4-532-14676-4. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Aerial View of the Hashima Coal Mine 2010. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/136176/ (accessed on 17 December 2022).

- UNESCO. Former Kagoshima Foreign Engineer’s Residence 2012. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/136169 (accessed on 17 December 2022).

- Masato, H.; Kiyoko, T.; Takeshi, O. Reports on Preservation and Utilization of the Modernization Heritage in Yokohama. Nara Prefect. Univ. Kenkyukiho 2014, 25, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y. The Protection and Regeneration of Urban Industrial Cultural Heritage under the “Industrial Park Model”: The Case of Beijing 798 Art Park. Chongqing Archit. 2022, 21, 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y. Exploration on the Conservation and Renewal Methods of Atypical Historic Districts from the Perspective of HUL—Taking Shanghai Tianzifang as an Example. Inter. Archit. China 2022, 11, 150–152. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, N. Brief Analysis of the Influence of Opening Trading Port on the Development of Industry and Commerce in Modern Mukden(1906–1931). Lit. Life (Trimonthly Publ.) 2016, 1, 155–156. [Google Scholar]

- Su, C. History of the Mantetsu; Fourteen Years of the Fall of Northeast China Series; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1990; ISBN 978-7-101-00844-9. [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa, Y. Illustrated Manchuria: Giant of Manchuria; Kawade Shobo Shinsha: Tokyo, Japan, 2015; ISBN 978-4-309-76232-6. [Google Scholar]

- Keiichi, Y. Urban Planning Characteristics of Shinkei, Hoten, and Harbin. Research bulletin of Meisei University. Phys. Sci. Eng. 1971, 6, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, S. The South Manchuria Railway Co., Ltd. Complete History: The Total Picture of The Semi-Governmental Corporation; Kodansha Gakujutsu Bunko: Tokyo, Japan, 2006; ISBN 978-4-06-516272-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mukden City Public Works Department, Urban Planning Division. Planning Map of Fengtian Capital City Project [Map]; Urban Planning Division of Mukden Government: Shenyang, China, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- The South Manchuria Railway Co., Ltd. South Manchuria Railway Travel Guide; The South Manchuria Railway Co., Ltd.: Dalian, China, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. World Heritage Centre Map Showing the Imperial Palace in Beijing. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/439/documents/ (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Bureau of Land and Resources of Shenyang City. List of Protected Historical and Cultural Sites in Shenyang 2020. Available online: http://www.shenyang.gov.cn/. (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Ye, P. The Speed of Cultural Preservation Can Not Catch Up with The Urbanization Nearly 400 Historical Buildings Disappeared in 23 Years in Shenyang. Workers’ Daily. 14 December 2015. Available online: https://www.chinanews.com.cn/sh/2015/12-14/7669413.shtml (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- He, Y. Shenyang National Site Protected Unmanaged, Shuaifu Office Into A Dangerous Building. People’s Daily. 17 November 2011. Available online: https://www.chinanews.com.cn/gn/2011/11-17/3466279.shtml (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Lu, L. The Mantetsu Library Forced to Move. Res. Mantetsu 2009, 1, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, E. Survey and Preservation on Modernization Heritage. J. Archit. Build. Sci. 1991, 1991, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. 33 Heritage Constellations of Industrial Modernization 2007. Available online: https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/mono_info_service/mono/creative/kindaikasangyoisan/index.html. (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Lan, W.; Hu, M.; Zhao, Z. Review, Characteristics and Prospects of the Protection System of Historic Cities. Urban Plan. Forum 2019, 2, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamashita, T. Historical Transformation of Coastal Urban City Networks in East China Sea Zone: From Pusan-Nagasaki-Ryukyu-Southeast Asia Channel to Yinchon-Shanghai-Kobe Channel. J. Soc. Sci. 2009, 60, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskell, L. Negative Heritage and Past Mastering in Archaeology. Anthropol. Q. 2002, 75, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. The Japanese Colonial Empire and Its Industrial Legacy. In Proceedings of the Selected Papers of the XVth International Congress of the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage, Taipei, Taiwan, 4–8 September 2012; pp. 208–218. [Google Scholar]

- Moropoulou, A.; Lampropoulos, K.; Apostolopoulou, M.; Tsilimantou, E. Novel, Sustainable Preservation of Modern and Historic Buildings and Infrastructure. The Paradigm of the Holy Aedicule’s Rehabilitation. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2021, 15, 864–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Jia, B. Discussion on Applying Trombe Wall Technology for Wall Conservation and Energy Saving in Modern Historic Buildings. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2019, 13, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, J. Heritage Conservation Future: Where We Stand, Challenges Ahead, and a Paradigm Shift. Global Chall. 2022, 6, 2100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, C.; Sutherland, M. Built Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Urban Development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Munday, M. Blaenavon and United Nations World Heritage Site Status: Is Conservation of Industrial Heritage a Road to Local Economic Development? Reg. Stud. 2001, 35, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orange, H. Industrial Archaeology: Its Place Within the Academic Discipline, the Public Realm and the Heritage Industry. Ind. Archaeol. Rev. 2008, 30, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicke, C.; Berger, S.; Golombek, J. Industrial Heritage and Regional Identities; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxford, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-0-367-59236-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rieko, S.; Katsuhiro, K.; Naoaki, O. Study on Variety of Pedestrian Space with Conversion of the Historical Buildings in Area Surrounding Otaru Canal. Urban Plan. Build. Econ. Hous. Issues 2007, 2007, 309–310. [Google Scholar]

- Rieko, S.; Katsuhiro, K. Basic Study on Realities of Conversion of Historical Buildings of Local City in Hokkaido. J. City Plan. Inst. Jpn. 2010, 45, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumi, F.; Hirokazu, A.; Tomoko, H. A Primary Contractor’s Role in Conservation of Industrial Heritage: Cases of Textile Mill in Osaka and Hyogo. J. Archit. Plan. Trans. AIJ 2013, 78, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Xu, S.; Aoki, N.; Tian, T. The Activities of Architectural Organizations and Technicians Under Colonial Rule—Take the Construction of Anshan Steel Works and Anshan Urbanization under Japanese Colonial Rule as an Example. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Tong, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Hu, L. Value Analysis and Rehabilitation Strategies for the Former Qingdao Exchange Building—A Case Study of a Typical Modern Architectural Heritage in the Early 20th Century in China. Buildings 2022, 12, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, Y. Japanese Colonial Architecture; The University of Nagoya Press: Nagoya, Japan, 2008; ISBN 978-4-8158-0580-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Urban Study of Modern Shanghai; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1990; ISBN 978-7-5321-3275-1. [Google Scholar]

- Yuzo, Y. (Ed.) Research on Manchukuo; Ryokage Shobo Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 1995; ISBN 978-4-89774-547-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, L.; Mikiko, I. A Historical Study on the Evolution of Parks, Open Space and Park System Planning in Shenyang City, China- from the End of the 19th Century to 1945. J. City Plan. Inst. Jpn. 2010, 45, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B. Study on the Spatial Evolution of Historical and Cultural Forms in Modern Shenyang. Master’ Thesis, Shenyang Jianzhu University, Shenyang, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L. The Modernization Process of The City and Architecture of The Manchurian Railway Annex in Modern Shenyang. Archit. Cult. 2013, 10, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Guo, J. A Historical Study of Urban Planning Paradigms in Japanese-Occupied Areas of Modern China. Urban Plan. J. 2003, 4, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Cenci, J.; Becue, V.; Koutra, S.; Liao, C. Stewardship of Industrial Heritage Protection in Typical Western European and Chinese Regions: Values and Dilemmas. Land 2022, 11, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. Study on the Implementation Path of Overall Conservation and Reuse of Industrial Heritage. Master’ Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. Research on the Protection and Regeneration of Industrial Building Heritage along the Canal in Hangzhou. Master’ Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Sustainable Development and Comparison between Three Provinces of Northeast China and Ruhr Germany from the Perspective of Industrial Tourism. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Seminar on Education, Management and Social Sciences (ISEMSS 2022), Dali, China, 15–17 July 2022; pp. 2082–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Shenyang Residence of Warlord Called Feng Faction’s Conservation and Reuse Research. Master’ Thesis, Shenyang Jianzhu University, Shenyang, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Shi, H.; Peng, L.; Song, M. Research of Combination Urban Culture Landscape With Time-Honored Brand Culture Regeneration—In Case of Time-Honored Brand Enterprise in Shenyang Catering Industry. J. Hum. Settl. West China 2016, 31, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Research on the Law System of China’s Historical Cities Protection. Master’ Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Research on the System of Officially Protected Site in China. Doctoral’ Thesis, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, D. A Study on Identification Criteria of Excellent Modern Architectures. Master’ Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Deng, K. A Study on the Changes of Regulations Related to the Conservation and Utilization of Landscape Heritage in Shenyang. In Proceedings of the 2019 Annual Conference of the Chinese Society of Landscape Architecture (Previous), Shanghai, China, 18–21 October 2019; pp. 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, D. Preservation and Heritage of Shenyang’s Historic Urban Landscape. Master’ Thesis, Shenyang Jianzhu University, Shenyang, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Fu, C.; Liu, X.; Xie, B.; Zhang, P. Study on the Conservation and Redesign of Shenyang’s Historic Urban Landscape. ChengShi Jianshe LiLun Yan Jiu 2014, 19, 786. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. A Way to Improve the Quality of Historical and Traditional Districts in the Construction of Shenyang’s Famous Historical and Cultural City. Cult. Ind. 2022, 1, 124–126. [Google Scholar]

- Mısırlısoy, D.; Günçe, K. Adaptive Reuse Strategies for Heritage Buildings: A Holistic Approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhojaly, R.A.; Alawad, A.A.; Ghabra, N.A. A Proposed Model of Assessing the Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Buildings in Historic Jeddah. Buildings 2022, 12, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Ali, Z.; Zawawi, R.; Myeda, N.E.; Mohamad, N. Adaptive Reuse of Historical Buildings: Service Quality Measurement of Kuala Lumpur Museums. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2018, 37, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadzadehyazdi, S.; Ansari, M.; Mahdavinejad, M.; Bemaninan, M. Significance of Authenticity: Learning from Best Practice of Adaptive Reuse in the Industrial Heritage of Iran. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2020, 14, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chiu, Y.; Tsai, L. Evaluating the Adaptive Reuse of Historic Buildings through Multicriteria Decision-Making. Habitat Int. 2018, 81, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandru, I.; Grama, V. The External Western Balkan Border of the European Union and Its Borderland: Premises for Building Functional Transborder Territorial Systems. Ann. Istrian Mediterr. Stud. 2010, 20, 457–468. [Google Scholar]

- Meulman, J.J. Prediction and Classification in Nonlinear Data Analysis: Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed, Something Blue. Psychometrika 2003, 68, 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Pujari, V. Exploring Usage of Mobile Banking Apps in the UAE: A Categorical Regression Analysis. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2022, 27, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabareseh, S. Can Business-to-Consumer Electronic Commerce Be a Game-Changer in Anglophone West African Countries? Insights from Secondary Data and Consumers’ Perspectives. World Appl. Sci. J. 2014, 30, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çilan, Ç.A.; Can, M. Measuring Factors Effecting MBA Students’ Academic Performance by Using Categorical Regression Analysis: A Case Study of Institution of Business Economics, Istanbul University. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 122, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China Notice on the Approval and Publication of the Eighth Batch of Historical and Cultural Sites Protected on the National Level. Gaz. State Counc. People’s Repub. China 2019, 1677, 9–37.

- Shenyang Planning and Land Resources Bureau. Master Plan of Shenyang City (2011–2020), Chapter 8: The Conservation Planning of Historical City 2016. Available online: http://m.planning.org.cn/zx_news/4958.htm (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Nishizawa, Y. Illustrated Tales of “Manchurian” Cities: Harbin, Dalian, Shenyang, and Changchun; Kawade Shobo Shinsha: Tokyo, Japan, 1996; ISBN 4-309-72558-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, B. Historical Study of Modern Urban Planning in Shenyang; Shandong People’s Publishing House: Jinan, China, 2017; ISBN 978-7-209-10937-6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Liu, S.; Shen, X.; Ha, J. History of Modern Architecture in Shenyang; China Architecture& Building Press: Beijing, China, 2016; ISBN 978-7-112-18540-5. [Google Scholar]

- Local Chronicles Office of Shenyang Municipal People’s Government. Shenyang City Annals Volume 2: Urban Construction; Shenyang Publishing House: Shenyang, China, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B. Shenyang City Architecture Illustration; China Machine Press: Beijing, China, 2011; ISBN 978-7-111-31262-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. Shenyang Historical Sites Illustration; Shenyang Publishing House: Shenyang, China, 2002; ISBN 978-7-1113-1262-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B. Inventory of Historical Buildings in Shenyang City; Southeast University Press: Nanjing, China, 2010; ISBN 978-7-5641-2081-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ilieș, D.C.; Hodor, N.; Indrie, L.; Dejeu, P.; Ilieș, A.; Albu, A.; Caciora, T.; Ilieș, M.; Barbu-Tudoran, L.; Grama, V. Investigations of the Surface of Heritage Objects and Green Bioremediation: Case Study of Artefacts from Maramureş, Romania. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. Landscape of Mukden City: Inheriting a Thousand Years of Culture. Shenyang’s Daily. 14 October 2010. Available online: https://h.r.sn.cn/M3mzZS (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Sasaki, K.; Matsumoto, S. Status of Actual Introduction and Operation of Designated Manager System in Tokyo Metropolitan City Parks. J. Environ. Inf. Sci. 2022, 36, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakasa, T.; Muraki, M. A Study on PFI Projects by the Local Authority. J. City Plan. Inst. Jpn. 2005, 40, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenyang Planning and Land Resources Bureau Searching for the Imprint of Urban Space: Re-Call for Clues of Old Buildings in Shenyang. Available online: http://zrzyj.shenyang.gov.cn/ztgz/lswhmcbh/202208/t20220822_4107441.html (accessed on 6 January 2023).

| Law and Regulation | Contents of Protection System | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National level | Cultural Relics Protection Law; Historical and Cultural Cities Protection Regulation | The City/Urban Layer | The Area Layer | The Individual Structure Layer |

| Historical and Cultural Cities | Historical and Cultural Towns, Villages and Blocks (Areas) | Historical Buildings * | ||

| Shenyang City level | Regulations on Protecting Historical and Cultural City of Shenyang; Scheme on Historical Buildings Identification of Shenyang | Historic Urban Area | Historical and Cultural Blocks | Historical Buildings |

| Mukden City; South Manchuria Railway Zone; Treaty Port Area | Fangcheng Historical and Cultural Block; Shenyang Station–Zhongshan Road—Zhongshan Square Block; Tiexi Worker’s Village Historical and Cultural Block | Buildings and structures that can reflect the historical appearance and local characteristics of Shenyang, but are not registered as Protected Historical and Cultural Sites or Immovable Cultural Relics, the certification of Class 1, 2 and 3 Historical Buildings can be granted based on their historical, cultural value | ||

| Method | Content and Details | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Maintaining the Original Condition | The principle of keeping the Immovable Cultural Relics in their original state shall be adhered to in their use and other operations. | Cultural Relics Protection Law, Article 21 and 26. |

| Besides Immovable Cultural Relics, the principle above is also applied to Class 1 historic buildings. | Scheme on Historical Buildings Identification of Shenyang, Article 11. | |

| 2. On-site Preservation | It shall do everything it can to protect the original site protected for its historical and cultural value. | Cultural Relics Protection Law, Article 20; |

| Where historical buildings cannot be protected on their original sites and must be moved to another place for protection or demolished, the administrative department of the people’s government shall report to the administrative department of cultural relics at the next higher level for approval. | Historical and Cultural Cities Protection Regulation, Article 34. | |

| 3. “The Four Principles “ (This is the abbreviated term of Cultural Relics Protection Law, Article 15) * | For preserving Protected Historical and Cultural Sites, the principles that ① delimiting a necessary area, ② putting up signs and notes, ③ establishing records and files, and ④ establishing special organs or assigning full-time persons to be responsible for control over these sites, shall be observed. | Cultural Relics Protection Law, Article 15; Historical and Cultural Cities Protection Regulation, Article 32. |

| We shall stipulate the detailed preservation area and the restricted construction activities within the scope. | Regulations on protecting Historical and Cultural City of Shenyang, Article 18 and 22 | |

| 4. Establishing A Conservation Planning of Historical Urban Space | A detailed consecration plan shall be established by the local people’s government in a year, since a historical and cultural city (town, village, or area) has been verified and announced. | Cultural Cities Protection Regulation, Article 13 |

| The specific contents of the preservation plan shall be appointed. | Regulations on protecting Historical and Cultural City of Shenyang, Article 9 to 11 | |

| 5. Restrictions in utilization and Renovation | Where it is necessary to use a building verified as a protected historical and cultural site, other than the establishment of a museum, a cultural relics preservation institute, or a tourist site, the administrator of this site shall report to the department for cultural relics of government for approval. | Cultural Relics Protection Law, Article 23 to 26; Historical and Cultural Cities Protection Regulation, Article 35. |

| For class 2 historical buildings, the exterior shape, finish materials and colors, important internal structure, and important decoration shall not be altered, while the internal non-important structure and decoration may make changes. For class 3 historical buildings, it is allowed for changes in the structure and decoration of the interior of the building without undermining the conservation value or altering the exterior form, color, and important finishing materials of the building. | Scheme on Historical Buildings Identification of Shenyang, Article 11. |

| Announcement Time | The Quantity for Historical and Cultural Sites Protected | The Quantity for HOIM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Breakdown in Levels | Total | Breakdown in Levels | |||||

| National Level | Provincial Level | City Level | National Level | Provincial Level | City Level | |||

| 1961 | 1 | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1963 | 4 | − | 4 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1979 | 1 | − | 1 | − | 1 | − | 1 | − |

| 1982 | 1 | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1985 | 8 | − | 8 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1988 | 5 | 1 | 4 | − | 1 | − | 1 | − |

| 1996 | 9 | 1 | 8 | − | 5 | 5 | − | − |

| 2001 | 3 | 3 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2003 | 10 | − | 10 | − | 5 | − | 5 | − |

| 2006 | 3 | 3 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2007 | 2 | − | 2 | − | 1 | − | 1 | − |

| 2008 | 47 | − | 3 | 44 | 28 | − | − | 28 |

| 2013 | 67 | 7 | − | 60 | 34 | 16 | − | 18 |

| 2014 | 29 | − | 29 | − | 25 | − | 25 | − |

| 2018 | 15 | − | 15 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2019 | 4 | 4 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2020 | 29 | − | − | 29 | 8 | − | − | 8 |

| Total | 238 | 21 | 84 | 133 | 108 | 21 | 33 | 54 |

| Current Use | Original Use | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative | Educational | Commercial | Industrial and Transportation | Cultural and Welfare | Business | Residence | Total | |

| Administrative | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 12 | 24 |

| Educational | 1 | 18 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Commercial | 2 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 20 |

| Industrial and Transportation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Cultural and Welfare | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 4 | 10 | 37 |

| Business | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 3 | 18 |

| Vacancy | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 9 |

| Total | 16 | 22 | 8 | 9 | 19 | 27 | 31 | 132 |

| VARIABLE | SCALING LEVEL | CATEGORY |

|---|---|---|

| Openness | Ordinal | Level 1–5 |

| Type of Facility Use Conversion | Nominal | Continued Original Use; Administrative Facility Conversion; Cultural Facility Conversion; Commercial Facility Conversion; Unused; Others. |

| Type of Users | Nominal | Private Use; Government Administration; Foreign-owned Enterprises; Civil Society Organizations; Private Enterprise; State-owned General Enterprises; State-owned Public Utilities; Others. |

| Level of Historical and Cultural Sites Protected | Ordinal | National Level; Provincial Level; City Level; No Level. |

| Site Conditions with Conservation Areas | Nominal | Mukden City; South Manchuria Railway Zone; Treaty Port Area; Others. |

| Site Conditions with Conservation Blocks | Nominal | Inner; Outer. |

| Multiple R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.79 | 0.624 | 0.567 | 0 |

| Beta | Tolerance | Importance | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After Transformation | Before Transformation | ||||

| Type of Facility Use Conversion | 0.584 | 0.92 | 0.658 | 0.633 | 0 |

| Type of Users | 0.316 | 0.913 | 0.715 | 0.21 | 0 |

| Level of Historical and Cultural Sites Protected | 0.143 | 0.872 | 0.823 | 0.037 | 0.018 |

| Site Conditions with Conservation Areas | 0.156 | 0.856 | 0.644 | 0.059 | 0.005 |

| Site Conditions with Conservation Blocks | 0.11 | 0.778 | 0.546 | 0.061 | 0.185 |

| TYPE OF USERS | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State-owned Public Utilities | State-owned General Enterprises | Private Enterprise | Civil Society Organizations | Foreign-owned Enterprises | Government Administration | Others | |||

| TYPE OF FACILITY USE CONVERSION | Continued Original Use | 31 | 7 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 62 |

| Cultural Facility Conversion | 19 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 23 | |

| Commercial Facility Conversion | 4 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | |

| Unused | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 9 | |

| Others | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | |

| Administrative Facility Conversion | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 19 | |

| Total | 60 | 11 | 20 | 5 | 2 | 24 | 10 | 132 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, B.; Ikebe, K.; Han, Y.; He, X. Protection System and Preservation Status for Heritage of Industrial Modernization in China—Based on a Case Study of Shenyang City. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031984

Sun B, Ikebe K, Han Y, He X. Protection System and Preservation Status for Heritage of Industrial Modernization in China—Based on a Case Study of Shenyang City. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031984

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Bingyu, Konomi Ikebe, Yirui Han, and Xiangting He. 2023. "Protection System and Preservation Status for Heritage of Industrial Modernization in China—Based on a Case Study of Shenyang City" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031984

APA StyleSun, B., Ikebe, K., Han, Y., & He, X. (2023). Protection System and Preservation Status for Heritage of Industrial Modernization in China—Based on a Case Study of Shenyang City. Sustainability, 15(3), 1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031984