Sustainability and Organizational Performance in South Korea: The Effect of Digital Leadership on Digital Culture and Employees’ Digital Capabilities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

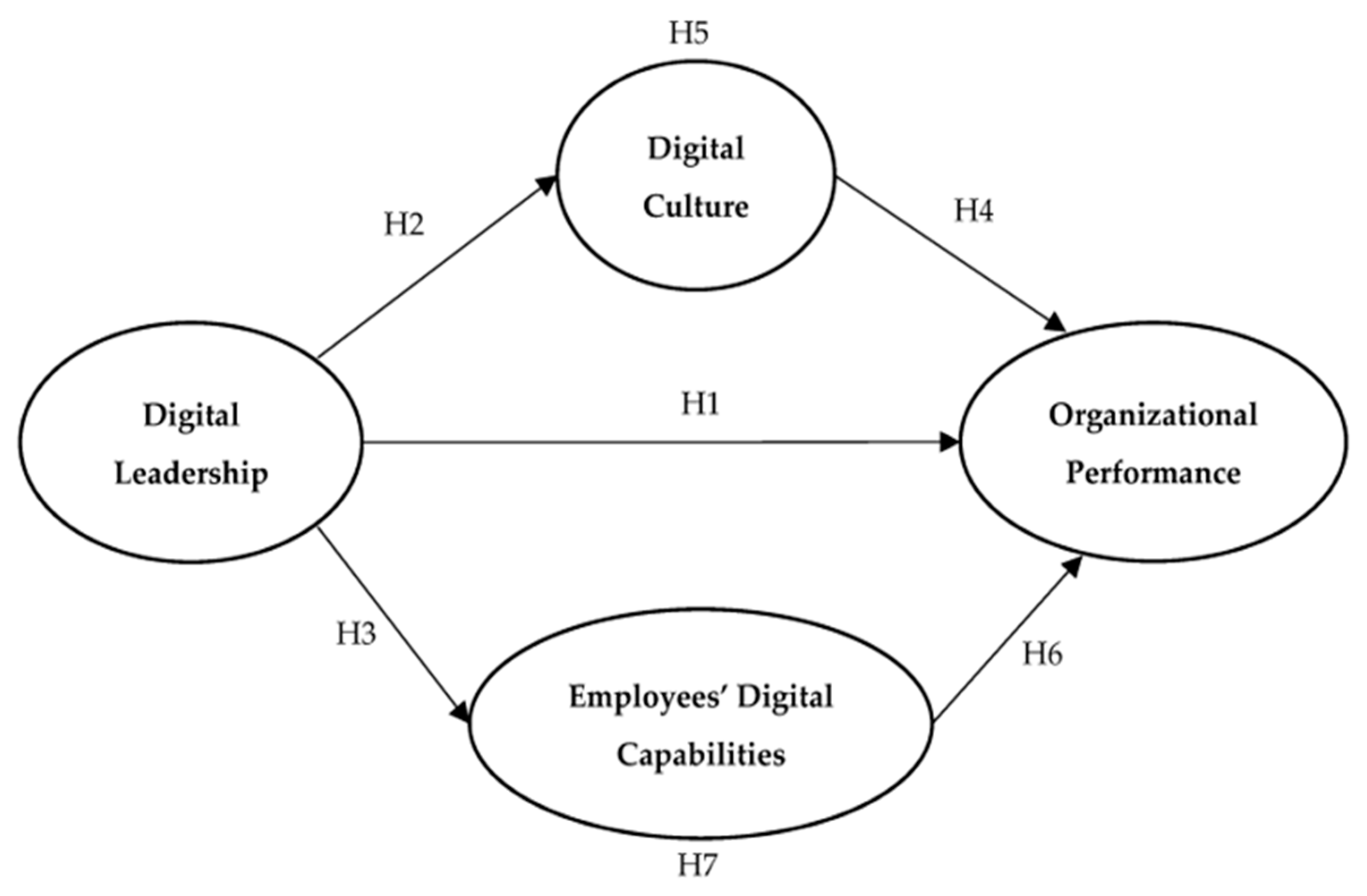

- RQ1: What is the effect of digital leadership on organizational performance for sustainability in South Korea?

- RQ2: What are the roles of digital culture in DL and performance for organizational sustainability?

- RQ3: What is the role of employees’ digital capabilities in the relationship between DL and performance for organizational sustainability?

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. The Effect of Digital Leadership on Organizational Performance

2.2. The Effect of Digital Leadership on Digital Culture and Employees’ Digital Capabilities

2.3. The Role of Digital Culture

2.4. The Mediating Role of Employees’ Digital Capabilities

3. Research Model and Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement of Variables

3.3. Construct Validity Analysis

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Structural Model

4.2. Testing of the Hypotheses

5. Conclusions and Discussions

5.1. General Discussion

5.2. Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| 1. Digital Leadership: Please rate whether the following statements apply to your company on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). |

| DL1: A digital leader raises the awareness of the employees of the institution about the risks of information technologies. |

| DL2: A digital leader raises awareness of the technologies that can be used to improve organizational processes. |

| DL3: A digital leader determines the ethical behaviors required for informatics practices together with all its stakeholders. |

| DL4: A digital leader plays an informative role to reduce resistance to innovations brought by information technologies. |

| DL5: A digital leader shares his/her own experiences about technological possibilities that help his/her colleagues to learn about the organization’s structure. |

| DL6: In order to increase participation in the corporate vision, a digital leader guides the employees of the institution regarding the technological tools that can be used. |

| 2. Employees’ Digital Capabilities: Please rate whether the following statements apply to your company on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). |

| EDC1: We offer different training (courses, literature, coaching) to improve the digital expertise of our team members. |

| EDC2: Digital skills are an important selection criterion in recruiting new team members. |

| EDC3: Our team members use all digital services and products we offer. |

| EDC4: Our team has the necessary skills to further digitalize our company. |

| EDC5: We actively discuss our digital projects within our company, including failures and best practices. |

| 3. Digital Culture: Please rate whether the following statements apply to your company on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). |

| DC1: We openly discuss failures with all team members. |

| DC2: Decisions are based on the opinion of the whole team, not on a single person only. |

| DC3: We work in cross-functional teams (combining people from IT, marketing, finance, etc.). |

| DC4: In our company, we avoid strong hierarchies in project work. |

| DC5: Every team member brings in ideas and suggestions for digital products and services. |

| 4. Organizational Performance: Please rate whether the following statements apply to your company on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). |

| OP1: Compared with key competitors, our company is more successful. |

| OP2: Compared with key competitors, our company has a greater market share. |

| OP3: Compared with key competitors, our company is growing faster. |

| OP4: Compared with key competitors, our company is more profitable. |

| OP5: Compared with key competitors, our company is more innovative. |

References

- Holzmann, P.; Schwarz, E.J.; Audretsch, D.B. Understanding the Determinants of Novel Technology Adoption among Teachers: The Case of 3D Printing. J. Technol. Transf. 2020, 45, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wesseling, J.H.; Bidmon, C.; Bohnsack, R. Business Model Design Spaces in Socio-Technical Transitions: The Case of Electric Driving in the Netherlands. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 154, 119950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B. Digital Leadership: State Governance in the Era of Digital Technology. Cult. Sci. 2021, 5, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalaldin, A.; Linde, L.; Sjödin, D.; Parida, V. Transforming Provider-Customer Relationships in Digital Servitization: A Relational View on Digitalization. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araujo, L.M.; Priadana, S.; Paramarta, V.; Sunarsi, D. Digital Leadership in Business Organizations: An Overview. Int. J. Educ. Adm. Manag. Leadersh. 2021, 2, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihardjo, L.W.W.; Sasmoko, S.; Mihardjo, L.W.W.; Sasmoko, S. Digital Transformation: Digital Leadership Role in Developing Business Model Innovation Mediated by Co-Creation Strategy for Telecommunication Incumbent Firms; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amelda, B.; Alamsjah, F.; Elidjen, E. Does The Digital Marketing Capability of Indonesian Banks Align with Digital Leadership and Technology Capabilities on Company Performance? Commun. Inf. Technol. J. 2021, 15, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waal, A.; Heijtel, I. Searching for Effective Change Interventions for the Transformation into a High Performance Organization. Manag. Res. Rev. 2016, 39, 1080–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarros, J.C.; Cooper, B.K.; Santora, J.C. Leadership Vision, Organizational Culture, and Support for Innovation in Not-for-profit and For-profit Organizations. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2011, 32, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadisen, M.S.A.; Salamzadeh, Y.; Farzad, F.S.; Salamzadeh, A.; Palalić, R. Digital Leadership and Organizational Capabilities in Manufacturing Industry: A Study in Malaysian Context. Period. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2021, 10, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, D.S.M. Employee Performance as Affected by the Digital Training, the Digital Leadership, and Subjective Wellbeing during COVID-19. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 540–553. [Google Scholar]

- Erhan, T.; Uzunbacak, H.H.; Aydin, E. From Conventional to Digital Leadership: Exploring Digitalization of Leadership and Innovative Work Behavior. Manag. Res. Rev. 2022, 45, 1524–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihardjo, L.; Sasmoko, S.; Alamsjah, F.; Elidjen, E. Digital Leadership Role in Developing Business Model Innovation and Customer Experience Orientation in Industry 4.0. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 1749–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Husban, D.A.O.; Almarshad, M.N.D.; Altahrawi, M.A. Digital Leadership and Organization’s Performance: The Mediating Role of Innovation Capability. Int. J. Entrep. 2021, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Muniroh, M.; Hamidah, H.; Abdullah, T. Managerial Implications on the Relation of Digital Leadership, Digital Culture, Organizational Learning, and Innovation of the Employee Performance (Case Study of PT. Telkom Digital and next Business Department). Manag. Entrep. Trends Dev. 2022, 1, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edquist, C. Systems of Innovation Perspectives and Challenges. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2010, 2, 14–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuze, M. Participation, Remediation, Bricolage: Considering Principal Components of a Digital Culture. Inf. Soc. 2006, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerr, S.; Holotiuk, F.; Beimborn, D.; Wagner, H.-T.; Weitzel, T. What Is Digital Organizational Culture? Insights from Exploratory Case Studies. In Proceedings of the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hilton Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2018; pp. 5126–5135. [Google Scholar]

- Khin, S.; Ho, T.C. Digital Technology, Digital Capability and Organizational Performance: A Mediating Role of Digital Innovation. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2018, 11, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlNuaimi, B.K.; Kumar Singh, S.; Ren, S.; Budhwar, P.; Vorobyev, D. Mastering Digital Transformation: The Nexus between Leadership, Agility, and Digital Strategy. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhari, K.; Ostroff, C.; Barcellos, B.; Williams, D. Co-Governance in Digital Transformation Initiatives: The Roles of Digital Culture and Employee Experience. In Proceedings of the 54th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauai, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weritz, P.; Braojos, J.; Matute, J. Exploring the Antecedents of Digital Transformation: Dynamic Capabilities and Digital Culture Aspects to Achieve Digital Maturity. In Proceedings of the AMCIS 2020, Virtual Conference, 10–14 August 2020; Volume 22, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Adie, B.U.; Tate, M.; Cho, W.; Valentine, E. Digital Leaders and Digital Leadership: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. In Pac. Asia Conf. Inf. Syst. 2022, 115, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- El Sawy, O.A.; Kræmmergaard, P.; Amsinck, H.; Vinther, A.L. How LEGO Built the Foundations and Enterprise Capabilities for Digital Leadership. In Strategic Information Management; Galliers, R.D., Leidner, D.E., Simeonova, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 174–201. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol15/iss2/5 (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Aramburu, N.; North, K.; Zubillaga, A.; Salmador, M.P. A Digital Capabilities Dataset From Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises in the Basque Country (Spain). Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, N.B.; Rawson, J.V.; Slade, C.P.; Bledsoe, M. Transformation and Transformational Leadership: A Review of the Current and Relevant Literature for Academic Radiologists. Acad. Radiol. 2016, 23, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belias, D.; Sdrolias, L.; Nikolaos, K.; Koutiva, M.; Koustelios, A. Traditional Teaching Methods vs. Teaching through the Application of Information and Communication Technologies in the Accounting Field: Quo Vadis? Eur. Sci. J. 2013, 9, 73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, A.G.; Mendes, G.H.S.; Ayala, N.F.; Ghezzi, A. Servitization and Industry 4.0 Convergence in the Digital Transformation of Product Firms: A Business Model Innovation Perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 141, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, M.M. Digital Age Discoverability: A Collaborative Organizational Approach. Ser. Rev. 2013, 39, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberer, B.; Erkollar, A. Leadership 4.0: Digital Leaders in the Age of Industry 4.0. Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2018, 7, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K.; Schwarz, E.; Deutinger, N.; Harms, R. The Relationship between Transformational Leadership, Product Innovation and Performancein SMEs. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2008, 21, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, H.; van Beukering, P.; Brouwer, R. Business Models and Sustainable Plastic Management: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeike, S.; Bradbury, K.; Lindert, L.; Pfaff, H. Digital Leadership Skills and Associations with Psychological Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rudito, P.; Sinaga, M.F.N. Digital Mastery, Membangun Kepemimpinan Digital Untuk Memenangkan Era Disrupsi; Gramedia Pustaka Utama: Jakarta City, Indonesia, 2017; ISBN 978-602-03-6663-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lussier, R.N.; Achua, C.F. Leadership: Theory, Application, & Skill Development; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-305-46507-7. [Google Scholar]

- Nylén, D.; Holmström, J. Digital Innovation Strategy: A Framework for Diagnosing and Improving Digital Product and Service Innovation. Bus. Horiz. 2015, 58, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al Ariss, A.; Guo, G.C. Job Allocations as Cultural Sorting in a Culturally Diverse Organizational Context. Int. Bus. Rev. 2016, 25, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sawy, O.; Amsinck, H.; Kraemmergaard, P.; Vinther, A.L. How LEGO Built the Foundations and Enterprise Capabilities for Digital Leadership. MIS Q. Exec. 2016, 15, 141–166. [Google Scholar]

- Punnett, B.J. International Perspectives on Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, M.; Prandelli, E. Communities of Creation: Managing Distributed Innovation in Turbulent Markets. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2000, 42, 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqshbandi, M.M.; Tabche, I. The Interplay of Leadership, Absorptive Capacity, and Organizational Learning Culture in Open Innovation: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 133, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proksch, D.; Rosin, A.F.; Stubner, S.; Pinkwart, A. The Influence of a Digital Strategy on the Digitalization of New Ventures: The Mediating Effect of Digital Capabilities and a Digital Culture. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassellier, G.; Reich, B.H.; Benbasat, I. Information Technology Competence of Business Managers: A Definition and Research Model. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 17, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, T.; Gemünden, H.G. The Impact of a Company’s Business Strategy on Its Technological Competence, Network Competence and Innovation Success. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.; Rebecca Reuber, A. Online Entrepreneurial Communication: Mitigating Uncertainty and Increasing Differentiation via Twitter. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 565–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BarNir, A.; Gallaugher, J.M.; Auger, P. Business Process Digitization, Strategy, and the Impact of Firm Age and Size: The Case of the Magazine Publishing Industry. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 789–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iivari, M.M.; Ahokangas, P.; Komi, M.; Tihinen, M.; Valtanen, K. Toward Ecosystemic Business Models in the Context of Industrial Internet. J. Bus. Model. 2016, 4, 42–59. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, G.A.; Cavusgil, S.T. Innovation, Organizational Capabilities, and the Born-Global Firm. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 35, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulutaş, M.; Arslan, H. Bilişim Liderliği Ölçeği: Bir Ölçek Geliştirme Çalışması. Marmara Üniversitesi Atatürk Eğitim Fakültesi Eğitim Bilim. Dergisi. 2018, 47, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lukas, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J.; Heide, J.B. Why do Customers Get More than They Need? How Organizational Culture Shapes Product Capability Decisions. J. Mark. 2013, 77, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosin, Z.M.; Pärt, T.; Low, M.; Kotowska, D.; Tobolka, M.; Szymański, P.; Hiron, M. Village Modernization May Contribute More to Farmland Bird Declines than Agricultural Intensification. Conserv. Lett. 2021, 14, e12843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeseok, L.; Byounggu, C. Knowledge Management Enablers, Processes, and Organizational Performance: An Integrative View and Empirical Examination. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 20, 179–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making Sense of Cronbach’s Alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-13-813263-7. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, W.J.; Xia, W.; Torkzadeh, G. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the End-User Computing Satisfaction Instrument. MIS Q. 1994, 18, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, H.; Homburg, C. Applications of Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing and Consumer Research: A Review. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1996, 13, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in Experimental and Nonexperimental Studies: New Procedures and Recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator–Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Luecken, L.J. How and for Whom? Mediation and Moderation in Health Psychology. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, S99–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Preacher, K.J. Conditional Process Modeling: Using Structural Equation Modeling to Examine Contingent Causal Processes. In Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course, 2nd ed; Quantitative Methods in Education and the Behavioral Sciences: Issues, Research, and Teaching; IAP Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2013; pp. 219–266. ISBN1 978-1-62396-244-9. ISBN2 978-1-62396-245-6. ISBN3 978-1-62396-246-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mihardjo, L.; Furinto, A. The Effect of Digital Leadership and Innovation Management for Incumbent Telecommunication Company in the Digital Disruptive Era. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

| Fit Index | Recommended Value | Model and Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 * | Factors 2 ** | Factors 3 *** | Factors 4 **** | ||

| x2 | >0.05 | - | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| x2/df | <2.50 | - | 2.348 | 2.287 | 1.836 |

| GFI | >0.80 | 1.000 | 0.887 | 0.831 | 0.876 |

| AGFI | >0.80 | - | 0.827 | 0.772 | 0.826 |

| RMR | <0.08 | 0.000 | 0.043 | 0.043 | 0.029 |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.357 | 0.095 | 0.903 | 0.075 |

| NFI | >0.90 | 1.000 | 0.921 | 0.891 | 0.925 |

| CFI | >0.90 | 1.000 | 0.953 | 0.935 | 0.964 |

| TLI | >0.90 | - | 0.940 | 0.923 | 0.956 |

| Construct | Indicators | Factor Loading | Standard Error | t-Value | p-Value | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Leadership | DL1 | 0.826 | 0.000 | 0.778 | 0.933 | 0.915 | ||

| DL2 | 0.878 | 0.073 | 11.978 | 0.000 | ||||

| DL5 | 0.857 | 0.064 | 11.132 | 0.000 | ||||

| DL6 | 0.860 | 0.000 | 11.255 | 0.000 | ||||

| Digital Culture | DC2 | 0.854 | 0.000 | 0.711 | 0.811 | 0.877 | ||

| DC4 | 0.869 | |||||||

| DC5 | 0.812 | 0.079 | 12.790 | 0.000 | ||||

| Employees’ Digital Capabilities | EDC1 | 0.806 | 0.000 | 0.682 | 0.859 | 0.875 | ||

| EDC2 | 0.817 | |||||||

| EDC3 | 0.765 | |||||||

| EDC5 | 0.848 | 0.126 | 10.886 | 0.000 | ||||

| Organizational Performance | OP1 | 0.899 | 0.000 | 0.811 | 0.955 | 0.946 | ||

| OP2 | 0.857 | 0.064 | 15.514 | 0.000 | ||||

| OP3 | 0.879 | 0.073 | 15.983 | 0.000 | ||||

| OP4 | 0.879 | 0.058 | 17.219 | 0.000 | ||||

| OP5 | 0.897 | 0.080 | 16.129 | 0.000 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Leadership | 0.882 | |||

| Digital Culture | 0.778 ** | 0.825 | ||

| Employees’ Digital Capabilities | 0.743 ** | 0.843 ** | 0.843 | |

| Organizational Performance | 0.743 ** | 0.828 ** | 0.814 ** | 0.900 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Types of organizations | 4.127 | 2.590 | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Organization Size | 2.933 | 0.949 | 0.318 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Experience | 2.570 | 0.560 | 0.001 | 0.263 ** | 1 | |||||

| 4. Employee Position | 1.973 | 0.479 | −0.024 | 0.234 ** | 0.486 ** | 1 | ||||

| 5. Digital Leadership | 3.909 | 0.794 | 0.004 | −0.006 | 0.068 | 0.163 * | 1 | |||

| 6. Digital Culture | 3.664 | 0.919 | 0.061 | −0.072 | 0.090 | 0.164 * | 0.778 ** | 1 | ||

| 7. Employees’ Digital Capabilities | 3.726 | 0.782 | 0.044 | −0.041 | 0.131 | 0.229 ** | 0.743 ** | 0.843 ** | 1 | |

| 8. Organizational Performance | 3.578 | 0.850 | 0.066 | −0.055 | 0.120 | 0.230 ** | 0.743 ** | 0.828 ** | 0.814 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shin, J.; Mollah, M.A.; Choi, J. Sustainability and Organizational Performance in South Korea: The Effect of Digital Leadership on Digital Culture and Employees’ Digital Capabilities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032027

Shin J, Mollah MA, Choi J. Sustainability and Organizational Performance in South Korea: The Effect of Digital Leadership on Digital Culture and Employees’ Digital Capabilities. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032027

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Jinkyo, Md Alamgir Mollah, and Jaehyeok Choi. 2023. "Sustainability and Organizational Performance in South Korea: The Effect of Digital Leadership on Digital Culture and Employees’ Digital Capabilities" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032027

APA StyleShin, J., Mollah, M. A., & Choi, J. (2023). Sustainability and Organizational Performance in South Korea: The Effect of Digital Leadership on Digital Culture and Employees’ Digital Capabilities. Sustainability, 15(3), 2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032027