An Assessment of Economic Sustainability and Efficiency in Small-Scale Broiler Farms in Limpopo Province: A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Overview of the South African Broiler Industry

Broiler Industry in the Limpopo Province

4. Factors That Influence Broiler Farming

4.1. Broiler House Set Up

4.2. Stocking Density

4.3. Temperature Management

4.4. Ventilation

4.5. Lighting

4.6. Water

4.7. Broiler Feed

4.8. Growth Rate

4.9. Mortality

5. Other Factors Contributing to Good Broiler Farming Management Practices

5.1. Biosecurity and Vaccination

5.2. Record Keeping

5.3. Farmer’s Age

5.4. Size

6. Drivers for Technical and Economic Efficiencies in Broiler Production

6.1. Approaches in Studying Efficiency

6.2. Economic Efficiency

6.3. Allocative Efficiency

6.4. Resources-Use Efficiency in of Small-Scale Broiler Production

6.5. Cost-Benefit Analysis

6.6. Gross Margin Analysis

6.7. Economic Sustainability in Small-Scale Broiler Farms

7. Profitability of Small-Scale Broiler Producer

7.1. Access and Quality of Day-Old Chicks

7.2. Flock Size

7.3. Cycle Length

7.4. Access to Finance

7.5. Marketing

7.6. Farming Experience and Educational Level

7.7. Training

8. Challenges Faced by Small-Scale Broiler Farmers

8.1. Access to Production Inputs

8.2. Poor Physical and Institutional Infrastructure

8.3. Educational Levels

8.4. Breed

8.5. Lack of Knowledge

8.6. Water Supply

8.7. Marketing

- Contract growers (keep 40,000 chickens and supply them to their strategic partners)

- Small scale-market-assured (their capacity ranges from 5001 to 10,000 chickens, and they supply them to local distributors)

- Small scale-infrastructure subsidized (their capacity ranges from 2501 to 5000 chickens, and they supply them to local distributors)

- Resource-poor (their capacity ranges from 1000 to 2500 chickens, and they supply them to local distributors). By comprehending the management practice criteria for broiler farmers, the effectiveness of the business may be monitored. Despite the numerous challenges faced by small-scale producers in Ghana’s Brong Ahafo Region, broiler production was found to be profitable [161]. Oladeebo and Ambe-Lamidi [180] demonstrated that chicken farming was successful among young farmers.

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| HPAI | Highly pathogenic avian influenza |

| SAPA | South African Poultry Association |

| AFMA | Animal Feed Manufacturers Association |

| DAFF | Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries |

| DALRRD | Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development |

| SFA | Stochastic frontier approach |

| DEA | Data envelopment analysis |

| MVP | Marginal value product |

| MFC | Marginal factor cost |

| NFI | Net farm income |

| GI | Gross income |

| NAMC | National Agricultural Marketing Council |

References

- Nkukwana, T.T. Global poultry production: Current impact and future outlook on the South African poultry industry. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 48, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queenan, K.; Cuevas, S.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Chimonyo, M.; Slotow, R.; Häsler, B. A qualitative analysis of the commercial broiler system, and the links to consumers’ nutrition and health, and to environmental sustainability: A South African case study. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 650469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlozi, M.R.S.; Minga, U.M.; Mtambo, A.M.; Kakengi, A.M.V.; Olsen, J.E. Marketing of free range local chicken in Morogoro and Kilosa urban markets. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2000, 15, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Moreki, J.C. Poultry meat production in Botswana. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2011, 3, 7. Available online: http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd23/7/more23163.htm (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development. A Profile of the South African Broiler Market Value Chain. 2020. Available online: https://www.dalrrd.gov.za/doaDev/sideMenu/Marketing/Annual%20Publications/Broiler%20Market%20Value%20Chain%20Profile%202020.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Attia, Y.A.; Rahman, M.T.; Hossain, M.J.; Basiouni, S.; Khafaga, A.F.; Shehata, A.A.; Hafez, H.M. Poultry Production and Sustainability in Developing Countries under the COVID-19 Crisis: Lessons Learned. Animals 2022, 12, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.A.D.; Rankin, M. Contract Farming for Inclusive Market Access. In Proceedings of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy, 19–21 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Adeyonu, A.G.; Odozi, J.C. What are the Drivers of Profitability of Broiler Farms in the North-central and South-west Geo-political Zones of Nigeria? SAGE Open 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachev, H. Sustainability of farming enterprise—Understanding, governance, evaluation. Ekohomika 2016, 2, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, D.; Ranjbar, Z.; Karami, E. Measuring agricultural sustainability. In Biodiversity, Biofuels, Agroforestry and Conservation Agriculture; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sharafat, A.; Al-Deseit, B.; Al-Masad, M. An assessment of economic sustainability in broiler enterprises: Evidence from Jordan. Asian J. Agric. Rural Dev. 2020, 10, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicka, J.; Hlavsa, T.; Soukupova, K.; Stolbova, M. Approaches to estimation the farm-level economic viability and sustainability in agriculture: A literature review. Agric. Econ. 2019, 65, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hennessy, T.; O’brien, M. Is Off-farm income driving on-farm investment? J. Farm Manag. 2008, 13, 235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, A.S. Forage based animal production systems and sustainability, an invited keynote. Rev. Bras. De Zootecnia 2008, 37, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mueller, S. Evaluating the Sustainability of Agriculture: The Case of the Reventado River Watershed in Costa Rica; Peter Lang GmbH: Frankfurt, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sonaiya, E.B. Some technical and socioeconomic factors affecting productivity and profitability of smallholder family poultry. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2009, 65, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.S.; Hossain, M.M. Factors influencing the performance of farmers in broiler production of Faridpur District in Bangladesh. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2010, 66, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Poultry Association. Industry Profile. 2020. Available online: https://www.sapoultry.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/SAPA-INDUSTRY-PROFILE-2020.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- The Africa Livestock Meat Fisheries Summit. Business Opportunity Fair & Expo 2016 14–15 July 2016 Durban ICC, KwaZulu-Natal. Available online: http://www.rmaa.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Fact-Sheet-ALMFS-2016.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Mhlongo, S.R. The Profitability, Feeding Regimes and Contribution of Small-Scale Poultry Production Projects to Rural Household Livelihood Security in KwaMkhwanazi Traditional Ward, Kwazulu Natal, South Africa. Master’s Dissertation, University of Zululand, Richards Bay, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mbuza, F.; Manishimwe, R.; Mahoro, J.; Simbankabo, T.; Nishimwe, K. Characterization of broiler poultry production system in Rwanda. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2017, 49, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hossain, M.A.; Amin, J.R.; Hossain, M.E. Feasibility study of cassava meal in broiler diets by partial replacing energy source (corn) in regard to gross response and carcass traits. Int. J. Agric. Res. Innov. Technol. 2011, 1, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovereign Foods. Meat Seasoning Explained. 2010. Available online: http://www.sovereignfoods.co.za/corporate/files/resources/Meat%20Seasoning%20Explained.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2019).

- Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. South Africa. A Framework for the Development of Smallholder Producers through cooperative Development; Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Luvhengo, U.; Senyolo, M.P.; Belete, A. Socio-economic Determinants of Flock Size in Small-scale Broiler Production in Capricorn District of Limpopo Province, South Africa. J. Hum. Ecol. 2015, 52, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, M.P. Broiler Management. In Commercial Chicken Meat and Egg production; Bell, D.D., Weaver, W.D., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralivhesa, K.; van Averbeke, W.; Siebrits, F.K. Production guidelines for Small-Scale Broiler Enterprises. Pretoria, South Africa. 2013. Available online: https://www.wrc.org.za/wp-content/uploads/mdocs/TT%20568-13.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Mwansa, S. Comparative Investment Analysis for Small Scale Broiler and Layer Enterprises in Zambia. Master’s Thesis, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Heier, T.H.; Hogagen, R.; Jarp, J. Factors associated with mortality in Norwegian broiler flocks. Prev. Vet. Med. 2002, 53, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbaswarup, G.; Majumder, D.; Goswami, R. Broiler performance at different stocking density. Indian J. Anim. Res. 2012, 46, 193. [Google Scholar]

- Benyi, K.; Netshipale, A.J.; Mahlako, K.T.; Gwata, E.T. Effect of genotype and stock density on broiler performance during two subtropical seasons. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2015, 47, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwumba, F.; Lamidi, A.I. Profitability and economic Efficiency of Poultry Local Government Area of Anambra State. J. Poult. Sci. 2011, 10, 106–109. [Google Scholar]

- Melluzi, A.; Sirri, F. Welfare of broiler chickens. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 8, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tyson, J. Cases of ventilation problems in South Africa. Poult. Bull. 1995, 459–460. [Google Scholar]

- South African Poultry Association. Code of Practice for Broiler Production. 2012. Available online: https://www.sapoultry.co.za/pdf-docs/code-practice-broilers.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Mtileni, B.J.; Nephawe, K.A.; Nesamvuni, A.E.; Benyi, K. The influence of stocking density on body weight, egg weight, and feed intake of adult broiler breeder hens. Poult. Sci. 2007, 86, 1615–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abudabos, A.M.; Samara, E.; Hussein, E.O.S.; Al-Atiyat, R.M.; Alhaidary, A. Influence of stocking density on welfare indices of broilers. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 12, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Škrbić, Z.; Pavlovski, Z.; Lukić, M. Stocking density—Factor of production performance, quality and broiler welfare. Biotechnol. Anim. Husb. 2009, 25, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nembilwi, D. Evaluation of Broiler Performance under Small-Scale and Semi-Commercial Farming Conditions in the Northern Province. Master’s Thesis, George Campus, Port Elizabeth, South Africa, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A.L. The effect of stocking density on the welfare and behavior of broiler birds reared commercially. Anim. Welf. 2001, 10, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs, S.; Keeling, L.; Rettenbacher, S.; Van Poucke, E.; Tuyttens, F. Stocking density effects on broiler welfare: Identifying sensitive ranges for different indicators. Poult. Sci. 2009, 88, 1536–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petek, M.; Cibik, R.; Yildiz, H.; Sonat, F.A.; Gezen, S.S.; Orman, A.; Aydin, C. The influence of different lighting programs, stocking densities and litter amounts on the welfare and productivity traits of a commercial broiler line. Vet. Ir Zootechnika. 2010, 51, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Chaudhry, M.A. Inter–regional farm efficiency in Pakistan’s Punjab: A frontier Production function study. J. Agric. Econ. 1990, 41, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghly, M.F.; Mahrose, K.M.; Ahmad, E.A.M.; Rehman, Z.U. Response of broiler to feeding regimes and flashing light in broiler chicks. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 2034–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fivet. Water Consumption in Broilers. Available online: https://www.fivetanimalhealth.com/management-articles/water-consumption-broilers (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Animal Feed Manufacturers Association. Chairman’s Report 2020/2021; AFMA: Pretoria, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, M.B. What You Feed vs. What You Get. FEED Efficiency as an Evaluation Tool; Department of Animal Sciences University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Abed, A.; Karimi, G.H.; Sadeghi, M.; Shivazad, S.; Dashti, A.; Sadeghisefidmaz, G.I. Do broiler chicks possess enough growth potential to compensate long-term feed and water depravation during the neonatal period? S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurofi, I.; Ismail, M.M.; Kamal, H.A.W.; Gabdo, B.H. Economic analysis of broiler production in Peninsular Malaysia. Int. Food Res. J. 2017, 24, 761–766. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, N.U.; Mehmood, S.; Ahmad, S.; Javid, A.; Mahmud, A.; Hussain, J.; Shaheen, M.S.; Usman, M.; Mohayud Din Hashmi, S.G. Production analysis of broiler farming in central Punjab, Pakistan. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siliga, H.P. Modelling the Broiler Performance under Small-Scale and Semi-Commercial Management Condition. Ph.D. Dissertation, George. Port Elizaberth Technikon (Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University), Port Elizaberth, South Africa, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, A.A.; Nwanta, J.A.; Njoga, E.O.; Maiangwa, M.G.; Mohammed, A. Economic Analysis of feed source in Broiler production. Niger. Vet. J. 2011, 32, 154–156. [Google Scholar]

- Mallick, P.; Muduli, K.; Biswal, J.N.; Pumwa, J. Broiler poultry feed cost optimization using linear programming technique. J. Oper. Strateg. Plan. 2020, 3, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawsar, M.H.; Chowdhury, S.D.; Raha, S.K.; Hossain, M.M. An analysis of factors affecting the profitability of small-scale broiler farming in Bangladesh. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2013, 69, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziwornu, R.K.; Seini, W.; Sarpong, D.B.; Kwadzo, G.T.M.; Kuwornu, J.K. Does Scale Matter in Profitability of Small Scale Broiler Agribusiness Production in Ghana? A translog profit function model. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 4, 128–138. [Google Scholar]

- Dziwornu, R.K.; Sarpong, D.B. Application of the stochastic profit frontier model to estimate economic efficiency in small-scale broiler production in the Greater Accra region of Ghana. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2014, 2, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, G.A. The effect of broiler market age on performance parameters and economics. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2008, 10, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baéza, E.; Arnould, C.; Jlali, M.; Chartrin, P.; Gigaud, V.; Mercerand, F.; Durand, C.; Méteau, K.; Le Bihan-Duval, E.; Berri, C. Influence of increasing slaughter age of chickens on meat quality, welfare, and technical and economic results. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 90, 2003–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szőllősi, L.; Szűcs, I.; Nábrádi, A. Economic issues of broiler production length. Agric. Econ. 2014, 61, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ndiyoi, M.; Chikazunga, D.; Muloongo, O. Restructuring Food Markets in Zambia: Dynamics in Beef and Chicken Subsectors; IIED Regoverning Markets Agrifood Sector Studies; IIED: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ajewolwe, O.C.; Akinwunmi, A.A. Awareness and practice of biosecurity measuresing small scale poultry production in Ekiti State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 2014, 7, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Oluwasusi, J.O.; Akanni, Y.O.; Sodiq, A.R. Effectiveness and Benefits of Biosecurity Practices in Small Scale Broiler Farmers in Ekiti State. Niger. Poult. Sci. J. 2018, 15, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Negro-Calduch, E.; Elfadaly, S.; Tibbo, M.; Ankers, P.; Bailey, E. Assessment of biosecurity practices of small-scale broiler producers in central Egypt. Prev. Vet. Med. 2013, 110, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yitbarek, M.B.; Mersso, B.T.; Wosen, A.M. Disease management and biosecurity measures of small-scale commercial poultry farms in and around Debre Markos, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. J. Vet. Med. Anim. Health 2016, 8, 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, T.H.; Gomes, P.I. A Profile of Small Farming in St Vincent, Dominica, and St Lucia: Report of a Baseline Survey; Department of Agricultural Extension, The University of the West Indies: St. Augustine Campus, Trinidad and Tobago, 1979; pp. 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tham-Agyekum, E.K.; Appiah, P.; Nimoh, F. Assessing farm record keeping behavior among small-scale poultry farmers in the Ga East Municipality. J. Agric. Sci. 2010, 2, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J.C.; Johnson, D.M.; Lesley, B.V. Developing and Improving your Farm Records; Department of Agriculture, University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Poggio, M. Farm Management Records. 2006. Available online: www.srdc.gov.au (accessed on 4 November 2017).

- Johl, S.S.; Kapur, T.R. Fundamentals of Farm Business Management; Kalyani Publishers: New Delhi, India, 2001; pp. 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Minna-Eyovwunu, D.; Akarue, B.O.; Emorere, S.J. Effective Record Keeping and Poultry Management in Udu and Okpe Local Government Areas of Delta State, Nigeria. Int. J. Innov. Agric. Sci. 2019, 7, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dudafa, U.J. Record keeping among small farmers in Nigeria: Problems and prospects. Int. J. Sci. Res. Educ. 2013, 6, 214–220. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, S.; Hughes, J.D.; Allen, W.H. Growth and waste production of broilers during brooding. Poult. Sci. 1987, 66, 762–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahiale, D.; Abunyuwah, I.; Yenibeh, N. Technical Efficiency Analysis of Broiler Production in the Mampong Municipality of Ghana Evelyn. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 10, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Chavanapoonphol, Y.; Battese, G.E.; Chang, H.C. The impact of rural financial services on the technical efficiency of rice farmers in the upper North of Thailand. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society, Coffs Harbour, NSW, Australia, 9–11 February 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mbanasor, J.A.; Kalu, K.C. Economic efficiency of commercial vegetable production system in Akwa Ibom state, Nigeria: A translog stochastic frontier cost function approach. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2008, 8, 313–318. [Google Scholar]

- Pakage, S.; Hartono, B.; Fanani, Z.; Nugroho, B.A. Analysis of technical efficiency of poultry broiler business with pattern closed house system in Malang East Java Indonesia. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 5, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mahjoor, A.A. Technical, Allocative and Economic Efficiencies of Broiler Farms in Fars Province, Iran: A Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) Approach. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 21, 1427–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Onubogu, G.C.; Chidebelu, S.A.N.D. Technical efficiency evaluation of market age and enterprise size for broiler production in Imo State, Nigeria. Niger. Agric. J. 2012, 43. Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/naj/article/view/110128 (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Effiong, E.O. Efficiency of Production in Selected Livestock Enterprises in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Ph.D. Dissertation, Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Umudike, Nigeria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nwachukwu, I.N.; Onyenweaku, C.E. Economic Efficiency of Fadama Telfairia Production in Imo State, Nigeria: A Translog Profit Function Approach. J. Agric. Res. Policies Niger. 2007, 2, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Yusef, S.A.; Malomo, O. Technical efficiency of poultry egg production in Ogun state: A data envelopment analysis (DEA) approach. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2007, 6, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Etim, N.A.; Udoh, E.J. Measuring Technical Efficiency of Broiler Production among Rural Producers in Akwa Ibom State. In Proceedings of the Technical Annual Conference of the Nigeria Society of Animal Production, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria, 18–21 March 2007; pp. 412–414. [Google Scholar]

- Ezeh, C.I.; Anyiro, C.O.; Chukwu, J.A. Technical Efficiency in Poultry Broiler Production in Umuahia Capital Territory of Abia State, Nigeria. Greener J. Agric. Sci. 2012, 2, 001–007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carlson, B. A Study of the Pure Theory of Production; Augustus, M., Ed.; Kelley & Millman Inc: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Coelli, T.J. A Guide to DEAP: A Data Envelopment Analysis (Computer) Program, Version 2.1; Centre for Efficiency and Productivity Analysis, University of New England: Armidale, NSW, Australia, 1996.

- Aigner, D.J.; Lovell, C.A.K.; Schmidt, P. Formulation and Estimation of Stochastic Frontier Function models. J. Econ. 1977, 1, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farell, M.J. The measurement of Productive Efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc. A Gen. 1957, 120, 253–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukelić, N.; Novković, N. Economic efficiency of broiler farms in Vojvodina region. In Proceedings of the Seminar Agriculture and Rural Development—Challenges of Transition and Integration Processes. 50th Anniversary Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 27 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis, 5th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nyekanyeka, T. Analysis of Profitability and Efficiency of Improved and Local Smallholder Dairy Production: A Case of Lilongwe Milk Shed Area. Master’s Thesis, University of Malawi Bunda College, Mwenda, Malawi, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardi, V.; Ramankutty, N.; Mehrabi, Z.; Jarvis, L.; Chookolingo, B. How much of the world’s food do smallholders produce? Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 17, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyenweaku, C.E.; Igwe, K.C.; Mbanasor, J.A. Application of the Stochastic Frontier Production Function to the Measurement of Technical Efficiency in Yam Production in Nasarawa State, Nigeria. J. Sustain. Trop. Agric. Res. 2004, 13, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ng’eno, V.B.K. Resource Use Efficiency in Poultry Production in Bureti District, Kenya. Afr. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Fawwaz, T.M.; Al-Sharafat, A. Estimation of resource use efficiency in broiler farms: A marginal analysis approach. Glob. J. Financ. Bank. 2013, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9Akinwumi, A.A.; Djato, K.K. Relative efficiency of women as farm managers: Profit function analysis in Côte d’Ivoire. Agric. Econ. 1997, 16, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Yeni, A. Economic Structure and Efficiency Analysis of Production Coops in the Turkish Broiler Sector: East Marmara Case. Ph.D. Thesis, Ataturk University, Erzurum, Turkey, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nwaru, J.C. Relative Production Efficiency of Cooperative and Non-Cooperative Farms in Imo State, Nigeria. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Nigeria, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S. Technological Change, Technical and Allocative Efficiency in Chinese Agriculture: The Case of Rice Production. in China. J. Int. Dev. J. Dev. Stud. Assoc. 2000, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeano, C.I.; Ohaemesi, C.F. Comparative analysis of broiler and turkey production in Anambra State, Nigeria. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2020, 9, 511–515. [Google Scholar]

- Ike, P.C.; Ugwumba, C.O.A. Profitability of Small Scale Broiler Production in Onitsha North Local Government Area of Anambra State, Nigeria. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2011, 10, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Ali, S.; Khan, S.U.; Sajjad, M. Assessment of technical efficiency of open shed broiler farms: The case study of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province Pakistan. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruna, E.O.; Samuel, E.E.; Ibinayo, B.T. Economic and scale efficiency of broiler production in the federal capital territory, Abuja Nigeria: A data envelopment analysis approach. Russ. J. Agric. Soc.-Econ. Sci. 2020, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ike, P.C. Estimating production technical efficiency of Irvingia seed (ogbono) species farmers in Nsukka Agricultural zone of Enugu State, Nigeria. J. Sustain. Agric. Res. 2008, 28, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nmadu, J.; Ogidan, I.; Omolehin, R. Profitability and resource use efficiency of poultry egg production in Abuja, Nigeria. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 35, 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, K. The Fundamentals of Forward Contracting, Hedging and Options for Dairy Producers in the North East; Staff Paper no.338; College of Agricultural Sciences, The Pennsylvannia State University: State College, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bamire, A.S.; Fabiyi, Y.L.; Manyong, V.M. Adoption pattern of fertilizer technology among farmers in the ecological zones of Southwestern Nigeria: A Tobit analysis. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2002, 53, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ament, A.J.; Jansen, J.; van de Giessen, A.; Notermans, S. Cost-benefit analysis of a screening strategy for Salmonella enteritiisin poultry. Vet. Quart. 1993, 15, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devonish, E.; Pemberton, C.A.; Ragbir, S. Record Keeping among Small Farmers in Barbados; Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, University of the West India: St. Augustine, Trividad and Tabago, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt, J.P. How do You Determine the Cost-Benefit of a Biosecurity System? Dept. of Farm Animal Health and Resource Management, North Carolina State Univ.: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2001; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Nworgu, F.C.; Egbunike, G.N. Performance and nitrogen utilization of broiler chicks fed full fat extruded soybean meal and full fat soybean. Trop. Anim. Prod. Invest. J. 2000, 3, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Balamurugan, V.; Manoharana, M. Cost and benefit of investment in integrated broiler farming-A case study. Int. Curr. Res. Acad. Rev. 2013, 2, 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Chamdimba, C. An Analysis of Technical Efficiency of Mixed Intercropping and Relay Cropping Agro Forestry Technologies in Malawi: A Case of Zomba District in Malawi. Master’s Thesis, University of Malawi, Zomba, Malawi, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.T. A Guide to Farm Business Management in the Tropics; Macmillan Press: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Olukosi, J.O.; Erhabo, P.O. Introduction to Farm Management Economics: Principles and Applications; Agitab Publishers Ltd.: Zaria, Nigeria, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bachev, H.I. An Approach to Assess Sustainability of Agricultural Farms. Turk. Econ. Rev. 2016, 3, 28–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bossel, H. Indicators for Sustainable Development: Theory, Method, Applications: A Report to the Balaton Group/Hartmut Bossel; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Latruffe, L.; Diazabakana, A.; Bockstaller, C.; Desjeux, Y.; Finn, J.; Kelly, E.; Ryan, M.; Uthes, S. Measurement of sustainability in agriculture: A review of indicators. Stud. Agric Econ. 2016, 118, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenz, J. Response-Inducing Sustainability Evaluation (RISE); Bern University of Applied Sciences: Bern, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, D. Crucial agriculture problems facing small producers. Polit. Econ. J. India 2001, 10, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishna, M.; Bhavani, D.I.; Rajeswari, S.; Satyagopal, P.V.; Mohan, N.G. Factors Influencing Economic Viability of Small and Marginal Farms in Rayalaseema Region of Andhra Pradesh, India. J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2021, 39, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Bhullar, A.S.; Joshi, A.S. Factors Influencing Economic Viability of Marginal and Small Producers in Punjab. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev. 2009, 22, 269–279. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donoghue, C.; Devisme, S.; Ryan, M.; Conneely, R.; Gillespie, P.; Vrolijk, H. Farm economic sustainability in the European Union: A pilot study. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2016, 118, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slavickienė, A.; Savickienė, J. The evaluation of small and medium farms’ economic viability in the new EU countries. J. Int. Sci. Publ. 2014, 8, 843–855. [Google Scholar]

- Ettah, O.I.; Igiri, J.A.; Ihejiamaizu, V.C. Profitability of broiler production in cross river state, Nigeria. Glob. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 20, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, R.; Shah, H.; Sharif, M.; Akhtar, W. Profitability index and capital turn over in open house broiler farming: A case study of district Rawalpindi. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 24, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mamun Rana, K.M.A.; Rahman, M.S.; Sattar, M.N. Profitability of small scale broiler production in some selected areas of Mymensingh. Progress. Agric. 2013, 23, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siyaya, B.J.; Masuku, M.B. Determinants of profitability of indigenous chickens in Swaziland. Bus. Econ. Res. 2013, 3, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.S.R.C.; Chowdhury, M.M. Profitability analysis of poultry farming in Bangladesh: A case study on Trishal upazilla in Mymensingh district. Dev. Ctry. Stud. 2015, 5, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.M. Application of stochastic frontier model for poultry broiler production: Evidence from Dhaka and Kishoreganj Districts, Bangladesh. Bangladesh Dev. Stud. 2018, 1, 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Milán, M.J.; Frendi, F.; González-González, R.; Caja, G. Cost structure and profitability of Assaf dairy sheep farms in Spain. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 5239–5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nehringa, R.; Gillespie, J.; Katchovac, A.L.; Hallahand, C.; Harrise, J.M.; Ericksonf, K. What’s Driving U.S. Broiler Farm Profitability? Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, M.G.; Kollins, K.W. Determinants of profitability of agricultural firms listed at the Nairobi securities exchange, Kenya. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2016, 4, 225–235. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Afzal, M. Profitability analysis of different farm size of broiler poultry in district Dir (lower). Sarhad J. Agric. 2018, 34, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulaudzi, R.G. Socio-Economic Analysis and Profitability of Small-Scale Broiler Production Enterprises in Vhembe District, Limpopo Province. Master’s Dissertation, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Daghir, N.J. Poultry Production in Hot Climates, 2nd ed.; Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences, American University of Beirut: Beirut, Lebanon; British Library: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Durrani, M.F. Production performance and economic appraisal of commercial layers in district Chakwal. Master’s Thesis, NWFP Agricultural University, Peshawar, Pakistan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sarıözkan, S. Profitability and Productivity Analysis in Laying Hen Enterprises in Afyon District. Ankara (TUR): Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Çiçek, H.; Günlü, A.; Tandoğan, M. The factors affecting profitability in layer hen enterprises in Southern West Region of Turkey. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2008, 62, 286–289. [Google Scholar]

- Etuah, S.; Gyiele, K.; Akwasi, O. Profitability and constraints of broiler production: Empirical evidence from Ashanti region of Ghana. J. Bus. Econ. 2013, 5, 228–243. [Google Scholar]

- Aryemo, I.P.; Akite, I.; Kule, E.K.; Kugonza, D.R.; Okot, M.W.; Mugonola, B. Drivers of commercialization: A case of indigenous chicken production in northern Uganda. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2019, 11, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleyn, R. Strategies for Managing Expensive Feed on Farm; Spesfeed Ltd: Rivonia, South Africa, 2002; Available online: http://spesfeed.com/?wpdmact=process&did=NDQuaG90bGluaw (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Samarakoon, S.M.R.; Samarasinghe, K. Strategies to improve the cost effectiveness of broiler production. Trop. Agric. Res. 2012, 23, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, E. The State of Livestock Industry in Nigeria; EK-OVET Magazine; Publication of Nigerian Veterinary Medical Association (NVMA), Lagos State Branch: Abuja, Nigeria, 1991; Volume 6, pp. 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Adeyemo, A.A.; Adeyemo, F.T. Problems militating against commercial egg production in the Southern Guinea Savannah of Nigeria. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of Animal Science of Nigeria, Department of Animal Production and Health, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomosho, Nigeria, 14–17 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Akanni, K.A. Effect of microfinance on small poultry business in south-western Nigeria. J. Food Agric. 2007, 19, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, S.; Chima, C. Determinants of food crop diversity and profitability in southeastern Nigeria: A multivariate tobit approach. Agriculture 2016, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, W.; Mushtaq, Z.; Ikram, A.; Faisal, M.; Wan-Li, Z.; Ahmad, M.I. Estimating the economic viability of cotton growers in Punjab province, Pakistan. Sage Open 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeneke, R.U.; Iruo, F.A. Socioeconomic analysis of the effect of microfinance on small scale poultry production in Imo state, Nigeria. Agric. Sci. Res. J. 2012, 2, 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Louw, M.; Davids, T.; Scheltema, N. Broiler production in South Africa: Is there space for smallholders in the commercial chicken coup? Dev. S. Afr. 2017, 34, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nwaogu, R.N. Influence of Fertilizer and Land Prices on Short Run Supply of Cassava in Ikwuano L.G.A. of Abia State, Nigeria. Master’s Thesis, Abia State University, Uturu, Nigeria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Imtiaz, A. Profitability Analysis of Poultry Farming in District Peshawar. Master’s Thesis, University of the Agriculture, Peshawar, Pakistan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.Y.; Jahan, S.S.; Begum, M.I.A.; Islam, A. Impact of bio-security management intervention on growth performance and profitability of broiler farming in Bangladesh. Livest. Res. Rural. Dev. 2014, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Obasi, P.C. Resource Use Efficiency in Food Crop Production: A Case Study of the Owerri Agricultural Zone of Imo State, Nigeria. Master’s Thesis, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Center, Y.T. Efficiency of trained farmers on the productivity of broilers in a selected area of Bangladesh. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2004, 3, 503–506. [Google Scholar]

- Akteruzzaman, M.; Miah, M.A.M.; Hossain, M.M.; Nahar, J.; Fattah, K. Impact of training on poultry farming for improving livelihood of the smallholders in rural Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the 6th International Poultry Show and Seminar, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 5–7 March, 2009; World’s Poultry Science Association: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.S. Prospects and problems of broiler enterprise under contract farming system with particular reference to marketing practices. J. Biol. Sci. 2003, 6, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, B.G.; Pathak, P.K.; Mohanty, A.K. Constraints Analysis of Poultry Production at Dzongu Area of North Sikkim in India. Iran. J. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2012, 2, 397–401. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, S.D. Opportunities and challenges facing commercial poultry production in Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Poultry Show and Seminar, WPSA-BB, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 28 Feburary–2 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tadelle, D.; Million, T.; Yami, A.; Peters, K.J. Village chicken production systems in Ethiopia: Use patterns & performance valuation and chicken products & socioeconomic functions of chicken. Livest. Res. Rural. Dev. 2003, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Anang, B.T.; Anthony, A.A.; Cosmos, Y. Profitability of broiler and layer production in the Brong Ahafo region of Ghana. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2013, 8, 423–430. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, M.H.; Francis, J.; Maliwichi, L.L. Poultry-based poverty alleviation projects in Ehlanzeni district municipality: Do they contribute to the South African government’s ‘developmental state’ ambition? S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 2016, 44, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ntuli, V.; Oladele, O.I. Analysis of Constraints Faced by Small-scale Broiler Producers in Capricorn District in Limpopo Province. Life Sci. J. 2013, 10, 2990–2996. [Google Scholar]

- National Agricultural Marketing Council. The Smallholder Market Access Tracker Baseline Report: A Case of Smallholder Broiler Producers in South Africa. 2020. Available online: https://www.namc.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/SMAT-broiler-baseline-report_2020.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Matungul, M.P.M. Marketing Constraints Faced by Communal Producers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: A Case Study of Transaction Costs. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, S.L.; Lyne, M.C. Agricultural growth multipliers for two communal areas of KwaZulu-Natal. Dev. S. Afr. 2003, 20, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne, A.T.; Lyne, M.C. Rural economic growth linkages and small scale poultry production: A survey of producers in KwaZulu-Natal. Agrekon 2004, 43, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emaikwu, K.K.; Chikwendu, D.O.; Sani, A.S. Determinants of flock size in broiler production in Kaduna State of Nigeria. J. Agric. Ext. Rural. Dev. 2011, 3, 202–211. [Google Scholar]

- Omolayo, J.O. Economic analysis of broiler production in Lagos State Poultry Estate, Nigeria. J. Invest. Manag. 2018, 7, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kumbhakar, S.C. Estimation of profit functions when profit is not maximum. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2001, 83, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, C.A.; Hughes, B.O.; Elson, H.A. Poultry Production System, Behaviour, Management and Welfare; Redwood Press Ltd.: Melkshan, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Begum, I.A.; Buysse, J.; Alam, M.J.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Technical, allocative and economic efficiency of commercial poultry farms in Banglades. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2010, 66, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, S.O. Productivity and Technical Efficiency of Poultry Egg Production in Nigeria. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2003, 2, 459–464. [Google Scholar]

- Kpomasse, C.C.; Oke, K.T.; Houndonougbo, M.; Tona, K. Broiler production challenges in the tropics: A review. Vet. Med. Sci. 2021, 7, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smit, L.; Tona, K.; Bruggeman, V.; Onagbesan, O.; Hassanzadeh, M.; Arckens, L.; Decuypere, E. Comparison of three lines of broilers differing in ascites susceptibility or growth rate. 2. Egg weight loss, gas pressures, embryonic heat production, and physiological hormone levels. Poult. Sci. 2005, 84, 1446–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sil, G.C.; Das, P.M.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, M.M. Management and Disease Problems of Cockerels in some Farms of Mymensingh, Bangladesh. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2002, 1, 102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Badubi, S.S.; Ravindran, V.; Reid, J. A survey of small scale broiler production systems in Botswana. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2004, 36, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groenewald, J.A. Resource use entitlement, finance and entrepreneurship in Sub-Saharan smallholder agriculture. Agrekon 1993, 32, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabelebele, M.; Selapa, W.; Phasha, S.; Masikhwa, H.; Ledwaba, L. The Dynamics of the Poultry Value Chain: A Review of the Broiler Sector in the Greater Tzaneen Municipality. Agric. Res. Dev. 2011, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Oladeebo, J.O.; Ambe-Lamidi, A.I. Profitability, imput elasticities and economic efficiency of poultry production among youth farmers in Osun State, Nigeria. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2007, 6, 994–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Eastern Cape | Free State | Gauteng | KwaZulu- Natal | Limpopo | Mpuma- Langa | North West | Western Cape | SADC | Total [× 1000 t] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy | 194.30 | 40.14 | 32.36 | 240.53 | 0.26 | 34.85 | 25.56 | 373.97 | 0.39 | 942.37 |

| Beef and sheep | 26.85 | 97.82 | 8.70 | 248.06 | 6.12 | 322.10 | 15.39 | 91.64 | 7.11 | 823.80 |

| Pigs | 28.84 | 58.40 | 34.61 | 22.71 | 2.46 | 56.63 | 30.66 | 145.04 | 7.69 | 387.03 |

| Layers | 39.17 | 184.18 | 335.29 | 68.54 | 10.97 | 96.65 | 63.28 | 139.24 | 53.62 | 990.93 |

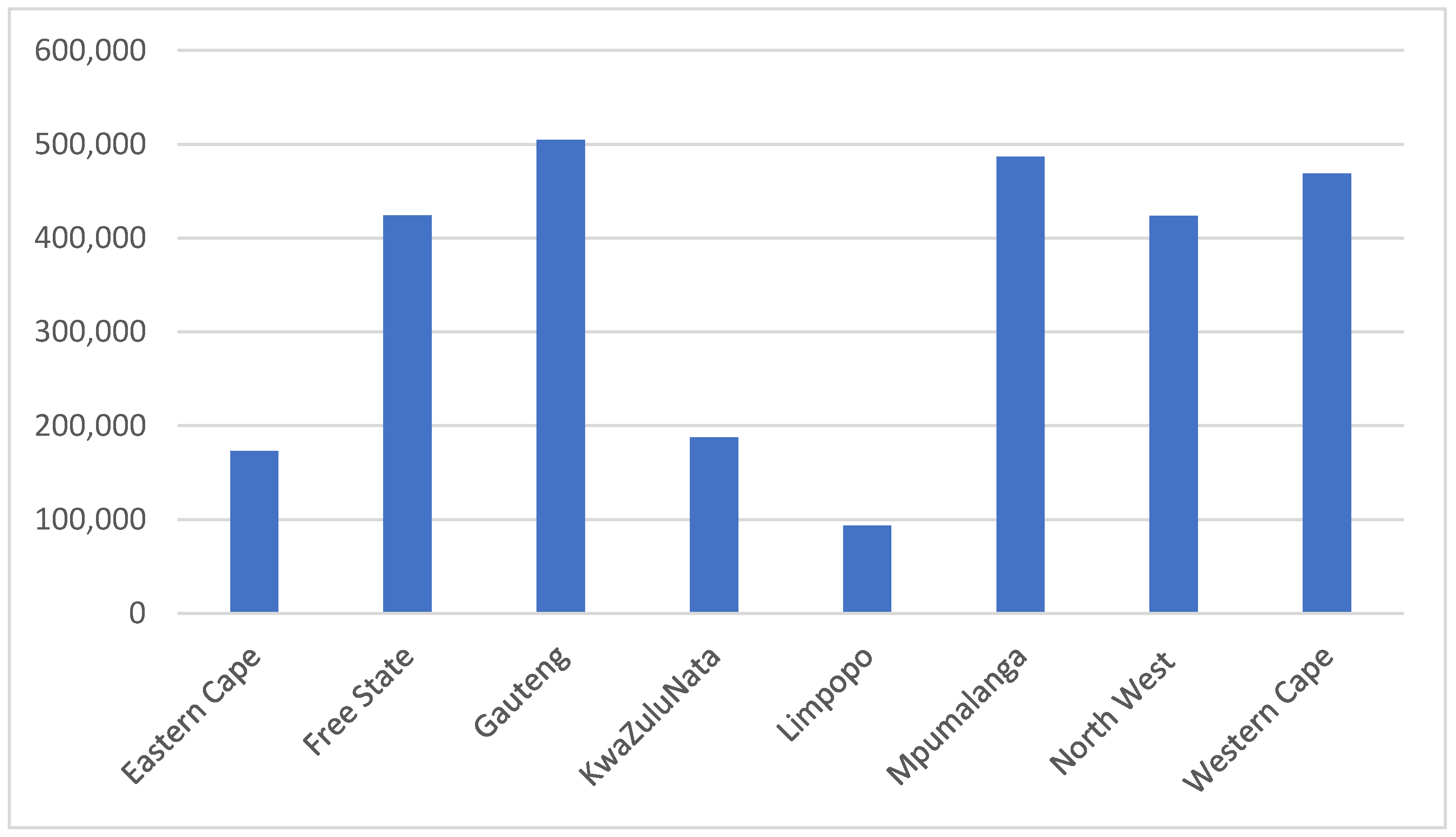

| Broilers | 182.38 | 392.27 | 507.72 | 172.88 | 76.02 | 486.71 | 401.97 | 452.54 | 162.15 | 2 834.63 |

| Broiler breeders | 27.30 | 41.50 | 99.41 | 129.42 | 0.44 | 105.05 | 39.67 | 67.16 | 25.03 | 534.97 |

| Ostriches | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramukhithi, T.F.; Nephawe, K.A.; Mpofu, T.J.; Raphulu, T.; Munhuweyi, K.; Ramukhithi, F.V.; Mtileni, B. An Assessment of Economic Sustainability and Efficiency in Small-Scale Broiler Farms in Limpopo Province: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2030. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032030

Ramukhithi TF, Nephawe KA, Mpofu TJ, Raphulu T, Munhuweyi K, Ramukhithi FV, Mtileni B. An Assessment of Economic Sustainability and Efficiency in Small-Scale Broiler Farms in Limpopo Province: A Review. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2030. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032030

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamukhithi, Tumelo Francinah, Khathutshelo Agree Nephawe, Takalani Judas Mpofu, Thomas Raphulu, Karen Munhuweyi, Fhulufhelo Vincent Ramukhithi, and Bohani Mtileni. 2023. "An Assessment of Economic Sustainability and Efficiency in Small-Scale Broiler Farms in Limpopo Province: A Review" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2030. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032030