Linguistic Repertoires Embodied and Digitalized: A Computer-Vision-Aided Analysis of the Language Portraits by Multilingual Youth

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Theoretical Background: From Linguistic Repertoires to Multilinguistic Repertoires

2.2. A Computer Vision-Aided Analysis of Language Portraits

3. The Current Study

- Compared to the Chinese Mainland sojourners and local Macao heritage speakers, what characterizes the linguistic repertoires of the young Macanese speakers?

- How do these Macanese youth perceive their “scope” and “access” of linguistic resources across different social registers in lived experience in multilingual Macao?

3.1. Participants

3.2. Tasks and Instruments

3.2.1. Background Survey

3.2.2. Language Portrait Task

3.2.3. Follow-Up Interviews

3.3. Data Collection Procedures

3.4. Data Analysis

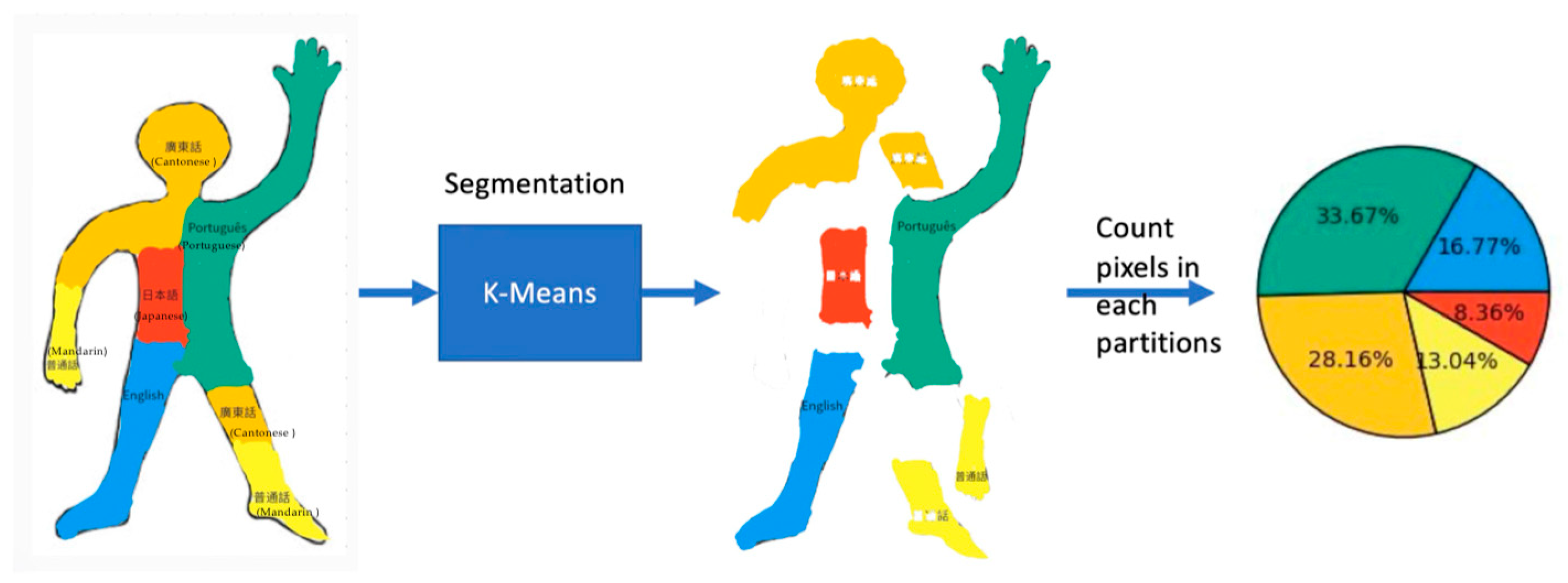

3.4.1. Image Analysis through OpenCV and K-Means

3.4.2. Discourse and Register Analysis

4. Results

4.1. The Richness of Macanese Youths’ Linguistic Repertoires

4.2. The Openness of Macanese Youths’ Linguistic Repertoires

Excerpt 1: (from Isabel) 我係澳門出世同埋長大嘅,呢度係一個雙語制度嘅地方,自然識聽同埋講廣東話同葡文。(⋯) 我對呢兩種語言接受度更高,因為係我嘅母語同埋接觸最多嘅語言。[Literal translation: I was born and grew up in Macao, this is a region administered in a bilingual system, so naturally, I can understand and speak Cantonese and Portuguese. My acceptance of these two languages is higher because they’re the first languages I have met and started to learn.]

4.3. The Scope and Access of Linguistic Resources by Macanese Youths

Excerpt 2: Acho estou competente em falar português com o meu avô, meus colegas na empresa e nos serviços públicos, mas na aula de aula de interpretação, não estou! (…) A dificuldade de dominar bem a terminologia especialmente nas áreas económica e industrial é enorme. (…) Apesar disso, a professora era muito simpática e sempre me presta a paciência em esclarecer dúvidas na interpretação. De forma qualquer, estou no progresso de ser um intérprete qualificado.[Isabel: I think I’m competent in speaking Portuguese with my grandfather and colleagues in the company and public services, but in the interpreting class, I’m not! (…) The difficulty of dominating the terminology well, especially in economic and industrial areas, is quite significant. (…) Even so, my teacher was kind and always responded to my questions by interpreting with patience. No matter what, I’m on the way to being a qualified interpreter].

Excerpt 3: O meu Mandarim é malíssimo… Todas as minhas colegas sabem…Pá, (…) Quando a professora falava com os outros em Mandarim, estava distraída em outra coisa. Mas a minha colega,/amiga, deve ser, ajuda-me em perceber o que estão a conversar e até ensinar-me mandarim no tempo livre. (…)[Isabel: My Mandarin is the worst… All of my classmates know this. (…) When the teacher spoke with others in Mandarin, I was distracted by something. However, my classmate, a friend she should be, helps me comprehend what they are talking about; she even teaches me Mandarin daily].

Excerpt 4: 屋企比較祟尚美國文化,因此,雖然我既父母都識講葡文,但係我地更多以中英兩語交流。[Julietta: My family adores the US culture, so, although my parents speak Portuguese well, we talk with each other more often in Chinese and English].

Excerpt 5: 日文係葡文課堂雖唔係經常出現,但結合日文講解真係可以幫到我領會葡文嘅一些語法點。例如,一次上堂時,老師講este,esse同埋 aquile,點都唔明係邊個方位嘅,梗老師話:“Julietta,esse就係これ,este就係それ,aquile就係あれ嘛?!”咁我就理解咗.[Julietta: Japanese does not frequently occur in Portuguese classrooms, but sometimes it can be helpful for my uptake of Portuguese grammatical knowledge. For example, once I wondered about the meaning of “este, esse and aquile” in Portuguese class, and my teacher said: “Julietta, esse is ko re, este is so re, aquile is a re, ok?” Instantly, I comprehended it].

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Clayton, C.H. Multi-Ethnic Macao: From Global Village to Migrant Metropolis. Soc. Transform. Chin. Soc. 2019, 15, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X. “Macao Has Died, Traditional Chinese Characters Have Died”: A Study of Netizens’ Comments on the Choice of Chinese Scripts in Macao. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2015, 37, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J. Macau or Macao?—A Case Study in the Fluidity of How Languages Interact in Macau SAR. J. Engl. Int. Lang. 2019, 14, 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Wen, Z. Translanguaging and Decolonizing LPP: A Case Study of Translingual Practice in Macau. Glob. Chin. 2022, 8, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Matos, P.F. Colonial Representations of Macao and the Macanese: Circulation, Knowledge, Identities and Challenges for the Future. Port. J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 19, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, M.C. Tempo do Bambu—Identidade e Ambivalência entre Macaenses; Instituto do Oriente: Lisbon, Portugal, 2015; pp. 1–299. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L. Luís Gonzaga Gomes, Sun of the Earth: Spreader and Translator of the Images of China and of Macao; Instituto Politécnico de Macau: Macau, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, H.C.O.; Chui, W.H. Social Bonds and School Bullying: A Study of Macanese Male Adolescents on Bullying Perpetration and Peer Victimization. Child Youth Care Forum 2013, 42, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunsom, T. Lost in Transition: An Analysis of Post-Colonial Dilemma and National Identity in Three Contemporary Novels from East and Southeast Asia. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.F.I.; Ieong, W.I. Translanguaging and Multilingual Society of Macau: Past, Present and Future. Asian-Pac. J. Second Foreign Lang. Educ. 2022, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Moody, A. Language and Society in Macao. Chin. Lang. Discourse 2010, 1, 293–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, B. The Linguistic Repertoire Revisited. Appl. Linguist. 2012, 33, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, B. The Language Portrait in Multilingualism Research: Theoretical and Methodological Considerations. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/35988562/WP236_Busch_2018_The_language_portrait_in_multilingualism_research_Theoretical_and_methodological_considerations (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Dekel, R. Human Perception in Computer Vision. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1701.04674. [Google Scholar]

- Stork, D.G. Computer Vision and Computer Graphics Analysis of Paintings and Drawings: An Introduction to the Literature. Comput. Anal. Images Patterns 2009, 5702, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Weirich, A.-C. Sprachliche Verhältnisse und Restrukturierung Sprachlicher Repertoires in der Republik Moldova; Peter Lang: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–686. [Google Scholar]

- Weirich, A.-C. Access and Reach of Linguistic Repertoires in Periods of Change: A Theoretical Approach to Sociolinguistic Inequalities. Int. J. Sociol. Lang. 2021, 2021, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment, Companion Volume; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdi, G. Multilingual Repertoires and the Consequences for Linguistic Theory. Beyond Misunderstanding 2006, 144, 11–42. [Google Scholar]

- Vertovec, S. Super-Diversity and Its Implications. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2007, 30, 1024–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Källkvist, M.; Hult, F.M. Multilingualism as Problem, Right, or Resource?: Negotiating Space for Languages Other than Swedish and English in University Language Planning. Available online: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-79122 (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Blommaert, J.; Backus, A. Repertoires Revisited: “Knowing Language” in Superdiversity. Work. Pap. Urban Lang. Literacies 2011, 67, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, E. The Two-Step Flow of Communication: An Up-to-Date Report on an Hypothesis. Public Opin. Q. 1957, 21, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, L. Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language. Appl. Linguist. 2017, 39, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohamed Jamrus, M.H.; Razali, A.B. Using Self-Assessment as a Tool for English Language Learning. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2019, 12, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, K. Mainland Chinese Students’ Shifting Perceptions of Chinese-English Code-Mixing in Macao. Int. J. Soc. Cult. Lang. 2019, 7, 106–117. [Google Scholar]

- Hüseyin, H.; Üniversitesi, A.; Bilimler, S. Questionnaries and Interviews in Educational Researches. Atatürk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 2009, 13/1, 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Krumm, H.J.; Jenkins, E.M. Kinder und Ihre Sprachen—Lebendige Mehrsprachigkeit: Sprachenporträts; Eviva: Vienna, Austria, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kasap, S. The Language Portraits and Multilingualism Research; University of Gjakova: Gjakova, Kosovo, 2021; pp. 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaja, P.; Pitkänen-Huhta, A. ALR Special Issue: Visual Methods in Applied Language Studies. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 2018, 9, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kusters, A.; De Meulder, M. Language Portraits: Investigating Embodied Multilingual and Multimodal Repertoires. FQS 2019, 20, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, G.L. Portraits of Plurilingualism in a French International School in Toronto: Exploring the Role of Visual Methods to Access Students’ Representations of Their Linguistically Diverse Identities. CJAL 2014, 17, 5177. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, R.; Nichols, S. The Multiple Resources of Refugee Students: A Language Portrait Inquiry. Int. J. Multiling. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, C.T.; Duarte, J.; Günther-van der Meij, M. “Red Is the Colour of the Heart”: Making Young Children’s Multilingualism Visible through Language Portraits. Lang. Educ. 2020, 35, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, R.V. “Then Suddenly I Spoke a Lot of Spanish”—Changing Linguistic Practices and Heritage Language from Adolescents’ Points of View. Int. Multiling. Res. J. 2020, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galante, A. Pedagogical Translanguaging in a Multilingual English Program in Canada: Student and Teacher Perspectives of Challenges. System 2020, 92, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, S. Visual Silence in the Language Portrait: Analysing Young People’s Representations of Their Linguistic Repertoires. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2022, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.-Y.; Lin, P.-H.; Chien, W.-C. Children’s Digital Art Ability Training System Based on AI-Assisted Learning: A Case Study of Drawing Color Perception. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Altun, M. The Use of Drawing in Language Teaching and Learning. J. Educ. Instr. Stud. World 2015, 5, 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Swales, J. General Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, B. School Language Profiles: Valorizing Linguistic Resources in Heteroglossic Situations in South Africa. Lang. Educ. 2010, 24, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M.; Mathison, S. Researching Children’s Experiences; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaheri, B. Feature Extraction and Image Classification Using OpenCV. Available online: https://www.dominodatalab.com/blog/feature-extraction-and-image-classification-using-deep-neural-networks (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Tibaut, K.; Lipavic Oštir, A. »Jaz Sem 16 % Madžar in 50 % Slovenec in 80 % Anglež.«Jezikovni Portreti Petošolcev Na Narodnostno Mešanih Območjih. Rev. Za Elem. Izobr. 2021, 14, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzdok, D.; Altman, N.; Krzywinski, M. Statistics versus Machine Learning. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, A.; Marcus Wallenburg, C. Dealing with Supply Chain Risks. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2012, 42, 887–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agbo, G.C.; Agbo, P.A. The Role of Computer Vision in the Development of Knowledge-Based Systems for Teaching and Learning of English Language Education. ACCENTS Trans. Image Process. Comput. Vis. 2020, 6, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiippala, T. Combining Computer Vision and Multimodal Analysis: A Case Study of Layout Symmetry in Bilingual Inflight Magazines. In Building Bridges for Multimodal Research: International Perspectives on Theories and Practices of Multimodal Analysis; Wildfeuer, J., Ed.; Peter Lang: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 289–307. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, M.A. The Think-Aloud Controversy in Second Language Research; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, J.; Zegwaard, K.E. Methodologies, Methods and Ethical Considerations for Conducting Research in Work-Integrated Learning. Int. J. Work-Integr. Learn. 2018, 19, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fazlji, A. Examining the Language Ideologies of Highly Proficient English Speakers in Sweden; Stockholms Universitet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, M.; Bojanowski, P.; Joulin, A.; Douze, M. Deep Clustering for Unsupervised Learning of Visual Features. In Proceedings of the ECCV; Cornell University: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.; Seraj, R.; Islam, S.M.S. The K-Means Algorithm: A Comprehensive Survey and Performance Evaluation. Electronics 2020, 9, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, K.T.; Taha, M.C. Rethinking the Digital Divide: Smartphones as Translanguaging Tools among Middle Eastern Refugees in New Jersey. Ann. Anthropol. Pract. 2019, 43, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, M.A.K.; Hasan, R. Language, Context, and Text: Aspects of Language in a Social-Semiotic Perspective; Christie, F., Ed.; Oxford University Press, Cop: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Widdowson, H.G. Explorations in Applied Linguistics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, R.A. Beyond the English Learner Label: Recognizing the Richness of Bi/Multilingual Students’ Linguistic Repertoires. Read. Teach. 2018, 71, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makihara, M. Chapter 10 Heterogeneity in Linguistic Practice, Competence and Ideology: Language and Community on Easter Island. Nativ. Speak. Concept 2009, 249–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauring, J.; Selmer, J. Openness to Diversity, Trust and Conflict in Multicultural Organizations. J. Manag. Organ. 2012, 18, 1870–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauring, J.; Paunova, M.; Butler, C.L. Openness to Language and Value Diversity Fosters Multicultural Team Creativity and Performance. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2015, 2015, 13090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschini, R. Sprachbiographien Randständiger Sprecher. In Biographie und Interkulturalität. Diskurs und Lebenspraxis; Stauffenburg Verlag: Tubingen, Germany, 2001; pp. 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- King, L. The Impact of Multilingualism on Global Education and Language Learning; Cambridge Assessment English: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanawaty, N.; Malini, N.; Wiasti, M.; Bagus, I. Language and Social Identity: Language Choice and Language Attitude of Diaspora Communities in Bali. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2021, 28, 979–992. [Google Scholar]

- Et-Bozkurt, T.; Yağmur, K. Family Language Policy among Second- and Third-Generation Turkish Parents in Melbourne, Australia. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2022, 43, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, B. Regaining a Place from Which to Speak and to Be Heard: In Search of a Response to the “Violence of Voicelessness”. Stellenbosch Pap. Linguist. PLUS 2016, 46, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, W.A.; Gu, M.M.; Hult, F.M. Translanguaging for Intercultural Communication in International Higher Education: Transcending English as a Lingua Franca. Int. J. Multiling. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Computer Vision in Education: Powering the Future of Learning. Available online: https://www.analyticsinsight.net/computer-vision-in-education-powering-the-future-of-learning/ (accessed on 2 December 2022).

| OpenCV + K-Means | SPSS | |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Machine learning algorithm | Statistical software 29 |

| Input | Pictures | Numeric data |

| Output | Prediction | Inference |

| Example | Detect and classify objects | Find probability |

| Robustness | High | Low |

| Pseudonym | Gender | Age | Ethno-Linguistic Identity | Region of Origin | School Type Background |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U1 | Female | 20 | Mandarin Chinese | Heilongjiang | Dominantly Chinese |

| U2 | Female | 19 | Cantonese Chinese | Guangdong | Dominantly Chinese |

| U3 | Female | 18 | Macanese | Macao | Chinese, English, and Portuguese |

| U4 | Female | 18 | Cantonese Chinese | Macao | Chinese and English |

| P1 | Female | 23 | Cantonese Chinese | Macao | Chinese and English |

| P2 | Female | 24 | Cantonese Chinese | Macao | Chinese and English |

| P3 | Female | 27 | Macanese | Macao | Chinese and Portuguese |

| P4 | Male | 25 | Macanese | Macao | Chinese, English, and Portuguese |

| Participant | Duration of LPs in Task 1 | Duration of LPs in Task 2 | Duration of Interviews |

|---|---|---|---|

| U3 | 20 min | 35 min | 25 min |

| P3 | 18 min | 14 min | 25 min |

| P4 | 15 min | 25 min | 25 min |

| Cantonese | Mandarin | Portuguese | English | Other: ______ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope | High | Low | High | Medium | |

| Access | High | Low | High | Medium |

| Cantonese | Mandarin | Portuguese | English | Other: ______ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope | High | Low | Low | Medium | |

| Access | Medium | High | High | Medium |

| Cantonese | Mandarin | Portuguese | English | Other: ______ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope | High | Low | Low | High | |

| Access | High | Low | Low | High |

| Cantonese | Mandarin | Portuguese | English | Other: ______ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope | High | Low | Low | High | Medium |

| Access | High | Low | High | Medium | Medium |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mu, S.; Li, A.; Shen, L.; Han, L.; Wen, Z. Linguistic Repertoires Embodied and Digitalized: A Computer-Vision-Aided Analysis of the Language Portraits by Multilingual Youth. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032194

Mu S, Li A, Shen L, Han L, Wen Z. Linguistic Repertoires Embodied and Digitalized: A Computer-Vision-Aided Analysis of the Language Portraits by Multilingual Youth. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032194

Chicago/Turabian StyleMu, Siqing, Aoxuan (Douglas) Li, Lu Shen, Lili Han, and Zhisheng (Edward) Wen. 2023. "Linguistic Repertoires Embodied and Digitalized: A Computer-Vision-Aided Analysis of the Language Portraits by Multilingual Youth" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032194

APA StyleMu, S., Li, A., Shen, L., Han, L., & Wen, Z. (2023). Linguistic Repertoires Embodied and Digitalized: A Computer-Vision-Aided Analysis of the Language Portraits by Multilingual Youth. Sustainability, 15(3), 2194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032194

_Wen.jpg)