Abstract

The purchase of food from family farming in public institutions in Brazil was boosted by the implementation of the public call modality. The National School Feeding Program—PNAE— and the Food Acquisition Program—PAA— are world references in terms of purchasing food from family farming. However, hindrances are still observed regarding the participation of small farmers in public purchase of food, reducing their participation and scope of the food products available. Using a cross-sectional approach, this study analyzed food from family farming purchased by federal institutes of education located at the northeast region of Brazil to characterize the profile of family farmers participating on public calls, identify the food required and verify the processing level of food present into these documents. The data obtained indicate that family farmers supply mainly in natura or minimally processed foods, especially fruits. Meat and meat products were not present and processed foods, such as cheese, were not purchased extensively from family farmers by federal institutes, even when farmers were grouped into cooperatives and associations. Failure to comply with sanitary requirements required in the public call process was the main reason for the non-homologation of some food from family farming. The data found in this study show that despite the advances that allowed the purchase of food from family farming in public educational institutions, it is necessary to find ways to increase the diversity of food. Investing in improving structural conditions would be a way to increase the quality and diversity of food provided by family farming in public institutions, contributing to the environmental, social, and health dimensions of sustainability.

1. Introduction

Family farmers and rural family entrepreneurs are those who perform their activities predominantly with family labor. To be considered a family farmer in Brazil, the land area of the farm must measure up to four fiscal modules (5 to 110 hectares) and must have a minimum percentage of family income originate from activities performed in their establishment or enterprise [1,2,3].

In Brazil, family farming only occupies 23% of the total area of agricultural establishments despite representing 77% of them. Moreover, some of those farmers still access the land in the condition of “settler without definitive title” in a temporary or precarious way, indicating a reflex of the historical marginalization of that group, derived from unequal distribution of opportunities and knowledge amidst the process of agricultural industrialization and the new technologies employed in the field [4,5].

Corporate agriculture companies are often developed based on wage labor, with a focus on monoculture, exportation, and production of foodstuffs for the food industry, particularly soybean, beef cattle, and sugar [6]. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) highlights that this hegemonic sector is one of the main groups responsible for environmental and health impacts [7]. Such impacts are also highlighted by the discussion of the global syndemic, which indicates synergy between malnutrition and climate change and ratifies the urgency in enacting actions that consider food and health in their most diverse aspects [8]. FAO appoints that the family farmers have the potential to mitigate the main global issues mentioned in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), revealing the importance of studies and the development of policies that promote their expansion [9]. The access to institutional markets by family farmers is an opportunity to encourage short food marketing chains, contributing to an increase in farmers’ income and enabling the supply of local food to public institutions such as school restaurants.

In Brazil, two important policies are mentioned as the main institutional tools to promote the insertion of family farming in public purchases: the Food Purchase Program (Programa de Aquisição de Alimentos—PAA) and the National Program of School Feeding (Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar—PNAE). These programs are recognized worldwide for their roles in promoting the Human Right to Adequate Food (HRAF) and Nutrition and Food Safety (NFS) [10,11].

In 2009, purchasing food from family farming became mandatory in Brazilian PNAE, and public schools must use at least 30% of the amount of money spent on food to purchase directly from family farmers [12]. It is noteworthy that the success of such insertion also led to the creation of another modality of public purchase called PAA-Institutional Purchase (PAA-Compra Institucional—PAA-CI), which refers to the mandatory investment (also 30%) of resources toward the purchase of foods from family farming in public organizations [13,14,15].

In Brazil, the Federal Institutes of Education—“institutions of higher, basic, and professional education, multicurricular and multicampus, specialized in the supply of professional and technological education in the different teaching modalities”—acquire foods from family farming both via the PNAE and PAA-CI, as the process fits the guidelines of both norms [16]. PNAE finances from the National Fund of Education Development—FNDE— only R$0.36 for student per day, corresponding to 0.07 USD.

In Rio Grande do Norte State, the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology is distributed across 21 units featuring about 44 thousand enrollments, with most (53%) students being pardo (an official nomenclature of the Brazilian census meaning brown-skinned) and having per capita family income of up to half of the minimum wage (62.2%) [17]. In this context, the role of schools and collective feeding is capable of uniting aspects related to the environment, social well-being, and health.

Concerning the improvement of family farming in the public purchases, the benefits include the activation and valorization of the local economy and producers, the increase in the variety and number of healthy foods, the reconnection with a genuine food culture, and the insertion of productions with lower use of conventional agricultural inputs [18,19]. Nonetheless, school feeding has a positive association with lower consumption of highly processed foods, as well as proves able to improve the quality of student diet, particularly of those living in areas at high risk of social vulnerability, helping reduce diet inadequacies associated with social unevenness, for example [20,21].

Brazilian school feeding norms incorporated the recommendations of the Brazilian Dietary Guide and of the Nutrient Profile Model of the Pan-American Heath Organization (PAHO), emphasizing the level of food processing, production origin, and critical nutrients as matters to be regulated [22]. However, there is still much to advance regarding the regulation of producers, their types, and modes of production inherent to the processes of food purchase, particularly regarding family farming. These occur not only due to technical-administrative issues of the centers executing bidding processes but also spawn from the very specifications that rule the public policies that include family farmers, in addition to issues inherent to the form of organization and governmental investment towards that group [23]. It can be noted, thus, that the very existence of the law that ensures its spaces, per se, is not enough for the development and permanence of those policies, entailing the need to follow the issues involved with their work [24].

The present research, performed in Federal Institutes of Education of Rio Grande do Norte state (FIRN) located in the northeast region of Brazil, intends to answer three main questions: (1) What is the characterization of the family farmers who applied to provide food for the Federal Institutes of Education in the period studied? (2) What kind of foods from family farming were available to be provided to the FIRN? (3) What is the processing level of food enabled to be provided by these farmers?

2. Methodology

The present cross-sectional study of descriptive and exploratory character was performed between February and July 2021, assessing the notices of public call process (PC) for the purchase of food from family farming to school feeding of Federal Institutes of Education of Rio Grande do Norte state (FIRN). Rio Grande do Norte state (RN) is in the northeast region of Brazil, featuring 167 municipalities with a total area of 52,809,601 km2 and about 3,560,903 inhabitants [25]. Until the period studied, the RN had 20 IFRN Campi with integrated technical education distributed in all regions of the State, with 11,900 students matriculating. The school meals offered through the PNAE at the FIRN were aimed at technical high school students aged between 14 and 20 years.

The present research did not require the approval of the Committee of Ethics and Research as it dealt with the analysis of documents in the public domain [26].

2.1. Definition of the Study Sample

This study is part of a project entitled ‘Food for Students at Federal Institutes of Education in Rio Grande do Norte and its Interface with Sustainable Nutrition’. We used the same sampling carried out for the project and collected the information contained in PC for purchases of food from family farming on the selected campuses.

Sample size was calculated via the software R and the sampling package, with the use of function sample.size.prop, which returns the possible sample sizes considering the sampling error and the level of confidence. This study considered a confidence interval of 95% and sampling error of 0.18, within the universe of the campuses (20 campuses) that offers integrated technical courses to the students, with a final sampling size of 15 campuses to the present study [27,28].

Figure 1 shows the 15 institutions selected by proportionate simple stratified sampling in their respective immediate regions. In this method, the populational units are proportionally distributed in each stratum and the method was chosen due to the presence of different size strata. When the sample size did not provide whole results, the value was rounded up. The final sample was given by the union of samples selected in each stratum.

Figure 1.

IFRN campuses selected according to the stratified sampling by immediate regions, Rio Grande do Norte/Brazil.

The decision of structuring sampling by immediate regions was based on Resolution no. 6/2020 by FNDE, which rules the purchases by the PNAE, which consider the location of the food-production headquarters in relation to the campus, with preference for local suppliers in detriment of those located in immediate and intermediate regions [22].

According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística—IBGE) [29], immediate regions are those that have urban centers as reference points to meet the immediate needs of their population, while intermediate regions are responsible for the organization of the territory and flow between units of the federation and immediate regions. In RN, the 167 municipalities are distributed into 11 immediate geographic regions grouped in three intermediate regions. This geographic space holds 20 FIRN campuses with an integrated technical education that served about 11,900 students in 2020.

2.2. Analysis of the Published and Homologated/Adjudicated Public Call Notices

To observe which foodstuffs were able to be purchased by FIRN both the opening notices and the homologation/adjudication of PC were assessed, concerning the year of 2020, 15 campuses were selected through proportionate simple stratified sampling.

In Brazilian public purchase procurement processes, the public notice is the convening act of the bidding, aiming to establish rules for the realization of the process, being a mandatory compliance by both the administration and the bidders. All participants in the public calls were family farmers, as this type of purchase is part of a policy to encourage family farming in Brazil. In general terms, the external stages consist of opening (publication of the public notice), qualification, classification or judgment, homologation, and adjudication. This research analyzed the two latest steps. The homologation and adjudication stages correspond, respectively, to the control of the legality of the bidding procedure (non-approval may occur in cases of non-compliance with the steps designated in the public notice) and the attribution of the object of the bidding to the winner [30].

The food products were grouped according to the categories presented in the IQ COSAN Manual [31] and Resolution no. 6/2020 [22] (Table 1). The evaluation considered the sum of foods present in the public notices both via PNAE and via PAA-CI for a total of four public notices analyzed (two of opening and two of homologation/adjudication), each containing all campuses of the sample.

Table 1.

Food groups considered for the analysis of foods to be purchased via public call in 2020 at the FIRN campuses, Rio Grande do Norte State, Brazil.

2.2.1. Characterization of the Food Suppliers

To characterize the family farming suppliers of the 15 FIRN campuses, the homologated/adjudicated public notices were analyzed regarding the licensing of the supplier as described in Resolution no. 6/2020 [22]. The follow topics were investigated: (1) The identification of the qualification of the suppliers, as “Formal Group”, “Informal Group” or “Individual supplier”—nomenclature utilized to define how the family farmers are organized for their production activity [22]; (2) The formal group organization (association or cooperative) [32]; (3) The type of production (organic, agroecological, or conventional) [33,34,35], by searching in a collaborative map of the Collaborator Center in School Feeding and Nutrition (Centro Colaborador em Alimentação e Nutrição Escolar—CECANE) [36] and in the National Registry of Organic Products [37]; (4) The production headquarters of the farmers by immediate region [29]; (5) The immediate region of supply [29]; (6) The variety of products supplied (see Table 1).

2.2.2. Assessment of the Homologation/Adjudication of Foods Listed in the Public Calls

The homologation/adjudication analysis considered all foods present in the opening public notice and homologated both paths of food acquisition (PNAE and PAA-CI). To access the quantity of food, we considered the number of foods homologated. Later, the difference between the number of foods and food groups present in the homologated public notice in relation to the opening one was observed. Complementarily, the justifications for non-homologation were also grouped according to the descriptions contained in the public notices themselves.

2.2.3. Assessment of the Processing Level of the Foods

The quality of feeding that is offered to the students considered the guidelines imposed by Resolution no. 6/2020 [22] based on the analysis of all products presented in the homologated/adjudicated public notices. They were assessed considering their extension and purpose of processing (in natura or minimally processed, processed, ultra-processed, and processed culinary ingredients) according to the NOVA classification [38].

2.3. Data Analysis

The data were tabulated and analyzed using the software Microsoft® Excel® 2013 version 15.0, with the results shown as absolute and relative frequency.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Food Suppliers

The characterization of the family farmers is showed in Table 2. In 2020, 32 proponents to supply foods to the campuses that were part of this study won the notices of public calls of FIRN, with 50% of the farmers qualified as “formal groups,” which were organized into cooperatives (56.25%) and associations (43.75%). Regarding the type of production of all family farmers assessed, only two declared being producers of agroecological base, while “individual suppliers” was the only one among the qualifications surveyed for which no information was found.

Table 2.

Characterization of the family farmers by supplier qualification, public calls for acquisition of foodstuffs from family farming, 2020, FIRN, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

The “formal groups” were scattered across 63.64% of the immediate regions of RN, contrasting with “informal” and “individual suppliers,” with headquarters in three of the 11 regions studied. It was also observed that the immediate regions with the higher concentration of winning proponents benefitted a larger number of institutions. Only three of the 12 immediate regions did not have any supplier farmer with production headquarters at those sites.

Concerning food groups, farmers in “formal groups” accounted for the supply of a greater variety of foods, with “milk and dairy” distributed only across these types of farmers. “Fruits” and “products of limited supply” were part of the food groups supplied by most of the family farmers irrespective of their qualification.

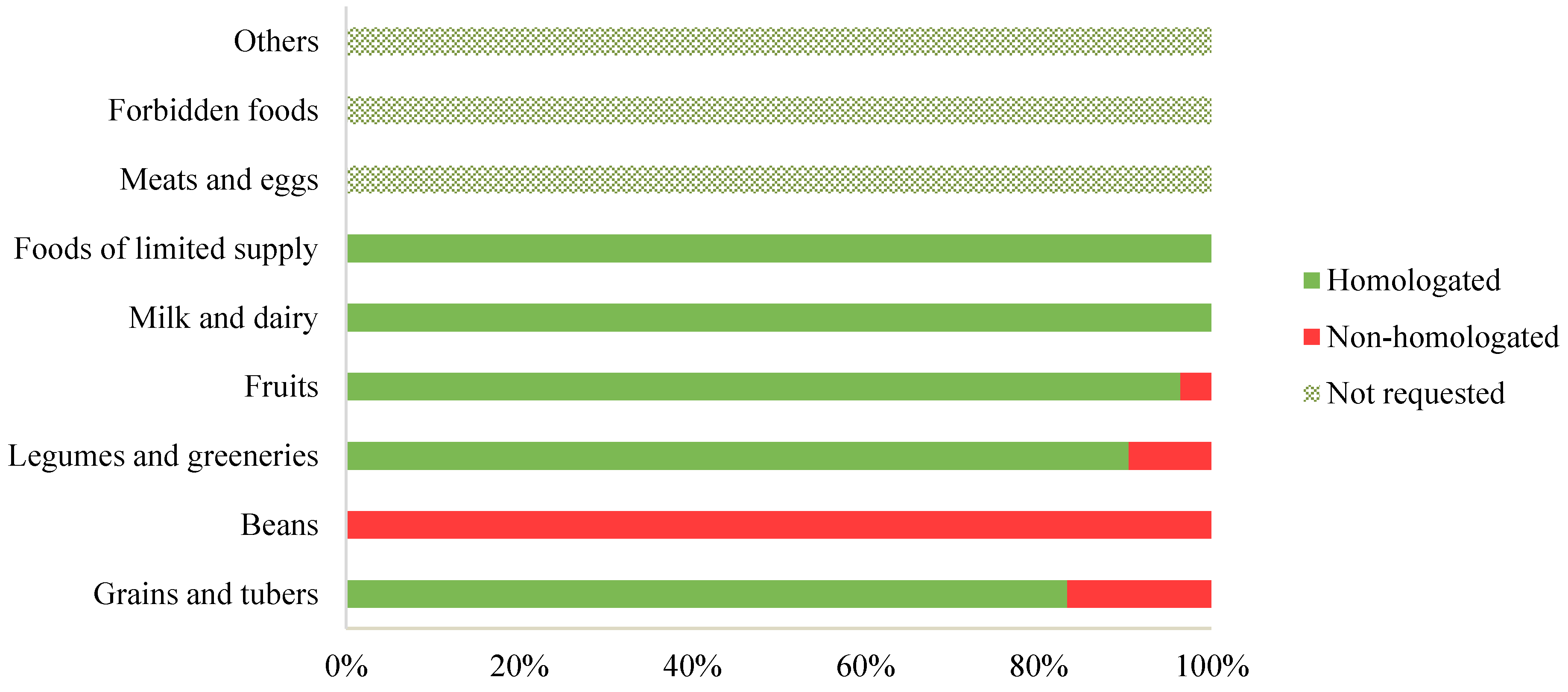

3.2. Assessment of the Homologation/Adjudication of Foods

Some institutions failed to homologate some of the products requested as described in the opening public notice. Table 3 shows the variety of homologated foods on the analyzed public calls by food groups.

Table 3.

Variety of foods presented on the analyzed public calls by homologated status, FIRN, RN, 2020.

In all, 94.8% of the foods were homologated. Over two thirds of those foods were in the groups of fruits (67.5%) and foods of limited supply (14.5%) (e.g., cakes without filling/icing and dairy beverages). It is worth pointing out that most foods of limited supply were concentrated in the PAA-CI public notices.

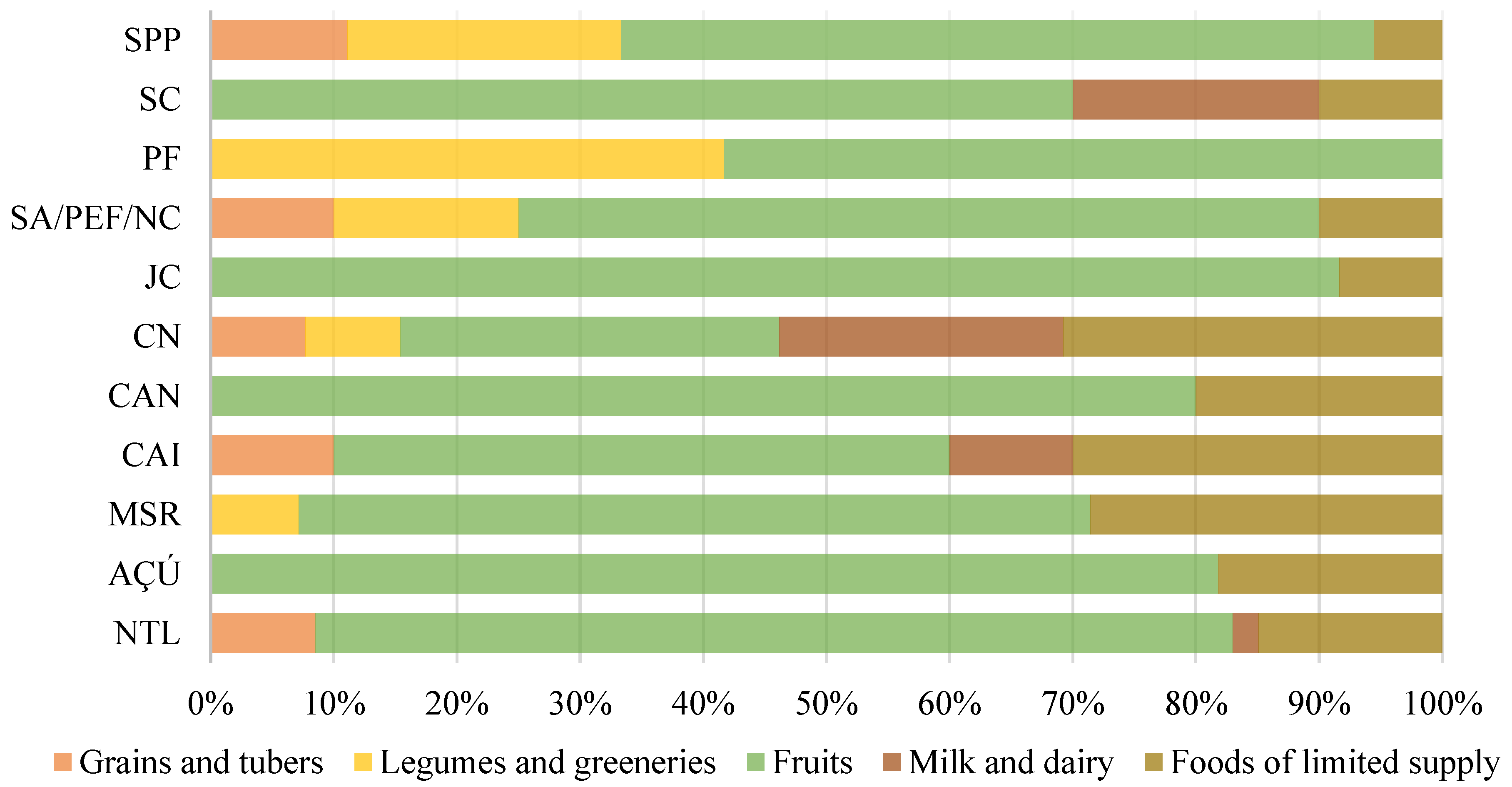

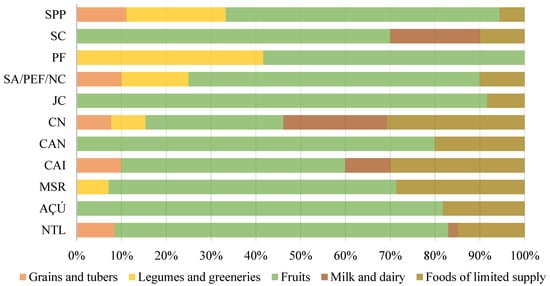

Most regions (54.5%) requested between three and four different food groups. The “milk and dairy” group was the least requested one, present only in Currais Novos, Santa Cruz, Caicó, and Natal, followed by “grains and tubers” and “legumes and greeneries,” requested in only a third of the regions. Some regions, despite hosting farmers who supplied a greater variety of food groups, did not request them (such as Natal and Açu) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Food groups homologated/adjudicated by immediate region, via public call, 2020FIRN, RN, Brazil. Legend: Natal (NTL); Mossoró (MSR); Caicó (CAI); Canguaretama (CAN); Currais Novos (CN); João Câmara (JC); Santo Antônio-Passa e Fica-Nova Cruz (SA/PEF/NC); Pau dos Ferros (PF); Santa Cruz (SC); São Paulo do Potengi (SPP).

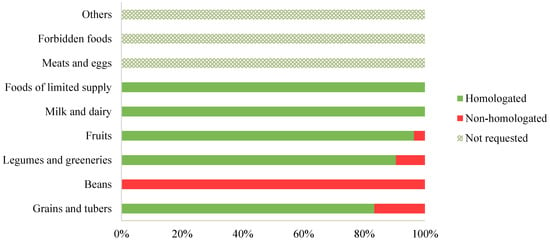

No food in the groups “Meats and eggs,” “Forbidden foods,” or “Others” was requested in the opening public notices. The group “Beans” was present in the opening public notice, in a single institution, but was not homologated (Figure 3). Accordingly, as the described on the homologated/adjudicated public calls, some groups could not be homologated due to two principal reasons: (1) The absence of proposals by the farmers to supply the products contained in the public notice; (2) The non-present food sample for quality control analysis, a mandatory requirement for participation in the public procurement process in Brazil. It is worth pointing out that some of those non-homologated foods are part of the food culture of the state, such as green beans and red rice.

Figure 3.

Status of the food groups regarding their requesting in the notices of public calls, 2020, FIRN, RN, Brazil.

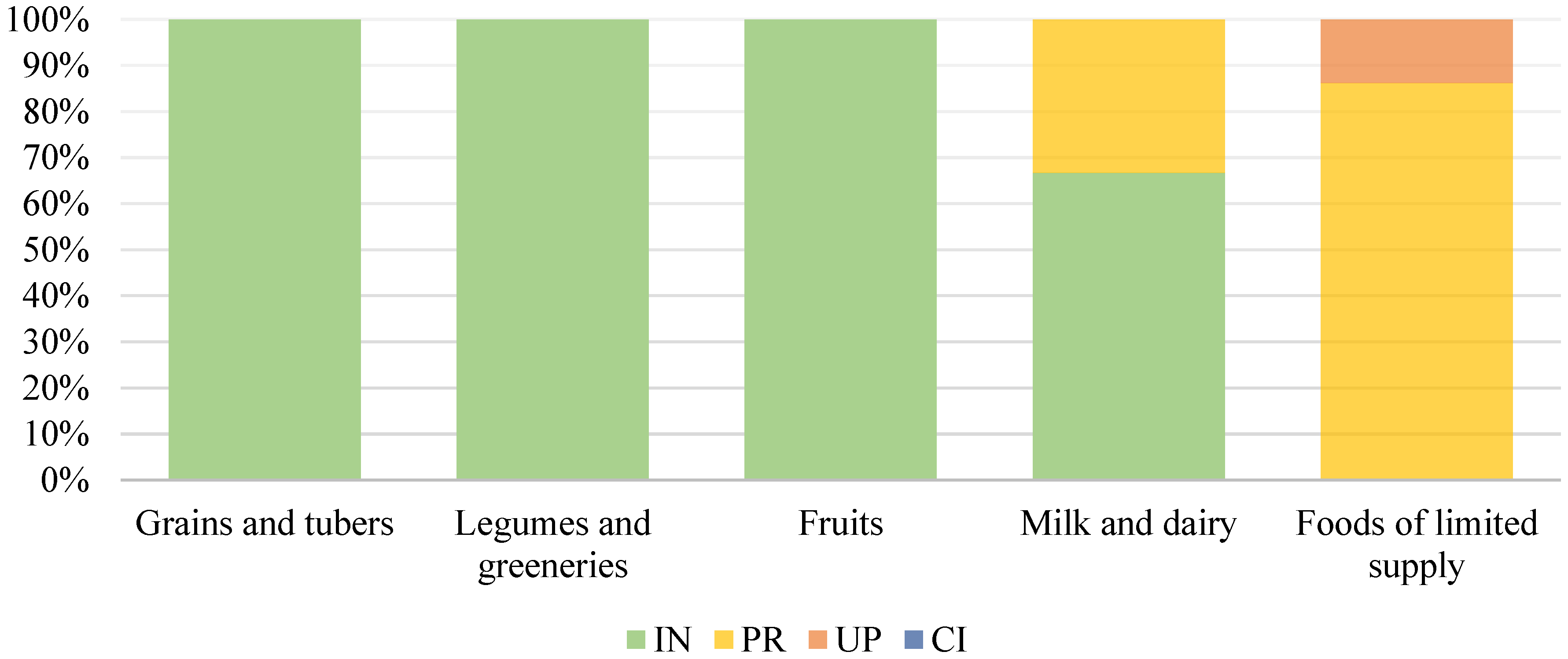

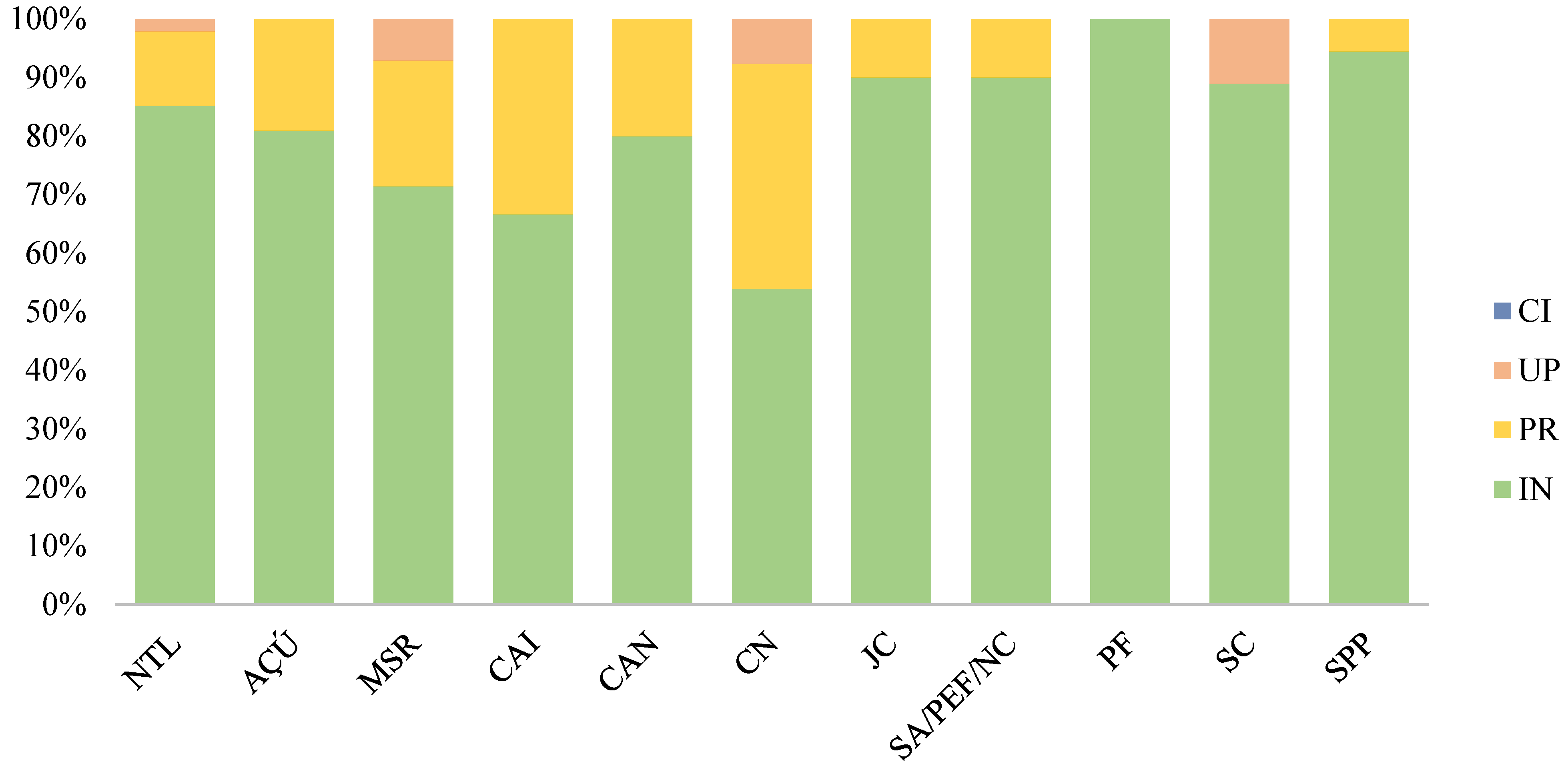

3.3. Assessment of the Processing Level of the Foods

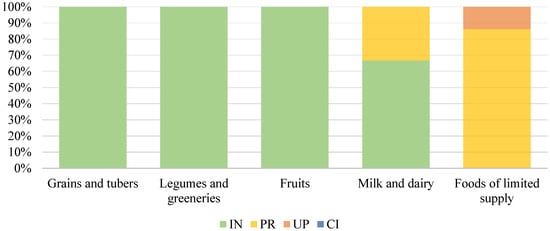

Most of the foods coming from the public calls were classified as in natura or minimally processed (83.06%). On a smaller scale, the homologation of processed (14.75%) and ultra-processed foods (2.19%) was found, with no request of “culinary ingredients” in the notices of public calls. When analyzed by food groups, it could be seen that 100% the groups of “grains and tubers” and horticultural items were classified as in natura or minimally processed, as shown in Figure 4. In the group of dairies, despite exhibiting a greater concentration of foods in natura or minimally processed, about a third was classified as processed. In contrast, it was observed that “foods of limited supply” were within the groups with the highest level of processing, most being processed (e.g., cakes with no filling/icing) (86.2%) and, at a lower level, ultra-processed (e.g., dairy beverages) (13.8%).

Figure 4.

Level of processing of the homologated/adjudicated foodstuffs by food group, public call, 2020, FIRN, RN, Brazil. Legend: In natura or minimally processed (IN); Processed (PR); Ultra-processed (UP); Culinary ingredients (CI).

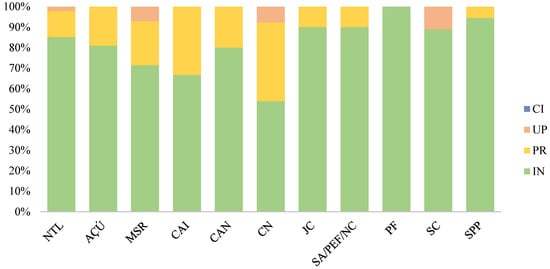

Analyzing Figure 2, Figure 4 and Figure 5, it is possible to observe that the percentages of processed and ultra-processed foods identified in the notices of the immediate regions studied may have reflected the presence of products that need greater processing for their manufacture. Regional cheeses (e.g., Brazilian traditional butter and curd cheeses), contained in the group “milk and dairy,” and bakery products (such as cassava, corn, and egg cakes) and dairy beverages present in the “foods of limited supply” are examples of that.

Figure 5.

Level of processing of the homologated/adjudicated foodstuffs by immediate region, public call, 2020, FIRN, RN, Brazil. Legend: In natura or minimally processed (IN); Processed (PR); Ultra-Processed (UP); Culinary ingredients (CI); Natal (NTL); Mossoró (MSR); Caicó (CAI); Canguaretama (CAN); Currais Novos (CN); João Câmara (JC); Santo Antônio-Passa e Fica-Nova Cruz (SA/PEF/NC); Pau dos Ferros (PF); Santa Cruz (SC); São Paulo do Potengi (SPP).

Individually, Currais Novos (46%) and Caicó (33%) were the regions that most requested foods with a greater level of processing. The other regions requested under 30% of processed and ultra-processed foods in the public calls (Figure 5).

4. Discussion

The results of this research show that half of the farmers who were winners of the notices of public calls are members of cooperatives, associations, or union entities, some characterized as “informal groups”. Those qualified as “formal groups” supplied a larger number of immediate regions and a larger variety of food groups, with the group “milk and dairy” being supplied only by those farmers. Aquino et al. [39] report that nearly 30% of the family farmers in RN State have no association with class entities, a factor that may limit the construction of infrastructure for economic production, technological innovation, and access to markets.

Despite the specificities reported in public notices regarding the type of production of preference for the public calls to corroborate the principles of the norms of PNAE and PAA-CI [22,40], the present study shows that few producers were identified as organic and agroecological cultivation. Triches, Schabarum and Giombelli [41] also showed the scarcity of purchase of foods cultivated that way when investigating the school feeding in the municipalities of the state of Paraná, despite the 30% reached in food purchases from family farming as required by Law 11,947/2009. The superficial understanding of the subject matter by the actors involved, besides the lack of incentive, public policies, and certification are the main causes for the failure to establish those foods in school feeding [42,43].

The selection criteria both of PNAE and PAA-CI consider the proximity of food suppliers with the requesting institution [22,40]. Knowing that some immediate regions of the study were represented by more than one campus, the delivery logistics may have been an unfavorable aspect for the requisition of certain food groups, even if there were suppliers in the same immediate region as the headquarters of the campuses. Such specifications of selection, when expressed in the public notices, enable the insertion of family farmers into different regions of the state, particularly when mapping producers and their available foods in the region of the bidding process.

Another issue is the possibility of processing or industrialization of the raw material of the family farmers via hiring or partnership of services through persons or legal entities that may not even be part of the PNAE or PAA [40,44]. Moreover, allowing for the expansion of destination areas of their products and favoring farmers who live in drought areas, through the extension of shelf life, the variability of foods supplied may also increase.

It was observed that the farmers who supply “milk and dairy” were mostly located in the regions known as Seridó Potiguar, represented in the present study by the immediate regions of Caicó and Currais Novos. Seridó, a region of semiarid climate with little rainfall, has dairy farming as one of its main rural economic activities. As it is inserted in a drought environment, temporary crops and fruticulture activities are performed according to the specifications of each municipality, as well as regional climate conditions [45], which may justify the low availability of food groups supplied by farmers of the immediate region of Currais Novos, for example.

The development indexes and the efficiency of economic investments into rural development policies also can interfere with the success of the family farmers’ activities and productivity. It is known that areas with a lower human development municipal index, and with a higher percentage of extremely poor habitants show a higher probability to access programs of rural development. The lower economic investment and the changes in regulation to more restrictive conditions to sell some products (e.g., processed and animal-origin products) for those farmers may be the reason for the tendency of reduction in variability of foods purchased by this program over the years. Observing these points in the family industry is important not just for the promotion of value aggregation and economic movement, but principally for the promotion of food and nutrition security [46,47].

Regarding the foods that feature in the homologated public notices, most were classified as in natura or minimally processed, particularly the group of “fruits,” which was the most supplied by the farmers assessed and the most requested in the notices of public calls of IFRN, proportionally. According to Resolution no. 6/2020 [22], the purchases for school feeding must prioritize foods in natura or minimally processed, with only 25% of the funds going towards purchasing processed and ultra-processed foods and processed culinary ingredients. The menus also must provide a minimum number of fruits and vegetables during the week. The results show the concern of the institutions assessed by following the guidelines of the norms in effect, even by not requesting “forbidden foods”. Despite this, we noticed that a few regions requested more than 25% of these types of regulated foods.

The positive influence brought in school feeding by family farming is evident regarding the increase in variety and supply of horticulture, in natura, or minimally processed products when compared with ultra-processed ones [19,48,49,50,51]. However, at the same time, this characteristic proves positive in promoting the health of students, as well as leading to positive changes in their consumption pattern [52], the quality of those foods and the way they are produced, as well as the lack of variety produced (especially for foods of local sociobiodiversity) and sold by those producers also carries other important discussions. Food purchases for public institutions can work as a promoter of sustainable development goals when they support local commerce, improving not only the quality of food for users of public services, but also generating income for small local farmers.

It was observed that some foods of different groups were not homologated, with failure to provide a sample for analysis and the absence of proposals by the farmers to supply the products contained in the public notice being listed as reasons in the public notices analyzed. In parallel, other food groups were not even requested in a public notice. Factors such as lack of resources, structure, labor, and price that are not aligned with the local reality are examples that keep producers away from public bids. The organization of farmers is cited as one of the strategies to bring together farmers and current legislations, as well as allowing for better infrastructure for production and commercialization [53].

Nutritionists and others involved with school management play a key role in managing public food procurement in the school environment. In addition to price surveys in local markets to allow for fair participation of family farmers in the bidding process, the menus must also be planned to consider the local products available, as well as the production practices by the farmer, considering frequency and seasonality in view of the different dynamics among large, medium, and small supply centers [23]. The public notices also need to describe the specifications of the products as a preventative measure in food purchases to ensure proper hygienic-sanitary conditions, even to allow for impartial analysis of food samples that are part of one of the steps of the food procurement processes [54].

The low variety of foods and the solicitation of beneficiated or ready products (e.g., cakes and fruit pulp) can also reveal the reality of some studied institutions, knowning that a lot of them do not have the physical structure to produce their meals. In addition, the total or partial FNDE’s recourse used on the public calls in FIRN, is destinated to the snacks, which could explain, in part, the variety of food groups found on the results of the present study. In situations such as these, it is necessary that the nutritionist adheres to the conditions of their workplace while also maintaining a commitment to the provision of adequate and healthy food [22,55].

Studies have revealed that although family farming is a significant part in a number of agricultural establishments, it lacks in area of hectares (many are not even proprietors of their cultivation land), in structures, and incentives that allow their development and expansion as producers, and shows to be vulnerable in matters of soil and climate (such as the droughts in certain regions of the northeast, as RN), while, in contrast, large retail and corporate producers are strengthened [4,23,39]. In addition to political-administrative issues of the sectors involved, some products require sanitary and normative quality standards and criteria of specific verification that end up hindering the inclusion of those farmers in such a commercial sector [56].

In Brazil, much is discussed regarding the existing norms for sanitary regulation and its excluding character as it has little room for the practices developed by many family farmers, particularly for the commercialization of animal-origin products. Issues such as those also impact their participation in formal markets and the scope of foods provided to such markets. The result would be centralizing the procurement of products around large industrial centers, raising questions of whether the focus is sanitary control of foods or the creation of market reserve for those large centers [57,58].

Just like beef and poultry, fish were also not found in the public notices assessed in the present study. Leite [59], when analyzing the insertion of fish into the PNAE in the coastal regions of the Brazilian Northeast reported the low prevalence of this product in school meals, particularly coming from family farming, probably as consequence of the lack of qualified producers, the low acceptance of fish by students, and its high price.

The Brazilian Northeast, predominantly semiarid, hosts 25% of the national aquiculture production. In family pisciculture, it was noted that excess production is marketed to middlemen (independent dealers that connect producers and buyers) or directly to final consumers in street markets. Modernizing the logistics of fish flow and processing, as well as the formation of cooperatives and permanent qualification of fishermen are issues that can help the development of this area; thus, allowing for openings in various markets [60].

Studies have shown that meats and processed meat products purchased by public education institutions are rarely local in origin [61,62]. However, this group of foods still features within the scope of supply of family farming in the public calls, also with special attention to processed foods [49], signaling that there is potential for the distribution and production of different food groups by family farmers.

To Helfand and Taylor [63], policies that help build human capital will keep being indispensable to reduce rural poverty in developing countries. Far beyond land distribution, policies that aim to impact production equity and efficiency must focus on ensuring access to the productivity gains experienced by large networks.

Concerning the management of planting, a vast number of horticulture products are being produced in the country with excessive use of pesticides and grown based on biotechnology, the latter also used to produce a variety of ultra-processed foods [18,64,65]. The literature already appoints health and environmental problems associated with the use of the technologies [66,67,68]. Regarding the production of family farmers, studies show that the use of agrochemicals is still present in their cultivation. Even realizing the associated dangers, farmers face difficulties in the transition to agroecological production due to insufficient financial return and the production practice of neighboring establishments, for example [42,69,70].

As for the acquisition processes, the insertion of organics seems to be correlated with greater population density, the number of producing establishments within that area, in addition to the active role of local/regional administration and the interest of the requesting institutions themselves. That confirms the importance of sustainable action by interested parties regarding the development, institution, and maintenance of policies that support this type of production and its producers [71].

Within this context, the fulfilling and strengthening, as well as the investigation of procurement and conditions of the production of foods with agroecological and organic bases become even more urgent; seen as the classification of the level of processing by itself is not able to describe all the nuances involving the production chain. The collective feeding sector must consider the supply of safe foods not only from the nutritional standpoint, but also from the biological and sanitary standpoints [55].

Furthermore, other issues must also be seen regarding the presence of processed foods produced and sold by family farming. In the present study, cakes with no filling and cheeses of the regional culture were identified in the public notices, some included in the group “products of limited supply,” considered the second most requested and supplied group among the regions analyzed. It is important to highlight that the insertion of foodstuffs that respect the culture and traditions of the people is also part of the principles of healthy eating [18,22].

Soares et al. [49] observed that in addition to family farmers supplying fruits and vegetables, processed foods were also significant in public calls in all regions of the country. It is believed that the inclusion of food products with more processing may enable the economic and social reintegration of producers within commercial networks.

Assuming the purchase of food from family farming based on the degree of processing as a unique and restrictive criterion can also generate and/or signal tension between what you want to buy, who produces it, and which food culture this product belongs to. Campos et al. [72] highlight the importance of monitoring the realities of the family farmers and their production methods, as well as the potentialities of the region during the public call; the incompatibility between these points can stimulate deviations “as the supply of foods that are not part of the production of the farmers or organization, that attend the requisites required to participate of the calls”. It is important that regulations exist on the purchase and supply of certain foods, visualizing the impacts of the consumption of those with a higher level of processing on the health of adolescents [73], the target audience of school meals of the federal education institutions in this study, as well as social and environmental issues [18], since the request of dairy beverages was noted in some of the regions analyzed in the present research.

The present study contributes to the literature by elucidating practical details of the process of public bidding for the acquisition of food from family farming in Brazil. The challenge to be highlighted by the results of the study is that to acquire a wide variety of foods from family farming, governments must ensure that small producers have the structure and capacity to offer the food requested from schools and other public institutions. It is key to encourage public purchases of food from family farming to be completely successful.

As the main shortcoming, we can highlight that our study presents the reality of only a single federative unit in the Brazilian Northeast. The difficulty for the identification of agroecological and organic production also stands out, with the lack of access to documents and certificates presented by the family farmers contributing to that. All data in this topic were found via the Collaborative Map of CECANE—that are units of reference and support created by federal higher education institutions to develop actions of interest of the PNAE. Although the map if considerably filled out by the farmers themselves, it has facilitated the identification of the objects in analysis.

Moreover, the menus provided to students was not assessed, requiring new studies that jointly analyze all purchase modalities to better diagnose the implementation of food and nutrition public policies in the present context, also involving research with family farmers participating in the public calls. As it was an evaluation of the steps prior to the creation of the menus, the care in comparing or adapting the present study with research that assesses the purchase of foods and the supply of meals is emphasized.

5. Conclusions

The results showed that family farmers participate in procurement programs by supplying mainly fruits, with the production of the organic and agroecological base still little explored and expressed. Nearly half of the food groups analyzed were not requested or homologated, the latter issue was the result of both technical-sanitary matters and for the lack of farmers interested in supplying the product requested by the institutions. Additionally, in natura or minimally processed foods were observed in the public notices; in contrast, limited participation of family farming was noted regarding the supply of processed foods.

Observing the percentage of non-homologation of foods, we highlight that more articulations and organizational fostering for strengthening the participation of these farmers in public biddings is important work for federal institutions of education for opening opportunities for this population.

It is believed that the findings of this study contribute to the understanding of the dynamics of Brazilian family farmers and form their insertion in the institutional market, possibly facilitating the maintenance and/or dissemination of their role in the context of public procurement, with emphasis on the importance of food and nutrition public policies and of family farming as social, environmental, nutritional, and economic protection nets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.R.G.d.S., D.V., P.M.R. and L.M.J.S. Methodology: S.R.G.d.S., D.V., P.M.R., L.M.J.S., H.I.F.d.N., J.C.N. and A.H.M.d.S.J. Formal analysis: S.R.G.d.S., H.I.F.d.N., J.C.N. and A.H.M.d.S.J. Investigation: S.R.G.d.S. Writing—Original Draft: S.R.G.d.S., D.V., P.M.R. and L.M.J.S. Writing—Review and Editing: S.R.G.d.S., D.V., P.M.R., L.M.J.S., H.I.F.d.N. and A.H.M.d.S.J. Visualization: S.R.G.d.S. and L.M.J.S. Supervision: L.M.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Partial financial support was received from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-Brasil-CAPES-Financial Code 001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The present study did not require the approval of the Committee of Ethics and Research as it dealt with the analysis of documents in the public domain.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Rio Grande do Norte, the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte and the UFRN Pro-Rector for Research (PROPESQ) for their support through the Scientific Initiation Program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brasil LEI No 11.326, DE 24 DE JULHO DE 2006. Estabelece as Diretrizes Para a Formulação Da Política Nacional Da Agricultura Familiar e Empreendimentos Familiares Rurais. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2006/lei/l11326.htm (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Brasil Decreto No 84.685, de 6 de Maio de 1980. Regulamento a Lei No 6.746, de 10 de Dezembro de 1979, Que Trata Do Imposto Sobre a Propriedade Territorial Rural—ITR e Dá Outras Providências. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/1980-1989/d84685.htm (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Brasil Lei No 6.746, de 10 de Dezembro de 1979. Altera o Disposto Nos Arts. 49 e 50 Da Lei No 4.504, de 30 de Novembro de 1964 (Estatuto Da Terra), e Dá Outras Providências. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/1970-1979/l6746.htm (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Censo Agropecuário 2017: Resultados Definitivos; Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE): Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2019; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Rambo, J.R.; Tarsitano, M.A.A.; Laforga, G. Agricultura Familiar No Brasil, Conceito Em Construção: Trajetória de Lutas, História Pujante. Rev. CIÊNCIAS AGROAMBIENTAIS 2016, 14, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, L.A.C. Caracterização Do Sistema Agropecuário Dentro Da Agricultura Familiar Como Subsídio de Políticas Públicas. Available online: https://repositorio.ufrn.br/bitstream/123456789/17187/1/LiviaACD_DISSERT.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD); UNICEF; WFP; World Health Organization (WHO). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020: Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.J.; Baker, P.I.; Bogard, J.R.; Brinsden, H.; Calvillo, A.; De Schutter, O.; Devarajan, R.; et al. The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission Report. Lancet 2019, 393, 791–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; FAO. United Nations Decade of Family Farming 2019-2028. The Future of Family Farming in the Context of the 2030 Agenda; Rome, 2019; ISBN 9789251315033. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca4672en/ca4672en.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Bocchi, C.P.; Magalhães, É.D.S.; Rahal, L.; Gentil, P.; Gonçalves, R. de S. A Década Da Nutrição, a Política de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional e as Compras Públicas Da Agricultura Familiar No Brasil. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2019, 43, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil MEDIDA PROVISÓRIA No 1.061, DE 9 DE AGOSTO DE 2021. Institui o Programa Auxílio Brasil e o Programa Alimenta Brasil, e Dá Outras Providências. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/medida-provisoria-n-1.061-de-9-de-agosto-de-2021-337251007 (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- Brasil. Presidência da República. Casa Civil. Subchefia de Assuntos Jurídicos. LEI No 11.947, DE 16 DE JUNHO DE 2009. Dispõe Sobre o Atendimento Da Alimentação Escolar e Do Programa Dinheiro Direto Na Escola Aos Alunos Da Educação Básica; Altera as Leis Nos 10.880, de 9 de Junho de 2004, 11.273, de 6 de Fevereiro de 2006, 11.507, de 20 de Julho de 2007; Revoga Dispositivos Da Medida Provisória No 2.178-36, de 24 de Agosto de 2001, e a Lei No 8.913, de 12 de Julho de 1994; e Dá Outras Providências. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2007-2010/2009/Lei/L11947.htm (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Centro de Excelencia contra a Fome (WFP). Modalidades de Compras Públicas de Alimentos Da Agricultura Familiar No Brasil II: Série Políticas Sociais de Alimentaçao; WFP: Brasília, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil Decreto No 8473, de 22 de Junho de 2015. Estabelece, No Âmbito Da Administração Pública Federal, o Percentual Mínimo Destinado à Aquisição de Gêneros Alimentícios de Agricultores Familiares e Suas Organizações, Empreendedores Familiares Rurais e Demais Be. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2015/decreto/D8473.htm (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Lopes, I.D.; Basso, D. Cadeias Agroalimentares Curtas e o Mercado de Alimentação Escolar Na Rede Municipal de Ijuí, RS. INTERAÇÕES 2019, 20, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil Lei No 11.829, de 29 de Dezembro de 2008. Institui a Rede Federal de Educação Profissional, Científica e Tecnológica, Cria Os Institutos Federais de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia, e Dá Outras Providências. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2007-2010/2008/Lei/L11892.htm (accessed on 2 October 2021).

- Brasil; Governo Federal; Ministério da Educação (MEC); Plataforma Nilo Peçanha (PNP) Rede Federal de Educaçao Profissional, Científica e Tecnológica. PNP 2020 (Ano Base 2019). Instituições. Cursos, Matrículas, Ingressantes, Concluintes, Vagas e Inscritos Por Instituição e Unidade de Ensino. Available online: http://plataformanilopecanha.mec.gov.br/2020.html (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Brasil Ministério da Saúde; Secretaria de Atençao à Saúde; Departamento de Atençao Básica. Guia Alimentar Para a Populaçao Brasileira, 2nd ed; Brasil Ministério da Saúde; Secretaria de Atençao à Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2014; ISBN 978-85-334-2176-9. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, P.; Davó-Blanes, M.C.; Martinelli, S.S.; Melgarejo, L.; Cavalli, S.B. The Effect of New Purchase Criteria on Food Procurement for the Brazilian School Feeding Program. Appetite 2017, 108, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, B.M.A.; Da, A.; Moreira, C.; Do Carmo, A.S.; Dos Santos, L.C.; Horta, P.M. A Higher Number of School Meals Is Associated with a Less-Processed Diet. J. Pediatr. Rio J. 2018, 94, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, P.M.; do Carmo, A.S.; Verly Junior, E.; Santos, L.C. dos Consuming School Meals Improves Brazilian Children’s Diets According to Their Social Vulnerability Risk. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2714–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil Resolução No 06, de 08 de Maio de 2020. Dispõe Sobre o Atendimento Da Alimentação Escolar Aos Alunos Da Educação Básica No Âmbito Do Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar—PNAE. Available online: https://www.fnde.gov.br/index.php/acesso-a-informacao/institucional/legislacao/item/13511-resolução-no-6,-de-08-de-maio-de-2020 (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Chaves, V.M.; Galvão, L.; Pinheiro, B.; Alexandra, R.; De Araújo, A.D.; Barbosa, J.; Eneas, P.; Bezerra, R.; Cristine, M.; Jacob, M. Challenges to Balance Food Demand and Supply: Analysis of PNAE Execution in One Semiarid Region of Brazil. Desenvolv. e meio Ambient. 2020, 55, 470–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swensson, L.F.J.; Tartanac, F. Public Food Procurement for Sustainable Diets and Food Systems: The Role of the Regulatory Framework. Glob. Food Sec. 2020, 25, 100366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE Rio Grande Do Norte|Cidades e Estados|IBGE. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/rn.html (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- IFRN. Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Rio Grande do Norte. Portal IFRN. Administração. Licitações. Licitações. Chamada Pública. Available online: https://portal.ifrn.edu.br/acessoainformacao/licitacoes-e-contratos/licitacoes (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Tillé, Y.; Matei, A. Sampling: Survey Sampling. R Package Version 2.8. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=sampling (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- IBGE. Divisão Regional Do Brasil Em Regiões Geográficas Imediatas e Regiões Geográficas Intermediárias 2017; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2017; ISBN 978-85-240-4418-2. [Google Scholar]

- Serviço Brasileiro de Apoio às Micro e Pequenas Empresas (Sebrae). Compras Públicas: Um Bom Negócio Para a Sua Empresa; Sebrae, Ed.; Serviço Brasileiro de Apoio às Micro e Pequenas Empresas (Sebrae): Brasília, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fundo Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Educação (FNDE). Índice de Qualidade—IQ COSAN (Manual); FNDE: Brasília, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fundo Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Educação (FNDE). Formação Pela Escola. PNAE: Caderno de Estudos. Available online: https://professor.escoladigital.pr.gov.br/sites/professores/arquivos_restritos/files/documento/2021-09/formacao_escola_pnae.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Brasil Decreto No 7794, de 20 de Agosto de 2012. Institui a Política Nacional de Agroecologia e Produção Orgânica. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2012/decreto/d7794.htm (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Brasil Lei No 10.831, de 23 de Dezembro de 2003. Dispõe Sobre a Agricultura Orgânica e Dá Outras Providências. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/LEIS/2003/L10.831.htm#art1 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Preiss, P.V.; Schneider, S.; Coelho-de-Souza, G. A Contribuição Brasileira à Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional Sustentável, 1 ed.; Editora UFRGS: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2020; ISBN 978-65-5725-006-8. [Google Scholar]

- CECANE/UFRN Mapa de Oferta de Produtos Da Agricultura Familiar No RN. Available online: http://177.20.148.101/views/map (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Ministério da Agricultura Pecuária e Abastecimento (MAPA) Governo Federal. Cadastro Nacional de Produtores Orgânicos. “Clique Aqui Para Acessar o Cadastro Nacional de Produtores Orgânicos”. Available online: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/sustentabilidade/organicos/cadastro-nacional-produtores-organicos (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Jaime, P.; Martins, A.P.; Canella, D.; Louzada, M.; Parra, D.; Ricardo, C.; et al. NOVA. The Star Shines Bright. World Nutr. 2016, 7, 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- De Aquino, J.R.; da Silva, R.M.A.; Nunes, E.M.; Costa, F.B.; Albuquerque, W.F. Agricultura Familiar No Rio Grande Do Norte Segundo O Censo Agropecuário 2017: Perfil E Desafios Para O Desenvolvimento Rural. Rev. Econ. NE 2020, 51, 113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil RESOLUÇÃO No 84, DE 10 DE AGOSTO DE 2020 Dispõe Sobre a Execução Da Modalidade “Compra Institucional”, No Âmbito Do Programa de Aquisição de Alimentos Da Agricultura Familiar—PAA. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-n-84-de-10-de-agosto-de-2020-272236313 (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- Triches, R.M.; Schabarum, J.C.; Giombelli, G.P. Demanda De Produtos Da Agricultura Familiar E Condicionantes Para A Aquisição De Produtos Orgânicos E Agroecológicos Pela Alimentação Escolar No Sudoeste Do Estado Do Paraná. Rev. NERA 2016, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, M.T.M.; de Macedo, A.C.; Antunes Junior, W.F.; Borsatto, R.S.; Souza-Esquerdo, V.F. de Desafios Para a Inserção de Produtos Orgânicos e Agroecológicos Na Alimentação Escolar Em Pequenos e Médios Municípios. Agric. Fam. Pesqui. Formação e Desenvolv. 2021, 15, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, L.D.S.; Rockett, F.C.; Pires, G.C.; Corrêa, R.D.S.; De Oliveira, A.B.A. Alimentos Orgânicos E/Ou Agroecológicos Na Alimentação Escolar Em Municípios Do Rio Grande Do Sul, Brasil. DEMETRA Aliment. Nutr. Saúde 2018, 13, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- FNDE Cartilha II—Agricultura Familiar No PNAE. Available online: https://www.fnde.gov.br/index.php/programas/pnae/pnae-area-gestores/pnae-manuais-cartilhas/item/12065-cartilha-ii-agricultura-familiar-no-pnae (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Silva, V.K. da Mercados Institucionais No Território Do Seridó Potiguar: Potencialidades e Limitações Para Inserção Da Agricultura Familiar. Available online: https://repositorio.ufrn.br/jspui/bitstream/123456789/26003/1/Mercadosinstitucionaisterritório_Silva_2018.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Sambuichi, R.H.R.; de Almeida, A.F.C.; Perin, G.; de Moura, I.F.; Alves, P.S.C. Execução Do Programa de Aquisição de Alimentos Nos Municípios Brasileiros; Instituto de Pesquisa Economica Aplicada—IPEA: Rio de Janeiro, Brazilia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sambuichi, R.H.R.; Perin, G.; Almeida, A.F.C.S.; Alves, P.S.C.; Araújo, D.G.; Câmara, R.D.; Januário, E.S. Diversidade de Produtos Adquiridos Pelo Programa de Aquisição de Alimentos No Brasil e Regiões. Available online: http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/handle/11058/9665 (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- De Amorim, A.L.B.; De Rosso, V.V.; Bandoni, D.H. Acquisition of Family Farm Foods for School Meals: Analysis of Public Procurements within Rural Family Farming Published by the Cities of São Paulo State. Rev. Nutr. 2016, 29, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.; Martinelli, S.S.; Davó-Blanes, M.C.; Fabri, R.K.; Clemente-Gómez, V.; Cavalli, S.B. Government Policy for the Procurement of Food from Local Family Farming in Brazilian Public Institutions. Foods 2021, 10, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.; Martinelli, S.S.; Fabri, R.K.; Veiros, M.B.; Davó-Blanes, M.C.; Cavalli, S.B. Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar Como Promotor de Sistemas Alimentares Locais, Saudáveis e Sustentáveis: Uma Avaliação Da Execução Financeira. Cien. Saude Colet. 2018, 23, 4189–4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, C.R.P.A. The Partnership between the Brazilian School Feeding Program and Family Farming: A Way for Reducing Ultra-Processed Foods in School Meals. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 21, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Master, N.T.L.; Canella, D.S.; Bandoni, D.H. Positive Influence of School Meals on Food Consumption in Brazil. Nutrition 2018, 53, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DevAssis, T.R.P.; de França, A.G.M.; de Coelho, A.M. Agricultura Familiar e Alimentação Escolar: Desafios Para o Acesso Aos Mercados Institucionais Em Três Municípios Mineiros. Rev. Econ. Sociol. Rural 2019, 57, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Aguiar, J.A.; Calil, R.M. Análise e Avaliação Das Especificações Dos Alimentos Contidas Em Editais de Chamadas Públicas Do PNAE. Rev. Vigilância Sanitária em Debate Soc. Ciência Tecnol. 2016, 4, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conselho Federal de Nutricionistas (CFN) Resoluçao No 600, de 25 de Fevereiro de 2018. Dispõe Sobre a Definição Das Áreas de Atuação Do Nutricionista e Suas Atribuições, Indica Parâmetros Numéricos Mínimos de Referência, Por Área de Atuação, Para a Efetividade Dos Serviços Prestados à Sociedade. Available online: https://www.cfn.org.br/wp-content/uploads/resolucoes/Res_600_2018.htm (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Porrua, P.; de Kazama, D.C.S.; Gabriel, C.G.; Rockenbach, G.; Calvo, M.C.M.; Machado, P. de O.; Neves, J. das; Weiss, R. Avaliação Da Gestão Do Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar Sob a Ótica Do Fomento Da Agricultura Familiar. Cad. Saúde Coletiva 2020, 28, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Führ, A.L.; Ancini, N.A.; Triches, R.M. A Agroindústria Familiar e as Regulamentações Sanitárias: Análise Da Aplicabilidade Da Resolução 49/2013 Em Um Município Do Sudoeste Do Paraná. Extensão Rural 2019, 26, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.C.M.; Azevedo, E. Inspeção Sanitária de Produtos de Origem Animal: O Debate Sobre Qualidade de Alimentos No Brasil. Saúde Soc. 2020, 29, e190687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, A.C.S. Diagnóstico Da Inserção Do Pescado No Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar Nos Municípios Costeiros Do Nordeste Brasileiro e o Potencial de Venda Das Reservas Extrativistas Marinhas Federais: Estudo Dos Casos. Available online: https://ava.icmbio.gov.br/mod/data/view.php?d=17&rid=2306 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Ximenes, L.F. Produção De Pescado No Brasil E No Nordeste Brasileiro. Available online: https://www.bnb.gov.br/s482-dspace/bitstream/123456789/649/1/2021_CDS_150.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Hatjiathanassiadou, M.; de Souza, S.R.G.; Nogueira, J.P.; Oliveira, L.d.M.; Strasburg, V.J.; Rolim, P.M.; Seabra, L.M.J. Environmental Impacts of University Restaurant Menus: A Case Study in Brazil. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, J.P.; Hatjiathanassiadou, M.; de Souza, S.R.G.; Strasburg, V.J.; Rolim, P.M.; Seabra, L.M.J. Sustainable Perspective in Public Educational Institutions Restaurants: From Foodstuffs Purchase to Meal Offer. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfand, S.M.; Taylor, M.P.H. The Inverse Relationship between Farm Size and Productivity: Refocusing the Debate. Food Policy 2021, 99, 101977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, A.R.C.; de Rosso, V.V.; Harayashiki, C.A.Y.; Jimenez, P.C.; Castro, Í.B. Global Health Risks from Pesticide Use in Brazil. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-020-0100-3 (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- International Service for the Acquisition of Agrobiotech Applications (ISAAA). Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops in 2018: Biotech Crops Continue to Help Meet the Challenges of Increased Population and Climate Change; ISAAA Brief No 54: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo Frota, M.T.B.; Siqueira, C.E. Pesticides: The Hidden Poisons on Our Table. Cad. Saude Publica 2021, 37, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, H. HÁ ALTERNATIVAS AO USO DOS TRANSGÊNICOS? Novos Estud.–CEBRAP 2007, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valois, A.C.C. Biodiversidade, Biotecnologia e Organismos Transgênicos; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra, I.; Schneider, S. Produção E Consumo De Alimentos: O Papel Das Políticas Públicas Na Relação Entre O Plantar E O Comer. Rev. Faz Ciência 2012, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, E.d.S. Uso de Agrotóxicos Na Produção de Alimentos e Condições de Saúde e Nutrição de Agricultores Familiares. Available online: https://locus.ufv.br//handle/123456789/20389 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Filippini, R.; De Noni, I.; Corsi, S.; Spigarolo, R.; Bocchi, S. Sustainable School Food Procurement: What Factors Do Affect the Introduction and the Increase of Organic Food? Food Policy 2018, 76, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F.M.; de Matos, M.Z.T.A.; Ferreirinha, M.d.L.; Dias, J.F. Compra Institucional: Análise De Chamadas Públicas. Available online: https://proceedings.science/enpssan-2019/papers/compra-institucional--analise-de-chamadas-publicas (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- De Alves, M.A.; Souza, A.d.M.; Barufaldi, L.A.; Tavares, B.M.; Bloch, K.V.; Vasconcelos, F.d.A.G. de Dietary Patterns of Brazilian Adolescents According to Geographic Region: An Analysis of the Study of Cardiovascular Risk in Adolescents (ERICA). Cad. Saude Publica 2019, 35, e00153818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).