Management Control Systems and the Integration of the Sustainable Development Goals into Business Models

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Development Goals and Management Control

2.2. Theoretical Framework

3. Method

4. Results

4.1. Corporate Reporting

4.1.1. From 2050 Sustainability Vision to SDGs in Commitment to Life

“The survey pointed out that, through initiatives related to topics such as carbon, waste, women’s empowerment, education, water, biodiversity, and the Amazon, we contributed directly and indirectly to 16 of the 17 SDGs, except for SDG 14, that treats the oceans.”

“We selected needs of society that we could help to resolve based on our business model. We will use our business and our connections to generate transformation in areas of public interest. (…) We act and monitor results constantly, and now we have organised our actions on three fronts to boost the engagement and mobilisation we generate in these areas. By doing this, we increase the transformational power of our business model.”[31] (p. 41)

4.1.2. Management Controls for Sustainability

“Moreover, the status of the 2020 ambitions and the 2050 Vision is presented to the Executive Committee on a monthly basis and to the Board of Directors every quarter.”[31] (p. 169)

“In 2020, the Board worked closely with the business (…) The approval of the strategic planning, the definition of our sustainability ambitions, part of the Commitment to Life, launched by the group in June, also involved the members of the board. Other items on the agenda were remuneration (…), as well as approval of the organisation’s economic, social and environmental results.”[22] (p. 123)

“The results shown by the calculator, along with other factors, support Natura’s decision to continue or interrupt the product development process, allowing researchers to make more conscious decisions when choosing inputs. The definition of whether or not to develop the product also considers decisions inherent to the business and the availability of resources, among other requirements.”[32] (p. 36)

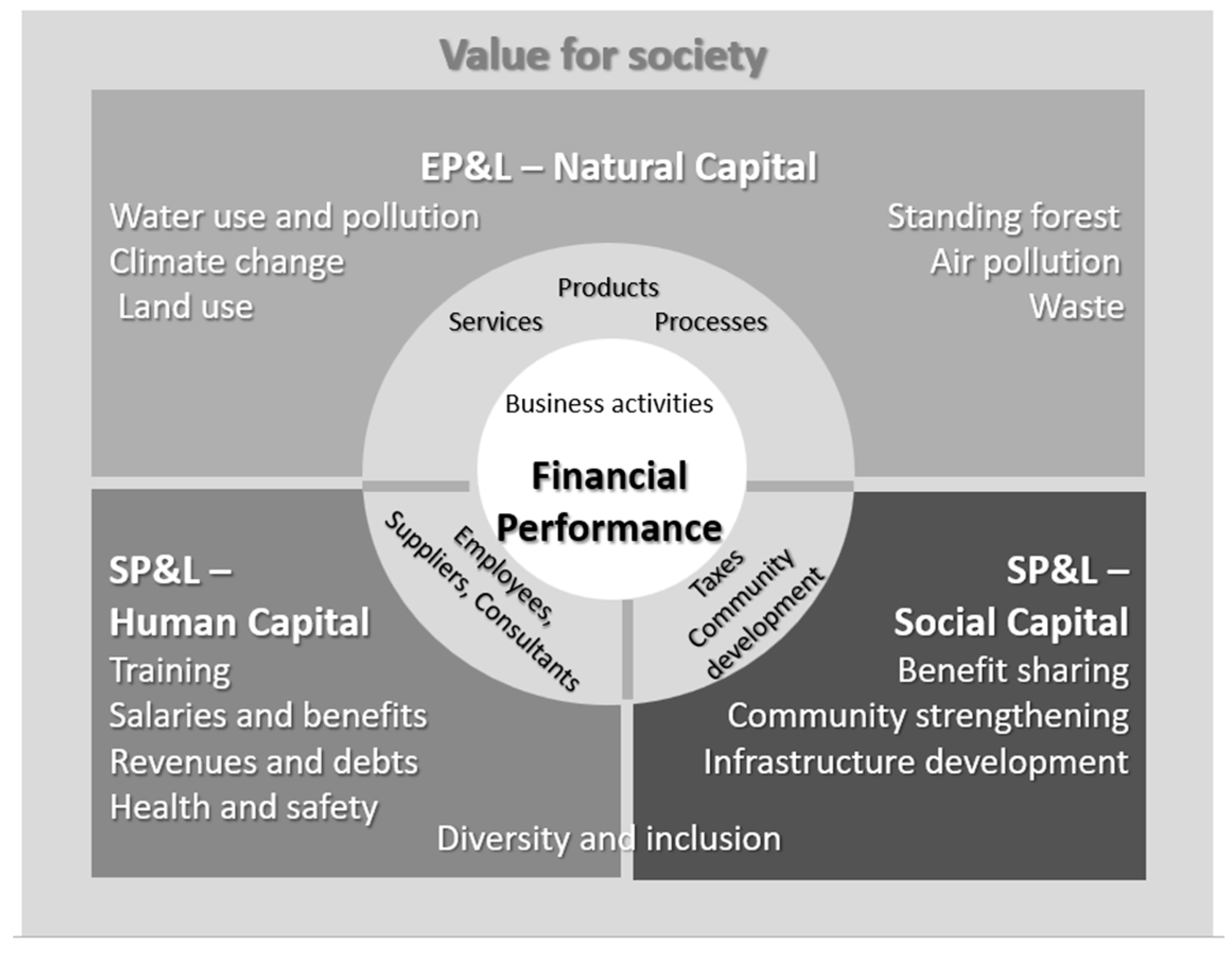

“We recognise the need to develop a disruptive approach that enables the connection of the impact of our actions with business decisions and financial impacts, the IP&L. It innovates by demonstrating in detail that Natura’s value generation goes far beyond its financial indicators, such as revenue and profit. Integrated analysis enables the assessment, for example, of the impact generated on the lives of people who are part of the production chain, in addition to the environmental footprint generated on the planet. (…) The main purpose of the IP&L is to be a tool for shaping business decisions because there is a series of gains and losses to be managed throughout the exercise.”[22] (pp. 65–66)

“A living wage was one of the main references for measuring our contribution to the generation of positive impact in our relations with employees. The parameter considers the amount of salary necessary to cover the basic needs of a family. This includes food, housing, transportation, education, healthcare, payment of taxes, among others. This parameter goes beyond the amount of the minimum salary, establishing a level of better practices in human rights, with the objective of contributing towards the Sustainable Development Goals. In the Natura &Co Commitment to Life (…), we commit to reaching 100% of a living wage for our employees by 2023.”[22] (p. 68)

“One of the main diagnostics of our consultant profile is elaborated based on the Consultant Human Development Index (HDI), a proprietary Natura methodology inspired by the indicators created by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The survey has been in place in Brazil for six years—since 2017, it has been conducted on a biennial basis—and covers three dimensions: health, education and work, with a rating ranging from 0 to 1.”[31] (p. 139)

“The environmental impact is communicated via metrics, formula attributes, packaging and EP&L in the Annual Report and in communications with investors. For consumers, part of the impact is reported on the website and on the Natura APP at the moment of purchase. The full disclosure of the environmental and social impact is still being enhanced to ensure more effective communication.”[22] (p. 61)

“Tracking these [the main socio-environmental challenges] is a responsibility shared by leaders. Commitment to these goals also influences executives’ variable compensation, which encompasses socioenvironmental targets, such as greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.”[31] (p. 169)

“The main indicators [related to waste] monitored by the company are packaging weight (mass), incorporation of post-consumer recycled material, recyclability, the use of renewable materials and carbon emissions. This information also feeds the waste and carbon inventories that are audited externally. Moreover, the carbon emissions associated with packaging contribute to Natura’s total emissions, impacting variable remuneration for the entire company.”[22] (p. 156)

“It is the function of the Executive Committee and the Board of Directors to monitor performance of the Sustainability Vision, in which Natura’s main socioenvironmental and business interests are addressed” [22] (p. 169). Aiming to leverage employees’ potential through engagement in the Natura culture, in 2019, Natura concluded the updating of the Priority Cultural Behaviours, based on the Natura Way of Being and Doing Things [31]. These behaviors, which should be encouraged among all co-workers, are already incorporated into the company’s learning, development, and “team review processes” [31] (p. 132). In 2020, the performance review model was concluded, conducted by a multidisciplinary team based on a diagnosis undertaken with employees: “We reinforced listening processes to understand employees’ needs during these new times and to ensure a positive work experience for everyone.”[22] (p. 102)

“The focus will be on stimulating deliveries that generate value for the employee, for the business and for society, in line with our purpose, our culture and our commitment as a B Corp. Accordingly, the performance review will focus on: designing goals of value for the business; ongoing conversations about deliveries, priority behaviours and development; a proactive stance for individuals and teams; and an integrated system (Workday) to support the process. We developed a communication, training and engagement plan that was prepared especially to support our employees and leaders in this transition to the Natura &Co Latin America Integrated Performance Cycle.”[22] (p. 102)

“We also organised our second Diversity Week, with simultaneous initiatives (…) employing the motto “We need to talk about this”. We disseminated the concept of an inclusive culture, which in 2019 encompassed the sensitisation of senior management and the work force (…). The diversity and inclusion front gained even greater relevance with the definition of Natura’s causes. (…) A specific management area was created to oversee this aspect. This work is supported by the Natura Valuing Diversity Policy, in place since 2016.”[31] (p. 126)

“To reinforce analysis of the effects that significant changes in climate could have on our business, a working group involving the Risk Management and Internal Controls and the Sustainability areas undertook an exercise to map risks and opportunities due to climate change.”[31] (p. 168)

“Our strategic agenda and the commitments we have assumed help us to address emerging risks, which consist of questions that may generate impacts in the long-term, always with an integrated vision of our businesses and social and environmental aspects. The effects of climate change and the loss of social biodiversity are part of the group of risks that could jeopardise the achievement of our business goals, for which Natura had already established scenarios and monitoring processes (…).”[22] (p. 128)

4.2. Key Actors Discourse

5. Discussion

- Defining priorities: Natura mapped 100% of its value chain by identifying the current and probable, positive, and negative activity impacts, seeking through its business models to increase the positive impacts and reduce the negative ones, and defining its materiality matrix which considers and prioritizes the relevant issues.

- Setting goals: Through the 2050 Sustainability Vision, Natura outlines short, medium, and long-term targets and their degree of ambition, and establishes indicators for monitoring and evaluating performance.

- Integration: Natura emphasizes that sustainability is part of the company’s culture and day-to-day, being a responsibility shared by all. The company also believes that only through networking, and sharing knowledge, technologies, resources, and methodologies, is a positive impact possible.

- Reporting and communication: Through its report, Natura communicates the actions for each goal, as well as the progress achieved and the achievement index.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Year | Key Actor | Type | Title | Author | Duration | Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | KM | Webinar | Apresentação de casos brasileiros: Natura | Engenharia de Produção POLI-USP | 16′45″ | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4AWMa70JE2A |

| 2020 | KM | Interview/Podcast | A Sustentabilidade descomplicada da Natura | BHB FOOD | 46′43″ | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e9gT3uhKSBg |

| 2021 | DH | Interview/Podcast | Não dá mais para imaginar uma empresa que não seja ESG|ESG #013 | Exame | 13′47″ | https://exame.com/esg/natura-os-dados-socioambientais-devem-ser-tratados-como-os-financeiros/ |

| 2021 | DH | Interview | CBN Sustentabilidade conversa com Denise Hils diretora global de sustentabilidade da Natura | Rádio CBN | 30′47″ | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZJB0kKOmhZQ |

| 2021 | DH | Interview | O que é sustentabilidade e como nela se inspirar nestes tempos obscuros, para a diretora da Natura | Canal Inconsciente Coletivo | 35′26″ | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1cJNBBENGxc |

| 2021 | KM | Webinar | ESG: um novo horizonte para finanças e negócios, com Keyvan Macedo, Natura &Co | Aberje-Associação Brasileira de Comunicação Empresarial | 13′02″ | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=roU7OTPs2aQ |

| 2022 | DH | Interview | Bate-Papo Ganhadora SDG Pioneers 2022 Brasil | Rede Brasil do Pacto Global | 54′40″ | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xvyjhGvgkBQ |

References

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI); United Nations Global Compact (UNGC); World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). SDG Compass: The Guide for Business Action on the SDGs. 2015. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/3101 (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J. Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: An enabling role for accounting research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crutzen, N.; Zvezdov, D.; Schaltegger, S. Sustainability and management control. Exploring and theorizing control patterns in large European firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 1291–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueg, R.; Radlach, R. Managing Sustainable development with management control systems: A literature review. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.P.; Grubnic, S.; Herzig, C.; Moon, J. Configuring management control systems: Theorizing the integration of strategy and sustainability. Manag. Account. Res. 2012, 23, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arjaliès, D.-L.; Mundy, J. The use of management control systems to manage CSR strategy: A levers of control perspective. Manag. Account. Res. 2013, 24, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmi, T.; Brown, D.A. Management control systems as a package-opportunities, challenges and research directions. Manag. Account. Res. 2008, 19, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, K.; Arru, B. Role and implementation of sustainability management control tools: Critical aspects in the italian context. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2021, 34, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, A.A.; Schrack, D.; Greiling, D. Sustainability reporting and management control—A systematic exploratory literature review. J. Clean. Production. 2020, 276, 122725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, E.; Endrikat, J.; Guenther, T.W. Environmental management control systems: A conceptualization and a review of the empirical evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Banks, G.; Hughes, E. The private sector and the SDGs: The need to move beyond ‘business as usual. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://www.undp.org/ukraine/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development?utm_source=EN&utm_medium=GSR&utm_content=US_UNDP_PaidSearch_Brand_English&utm_campaign=CENTRAL&c_src=CENTRAL&c_src2=GSR&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIvuLS5s_a_AIVBKuWCh2dgg8tEAAYASAAEgLWg_D_BwE (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Agarwal, N.; Gneiting, U.; Mhlanga, R. Raising the Bar: Rethinking the Role of Business in the Sustainable Development Goals; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, A.; Milne, M.J. Sustainability and management control. In Management Control: Theories, Issues, and Performance; Berry, A.J., Broadbent, J., Otley, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2005; pp. 314–337. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, L. Theorising and conceptualising the sustainability control system for effective sustainability management. J. Manag. Control. 2019, 30, 25–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beusch, P.; Frisk, J.E.; Rosén, M.; Dilla, W. Management control for sustainability: Towards integrated systems. Manag. Account. Res. 2022, 54, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jollands, S.; Akroyd, C.; Sawabe, N. Core values as a management control in the construction of “Sustainable Development”. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2015, 12, 127–152. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/QRAM-04-2015-0040/full/html (accessed on 18 December 2022). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- PWC. Creating a Strategy for a Better World How the Sustainable Development Goals Can Provide the Framework for Business to Deliver Progress on Our Global Challenges. 2019. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/sustainability/SDG/sdg-2019.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- PWC. Make it Your Business: Engaging with the Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/sustainability/SDG/SDG%20Research_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Silva, S. Corporate Contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals: An Empirical Analysis Informed by Legitimacy Theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 125962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vionnet, S.; Souza, A.B.; Fernandes, D. Natura Integrated Profit & Loss Accounting 2021—Technical Executive Summary and Insights. 2022. Available online: https://api.mziq.com/mzfilemanager/v2/d/9e61d5ff-4641-4ec3-97a5-3595f938bb75/d8f2cae6-7a86-1d24-8100-62ae5871c7fc?origin=2 (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Natura. Annual Report 2020. Available online: https://static.rede.natura.net/html/sitecf/br/11_2021/relatorio_anual/Annual_Report_Natura_GRI_2020.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- B Lab. About B Corps. Available online: https://bcorporation.net/en-us/certification (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Natura. Natura EP&L. 2016. Available online: https://docplayer.com.br/48833674-Natura-ep-l-ago-2016.html (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Natura. Pense Impacto Positivo Visão de Sustentabilidade 2050. 2014. Available online: https://static.rede.natura.net/html/home/2019/janeiro/home/visao-sustentabilidade-natura-2050-progresso-2014.pdf?iprom_id=visao2050_botao&iprom_name=destaque2_botao_leiamais_23052022&iprom_creative=pdf_leiamais_visaoCurrent URL is invalid2050&iprom_pos=1 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Natura. Programa Carbono Neutro. 2022. Available online: https://static.rede.natura.net/html/2022/natura-programa-carbono-neutro/natura_co2_2022_pt-br.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Natura. Visão de Sustentabilidade 2030 Compromisso com a Vida. 2020. Available online: https://natura.co/press_release_20200615_vision_PT.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Natura &Co. Management by Impact—IP&L (Integrated Profit and Loss), Integrated Management. Available online: https://ri.naturaeco.com/en/gestao-por-impacto-ipl/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Davie, S. An autoethnography of accounting knowledge production: Serendipitous and fortuitous choices for understanding our social world. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2008, 19, 1054–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natura. Relatório Anual 2016. Available online: https://mz-filemanager.s3.amazonaws.com/9e61d5ff-4641-4ec3-97a5-3595f938bb75/relatorios/3f72aebc6b2beecc602c5b443c93b3b52cb5d1c484188ee9a48e2bc21d7030e3/relatorio_anual_2016.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Natura. Annual Report 2019. Available online: https://static.rede.natura.net/html/home/2020/br_09/relatorio-anual-2019/natura_annual_report_2019.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Natura. Relatório Anual 2017. Available online: https://mz-filemanager.s3.amazonaws.com/9e61d5ff-4641-4ec3-97a5-3595f938bb75/relatorioscentral-de-downloads/1528919eefa95cb60bd96c990b5b6ff3acb43e034268ce978835e3523adacd7b/_relatorio_anual_2017_.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Natura. Relatório Anual 2018. Available online: https://mz-filemanager.s3.amazonaws.com/9e61d5ff-4641-4ec3-97a5-3595f938bb75/relatorios/8321a62d4128b42ac9397ce5469a1055cb1d96505b13a691901bf0376249db62/relatorio_anual_natura_2018.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- A Sustentabilidade Descomplicada da Natura. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e9gT3uhKSBg (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- O Que é Sustentabilidade e Como Nela Se Inspirar Nestes Tempos Obscuros, Para a Diretora Da Natura. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1cJNBBENGxc (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- ESG: Um Novo Horizonte Para Finanças e Negócios, Com Keyvan Macedo, Natura&Co. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=roU7OTPs2aQ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Beauty Majors Say Brand-Agnostic Environmental Impact System Will Make Industry More ‘Transparent’ and ‘Comparable’. Available online: https://www.cosmeticsdesign-europe.com/Article/2021/10/07/Henkel-L-Oreal-LVMH-Natura-Co-and-Unilever-talk-environmental-beauty-consortium-goals (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- CBN Sustentabilidade Conversa Com Denise Hils Diretora Global de Sustentabilidade Da Natura. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZJB0kKOmhZQ (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Apresentação de Casos Brasileiros: Natura. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4AWMa70JE2A (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Natura Separa US$ 800 Milhões Para Sustentabilidade Até 2030. Available online: https://exame.com/exame-in/natura-separa-us-800-milhoes-para-sustentabilidade-ate-2030/ (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Bate-Papo Ganhadora SDG Pioneers 2022 Brasil. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xvyjhGvgkBQ (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Para a Natura, Não dá Para Imaginar um Negócio de Sucesso que Não Seja ESG. Available online: https://exame.com/esg/natura-os-dados-socioambientais-devem-ser-tratados-como-os-financeiros/ (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Microsoft, Nike e Natura Formam Consórcio Para Zerar Emissões de Carbono. Available online: https://exame.com/esg/microsoft-nike-e-natura-formam-consorcio-para-zerar-emissoes-de-carbono/ (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Weybrecht, G. The Sustainable MBA: A Business Guide to Sustainability, 2nd ed; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, A.; Wise, R.M.; Hansen, H.; Sams, L. The Sustainable Development Goals: A case study. Mar. Policy 2017, 86, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, L. A Systematic analysis of environmental management systems in SMEs: Possible research directions from a management accounting and control stance. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Florêncio, M.; Oliveira, L.; Oliveira, H.C. Management Control Systems and the Integration of the Sustainable Development Goals into Business Models. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032246

Florêncio M, Oliveira L, Oliveira HC. Management Control Systems and the Integration of the Sustainable Development Goals into Business Models. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032246

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlorêncio, Marina, Lídia Oliveira, and Helena Costa Oliveira. 2023. "Management Control Systems and the Integration of the Sustainable Development Goals into Business Models" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032246

APA StyleFlorêncio, M., Oliveira, L., & Oliveira, H. C. (2023). Management Control Systems and the Integration of the Sustainable Development Goals into Business Models. Sustainability, 15(3), 2246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032246