Environmental Sustainability, Digitalisation, and the Entrepreneurial Perception of Distances as Drivers of SMEs’ Internationalisation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Formulating Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Foundations

2.1.1. The Growth of Firms and the Role of Managers

2.1.2. International Entrepreneurship and the Role of Managerial Perceptions

2.2. Internationalisation of SMEs

2.3. Sustainability, Financial Performance and the Internationalisation of SMEs

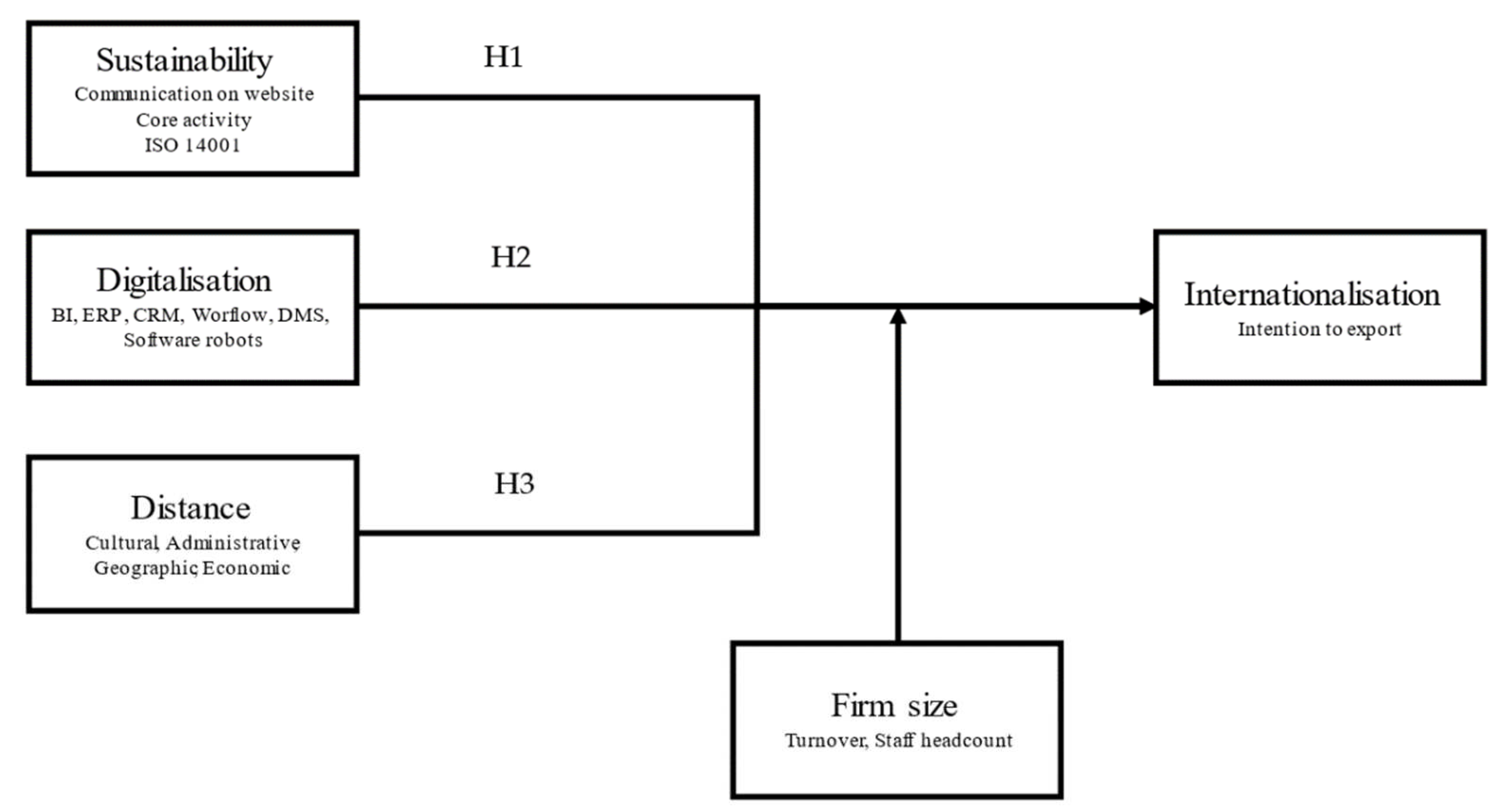

- H1a: SMEs that communicate environmental sustainability on their website are more likely to have a higher intention to export.

- H1b: SMEs that have a core activity related to environmental sustainability are more likely to have a higher intention to export.

- H1c: SMEs that have an ISO 14001 certification are more likely to have a higher intention to export.

2.4. Digital Systems and Internationalisation of SMEs

- H2a: Business Intelligence (BI).

- H2b: Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP).

- H2c: Customer Relationship Management (CRM).

- H2d: Workflow.

- H2e: Document management system.

- H2f: Software robots.

2.5. Entrepreneurial Perception of Distances in the Internationalisation of SMEs

- H3a: Cultural distance.

- H3b: Administrative distance.

- H3c: Geographic distance.

- H3d: Economic distance.

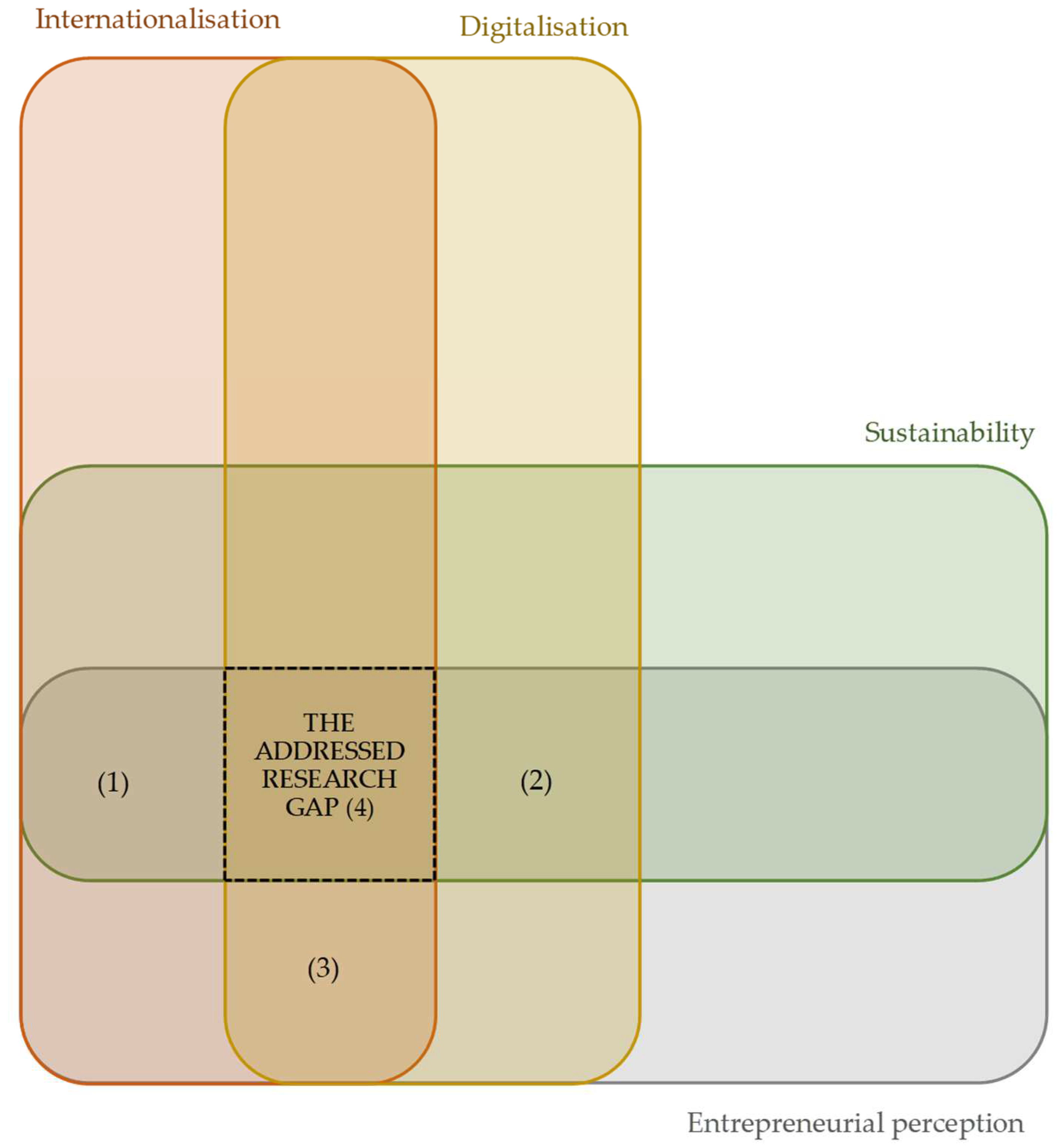

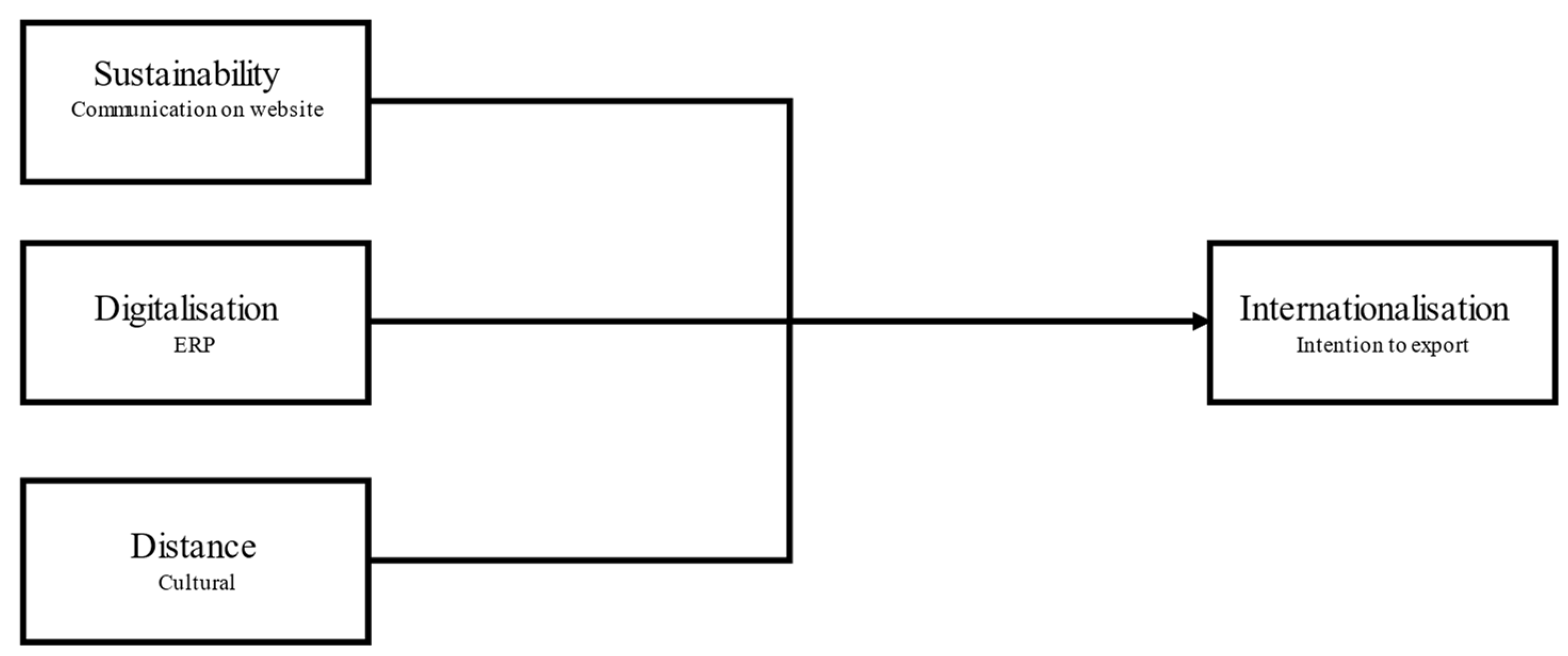

2.6. Research Gap and the Initial Research Model

3. Methodology

3.1. The Query and Sample Characteristics

3.2. Measures and Analysis

4. Results

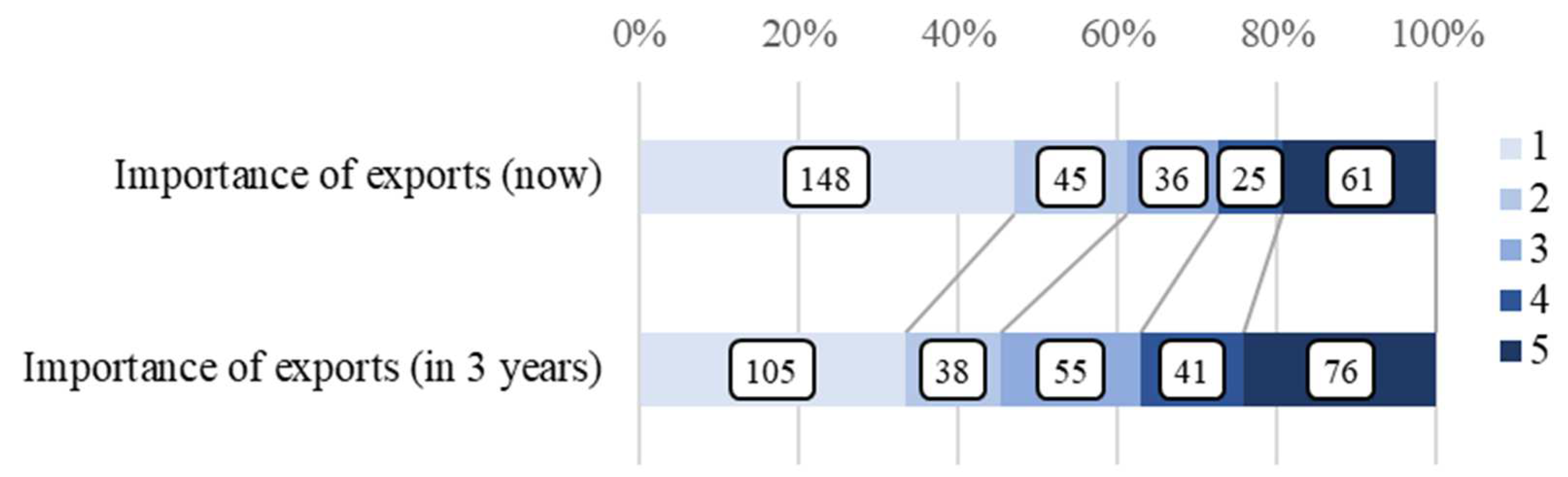

4.1. Internationalisation of SMEs: International Presence and the Importance of Exports

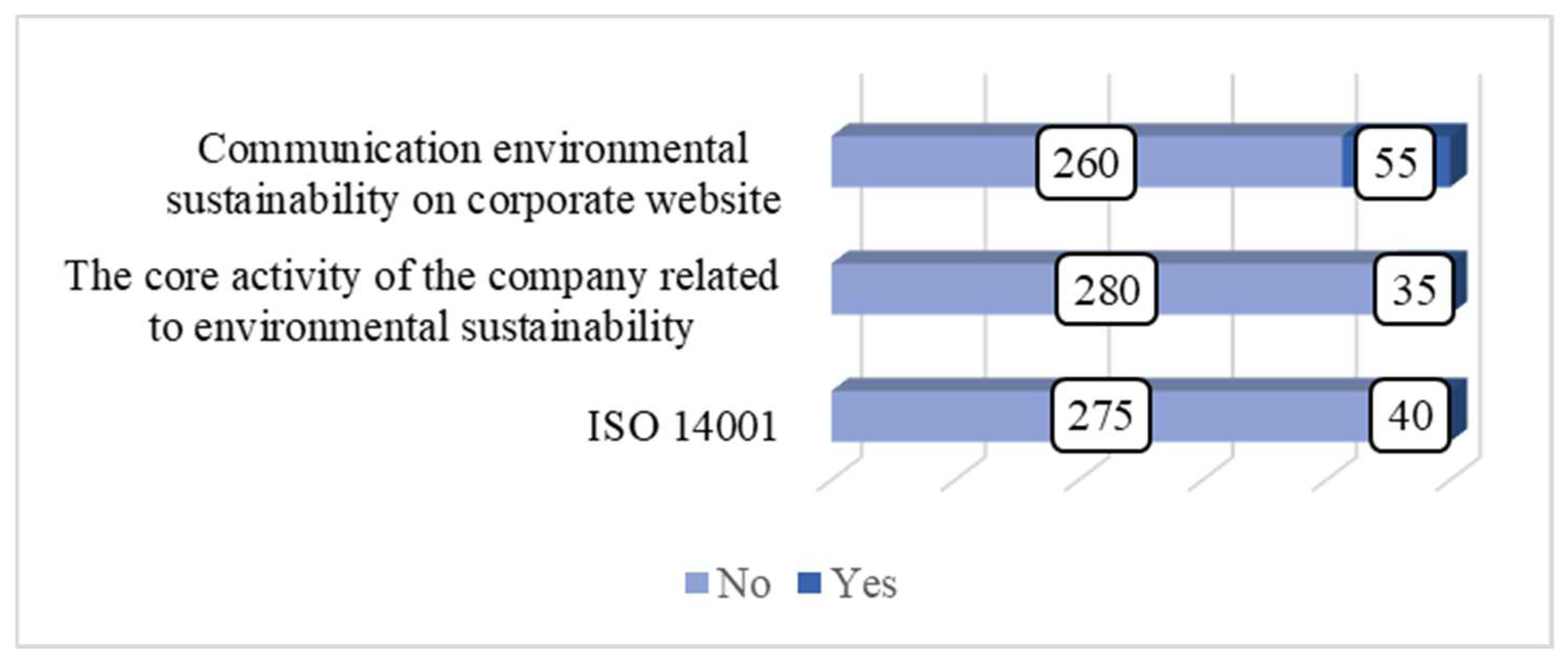

4.2. Sustainability

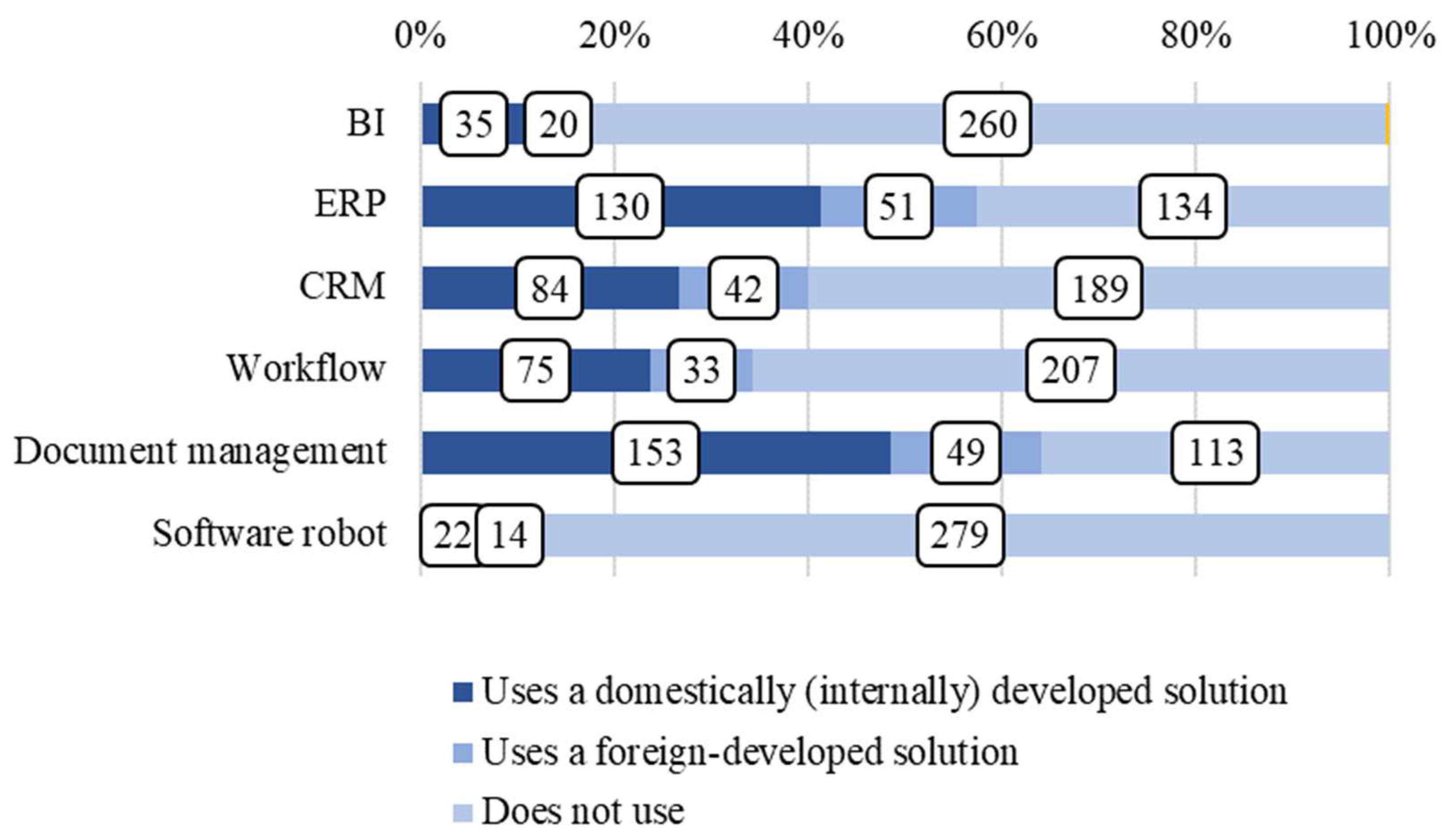

4.3. Digital Solutions

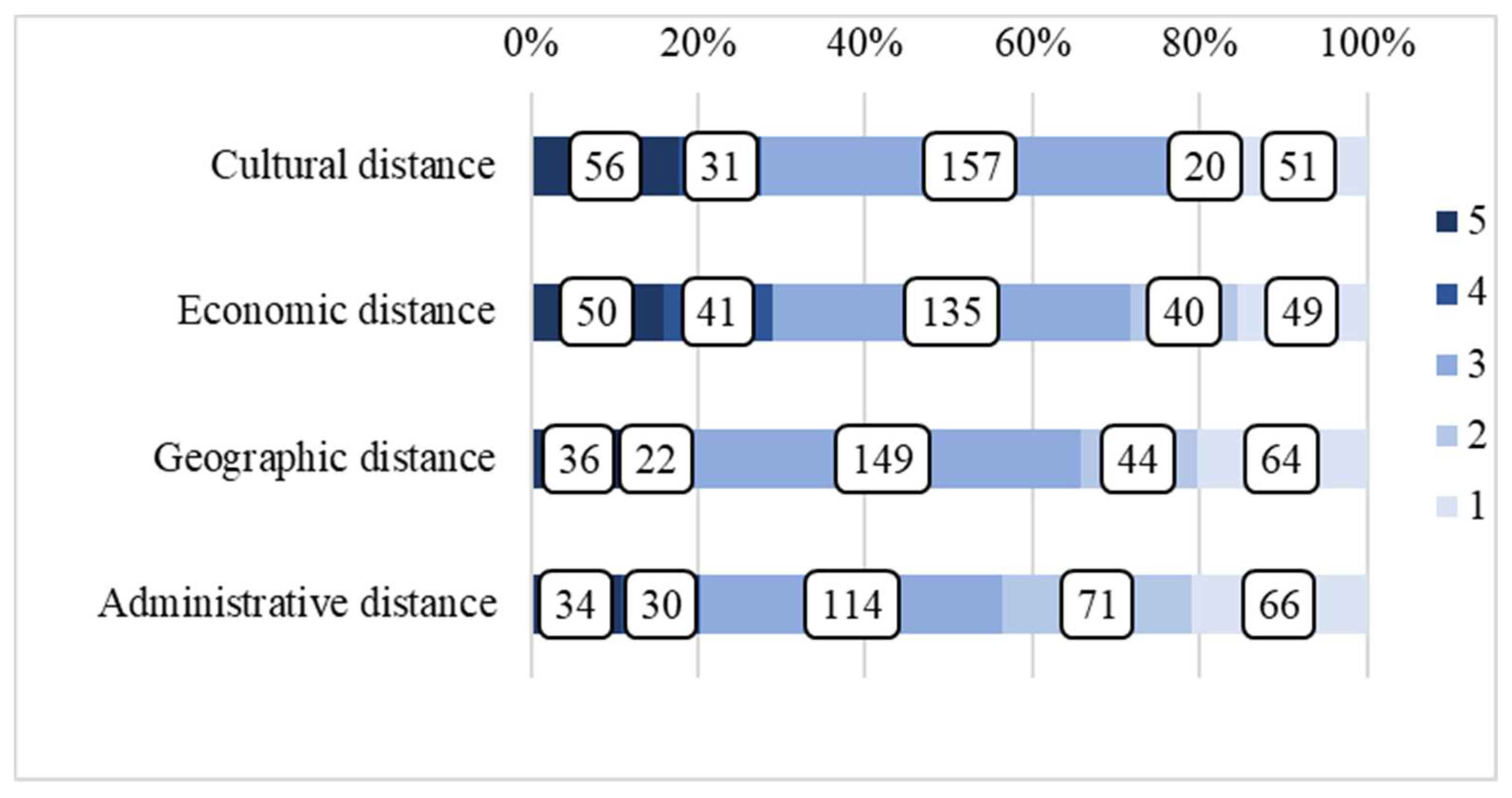

4.4. Perception of Opportunities and Threats Related to Internationalisation

4.5. The Relationship between Sustainability, Digitalisation, Entrepreneurial Perception and Internationalisation

5. Discussion

5.1. Sustainability

5.2. Digital Systems

5.3. Threats and Opportunities—The Entrepreneurial Perception

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Mean | Median | Mode | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural distance | 3.07 | 3.00 | 3 | 1.233 | −0.076 | −0.556 |

| Administrative distance | 2.67 | 3.00 | 3 | 1.218 | 0.320 | −0.630 |

| Geographic distance | 2.75 | 3.00 | 3 | 1.193 | 0.171 | −0.478 |

| Economic distance | 3.01 | 3.00 | 3 | 1.232 | −0.008 | −0.687 |

References

- Hollenstein, H. Determinants of International Activities: Are SMEs different? Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollensen, S. Global Marketing: A Market-Responsive Approach; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Albaum, G.; Strandskov, J.; Duerr, E. International Marketing and Export Management, 3rd ed.; Addison Wesley Longman Ltd.: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Johanson, J.; Wiedersheim-Paul, F. The Internationalization of the Firm-Four Swedish Cases. J. Manag. Stud. 1975, 12, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deresky, H. International Management, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Leonidou, L. An Analysis of the Barriers Hindering Small Business Export Development. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2004, 43, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, S.; Lundgren, E. Internationalization of SMEs; Luleå University of Technology: Luleå, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Langseth, H.; O’Dwyer, M. Forces influencing the speed of internationalisation. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2016, 23, 122–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Barragan, J.M.; Lopez-Sanchez, M.J. The Fast Lane of Internationalization of Latin American SMEs: A Location-Based Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coviello, N.; Kano, L.; Liesch, P.W. Adapting the Uppsala model to a modern world: Macro-context and microfoundations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2017, 48, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoldt, J.; Trapp, T.U.; Toussaint, S.; Süße, M.; Schlegel, A.; Putz, M. Planning for Digitalisation in SMEs using Tools of the Digital Factory. Procedia CIRP 2018, 72, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, W.; Schmid, O. The right digital strategy for your business: An empirical analysis of the design and implementation of digital strategies in SMEs and LSEs. Bus. Res. 2020, 13, 985–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, A.; El Sawy, O.A.; Pavlou, P.A.; Venkatraman, N. Digital business strategy: Toward a next generation of insights. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, H.; Nikou, S.; de Reuver, M. Digitalization, business models, and SMEs: How do business model innovation practices improve performance of digitalizing SMEs? Telecommun. Policy 2019, 43, 101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Martín, M.-Á.; Castaño-Martínez, M.-S.; Méndez-Picazo, M.-T. Digital transformation, digital dividends and entrepreneurship: A quantitative analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenamor, J.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. How entrepreneurial SMEs compete through digital platforms: The roles of digital platform capability, network capability and ambidexterity. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Quvedo, J.; Kesidou, E.; Martínez-Ros, E. Driving sectoral sustainability via the diffusion of organizational eco-innovations. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 29, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escher, I.; Brzustewicz, P. Inter-Organizational Collaboration on Projects Supporting Sustainable Development Goals: The Company Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.; Silva, V.; Sá, J.C.; Lima, V.; Santos, G.; Silva, R. B Corp versus ISO 9001 and 14001 certifications: Aligned, or alternative paths, towards sustainable development? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 29, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.; Perkins, K.M.; Serafeim, G. How to Become a Sustainable Company. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2012, 53, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni, M.P.P.; McAloone, T.C.; Pigosso, D.C.A. Business model innovation for circular economy and sustainability: A review of approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, K.; Balani, S.; Srivastava, P. The relationship among corporate social responsibility, sustainability and organizational performance in pharmaceutical sector: A literature review. Int. J. Pharm. Healthc. Mark. 2021, 15, 572–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, U. Digitainability: The Combined Effects of the Megatrends Digitalization and Sustainability. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 9, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehoff, S.; Beier, G. Industrie 4.0 and a sustainable development: A short study on the perception and expectations of experts in Germany. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 12, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, R.Z.; Herceg, I.V.; Hanák, R.; Hortoványi, L.; Romanová, A.; Mocan, M.; Djurič, D. Industry 4.0 Implementation in B2B Companies: Cross-Country Empirical Evidence on Digital Transformation in the CEE Region. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, O.; Papp, I.; Szabó, R.Z. Construction 4.0 Organisational Level Challenges and Solutions. Sustainability 2021, 3, 12321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.N.; Nguyen, A.H.; Le, T.T.H.; Nguyen, V.P.; Le, T.T.H.; Tran, T.T.H.; Nguyen, N.M.; Le, T.K.O.; Nguyen, T.K.O.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; et al. Can a Short Food Supply Chain Create Sustainable Benefits for Small Farmers in Developing Countries? An Exploratory Study of Vietnam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittersø, G.; Torjusen, H.; Laitala, K.; Tocco, B.; Biasini, B.; Csillag, P.; de Labarre, M.D.; Lecoeur, J.-L.; Maj, A.; Majewski, E.; et al. Short Food Supply Chains and Their Contributions to Sustainability: Participants’ Views and Perceptions from 12 European Cases. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruszkai, C.; Pajtók Tari, I.; Patkós, C. Possible Actors in Local Foodscapes? LEADER Action Groups as Short Supply Chain Agents—A European Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlino, V.M.; Sciullo, A.; Pettenati, G.; Sottile, F.; Peano, C.; Massaglia, S. “Local Production”: What Do Consumers Think? Sustainability 2022, 14, 3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C. Should You Buy Local? J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 176, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denicolai, S.; Zucchella, A.; Magnani, G. Internationalization, digitalization, and sustainability: Are SMEs ready? A survey on synergies and substituting effects among growth paths. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 166, 120650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-X.; Zhao, M.-Z. Economic impacts of ISO 14001 certification in China and the moderating role of firm size and age. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 123059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, P.P.; Oviatt, B.M. International entrepreneurship: The intersection of two research paths. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 902–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutunea, M.F.; Rus, R.V. Business Intelligence Solutions for SME’s. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2012, 3, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanthi, K.; Rao, M.B. Motives, Drivers, and Barriers for Internationalization: A Study of SMEs in Andhra Pradesh. In Transnational, Ethnic and Returnee Entrepreneurship: Perspectives on SME Internationalization; Manimala, M.J., Wasdani, K.P., Vijaygopal, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 213–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pett, T.L.; Francis, J.D.; Wolff, J.A. Examining Sme Internationalization Motives as an Extension of Competitive Strategy. J. Bus. Entrep. 2004, 16, 46–65. [Google Scholar]

- Stallkamp, M.; Schotter, A.P. Platforms without borders? The international strategies of digital platform firms. Glob. Strategy J. 2019, 11, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, K.A.; Lorenzo, O.J. Promoting digitally enabled growth in SMEs: A framework proposal. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2020, 33, 238–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaper, M.; Raar, J. Not so easy being green? Aust. CPA 2001, 71, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cantele, S.; Zardini, A. What drives small and medium enterprises towards sustainability? Role of interactions between pressures, barriers, and benefits. Corp. Soc. Respons. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, E.T. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hamel, G. The Core Competence of the Corporation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990, 68, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korl, Y.Y.; Mahoney, J.T.; Siemsen, E.; Tan, D. Penrose’s The Theory of the Growth of the Firm: An Exemplar of Engaged Scholarship. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2016, 25, 1727–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities: Routines versus entrepreneurial action. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities and entrepreneurial management in large organizations: Toward a theory of the (entrepreneurial) firm. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2016, 86, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarutė, A.; Gatautis, R. ICT Impact on SMEs Performance. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 110, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortoványi, L. The dynamic nature of competitive advantage of the firm. Adv. Econ. Bus. 2016, 4, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. International entrepreneurship: The current satus of the field and future research agenda. In Strategic Entrepreneurship: Creating a New Mindset; Hitt, M.A., Ireland, R.D., Camp, S.M., Sexton, D.L., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 255–288. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, L.; Haug, M. Intention as a cognitive antecedent to international entrepreneurship—Understanding the moderating roles of knowledge and experience. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 7, 111–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulany, D.E. Hypotheses and Habits in Verbal ‘Operant Conditioning’. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1961, 63, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, E.D.; Pasternak, H. An Attitudinal Model to Determine the Export Intention of Non-Exporting, Small Manufacturers. Int. Mark. Rev. 1994, 11, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Palihawadana, D.; Spyropoulou, S. An analytical review of the factors stimulating smaller firms to export. Int. Mark. Rev. 2007, 24, 735–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortoványi, L. Corporate Entrepreneurship; Lambert Academic Publishing (LAP): Beau Bassin, Mauritius, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, S.D. The Decision-Maker and Export Entry and Expansion. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1981, 12, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, S.; Oger, C.; Pruzan-Jorgensen, P.M.; Farrag-Thibault, A. Private-Sector Collaboration for Sustainable Development; Report; BSR: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wasdani, K.P.; Vijaygopal, A.; Manimala, M.J.; Verghese, A.K. Impact of Corporate Governance on Organisational Performance of Indian Firms. Indian J. Corp. Gov. 2021, 14, 180–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.; Pache, A.C.; Birkholz, C. Making hybrids work: Aligning business models and organizational design for social enterprises. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2015, 57, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlange, L.E. Stakeholder Perception in Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Managerial and Organizational Cognition. In Proceedings of the Corporate Responsibility Research Conference, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK, 15–27 July 2007; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vuorio, A.M.; Puumalainen, K.; Fellnhofer, K. Drivers of entrepreneurial intentions in sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn, B.; van der Zwan, P.; Thurik, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Perceived Barriers and Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 1133–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, N.; Audsley, E.; Brodt, S.; Garnett, T.; Henricksson, P.; Kendall, A.; Kramer, K.J.; Murphy, D.; Nemecek, T.; Troell, M. Energy Intensity of Agriculture and Food Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2011, 36, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G. Avoding Asda? Exploring Consumer Motivations in Local Organic Food Networks. Local Environ. 2008, 13, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilali, H.E.; Allahyari, M.S. Transition towards sustainability in agriculture and food systems: Role of information and communication technologies. Inf. Process. Agric. 2018, 5, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebök, A.; Varsanyi, K.; Kujani, K.; Xhakollari, V.; Fricz, A.; Castellini, A.; Gioa, D.; Gaggia, F.; Canavari, M. Value Propositions for Improving the Competitiveness of Short Food Supply Chains Built on Technological and Non-Technological Innovations. Int. J. Food Stud. 2022, 11, SI161–SI181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, M.; Perry, M. Walking the talk? Environmental responsibility from the perspective of small-business owners. Corp. Soc. Respons. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revell, A.; Blackburn, R. The business case for sustainability? An examination of small firms in the UK’s construction and restaurant sectors. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrick, C.N.; Pratt, J.L. Communication and the Narrative Basis of Sustainability: Observations from the Municipal Water Sector. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4428–4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siano, A.; Conte, F.; Amabile, S.; Vollero, A.; Piciocchi, P. Communicating Sustainability: An Operational Model for Evaluating Corporate Websites. Sustainability 2016, 8, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dade, A.; Hassenzahl, D.M. Communicating sustainability: A content analysis of website communications in the United States. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2013, 14, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Trujillo, A.M.; Gonzalez-Perez, M.A. What do we know about organizational sustainability and international business? Manag. Environ. Qual. 2020, 31, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The ISO Survey. Available online: https://isotc.iso.org/livelink/livelink?func=ll&objId=18808772&objAction=browse&viewType=1 (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Fonseca, L. ISO 14001:2015 an improved tool for sustainability. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2015, 8, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L. The EFQM 2020 model. A theoretical and critical review. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2021, 33, 1011–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, L.; Hallberg, P. ISO 14001 adoption and environmental performance in small to medium sized enterprises. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 266, 110592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murmura, F.; Liberatore, L.; Bravi, L.; Casolani, N. Evaluation of Italian Companies’ perception about ISO 14001 and eco management and audit scheme III: Motivations, benefits and barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Noh, Y.; Choi, D.; Rha, J.S. Environmental policy performances for sustainable development: From the perspective of ISO 14001 certification. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; De, P. Environmental sustainability practices and exports: The interplay of strategy and institutions in Latin America. J. World Bus. 2020, 55, 101094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Tapia, I.; Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Manzanares, A. Environmental strategy and exports in medium, small and micro-enterprise. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vencato, C.H.R.; Gomes, C.M.; Scherer, F.L.; Kneipp, J.M.; Bichueti, R.S. Strategic sustainability management and export performance. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2014, 25, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervé, A.; Schmitt, C.; Baldegger, R. Internationalization and Digitalization: Applying digital technologies to the internationalization process of small and medium-sized enterprises. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2020, 10, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemand, T.; Rigtering, C.; Kallmünzer, A.; Kraus, S.; Matijas, S. Entrepreneurial orientation and digitalization in the financial service industry: A contingency approach. In Proceedings of the 25th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Guimarães, Portugal, 5–10 June 2017; pp. 1081–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, A.B.; Boubaker, S.; Dedaj, B.; Carabregu-Vokshic, M. Digitalization of the economy and entrepreneurship intention. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 164, 120043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reim, W.; Yli-Viitala, P.; Arrasvuori, J.; Parida, V. Tackling business model challenges in SME internationalization through digitalization. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, T.; Heikkilä, M.; Nummela, N. Business model innovation for resilient international growth. Small Enterp. Res. 2022, 29, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.; Baldegger, R. Editorial: Digitalization and Internationalization. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2020, 10, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Falahat, M.; Sia, B.K. Drivers of digital adoption: A multiple case analysis among low and high-tech industries in Malaysia. Asia Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2021, 13, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaweł, A.; Mroczek-Dąbrowska, K.; Pietrzykowski, M. Digitalization and Its Impact on the Internationalization Models of SMEs. FGF Studies in Small Business and Entrepreneurship. In Artificiality and Sustainability in Entrepreneurship; Adams, R., Grichnik, D., Pundziene, A., Volkmann, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves, M. Internationalization as an integrated process: Evidence from SMEs in Lusophone Africa. J. Transnatl. Manag. 2022, 27, 37–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolagar, M.; Reim, W.; Parida, V.; Sjödin, D. Digital servitization strategies for SME internationalization: The interplay between digital service maturity and ecosystem involvement. J. Serv. Manag. 2022, 33, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergelova, A.; Manolova, T.; Simeonova-Ganeva, R.; Yordanova, D. SMEs, Democratizing Entrepreneurship? Digital Technologies and the Internationalization of Female-Led. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2018, 57, 14–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassetta, E.; Monarca, U.; Dileo, I.; Di Berardino, C.; Pini, M. The relationship between digital technologies and internationalisation. Evidence from Italian SMEs. Ind. Innov. 2020, 27, 311–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pini, M.; Dileo, I.; Cassetta, E. Digital Reorganization as a Driver of the Export Growth of Italian Manufacturing Small and Medium Sized Enterprises. J. Appl. Econ. Sci. J. 2018, 13, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar]

- Reuber, A.R.; Fischer, E. International entrepreneurship in internet-enabled markets. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-Y.; Falahat, M.; Sia, B.-K. Impact of Digitalization on the Speed of Internationalization. Int. Bus. Res. 2019, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervé, A.; Schmitt, C.; Baldeger, R. Digitalization, Entrepreneurial Orientation and Internationalization of Micro-, Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2020, 4, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, M. Digitalization, Internationalization and Scaling of Online SMEs. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2020, 10, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, M. The Impact of Digitalization on the Speed of Internationalization of Lean Global Startups. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2018, 8, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichocki, A.; Ansari, H.A.; Rusinkiewicz, M.; Woelk, D. Workflow and Process Automation: Concepts and Technology; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, P.M. The ICT revolution, internationalization of technological activity, and the emerging economies: Implications for global marketing. Int. Bus. Rev. 2001, 10, 571–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, V.K.; Elia, M.; van Hillegersberg, J. Software Bots—The Next Frontier for Shared Services and Functional Excellence; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 306, pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghemawat, P. Distance still matters: The hard reality of global expansion. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2001, 79, 137–167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Antunes, I.C.M.; Barandas, H.G.; Martins, F.V. Subsidiary strategy and managers’ perceptions of distance to foreign markets. Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 2019, 29, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebi, T.; Lien, L.; Foss, N.J. What Drives Business Model Adaptation? The Impact of Opportunities, Threats and Strategic Orientation. Long Range Plan. 2017, 50, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staw, B.M.; Sandelands, L.; Dutton, J.E. Threat Rigidity Effects in Organizational Behavior: A Multilevel Analysis. Adm. Sci. Q. 1981, 26, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Jackson, S.E. Categorizing strategic issues: Links to organizational action. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, X.; Wang, Y. Entrepreneurial orientation, social capital, and the internationalization of SMES: Evidence from China. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 54, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, K.G.; Scott, L.R. Person, Process, Choice: The Psychology of New Venture Creation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1992, 16, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuber, A.R.; Fischer, E. The Influence of the Management Team’s International Experience on the Internationalization Behaviors of SMES. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1997, 28, 807–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Dutton, J.E. Discerning threats and opportunities. Adm. Sci. Q. 1988, 33, 370–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falbe, C.M.; Welsh, D.H. NAFTA and franchising: A comparison of franchisor perceptions of characteristics associated with franchisee success and failure in Canada, Mexico, and the United States. J. Bus. Ventur. 1998, 13, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, D.M. Has NAFTA changed North American trade? Econ. Review. Fed. Reserve Bank Dallas 1998, 240, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nachum, L.; Srilata, Z. The persistence of distance? The impact of technology on MNE investment motivations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 747–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Meier, F.; Eggers, F.; Bounckenall, R.B.; Schuessler, F. Standardisation vs. Adaption: A Conjoint Experiment on the Influence of Cultural and Geographical Distance on International Marketing Mix Decisions. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2015, 10, 127–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairncross, F. The Death of Distance: How the Communications Revolution Will Change; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gripsrud, G.; Benito, G.R. Internationalization in retailing: Modeling the pattern of foreign market entry. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1672–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. Book Review. The Gravity Model in International Trade. Advances and Applications. Rev. Int. Econ. 2011, 19, 979–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouncken, R.B.; Cesinger, B.; Kraus, S. The role of entrepreneurial risks in the intercultural context: A study of MBA students in four nations. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2014, 8, 20–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Vahlne, J.-E. The internationalization process of the firm: A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1977, 8, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukamolson, S. Fundamentals of Quantitative Research; Chulalongkorn University: Bangkok, Thailand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/sme-definition_en (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- United Nations: The 17 goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication (accessed on 12 December 2021).

| Classification | Staff Headcount | And | Turnover (EUR) | Or | Balance Sheet Total (EUR) | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large enterprise | 250≤ | and | 50,000,000< | or | 43,000,000< | 20 | 5.9 |

| Medium-sized enterprise | <250 | and | ≤50,000,000 | or | ≤43,000,000 | 64 | 19.1 |

| Small enterprise | <50 | and | ≤10,000,000 | or | ≤10,000,000 | 202 | 60.3 |

| Microenterprise | <10 | and | ≤2,000,000 | or | ≤2,000,000 | 49 | 14.6 |

| Function | Number of People | % |

|---|---|---|

| CEO/founder | 172 | 54.6 |

| Logistics | 14 | 4.4 |

| Finance | 29 | 9.2 |

| Sales and marketing | 37 | 11.7 |

| Product Development | 6 | 1.9 |

| Production | 57 | 18.1 |

| Total | 315 | 100.0 |

| Unstandardized B | S.E. | Hypothesis | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communicating environmental sustainability on corporate website | 0.171 * | 0.067 | H1a | accept |

| The core activity of the company is related to environmental sustainability | −0.051 | 0.065 | H1b | reject |

| ISO 14001 certificate | −0.028 | 0.058 | H1c | reject |

| BI system | 0.021 | 0.062 | H2a | reject |

| ERP system | 0.162 * | 0.063 | H2b | accept |

| CRM system | −0.151 | 0.068 | H2c | reject |

| Workflow system | 0.085 | 0.064 | H2c | reject |

| Document management system | 0.003 | 0.057 | H2d | reject |

| Software robots | 0.050 | 0.061 | H2e | reject |

| Turnover (thousand EUR) | −0.012 | 0.061 | control variable | |

| Staff headcount | 0.048 | 0.062 | control variable | |

| Cultural distance | 0.208 ** | 0.068 | H3a | accept |

| Administrative distance | −0.026 | 0.071 | H3b | reject |

| Geographic distance | 0.056 | 0.072 | H3c | reject |

| Economic distance | 0.132 | 0.076 | H3d | reject |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szabó, R.Z.; Szedmák, B.; Tajti, A.; Bera, P. Environmental Sustainability, Digitalisation, and the Entrepreneurial Perception of Distances as Drivers of SMEs’ Internationalisation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2487. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032487

Szabó RZ, Szedmák B, Tajti A, Bera P. Environmental Sustainability, Digitalisation, and the Entrepreneurial Perception of Distances as Drivers of SMEs’ Internationalisation. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2487. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032487

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzabó, Roland Z., Borbála Szedmák, Anna Tajti, and Péter Bera. 2023. "Environmental Sustainability, Digitalisation, and the Entrepreneurial Perception of Distances as Drivers of SMEs’ Internationalisation" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2487. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032487

APA StyleSzabó, R. Z., Szedmák, B., Tajti, A., & Bera, P. (2023). Environmental Sustainability, Digitalisation, and the Entrepreneurial Perception of Distances as Drivers of SMEs’ Internationalisation. Sustainability, 15(3), 2487. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032487