Measuring Resident Participation in the Renewal of Older Residential Communities in China under Policy Change

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Older Residential Communities’ Regeneration and Citizen Engagement

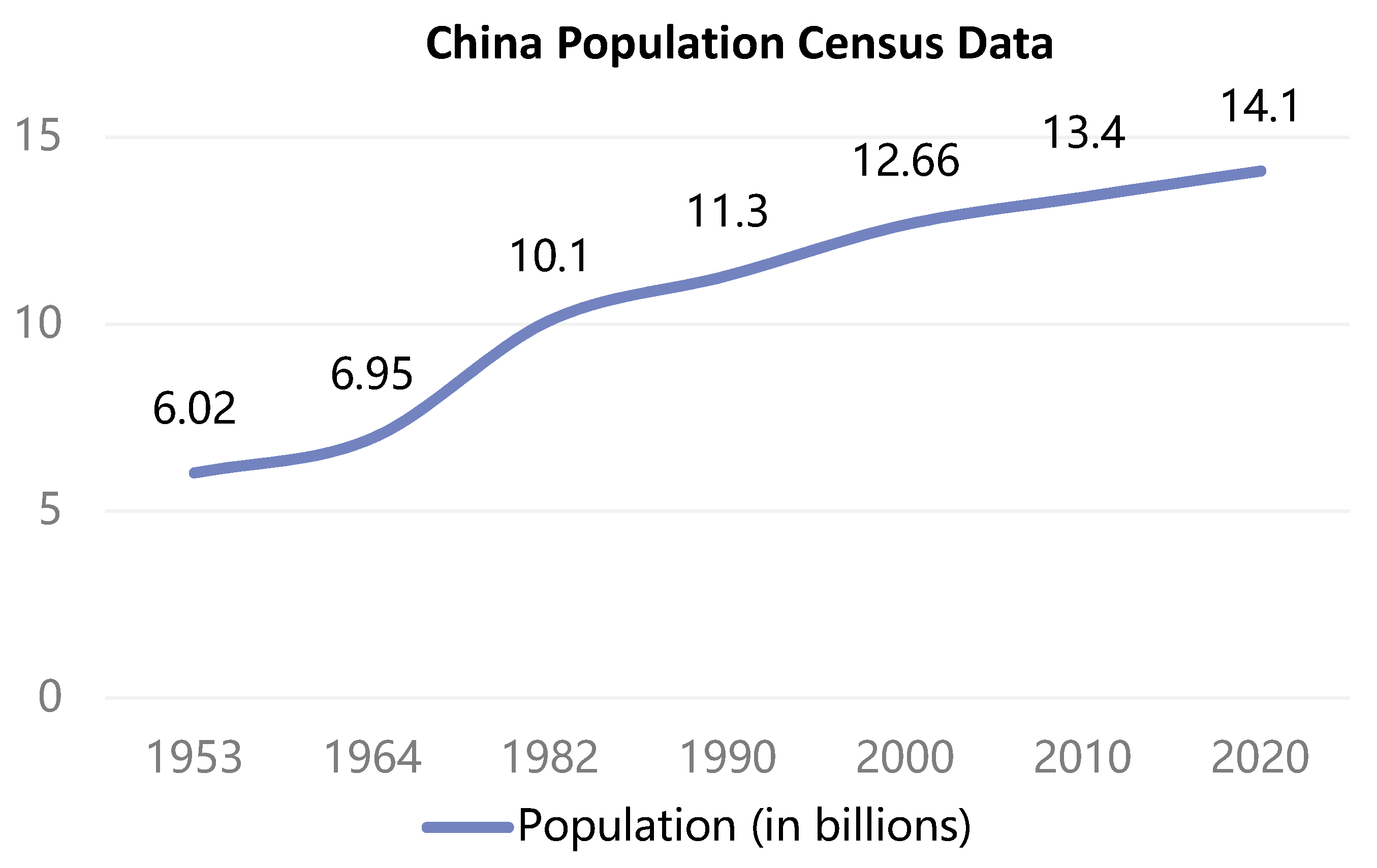

2.2. Development and Policy for the Renewal of Older Residential Areas in China

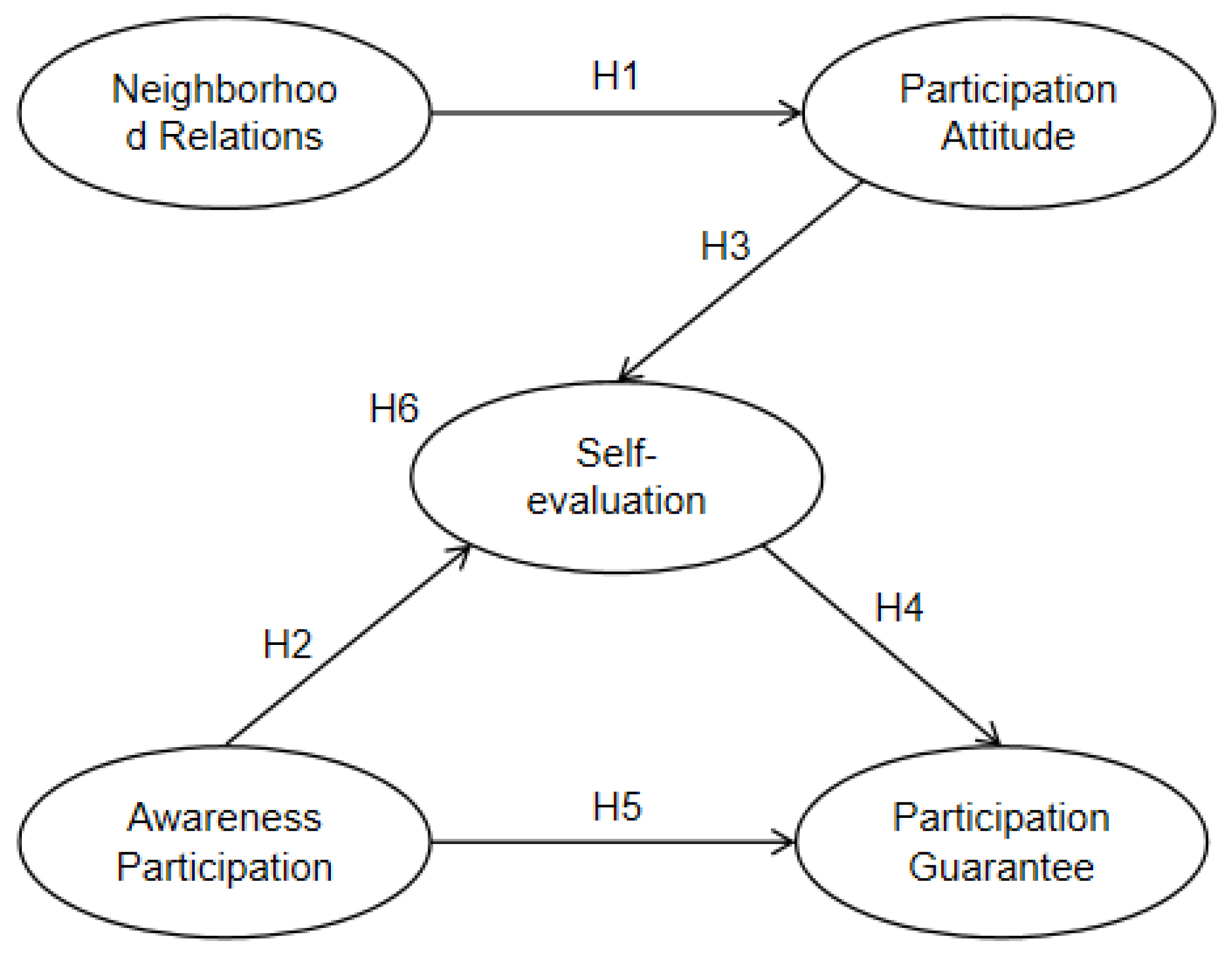

2.3. Previous Studies and Extended Hypotheses

3. Methods

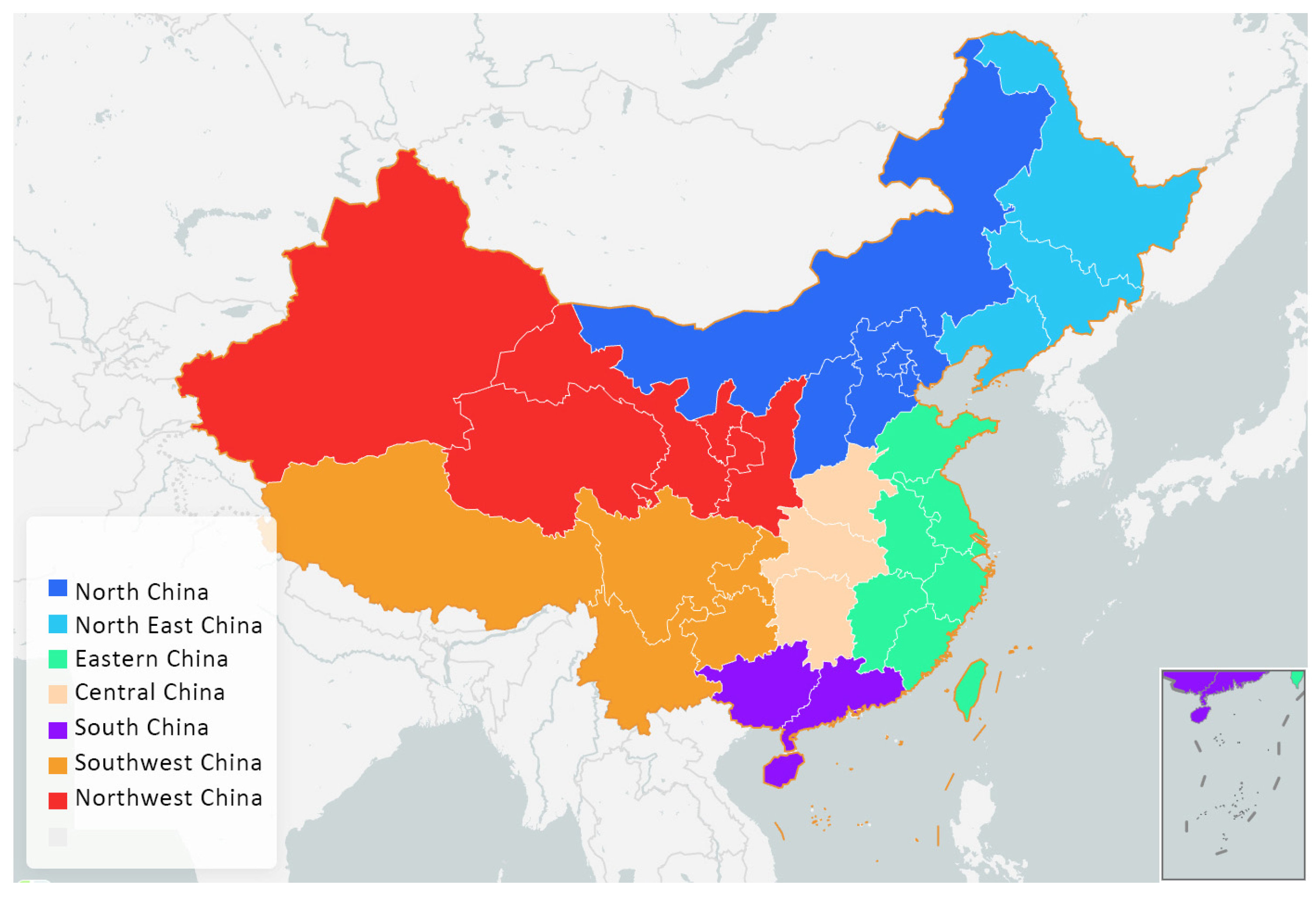

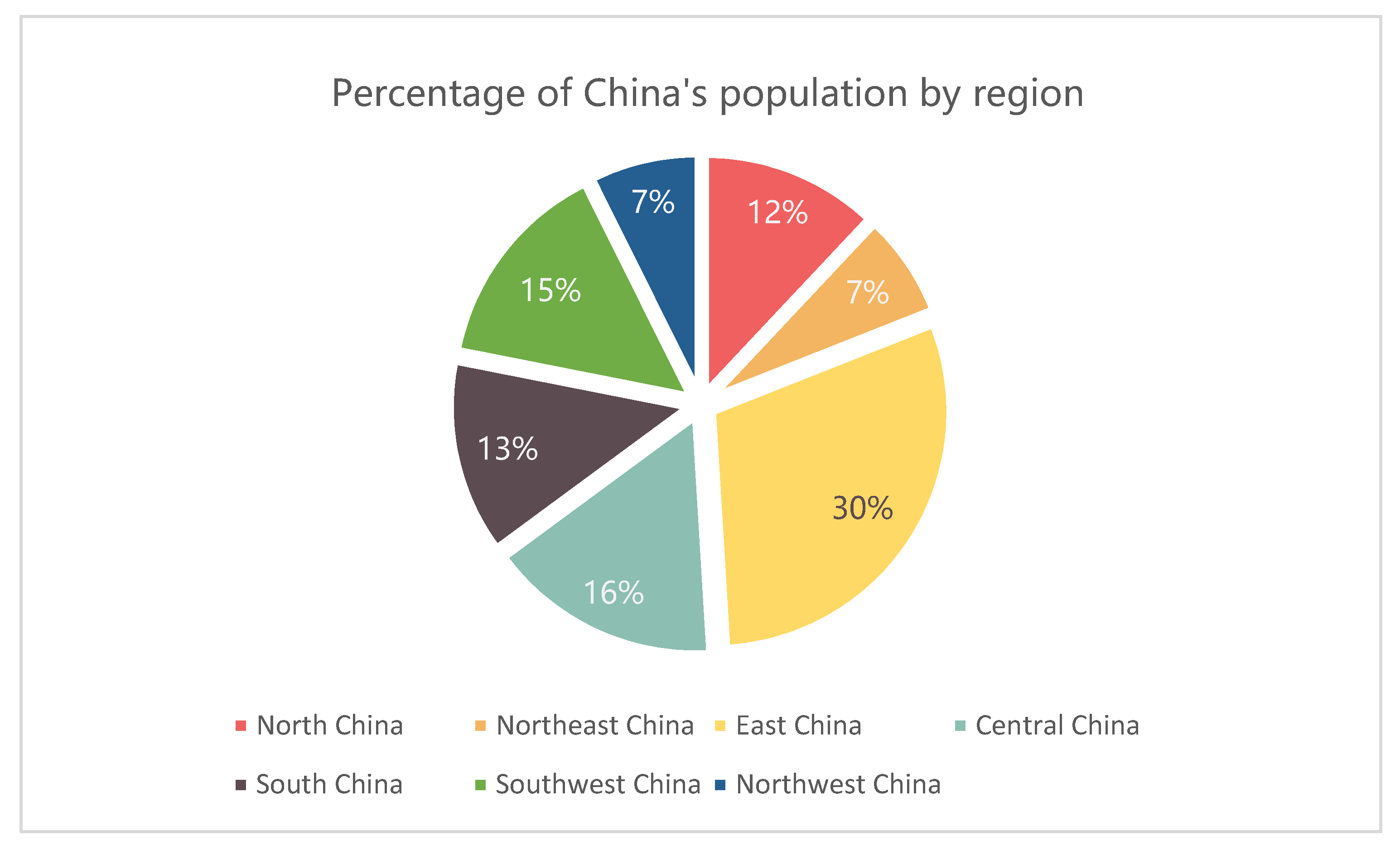

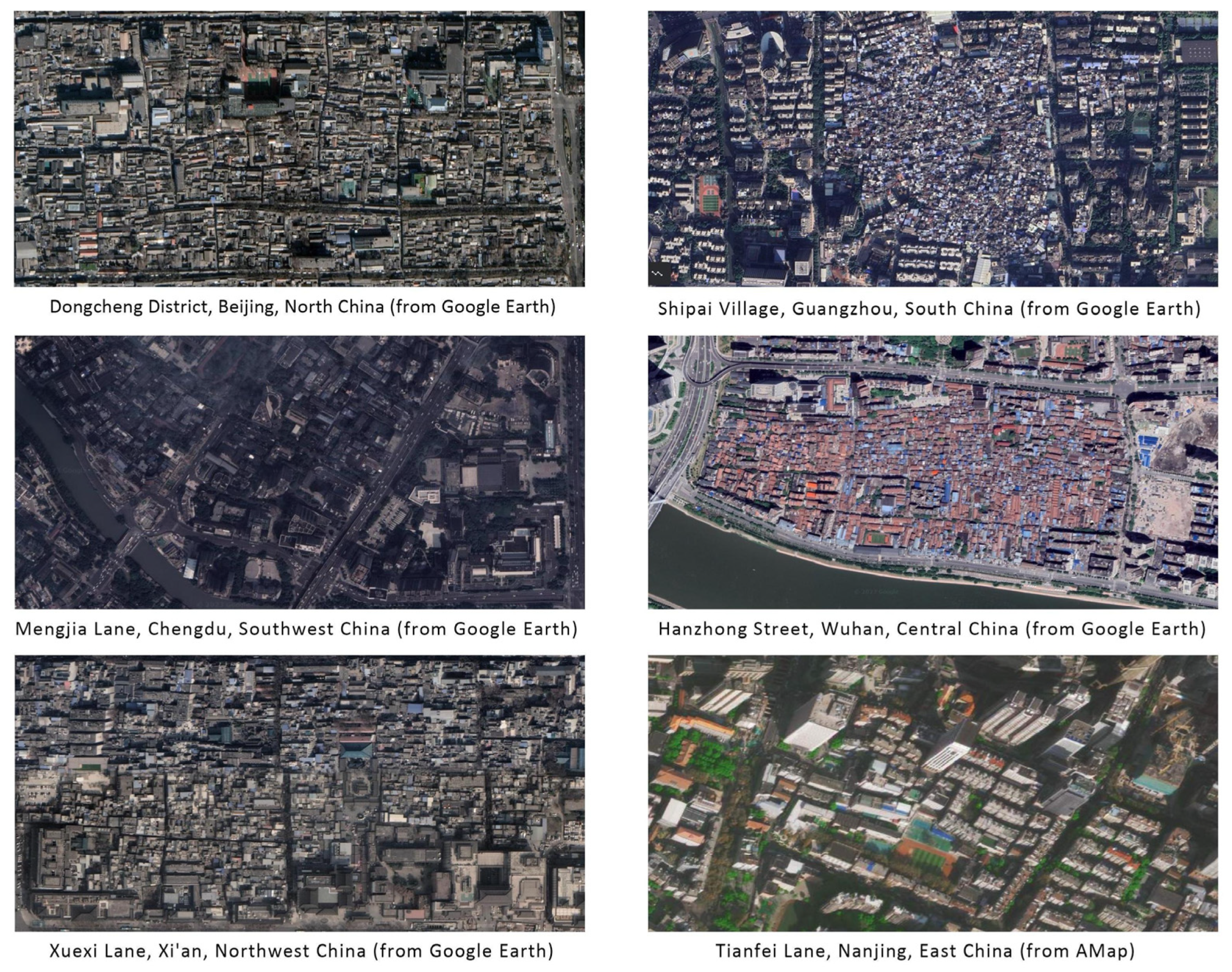

3.1. Geographical Area of Study

3.2. Research Design

3.3. Data Collection

- The questionnaire was explained to the respondents accordingly.

- Personal information of the interviewees.

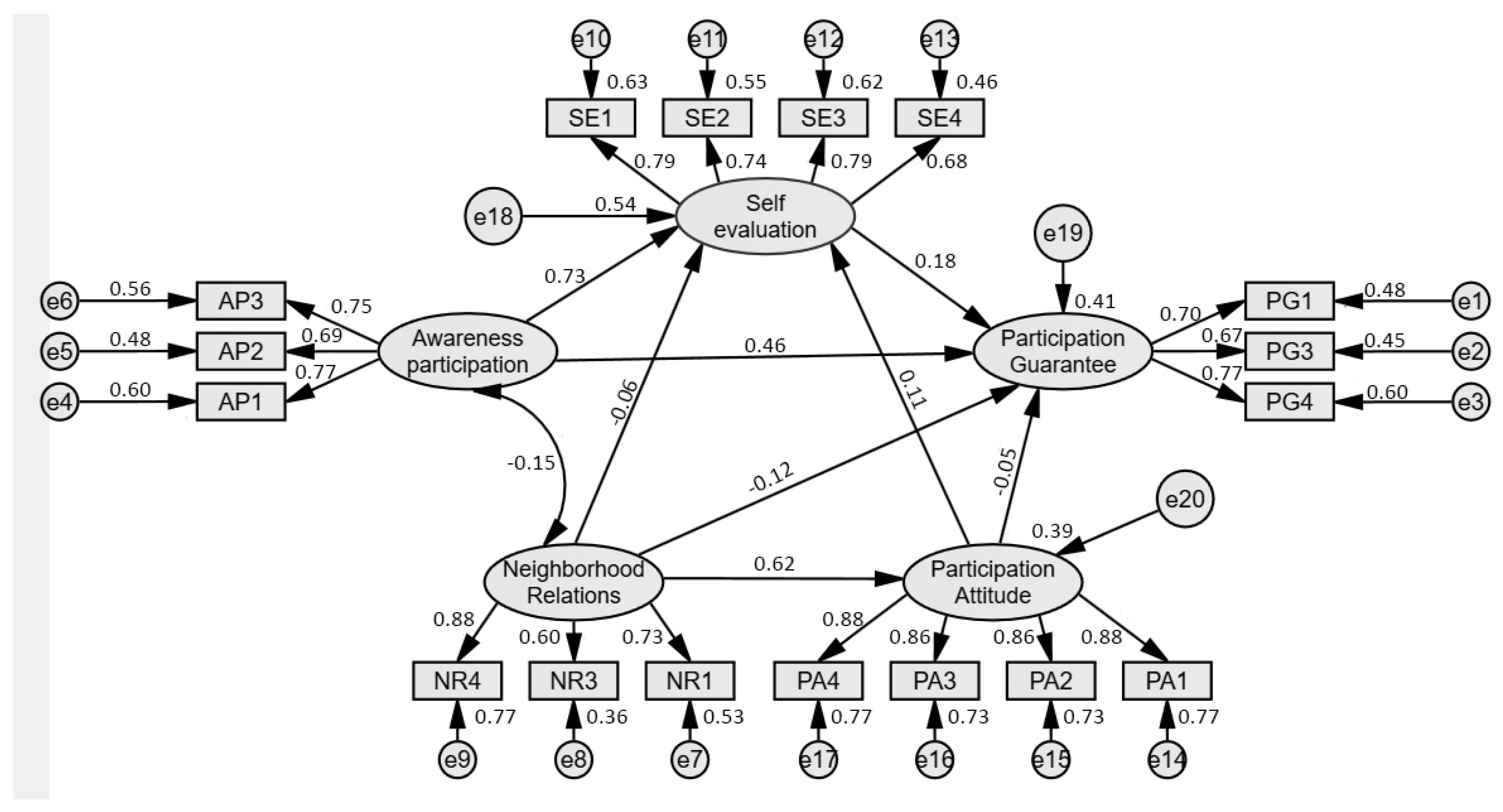

- Factors influencing respondents’ participation behavior, including Participation Guarantee (PG); Awareness Participation (AP); Neighborhood Relations (NR); Self-evaluation (SE); Participation Attitude (PA)

- Respondents’ concerns and perceptions related to the renewal of old residential communities.

| Variables | Indicators | Items |

|---|---|---|

| Participation_Guarantee | PG1 | The extent to which residents’ views are taken into account by the authorities will affect my participation. |

| PG2 | The extent to which the builder values the views of residents will influence my participation. | |

| PG3 | The extent to which third-party social organizations value residents’ views may influence my participation. | |

| PG4 | The ease with which residents can participate affects my participation. | |

| Awareness_participation | AP1 | Willingness to participate in surveys organized by decision-making authorities on the renovation of old residential communities. |

| AP2 | Willingness to participate in surveys organized by third social parties on the renovation of old residential communities. | |

| AP3 | Keep up to date with information on the renovation of older residential areas in my area. | |

| Neighborhood_Relations | NR1 | My familiarity with my neighbors has diminished. |

| NR2 | I have less communication with my neighbors. | |

| NR3 | My neighbors and I have become less helpful to each other. | |

| NR4 | My trust in my neighbors has diminished. | |

| Self-evaluation | SE1 | In my opinion, the old residential community is a poor living environment and needs to be renovated. |

| SE2 | I think I am a socially responsible person. | |

| SE3 | I think I will actively participate in safeguarding the interests of residents. | |

| SE4 | I have my ideas and proposals for the regeneration of older residential communities. | |

| Participation_Attitude | PA1 | Existing engagement channels affect my ability to feed my views and opinions to decision-making authorities. |

| PA2 | Existing engagement channels have affected my ability to provide input and perspective to third-party organizations in society. | |

| PA3 | When my feedback and opinions are not taken seriously, my trust in that department, organization, or institution decreases. | |

| PA4 | I would accept participating in the renewal of an old residential community even if I was not paid accordingly. |

3.4. Analysis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Information

4.2. Reliability and Validity Tests

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

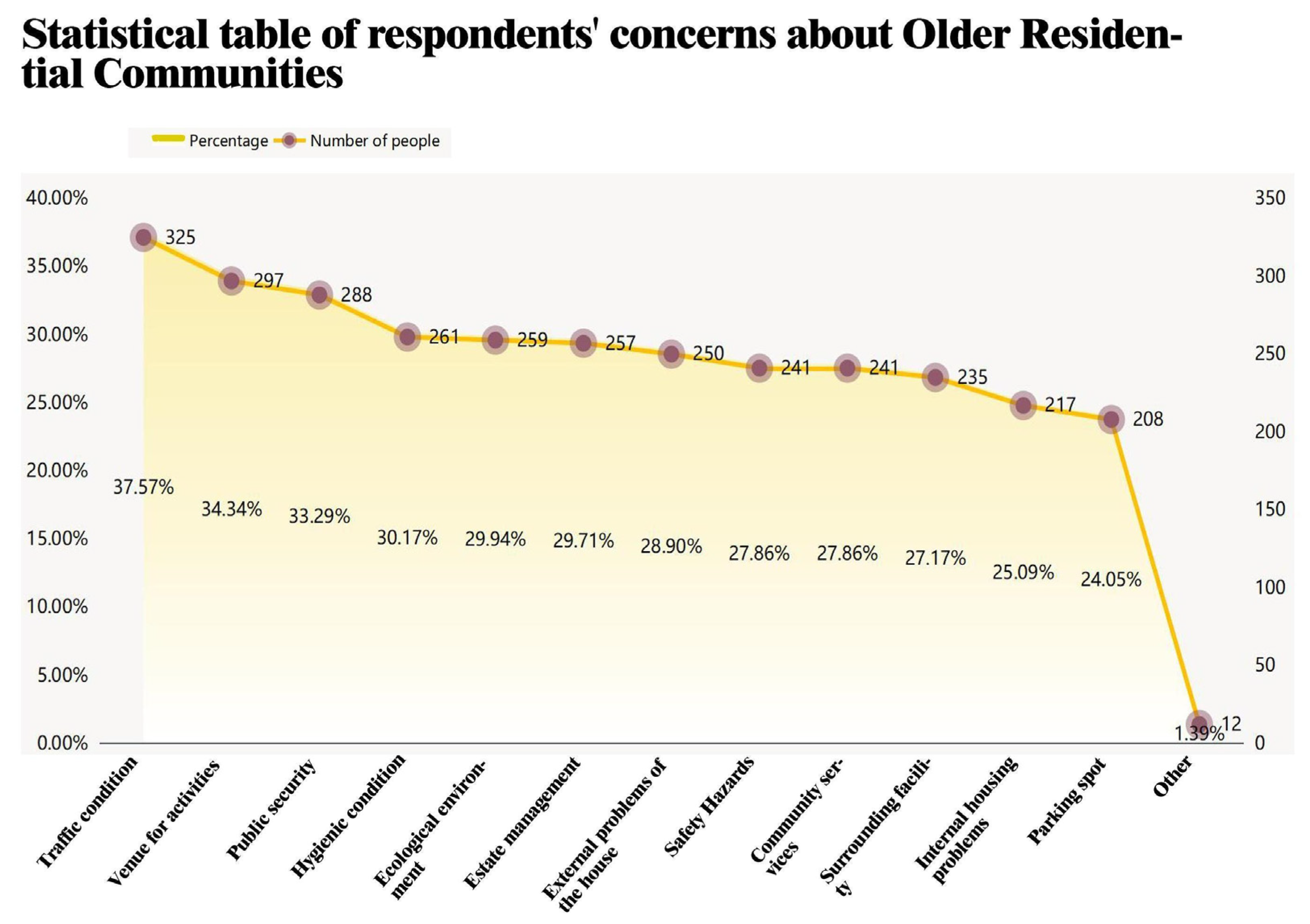

4.4. Respondents’ Concerns and Perceptions about the Renewal of Old Residential Communities

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Basic Information | Answer |

|---|---|

| Gender | Male: 4 Female: 4 |

| Professional Title | Professor: 3 Associate Professor: 5 |

| Education Level | PhD: 5 Master: 2 Other Qualification: 1 |

| Main years of research | 3–5 years: 1 5+ years: 7 |

| Expert Visit Form | |

|---|---|

| Q1 What do you think should be achieved by residents’ participation in the renovation of old residential areas? | |

| Experts | Answer |

| Expert No. 1 | It is necessary to investigate the problems of the old community on the spot and listen to the opinions of the residents. Do not build blindly. Achieve green renewal of old communities. |

| Expert No. 2 | Residential areas become safer, cleaner and more functional |

| Expert No. 3 | Residents’ living conditions are improved, and they can use the transformed environment to carry out certain livelihood activities |

| Expert No. 4 | Listen to what most people think. |

| Expert No. 5 | More consideration of residents’ needs to improve residents’ satisfaction |

| Expert No. 6 | Living comfort, convenience, and safety need to be considered. Let residents make good memories. |

| Expert No. 7 | Realize the participation of residents of all ages and listen to the real needs of residents. |

| Expert No. 8 | In-depth understanding of residents’ demands, improve residents’ participation, and jointly propose solutions according to local conditions with the designer. |

| Q2 What do you think are the problems of residents’ participation in the renovation of old residential areas at this stage? What do you think about this? | |

| Experts | Answer |

| Expert No. 1 | In recent years, the old community renovation model has changed a lot, but the ideas of many officials and residents have not been updated. It is necessary to strengthen the publicity of the policy, let everyone understand the new policy, and unite everyone to rebuild our homes. |

| Expert No. 2 | Some old community updates are cosmetic only and do not address functional issues. The problem should be addressed more systematically. |

| Expert No. 3 | Can the renovation plan proposed by the professional department coordinate residents’ wishes and professional cognition and how to fit the renovated environment with the original living habits? I think this is the direction to think about. |

| Expert No. 4 | There is not enough funding for the renovation of old residential areas, and the small space limits the renovation. I think the government needs to invest more. |

| Expert No. 5 | The renovation of old residential communities is a considerable expenditure, and the source of funds needs to be considered. We should consider whether official investment and private capital can be better utilized to benefit the people. |

| Expert No. 6 | Some residents need to learn more about reconstruction, and they pay too much attention to whether they can get enough economic compensation. Economic benefits, local culture, and memory retention should be considered when implementing renovations. |

| Expert No. 7 | There is no in-depth research on the needs of the masses, and the participation of residents needs to be increased. It is advisable to carry out research work on the groups, take interviews, discussions, and other methods to understand the needs of people of all ages, stimulate the sense of ownership of the masses from face to a point, balance and coordinate various possible contradictions and conflicts, and maximize social value as much as possible. |

| Expert No. 8 | At present, the participation of residents needs to be improved, and many renovation projects are sets of templates that are not targeted. It should be institutionalized and programmed, public opinion should be enhanced, and reform plans should be designed more scientifically. |

References

- David, J. Hess, Coalitions, framing and the politics of energy transitions: Local democracy and community choice in California. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 50, 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Tsendbazar, N.-E.; van Leeuwen, E.; Fensholt, R.; Herold, M. A global analysis of multifaceted urbanization patterns using Earth Observation data from 1975 to 2015. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 219, 104316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Han, Q.; de Vries, B.; Wang, Y. Exploring key determinants of willingness to participate in EIA decision-making on urban infrastructure projects. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S. Analysis of the causes of current social conflicts in China and policy innovation. J. Henan Norm. Univ. 2011, 38, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen, S.; Ojanen, M.; Ott, A.; Saarikoski, H. What about citizens? A literature review of citizen engagement in sustainability transitions research. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 91, 102714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Shin, K.-H.; Park, J.-M.; Kim, C.-G.; Cho, K. Communication problems and alternatives in the process of collecting resident opinions for environmental impact assessment through text mining: A case study of the Dangjin landfill in Korea. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 95, 106781. [Google Scholar]

- Laney, A.R.; Michelle, C.K.; Bernadette, C.H.; Evaine, K.S.; Alison, R.G.; Marc, A.Z. The effects of organizations engaging residents in greening vacant lots: Insights from a United States national survey. Cities 2022, 125, 103669. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmus, E. Contracting with citizens: How residents in Hamburg and New York negotiated development agreements. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwaites, K.; Mathers, A.; Simkins, I. Socially Restorative Urbanism—The Theory, Process and Practice of Experiemics. 1; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J. Analysis and enlightenment of foreign corruption governance path from the perspective of power supervision. Contemp. World Social. 2014, 03, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Xiao, H. Big data application and corruption governance: An in-depth case study based on “Internet plus+supervision”. Jinan J. 2020, 42, 78–94. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Wu, Y. Social exclusion and avoidance: Difficulties and countermeasures in the implementation of support policies for vulnerable groups. J. Jiangxi Norm. Univ. 2021, 54, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. Social Change and Capacity Reconstruction of Marginalized People. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 2008, 06, 3–8+142. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C.; Liu, H. Regional deprivation behavior and regulation path in the process of rapid urbanization. J. Geogr. 2007, 08, 849–860. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, X.; Wu, S. Perception of urban inclusion of relatively vulnerable groups and analysis of influencing factors. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 42, 232–243. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Yang, J.; Gong, Y.; Cheng, Q. An Evaluation of Urban Renewal Based on Inclusive Development Theory: The Case of Wuhan, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaufus, C.; Lindert, P.V.; Noorloos, F.V.; Griet, S. All-Inclusiveness versus Exclusion: Urban Project Development in Latin America and Africa. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, A. The Tide is Rising and the Tide Is Falling: The Gains and Losses of Shanty Reform Policy. Available online: http://www.cmbchina.com/cmbinfo/brand/Brandinfo.aspx?guid=ede8e0c2-81be-44f8-aef5-e38903c75d57 (accessed on 10 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- Lai, X.; Tang, X.; Feng, H. Problems and Countermeasures of Shantytown Reconstruction from the Perspective of Benefit Analysis. Guangxi Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, J. Demolition and Construction Destroy City Memory, History and Culture Disappear. Available online: http://culture.ifeng.com/gundong/detail_2010_08/02/1873025_0.shtml (accessed on 10 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- Yang, B. Practice the concept of” urban double repair and drive urban quality and efficiency improvement. China Landsc. 2021, 37, 44. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals: 17 Goals to Transform our World. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/exhibits/page/sdgs-17-goals-transform-world (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- China National Development and Reform Commission. The 14th Five-Year Plan for the Implementation of New Urbanization. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/fggz/fzzlgh/gjjzxgh/202207/t20220728_1332050_ext.html (accessed on 10 October 2022). (In Chinese)

- Gu, T.; Hao, E.; Ma, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, L. Exploring the Determinants of Residents’ Behavior towards Participating in the Sponge-Style Old Community Renewal of China: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Land 2022, 11, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hoffman, A. A study in contradictions: The origins and legacy of the Housing Act of 1949. Hous. Policy Debate 2000, 11, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. The Federal bulldozer. A critical analysis of urban renewal, 1949–1962. Stanf. Law Rev. 1964, 18, 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, M.; Moore, R. An Analysis of Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1st ed.; Macat Library: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pålsson, K. Public Spaces and Urbanity: Construction and Design Manual: How to Design Humane Cities; DOM Publishers: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stapper, E.; Duyvendak, J. Good residents, bad residents: How participatory processes in urban redevelopment privilege entrepreneurial citizens. Cities 2020, 107, 102898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrubio, C.; Andriotis, K.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, G. Residents’ perceptions of airport construction impacts: A negativity bias approach. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 103983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navratil, J.; Kamil, P.; Stanislav, M.; Nathanail, P.C.; Tureckova, K.; Holesinska, A. Resident’s preferences for urban brownfield revitalization: Insights from two Czech cities. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.S.; Fundo, P.; Kalil, R.M.L.; Rosa, F.D. Community participation in the identification of neighbourhood sustainability indicators in Brazil. Habitat Int. 2021, 113, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.-G.; Shan, M.; Xie, S.; Chi, S. Investigating residents’ perceptions of green retrofit program in mature residential estates: The case of Singapore. Habitat Int. 2017, 63, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Gong, X.; Liu, M. Residents’ behavioral intention to participate in neighborhood micro-renewal based on an extended theory of planned behavior: A case study in Shanghai, China. Habitat Int. 2022, 129, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBSPRC. The Level of Urbanisation Continues to RISE as urban Development Strides Forward-Report No. 17 in the Series on the Achievements of Economic and Social Development in the 70th Anniversary of the Founding of New China. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/shuju/2019-08/15/content_5421382.htm (accessed on 23 October 2022). (In Chinese)

- He, Y. Research on the Periodization of Urban History in New China. Soc. Sci. Res. 2021, 2, 184–193. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Lin, Z. Review and Reflection on China’s Urbanization in the Past 70 Years. Econ. Issues 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F. Comparison of Urbanization between China and Other Developing Countries. Popul. Dev. 2021, 27, 29–38+64. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank WDI Database. World Urbanisation Rate Rankings 2000–2010. Available online: http://www.360doc.com/content/15/0924/02/502486_501146883.shtml (accessed on 23 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- NBSPRC. National Bureau of Statistics Releases Report Showing-China’s Urbanisation Rate Has Risen Sharply in 70 Years. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/shuju/2019-08/16/content_5421576.htm (accessed on 23 October 2022). (In Chinese)

- Ministry of Housing and Construction. Ministry of Housing and Construction: Urbanisation Rate of China’s Resident Population to Reach 64.72% by 2021. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1743931453659163376&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 23 October 2022). (In Chinese)

- ONE.BAR. Urbanisation Rate in 31 Provinces: 8 Provinces Exceed 70%. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1734798645866031298&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 23 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- Zhang, Y.; He, Y. Planning Rationality in the Planned Economy Period: Thoughts, Methods and Space. Planner 2022, 38, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, L. The Change of Urban Housing Supply System in New China from the Perspective of People’s Livelihood. Res. Chin. Econ. Hist. 2017, 5, 144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Analysis of institutional change and contemporary urban household structure change. Popul. Res. 2020, 44, 54–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, W. A review of the research on urban regime construction and social transformation in the early days of the founding of New China. Res. Hist. Communist Party China 2022, 2, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Chen, M.; Lu, D.; Ding, Z.; Zheng, Z. The Spatial Evolution of Geoeconomic Pattern among China and Neighboring Countries since the Reform and Opening-Up. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Si, J. Comprehensively understanding and correctly understanding the socialist market economy. Shanghai Econ. Res. 2022, 1, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, S. The “Old Reform” Project, the Second Spring of Urban Development. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1749622526363768498&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- Paper. Key Words in “Four Histories” How Housing Tensions Have Been Solved in CHINA’S Cities and Towns since the Reform and Opening Up. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1680750218720152051&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- Pan, Z.; Luo, Q.; Wang, S. Comparison, Suggestions and Case Application of Common Development Modes for Shantytown Reconstruction in China. Local Financ. Res. 2016, 04, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Central Government. Ten Measures to Further Expand Domestic Demand and Promote Economic Growth. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/govweb/jrzg/2008-11/10/content_1143831.htm (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese)

- Dazhong Daily. China’s Shanty Construction Starts Slumped This Year; Why the Sharp Brake on a Decade of Shanty Conversions? Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1631841457862300249&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- Gao, H.; Wang, T.; Gu, S. A Study of Resident Satisfaction and Factors That Influence Old Community Renewal Based on Community Governance in Hangzhou: An Empirical Analysis. Land 2022, 11, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBN Daily. Witness the 13th Five-Year Plan the Peak and ebb of Shanty Reform: The Monetization Policy Has Become an Inflection Point. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1684437204729646153&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- Youth.cn. Beijing’s Practical Measures to Promote the Repair and Renewal of Urban Functions. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1609914414992149940&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- Sohu. Urban Repair to Make Up for Urban Shortcomings. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/137984815_488812 (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Guiding Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Comprehensively Promoting the Renovation of Old Urban Areas (Guo Ban Fa [2020] No. 23). Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2020-07/20/content_5528320.htm (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese)

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, J.A.; Chan, I.S.L. Is it just apathy? Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to understand young adults’ (18 to 35 years old) response to government efforts to increase planning participation in Singapore. Urban Gov. 2021, 1, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Ahmad, M.; Ho, Y.-H.; Omar, N.A.; Lin, C.-Y. Applying an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior to Sustainable Food Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteng-Peprah, N.M.; de Vries, M.A. Acheampong, Households’ willingness to adopt greywater treatment technologies in a developing country—Exploring a modified theory of planned behaviour (TPB) model including personal norm. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 254, 109807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaLone, M.B. Neighbors Helping Neighbors: An Examination of the Social Capital Mobilization Process for Community Resilience to Environmental Disasters. J. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2012, 6, 209–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, S.J.; Aubry, T.; Coulombe, D. Neighborhoods and neighbors: Do they contribute to personal well-being? J. Community Psychol. 2004, 32, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, A.; Murie, A.; Groves, R. Social Capital and Neighbourhoods that Work. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1711–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoph, Z. Localized social capital in action: How neighborhood relations buffered the negative impact of COVID-19 on subjective well-being and trust. SSM-Popul. Health 2023, 21, 101307. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Zhang, M.; Guan, N.; Zhang, L.; Gu, T. Research on the Influencing Factors of Residents’ Participation in Old Community Renewal: A Case Study of Nanjing. Constr. Econ. 2019, 40, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z. Factors influencing public participation in urban water environmental governance: Based on the survey data in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. Resour. Sci. 2021, 43, 2289–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, B.P.; Araghi, Y.; Kroesen, M.; Ghorbani, A.; Hakvoort, R.A.; Herder, P.M. Trust, awareness, and independence: Insights from a socio-psychological factor analysis of citizen knowledge and participation in community energy systems. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 38, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.-K.; Kam, P.-K.; Chan, W.-T.; Leung, K.-K. Relationships among the civic awareness, mobilization, and electoral participation of elderly people in Hong Kong. Soc. Sci. J. 2001, 38, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinschenk, A.C.; Christopher, T.D.; Oskarsson, S.; Klemmensen, R.; Nørgaard, A.S. The relationship between political attitudes and political participation: Evidence from monozygotic twins in the United States, Sweden, Germany, and Denmark. Elect. Stud. 2021, 69, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, P.; Ryan, M.; O’Donoghue, C.; Hynes, S.; Huallacháin, D.; Sheridan, H. Impact of farmer self-identity and attitudes on participation in agri-environment schemes. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. The Impact of Public Participation Cognition on Public Participation Behavior-Empirical Analysis Based on Chengdu City. Tianfu New Theory 2013, 04, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, Y.; Wei, M.; Dai, M. How to promote residents’ collaboration in destination governance: A framework of destination internal marketing. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 24, 100710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Study on the Measurement of Residents’ Effective Participation in the Renovation of Old Community-Taking Yingze District of Taiyuan as an Example. Master’s Thesis, Shanxi University of Finance & Economics, Taiyuan, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- China News. The Results of the Seventh National Census Were Released! The Population of China Is 1411.78 Million. Available online: http://www.ncjggw.gov.cn/index.php?a=show&c=index&catid=37&id=7475&m=content (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese)

- Zhang, X.; Dong, F. What affects residents’ behavioral intentions to ban gasoline vehicles? Evidence from an emerging economy. Energy 2023, 263, 125716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecilia, C.; Hsin-yi, W.; Chor-lam, C. Mental health issues and health disparities amid COVID-19 outbreak in China: Comparison of residents inside and outside the epicenter. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 303, 114070. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W. Shenzhen’s House Price Stabilization Ledger: The Number of Residential Land Sales Has Doubled Nine Times in Seven Years, Making More People Able to Afford Housing. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1726654928754299919&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- Hexun Net. Annual Plan for Urban Renewal Projects in Guangzhou in 2022 224 Projects Huangpu and Zengcheng Have the Most. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1737511365519444340&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- China News-Sichuan News. Chengdu will Renovate and Upgrade 313 Old Districts This Year, “Old Look” for a Better New Life. Available online: http://www.sc.chinanews.com.cn/ms/2021-04-16/5049.html (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- Urumqi Evening News. Ten Practical Things to Benefit People’s Livelihood-Urban Renewal Action, 342 Old Districts Renovation Projects All Started. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1738675787530066770&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- JSTV.COM. The 128 Renovation Projects in Nanjing’s Oldest Neighbourhoods Have Started in Full Swing. Available online: http://news.jstv.com/a/20220630/15573604881b4e6db0a3aafdc300f476.shtml (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese).

- Shijiazhuang News. High-Standard Design and High-Quality Construction, 956 Old Residential Communities to be Renovated by the End of October. Available online: https://www.sjz.gov.cn/col/1641437541200/2022/09/24/1663983520034.html (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese)

- Shenyang Internet Information Office. 475 Old Neighborhoods in Shenyang to Be Renovated This Year! The List Is Announced! See If ThereIs Your Home? Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1734542508658343621&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 25 October 2022). (In Chinese)

- Kyoko, O.; Etsuko, K.; Kiyotaka, T. Construction of a structural equation model to identify public acceptance factors for hydrogen refueling stations under the provision of risk and safety information. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 31974–31984. [Google Scholar]

- Manavvi, S.; Rajasekar, E. Assessing thermal comfort in urban squares in humid subtropical climate: A structural equation modelling approach. Build. Environ. 2023, 229, 109931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Chang, D.-F. Exploring International Faculty’s Perspectives on Their Campus Life by PLS-SEM. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walaa, S.E.I.; Mohamed, A.G. Indoor air quality for sustainable building renovation: A decision-support assessment system using structural equation modelling. Build. Environ. 2022, 214, 108933. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Chen, R.; Qin, S.; Liu, L. Evaluating the Public Participation Processes in Community Regeneration Using the EPST Model: A Case Study in Nanjing, China. Land 2022, 11, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; David, F.L. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. SAGE J. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Aguilar, F.; Yang, J.; Qin, Y.; Wen, Y. Predicting citizens’ participatory behavior in urban green space governance: Application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 16, 127110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Qu, H. Influencing factors of counterfeit clothing purchase intention based on cognitive- attitudinal- behavioral intention theory. Adv. Text. Technol. 2022, 30, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wu, J.; Xu, W.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, Z. How Thermal Perceptual Schema Mediates Landscape Quality Evaluation and Activity Willingness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Luo, W.; Kang, N.; Li, H.; Yang, X.; Xia, Y. Study on the Impact of Residential Outdoor Environments on Mood in the Elderly in Guangzhou, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jia, L.; Xiao, J.; Chen, Q.; Gan, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, C.; Wan, C. The Subjective Well-Being of Elderly Migrants in Dongguan: The Role of Residential Environment. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennand, C.A.R.L.; Filho, G.P.R.; Maia, G.; Cunha, F.; Guidoni, D.L.; Villas, L.A. Towards a Fog-Enabled Intelligent Transportation System to Reduce Traffic Jam. Sensors 2019, 19, 3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, D.; Fu, J. Equilibrium between Road Traffic Congestion and Low-Carbon Economy: A Case Study from Beijing, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.; Shahbazi, Z.; Byun, Y. Designing the Controller-Based Urban Traffic Evaluation and Prediction Using Model Predictive Approach. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidubaike. 6–10 Tangshan BBQ Restaurant Beating Incident. Available online: https://baike.baidu.com/item/6%C2%B710%E5%94%90%E5%B1%B1%E7%83%A7%E7%83%A4%E5%BA%97%E6%89%93%E4%BA%BA%E4%BA%8B%E4%BB%B6/61383391?fr=aladdin (accessed on 6 November 2022). (In Chinese).

- Wudaonanlai. You may not have thought of the beating incident in Tangshan Barbecue. Youth J. 2022, 14, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Xinhuanet. The First Trial of the “Tangshan Barbecue Restaurant Beating Case”: The Main Offender Chen Jizhi Was Sentenced to 24 Years in Prison. Available online: http://he.news.cn/xinwen/2022-09/24/c_1129028437.htm (accessed on 6 November 2022). (In Chinese)

- Chen, L.; Cai, P.; Wang, B. Research on the Problems and Improvement Plan of Cost Management in Shanty Town Reconstruction Project. Constr. Econ. 2018, 39, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- CRI.CN. Tianjin Shed Reconstruction: Houses are Placed to Warm People’s Hearts. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1750033334687181470&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 22 November 2022). (In Chinese).

- Dong, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liang, Y. The relationship of tripartite stakeholders in the renovation of old residential areas: A case study of Shenzhen. Geogr. Res. 2021, 40, 779–792. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Items | Number and Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 414 (47.86%) |

| Female | 451 (52.14%) | |

| Age | <20 | 105 (12.14%) |

| 20–34 | 259 (29.94%) | |

| 35–49 | 248 (28.67%) | |

| 50–64 | 186 (21.5%) | |

| >64 | 67 (7.75%) | |

| Education level | Primary school or below | 70 (8.09%) |

| Junior high school | 182 (21.04%) | |

| High school | 231 (26.71%) | |

| Junior college | 202 (23.35%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 180 (20.81%) | |

| Working condition | Unemployment | 60 (6.94%) |

| In employment | 638 (73.76%) | |

| Retired | 52 (6.01%) | |

| Not in working stage | 115 (13.29%) | |

| Monthly income (CNY) | <2000 | 174 (20.12%) |

| 2000–3999 | 137 (15.84%) | |

| 4000–5999 | 215 (24.86%) | |

| 6000–7999 | 207 (23.93%) | |

| ≥8000 | 132 (15.26%) | |

| Location | North China | 101 (11.68%) |

| South China | 119 (13.76%) | |

| East China | 253 (29.25%) | |

| Southwest China | 99 (11.45%) | |

| Northwest China | 67 (7.75%) | |

| Northeast China | 87 (10.06%) | |

| Central China | 139 (16.07%) |

| Component | Initial Eigenvalue | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Variance % | Cumulative % | Total | Variance % | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 4.984 | 29.318 | 29.318 | 4.984 | 29.318 | 29.318 |

| 2 | 3.905 | 22.969 | 52.287 | 3.905 | 22.969 | 52.287 |

| 3 | 1.276 | 7.508 | 59.794 | 1.276 | 7.508 | 59.794 |

| 4 | 1.149 | 6.759 | 66.553 | 1.149 | 6.759 | 66.553 |

| Variables | Indicators | Unstd. | S.E. | C.R. | p | Std. | SMC | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation_Guarantee | PG1 | 1 | 0.696 | 0.484 | 0.758 | 0.512 | 0.754 | |||

| PG3 | 0.886 | 0.055 | 15.985 | *** | 0.673 | 0.453 | ||||

| PG4 | 1.153 | 0.068 | 17.047 | *** | 0.773 | 0.598 | ||||

| Awareness_participation | AP1 | 1 | 0.774 | 0.599 | 0.783 | 0.546 | 0.779 | |||

| AP2 | 0.95 | 0.051 | 18.685 | *** | 0.691 | 0.477 | ||||

| AP3 | 0.956 | 0.048 | 20.048 | *** | 0.750 | 0.563 | ||||

| Neighborhood_Relations | NR1 | 1 | 0.726 | 0.527 | 0.783 | 0.552 | 0.762 | |||

| NR3 | 0.701 | 0.044 | 16.053 | *** | 0.599 | 0.359 | ||||

| NR4 | 1.167 | 0.058 | 19.975 | *** | 0.878 | 0.771 | ||||

| Self-evaluation | SE1 | 1 | 0.794 | 0.630 | 0.839 | 0.566 | 0.838 | |||

| SE2 | 0.945 | 0.043 | 21.831 | *** | 0.743 | 0.552 | ||||

| SE3 | 1.001 | 0.043 | 23.127 | *** | 0.786 | 0.618 | ||||

| SE4 | 0.857 | 0.043 | 19.819 | *** | 0.681 | 0.464 | ||||

| Participation_Attitude | PA1 | 1 | 0.876 | 0.767 | 0.923 | 0.751 | 0.923 | |||

| PA2 | 0.934 | 0.028 | 33.534 | *** | 0.856 | 0.733 | ||||

| PA3 | 0.922 | 0.027 | 33.615 | *** | 0.857 | 0.734 | ||||

| PA4 | 0.985 | 0.028 | 35.024 | *** | 0.877 | 0.769 |

| Fit Indices | Measured Value | Suggested Value | Source | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMID/DF | 3.251 | If 1< χ2/df < 3, the model has a reduced fitting degree; If χ2/df > 5, the model needs to be modified | [24,94] | Supported |

| GFI | 0.952 | If >0.90, the data are ideal | [24,94] | Supported |

| AGFI | 0.933 | If >0.90, the data are ideal | [24,94] | Supported |

| CFI | 0.966 | If >0.90, the data are idea | [24,94] | Supported |

| TLI(NNFI) | 0.958 | If >0.90, the data are idea | [24,94] | Supported |

| RMSEA | 0.051 | If <0.05, the data is ideal; If <0.08, the data are acceptable | [24,94] | Supported |

| NFI | 0.951 | If >0.90, the data are idea | [24,94] | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Path Relationship | Unstd. | S.E. | C.R. | p | Std.(β) | r2 | Hypothesis Testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PA←NR | 0.730 | 0.047 | 15.432 | *** | 0.621 | 0.386 | Supported |

| H2 | SE←AP | 0.758 | 0.047 | 16.288 | *** | 0.733 | 0.542 | Supported |

| H3 | SE←PA | 0.072 | 0.029 | 2.522 | * | 0.107 | Supported | |

| H4 | PG←SE | 0.148 | 0.055 | 2.69 | ** | 0.177 | 0.410 | Supported |

| H5 | PG←AP | 0.400 | 0.062 | 6.487 | *** | 0.461 | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Path | Indirect Effect | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| H6 | AP-SE-PG | 0.113 | 0.003 | 0.239 |

| Concerns and Awareness | 1. Respondents’ concerns about choosing a new home. (Choose 3 items per person) |

| 2. Respondents’ concerns about existing problems in old residential communities. (Choose 3 items per person) | |

| 3. The model of renewal that respondents consider most conducive to solving existing problems in old residential communities. | |

| 4. Considerations for choosing question 3. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, J.; Li, W.; Xu, W.; Yuan, L. Measuring Resident Participation in the Renewal of Older Residential Communities in China under Policy Change. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032751

Wu J, Li W, Xu W, Yuan L. Measuring Resident Participation in the Renewal of Older Residential Communities in China under Policy Change. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032751

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Jiaqi, Wenbo Li, Wenting Xu, and Lin Yuan. 2023. "Measuring Resident Participation in the Renewal of Older Residential Communities in China under Policy Change" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032751

APA StyleWu, J., Li, W., Xu, W., & Yuan, L. (2023). Measuring Resident Participation in the Renewal of Older Residential Communities in China under Policy Change. Sustainability, 15(3), 2751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032751