Designing Our Own Board Games in the Playful Space: Improving High School Student’s Citizenship Competencies and Creativity through Game-Based Learning

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Civic Competencies

- Civic education is one of the core subjects in the 21st century, in which students not only master knowledge about the function of society and government but also foster their competencies to effectively participate in civic life, exercise the rights and obligations of citizenship, and understand how civic decisions impact local and global society [1]. Civic competence is a combination of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values that enable a person to perform real-world tasks such as active civic engagement, including skills of communication, problem-solving, critical and creative reflection, decision-making, responsibility, respect for other values, including awareness of diversity and the attitudes and values of solidarity, human rights, equality, and democracy [21]. Civic competencies are not just about knowledge and skills but also include attitudes and values to adapt to the rapidly changing and multicultural world and face future challenges. The development of various digital tools and media broadens the ways to participate in social events and transforms practices of civic participation. Shah et al. [22] indicated that media use and interpersonal communication are cores of civic competencies, as the media have become a primary way to disseminate public affairs. Nowadays, digital tools allow youths to produce, disseminate, and express civic knowledge through social media [23]. Critical utilisation and consumption of media content and information regarding social events and discussion of public affairs and politics at home and school are showcases for civic competencies. The European Commission [21] indicated that civic competence is a key to lifelong learning. To become a responsible citizen and fully participate in social life, students must possess knowledge of society and culture, an understanding of the role of media in democratic societies, the ability to access and critique various forms of media, attitudes to respect for human rights, responsibility to promote the common good in society and environments, and willingness to participate democratic decision making [21]. Civic competencies can be regarded as a foundation for students to function well and actively participate in society.

- There is no exception in Taiwan, where “social participation”, “communication and interaction”, and “spontaneity” are three core dimensions to becoming a lifelong learner and global citizen in the new Curriculum Guidelines of 12-Year Basic Education [5]. One of the four primary curriculum goals is to inculcate students’ civic responsibility and awareness, which should be achieved by equipping every student with several core competencies, including “planning, execution, innovation, and adaptation”, “cultural and global understanding”, “moral praxis and citizenship”, and “aesthetic, information and media literacies”. All these dimensions echoed the components of civic competencies. Technology has significantly transformed public spheres and youth civic expression and action in various innovative ways in new contexts, including online, offline, and hybrid settings [23]. Although creative thinking is seldom mentioned in prior civic education research, the importance of creativity cannot be neglected, as it helps students solve complicated social problems, participate in society, express their voices through media in creative ways, and show initiative to bring innovation [5].

- Self-rated questionnaires are the primary method to evaluate students’ civic competence and the outcomes of civic education [12,24,25]. However, these questionnaires primarily focus on democracy literacy, the ability, and attitudes to respect different cultures and participate in civic activities, while neglecting other essential dimensions, such as critical consumption of media information and respect for creative expression from different cultures. Additionally, these questionnaires do not provide scenarios to contextualise questions. The civic competencies should be applied in real-life situations based on various contexts instead of asking a series of questions without considering the cultural backgrounds of the respondents. The connection between students’ knowledge, ability, attitude, and real-life merits much attention during evaluation processes and assessments. To thoroughly investigate various dimensions of civic competency and contextualise the current study, we employed the citizen competency test developed by Chen and Hung [26], which provides various scenarios and corresponding questions to investigate students’ attitudes and behaviours in different situations, and has been conducted among Taiwanese secondary school students, and proved an adequate reliability and validity.

1.2. Game-Based Learning as Scaffolding in Learning

1.3. Using Board Games in Civic Education

1.4. From Consumers to Creators: From Playing Board Games to Design Board Games

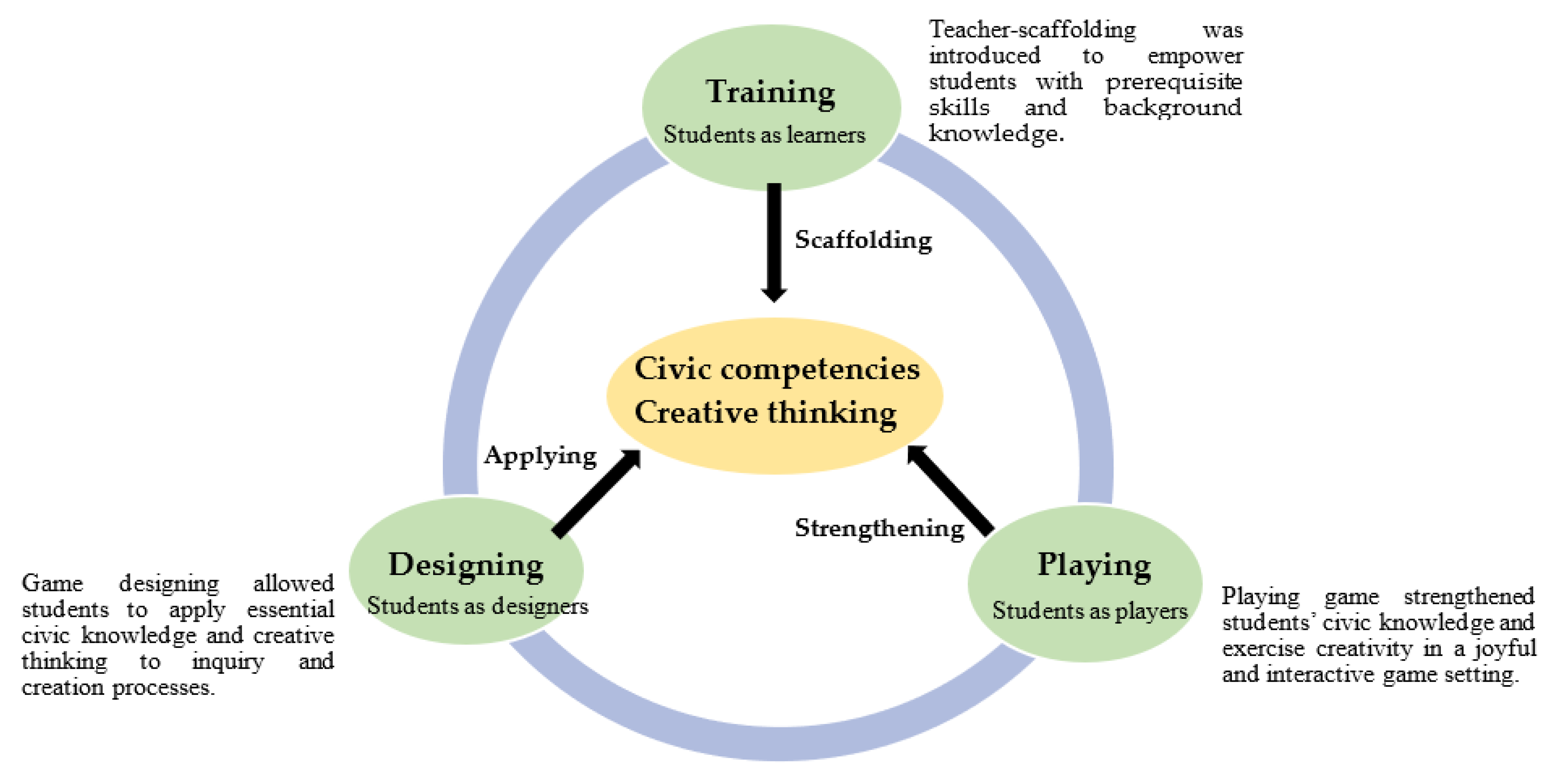

1.5. The Framework Establishment: Tri-Phase Game-Based Learning

- How to develop the Self-designed Board Games (SdBG) course that can enhance high school students’ citizenship competencies and creativity?

- What is the impact of the newly developed SdBG on the students’ creativity?

- What is the impact of the newly developed SdBG on the students’ citizenship competencies?

- What is the difference in the students’ citizenship competencies and creativity between the experimental and control groups?

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Course and Students’ Works

2.2.1. Course Design and Delivery

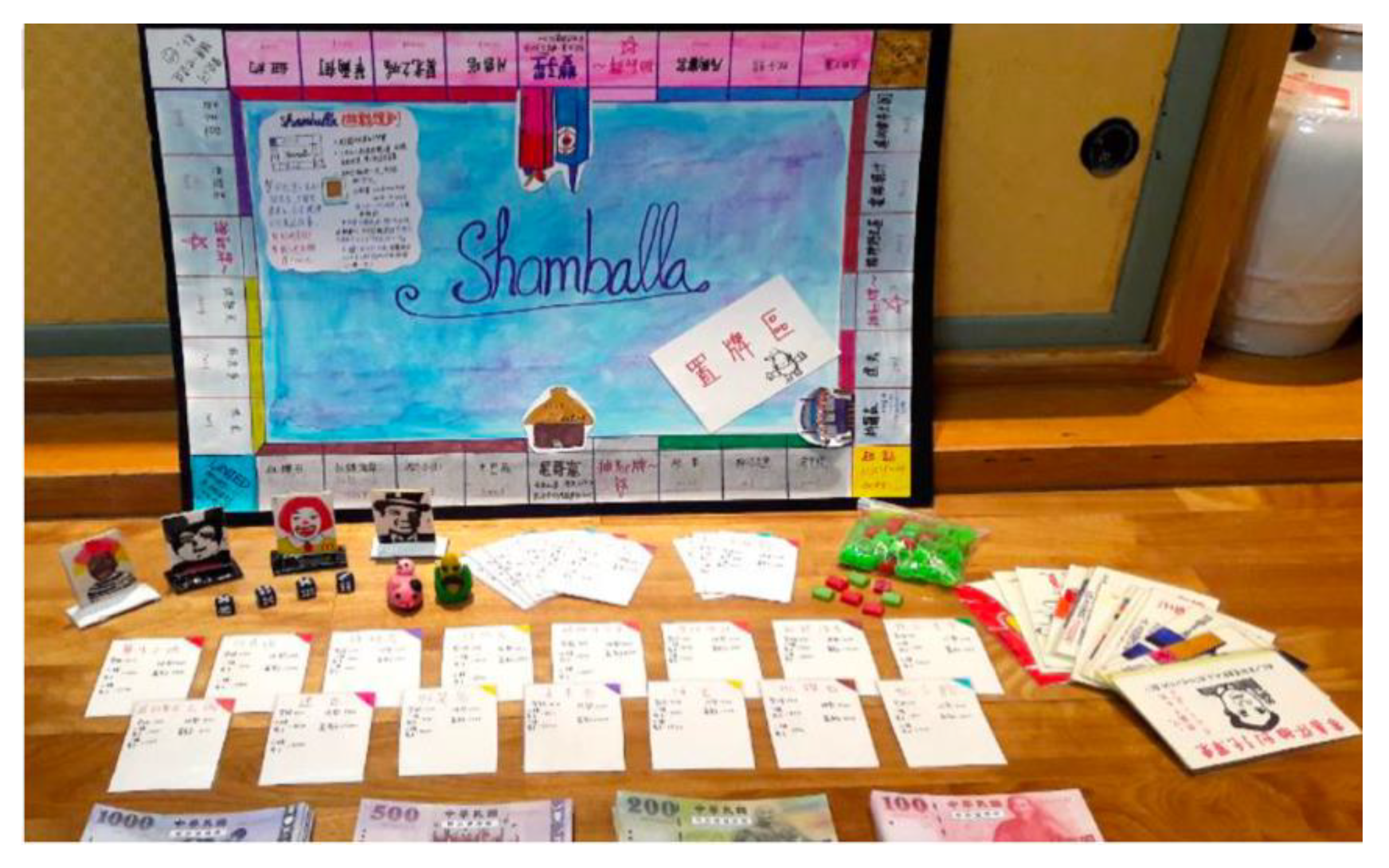

2.2.2. Examples of Students’ Self-Designed Board Games

2.3. Research Instruments

2.3.1. The Modern Citizen Core Competency Test (MCCCT)

2.3.2. The Chinese Version of the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking

3. Result

3.1. Results of the Modern Citizen Core Competency Test

3.1.1. Differences between the Experiment Group and the Control Group in Pretest

3.1.2. Differences between the Experiment Group and the Control Group in the Posttest

3.1.3. The Scores of the MCCCT (Cognitive)

3.1.4. The Test Scores of the MCCCT (Attitude)

3.2. Results for the Chinese TTCT

3.2.1. Verbal Test of the Chinese TTCT

3.2.2. Figural Test of the Chinese TTCT

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Partnership for 21st Century Skills A Framework for Twenty-First Century Learning. 2009. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED519462.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Ministry of Education. Twelve-Year National Basic Education Curriculum Outline Core Competencies Development Manual. National Institute of Education Curriculum and Teaching Research Center Core Competencies Work Circle; Ministry of Education: Taipei, Taiwan, 2015. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.-S. Beliefs and strategies about creative teaching. Taiwan Educ. 2002, 614, 2–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.-T. National Core Competencies: DNA of the Twelve-Year National Curriculum Reform; Higher Education: Taipei, Taiwan, 2014. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Curriculum Guidelines of 12 Year Basic Education: General Guidelines. 2014. Available online: https://www.naer.edu.tw/eng/PageSyllabus?fid=148 (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Amabile, T.M. The motivation to be creative. In Frontiers of Creativity Research: Beyond the Basics; Isaksen, S., Ed.; Bearly Limited: Buffalo, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 223–254. [Google Scholar]

- Cropley, A.J. Creativity in Education and Learning; Stylus: Sterling, VA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Implications of a systems perspective for the study of creativity. In The Handbook of Creativity; Sternberg, R.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 313–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, D.; Atkins, R. Civic competence in urban youth. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2002, 6, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishon, G. Citizenship education through the pragmatist lens of habit. J. Philos. Educ. 2018, 52, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Moreno, C.; Sabariego-Puig, M.; Ambros-Pallarés, A. Developing social and civic competence in secondary education through the implementation and evaluation of teaching units and educational environments. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCompte, K.; Blevins, B.; Riggers-Piehl, T. Developing civic competence through action civics: A longitudinal look at the data. J. Soc. Stud. Res. 2019, 44, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-N.; Liao, Y.-F.; Chang, Y.-L.; Chen, H.-C. A brainstorming flipped classroom approach for improving students’ learning performance, motivation, teacher-student interaction and creativity in a civics education class. Think. Ski. Creat. 2020, 38, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.-C. The Relationship between Schools’ Climate of Creativity, Teachers’ Intrinsic Motivation, and Teachers’ Creative Teaching Performance: A Discussion of Multilevel Moderated Mediation. Contemp. Educ. Res. Q. 2011, 19, 85–125. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Li, L.; Sun, Y. A systematic review of mobile game-based learning in STEM education. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 1791–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plass, J.L.; Homer, B.D.; Kinzer, C.K. Foundations of Game-Based Learning. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 50, 258–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishon, G.; Kafai, Y.B. Connected civic gaming: Rethinking the role of video games in civic education. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2022, 30, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, M. Special series on “effects of board games on health education and promotion” board games as a promising tool for health promotion: A review of recent literature. BioPsychoSocial Med. 2019, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaskulska, M.; Starba, J. Gamification as a tool for civic education—A case study. 21st Century Pedagog. 2020, 4, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, D.; Raichel, N. Equity and Formative Assessment in Higher Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Key Competences for Lifelong Learning; European Union. 2019. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/297a33c8-a1f3-11e9-9d01-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Shah, D.V.; McLeod, J.M.; Lee, N. Communication competence as a foundation for civic competence: Processes of socialization into citizenship. Political Commun. 2009, 26, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirra, N.; Garcia, A. Civic participation reimagined: Youth interrogation and innovation in the multimodal public sphere. Rev. Res. Educ. 2017, 41, 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campillo-Ferrer, J.-M.; Miralles-Martínez, P.; Sánchez-Ibáñez, R. Gamification in higher education: Impact on student motivation and the acquisition of social and civic key competencies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grütter, J.; Buchmann, M. Civic competencies during adolescence: Longitudinal associations with sympathy in childhood. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 50, 674–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Hung, S.-P. Development of a Modern Citizen Core Competencies Test for Middle School Students. J. Educ. Pract. Res. 2019, 32, 39–79. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Noroozi, O.; Dehghanzadeh, H.; Talaee, E. A systematic review on the impacts of game-based learning on argumentation skills. Entertain. Comput. 2020, 35, 100369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Huang, Y.; Xie, H. Digital game-based vocabulary learning: Where are we and where are we going? Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2021, 34, 751–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Hou, H.T. The evaluation of a scaffolding-based augmented reality educational board game with competition-oriented and collaboration-oriented mechanisms: Differences analysis of learning effectiveness, motivation, flow, and anxiety. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, S.V.; Gauthier, A.; Ehrstrom BL, E.; Wortley, D.; Lilienthal, A.; Car, L.T.; Car, J. Serious gaming and gamification education in health professions: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.J.Q.; Lee, C.C.S.; Lin, P.Y.; Cooper, S.; Lau, L.S.T.; Chua, W.L.; Liaw, S.Y. Designing and evaluating the effectiveness of a serious game for safe administration of blood transfusion: A randomized controlled trial. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 55, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piaget, J. Play, Dreams and Imitation in Childhood; W. W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Mental Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Annetta, L.; Mangrum, J.; Holmes, S.; Collazo, K.; Cheng, M.T. Bridging realty to virtual reality: Investigating gender effect and student engagement on learning through video game play in an elementary school classroom. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2009, 31, 1091–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellas, N.; Fotaris, P.; Kazanidis, I.; Wells, D. Augmenting the learning experience in primary and secondary school education: A systematic review of recent trends in augmented reality game-based learning. Virtual Real. 2019, 23, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solhaug, T. Knowledge and self-efficacy as predictors of political participation and civic attitudes: With relevance for educational practice. Policy Futures Educ. 2006, 4, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, C.; Bachen, C.; Lynn, K.-M.; Mckee, K.; Baldwin-Philippi, J. Games for civic learning: A conceptual framework and agenda for research and design. Games Cult. 2010, 5, 199–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, S.; Shirotsuki, K.; Nakao, M. The effectiveness of intervention with board games: A systematic review. BioPsychoSocial Med. 2019, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawamleh, M.; Al-Twait, L.M.; Al-Saht, G. RThe effect of online learning on communication between instructors and students during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Educ. Dev. Stud. 2020, 11, 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borokhovski, E.; Bernard, R.M.; Tamim, R.M.; Schmid, R.F.; Sokolovskaya, A. Technology-supported student interaction in post-secondary education: A meta-analysis of designed versus contextual treatments. Comput. Educ. 2016, 96, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T. Table-top role playing game and creativity. Think. Ski. Creat. 2013, 8, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.T.; Keng, S.H. A dual-scaffolding framework integrating peer-scaffolding and cognitive-scaffolding for an augmented reality-based educational board game: An analysis of learners’ collective flow state and collaborative learning behavioral patterns. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2021, 59, 547–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Pearce, G. A study into the effects of a board game on flow in undergraduate business students. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2015, 13, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegerif, R. Mind Expanding: Teaching for Thinking and Creativity in Primary Education: Teaching for Thinking and Creativity in Primary Education; McGraw-Hill Education: Berkshire, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner, P.A.; Sweller, J.; Clark, R.E. Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 41, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drain, M. Justification of the Dual-Phase Project-Based Pedagogical Approach in a Primary School Technology Unit. Des. Technol. Educ. Int. J. 2010, 15, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Good, K.; Järvinen, E. An Examination of the Starting Point Approach to Design and Technology. J. Technol. Stud. 2007, 33, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.-J.; Chen, F.-Y.; Kuo, J.-S.; Lin, W.-W.; Liu, S.-H.; Chen, Y.-H. The New Version Test of Creative Thinking; Ministry of Education Training Committee: Taipei, Taiwan, 1998. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Phase | Week | Learning Content | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| April 2017 | 1 | Pre-test: Civic competencies and creative thinking tests | |

| Training phase (Students as learners) | 2 | Students learned about concepts and issues relating to the global market and economy. Students watched short videos and discussed in groups about the problems and proposed problem-solving strategies. | Brainstorming and six thinking hats |

| 3 | |||

| 4 | Students learned about how technology and the Internet transformed economic activities and know novel issues stemming from a digital economy. | Mind mapping and brainstorming | |

| 5 | Students learned about how to design board games and the essential principles of enjoyable board games. | Design thinking, mind mapping, brainstorming | |

| 6 | Students learned about how to add aesthetic value to board games and discussed initial subjects and game instructions for their board games. | Brainstorming | |

| Designing phase (Students as designers) | 7 | One of the students’ assignments in extracurricular time is to design board games. Students worked in groups to design characters, cards, and boards for their games. | |

| 8 | |||

| Playing phase (Students as players) | 9 | Students played board games developed by other groups and then discuss in groups to think of how to improve their board games from others’ feedback. | Brainstorming |

| 10 | |||

| 11 | Students selected the most interesting and entertaining board game. Then, the teacher summed up what they learned in these weeks in a debriefing session. | ||

| June 2017 | 12 | Post-test: Civic competencies and creative thinking tests |

| Test | Group | (n) | (M) | (SD) | (df) | (t) | p Value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | Control | 40 | 117.75 | 13.74 | 75 | −1.269 | 0.208 | 0.28 |

| Experiment | 40 | 121.35 | 11.34 | |||||

| Post-test | Control | 40 | 116.02 | 12.49 | 78 | −6.407 | 0.000 *** | 1.43 |

| Experiment | 40 | 131.42 | 8.65 |

| Pretest | Post-Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p | |

| Experiment | ||||||||

| Ethics | 40 | 3.87 | 1.11 | 4.42 | 0.87 | −3.846 | 39 | 0.000 *** |

| Democracy | 40 | 3.75 | 1.40 | 4.70 | 0.99 | −5.208 | 39 | 0.000 *** |

| Scientific | 40 | 3.30 | 1.39 | 4.42 | 1.00 | −5.816 | 39 | 0.000 *** |

| Media | 40 | 2.90 | 1.12 | 4.17 | 0.78 | −6.985 | 39 | 0.000 *** |

| Aesthetic | 40 | 3.62 | 1.65 | 4.75 | 1.00 | −5.719 | 39 | 0.000 *** |

| Total | 40 | 17.37 | 5.18 | 22.47 | 2.94 | −8.803 | 39 | 0.000 *** |

| Control | ||||||||

| Ethics | 40 | 3.47 | 1.19 | 3.42 | 0.87 | 0.422 | 39 | 0.675 |

| Democracy | 40 | 4.25 | 1.29 | 4.12 | 1.34 | 1.706 | 39 | 0.096 |

| Scientific | 40 | 3.20 | 1.22 | 3.22 | 1.16 | −0.374 | 39 | 0.711 |

| Media | 40 | 2.92 | 1.30 | 2.85 | 1.29 | 1.778 | 39 | 0.083 |

| Aesthetic | 40 | 3.22 | 1.68 | 3.07 | 1.52 | 1.356 | 39 | 0.183 |

| Total | 40 | 16.82 | 4.21 | 16.70 | 3.96 | 0.352 | 39 | 0.727 |

| Pretest | Post-Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p | |

| Experiment | ||||||||

| Ethic | 40 | 21.27 | 2.49 | 21.37 | 2.43 | −1.000 | 39 | 0.323 |

| Democracy | 40 | 20.85 | 2.78 | 21.52 | 2.35 | −2.630 | 39 | 0.012 * |

| Scientific | 40 | 22.25 | 2.38 | 22.90 | 1.85 | −2.816 | 39 | 0.008 ** |

| Media | 40 | 21.12 | 2.78 | 22.02 | 2.05 | −3.030 | 39 | 0.004 ** |

| Aesthetic | 40 | 20.67 | 2.93 | 21.12 | 2.75 | −2.516 | 39 | 0.016 * |

| Total | 40 | 106.17 | 10.97 | 108.95 | 8.17 | −4.026 | 39 | 0.000 *** |

| Control | ||||||||

| Ethic | 40 | 20.37 | 2.52 | 19.77 | 1.83 | 2.882 | 39 | 0.006 ** |

| Democracy | 40 | 19.62 | 2.87 | 19.60 | 2.79 | 0.443 | 39 | 0.660 |

| Scientific | 40 | 20.92 | 2.72 | 20.67 | 2.53 | 1.955 | 39 | 0.058 |

| Media | 40 | 19.97 | 2.88 | 19.67 | 3.18 | 1.637 | 39 | 0.110 |

| Aesthetic | 40 | 19.80 | 3.00 | 19.60 | 2.92 | 2.243 | 39 | 0.031 * |

| Total | 40 | 100.70 | 12.08 | 99.32 | 11.02 | 4.078 | 39 | 0.000 *** |

| Pretest | Post-Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p | |

| Experiment | ||||||||

| Fluency | 36 | 48.22 | 7.65 | 64.49 | 8.14 | −11.680 | 35 | 0.000 *** |

| Flexibility | 36 | 49.07 | 9.64 | 62.63 | 8.63 | −8.946 | 35 | 0.000 *** |

| Originality | 36 | 47.04 | 6.79 | 64.49 | 8.69 | −11.341 | 35 | 0.000 *** |

| Total | 36 | 144.33 | 23.45 | 191.61 | 23.32 | −12.179 | 35 | 0.000 *** |

| Control | ||||||||

| Fluency | 40 | 44.56 | 2.76 | 44.00 | 1.86 | 1.771 | 39 | 0.084 |

| Flexibility | 40 | 45.33 | 4.65 | 44.14 | 3.11 | 1.752 | 39 | 0.088 |

| Originality | 40 | 45.04 | 3.63 | 44.58 | 2.75 | 1.346 | 39 | 0.186 |

| Total | 40 | 134.94 | 10.24 | 132.71 | 6.63 | 1.697 | 39 | 0.098 |

| Pretest | Post-Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p | |

| Experiment | ||||||||

| Fluency | 36 | 49.83 | 7.12 | 63.69 | 8.67 | −9.574 | 35 | 0.000 *** |

| Flexibility | 36 | 50.85 | 8.50 | 62.00 | 8.58 | −6.337 | 35 | 0.000 *** |

| Originality | 36 | 49.22 | 6.60 | 63.31 | 10.12 | −11.421 | 35 | 0.000 *** |

| Elaboration | 36 | 46.54 | 3.32 | 65.21 | 9.88 | −11.876 | 35 | 0.000 *** |

| Total | 36 | 196.45 | 22.95 | 254.21 | 30.16 | −13.058 | 35 | 0.000 *** |

| Control | ||||||||

| Fluency | 40 | 45.27 | 3.78 | 42.55 | 2.67 | 4.723 | 39 | 0.000 *** |

| Flexibility | 40 | 45.84 | 5.25 | 42.59 | 4.57 | 4.013 | 39 | 0.000 *** |

| Originality | 40 | 45.43 | 4.18 | 43.30 | 2.66 | 4.178 | 39 | 0.000 *** |

| Elaboration | 40 | 45.27 | 2.43 | 44.16 | 1.17 | 3.161 | 39 | 0.003 ** |

| Total | 40 | 181.81 | 12.72 | 172.60 | 8.71 | 4.924 | 39 | 0.000 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuo, H.-C.; Weng, T.-L.; Chang, C.-C.; Chang, C.-Y. Designing Our Own Board Games in the Playful Space: Improving High School Student’s Citizenship Competencies and Creativity through Game-Based Learning. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042968

Kuo H-C, Weng T-L, Chang C-C, Chang C-Y. Designing Our Own Board Games in the Playful Space: Improving High School Student’s Citizenship Competencies and Creativity through Game-Based Learning. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042968

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuo, Hsu-Chan, Tzu-Lien Weng, Chih-Ching Chang, and Chu-Yang Chang. 2023. "Designing Our Own Board Games in the Playful Space: Improving High School Student’s Citizenship Competencies and Creativity through Game-Based Learning" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042968

APA StyleKuo, H.-C., Weng, T.-L., Chang, C.-C., & Chang, C.-Y. (2023). Designing Our Own Board Games in the Playful Space: Improving High School Student’s Citizenship Competencies and Creativity through Game-Based Learning. Sustainability, 15(4), 2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042968