Do Financial Linkages Ease the Credit Rationing of Forest Rights Mortgage Loans? Evidence from Farm Households in Fujian Province, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

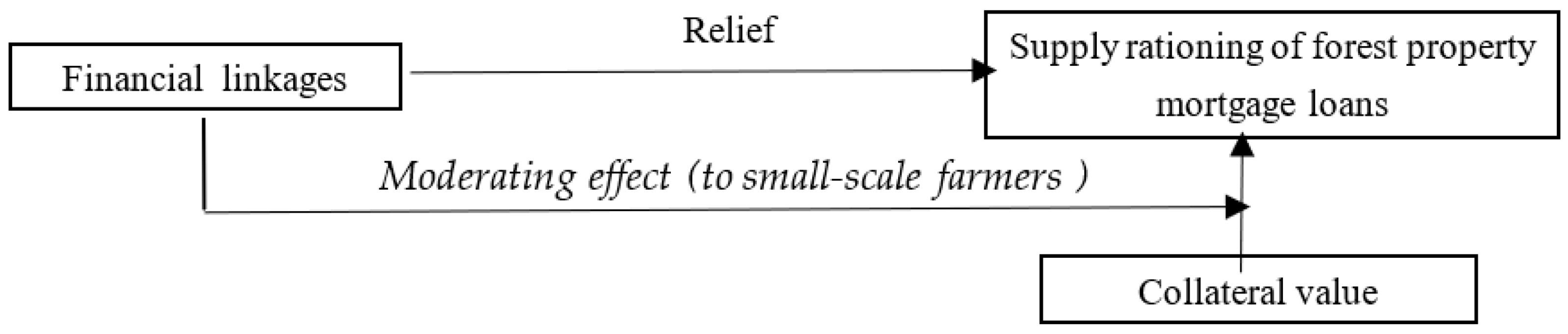

2.1. Financial Linkages and Supply Rationing of Forest Rights Mortgage Loans

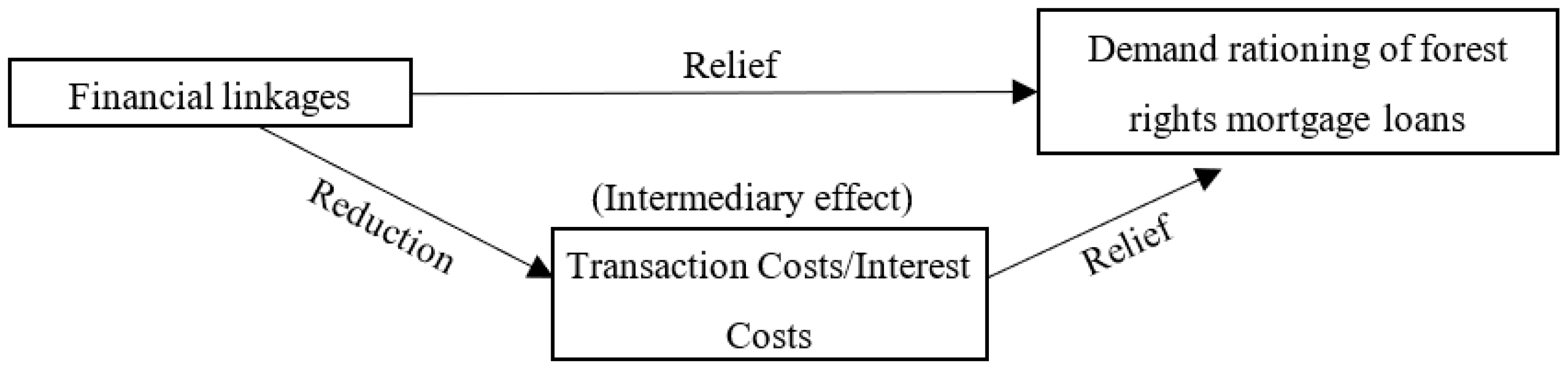

2.2. Financial Linkages and Demand Rationing of Forest Rights Mortgage Loans

3. Research Design

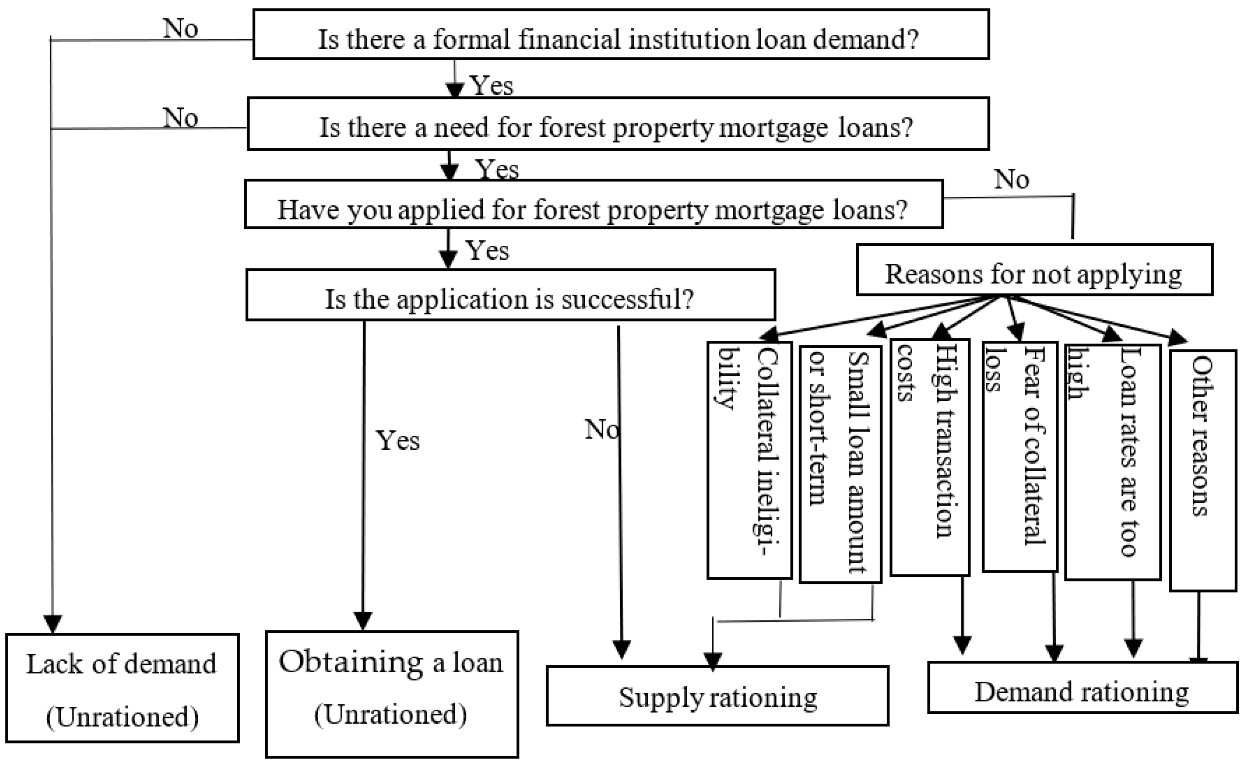

3.1. Identification Methods of Credit Rationing Types for Forest Rights Mortgage Loans

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Methods and Model Construction

3.4. Variable Design

3.4.1. Dependent Variable

3.4.2. Treatment Variable

3.4.3. Control Variables

3.5. Descriptive Statistics of Variables

3.5.1. Statistics of the Credit Rationing Degree

3.5.2. Descriptive Statistics of Control Variables

4. Empirical Results

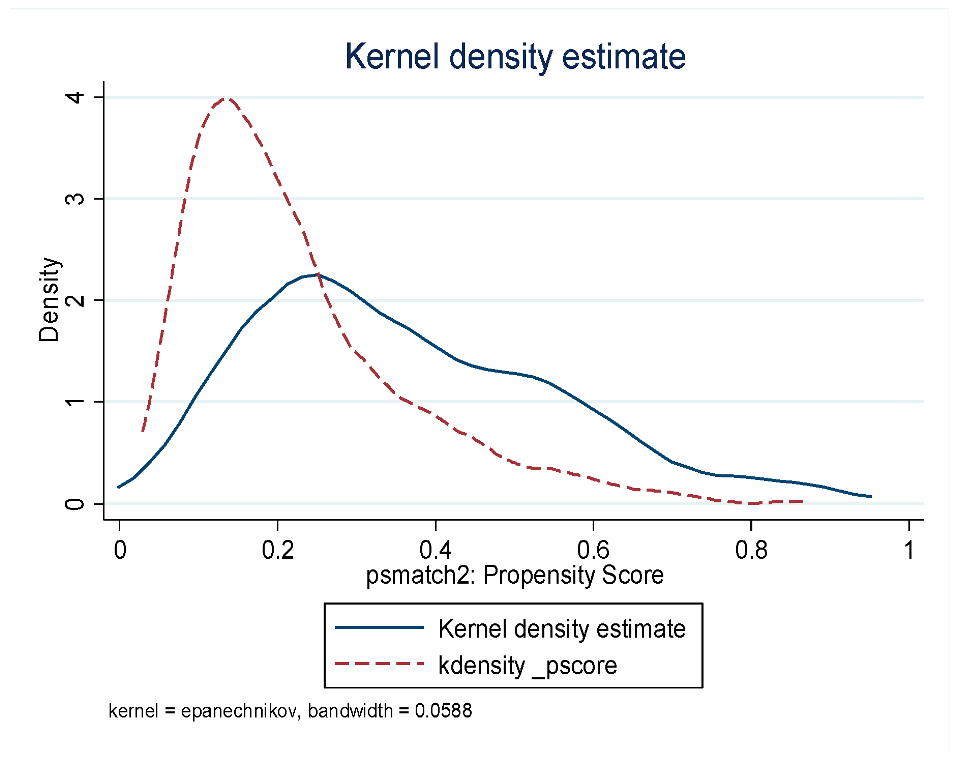

4.1. Estimation of Propensity Scores

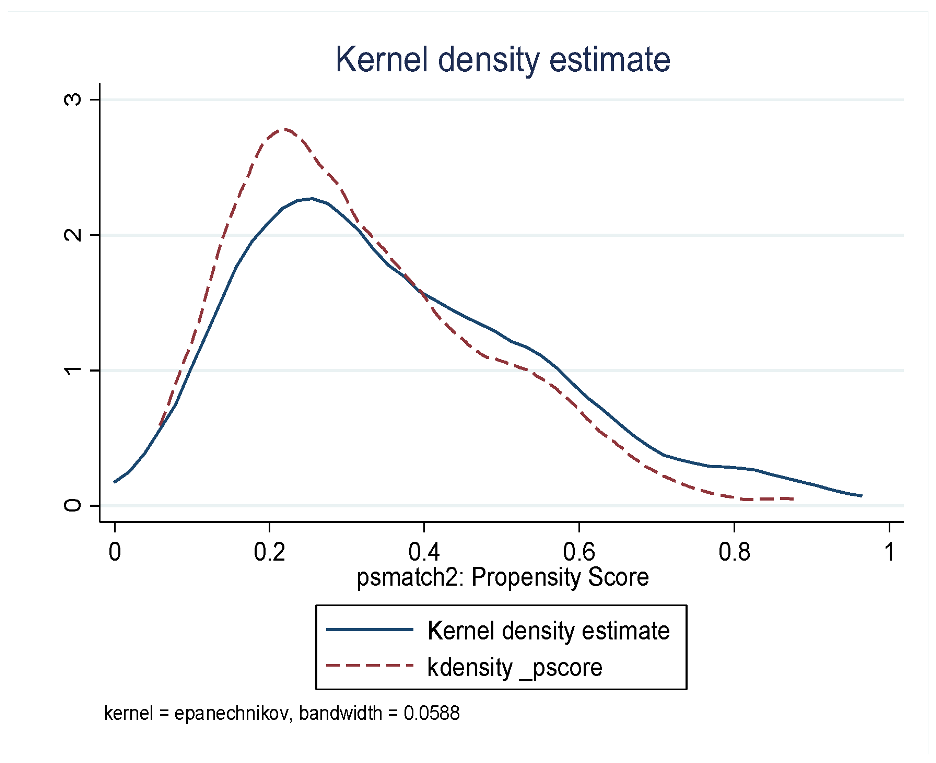

4.2. Balance Test and Common Support Test

4.3. Results of the Effect of Financial Linkages on Credit Rationing

4.4. Heterogeneity Test

5. Mechanism Test

5.1. Moderating Effect Test

5.2. Intermediary Effect Test

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Discussion of Results

6.2. Implications

6.3. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Q.Q.; Dai, Y.W.; Wu, Q.W.; Hong, Y.Z. Forest Rights Mortgage Development History, Realistic Dilemma and Path Exploration. Commu. Financ. Account. 2022, 22, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, M.X. Study on Credit Availability of Forest Right Mortgage Loan by Farmer Households—Based on Thinking of Credit Rationing by Financial Institutions. For. Econ. 2012, 10, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.X. Farmers Forest Right Status Study after the Collective Forest Tenure Reform—Based on the National Policy and Law, Forestry Tenure Reform Policies and Households Survey Data. For. Econ. 2015, 37, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.; Weiss, A. Credit Rationing in Markets with Imperfect Information. Am. Econ. Rev. 1981, 71, 393–410. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, B. Informal High-interest Loans: Passive Behavior or Active Choice?–Based on Survey of 1202 Rural Households in Jiangsu Province. Econ. Sci. 2014, 5, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.K.; Lin, L.F. Analysis on the Credit Rationing of Farmers’ Farmland Mortgage Loans. Issues Agric. Econ. 2021, 7, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.J.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Xu, J.W. How Do Credit Restrictions Affect Farmers’ Credit Availability?–Evidence from Forest Tenure Mortgage Loan System. For. Econ. 2020, 42, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.L. The Forest Rights Mortgage, Credit Rationing and Credit Availability of Farmers—Based on Static Game Model. J. Tech. Econ. Manag. 2017, 4, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Yao, S.P. Effects of Experience Capital and Forestland Scale on Farmers’ Forestry Credit Availability–From Survey of Forest Farmers in Fujian Province—From Survey of Forest Farmers in Fujian Province. J. Northwest AF Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2018, 18, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Q.G.; Hui, X.B.; Yu, L.H.; Wang, C.P. The Analysis Influential Factors and Potential Willingness of Financial Institutions on Land Contract Right Mortgage Loan: Based on a Survey of Rural Loan Officer. Issues Agric. Econ. 2013, 34, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.W.; Wang, J.H.; Zhang, H.X. Study on the Influence of Farmers’ Forest Right Intensity on Their Forest Right Mortgage Availability. For. Econ. 2022, 44, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.H.; Na, S. The Financial Risks and Prevention Strategies of Financial Risk in Forest Right Mortgage Loans-Based on the Perspective of the Credit Risk of Bank. Issues For. Econ. 2015, 35, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.Y.; Pan, L.; Ma, H.C. The Formation Mechanism and Prevention Strategies of Financial Risk in Forest Right Mortgage Loans. For. Econ. 2014, 37, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, S.R.; Guirkinger, C.; Trivelli, C. Direct Elicitation of Credit Constraints: Conceptual and Practical Issues with an Application to Peruvian Agriculture. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2009, 57, 609–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, T.T.; Chen, K. Study on the Influence of Family Resource Endowments on the Forest Right Mortgage Loan Demand under the Background of Collective Forest Property Right Reform-Based on the Survey Data of 460 Heterogeneous Peasants in Liaoning Province. For. Econ. 2020, 42, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Tian, Z.W.; Pan, H.X.; Li, Y.C. Analysis of Chinese forestry households’ credit demand characteristics and constraints -Based on the data from Fujian, Zhejiang, Jiangxi and Guangxi provinces—Based on the data from Fujian, Zhejiang, Jiangxi and Guangxi provinces. Guangdong Agric. Sci. 2012, 39, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, L.Z.; Chen, W. Study on Characteristics and problems of Forest Property Collateral Loan in Yunnan Province. Issues For. Econ. 2014, 34, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhu, S.W.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y. Forest Property Rights Mortgage Loaning: A Research about Bank Financing and Securitization Model. Issues Agric. Econ. 2013, 34, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.Z.; Fu, Y.H. Research on the Accessibility Factors of Forestry Tenure Mortgage Loan for Farm Households-Taking the “Fulin Loan” in Sanming City, Fujian Province as an Example. For. Econ. 2018, 40, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.S.; Dai, W.L.; Dong, L. New Paradigm of Rural Finance: Financial Linkage—Comparative Advantages and Market Microstructure. J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 39, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagura, M.; Kirsten, M. Formal-Informal Financial Linkages: Lessons from Developing Countries. Small Enterp. Dev. 2006, 17, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Wang, J. The Effect of Reputation Transmission Mechanism of Financial Interlinkage on Rural Households’ Credit Rationing. J. Northwest AF Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2022, 22, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, L.Z. The Joint Stock Cooperative System: The Institution Innovation for Forest Right Mortgage Loan. Issues For. Econ. 2016, 36, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Zhao, T.R.; Zhao, R. Research on Forest Tenure Mortgage Loan Mode Innovation in Zhejiang Province. For. Econ. 2018, 40, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.X.; Luo, P.Z.; Yang, W.L. Study on the Current Situation and Problems of Forest Rights Mortgage in Hunan Province, in China. Hunan Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.W.; Li, H.J. Contract Design of Financial Linkage Based on Srackelberg Game. Syst. Eng. 2020, 38, 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, P.B.; Conroy, J.D. Bank-NGO Linkages and the Transaction Costs of Lending to the Poor through Groups. Small Enterp. Dev. 1997, 8, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.; He, G.W. Research on The Linkage Between Rural Credit Cooperative And Community Development Fund. Issues Agric. Econ. 2009, 4, 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.W.; Mi, Y.S.; Zeng, Z.Y. Research on the intervention of developing government in the rural financial linkage: Case study of Mayang County, Hunan Province. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. 2015, 16, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhazhendi, V.; Badatya, K.C. SHG-Bank Linkage Program for Rural Poor: An Impact Assessment. In Proceedings of the Seminar on SHG-Bank Linkage Program, New Delhi, India, 25–26 November 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bester, H. Screening vs. Rationing in Credit Markets with Imperfect Information. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 850–855. [Google Scholar]

- Bester, H. The Role of Collateral in credit market with imperfect information. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1987, 31, 887–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.S.; Zeng, Z.Y.; He, J. The Self-enforcement Mechanism and Formation Mechanism of Interlinked Rural Credits: A Theoretical Analysis from the Perspective of Perspective of Reputation. Econ. Sci. 2016, 3, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.L.; Zhu, M.J.; Zhang, X.Y. The study of the Influence Mechanism of Farmers’ Mutual Financial Cooperative on Farm Households’ Normal Credit Rationing: From the View of “Peer Monitoring” in Cooperative Finance. China Rural. Surv. 2016, 1, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tadelis, S. What’s in Name? Reputation as a Tradeable Asset. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 548–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z. Is the Reform of New Rural Financial Institutions Feasible?–Analysis from the Perspective of Monitoring. J. Econ. Res. 2011, 46, 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.C.; Shi, X.P.; Guan, C.K.; Lan, J. Does the Farmland Operational Right Mortgage Increase the Credit Access of Farmers? Analysis of Moderating Effect Based on Risk Sharing Mechanism. Effect Based on Risk Sharing Mechanism. Chin. Land Sci. 2022, 36, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.S.; Li, J.R.; Mi, Y.S. Participation of Third-Party Organizations, Reduction of Transaction Cost and Availability of Farmland Mortgage: Based on the Perspective of Farmland Disposal. Eco. Rev. 2020, 4, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.J.; Zhao, B. A Study of Farmers’ Borrowing Constraints in China’s Formal Credit Market-An Empirical Analysis Based on a Bivariate Probit Model. Financ. Theor. Prac. 2013, 2, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.K.; Lin, L.F. Can Farmland Management Rights Mortgages Relieve the Credit Rationing of Farmers? Eco. Rev. 2019, 5, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. Coustructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am. Stat. 1985, 39, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.L.; Kong, R. Does Formal Lending Promote Rural Households’ Consumption? An Empirical Analysis based on PSM Method. Chin. Rural Econ. 2019, 8, 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, X.Y.; Wang, J.; Peng, W. Analysis of Interaction between Farmers’ Linkage Behavior and Financial Linkage Efficiency. Financ. Trade Res. 2015, 26, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.L. Factors of Influence on Rural Households’ Credit Choice and Credit Availability: Based on 506 farmers’ survey in Tianjin. Financ. Theor. Prac. 2018, 4, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, R.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.C. Research on The Farmers’ Credit Constraints under Rural Property Mortgage. Issues Agric. Econ. 2016, 37, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.F.; Yu, C.X. Household Farmer’s Potential Demand and its Influencing Factors of Rural Land Management Right Mortgage: Based on the Survey of 191 Non-Experimental Villages in Jiangsu Province. J. Nanjing Agri. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2016, 16, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, D.J.; Xu, Y.P.; Gao, X. Demand and Determinants of Collateral Loan with Forest Property by Farmer Households: A Case Study from Lishui of Zhejiang Province. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2011, 47, 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.L.; Hou, J.T.; Zhang, L. A Comparison of Moderator and Mediator and their Applications. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2005, 2, 268–274. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.P.; Gao, M.Z. Third Party Enhanced Farmland Mortgage Contracts from the Perspective of Social Embeddedness of Transactions: A Case Study of Tongxin Model in Ningxia Province. China Rural. Surv. 2018, 1, 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- He, G.W.; Ding, K.L.; Chen, X.J. Theoretical and practical study on “Trinity” credit cooperation alleviating farmers’ financing constraints: Taking Minyu farmer specialized cooperative as an example. J. Hunan Agri. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2022, 23, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Area | Sample Cities | Sample Counties (Cities and Districts) | Number of Samples | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Fujian | Sanming | Yongan | 135 | 17.20% |

| Youxi | 124 | 15.80% | ||

| Longyan | Zhangping | 125 | 15.92% | |

| Yongding | 58 | 7.39% | ||

| Northern Fujian | Nanping | Jianou | 57 | 7.26% |

| Zhenghe | 57 | 7.26% | ||

| Minnan | Putian | Xiangyou | 58 | 7.39% |

| Zhangzhou | Changtai | 57 | 7.26% | |

| Min Dong | Ningde | Pingnan | 58 | 7.39% |

| Fu An | 56 | 7.13% | ||

| Total | 785 | 100% | ||

| Variable Category | Variables | Code | Variable Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Total rationing | Y1 | Subject to supply rationing or demand rationing; 1 = yes; 0 = no |

| Supply rationing | Y2 | Subject to complete quantity rationing; 1 = yes; 0 = no | |

| Demand rationing | Y3 | Subject to demand rationing; 1 = yes; 0 = no | |

| Explanatory variable | Financial linkage | FL | Participation in financial linkages; 1 = yes; 0 = no |

| Control variables: ① Family characteristics | Age | AGE | Age of farmers |

| Education | EDU | 1 = Elementary school and below; 2 = junior high school; 3 = secondary or high school; 4 = college or bachelor’s degree or above | |

| Household income | HI | 1 = Logarithm of total household income in the previous year | |

| Main source of income | MSI | Working part-time; 2 = business; 3 = fixed wage income; 4 = agricultural production; 5 = forestry production; 6 = government subsidies | |

| Fixed assets | FA | Logarithm of the estimated amount of fixed assets | |

| ② Forest land and forestry specialization characteristics | Forest-land area | FLA | Total area of family forest land (/hm2) |

| Major tree species | MTS | 1 = Bamboo forest and other short-term tree species; 0 = timber forest and other non-short-term tree species | |

| Forest insurance | FI | Participation in forest insurance; 1 = yes; 0 = no | |

| Forestry planting activities | FPA | Engagement in forestry planting activities; 1 = yes; 0 = no | |

| Forestry training | FT | Receive forestry-related training; 1 = yes; 0 = no | |

| ③ Social capital and lending characteristics | Gift expenses | GE | Logarithm of prior year’s gift expense amount |

| Village cadres | VC | Someone in the family is a village cadre; 1 = yes; 0 = no | |

| Other loan experience | OLE | Existence of other loan experience; 1 = yes; 0 = no | |

| Distance to financial institution | DIS | Distance from home to nearest financial institution (/km) | |

| ④ Regional characteristics | Regional policy | RP | 1 = Typical areas for forest rights mortgage promotion; 0 = atypical areas |

| Farmers Type | Obtaining a Loan | Supply Rationing | Demand Rationing | Lack of Demand | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | Number | 68 | 56 | 104 | 557 | 785 |

| Proportion | 8.66% | 7.13% | 13.25% | 70.96% | 100% | |

| Demand sample | Number | 68 | 56 | 104 | / | 228 |

| Proportion | 29.82% | 24.56% | 45.61% | / | 100% | |

| Small-scale farmers | Number | 31 | 49 | 59 | 475 | 614 |

| Proportion of total sample | 5.05% | 7.98% | 9.61% | 77.36% | 100% | |

| Proportion of demand sample | 22.30% | 35.25% | 42.45% | / | 100% | |

| Large-scale farmers | Number | 37 | 7 | 45 | 82 | 171 |

| Proportion of total sample | 21.64% | 4.09% | 26.32% | 47.95% | 100% | |

| Proportion of demand sample | 41.57% | 7.87% | 50.56% | / | 100% | |

| Variable Category | Variables | Total Sample | Treatment Group (A) | Control Group (B) | Difference (A-B) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Err. | ||

| Dependent variable | TR | 0.204 | 0.393 | 0.149 | 0.314 | 0.224 | 0.414 | −0.075 *** | 0.031 |

| SR | 0.071 | 0.257 | 0.047 | 0.192 | 0.080 | 0.276 | −0.033 ** | 0.021 | |

| DR | 0.133 | 0.324 | 0.096 | 0.259 | 0.146 | 0.344 | −0.050 ** | 0.026 | |

| Explanatory variable | FL | 0.265 | 0.441 | 1.000 | 0 | 0.000 | 0 | 1.000 | 0 |

| Control variables: ① Family characteristics | AGE | 53.520 | 10.966 | 52.413 | 9.643 | 53.919 | 11.387 | −1.505 * | 0.886 |

| EDU | 1.871 | 0.786 | 1.932 | 0.816 | 1.849 | 0.775 | 0.083 | 0.064 | |

| HI | 10.953 | 1.025 | 11.096 | 1.085 | 10.901 | 0.998 | 0.195 ** | 0.083 | |

| MSI | 3.178 | 1.658 | 3.034 | 1.573 | 3.230 | 1.686 | −0.197 | 0.134 | |

| FA | 13.329 | 4.305 | 13.761 | 4.350 | 13.008 | 4.289 | 0.753 | 0.349 | |

| ② Forest land and forestry specialization characteristics | FLA | 4.365 | 7.693 | 6.823 | 11.063 | 3.479 | 5.800 | 3.344 *** | 0.811 |

| MTS | 0.561 | 0.496 | 0.451 | 0.498 | 0.601 | 0.490 | −0.149 *** | 0.039 | |

| FI | 0.237 | 0.425 | 0.382 | 0.487 | 0.185 | 0.388 | 0.197 *** | 0.034 | |

| FPA | 0.724 | 0.447 | 0.702 | 0.458 | 0.733 | 0.443 | −0.031 | 0.036 | |

| FT | 0.323 | 0.467 | 0.389 | 0.488 | 0.299 | 0.458 | 0.091 ** | 0.038 | |

| ③ Social capital and lending characteristics | GE | 7.528 | 2.854 | 7.631 | 2.878 | 7.492 | 2.848 | 0.139 | 0.231 |

| VC | 0.415 | 0.493 | 0.442 | 0.497 | 0.405 | 0.491 | 0.037 | 0.040 | |

| OLE | 0.291 | 0.454 | 0.386 | 0.488 | 0.256 | 0.437 | 0.130 *** | 0.036 | |

| DIS | 9.329 | 7.165 | 9.108 | 7.668 | 9.408 | 6.982 | 0.300 | 0.582 | |

| ④ Regional characteristics | RP | 0.417 | 493 | 0.563 | 0.497 | 0.364 | 0.481 | 0.199 *** | 0.039 |

| N | 785 | 208 | 577 | ||||||

| Variable Type | Variable | Regression Coefficient | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family characteristics | AGE | −0.011 | 0.010 |

| EDU | −0.225 * | 0.134 | |

| HI | 0.116 | 0.103 | |

| MSI | −0.103 * | 0.056 | |

| FA | −0.029 | 0.019 | |

| Forest land characteristics and forestry specialization characteristics | FLA | 0.090 *** | 0.031 |

| FLA-Square | −1.188 × 10−3 * | 6.57 × 10−4 | |

| MTS | −0.478 *** | 0.184 | |

| FI | 0.883 *** | 0.220 | |

| FPA | −0.492 ** | 0.209 | |

| FT | 0.358 * | 0.198 | |

| Social capital and lending characteristics | GE | 0.014 | 0.034 |

| VC | 0.032 | 0.192 | |

| OLE | −0.048 *** | 0.015 | |

| DIS | 0.305 * | 0.208 | |

| Regional characteristics | RP | 0.733 *** | 0.211 |

| N | 785 | ||

| LR chi2 | 104.67 *** | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.203 | ||

| Control Variables | Mean Value before Matching | Mean Value after Matching | Deviation Rate after Matching (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Group | Control Group | p-Value | Treatment Group | Control Group | p-Value | ||

| AGE | 52.253 | 53.929 | 0.064 * | 52.408 | 51.429 | 0.341 | 9.3 |

| EDU | 1.950 | 1.853 | 0.137 | 1.921 | 1.948 | 0.749 | −3.3 |

| HI | 11.126 | 10.902 | 0.008 *** | 11.075 | 11.007 | 0.510 | 6.5 |

| MSI | 3.000 | 3.227 | 0.097 * | 2.990 | 2.890 | 0.555 | 6.1 |

| FA | 13.757 | 13.080 | 0.406 | 13.664 | 13.470 | 0.706 | 4.0 |

| FLA | 6.863 | 3.432 | 0.000 *** | 5.804 | 5.044 | 0.394 | 8.5 |

| FLA-Square | 173.844 | 44.372 | 0.000 *** | 124.68 | 85.613 | 0.318 | 9.5 |

| MTT | 0.444 | 0.601 | 0.000 *** | 0.456 | 0.419 | 0.472 | 7.4 |

| FI | 0.384 | 0.186 | 0.000 *** | 0.372 | 0.340 | 0.523 | 7.1 |

| FPA | 0.707 | 0.732 | 0.495 | 0.702 | 0.707 | 0.911 | −1.2 |

| FT | 0.399 | 0.296 | 0.008 ** | 0.387 | 0.419 | 0.533 | −6.6 |

| GE | 7.668 | 7.492 | 0.453 | 7.641 | 7.530 | 0.700 | 3.9 |

| VC | 0.460 | 0.406 | 0.189 | 0.450 | 0.461 | 0.838 | −2.1 |

| LE | 0.394 | 0.255 | 0.000 *** | 0.377 | 0.429 | 0.298 | −11.3 |

| DIS | 8.751 | 9.458 | 0.226 | 8.936 | 9.062 | 0.860 | −1.8 |

| RP | 0.556 | 0.365 | 0.000 *** | 0.539 | 0.550 | 0.838 | −2.1 |

| Matching Method | Treatment Group | Control Group | ATT | Std. Err. | T-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Least-nearest-neighbor matching | 0.105 | 0.257 | −0.152 *** | 0.045 | 3.34 |

| Radius matching | 0.108 | 0.258 | −0.150 *** | 0.033 | 4.50 |

| Nuclear matching | 0.103 | 0.258 | −0.155 *** | 0.033 | 4.67 |

| Average value | 0.105 | 0.258 | −0.152 | - | - |

| Matching Method | Treatment Group | Control Group | ATT | Std. Err. | T-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Least-nearest-neighbor matching | 0.042 | 0.105 | −0.063 ** | 0.031 | −2.01 |

| Radius matching | 0.041 | 0.085 | −0.044 ** | 0.022 | −2.00 |

| Nuclear matching | 0.041 | 0.085 | −0.043 ** | 0.022 | −2.00 |

| Average value | 0.041 | 0.092 | −0.050 | - | - |

| Matching Method | Treatment Group | Control Group | ATT | Std. Err. | T-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Least-nearest-neighbor matching | 0.063 | 0.152 | −0.089 ** | 0.037 | −2.41 |

| Radius matching | 0.067 | 0.173 | −0.106 *** | 0.027 | −3.89 |

| Nuclear matching | 0.062 | 0.173 | −0.111 *** | 0.027 | −4.11 |

| Average value | 0.064 | 0.166 | −0.102 | - | - |

| Type | Farmers’ Classification | Treatment Group | Control Group | ATT | Std. Err. | T-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supply rationing | Smallholder farmers | 0.036 | 0.116 | −0.08 ** | 0.038 | −2.09 |

| Moderate-scale farmers | 0.053 | 0.018 | 0.035 | 0.045 | 0.77 | |

| Demand rationing | Smallholder farmers | 0.043 | 0.109 | −0.065 * | 0.039 | −1.71 |

| Moderate-scale farmers | 0.105 | 0.281 | −0.175 * | 0.095 | −1.84 | |

| Total rationing | Smallholder farmers | 0.080 | 0.225 | −0.146 *** | 0.034 | −4.25 |

| Moderate-scale farmers | 0.169 | 0.355 | −0.185 ** | 0.091 | −2.04 |

| Variables | Sample Type: Small-Scale Farmers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| FLA | −0.022 ** (0.010) | −0.021 ** (0.010) | −0.032 ** (0.014) |

| FL | −0.068 ** (0.034) | −0.246 ** (0.156) | |

| FLA × FL | −0.004 * (0.003) | ||

| Other control variables | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 614 | 614 | 614 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.153 | 0.170 | 0.179 |

| Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial linkages | −0.322 *** (0.077) | 0.178 ** (0.072) | −0.277 *** (0.078) |

| Mediating variable: loan experience | −0.222 *** (0.076) | ||

| Other control variables | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 785 | 785 | 785 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.167 | 0.426 | 0.179 |

| Variables | Treatment Group (A) | Control Group (B) | Differences (A–B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Average | Number | Average | Average | T-Value | |

| Mortgage Annual Interest Rate | 45 | 0.071 | 23 | 0.099 | 0.025 *** | 3.011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Huang, H.; Huang, S.; Chen, S. Do Financial Linkages Ease the Credit Rationing of Forest Rights Mortgage Loans? Evidence from Farm Households in Fujian Province, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043160

Li L, Huang H, Huang S, Chen S. Do Financial Linkages Ease the Credit Rationing of Forest Rights Mortgage Loans? Evidence from Farm Households in Fujian Province, China. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043160

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Li, Heliang Huang, Senwei Huang, and Siying Chen. 2023. "Do Financial Linkages Ease the Credit Rationing of Forest Rights Mortgage Loans? Evidence from Farm Households in Fujian Province, China" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043160

APA StyleLi, L., Huang, H., Huang, S., & Chen, S. (2023). Do Financial Linkages Ease the Credit Rationing of Forest Rights Mortgage Loans? Evidence from Farm Households in Fujian Province, China. Sustainability, 15(4), 3160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043160