Rescuing the Paris Agreement: Improving the Global Experimentalist Governance by Reclassifying Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

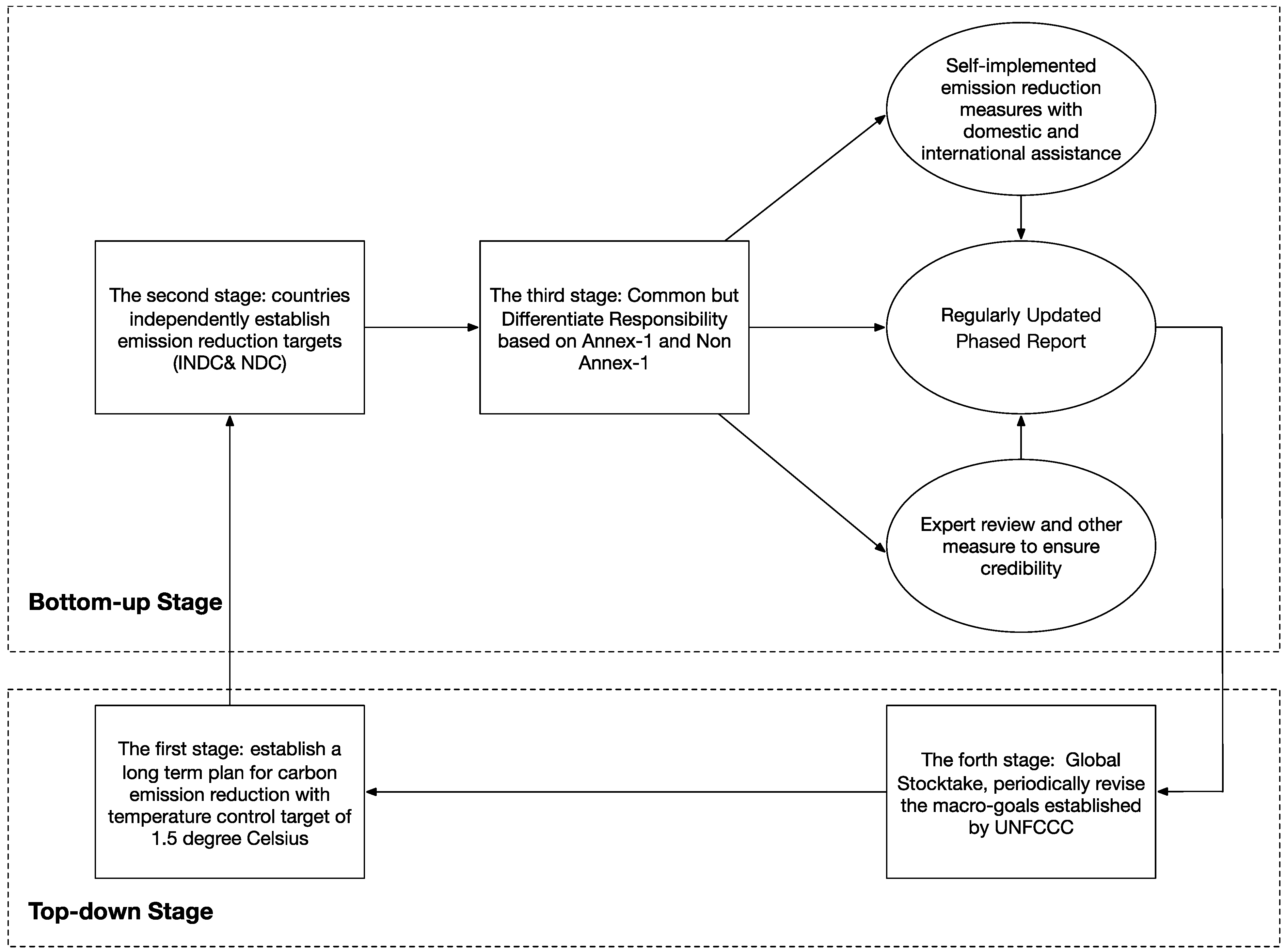

2. The Paris Agreement GEG and Its Predicament

2.1. The GEG in the Paris Agreement

2.2. The GEG Predicament in the Paris Agreement

2.3. The Mismatch of Capability and Motivation in Paris Agreement

2.3.1. Annex I Countries with Strong Capabilities, but Highly Diversified Motivation

2.3.2. Non-Annex I Countries with Uneven National Capacity and Diversified Motivation

2.4. Summary: The Classification of Annex I and Non-Annex I Failed to Mobilize Countries to Join GCCG

3. Reclassifying Countries Based on Their Capability and Motivation

3.1. Criteria for Identifying Countries’ Capabilities and Motivations

3.2. Four Country Types Based on Capability and Motivation

3.3. Climate Action Roadmap for the Different Characters

3.4. Discussion and Valuation of New Classification

4. Conclusions and Final Thoughts

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| High Capability | Low Capability | |

|---|---|---|

| High Motivation | Leader: Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, United Kingdom | Reserve Force: N/A |

| Low Motivation | Waverer: Australia, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Japan, Latvia, Malta, Monaco, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Sweden, Turkey, Ukraine, United States of America, Liechtenstein, Russian Federation | Obscurity: N/A |

| High Capability | Low Capability | |

|---|---|---|

| High Motivation | Leader: Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Brunei Darussalam, Israel, Kuwait, Mauritius, Qatar, Republic of Korea, Saint Kitts and Nevis, United Arab Emirates, Uruguay | Reserve Force: Angola, Argentina, Belize, Benin, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon, Cape Verde (Republic of), Central African Republic, Chad, China, Colombia, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Fiji, Gabon, Gambia, Georgia, Ghana, Guatemala, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Jamaica, Jordan, Kyrgyzstan, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Lebanon, Liberia, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Niger, North Macedonia, Peru, Philippines, Rwanda, Samoa, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Solomon Islands, South Africa, South Sudan, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Syrian, Tajikistan, Togo, Tonga, Tunisia, United Republic of Tanzania, Uzbekistan, Viet Nam, Zimbabwe |

| Low Motivation | Waverer: Albania, Andorra, Bahamas, Bahrain, Chile, Cook Islands, Costa Rica, Niue, Oman, Palau San Marino, Seychelles, Singapore, Trinidad and Tobago | Obscurity: Afghanistan, Algeria, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Bolivia, Botswana, Comoros, Republic of the Congo, Cuba, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Dominica, Egypt, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, India Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kiribati, Lesotho, Libya, Madagascar, Malaysia, Maldives, Marshall Islands, Mexico, Micronesia, Nauru, Nepal, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Palestine, Pakistan, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Republic of Moldova, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Sao Tome and Principe, Serbia, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu, Uganda, Vanuatu, Venezuela, Yemen, Zambia |

References

- Sabel, C.F.; Victor, D.G. Fixing the Climate Strategies for an Uncertain World; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA; Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 151–169. [Google Scholar]

- De Búrca, G.; Keohane, R.O.; Sabel, C. Global experimentalist governance. Br. J. Political Sci. 2014, 44, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, M.; Stewart, R.B.; Rudyk, B. Building blocks for global climate protection. Stanf. Environ. Law J. 2013, 32, 341–392. [Google Scholar]

- Grubb, M. From Lima to Paris, part 1: The Lima hangover. Clim. Policy 2015, 15, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabel, C.F.; Victor, D.G. Governing global problems under uncertainty: Making bottom-up climate policy work. Clim. Chang. 2017, 144, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homsy, G.C.; Liu, Z.; Warner, M.E. Multilevel governance: Framing the integration of top-down and bottom-up policymaking. Int. J. Public Adm. 2019, 42, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Búrca, G.; Keohane, R.O.; Sabel, C. New Modes of Pluralist Global Governance. N. Y. Univ. J. Int. Law Politics 2013, 45, 723. [Google Scholar]

- Ban Ki-moon, Ban Spotlights Need for International Cooperation to Preserve Ozone Layer, Protect Environment. Available online: https://news.un.org/story/2013/09/449082 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Keohane, R.O.; Oppenheimer, M. Paris: Beyond the climate dead end through pledge and review. Politics Gov. 2016, 4, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhl, J.B.; Salzman, J. Introduction: Governing Wicked Problems. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2020, 73, 1561. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, B. Market failure, government failure and externalities in climate change mitigation: The case for a carbon tax. Public Adm. Dev. Int. J. Manag. Res. Pract. 2008, 28, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wucker, M. The Gray Rhino: How to Recognize and Act on the Obvious Dangers We Ignore; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, K.W. The transnational regime complex for climate change. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2012, 30, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ol-livier-Mrejen, R.; Michel, P.; Pham, M.-H. Chronicles of a science diplomacy initiative on climate change. Sci. Dipl. 2018, 7, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Camilla Hodgson, COP27 Ends in Tears and Frustration: ‘The World Will Not Thank Us’, Financial Times. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/03d7609b-decc-40fc-8029-a6cdebb11752 (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- OECD. Effective Carbon Rates 2018: Pricing Carbon Emissions through Taxes and Emissions Trading; OECD Series on Carbon Pricing and Energy Taxation; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission, Statement by President von der Leyen on the Outcome of COP27. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_22_7043 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Ventriss, C. The Challenge for Public Administration (and Public Policy) in an Era of Economic Crises… or the Relevance of Cognitive Politics in a Time of Political Involution. Adm. Theory Prax. 2010, 32, 402–428. [Google Scholar]

- Tavoni, A.; Dannenberg, A.; Kallis, G.; Löschel, A. Inequality, communication, and the avoidance of disastrous climate change in a public goods game. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11825–11829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, J. The History of Global Climate Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, W.; Stockwell, C.; Flachsland, C.; Oberthür, S. The architecture of the global climate regime: A top-down perspective. Clim. Policy 2010, 10, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, G.; Rayner, S. Time to ditch Kyoto. Nature 2007, 449, 973–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, D. Plan B for Copenhagen. Nature 2009, 461, 342–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.J. Climate Governance at the Crossroads: Experimenting with a Global Response after Kyoto; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Diringer, E. Letting go of Kyoto. Nature 2011, 479, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.H. From global to polycentric climate governance. Clim. Law 2011, 2, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirix, J.; Peeters, W.; Eyckmans, J.; Jones, P.T.; Sterckx, S. Strengthening bottom-up and top-down climate governance. CSlimate Policy 2013, 13, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.F.; Sterner, T.; Wagner, G. A balance of bottom-up and top-down in linking climate policies. Nat. Climate Chang. 2014, 4, 1064–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.M. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail; Management of Innovation and Change Series; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, A.D., Jr. The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993; pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Sabel, C.; Zeitlin, J. Learning from difference: The new architecture of experimentalist in the European Union. In Experimentalist Governance in the European Union: Towards a New Architecture; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sabel, C.F.; Zeitlin, J. Experimentalism in the EU: Common ground and persistent differences. Regul. Gov. 2012, 6, 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, S.; Börzel, T.A. Experimentalist governance: An introduction. Regul. Gov. 2012, 6, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, S. Why Cooperate?: The Incentive to Supply Global Public Goods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 74–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, S.; Buzan, B. Great power management in international society. Chin. J. Int. Politics 2016, 9, 181–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodansky, D. The Durban Platform Negotiations: Goals and Options. Harv. Proj. Clim. Agreem. Viewp. 2012. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2102994 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Meyer, L.H.; Roser, D. Climate justice and historical emissions. Crit. Rev. Int. Soc. Political Philos. 2010, 13, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beron, K.J.; Murdoch, J.C.; Vijverberg WP, M. Why cooperate public goods, economic power, and the Montreal Protocol. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2003, 85, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coninck, H.; Fischer, C.; Newell, R.G.; Ueno, T. International technology-oriented agreements to address climate change. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer, 14th ed.; 2022; Article 4: Control of Trade with Non-Parties. Available online: https://ozone.unep.org/sites/default/files/Handbooks/MP-Handbook-2020-English.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Overdevest, C.; Zeitlin, J. Experimentalism in transnational forest governance: Implementing European Union forest law enforcement, governance and trade (FLEGT) voluntary partnership agreements in Indonesia and Ghana. Regul. Gov. 2018, 12, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner-Burton, E.M.; Victor, D.G.; Lupu, Y. Political science research on international law: The state of the field. Am. J. Int. Law 2012, 106, 47–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhaus, W. Climate clubs: Overcoming free-riding in international climate policy. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 1339–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelfsema, M.; van Soest, H.L.; Harmsen, M.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Bertram, C.; den Elzen, M.; Höhne, N.; Iacobuta, G.; Krey, V.; Kriegler, E. Taking stock of national climate policies to evaluate implementation of the Paris Agreement. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinken, A.J. The United States Officially Rejoins the Paris Agreement 2021. Available online: https://www.state.gov/the-united-states-officially-rejoins-the-paris-agreement (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Kim, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Matsuoka, S. Environmental and economic effectiveness of the Kyoto Protocol. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trump, D. Statement by President Trump on the Paris Climate Accord, 1 June 2017. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/statement-president-trump-paris-climate-accord/ (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Kompas, T.; Pham, V.H.; Che, T.N. The effects of climate change on GDP by country and the global economic gains from complying with the Paris climate accord. Earth’s Future 2018, 6, 1153–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, E. Analysis: U.S. Role in the Paris Agreement. Climate Interactive. 27 April 2017. Available online: https://www.climateinteractive.org/analysis/us-role-in-paris/ (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Laffoley, D.; Baxter, J.M. Ocean Connections: An Introduction to Rising Risks from a Warming, Changing Ocean. IUCN 2018. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/47718 (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Dai, H.C.; Zhang, H.B.; Wang, W.T. The impacts of US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on the carbon emission space and mitigation cost of China, EU, and Japan under the constraints of the global carbon emission space. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2017, 8, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.B.; Dai, H.C.; Lai, H.X.; Wang, W.T. U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement: Reasons, impacts, and China’s response. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res. 2017, 8, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, D.G.; Lumkowsky, M.; Dannenberg, A. Determining the credibility of commitments in international climate policy. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allington, M.; Heeren, K. How the EU Response to the Russia-Ukraine War Can Still Accelerate Low-Carbon Transition 2022, ICF. Available online: https://www.icf.com/insights/energy/russia-ukraine-war-low-carbon-transition (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Roberts, J.T.; Weikmans, R.; Robinson, S.A.; Ciplet, D.; Khan, M.; Falzon, D. Rebooting a failed promise of climate finance. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Mitigation of Climate Change: Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg3/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Rogelj, J.; Den Elzen, M.; Höhne, N.; Fransen, T.; Fekete, H.; Winkler, H.; Schaeffer, R.; Sha, F.; Riahi, K.; Meinshausen, M. Paris Agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2 C. Nature 2016, 534, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Aggregate Effect of the Intended Nationally Determined Contributions: An Update, Synthesis Report by the Secretariat 2016. Available online: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2016/cop22/eng/02.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Rogelj, J.; Fricko, O.; Meinshausen, M.; Krey, V.; Zilliacus, J.J.; Riahi, K. Understanding the origin of Paris Agreement emission uncertainties. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnet, Y.; Van Asselt, H.; Cavalheiro, G.; Rocha, M.; Bisiaux, A.; Cogswell, N. Designing the Enhanced Transparency Framework, Part 2: Review Under the Paris Agreement. World Resources Institute. 2017. Available online: https://www.wri.org/sites/default/files/designing-enhanced-transparency-framework-part-2-review-under-paris-agreement.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Benveniste, H.; Boucher, O.; Guivarch, C.; Le Treut, H.; Criqui, P. Impacts of nationally determined contributions on 2030 global greenhouse gas emissions: Uncertainty analysis and distribution of emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 014022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauw, W.P.; Klein, R.J.; Mbeva, K.; Dzebo, A.; Cassanmagnago, D.; Rudloff, A. Beyond headline mitigation numbers: We need more transparent and comparable NDCs to achieve the Paris Agreement on climate change. Clim. Chang. 2018, 147, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graichen, J.; Cames, M.; Schneider, L. Categorization of INDCs in the light of Art. 6 of the Paris Agreement Discussion Paper, October 2016. Available online: http://www.carbon-mechanisms.de/fileadmin/media/dokumente/Publikationen/Studie/Studie_2016_Categorization_of_INDCs_Paris_Agreement.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- German Development Institute. Available online: http://klimalog.die-gdi.de (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Hood, M. Five Reasons COP25 Climate Talks Failed. PHYSORG. 25 December 2019. Available online: https://phys.org/news/2019-12-cop25-climate.html (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Dupuy, P.M. Soft law and the international law of the environment. Mich. J. Int’l L 1990, 12, 420. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, S.; Dannenberg, A. The decision to link trade agreements to the supply of global public goods. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2022, 9, 273–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Effective Carbon Rates 2021: Pricing Carbon Emissions through Taxes and Emissions Trading; OECD Series on Carbon Pricing and Energy Taxation; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, A.; Parra, G.; Chávez, A. The Evolution of Patent Thicket in Hybrid Vehicles, Commoners and the Changing Commons: Livelihoods, Environmental Security, and Shared Knowledge. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of the Commons, Online, 3–7 June 2013; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, J.; Xu, Y.; Weller, P. Norm entrepreneurship and diffusion ‘from below’ in international organisations: How the competent performance of vulnerability generates benefits for small state. Rev. Int. Stud. 2019, 45, 647–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, K.W.; Green, J.F.; Keohane, R.O. Organizational ecology and institutional change in global governance. Int. Organ. 2016, 70, 247–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keohane, R.O.; Victor, D.G. The regime complex for climate change. Perspect. Politics 2011, 9, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosens, B.A.; Ruhl, J.B.; Soininen, N.; Gunderson, L. Designing law to enable adaptive governance of modern wicked problems. Vand. L. Rev. 2020, 73, 1687. [Google Scholar]

- Young, O.R. Grand Challenges of Planetary Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Goulder, L.H.; Parry, I.W.H. Instrument choice in environmental policy. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2008, 2, 152–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, E.; Scott, W.A.; Jaccard, M. Designing flexible regulations to mitigate climate change: A cross-country comparative policy analysis. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Águeda Corneloup, I.; Mol, A.P. Small island developing states and international climate change negotiations: The power of moral “leadership”. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2014, 14, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R. International Governance: Protecting the Environment in a Stateless Society; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Young, O.R. The Institutional Dimensions of Environmental Change: Fit, Interplay, and Scale; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 122–125. [Google Scholar]

| High Capability | Low Capability | |

|---|---|---|

| High Motivation | Leader | Reserve Force |

| Low Motivation | Waverer | Obscurity |

| Character | Mitigation Responsibility | Adaptation Responsibility | Credibility | Open-Ended Goal | Original Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leader | Energy, agriculture, IPPU, LULUCF, waste; transparency report every 2 years | Loss and damage fund; transparency report every 2 years | Domestic Review every 4 years | NDC every 5 years; carbon neutrality achieved around 2050 | Annex I countries (e.g., Switzerland) and some non-Annex I countries (e.g., Uruguay) |

| Reserve Force | One specific mitigation field every 5 years with the same measurement caliber as Leader; transparency report every 2 years | Transparency report every 2 years | Different level of review every 4 years based on the results of NCSA and CfT | NDC every 5 years; carbon neutrality around 2050 | Non-Annex I countries (e.g., China) |

| Waverer | Transparency report every 2 years | Transparency report every 2 years | Central review every 4 years | NDC every 5 years; FMCP every 2 years; carbon neutrality around 2050 | Annex I countries (e.g., Australia) and some non-Annex I countries (e.g., Singapore) |

| Obscurity | Transparency report every 2 years | Desk review every 4 years | NDC every 5 years; FMCP every 2 years; carbon neutrality around 2050 | Non-Annex I countries (e.g., Afghanistan) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, G.; Yu, H. Rescuing the Paris Agreement: Improving the Global Experimentalist Governance by Reclassifying Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043207

Qin G, Yu H. Rescuing the Paris Agreement: Improving the Global Experimentalist Governance by Reclassifying Countries. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043207

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Geng, and Hanzhi Yu. 2023. "Rescuing the Paris Agreement: Improving the Global Experimentalist Governance by Reclassifying Countries" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043207