Adolescents as Ambassadors in Substance Abuse Awareness Programs: Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Program Design

2.2. Settings

2.3. Participants

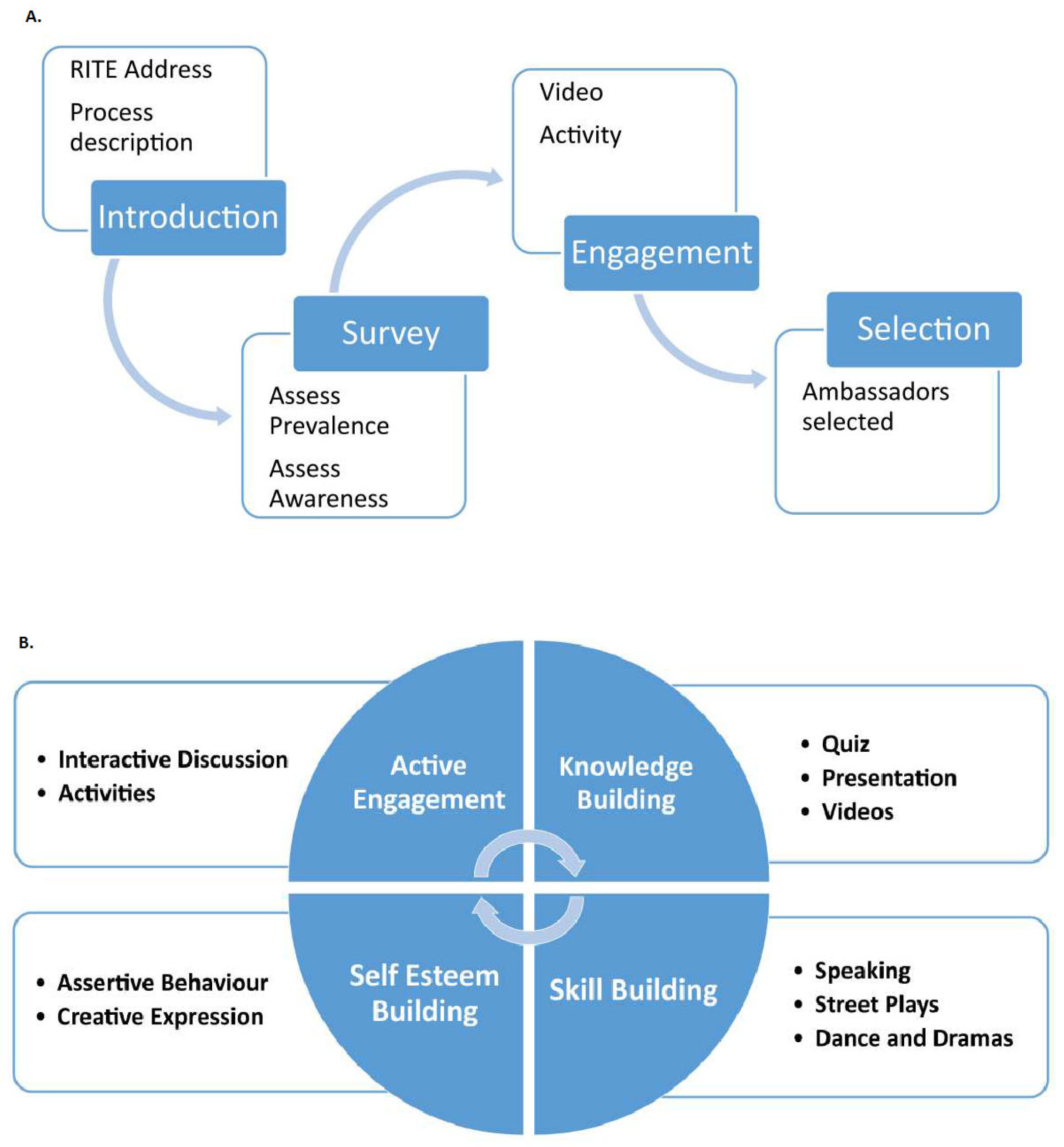

2.4. Program Phases

2.4.1. Phase 1: Selection of Ambassadors

2.4.2. Phase 2: Training of Ambassadors

2.4.3. Phase 3: Dissemination to School Community

2.4.4. Phase 4: Extension to Village Community

2.5. Educational Modalities

2.6. Follow-Up Programs

2.7. Survey Instrument

2.8. Statistical Methods

3. Results

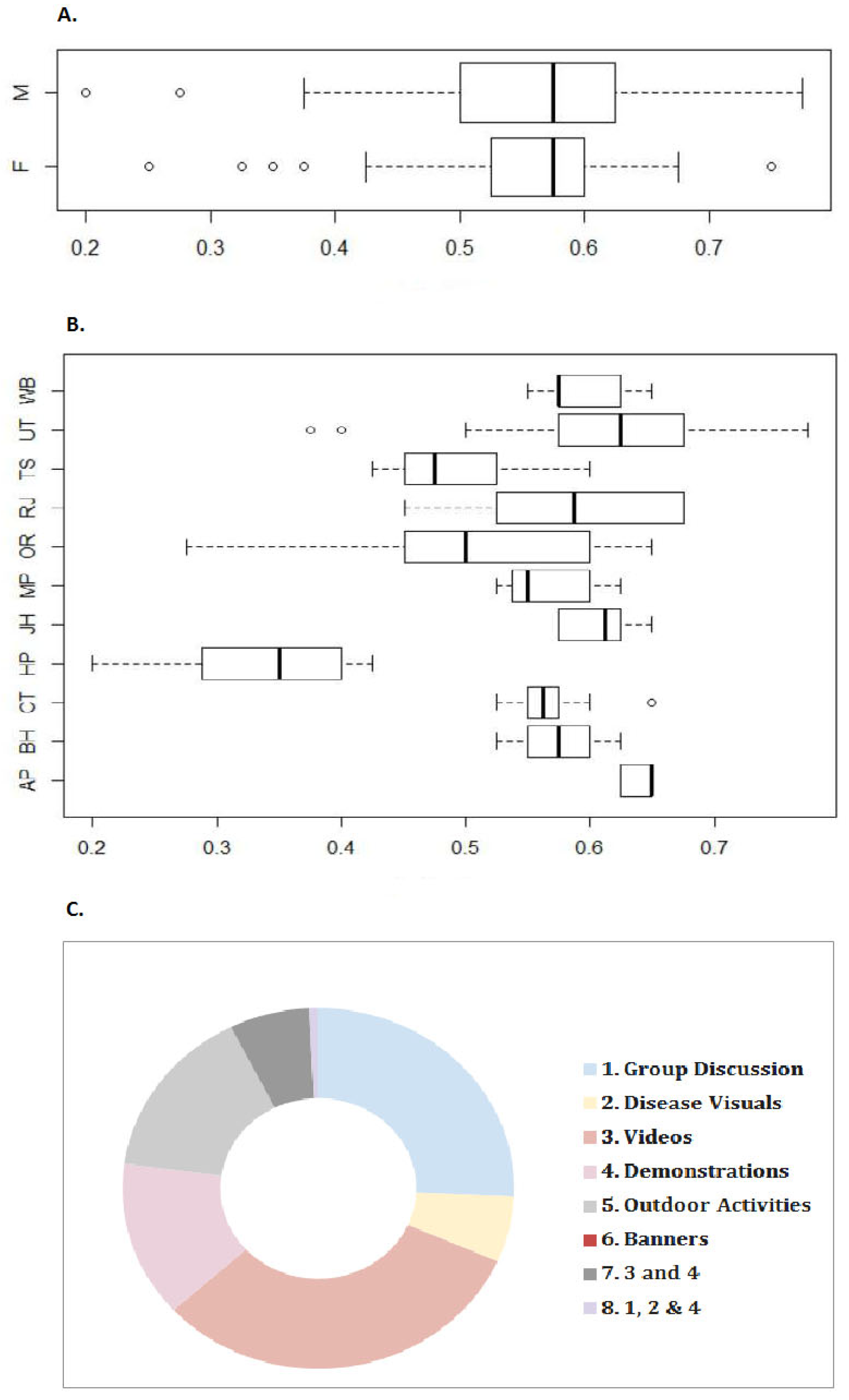

3.1. Substance Abuse Prevalence Estimates

3.2. Self-Esteem

3.3. Self-Esteem and Social Support Perceptions

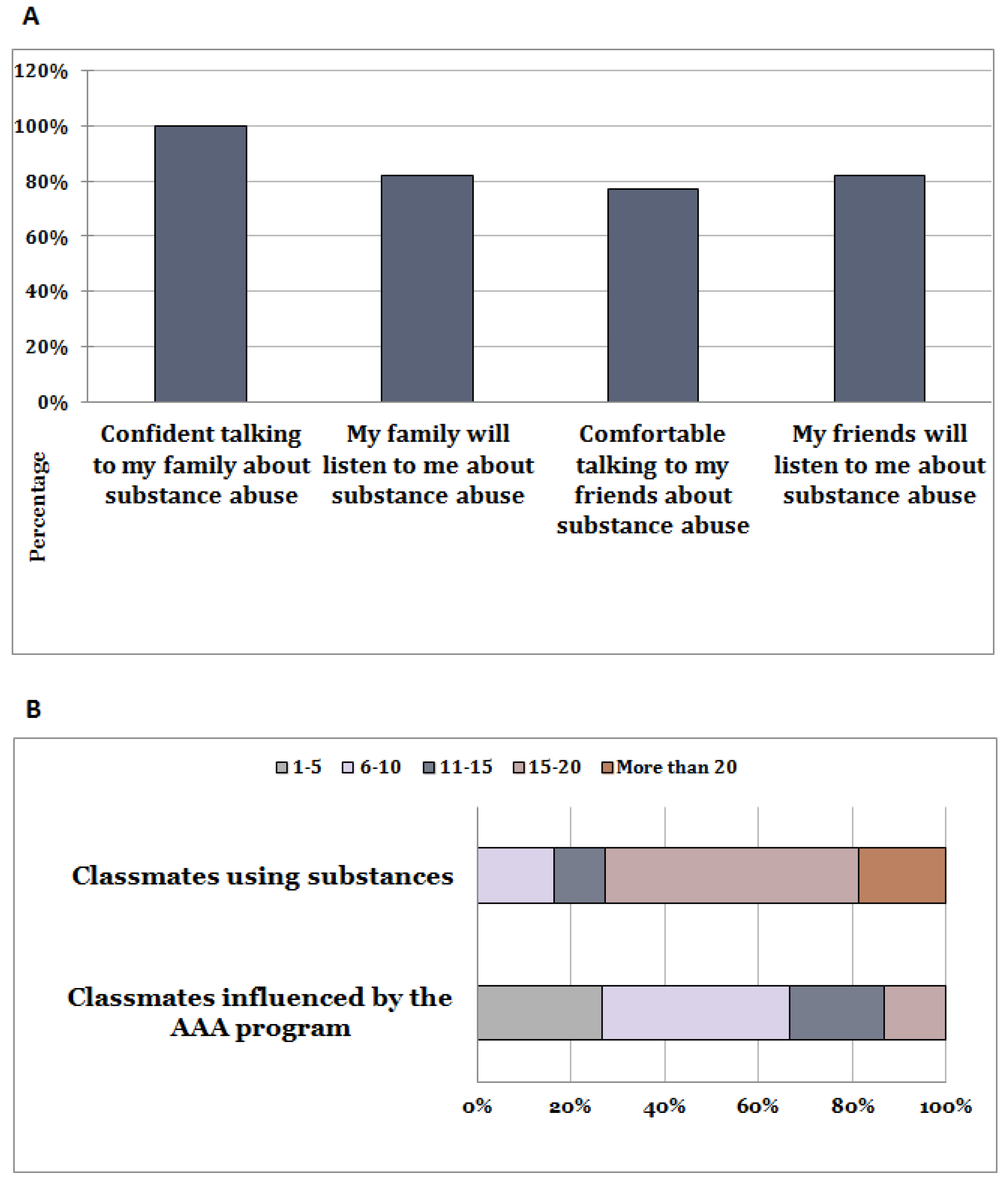

3.4. Peer and Social Influence

3.5. Learning Methods and Perceived Prevalence

4. Discussion

4.1. Change in Ambassador’s Self-Esteem

4.2. Peer Influence

4.3. Family Communication

4.4. Sustainability, Replicability, and Scalability

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Collin, J.; Casswell, S. Alcohol and the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet 2016, 387, 2582–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedotov, Y. World Drug Report 2012; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC): New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan, S. Community Approach to Alcoholism Treatment: An Exploratory/Evaluative Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Madras, Chennai, India, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, GoI. National Family Health Survey [NFHS-5] 2019-21; International Institute for Population Sciences: Mumbai, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office. Sustainable Development Goals Progress Report 2021; National Indicator Framework Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eashwar, V.M.A.; Umadevi, R.; Gopalakrishnan, S. Alcohol consumption in India—An epidemiological review. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R. Alcohol use on the rise in India. Lancet 2009, 373, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, A.; Minz, S.; Manohari, G.P.; Thavamani; George, K.; Arun, R.; Vinodh, A. Community perspectives on alcohol use among a tribal population in rural southern India. Natl. Med. J. India 2016, 28, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Spear, L. The Teenage Brain. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, K.A. Alcohol consumption and brain health. BMJ 2017, 357, j2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bellis, M.D.; Clark, D.B.; Beers, S.R.; Soloff, P.H.; Boring, A.M.; Hall, J.; Kersch, A.; Keshaven, M.S. Hippocampal volume in adolescent-onset alcohol use disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrecht, M.; Häfner, H. Substance abuse and the onset of schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 1996, 40, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuckit, M.A. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet 2009, 373, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aswathy, S.; Syama, S.; Georgy, S.; Mathew, M.; Mohandas, S.; Menon, V.; Numpelil, M. Tobacco use and exposure to second-hand smoke among high school students in Ernakulum district, Kerala: A cross-sectional study. Public Health Pract. 2021, 2, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M. Family and School Influences on Cognitive Development. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1985, 26, 683–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, S.R.; Felitti, V.J.; Dong, M.; Chapman, D.P.; Giles, W.H.; Anda, R.F. Childhood Abuse, Neglect, and Household Dysfunction and the Risk of Illicit Drug Use: The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, N.G.; DiNotto, D.M. Mental health & substance use: Challenges for serving older adults. Indian J. Med. Res. 2013, 138, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Merchant, H.; Pandya, P. Cultural determinants responsible for development of alcohol dependence—A cross-sectional observational hospital based study. IJIMS 2015, 2, 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, V. Wife-beating in rural South India: A qualitative and econometric analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 1997, 44, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.; Mapp, K. A New Wave of Evidence: The Impact of Family, School, Community Connections on Student Achievement; Southwest Educational Development: Austin, TX, USA, 2002; p. 239. [Google Scholar]

- Reeb, B.T.; Chan, S.Y.S.; Conger, K.J.; Martin, M.J.; Hollis, N.D.; Serido, J.; Russell, S.T. Prospective Effects of Family Cohesion on Alcohol-Related Problems in Adolescence: Similarities and Differences by Race/Ethnicity. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 44, 1941–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Warner, L.A. Parent-Adolescent Conflict, Family Cohesion, and Self-Esteem Among Hispanic Adolescents in Immigrant Families: A Comparative Analysis. Fam. Relat. 2015, 64, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostelecky, K.L. Parental attachment, academic achievement, life events and their relationship to alcohol and drug use during adolescence. J. Adolesc. 2005, 28, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, T.P.; Eaves, L.J.; Lichtenstein, P.; Neale, M.C.; Svensson, A.; Latendresse, S.; Långström, N.; Strauss, J.F. Fetal and Maternal Genes’ Influence on Gestational Age in a Quantitative Genetic Analysis of 244,000 Swedish Births. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 178, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimura, A.; Takaesu, Y.; Nakai, Y.; Murakoshi, A.; Ono, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Kusumi, I.; Inoue, T. Childhood parental bonding affects adulthood trait anxiety through self-esteem. Compr. Psychiatry 2017, 74, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smorti, M.; Guarnieri, S. The Parental Bond and Alcohol Use Among Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Drinking Motives. Subst. Use Misuse 2015, 50, 1560–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Ryzin, M.J.; Fosco, G.M.; Dishion, T.J. Family and peer predictors of substance use from early adolescence to early adulthood: An 11-year prospective analysis. Addict. Behav. 2012, 37, 1314–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshri, A.; Carlson, M.W.; Kwon, J.A.; Zeichner, A.; Wickrama, K.K.A.S. Developmental Growth Trajectories of Self-Esteem in Adolescence: Associations with Child Neglect and Drug Use and Abuse in Young Adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 46, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riquelme, M.; Garcia, O.F.; Serra, E. Psychosocial maladjustment in adolescence: Parental socialization, self-esteem, and substance use. An. Psicol. 2018, 34, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, E.M.; McDermott, R.J.; Holcomb, D.R.; Marty, P.J. The relationship between youth substance use and area-specific self-esteem. J. Sch. Health 1993, 63, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.; Young, M.; Pearson, R.; Penhollow, T.M.; Hernandez, A. Area Specific Self-Esteem, Values, and Adolescent Substance Use. J. Drug Educ. 2008, 38, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneberger, A.K.; Mushonga, D.R.; Preston, A.M. Peer Influence and Adolescent Substance Use: A Systematic Review of Dynamic Social Network Research. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2020, 6, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C.L.; Williams, C.L.; Komro, K.A.; Veblen-Mortenson, S.; Stigler, M.H.; Munson, K.A.; Farbakhsh, K.; Jones, R.M.; Forster, J.L. Project Northland: Long-term outcomes of community action to reduce adolescent alcohol use. Health Educ. Res. 2002, 17, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotrean, L.M.; Dijk, F.; Mesters, I.; Ionut, C.; De Vries, H. Evaluation of a peer-led smoking prevention programme for Romanian adolescents. Health Educ. Res. 2010, 25, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, A.; Saha, S. Alcohol use disorders in adolescents. Pediatr. Ver. 2013, 34, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; p. 478. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639 (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Aldridge, S.; Halpern, D.; Fitzpatrick, S. Social Capital; Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nasha Mukt Bharat Abhiyaan|National Portal of India. Available online: https://www.india.gov.in/spotlight/nasha-mukt-bharat-abhiyaan (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Kapoor, N.J.; Maurya, A.P.; Raman, R.; Govind, K.; Nedungadi, P. Digital India eGovernance Initiative for Tribal Empowerment: Performance Dashboard of the Ministry of Tribal Affairs; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 190, pp. 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutjahr, G.; Nair, A.; Menon, R.; Nedungadi, P. Technology for Monitoring and Coordinating an After-School Program in Remote Areas of India. In Proceedings of the IEEE 10th International Conference on Technology for Education, Goa, India, 9–11 December 2019; pp. 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komro, K.A. How did Project Northland reduce alcohol use among young adolescents? Analysis of mediating variables. Health Educ. Res. 2001, 16, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saranya, T.S.; Deb, S. Resilience Capacity and Support Function of Paniya Tribal Adolescents in Kerala and Its Association with Demographic variables. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2015, 2, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedungadi, P.; Raman, R.; Menon, R.; Mulki, K. AmritaRITE: A Holistic Model for Inclusive Education in Rural India. In Children and Sustainable Development: Ecological Education in a Globalized World; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseinpoor, Z.; Khosrojavid, M.; Kafi, M. The Effect of Communication Training Skills on Self-Efficacy and Social Anxiety of Students. J. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 11, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutjahr, G.; Renji, B.; Menon, R.; Nedungadi, P. Statistical consistency of substance-abuse prevalence assessments in tribal areas of Chhattisgarh. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2336, 040010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. Frugal innovation and sustainable business models. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE), integrativehealthpartners.org. 1965. Available online: https://integrativehealthpartners.org/downloads/ACTmeasures.pdf#page=61 (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Om Prakash, S. Substance Use in India–Policy Implications. Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 62, 111. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/indianjpsychiatry/Fulltext/2020/62020/Substance_use_in_India___Policy_implications.1.aspx (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- National Institute of Public Coopration and Child Development (NIPCCD). Module on SABLA; Ministry of Women and Child Development, GoI: New Delhi, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jiloha, R.C. Prevention, Early Intervention, and Harm Reduction of Substance Use in Adolescents. 2017. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5418996/ (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Hans, V.B. Social Capital for Holistic Development: Issues and Challenges in India. 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Vedamani-Hans/publication/266261256_Social_Capital_for_Holistic_Development_Issues_and_Challenges_in_India/links/5551ff9e08ae6943a86d6906/Social-Capital-for-Holistic-Development-Issues-and-Challenges-in-India.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Uemura, M. Community Participation in Education: What Do We Know? World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Erozkan, A. The effect of communication skills and interpersonal problem solving skills on social self-efficacy. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2013, 13, 739–745. [Google Scholar]

- Debbie, Z.; Michael, S. Teaching to Empower: Taking Action to Foster Student Agency, Self-Confidence; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wodtke, G.T.; Harding, D.J.; Elwert, F. Neighborhood Effects in Temporal Perspective: The Impact of Long-Term Exposure to Concentrated Disadvantage on High School Graduation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2011, 76, 713–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, G.J.; Harrison, S.; Caldwell, D.M.; Hickman, M.; Campbell, R. Peer-led interventions to prevent tobacco, alcohol and/or drug use among young people aged 11–21 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 2016, 111, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanemann, U. Literacy for Student’s Illiterate Parents, Iran; UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning: Hamburg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, M.; Provost, M.A. Resilience in adolescents: Protective role of social support, coping strategies, self-esteem, and social activities on experience of stress and depression. J. Youth Adolesc. 1999, 28, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusby, J.C.; Light, J.M.; Crowley, R.; Westling, E. Influence of parent–youth relationship, parental monitoring, and parent substance use on adolescent substance use onset. J. Fam. Psychol. 2018, 32, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajayan, S.; Menon, G.H.R.; Gutjahr, G.; Nedungadi, P. Cost-Effectiveness of a Substance-Abuse Prevention Program in Tribal Areas of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand. Lect. Notes Netw. Syst. 2022, 286, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Nair, V.K.; Prakash, V.; Patwardhan, A.; Nedungadi, P. Green-Hydrogen Research: What Have We Achieved, and Where Are We Going? Bibliometrics Analysis. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 9242–9260. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S235248472201321X (accessed on 13 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Vinuesa, R.; Nedungadi, P. Bibliometric Analysis of SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 Studies from India and Connection to Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achuthan, K.; Nair, V.K.; Kowalski, R.; Ramanathan, S.; Raman, R. Cyberbullying Research—Alignment to Sustainable Development and Impact of COVID-19: Bibliometrics and Science Mapping Analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 140, 107566. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563222003867 (accessed on 13 January 2023). [CrossRef]

| State | Boys | Girls | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | >50% | <50% | None | All | >50% | <50% | None | |

| AP | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| BH | 0 | 0 | 33 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 83 |

| CT | 0 | 0 | 64 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| HP | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| JH | 0 | 0 | 10 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| MP | 0 | 0 | 44 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| OR | 0 | 38 | 24 | 38 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 86 |

| RJ | 0 | 62 | 12 | 25 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 62 |

| TS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| UT | 59 | 29 | 12 | 0 | 71 | 18 | 12 | 0 |

| WB | 0 | 0 | 55 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Rank Correlation | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Self-esteem | 0.195 | 0.027 |

| Having at least one teacher I can talk to | 0.337 | <0.001 |

| There is at least one adult or parent that I had to talk to | 0.218 | 0.016 |

| Using chewing tobacco | 0.146 | 0.098 |

| Using other substances | −0.139 | 0.116 |

| Boys in the village are using alcohol or other substances | −0.279 | 0.001 |

| Girls in the village are using alcohol or other substances | 0.008 | 0.924 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nedungadi, P.; Menon, R.; Gutjahr, G.; Raman, R. Adolescents as Ambassadors in Substance Abuse Awareness Programs: Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Effects. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043491

Nedungadi P, Menon R, Gutjahr G, Raman R. Adolescents as Ambassadors in Substance Abuse Awareness Programs: Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Effects. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043491

Chicago/Turabian StyleNedungadi, Prema, Radhika Menon, Georg Gutjahr, and Raghu Raman. 2023. "Adolescents as Ambassadors in Substance Abuse Awareness Programs: Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Effects" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043491

APA StyleNedungadi, P., Menon, R., Gutjahr, G., & Raman, R. (2023). Adolescents as Ambassadors in Substance Abuse Awareness Programs: Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Effects. Sustainability, 15(4), 3491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043491