Impact of Entrepreneurial Team Contractual Governance on New Venture Resilience: The Mediating Role of Resource Bricolage

Abstract

1. Introduction

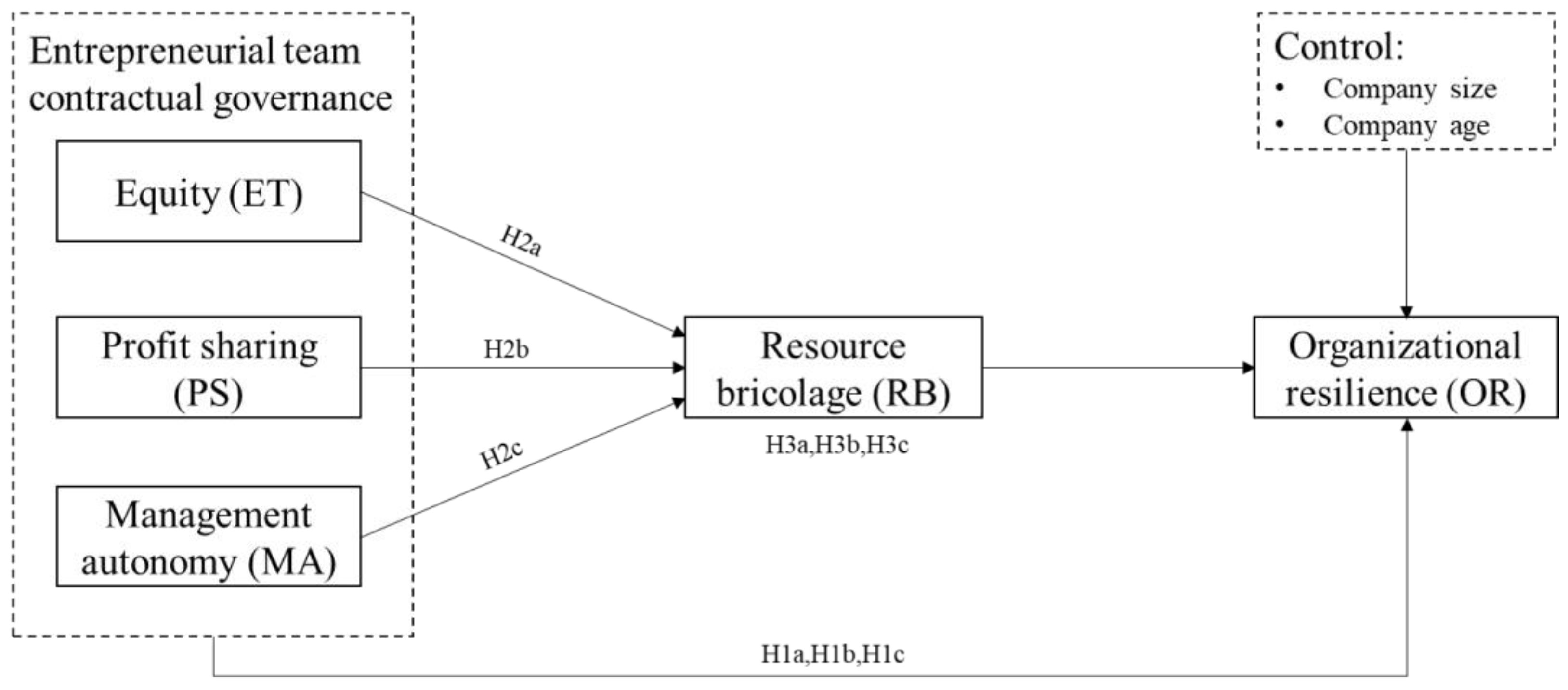

2. Theoretical Background and Model Hypothesis

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.2. Entrepreneurial Team Contractual Governance and New Venture Resilience

2.3. Entrepreneurial Team Contractual Governance and Resource Bricolage

2.4. The Mediating Role of Resource Bricolage

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Design

3.2. Survey Implementation

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Analysis

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analyses

4.3. Model Verification

4.4. Importance–Performance Map Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Item | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Equity governance (ET) | ET 1 | The distribution and change in equity of each team member reflects their resource and ability advantages |

| ET 2 | When allocating equity, we not only consider the capital contribution, technology, or patent investment from each team member, but also consider their experience and social capital | |

| ET 3 | When allocating equity, we not only consider the existing capital and technology investment of each team member but also consider their resource and ability advantages at different stages of the entrepreneurship process | |

| ET 4 | Considering the development needs of the organization, we left room for future equity adjustment | |

| Profit-sharing governance (PS) | PS 1 | Our income policy reflects the efforts of each team member |

| PS 2 | Our income policy considers the different performance and contributions of each team member | |

| PS 3 | We have short-term incentive policies, such as commission, year-end reward, subsidy, etc. | |

| Management Autonomy governance (MA) | MA 1 | Team members know the financial and operating conditions of our organization |

| MA 2 | Each team member participates in the operation and management activities of our organization based on the division of roles | |

| MA 3 | Each team member has full decision-making power | |

| MA 4 | Team members can fully express their opinions if they disagree on a strategic decision of the organization | |

| MA 5 | Each team member handles the work of the department independently with the authorization of management | |

| Resource Bricolage (RB) | RB1 | We are confident in our ability to find workable solutions to new challenges by using our existing resources |

| RB 2 | We gladly take on a broader range of challenges than others with our resources would be able to | |

| RB 3 | We use any existing resource that seems useful to respond to a new problem or opportunity | |

| RB 4 | We deal with new challenges by applying a combination of our existing resources and other resources inexpensively available to us | |

| RB 5 | When dealing with new problems or opportunities, we take action by assuming that we will find a workable solution | |

| RB 6 | By combining our existing resources, we take on a surprising variety of new challenges | |

| RB 7 | When we face new challenges, we put together workable solutions from our existing resources | |

| RB 8 | We combine resources to accomplish new challenges for which the resources were not originally intended | |

| Organizational resilience (OR) | OR1 | My organization stands straight and preserves its position |

| OR2 | My organization is successful in generating diverse solutions | |

| OR5 | My organization is agile in taking required action when needed | |

| OR6 | My organization is a place where all employees are sufficiently engaged to do what is required from them | |

| OR7 | My organization is successful in acting as a whole with all of its employees | |

| OR8 | My organization shows resistance to the end in order to not lose | |

| OR9 | My organization does not give up and continues on its path |

Appendix B

| Characteristics | N = 549 | Percent (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Gender | Male | 335 | 61.02 |

| Female | 214 | 38.98 | ||

| Age | 21–30 | 132 | 24.04 | |

| 31–40 | 318 | 57.92 | ||

| 41–50 | 82 | 14.94 | ||

| 51 or above | 17 | 3.10 | ||

| Education | High school or below | 26 | 4.74 | |

| Diploma | 403 | 73.41 | ||

| Undergraduate | 122 | 22.22 | ||

| Postgraduate | 8 | 1.46 | ||

| Position | Founder | 261 | 47.54 | |

| Stakeholder | 56 | 10.20 | ||

| Top manager | 232 | 42.26 | ||

| Company age | Below 3 years | 163 | 29.69 | |

| 3–5 | 199 | 36.25 | ||

| 5–8 | 187 | 34.06 | ||

| Company size | 2–20 | 233 | 42.44 | |

| 21–50 | 135 | 24.59 | ||

| 51–200 | 140 | 25.50 | ||

| Above 201 | 41 | 7.47 | ||

References

- Penrose, E.T. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, T.; Nelson, R.E. Creating Something from Nothing: Resource Construction through Entrepreneurial Bricolage. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 329–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, J.A.; Spinelli, S.; Tan, Y. New Venture Creation: Entrepreneurship for the 21st Century; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, L.L.; Borini, F.M.; Pereira, R.M. Bricolage as a path towards organizational innovativeness in times of market and technological turbulence. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 13, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsgaard, S.; Müller, S.; Welter, F. It’s right nearby: How entrepreneurs use spatial bricolage to overcome resource constraints. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2020, 33, 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Schoonhoven, C.B. Organizational Growth: Linking Founding Team, Strategy, Environment, and Growth Among U.S. Semiconductor Ventures, 1978–1988. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Aldrich, H.E. Who’s the Boss? Explaining Gender Inequality in Entrepreneurial Teams. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 79, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amason, A.C. Distinguishing the effects of functional and dysfunctional conflict on strategic decision making: Resolving a paradox for top management teams. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmieleski, K.M.; Ensley, M.D. A contextual examination of new venture performance: Entrepreneur leadership behavior, top management team heterogeneity, and environmental dynamism. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 865–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Barney, J.B. How do entrepreneurs organize firms under conditions of uncertainty? J. Manag. 2005, 31, 776–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, S.; Hambrick, D.C. Top-Management-Team Tenure and Organizational Outcomes: The Moderating Role of Managerial Discretion. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, G.P. Collective Cognition: When Entrepreneurial Teams, Not Individuals, Make Decisions. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2007, 31, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Dai, J.; Zeng, C. A study on the evolution and governance of entrepreneurial team in a human capital perspecive. Acad. Res. J. 2013, 10, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Z.R.; Qi, Z.; Xiang, W.Z. Can Entrepreneurial Team Contractual Governance Really Help the New Venture Performance? A Moderated Mediation Model. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2018, 21, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cooney, T.M. What is an entrepreneurial team? Int. Small Bus. J. 2005, 23, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Y.; Wu, Y.J.; Wang, Y.-M. How Does Entrepreneurial Team Relational Governance Promote Social Start-Ups’ Organizational Resilience? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M.W.; Luo, Y. Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Su, Z.; Tao, Y.; Nguyen, B.; Xia, F. Entrepreneurial bricolage and its effects on new venture growth and adaptiveness in an emerging economy. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2019, 37, 1141–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyard, J.; Baker, T.; Steffens, P.; Davidsson, P. Bricolage as a Path to Innovativeness for Resource-Constrained New Firms. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 31, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. The Collapse of Sensemaking in Organizations: The Mann Gulch Disaster. Adm. Sci. Q. 1993, 38, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desa, G.; Basu, S. Optimization or Bricolage? Overcoming Resource Constraints in Global Social Entrepreneurship. Strat. Entrep. J. 2013, 7, 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Department of Management and Human Resources, School of Business, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA; Aldrich, H.E.; Department of Sociology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA. Bricolage and Resource-Seeking: Improvisational Responses to Dependence in Entrepreneurial Firms. Unpublished work. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A.D. Adapting to environmental jolts. Adm. Sci. Q. 1982, 27, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, D.M.; Landon, L.B.; Maynard, M.T. Extending the Conversation: Employee Resilience at the Team Level. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 9, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.B.; Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. Recent developments in team resilience research in elite sport. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 16, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.A. Benchmarking Organizational Resilience: A Cross-Sectional Comparative Research Study; New Jersey City University: Jersey City, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Xiang, P. Crisis process management: How to improve organizational resilience? Foreign Econ. Manag. 2020, 43, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Naderpajouh, N.; Yu, D.J.; Aldrich, D.P.; Linkov, I.; Matinheikki, J. Engineering meets institutions: An interdisciplinary approach to the management of resilience. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2018, 38, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C. Upper Echelons Theory: An Update. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, M.-D.; Sin, H.-P.; Yiong, L.-P. Effects of team inputs and intrateam processes on perceptions of team viability and member satisfaction in nascent ventures. Strat. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, Q.; Zott, C. Exploring the affective underpinnings of dynamic managerial capabilities: How managers’ emotion regulation behaviors mobilize resources for their firms. Strat. Manag. J. 2018, 40, 28–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantur, D.; Iseri-Say, A. Organizational resilience: A conceptual integrative framework. J. Manag. Organ. 2012, 18, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnick, B.J.; Murnieks, C.Y.; McMullen, J.S.; Brooks, W.T. Passion for entrepreneurship or passion for the product? A conjoint analysis of angel and VC decision-making. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, Z. Organizational Ambidexterity: Towards a Multilevel Understanding. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 597–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanjian, R.K.; Drazin, R. A stage-contingent model of design and growth for technology based new ventures. J. Bus. Ventur. 1990, 5, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Bogner, W.C. Technology strategy and software new ventures’ performance: Exploring the moderating effect of the competitive environment. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 135–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Di Domenico, M.; Haugh, H.; Tracey, P. Social Bricolage: Theorizing Social Value Creation in Social Enterprises. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2010, 34, 681–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantur, D.; Say, A.I. Measuring organizational resilience: A scale development. J. Bus. Econ. Financ. 2015, 4, 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuahene-Gima, K.; Murray, J.Y. Exploratory and Exploitative Learning in New Product Development: A Social Capital Perspective on New Technology Ventures in China. J. Int. Mark. 2007, 15, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, J.M.; Senter, J.L. Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 815–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Johnson, M.D.; Anderson, E.W.; Cha, J.; Bryant, B.E. The American customer satisfaction index: Nature, purpose, and findings. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Gain more insight from your PLS-SEM results: The importance-performance map analysis. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1865–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, C.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Management of multi-purpose stadiums: Importance and performance measurement of service interfaces. Int. J. Serv. Technol. Manag. 2010, 14, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Upper Saddle River: Jersey City, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha | Convergence Validity AVE | Composite Reliability CR | Discriminant Validity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET | PS | MA | RB | OR | |||||

| ET | 4 | 0.858 | 0.701 | 0.904 | 0.837 | ||||

| PS | 3 | 0.757 | 0.676 | 0.861 | 0.616 | 0.822 | |||

| MA | 5 | 0.791 | 0.544 | 0.856 | 0.510 | 0.549 | 0.738 | ||

| RB | 8 | 0.905 | 0.600 | 0.923 | 0.509 | 0.531 | 0.604 | 0.775 | |

| OR | 7 | 0.884 | 0.591 | 0.910 | 0.443 | 0.529 | 0.530 | 0.713 | 0.769 |

| Hypotheses | Standardized Path Coefficient | Sample Mean | Standard Deviation STDEV | T Statistic | Confidence Interval CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized path coefficient | ||||||

| ET → OR | −0.003 | −0.003 | 0.041 | 0.076 | [−0.069–0.068] | 0.470 |

| PS → OR | 0.164 | 0.164 | 0.039 | 4.195 | [0.099–0.229] | *** |

| MA → OR | 0.106 | 0.105 | 0.050 | 2.103 | [0.021–0.188] | * |

| ET → RB | 0.182 | 0.183 | 0.050 | 3.608 | [0.099–0.263] | *** |

| PS → RB | 0.198 | 0.200 | 0.051 | 3.859 | [0.115–0.286] | *** |

| MA → RB | 0.403 | 0.402 | 0.056 | 7.254 | [0.308–0.493] | *** |

| RB → OR | 0.555 | 0.555 | 0.045 | 12.397 | [0.480–0.627] | *** |

| Mediation effect | ||||||

| ET → RB → OR | 0.101 | 0.101 | 0.028 | 3.576 | [0.055–0.147] | *** |

| PS → MA → OR | 0.110 | 0.111 | 0.029 | 3.731 | [0.063–0.161] | *** |

| MA → RB → OR | 0.224 | 0.224 | 0.038 | 5.823 | [0.161–0.288] | *** |

| Target Construct | Resource Bricolage | Organizational Resilience | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedent Variable | Importance | Performance | Importance | Performance | |

| Equity governance | 0.182 | 74.397 | 0.098 | 74.397 | |

| Profit-sharing governance | 0.198 | 77.069 | 0.274 | 77.069 | |

| Management autonomy governance | 0.403 | 79.287 | 0.329 | 79.287 | |

| Resource bricolage | - | - | 0.555 | 77.015 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mai, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wu, Y.J.; Dong, T.-P. Impact of Entrepreneurial Team Contractual Governance on New Venture Resilience: The Mediating Role of Resource Bricolage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043518

Mai Y, Zheng W, Wu YJ, Dong T-P. Impact of Entrepreneurial Team Contractual Governance on New Venture Resilience: The Mediating Role of Resource Bricolage. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043518

Chicago/Turabian StyleMai, Yingping, Wenzhi Zheng, Yenchun Jim Wu, and Tse-Ping Dong. 2023. "Impact of Entrepreneurial Team Contractual Governance on New Venture Resilience: The Mediating Role of Resource Bricolage" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043518

APA StyleMai, Y., Zheng, W., Wu, Y. J., & Dong, T.-P. (2023). Impact of Entrepreneurial Team Contractual Governance on New Venture Resilience: The Mediating Role of Resource Bricolage. Sustainability, 15(4), 3518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043518