Board Characteristics and Corporate Sustainability Reporting: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Contextual and Institutional Background of the Study

Corporate Sustainability Reporting (CSR) in China

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Corporate Sustainability Reporting (CSR)

3.2. Agency Theory

3.3. Resource Dependency Theory (RDT)

3.4. Legitimacy Theory

3.5. Stakeholder Theory

4. Literature and Hypotheses Development

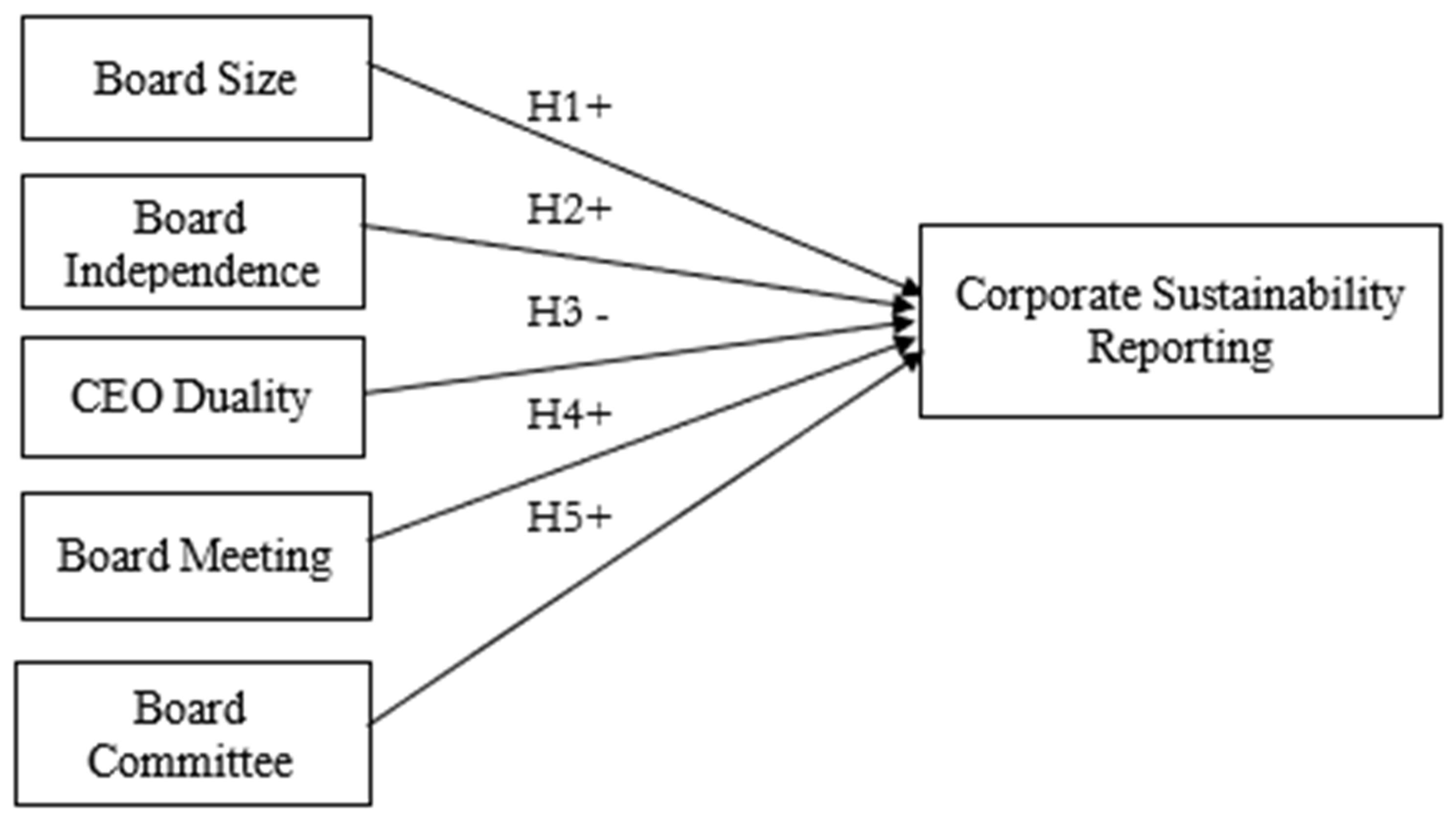

4.1. Hypotheses Development

4.1.1. Board Size and CRS

4.1.2. Board Independence and CSR

4.1.3. CEO Duality and CSR

4.1.4. Board Meetings and CSR

4.1.5. Board Committees and CSR

5. Research Methodology

5.1. Data Collection and Selection Criteria

5.2. Measurements of Variables

5.2.1. Dependent Variable

5.2.2. Independent variables

5.3. Model Specification

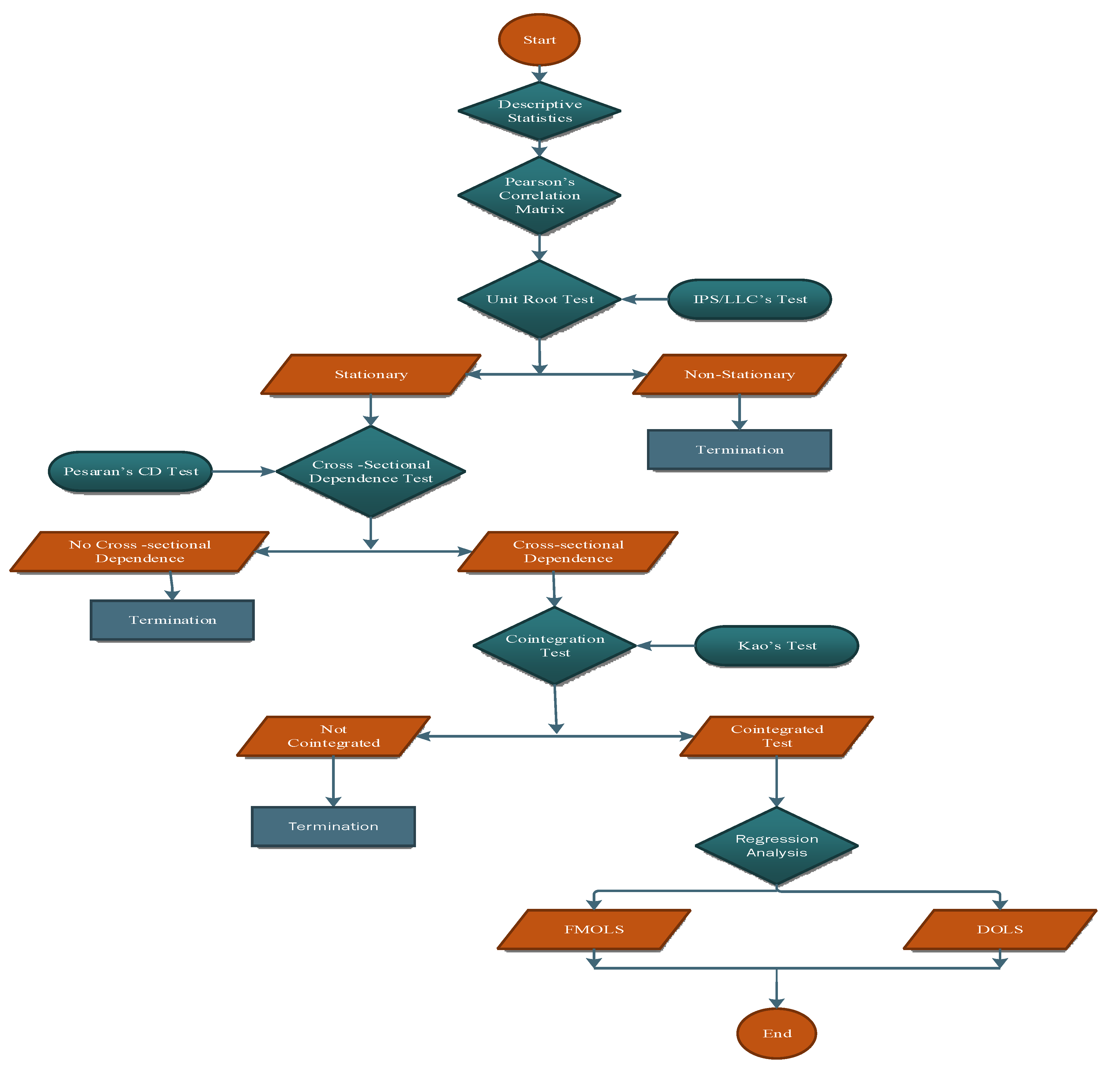

5.4. Econometric Modelling

5.4.1. Stationarity Test

5.4.2. Cross-Section Dependence

5.4.3. Cointegration Test

5.4.4. Estimation Strategy

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Premilinary Tests

6.2. Hypothesis Testing

6.2.1. Section 1: The Effect of Board Characteristics and Composite CSR

6.2.2. Section II: The Effect of Board Characteristics and the Three Components of CSR Performance

7. Conclusions, Policy Implications and Suggestions for Future Studies

- ■

- The findings of the panel FMOLS and DOLS estimators indicate a positive and statistically significant relationship between the board size and corporate sustainability reporting. Additionally, for the three dimensions of corporate sustainability reporting, the findings indicate that a larger board size increases economic, environmental, and social corporate sustainability reporting. This indicates that larger boards increase the likelihood of disclosing information regarding economic, environmental, and social sustainability.

- ■

- Additionally, we discovered a positive relationship between board independence and corporate sustainability reporting. Similar outcomes are observed for all three dimensions of corporate sustainability reporting. One explanation for the positive relationship is that Chinese companies have more external directors on their boards, who are more likely to promote reporting on social, economic, and environmental sustainability information.

- ■

- In the case of CEO duality, the result indicates a negative relationship with corporate sustainability reporting. The results for all three dimensions of corporate sustainability reporting are also negative. This suggests that when a CEO has more than one board position, the likelihood of reporting sustainable information about the company’s economic, environmental, and social performance decreases. Although only 13.9% of companies in our sample have the same person occupying the CEO and board’s chairmanship position, the trend towards CEO duality should not be countenanced.

- ■

- Board meeting characteristics also reveal a positive and significant relationship with corporate sustainability reporting and its three dimensions. Frequent board meetings increase the likelihood of reporting sustainable information about their economic, environmental, and social performances to stakeholders.

- ■

- Board committees also reveal a positive and significant relationship with corporate sustainability reporting and its three dimensions. This demonstrates that committees tasked with overseeing the operations of a company’s boards increase the likelihood of reporting information relating to economic, environmental, and social sustainability.

- ■

- In our sample, the board members ranged from three to twenty. A larger board size increases the likelihood of reporting on corporate sustainability reporting. Therefore, businesses are encouraged to consider expanding their boards to improve sustainability reporting. Nonetheless, future research on the optimal board size would be interesting.

- ■

- It is strongly suggested that the number of independent directors on boards be increased to guarantee effective advocacy for issues that are stakeholder-driven.

- ■

- The board chairmanship and the position of the chief executive officer should be separated. In other words, the positions should not be held by one person.

- ■

- The directors are also encouraged to attend all scheduled board meetings to enhance the board’s diligence in performing its duties.

- ■

- Moreover, boards should create committees to promote corporate sustainability. Therefore, the formation of board committees responsible for sustainability issues should be encouraged.

- ■

- As shown in the descriptive statistics, while some Chinese manufacturing industries have achieved very high CSR, economic, environmental, and social scores, exceeding 70%, others have achieved very low levels, falling below 5%. As a result, many low-scoring companies have much room to improve their CSR performance and impacts and their economic, environmental, and social performance. Companies with high scores should serve as benchmarks and invest in capacity building to improve their performance for the low-scoring companies.

- ■

- Finally, these industries are encouraged not to evaluate their sustainability practices isolated from their overall corporate strategy, because the sector is prone to predictable and unpredictable environmental and social challenges and operational risks that ensure the sustainable development of their industries.

- ■

- First, the study did not consider all board characteristics, but the variables used in this study covered most variables used in previous studies. Other board characteristics which could be considered in future research include board diversity, board experience, board ownership, and board compensation.

- ■

- Again, the sample size in this study was limited to listed companies on Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges. Future studies can be extended to non-listed companies and compare the two categories.

- ■

- Finally, the study used a GRI-based index. Future studies can also explore other indices like integrated reporting and triple-bottom approaches.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hussain, N.; Rigoni, U.; Orij, R.P. Corporate governance and sustainability performance: Analysis of triple bottom line per-formance. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Edziah, B.; Song, X.; Kporsu, A.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Estimating Persistent and Transient Energy Efficiency in Belt and Road Countries: A Stochastic Frontier Analysis. Energies 2020, 13, 3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Edziah, B.K.; Kporsu, A.K.; Sarkodie, S.A.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Energy efficiency: The role of technological inno-vation and knowledge spillover. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 167, 120659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edziah, B.K.; Sun, H.; Anyigbah, E.; Li, L. Human Capital and Energy Efficiency: Evidence from Developing Countries. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2021, 11, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, C. Corporate governance, social responsibility information disclosure, and enterprise value in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A. A decade of sustainability reporting: Developments and significance. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. 2004, 3, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoutsi, A.S.; ManMohan, S. Does disclosure in sustainability reports indicate actual sustainability performance? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A.; Muhtasim, D.A.; Farhana, S.; Pavel, M.I.; Faruk, O.; Rahman, M.; Mahmood, A. Nexus between carbon emissions, economic growth, renewable energy use, urbanization, industrialization, technological innovation, and forest area towards achieving environmental sustainability in Bangladesh. Energy Clim. Chang. 2022, 3, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, S.; Roper, I.; Muller-Camen, M.; Szigetvari, E. Have labour practices and human rights disclosures enhanced corporate accountability? The case of the GRI framework; Paper presented at the Accounting forum. In Accounting Forum; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N.; Aguilera-Caracuel, J.; Morales-Raya, M. Corporate governance and environmental sustainability: The moderating role of the national institutional context. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htay, S.N.N.; Rashid, H.M.A.; Adnan, M.A.; Meera, A.K.M. Impact of Corporate Governance on Social and Environmental Information Disclosure of Malaysian Listed Banks: Panel Data Analysis. Asian J. Finance Account. 2012, 4, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Loh, L. Board Governance and Sustainability Disclosure: A Cross-Sectional Study of Singapore-Listed Companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W.; de Sousa-Filho, J.M. Board structure and environmental, social, and governance disclosure in Latin America. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 102, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, F.; Razzaq, A.; Ming, J.; Razi, U. Firm characteristics, governance mechanisms, and ESG disclosure: How caring about sustainable concerns? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 82064–82077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, Z.; Kouser, R.; Ali, W.; Ahmad, Z.; Salman, T. Does Corporate Governance Affect Sustainability Disclosure? A Mixed Methods Study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.; Kaium, A.; Nurunnabi, M.; Bae, S.M. The effects of corporate governance on environmental sustainability reporting: Empirical evidence from South Asian countries. Asian J. Sustain. Soc. Responsib. 2018, 3, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naciti, V. Corporate governance and board of directors: The effect of a board composition on firm sustainability performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Karaman, A.S.; Kilic, M.; Uyar, A. Board attributes, CSR engagement, and corporate performance: What is the nexus in the energy sector? Energy Policy 2020, 143, 111582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jizi, M. The Influence of Board Composition on Sustainable Development Disclosure. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 26, 640–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behaviour, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G. A resource dependence perspective. In Intercorporate relations. In the Structural Analysis of Business; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Aliyu, U.S. Board characteristic and corporate environmental reporting in Nigeria. Asian J. Account. Res. 2019, 4, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrikat, J.; de Villiers, C.; Guenther, T.W.; Guenther, E.M. Board Characteristics and Corporate Social Responsibility: A Meta-Analytic Investigation. Bus. Soc. 2021, 60, 2099–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhu, Y. Linking governance structure and sustainable operations of Chinese manu-facturing firms: The moderating effect of internationalization. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbas, H.E. The relationship between board characteristics and environmental disclosure: Evidence from Turkish listed com-panies. South East Eur. J. Econ. Bus. 2016, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, M.; Yilmaz, M.K.; Tatoglu, E.; Basar, M. Antecedents of corporate sustainability performance in Turkey: The effects of ownership structure and board attributes on non-financial companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qunhui, H. The Centenary of the CPC: Socialist Industrial Development and Historical Experience. China Econ. 2021, 16, 26–41. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, R.; Zhang, X.; Bizimana, A.; Zhou, T.; Liu, J.-S.; Meng, X.-Z. Achieving China’s carbon neutrality: Predicting driving fac-tors of CO2 emission by artificial neural network. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W.; Higgins, C. Stakeholders’ Perspectives on the Role of Regulatory Reform in Integrated Reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, T.; Jamali, D. Looking Inside the Black Box: The Effect of Corporate Governance on Corporate Social Responsibility. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2016, 24, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.; Lu, Y.; Liang, Q. Corporate Social Responsibility in China: A Corporate Governance Approach. J. Bus. Ethic 2016, 136, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Abeysekera, I.; Cortese, C. Corporate social responsibility reporting quality, board characteristics and corporate social reputation: Evidence from China. Pac. Account. Rev. 2015, 27, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboud, A.; Diab, A. Ownership Characteristics and Financial Performance: Evidence from Chinese Split-Share Structure Reform. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, N.; Yaacob, M.; Jaffar, N. Governance structure, corporate restructuring and performance. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 15, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Buallay, A.; Hamdan, A.; Zureigat, Q. Corporate governance and firm performance: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2017, 11, 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyadh, H.A.; Sukoharsono, E.G.; Alfaiza, S.A. The impact of corporate social responsibility disclosure and board character-istics on corporate performance. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2019, 6, 1647917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazalin, N.; Mahmood, M. Economic, environmental, and social performance indicators of sustainability reporting: Evidence from the Russian oil and gas industry. Energy Policy 2018, 121, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Laine, M.; Roberts, R.W.; Rodrigue, M. Organized hypocrisy, organizational façades, and sustainability reporting. Account. Organ. Soc. 2015, 40, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienes, D.; Sassen, R.; Fischer, J. What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2016, 7, 154–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Ji, X. Economic growth quality, environmental sustainability, and social welfare in China-provincial assessment based on genuine progress indicator (GPI). Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haibo, C.; Ayamba, E.C.; Agyemang, A.O.; Afriyie, S.O.; Anaba, A.O. Economic development and environmental sustaina-bility—The case of foreign direct investment effect on environmental pollution in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 7228–7242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Sarkis, J.; Dou, Y. Corporate sustainability development in China: Review and analysis. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2015, 115, 5–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Hung, M.; Wang, Y. The effect of mandatory CSR disclosure on firm profitability and social externalities: Evidence from China. J. Account. Econ. 2018, 65, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Walker, M.; Zeng, C.C. Do Chinese state subsidies affect voluntary corporate social responsibility disclosure? J. Account. Public Policy 2017, 36, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Liang, T.; Ye, H. Occupational status, working conditions, and health: Evidence from the 2012 China Labor Force Dy-namics Survey. J. Chin. Sociol. 2020, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Lin, T.P.; Zhang, Y. Corporate Board and Corporate Social Responsibility Assurance: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seele, P. Digitally unified reporting: How XBRL-based real-time transparency helps in combining integrated sustainability re-porting and performance control. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, F.; Faria, L.G.D. Addressing the SDGs in sustainability reports: The relationship with institutional factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, A.A.; Schrack, D.; Greiling, D. Sustainability reporting and management control—A systematic exploratory literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 122725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortar, L. Materiality Matrixes in Sustainability Reporting: An Empirical Examination. SSRN 3117749. 2018. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3117749 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Shaw, H. The regulatory and legal framework of corporate governance. In A Handbook of Corporate Governance and Social Responsibility; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Jizi, M.I.; Salama, A.; Dixon, R.; Stratling, R. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from the US banking sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, M.; Lorsch, J.W. A modest proposal for improved corporate governance. Bus. Lawyer 1992, 48, 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. In Corporate Governance; Gower: London, UK, 2019; pp. 77–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Dou, J.; Jia, S. A meta-analytic review of corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance: The moderating effect of contextual factors. Bus. Soc. 2016, 55, 1083–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chams, N.; García-Blandón, J. Sustainable or not sustainable? The role of the board of directors. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, K.S.; Pesaran, M.; Shin, Y. Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J. Econ. 2003, 115, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.; Lin, C.-F.; Chu, C.-S.J. Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. J. Econ. 2002, 108, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. J. Appl. Econ. 2007, 22, 265–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C. Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. J. Econ. 1999, 90, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P. Fully modified OLS for heterogeneous cointegrated panels. In Nonstationary Panels, Panel Cointegration, and Dynamic Panels; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, J.H.; Watson, M.W. A simple estimator of cointegrating vectors in higher order integrated systems. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1993, 61, 783–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.C.; Moon, H.R. Linear regression limit theory for nonstationary panel data. Econometrica 1999, 67, 1057–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, M.; Elkadi, M. Estimating water treatment plants costs using factor analysis and artificial neural networks. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 4540–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. Time Series and Panel Data Econometrics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| S # | Dimension | Category | Aspect | Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Economic | Economic performance indicators | Economic performance, market presence, indirect economic impacts, and procurement practices. | 9 |

| 2 | Environmental | Environmental performance indicators | Materials, energy, water, biodiversity, emissions, effluents and waste, products and services, compliance, transport, overall, supplier environmental assessment, and environmental grievance mechanisms. | 28 |

| 3 | Social | Labour practice and decent work performance indicators | Employment Labour/Management relations Occupational health and safety training and education Diversity and equal opportunity Equal remuneration for women and men. | 15 |

| Human rights performance indicators | Investment and procurement practice Non-discrimination Freedom of association and collective bargaining Child labour, forced and compulsory labour, security practices, Indigenous rights, assessment, remediation | 11 | ||

| Social performance indicators | Local communities, corruption, public policy, anti-competitive behaviour, compliance | 10 | ||

| Product responsibility performance indicators | Customer health and safety Product and service labelling Marketing and communications Customer privacy Compliance | 9 | ||

| Total | 82 | |||

| Category | Sub-Category | Abrev | Description/Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Corporate sustainability reporting index | CSRI | The metric assigns “1” to each item in the sustainability report if the item is disclosed, and “0” for a non-disclosed item. |

| Economic sustainability reporting | ECON | All 9 items listed in the economic indicators are assigned “1” if the item is disclosed and “0” if it is non-disclosed. | |

| Environmental sustainability reporting | ENV | All 28 items listed in the environmental indicators are assigned “1” if the item is disclosed and “0” if it is non-disclosed. | |

| Social sustainability reporting | SOC | All 45 items listed in the environmental indicators are assigned “1” if the item is disclosed and “0” if it is non-disclosed. | |

| Independent Variables | Board size | BS | Total number of directors on the board |

| Board independence | BIND | The proportion of independent directors on the board | |

| CEO duality | CEO_Dual | Used a binary variable where “1” indicates whether the CEO serves as chairman, and “0” indicates otherwise. | |

| Board meeting | BOD_Mtg | Number of times meetings are held | |

| Board’s committees | BC | Number of committees on the board | |

| Control Variables | Return on assets | ROA | Net profit/total assets |

| Leverage | LEV. | Total liabilities are divided by the total assets | |

| Companies age | Fage | It is calculated as the number of years elapsed since its establishment | |

| Company size | Size | The log of the total assets at the end of the period | |

| BIG 4 | BIG4 | Reports of companies audited by any BIG 4 auditing companies are denoted as “1” and otherwise “0” |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 9842 | 63.035 | 48.273 | 0.215 | 79.132 | |

| Economic | 9842 | 24.304 | 42.894 | 0.275 | 76.437 | |

| Environmental | 9842 | 59.114 | 49.165 | 0.043 | 92.063 | |

| Social | 9842 | 60.770 | 48.829 | 0.422 | 92.480 | |

| Board Size | 9842 | 9.343 | 2.021 | 3 | 20 | 3.19 |

| Bind | 9842 | 3.387 | 0.749 | 1 | 8 | 3.21 |

| CEO Duality | 9842 | 0.139 | 0.346 | 0 | 1 | 1.03 |

| Board Mtg | 9842 | 9.413 | 4.223 | 2 | 56 | 1.06 |

| Board Cttee | 9842 | 3.856 | 0.729 | 0 | 8 | 1.07 |

| Company Size | 9842 | 9.589 | 0.637 | 7.26 | 13.45 | 1.62 |

| Lev | 9842 | 9.671 | 210.176 | 0 | 13,252.58 | 1.00 |

| ROA | 9842 | 0.107 | 2.293 | −19.55 | 187.47 | 1.01 |

| Company Age | 9842 | 19.486 | 5.301 | 2 | 41 | 1.33 |

| Big4 | 9842 | 0.088 | 0.283 | 0 | 1 | 1.18 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) CSR | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| (2) Economic | 0.434 * | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| (3) Environmental | 0.721 * | 0.436 * | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (4) Social | 0.753 * | 0.455 * | 0.872 * | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (5) Board Size | 0.028 * | 0.150 * | 0.038 * | 0.041 * | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (6) Bind | 0.064 * | 0.179 * | 0.075 * | 0.076 * | 0.822 * | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (7) CEO Duality | −0.009 | −0.037 * | −0.009 | −0.005 | −0.155 * | −0.115 * | 1.000 | |||||||

| (8) Board Mtg | 0.096 * | 0.081 * | 0.081 * | 0.098 * | 0.003 | 0.041 * | 0.006 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (9) Board Cttee | 0.142 * | 0.094 * | 0.136 * | 0.141 * | 0.092 * | 0.138 * | 0.002 | 0.085 * | 1.000 | |||||

| (10) Firm Size | 0.323 * | 0.376 * | 0.338 * | 0.328 * | 0.335 * | 0.363 * | −0.084 * | 0.214 * | 0.136 * | 1.000 | ||||

| (11) Lev | −0.009 | −0.017 | −0.014 | −0.007 | −0.010 | −0.013 | 0.019 | 0.002 | −0.011 | −0.038 * | 1.000 | |||

| (12) ROA | 0.024 * | 0.012 | 0.027 * | 0.025 * | 0.015 | 0.023 * | −0.009 | 0.019 | −0.003 | −0.040 * | −0.001 | 1.000 | ||

| (13) Firm Age | 0.478 * | 0.171 * | 0.450 * | 0.448 * | −0.076 * | −0.019 | 0.036 * | 0.084 * | 0.182 * | 0.180 * | 0.003 | 0.028 * | 1.000 | |

| (14) Big4 | 0.101 * | 0.172 * | 0.112 * | 0.103 * | 0.161 * | 0.162 * | −0.041 * | 0.062 * | −0.003 | 0.377 * | −0.003 | 0.044 * | 0.029 * | 1.000 |

| TEST | IPS | LLC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | 1st Difference | Level | 1st Difference | |

| CSR | 0.09534 | −14.6182 *** | −8.053 *** | −29.956 *** |

| Economical | −7.45071 *** | −19.6617 *** | −20.219 *** | −16.220 *** |

| Environmental | −1.56255 | −15.6631 *** | −10.951 *** | −26.581 *** |

| Social | 0.99421 | −12.0233 *** | −6.915 *** | −26.821 *** |

| Board Size | −10.8785 *** | −19.9493 *** | −53.763 *** | −29.002 *** |

| BIND | −2.36781 *** | −10.2294 *** | −16.434 *** | −19.804 *** |

| CEO Dual | −1.60287 | −8.31628 *** | −10.834 *** | −16.523 *** |

| Board Mtg | −13.8279 *** | −35.8510 *** | −29.021 *** | −49.589 *** |

| Board Cttee | −6.88683 *** | −17.6486 *** | −16.113 *** | −13.934 *** |

| ROA | 10.8823 | −7.47590 *** | 6.806 | −72.263 *** |

| Firm Size | 31.7197 | 12.8127 *** | 40.799 | −35.575 *** |

| Firm Age | 0.65544 | −0.27031 *** | 64.471 | −1.093 *** |

| LEV. | −13.6533 *** | −31.9785 *** | 18.086 | −98.557 *** |

| BIG4 | 1.34573 | −2.78607 *** | −3.676 *** | −8.366 *** |

| Variable | CD-Test | p-Value | Corr | Abs (Corr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 946.912 | 0.000 | 0.51 | 0.52 |

| Economic | 98.532 | 0.000 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| Environmental | 855.582 | 0.000 | 0.46 | 0.47 |

| Social | 864.17 | 0.000 | 0.46 | 0.48 |

| Board Size | 45.128 | 0.000 | 0.02 | 0.23 |

| BIND | 6.416 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.09 |

| CEO Dual | 2.31 | 0.021 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Board Mtg | 94.738 | 0.000 | 0.05 | 0.25 |

| Board Cttee | 100.084 | 0.000 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Firm Size | 654.22 | 0.000 | 0.35 | 0.53 |

| LEV | 8.559 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.21 |

| ROA | 174.588 | 0.000 | 0.09 | 0.34 |

| Firm Age | 1837.193 | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| BIG4 | 0.607 | 0.005 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| CSR | Economic CSR | Environmental CSR | Social CSR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | t-Statistic | Prob. | t-Statistic | Prob. | t-Statistic | Prob. | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| ADF | −20.1442 | 0.0000 | −25.6959 | 0.0000 | −19.926 | 0.0000 | −18.3040 | 0.0000 |

| Variables | Column (I) | Column (II) | Column (III) | Column (IV) | Column (V) | Column (VI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | |

| Board Size | 0.0052 *** | 0.00014 *** | 0.0030 *** | 0.0031 *** | ||||||||

| BIND | 0.0138 *** | 0.0060 *** | 0.0078 *** | 0.0131 *** | ||||||||

| CEO duality | −0.0328 *** | −0.0181 *** | −0.0293 *** | −0.018 *** | ||||||||

| Board Mtg | 0.0009 ** | 0.0003 ** | 0.00153 *** | 0.00027 *** | ||||||||

| Board C’ttee | 0.01658 *** | 0.01322 *** | 0.01882 *** | 0.0136 *** | ||||||||

| Firm Size | 0.1968 ** | 0.1402 ** | 0.1971 ** | 0.1411 ** | 0.19174 *** | 0.1405 *** | 0.1914 ** | 0.1398 *** | 0.1865 *** | 0.1387 *** | 0.1981 *** | 0.1392 *** |

| Leverage | −1.51 × 10−6 | −7.82 × 10−6 | −1.67 × 10−6 | −7.91 × 10−6 | −1.63 × 10−7 | −7.73 × 10−6 | −1.56 × 10−6 | −7.87 × 10−6 | −2.33 × 10−6 | −7.57 × 10−6 | −1.31 × 10−6 | −7.69 × 10−6 |

| ROA | 0.0057 ** | 0.0008 *** | 0.0057 ** | 0.00087 *** | 0.0055 ** | 0.00083 *** | 0.00553 ** | 0.00084 *** | 0.0055 ** | 0.0007 *** | 0.0059 *** | 0.0008 *** |

| Firm Age | 0.0257 *** | 0.605 *** | 0.0258 ** | 0.0681 *** | 0.0258 ** | 0.0682 *** | 0.0260 ** | 0.681 *** | 0.02564 ** | 0.67763 *** | 0.0253 *** | 0.0678 *** |

| BIG4 | −0.0111 | −0.8791 | −0.011980 | −0.0515 | −0.0113 | −0.0523 | −0.0117 | −0.0515 | −0.00593 | −0.0525 | −0.0063 | −0.0532 |

| Obs | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 |

| Constant | −1.6916 | −1.6965 | −1.6978 | −1.6831 | −1.7032 | −1.7545 | ||||||

| R Squared | 0.11441 | 0.5887 | 0.11492 | 0.5887 | 0.1131 | 0.5888 | 0.11363 | 0.5887 | 0.1171 | 0.5889 | 0.11778 | 0.589 |

| Variables | Column (I) | Column (II) | Column (III) | Column (IV) | Column (V) | Column (VI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | |

| Board Size | 0.0116 *** | 0.0018 *** | 0.00203 *** | 0.0061 *** | ||||||||

| BIND | 0.0402 *** | 0.0182 *** | 0.0417 *** | 0.0268 *** | ||||||||

| CEO Duality | −0.0103 *** | −0.0239 *** | −0.0034 *** | −0.0236 *** | ||||||||

| Board Mtg | 0.00207 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.001962 *** | 0.0010 *** | ||||||||

| Board C’ttee | 0.0265 *** | 0.0189 *** | 0.0219 *** | 0.0176 *** | ||||||||

| Firm Size | 0.2434 *** | 0.1015 *** | 0.2380 *** | 0.0997 *** | 0.2571 *** | 0.1023 *** | 0.261 *** | 0.100 *** | 0.2548 *** | 0.099 *** | 0.23976 *** | 0.0971 *** |

| Leverage | −0.00002 | −7.06 × 10−6 | −0.00002 | −6.79 × 10−6 | −0.00002 | −6.94 × 10−6 | −0.00002 | −7.21 × 10−6 | −0.00002 | −6.71 × 10−6 | −0.00002 | −6.37 × 10−6 |

| ROA | 0.00297 ** | 6.83 × 10−5 ** | 0.0027 *** | 0.00015 ** | 0.0033 ** | 9.14 × 10−5 ** | 0.00337 ** | 7.75 × 10−5 ** | 0.00335 ** | 0.00015 ** | 0.0028 ** | 0.0002 ** |

| Firm Age | 0.00896 *** | 0.0146 *** | 0.0088 *** | 0.0148 *** | 0.0085 *** | 0.0146 *** | 0.0086 *** | 0.0145 *** | 0.0081 *** | 0.0398 *** | 0.00848 *** | 0.0139 *** |

| BIG4 | −0.0205 | −0.0657 | −0.0217 | −0.0656 | −0.0224 | −0.0647 | −0.0217 | −0.0658 | −0.0256 | −0.0643 | −0.02405 | −0.0635 |

| Observations | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 |

| Constant | −2.4205 | −2.3946 | −2.4337 | −2.4512 | −2.5088 | −2.4566 | ||||||

| R Squared | 0.1469 | 0.5322 | 0.1480 | 0.5325 | 0.1455 | 0.5324 | 0.1449 | 0.5323 | 0.1425 | 0.5327 | 0.1447 | 0.5332 |

| Variables | Column (I) | Column (II) | Column (III) | Column (IV) | Column (V) | Column (VI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | |

| Board Size | 0.0053 *** | 0.00021 *** | 0.0061 *** | 0.0009 *** | ||||||||

| BIND | 0.0125 *** | 0.0020 *** | 0.0015 *** | 0.0059 *** | ||||||||

| CEO duality | −0.0020 *** | −0.0382 *** | −0.0021 *** | −0.0383 *** | ||||||||

| Board Mtg | 0.0033 *** | 0.0068 *** | 0.0039 *** | 0.0007 *** | ||||||||

| Board C’ttee | 0.1363 *** | 0.013 *** | 0.0177 *** | 0.0137 *** | ||||||||

| Firm Size | 0.2208 *** | 0.1421 *** | 0.2203 ** | 0.142 *** | 0.2139 *** | 0.1426 *** | 0.2186 *** | 0.1431 *** | 0.212 *** | 0.1405 *** | 0.2243 *** | 0.1424 *** |

| Leverage | 2.49 × 10−7 | −1.93 × 10−5 | −3.52 × 10−7 | −1.93 × 10−5 | −2.03 × 10−7 | −1.91 × 10−5 | −1.16 × 10−6 | −1.92 × 10−5 | −1.08 × 10−6 | −1.90 × 10−5 | −2.17 × 10−6 | −1.88 × 10−5 |

| ROA | 0.0080 *** | 0.0024 ** | 0.0080 ** | 0.0024 *** | 0.0075 *** | 0.00232 *** | 0.0079 *** | 0.0024 *** | 0.00787 *** | 0.0023 *** | 0.0083 * | 0.0023 *** |

| Firm Age | 0.0236 *** | 0.644 ** | 0.0237 ** | 0.0644 *** | 0.0239 *** | 0.0645 *** | 0.024 *** | 0.064 *** | 0.0235 *** | 0.064 *** | 0.0234 *** | 0.0642 *** |

| BIG4 | −0.0113 | −0.0195 | −0.0121 | −0.0195 | −0.01152 | −0.0210 | −0.0127 | −0.0196 | −0.0064 | 0.0639 | −0.0072 | −0.0221 |

| Obs | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 |

| Constant | −1.906 | −1.909 | −1.892 | −1.908 | −1.914 | −1.954 | ||||||

| R Squared | 0.136 | 0.571 | 0.1369 | 0.571 | 0.1349 | 0.571 | 0.1363 | 0.5711 | 0.1382 | 0.5712 | 0.140 | 0.572 |

| Variables | Column (I) | Column (II) | Column (III) | Column (IV) | Column (V) | Column (VI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | FMOLS | DOLS | |

| Board Size | 0.0032 *** | 0.00355 *** | 0.0011 *** | 0.0067 *** | ||||||||

| BIND | 0.009 *** | 0.0004 *** | 0.0075 *** | 0.014 *** | ||||||||

| CEO Duality | −0.030 *** | −0.026 *** | −0.029 *** | −0.0248 *** | ||||||||

| Board Mtg | 0.0006 *** | 0.0001 *** | 0.0011 *** | 4.31 × 10−5 *** | ||||||||

| Board C’ttee | 0.0189 *** | 0.0176 *** | 0.02033 ** | 0.018 *** | ||||||||

| Firm Size | 0.203 | 0.1581 | 0.2034 | 0.1591 | 0.2004 | 0.1594 | 0.1999 | 0.1589 | 0.1951 | 0.1569 | 0.2034 | 0.156 |

| Leverage | −7.79 × 10−6 | −3.31 × 10−6 | −7.94 × 10−6 | −3.29 × 10−6 | −6.59 × 10−6 | −3.43 × 10−6 | −7.69 × 10−6 | −3.27 × 10−6 | −8.66 × 10−6 | −3.62 × 10−6 | −7.33 × 10−6 | −3.57 × 10−6 |

| ROA | 0.0065 | 0.0015 | 0.0065 | 0.0016 | 0.0064 | 0.00153 | 0.0064 | 0.0016 | 0.0064 | 0.0015 | 0.0067 | 0.0015 |

| Firm Age | 0.025 | 0.0638 | 0.0249 | 0.0636 | 0.025 | 0.0637 | 0.0251 | 0.0636 | 0.025 | 0.0631 | 0.025 | 0.0634 |

| BIG4 | −0.0181 | −0.057 | −0.01867 | −0.059 | −0.0178 | −0.0596 | −0.0181 | −0.057 | −0.0116 | −0.0599 | −0.0126 | −0.061 |

| Obs | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 | 9842 |

| Constant | −1.771 | −1.775 | −1.780 | −1.766 | −1.792 | −1.834 | ||||||

| R Squared | 0.094 | 0.582 | 0.095 | 0.583 | 0.0919 | 0.583 | 0.0925 | 0.5824 | 0.0969 | 0.583 | 0.099 | 0.583 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anyigbah, E.; Kong, Y.; Edziah, B.K.; Ahoto, A.T.; Ahiaku, W.S. Board Characteristics and Corporate Sustainability Reporting: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043553

Anyigbah E, Kong Y, Edziah BK, Ahoto AT, Ahiaku WS. Board Characteristics and Corporate Sustainability Reporting: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043553

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnyigbah, Emmanuel, Yusheng Kong, Bless Kofi Edziah, Ahotovi Thomas Ahoto, and Wilhelmina Seyome Ahiaku. 2023. "Board Characteristics and Corporate Sustainability Reporting: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043553

APA StyleAnyigbah, E., Kong, Y., Edziah, B. K., Ahoto, A. T., & Ahiaku, W. S. (2023). Board Characteristics and Corporate Sustainability Reporting: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability, 15(4), 3553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043553