Strategic Human Resources Management for Creating Shared Value in Social Business Organizations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

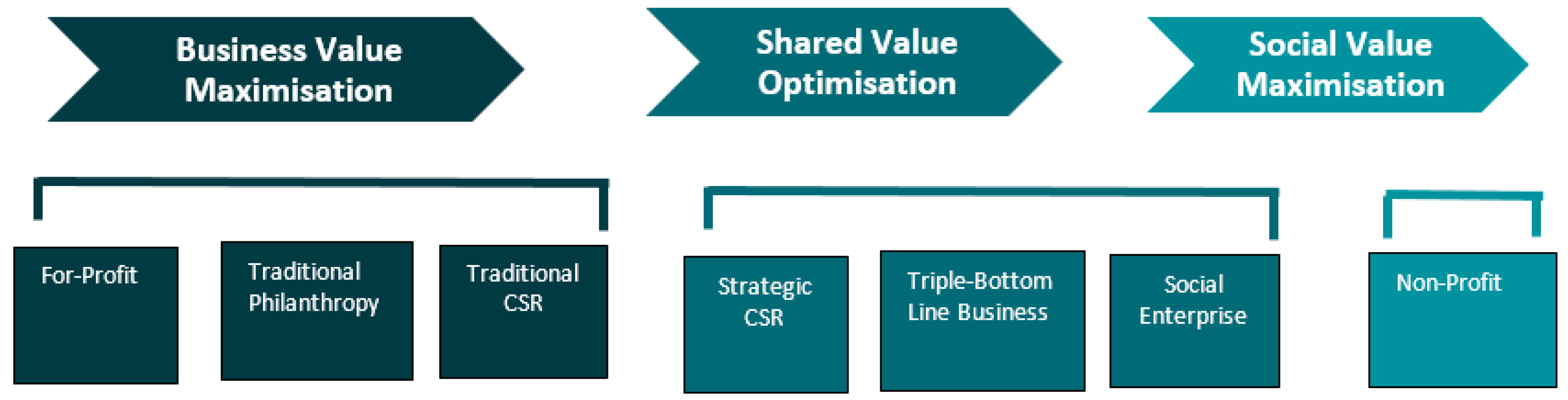

2. Theory and Framework

2.1. Social Business and CSV

2.2. Strategic Human Resource Management and Social Business Paradox

“It is a great challenge for us to increase tuition fees because we are facilitating impoverished students. However, to break even, we must increase tuition fees”.

“Traditional business is stringent in managing repayments, but being a social business, we cannot follow such strictness. We cannot pressure our clients to make repayments; that is one of our challenges”.

“We also increased the variety of our products, which now range in price from cheap to high. Before this, we relied on subsidy funds. However, this approach ensured sustainability. Before, we charged patients only 100 BDT, but we had to rely on subsidies. But now, by developing dynamic products and services, we have boosted our revenue. However, for those who can no longer afford healthcare services, we have a provision to provide them with free care. For them, we have established a separate fund known as the Surgery Support Fund, which is typically derived from the donations of others, CSR funds, or Zakat funds (donations made following Islamic law). You can also refer to this fund as a sponsored fund, as wealthy individuals sometimes sponsor some patients”.

“The only problem is that if, for example, someone thinks that working in a social business will help them make more money than working in a traditional business, they might be disappointed. Many people think this way. But we usually take on the market rate or even more than that, depending on our location. For example, finding the right person is hard if someone needs to work in a remote area. If a male or female with a master’s degree is asked to go to a village and do some work, it’s hard to find the right person. Even if we find the right person, the decision doesn’t last long”.

“Efficient people may not be willing to work in the field level. Those who want to work in the field level may not have adequate expertise in that field”.

“…if we charge different prices to different people, it becomes a talking point, especially in villages, so prices need to be the same…However, we can’t do that because one stakeholder is poor and the other is wealthy…”

“Since people from villages and peri-urban areas don’t want to come to Dhaka for treatment, we have built our hospital in villages. Here we are different from a traditional for-profit business. Because building a hospital in Dhaka could provide more opportunities for making a profit. But if we establish our hospital in Dhaka, then marginal people in villages will be deprived of healthcare services. Coming to Dhaka for treatment will put them in a financial mess”.

“My project, for instance, consists of rural and urban parts. My primary focus is on the rural option, whereas the urban option is more of a peripheral consideration. Thus, if I focus on the city, I can rapidly reach the break-even point of my business. And if I ignore the urban part and focus exclusively on the rural part, break-even will be reached a little later. We brought in the related activity to ease things”.

3. Study Profiles

3.1. Grameen Veolia Water Ltd. (GVW)

3.2. Grameen Caledonian College of Nursing (GCCN)

3.3. Grameen Telecom Trust (GTT)

3.4. Grameen Health Care Service (GHS)

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design and Sample

4.2. Data Collection and Analysis

5. Empirical Findings

5.1. Recruitment and Selection Strategies

“We try to extract the candidate’s commitment and adaptability regarding our social business principles but do not see it as a challenge or Tension”.

“during recruitment, we asked the candidates several questions to know their interest in social mission…We follow a formal recruitment procedure where representatives from the University of Dhaka, medical faculties, and nursing councils are required along with our internal recruitment team”.

5.2. Training and Development Strategies

“We have created good relations with some other hospitals and health professionals (like CITC and Ispahani) and urged them to provide doctors willing to work in districts rather than Dhaka. Collaboration with Sheba Foundation, Aravind Eye Hospital, etc., creates an opportunity to improve our workforce. Grameen Shikkha also helps us pay medical scholarships”.

“We look for the right skill sets for the right people in recruiting other staff. For our paramedics who have an HSC degree but not a nursing degree, we send them to Aravind Eye Hospital in India for two years of training. So, we made sure that our paramedics had the right skills”.

“After recruitment, we have one month training program. Employees first go through a one-week training program in the head office, and then they go for doing field work. To do their jobs effectively, our staff must be familiar with the local culture, the environment, livestock, and community management. Throughout the training, we try to develop their mind set which will be socially focused”.

5.3. Performance Evaluation Strategies

“We have our Performance Development Review (PDR) form to evaluate employees’ performance. Usually, in December or November, we do PDR review. Then what we do is, according to their job nature, we set a goal for each of the staff. The goal is like, there are social and business goals, and they need to fulfill the goal in a year”.

…“And in June, we conduct mid-term PDR, which determines how much they could achieve and whether they need any improvement. Based on PDR, we ensure their increment, promotion, etc. This PDR is from our side. We have another evaluation from the student side also”.

“We have a standard performance evaluation system that measures employee performance through KPI. For example, we measure customer satisfaction for those who are in customer service. For doctors, we measure the number of patients he has served or the number of operations he has made. Thus, we measure the performance of our nurses, paramedics, and doctors based on KPI. In KPI, some indicators are based on performance, and some are ethics and value-based….To measure value, we look at the urgency of work. For example, some employees sacrifice their leave during an emergency. We take note of those services. For each employee, we have a personal journal book where their yearly scores are recorded”.

“Every employee must have business efficiency, capability, and knowledge. Every employee must be aware of improving personal efficiency and organizational effectiveness. If they can do both, they get promotions and raises. If a person can balance professional and organizational goals, he enjoys career advancement”.

“Employees also reflect on self-performance on a given KPIs, followed by assessment by supervisors and line managers. The managing director finally evaluates the assessments for extracting the final employees’ scores”.

5.4. Compensation and Reward Strategies

“Not all of the employees understand social business. They think that it is a business-oriented platform. We need to make them understand what social business is. There are always some employees who often ask for increments and other facilities. Then we need to make them understand every time that this is not like the other companies; this is social business. We need to take care of both of our goals”.

“A ‘fixed number of students’ law’ and ‘social mission to keep minimum price’ prevent the institution from raising profit and employee salaries. Then we need to motivate our employees on our social purpose. Being a social business, we need to reach break-even which is important for our sustainability”.

5.5. Industrial Relations and Human Resource Retention Strategies

“Employees like to work in this organization due to having a very good working environment….democratic environment exist in our organization as we take all the decisions in consultation with all the staffs. Because we accept input from employees. Therefore, we experience very few turnovers”.

“we provide scholarship to our students to pursue higher studies in UK with a provision to come back and join as faculty members of our college at least for 5 years. Four faculties have already joined in that way. In this way we not only developing our employees, we are also getting committed employees for our nursing college. Moreover, most of our students came from Grameen Bank borrowers’ family. When they join as employees they remain grateful and committed to our college”.

“since many of our employees self-select themselves for serving social business organization, they remain committed to our social goals. Moreover, those who are not willing to work in remote areas we usually do not hire them. Thus retention of our employees is not a major concern for us”.

“We emphasize work environment and industrial relations. We provide good logistics. We’re also building a gym and meditation center for our employees. We focus on excellent salaries and a comfortable working atmosphere because they work 8 h a day. We provide motivation training to boost their service dedication”.

6. Discussion

7. Limitation and Future Research

8. Conclusions

9. Managerial Implication

10. Social Implication

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wright, P.M.; Dunford, B.B.; Snell, S.A. Human resources and the resource based view of the firm. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lado, A.A.; Wilson, M.C. Human resource systems and sustained competitive advantage: A competency-based perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 699–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowhan, J.; Pries, F.; Mann, S. Persistent innovation and the role of human resource management practices, work organization, and strategy. J. Manag. Organ. 2017, 23, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scarbrough, H. Knowledge management, HRM and the innovation process. Int. J. Manpow. 2003, 24, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Cabrales, A.; Pérez-Luño, A.; Cabrera, R.V. Knowledge as a mediator between HRM practices and innovative activity. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Huang, J.-W. Strategic human resource practices and innovation performance—The mediating role of knowledge management capacity. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajogo, D.I.; Oke, A. Human capital, service innovation advantage, and business performance: The moderating roles of dynamic and competitive environments. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2016, 36, 974–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, R.S.; Jackson, S.E. Organizational strategy and organization level as determinants of human resource management practices. People Strategy 1987, 10, 125. [Google Scholar]

- Terpstra, D.E.; Rozell, E.J. The relationship of staffing practices to organizational level measures of performance. Pers. Psychol. 1993, 46, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martell, K.; Carroll, S.J. How strategic is HRM? Hum. Resour. Manag. 1995, 34, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Gonin, M.; Besharov, M.L. Managing social-business tensions: A review and research agenda for social enterprise. Bus. Ethics Q. 2013, 23, 407–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tracey, P.; Jarvis, O. Toward a theory of social venture franchising. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Leonard, H.; Epstein, M. Digital divide data: A social enterprise in action. Harv. Bus. Sch. Case Study 2007, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, D.B. Symposium: Human resource management in nonprofit organizations. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2003, 23, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohana, M.; Meyer, M. Should I stay or should I go now? Investigating the intention to quit of the permanent staff in social enterprises. Eur. Manag. J. 2010, 28, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvis, P.H. The quality of employment in the nonprofit sector: An update on employee attitudes in nonprofits versus business and government. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 1992, 3, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvis, P.H.; Hackett, E.J. Work and work force characteristics in the nonprofit sector. Mon. Labor Rev. 1983, 106, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dembek, K.; Singh, P.; Bhakoo, V. Literature review of shared value: A theoretical concept or a management buzzword? J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 231–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinthupundaja, J.; Kohda, Y.; Chiadamrong, N. Examining capabilities of social entrepreneurship for shared value creation. J. Soc. Entrep. 2020, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napathorn, C. Which HR bundles are utilized in social enterprises? The case of social enterprises in Thailand. J. Soc. Entrep. 2018, 9, 110–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegner, M.; Pinkse, J.; Panwar, R. Managing tensions in a social enterprise: The complex balancing act to deliver a multi-faceted but coherent social mission. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1314–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Mayson, S.; Teicher, J.; Barrett, R. Recruiting, managing and rewarding workers in social enterprises. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 2851–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, N.; Khosravi, E.; Azadi, H.; Karamian, F.; Viira, A.-H.; Nadiri, H. Barriers to developing social entrepreneurship in NGOs: Application of grounded theory in western Iran. J. Soc. Entrep. 2022, 13, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebi, T.; Foss, N.J.; Linder, S. Social entrepreneurship research: Past achievements and future promises. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.W. Exploring paradox: Toward a more comprehensive guide. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketkar, S.; Puri, R. Investigating the ‘mission and profit’ paradox: Case study of an ecopreneurial organisation in India. J. Soc. Entrep. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieth, P.; Schneider, S.; Clauß, T.; Eichenberg, D. Value drivers of social businesses: A business model perspective. Long Range Plann. 2019, 52, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdousi, F.; Mahmud, P.; Mahmud, K.T. Fostering youth entrepreneurship development through social business—Evidence from Bangladesh. Sustainability 2022, 15, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Martí, A.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; Palacios-Marqués, D. A bibliometric analysis of social entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1651–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M. Creating a World without Poverty; Commonwealth Club: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdousi, F.; Mahmud, P. Role of social business in women entrepreneurship development in Bangladesh: Perspectives from Nobin Udyokta projects of grameen telecom trust. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdousi, F.; Mahmud, P. Strategies for scaling up social business impact on sustainable living: A case study on SBLIF. Int. J. Manag. Innov. Entrep. Res. 2020, 6, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cato, S.; Nakamura, H. Understanding the function of a social business ecosystem. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M. Samajik Byabosha; Anonnya: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and Society: The Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 1 December 2006. Available online: https://hbr.org/2006/12/strategy-and-society-the-link-between-competitive-advantage-and-corporate-social-responsibility(accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value: How to Reinvent Capitalism and Unleash a Wave of Innovation and Growth. Harvard Business Review, 1 January 2011. Available online: https://hbr.org/2011/01/the-big-idea-creating-shared-value(accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Kendrick, A.; Fullerton, J.A.; Kim, Y.J. Social responsibility in advertising: A marketing communications student perspective. J. Mark. Educ. 2013, 35, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, C.L.Z.; Dubois, D.A. Expanding the vision of industrial–Organizational psychology contributions to environmental sustainability. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 480–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. A Response to Andrew Crane et al.’s Article by Michael E. Porter and Mark R. Kramer. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 149–151. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M. Capabilities for creating shared value: Optimizing social-business balance in Southeast and South Asian Countries. Annu. Status Rep. Emerg. Mark. Sustain. Status Issues 2020, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Kennelly, J.J. Sustainability and place-based enterprise. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakhus, M.; Bzdak, M. Revisiting the role of “shared value” in the business-society relationship. Bus. Prof. Ethics J. 2012, 31, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Palazzo, G.; Spence, L.J.; Matten, D. Contesting the value of “creating shared value”. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 130–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Dorado, S. Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1419–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jay, J. Navigating paradox as a mechanism of change and innovation in hybrid organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, W.K.; Besharov, M.L.; Wessels, A.K.; Chertok, M. A paradoxical leadership model for social entrepreneurs: Challenges, leadership skills, and pedagogical tools for managing social and commercial demands. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2012, 11, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Yuthas, K. Mission impossible: Diffusion and drift in the microfinance industry. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2010, 1, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Mayer, J.; Lutz, E. Navigating institutional plurality: Organizational governance in hybrid organizations. Organ. Stud. 2015, 36, 713–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Battilana, J.; Sengul, M.; Pache, A.-C.; Model, J. Harnessing productive tensions in hybrid organizations: The case of work integration social enterprises. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1658–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda: Social enterprises as hybrid organizations. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aust, I.; Brandl, J.; Keegan, A. State-of-the-art and future directions for HRM from a Paradox perspective: Introduction to the special issue. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 29, 194–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriopoulos, C.; Lewis, M.W. Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jarzabkowski, P.; Lê, J.K.; Van de Ven, A.H. Responding to competing strategic demands: How organizing, belonging, and performing paradoxes coevolve. Strateg. Organ. 2013, 11, 245–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, W.K.; Lewis, M.W. Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 381–403. [Google Scholar]

- Lepak, D.P.; Snell, S.A. The human resource architecture: Toward a theory of human capital allocation and development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDuffie, J.P. Human resource bundles and manufacturing performance: Organizational logic and flexible production systems in the world auto industry. Ilr Rev. 1995, 48, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.B. Effects of human resource systems on manufacturing performance and turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 670–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huselid, M.A. The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 635–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.R.; Davis, W.D. High-performance work systems and organizational performance: The mediating role of internal social structure. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 758–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Youndt, M.A.; Snell, S.A.; Dean, J.W., Jr.; Lepak, D.P. Human resource management, manufacturing strategy, and firm performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 836–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, R.; Banerjee, M. The scope and trajectory of strategic HR research: Evidence from American and British journals. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 1739–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, J.; Liu, Y.; Hall, A.; Ketchen, D. How much do high-performance work practices matter? A meta-analysis of their effects on organizational performance. Pers. Psychol. 2006, 59, 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Takeuchi, R.; Lepak, D.P. Where do we go from here? New perspectives on the black box in strategic human resource management research. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 50, 1448–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.B. The link between business strategy and industrial relations systems in american steel minimills. ILR Rev. 1992, 45, 488–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, L.L.; Fairhurst, G.T.; Banghart, S. Contradictions, dialectics, and paradoxes in organizations: A constitutive approach. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 10, 65–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I. Paradox as a lens for theorizing sustainable HRM. In Sustainability and Human Resource Management: Developing Sustainable Business Organizations; Ehnert, I., Harry, W., Zink, K.J., Eds.; CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 247–271. ISBN 978-3-642-37524-8. [Google Scholar]

- Belte, A. New avenues for hrm roles: A systematic literature review on HRM in hybrid organizations. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Z. Für Pers. 2022, 36, 148–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, D.; Dulebohn, J.H. Are we there yet? What’s next for HR? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2015, 25, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.; Moingeon, B.; Lehmann-Ortega, L. Building social business models: Lessons from the grameen experience. Long Range Plann. 2010, 43, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, G. The Prospects for Social Business in Peri-Urban Water Supply: Employment and Household Welfare Impacts of the Grameen Veolia Venture; Institute for Research on Labor & Employment: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, C.; Donaldson, C.; Anderson, M. Grameen caledonian partnership-How a university can help spread and develop a new approach to society’s ills. Soc. Bus. 2011, 1, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, B.; Nahar, N.S. Nursing education in Bangladesh: A social business model. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2016, 63, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.A.; Khan, G.M.; Taghizadeh, S.K. Creating new generation entrepreneurs (Nobin Uddyokta) at the rural areas: A social business model for sustainable development. In ICSB World Conference Proceedings; International Council for Small Business (ICSB): Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Grameen Telecom Trust. Available online: http://gtctrust.com/ (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Khakon, M.S.U. Grameen Health Care Service Homepage. Available online: https://www.grameenhealthcareservices.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=92&Itemid=105 (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Grameen Health Care Services Ltd. Available online: https://socialbusinesspedia.com/organizations/grameen-health-care-services-ltd/organization-contents/view/107 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Humberg, K.; Braun, B. Social business and poverty alleviation: Lessons from grameen danone and grameen veolia. In Social Business; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 201–223. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Luketić, D. Researc Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aberdeen, T.; Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Peerally, J.A.; Figueiredo, P.N. Techological Capability Building in MNE-Related Social Businesses of Less Developed Countries: The Experience of Grameen-Danone Foods in Bangladesh; UNU-MERIT: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P.M.; McMahan, G.C. Theoretical perspectives for strategic human resource management. J. Manag. 1992, 18, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, A.A.; Almazari, A.A. The impact of affective human resources management practices on the financial performance of the Saudi banks. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2014, 3, 327. [Google Scholar]

- Chompukum, P. Performance management effectiveness in Thai banking industry: A look from performers and a role of interactional justice. J. Int. Bus. Cult. Stud. 2012, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Delery, J.E.; Doty, D.H. Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 802–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N. Effect of direct participation on perceived organizational performance: A case study of banking sector of Pakistan. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 6, 220–230. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, W.K.L.; Hia, H.S. The effects of interactive leadership on human resource management in Singapore’s banking industry. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1997, 8, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quresh, T.M.; Akbar, A.; Khan, M.A.; Sheikh, R.A.; Hijazi, T. Do human resource management practices have an impact on financial performance of banks? Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Jelena, V.-D.; Jotic, J.; Maric, R.M. A comparative analysis of contribution of human resource management to organizational performance of banks in Serbia. Industrija 2013, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zorlu, K. Effect of human capital elements on organizational commitment in businesses and a study in the banking sector in Kırşehir province. Z. Welt Türken J. World Turks 2010, 2, 107–130. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, R.S.; Jackson, S.E. Linking competitive strategies with human resource management practices. Oxf. UK Blackwell 1999, 1, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyer, M.W.; Gupta, V. The performance paradox. Res. Organ. Behav. 1994, 16, 309–369. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, C.; Boselie, J.P.; Dietz, G. Commonalities and contradictions in research on human resource management and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 15, 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, J.M.; Ventura, J. Human resource management systems and organizational performance: An analysis of the spanish manufacturing industry. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2003, 14, 1206–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A.V.; Clegg, S.R.; Freeder, D. Compassion, power and organization. J. Polit. Power 2013, 6, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stone, D.L.; Dulebohn, J.H. Emerging issues in theory and research on electronic human resource management (EHRM). Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2013, 23, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Emergence of Social Enterprise-1st Edition-Carlo Borzaga-Ja. Available online: https://www.routledge.com/The-Emergence-of-Social-Enterprise/Borzaga-Defourny/p/book/9780415339216 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Magrizos, S.; Roumpi, D. Doing the right thing or doing things right? The role of ethics of care and ethics of justice in human resource management of social enterprises. Strateg. Chang. 2020, 29, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Morley, A. Eight paradoxes of the social enterprise research agenda. Soc. Enterp. J. 2008, 4, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royce, M. Using human resource management tools to support social enterprise: Emerging themes from the sector. Soc. Enterp. J. 2007, 3, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Lee, M. Advancing research on hybrid organizing–Insights from the study of social enterprises. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 397–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei-Skillern, J. Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Rev. Adm. 2012, 47, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grameen Veolia Water Ltd. | Grameen Caledonian College of Nursing | Grameen Health Car Service | Grameen Telecom Trust | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature of business | Joint venture | Joint venture | Company | Trust |

| Problem addressed | Arsenic-contaminated water in rural areas | Shortages of nurses, inaccessibility to medical care in poor rural communities | Blindness and eye diseases in undeserved rural Bangladeshis | Poverty and lack of employment opportunities among youth |

| Solution offered | Clean water through village taps points | Nursing education for underprivileged girls | Bringing healthcare facilities closer to rural population | Creating micro-entrepreneurs through Yunus social business fund |

| No. of employees | 16 | 62 | 307 | 200+ |

| Founding year | 2008 | 2010 | 2006 | 2010 |

| Collaboration | Grameen Health Care Service and Veolia Water (France) | Glasgow Caledonian University (UK) and Grameen Health Care Trust | SEVA (US), Orbis International (US), Arvind Eye Hospital and Graduate Institute of Ophthalmology (India), Green Children Foundation (Norway), Glasgow Caledonian University (UK), Veolia Water (France), Nike Foundation (US), Social Business Earth (Switzerland), Lavelle Foundation (US), and Calvert Foundation (US) | Grameen Danone Foods |

| Impact created | 8000 people have access to safe drinking water through 150 water connections, including three schools and 56 tap points | Nearly 600 hundred students became qualified nurses from the GCCN, they provide healthcare in both private and public sectors, and 500 students are studying in GCCN to become nurses | Treated 1.8 million patients, performed more than 1 (one) lac cataract surgeries and more than 94,000 other eye surgeries; provided free treatment to 4.78 lac patients and performed 8500 free surgeries. | Created more than 21,411 young micro-entrepreneurs from 2013 to 2019 in 17 districts of Bangladesh, constructed infrastructures for the social business ecosystem |

| Data Collection | Number | Rational |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-structured interviews with the Head of the companies (session length: 60–80 min) | 4 | To learn about the company’s background, operational path, and leadership and HRM challenges when meeting social and profit goals. |

| Semi-structured interviews with the team members, including follow-up interviews (session length: 60–90 min) | 4 | To learn about the organization’s operations, including project selection, culture, and team members’ challenges. |

| Participation in the internal review meeting, annual assessment, training, design labs and conferences | 8 | To assess how team members evaluate projects and allocate funds to entrepreneurial projects. |

| Archival data (videos and documents submitted for awards) | 10 | To obtain additional information on the background of social business companies, their projects, their focus areas and how these are communicated to external stockholders. |

| Site visits | 4 | To observe the operations and examine how the social business management teams work and interact with their employees. |

| Semi-structured interviews with the team customers (session length: 30–45 min) | 6 | To understand the customer’s experience of satisfaction with the social mission of social business companies. |

| GVW | GCCN | GHS | GTT |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HRM Strategies | GVW | GCCN | GHS | GTT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staffing | Retaining employees for the remote areas. | Retaining employees with a social mission. | Retaining physicians for rural services. | Retaining employees with a social mission. |

| Training | Not challenging. | Few difficulties in instilling a sense of social mission. | Higher training costs. | Not challenging. |

| Performance appraisal | Not challenging. | Not challenging. | Not challenging. | Not challenging. |

| Compensation and reward | Meeting employees’ high salary expectation. | Meeting employees’ high salary expectation. | Hiring qualified doctors and staff at reasonable salaries. Because medical fees are lower. | Balancing operational cost is difficult due to strict compliance on multiple business issues. |

| Industrial relations | Not challenging. | Not challenging. | Not challenging. | Not challenging. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferdousi, F.; Abedin, N. Strategic Human Resources Management for Creating Shared Value in Social Business Organizations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043703

Ferdousi F, Abedin N. Strategic Human Resources Management for Creating Shared Value in Social Business Organizations. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043703

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerdousi, Farhana, and Nuren Abedin. 2023. "Strategic Human Resources Management for Creating Shared Value in Social Business Organizations" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043703

APA StyleFerdousi, F., & Abedin, N. (2023). Strategic Human Resources Management for Creating Shared Value in Social Business Organizations. Sustainability, 15(4), 3703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043703