Assessing Tertiary Turkish EFL Learners’ Pragmatic Competence Regarding Speech Acts and Conversational Implicatures

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Is there a difference between the test results of the EFL learners’ production of speech acts and comprehension of implicature?

- Does the comprehension of implicature differ in terms of the participants’ proficiency levels?

- Does the performance of speech acts vary according to students’ levels of English proficiency?

- Is there a difference between the female and male participants’ pragmatic competence?

2. Background of the Study

2.1. The Importance of Instruments to Test Pragmatic Competence

2.2. Language Proficiency and Pragmatic Competence

2.3. Gender and Pragmatic Competence

2.4. Implicature

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

Pilot Study

- To provide the feasibility of the DCT.

- To observe how long it took the participants to complete the DCT and to see if the test is convenient.

- To establish whether the provided instructions and content of the circumstances in the DCT were coherent, comprehensible and not vague to bewilder EFL undergraduate participants.

- To detect whether the situations of the discourse completion task, such as pope questions, indirect criticism, (verbal) irony, indirect refusals, topic change disclosures, indirect requests (requestive hints), indirect advice and fillers, were recognizable to the participants [78].

3.2. Instruments

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

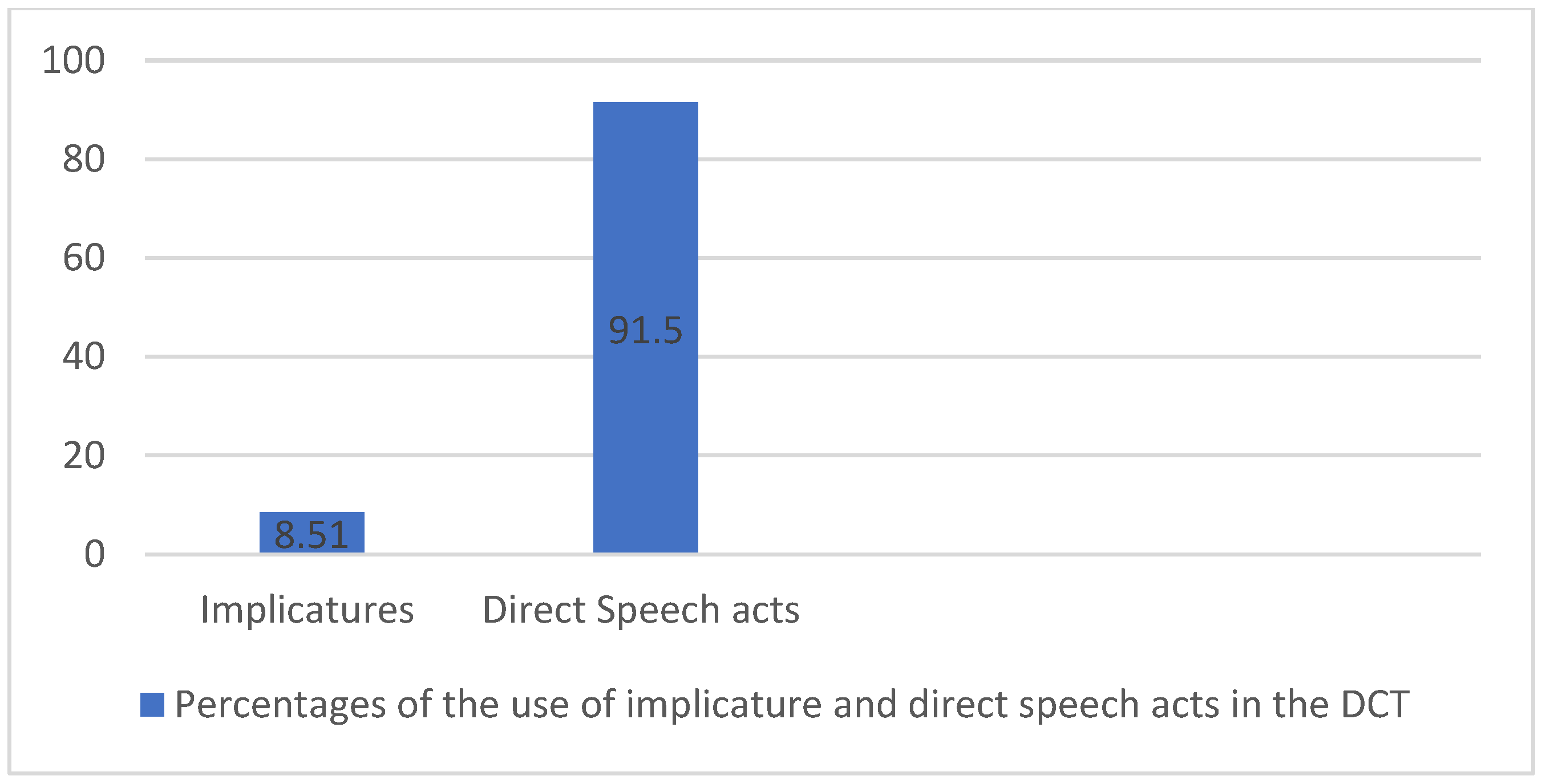

4.1. The Assessment of the Realization of Speech Acts and the Comprehension of Implicatures

4.2. Assessing EFL Participants’ Performances in the Comprehension of Implicature According to Their Level

4.3. Assessing Participants’ Production of Speech Acts According to Their Level of Proficiency

4.4. Assessing Gender Performances through the MCDT and DCT

5. Discussion

6. Conclusive Remarks

6.1. Summary

6.2. Pedagogical Implications

6.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- SECTION I: PERSONAL INFORMATION

- Please complete by ticking or crossing the boxes.

- SEX:

- Male:☐ Female:☐

- 2.

- AGE:

- 18–21:☐ 22–30:☐ 31–40:☐ 41–50:☐ 51 and over:☐

- 3.

- NATIONALTY: _____________

- 4.

- Stage:

- Preparatory school:☐ First year:☐ Second year:☐ Third year:☐ Fourth year:☐

- 5.

- LEVEL OF ENGLISH: _____________

- 6.

- How long have you been studying English for? ________________

- 7.

- I like learning English.

- (a)

- Strongly agree ☐

- (b)

- Agree ☐

- (c)

- Neutral ☐

- (d)

- Disagree ☐

- (e)

- Strongly disagree ☐

- SECTION II: PRODUCTION

- Please read carefully and answer the situations according to what you will do in each situation.

- Imagine you have a meeting to attend to and your colleague keeps asking you what day and time the meeting is. This is the fourth time he has asked you.

- Friend: Hmm, are you sure the meeting is on Monday at 4 p.m.?

- You: ______________________________________________________________.

- What do you say to your friend to say that it is clear/obvious that his answer is correct? Write it in the blank. Answer with a question.

- 2.

- Imagine your friend is going away for the weekend. She’s asked you to look after her cat. You love animals and you have no plans for the weekend, so it won’t be a problem for you.

- Friend: Thank you so much once again! It won’t cause you any trouble, will it?

- You: ______________________________________________________________.

- What do you say to your friend to show her that it won’t be a problem for you? Write it in the blank. Answer with a question.

- 3.

- Imagine that your sister is getting married. You are at a shop looking at wedding dresses. She tries on the dress and walks out. You can see that the dress doesn’t suit her at all. It is too short to be a wedding dress and it looks old-fashioned. She asks you for your opinion.

- Sister: So, what do you think? Do you like it?

- You: _____________________________________________________________.

- What do you say to your sister to show that you don’t like the wedding dress she has tried on? Write it in the blank.

- 4.

- Imagine you that you have gone to another country to study. You don’t like the place as it is so boring and nothing to do. Your cousin calls you from Turkey.

- Cousin: I heard it is paradise over there, is that right? How are you finding it there? Do you like it? Do you think I should come and study there too?

- You: _________________________________________________________________.

- How do you respond to your cousin? What do you say to show him/her that he/she shouldn’t come and that you don’t like living there? Write it in the blank.

- 5.

- Mark and Tom are colleagues. Mark always has problems writing emails to his boss and he always asks Tom what to write them. Tom doesn’t want to help. Imagine you are Mark and Tom hasn’t helped you. What do you say to Tom? Write it in the blank.

- Mark: Hey man! Couldyou help me with this email around lunchtime?

- Tom: Well, not this time, man. I’m sorry, bro. I have something to do.

- Mark: _______________________________________________________.

- 6.

- Susan is a very difficult person to get on with. She argues with nearly everyone she meets and doesn’t have many friends. You don’t like Susan either. A friend is interested in taking her out for a date and he asks you how she is.

- Friend: I’m planning to ask Susan out this Saturday.

- You: Susan? In Class 104, Susan?

- Friend: Yeah. The girl that always wears nice dresses. What do you think of her? Do you think she’ll say yes?

- You: __________________________________________________________.

- What do you say to your friend to show him that you don’t like Susan? How would you respond to him? Write it in the blank.

- 7.

- Imagine there is a party at your school. Charlie is your close friend and he asks you to go with him to the party. You have an important assignment to give in and you haven’t even started yet, it looks like you won’t be able to go. What do you say to Charlie? Write it in the blank.

- Charlie: Dude? We’re still going to the party on Friday, right?

- You: ______________________________________________________________.

- 8.

- You have just graduated from university and Mary has invited you to her house. You don’t want to go as it’s too far away. What do you say to Mary? How do you reject her invitation? Write it in the blank.

- Mary: You still haven’t told me whether you’re coming on Sunday or not? Are you?

- You: ___________________________________________________________.

- 9.

- Claire is a university student. She is sitting in a café with her Professor talking. Imagine you are the professor. Claire asks you a very personal question. What do you say to her? How do you avoid her question? Write it in the blank.

- Claire: Professor, I was meaning to ask you. I’ve realized that you haven’t been wearing your wedding ring lately. Weren’t you married?

- You: ________________________________________________________________.

- 10.

- Imagine that you are at a family party. You have just started your new job. Everyone has congratulated but your conversation with your uncle goes like this:

- Uncle: Congrats my dear nephew! You’ve always been the clever one.

- You: Thanks uncle!

- Uncle: Look at you, the new CEO of a company! Well done, my man! So, how much will you be getting now? You must earn a fortune!

- You: _____________________________________________.

- What do you say to your uncle? You don’t want to tell him how much money you earn so how do you avoid his question? Write it in the blank.

References

- Thomas, J. Cross-Cultural Pragmatic Failure. Appl. Linguist. 1983, 4, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kasper, G.; Rose, K.R. Pragmatic Development in a Second Language. Lang. Learn. 2002, 52, 1–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kecskes, I. Intercultural Pragmatics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alzeebaree, Y.; Yavuz, M.A. Realization of the Speech Acts of Request and Apology by Middle Eastern EFL Learners. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 13, 7313–7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagherkazemi, M.; Harati-Asl, M. Interlanguage Pragmatic Development: Comparative Impacts of Cognitive and Interpersonal Tasks. Iran. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2022, 10, 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Leech, G.N. Pragmatics, Discourse Analysis, Stylistics and “The Celebrated Letter”. Prose Stud. 1983, 6, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.R.; Kwai-fun, C.N. Pragmatics in Language Teaching: Inductive and Deductive Teaching of Compliments and Compliment Responses. In Pragmatics in Language Teaching; Rose, K., Kasper, G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J. Learning to Talk: Talking to Learn. An Investigation of Learner Performance in Two Types of Discourse. Learn. Teach. Commun. Foreign Lang. Classr. 1986, 52, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimi, D.R. Explicit Instruction and JFL Learners’ Use of Interactional Discourse Markers in Extended Tellings; University of Hawaii: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rızaoğlu, F.; Yavuz, M.A. English Language Learners Comprehension and Production of Implicatures. Eğit. Fak. Derg. 2017, 32, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loranc, B.; Hilliker, S.M.; Lenkaitis, C.A. Virtual Exchange and L2 Pragmatic Development: Analysing Learners’ Formulation of Compliments in L2. Lang. Learn. J. 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelor, J.W. Assessing L2 Pragmatic Proficiency Using a Live Chat Platform: A Study on Compliment Sequences. Lang. Learn. J. 2022, 50, 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, J.M. L2 Pragmatic Comprehension of Aural Sarcasm: Tone, Context, and Literal Meaning. System 2022, 105, 102724. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.D.; Ahn, R.C. Variables That Affect the Dependability of L2 Pragmatics Tests. J. Pragmat. 2011, 43, 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roever, C.; Ellis, R. 7 Testing of L2 Pragmatics: The Challenge of Implicit Knowledge. In New Directions in Second Language Pragmatics; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 142–155. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, H.-Y.; Chen, Y.-S. The Effects of L2 Proficiency on Pragmatic Comprehension and Learner Strategies. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oller, J.W. Language Tests at School: A Pragmatic Approach; Longman: Harlow, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, T.; Detmer, E.; Brown, J.D. A Framework for Testing Cross-Cultural Pragmatics; National Foreign Language Resource Centers: Taibei, Taiwan, 1992; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R. The Definition and Measurement of L2 Explicit Knowledge. Lang. Learn. 2004, 54, 227–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.; Roever, C. The Measurement of Implicit and Explicit Knowledge. Lang. Learn. J. 2021, 49, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteki, B. The Relationship between Implicit and Explicit Knowledge and Second Language Proficiency. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2014, 4, 1520–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardovi-Harlig, K. Developing L2 Pragmatics. Lang. Learn. 2013, 63, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.; Loewen, S.; Elder, C.; Reinders, H.; Erlam, R.; Philp, J. Implicit and Explicit Knowledge in Second Language Learning, Testing and Teaching. In Implicit and Explicit Knowledge in Second Language Learning, Testing and Teaching; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, N. Context, Individual Differences and Pragmatic Competence. In Context, Individual Differences and Pragmatic Competence; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, G.; Rose, K.R. Pragmatics and SLA. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 1999, 19, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. The Effects of Different Levels of Linguistic Proficiency on the Development of L2 Chinese Request Production during Study Abroad. System 2014, 45, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, S. Modelling the Relationships among Interlanguage Pragmatic Development, L2 Proficiency, and Exposure to L2. Appl. Linguist. 2003, 24, 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardovi-Harlig, K.; Rose, M.; Nickels, E.L. The Use of Conventional Expressions of Thanking, Apologizing, and Refusing. In Selected Proceedings of the 2007 Second Language Research Forum; Cascadilla Proceedings Project: Somerville, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, N. Production of Routines in L2 English: Effect of Proficiency and Study-Abroad Experience. System 2013, 41, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieyan, V. Role of Knowledge of Formulaic Sequences in Language Proficiency: Significance and Ideal Method of Instruction. Asian-Pac. J. Second Foreign Lang. Educ. 2018, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Takahashi, S. Pragmalinguistic Awareness: Is It Related to Motivation and Proficiency? Appl. Linguist. 2005, 26, 90–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiao, F. Proficiency Effect on L2 Pragmatic Competence. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2015, 5, 557–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gahtani, S.; Roever, C. Proficiency and Sequential Organization of L2 Requests. Appl. Linguist. 2012, 33, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardovi-Harlig, K.; Dörnyei, Z. Do Language Learners Recognize Pragmatic Violations? Pragmatic versus Grammatical Awareness in Instructed L2 Learning. Tesol Q. 1998, 32, 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dalmau, M.S.; Gotor, H.C. From “Sorry Very Much” to “I’m Ever so Sorry”: Acquisitional Patterns in L2 Apologies by Catalan Learners of English. Intercult. Pragmat. 2007, 4, 287–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, P. Developmental Differences in Speech Act Recognition: A Pragmatic Awareness Study. Lang. Aware. 2004, 13, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, N. Self-qualification in L2 Japanese: An Interface of Pragmatic, Grammatical, and Discourse Competences. Lang. Learn. 2007, 57, 337–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, E.; Basturkmen, H. Evaluating Pragmatics-Focused Materials. ELT J. 2004, 58, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülbeği, E. The Effects of Implicit vs. Explicit Instruction on Pragmatic Development: Teaching Polite Refusals in English. Uludağ Univ. Eğit. Fak. Derg. 2009, 22, 327–356. [Google Scholar]

- Alcón, E. Does Instruction Work for Pragmatic Learning in EFL Contexts. System 2005, 33, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieyan, V. Effect of” Focus on Form” versus” Focus on Forms” Pragmatic Instruction on Development of Pragmatic Comprehension and Production. J. Educ. Pract. 2016, 7, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Holtgraves, T. Interpreting Indirect Replies. Cognit. Psychol. 1998, 37, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, E.L.; Faltz, L.M. Logical Types for Natural Language; Department of Linguistics, UCLA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, N. Comprehending Implied Meaning in English as a Foreign Language. Mod. Lang. J. 2005, 89, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, N. Development of Speed and Accuracy in Pragmatic Comprehension in English as a Foreign Language. Tesol Q. 2007, 41, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaliel, M.E.; Kadim, H. Investigating Iraqi EFL Learners’ Recognition Of Conversational Implicature At The University Level. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 9265–9281. [Google Scholar]

- Samaie, M.; Ariyanmanesh, M. Comprehension of Conversational Implicature in an Iranian EFL Context: A Validation Study. J. Lang. Linguist. Stud. 2018, 14, 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, G.; Rose, K.R. Pragmatics in Language Teaching; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bardovi-Harlig, K.; Griffin, R. L2 Pragmatic Awareness: Evidence from the ESL Classroom. System 2005, 33, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardovi-Harlig, K.; Mahan-Taylor, R. Teaching Pragmatics; Department Office of English Language Programs: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Roever, C. Validation of a Web-Based Test of ESL Pragmalinguistics. Lang. Test. 2006, 23, 229–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziashahabi, S.; Jabbari, A.A.; Razmi, M.H. The Effect of Interventionist Instructions of English Conversational Implicatures on Iranian EFL Intermediate Level Learners’ Pragmatic Competence Development. Cogent Educ. 2020, 7, 1840008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouton, L.F. A Cross-cultural Study of Ability to Interpret Implicatures in English. World Engl. 1988, 7, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouton, L.F. The Interpretation of Implicature in English by NNS: Does It Come Automatically—Without Being Explicitly Taught? Pragmat. Lang. Learn. 1992, 3, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Roever, C. A Web-Based Test of Interlanguage Pragmalinguistic Knowledge: Speech Acts, Routines, Implicatures; University of Hawai’i at Manoa: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, N. Pragmatic Performance in Comprehension and Production of English as a Second Language; Northern Arizona University: Flagstaff, AZ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alrashoodi, S.A. Gender-Based Differences in the Realization of the Speech Act of Refusal in Saudi Arabic; Indiana University: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, J. Inferring Language Change from Computer Corpora: Some Methodological Problems. ICAME J. 1994, 18, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Afriani, N.; Salija, K.; Basri, M. Gender-Based Speech Acts in EFL Online Learning Environment. Pinisi J. Art Humanit. Soc. Stud. 2022, 2, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Niyazova, G.G. Pragmatic Description of Speech Acts Related to Gender Speech. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 5692–5703. [Google Scholar]

- Malki, I. Gender Differences in the Usage of Speech Act of Promise among Moroccan Female and Male High School Students. Intl. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2022, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, B.; Özge, R.; Yavuz, M.A. Comprehension of Conversational Implicatures by Students of the ELT Department. Folklor/Edebiyat 2019, 25, 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Özge, R.; Mohammadzadeh, B.; Yavuz, M.A. Production of Conversational Implicatures by Students of the ELT Department. Folklor/Edebiyat 2019, 25, 424–493. [Google Scholar]

- Trang, T.T.H.; Hoa, N.T.Q. An Investigation into the Flouting of Conversational Maxims Employed by Male and Female Guests in the American Talk Show “The Ellen Show”. Tạp Chí Khoa Học Và Công Nghệ Đại Học Đà Nẵng 2020, 18, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghrabi, H.; Tordjmen, I. Gender Differences in Flouting Conversational Maxims of Algerian Dialectal Arabic Conversations of Students of English at Ibn Khaldoun University of Tiaret, Université Ibn Khaldoun-Tiaret. Master’s Thesis, Ibn Khaldoun University, Tiaret, Algeria, 2019. Available online: http://dspace.univ-tiaret.dz:8080/jspui/handle/123456789/1016 (accessed on 25 December 2022).

- Barzani, S.; Mohammadzadeh, B. Retracted Article: Pragmatic Competence: An Imperative Competency for a Safe and Healthy Communication. Appl. Nanosci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Qassim, T.; Fadhil Abbas, N.; Falih Ahmed, F.; Hameed, S. Pragma-Linguistic and Socio-Pragmatic Transfer among Iraqi Female EFL Learners in Refusing Marriage Proposals. Arab World Engl. J. 2021, 12, 521–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifantidou, E. Genres and Pragmatic Competence. J. Pragmat. 2011, 43, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. Symbolic Representation and Attentional Control in Pragmatic Competence. Interlang. Pragmat. 1993, 3, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Grice, H.P. Logic and Conversation. In Speech Acts; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1975; pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, A. A Critical Appraisal of Grice’s Cooperative Principle. Open J. Mod. Linguist. 2013, 3, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Searle, J.R.; Searle, J.R. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1969; Volume 626. [Google Scholar]

- Kubota, M. Teachability of Conversational Implicature to Japanese EFL Learners. IRLT Inst. Res. Lang. Teach. Bull. 1995, 9, 35–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.S. Interpreting Conversational Implicatures: A Study of Korean Learners of English. Korea TESOL J. 2002, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Aijmer, K. Contrastive Pragmatics; John Benjamins Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Eslami, Z.R.; Mirzaei, A. Speech Act Data Collection in a Non-Western Context: Oral and Written DCTs in the Persian Language. Int. J. Lang. Test. 2014, 4, 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Bardovi-Harlig, K.; Shin, S.-Y. Expanding Traditional Testing Measures with Tasks from L2 Pragmatics Research. Int. J. Lang. Test. 2014, 4, 26–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cetinavci, U.R.; Öztürk, I. The Development of an Online Test to Measure the Interpretation of Implied Meanings as a Major Constituent of Pragmatic Competence; ERIC: Online Submission, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Hungler, P.B. Nursing Research: Principles & Methods, 6th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, G. Narrative Inquiry. In Qualitative Research in Applied Linguistics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, N. Cognition, Language Contact, and the Development of Pragmatic Comprehension in a Study-abroad Context. Lang. Learn. 2008, 58, 33–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghi, M.; Kazemi, S.A.; Kalani, A. The Effect of Gender on Language Learning. J. Nov. Appl. Sci. 2013, 2, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Pourshahian, B. A Gender-Based Analysis of Refusals as a Face Threatening Act: A Case Study of Iranian EFL Learners. Int. J. Linguist. Lit. Transl. 2019, 2, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kasanga, L.A. Effect of Gender on the Rate of Interaction. Some Implications for Second Language Acquisition and Classroom Practice. ITL-Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 1996, 111, 155–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegal, M. The Role of Learner Subjectivity in Second Language Sociolinguistic Competency: Western Women Learning Japanese. Appl. Linguist. 1996, 17, 356–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loban, W. Language of Elementary School Children: A Study of the Use and Control of Language and the Relations among Speaking, Reading, Writing, and Listening; National Council of Teachers of English: Champaign, IL, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton, L.F. Can NNS Skill in Interpreting Implicature in American English Be Improved through Explicit Instruction?—A Pilot Study; ERIC Clearinghouse: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

| Level | Male | Female | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate Plus (C1) | 6 | 14 | 20 |

| Intermediate (B2) | 13 | 21 | 34 |

| Total | 54 |

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | p | Std. Error Mean | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCT | 54 | 61.54 | 8.89 | 0.0123 | 1.21 | p < 0.05 |

| MCDT | 54 | 66.46 | 12.49 | 1.70 |

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | p | Std. Error Mean | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 20 | 70.20 | 12.08 | 0.0920 | 2.70 | p > 0.05 |

| B2 | 34 | 64.26 | 12.37 | 2.12 |

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | p | Std. Error Mean | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 20 | 61.65 | 9.26 | 0.5647 | 2.07 | p > 0.05 |

| B2 | 34 | 60.21 | 8.56 | 1.47 |

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | p | Std. Error Mean | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 19 | 64.07 | 10.15 | 0.8979 | 2.33 | p > 0.05 |

| Female | 35 | 63.74 | 8.30 | 1.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kentmen, H.; Debreli, E.; Yavuz, M.A. Assessing Tertiary Turkish EFL Learners’ Pragmatic Competence Regarding Speech Acts and Conversational Implicatures. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043800

Kentmen H, Debreli E, Yavuz MA. Assessing Tertiary Turkish EFL Learners’ Pragmatic Competence Regarding Speech Acts and Conversational Implicatures. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043800

Chicago/Turabian StyleKentmen, Hazel, Emre Debreli, and Mehmet Ali Yavuz. 2023. "Assessing Tertiary Turkish EFL Learners’ Pragmatic Competence Regarding Speech Acts and Conversational Implicatures" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043800