Age Simulation Suits in Education and Training of Staff for the Nautical Tourism Sector

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Senior Tourism as Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals—SDGs

2.2. Education of Marina Personnel

2.3. The Age Simulation Suit as a Teaching Tool

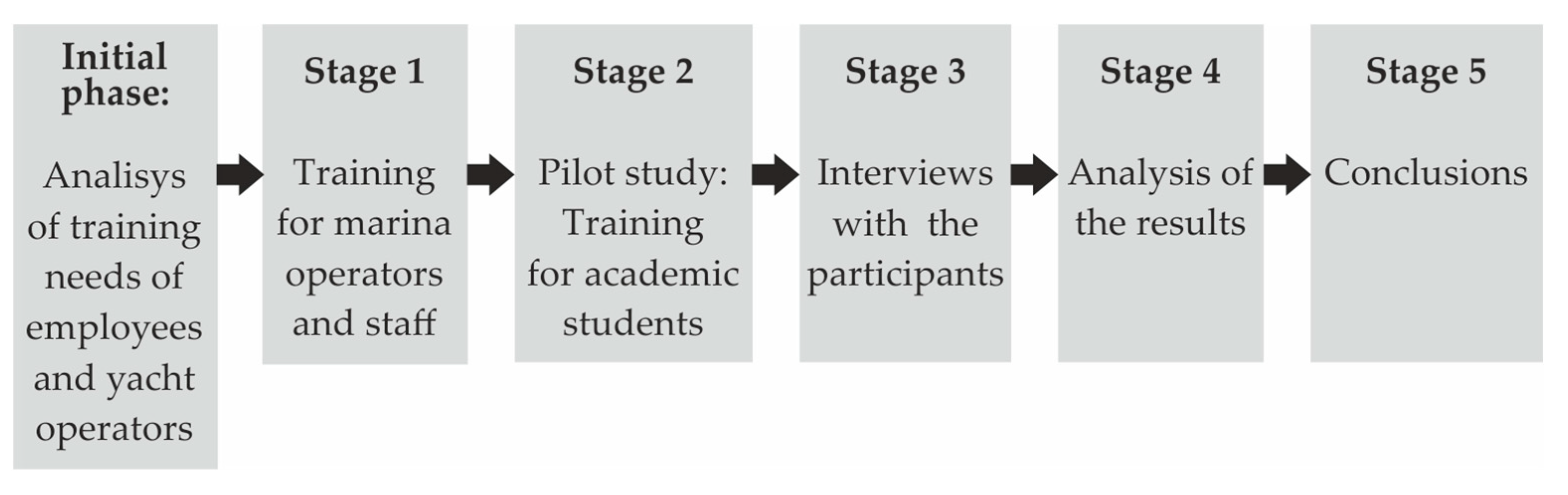

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Initial Phase

| No. | Topic | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marketing in marinas: What to do alone at a marina? What to do together with others at a destination? The importance of social media for the development of nautical tourism (how it works, how it can be used, who the users are). | 66 |

| 2 | Trends in nautical tourism | 69 |

| 3 | Yacht ports for everyone: How can they be adapted to the needs of elderly sailors, the disabled, and families with children? | 71 |

| 4 | Information and its importance, i.e., how to organise a tourist information point in the port, how to train staff, but also information flow in the port and between SCB ports, specifically what information should look like and why. | 69 |

| 5 | Review of selected sailing regulations in Poland, Germany, Denmark, and Lithuania (e.g., when a person can board a yacht, when to call for services, what data can be requested from sailors) | 68 |

| 6 | How to welcome a tourist (‘Savoir faire’ of sailing, basic phrases, how to safely moor a yacht) | 69 |

| 7 | How to deal with a difficult client? | 63 |

| 8 | Building a yacht | 50 |

| 9 | Review of selected sailing regulations in Poland, Germany, Denmark, and Lithuania (e.g., when a person can board a yacht, when to call for services, what data can be requested from sailors) | 68 |

3.2. Stage 1

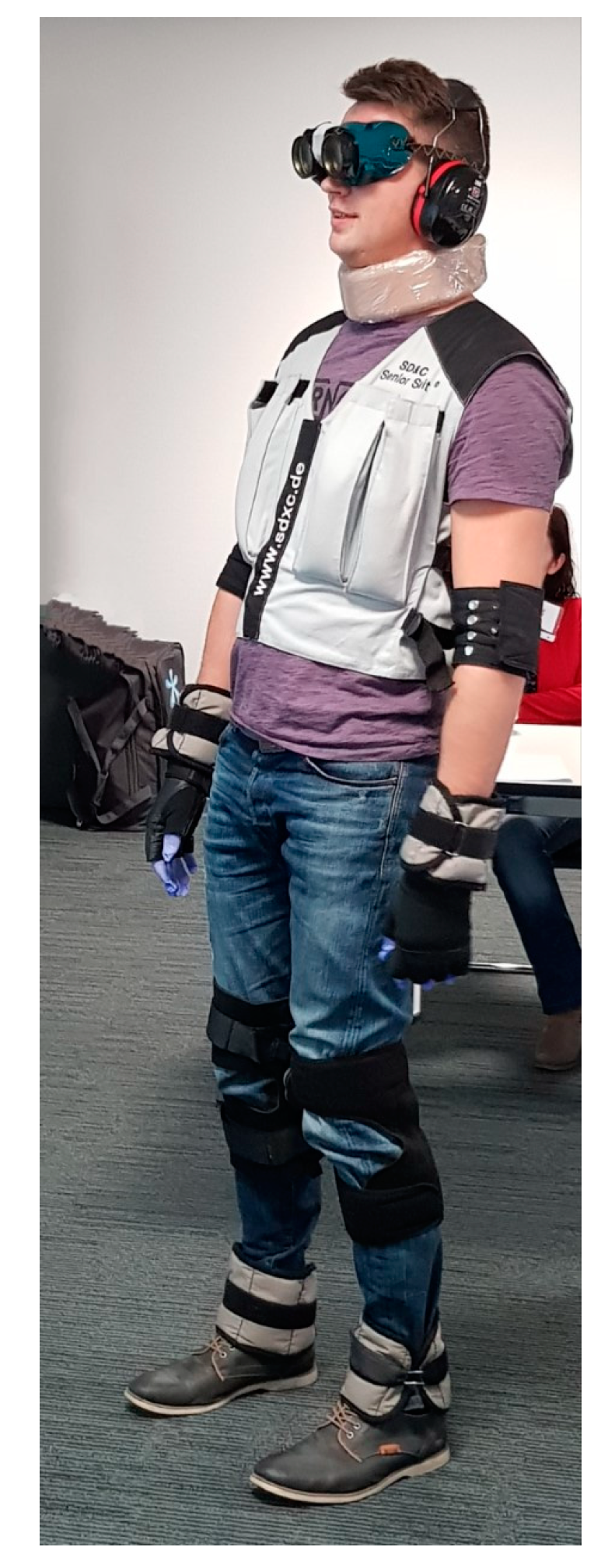

3.3. Stage 2

| Accessories | Simulated Physical Problem(s) | Simulated Sensory Problem(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Goggles | - | Deterioration in visual quality: narrowing of the viewing angle, impaired color recognition, impaired visual acuity |

| Knee and wrist weights | Knee and wrist weights | - |

| Neck, knee, and elbow restraints | Joint stiffness, the stooped posture of an elderly person | - |

| Earplugs | - | Deterioration of hearing quality |

| Neck collar | Neck stiffness, limited neck movement | - |

| Gloves | Decreased hand dexterity | - |

| Slippers | Cautious gait pattern | - |

- Open and close the door with a key;

- Go down and up the stairs;

- Go down and take the lift;

- Read an informative text;

- Count coins and choose the correct amount;

- Get up from a lying position.

3.4. Stages 3–5

4. Results

- Difficulties in embarking and disembarking from a boat (I);

- Mooring (O);

- Overcoming a difference in levels (e.g., when moving from the wharf to the pier or climbing stairs) (I);

- Long distances to sanitary facilities (O);

- Problems with the use of utilities (e.g., electricity, water); handling utility stands (I).

- Uneven surfaces (e.g., holes in the pavement and other damage) (I);

- Problems with moving around the port at night (poor vision in the dark) (A);

- Walking on narrow platforms (I);

- Slippery surfaces (I);

- Carrying things to the yacht (e.g., when mooring or leaving the yacht) (A);

- Problems with traveling to the city (poor accessibility of public transport) (I).

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raport Tematyczny PARP 2020, System Rad ds. Kompetencji. Available online: https://www.parp.gov.pl/storage/publications/pdf/Starzenie_sie_spoleczenstw.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Population Projection 2014–2050. Available online: http://www.stat.gov.pl/.CentralStatisticalOffice (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Report Ageing Europe. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Ageing_Europe_-_statistics_on_population_developments.Statisticsonpopulationdevelopments (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/population-ageing (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Report. Polski Rynek Żeglarski. 2016. Available online: http://portalzeglarski.com/news_sailportal,6699.html (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Report. Wassertourismus in Deutschland. 2014. Available online: https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Tourismus/wassertourismus-in-deutschland.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Huber, D.; Milne, S.; Hyde, K.F. Constraints and facilitators for senior tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 27, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hącia, E.; Łapko, A. Staff training for the purposes of marina management. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Wrocławiu 2019, 63, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, R.; Yepes, V. Economic valuation of landscape in marinas: Application to a marina in Spanish Southern Mediterranean coast (Granada, Spain). Land 2022, 11, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, R.; Yepes, V. Assessing the relationship between landscape and management within marinas: The managers’ perception. Land 2022, 11, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sert, A.N. Senior Tourism in the aging world, In: Theory and Practice in Social Sciences; Krystev, V., Efe, R., Atasoy, E., Eds.; St. Kliment, Ohridski University Press: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2019; pp. 488–498. [Google Scholar]

- Berbeka, J. Ocena konsumpcji w Polsce w świetle założeń zrównoważonej konsumpcji. In Konsumpcja i Rynek w Warunkach Zmian Systemowych; Kędzior, Z., Kieżel, E., Eds.; Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 2002; pp. 102–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kotowska, I. Żegluga Morska Bliskiego Zasięgu w Świetle Idei Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Transportu; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Akademii Morskiej w Szczecinie: Szczecin, Poland, 2014; pp. 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Norouzi, N.; Ataei, E. Globalization and sustainable development. Int. J. Innov. Res. Humanit. 2021, 1, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Kielesińska, A. Paradygmat zrównoważonego rozwoju w odpowiedzialności społecznej biznesu. Przedsiębiorczość Zarządzanie 2019, 20, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Report. The Sustainable Development Goals ReportThe Sustainable Development Goals Report. 2022. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 11 September 2022).

- Streimikiene, D.; Svagzdiene, B.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A. Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczak, M. Jaką aksjologię zakłada idea zrównoważonego rozwoju w turystyce. Tur. Rekreac. Stud. Pr. 2010, 6, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Darcy, S.; Dickson, T. A Whole-of-Life Approach to Tourism: The Case for Accessible Tourism Experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2009, 16, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patterson, I.; Balderas-Cejudo, A.; Pegg, S. Tourism preferences of seniors and their impact on healthy ageing. Anatolia Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 32, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: A new conceptual model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 31, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roult, R.; Carbonneau, H.; Adjizian, J.M.; Belley-Ranger, É. Case study regarding the interests and leisure practices of persons aged 50 and over in Saint-Léonard, suburb of Montreal: Seniors vs. baby boomers. Pol. J. Sport Tour. 2016, 23, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taloş, A.M.; Lequeux-Dincă, A.I.; Preda, M.; Surugiu, C.; Mareci, A.; Vijulie, I. Silver tourism and recreational activities as possible factors to support active ageing and the resilience of the tourism sector. J. Settl. Spat. Plan. 2021, 8, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puscasu, V. Silver tourism as a possible factor for regional development. a case study in the south-east region of Romania. Rev. Tur. Stud. Cercet. Tur. 2017, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zsarnoczky, M. Developing senior tourism in Europe. Pannon Manag. Rev. 2017, 6, 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Zangerl, T.; Gattringer, C.; Groth, A.; Mirski, P. Silver Surfers & eTourism: Web Usability and Testing Methods for the Generation 50plus. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2011; Law, R., Fuchs, M., Ricci, F., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2011; pp. 75–87. 50p. [Google Scholar]

- Stončikaitė, I. Baby-boomers hitting the road: The paradoxes of the enior leisure tourism. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2021, 20, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, G.M.; Ivaldi, E. Tourist ports and yachting: The case of Sardinia. Rev. Estud. Andal. 2017, 34, 429–452. [Google Scholar]

- Edelheim, J. How should tourism education values be transformed after 2020? Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammedrisaevna, T.M.; Shukrullaevich, A.F.; Bakhriddinovna, A.N. The logistics approach in managing a tourism company. Res. Jet J. Anal. Invent. 2021, 2, 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Strulak-Wójcikiewicz, R.; Wagner, N.; Łapko, A.; Hącia, E. Applying the business model canvas to design the E-platform for sailing tourism. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 176, 1643–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.M.; Chen, S.H.; Chen, T.F. The relationships among experiential marketing, service innovation, and customer satisfaction—A case study of tourism factories in Taiwan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, S.; Singh, V. Soft Skills in Tourism-A case study of Tourism Management Graduates. IJRAR Int. J. Res. Anal. Rev. 2020, 7, 430–437. [Google Scholar]

- Kiryakova-Dineva, T.; Kyurova, V.; Chankova, Y. Soft skills for sustainable development in tourism: The Bulgarian experience. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summak, M.E. A Study on the communication and emphatic skills of the students having education on tourism sector. J. Inst. Soc. Sci. 2014, 31, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Gillovic, B.; McIntosh, A. Accessibility and inclusive tourism development: Current state and future agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcover, A.; Alemany, M.; Jacob, M.; Payeras, M.; García, A.; Martínez-Ribes, L. The economic impact of yacht charter tourism on the Balearic economy. Tour. Econ. 2011, 17, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, S. An overview of yachting tourism and its role in the development of coastal areas of Croatia. J. Hosp. Tour. Issues 2019, 1, 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nowaczyk, P. Direct and indirect impact of nautical tourism on the development of local economy in West Pomerania on the example of Darłowo municipality. Acta Sci. Pol. Oecon. 2018, 17, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinno, L.; Zanini, A. The development of pleasure boating and yacht harbours in the Mediterranean Sea: The case of the Riviera ligure. Int. J. Marit. Hist. 2010, 22, 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hącia, E.; Łapko, A. Territorial cooperation for the development of nautical tourism in the Southern Baltic Rim. In Proceedings of the DIEM: Dubrovnik International Economic Meeting Sveučilište u Dubrovniku, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 12–14 October 2017; Volume 3, pp. 780–792. [Google Scholar]

- Favro, S.; Gržetić, Z.; Kovačić, M. Towards sustainable yachting in Croatian traditional island ports. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2010, 9, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luković, T.; Šerić, N. Strategic development and changes in legislation regulating yachting in Croatia. Pomorstvo 2009, 23, 357–374. [Google Scholar]

- Poletan Jugović, T.; Agatić, A.; Gračan, D.; Šekularac–Ivošević, S. Sustainable activities in Croatian marinas–towards the “green port” concept. Pomorstvo 2022, 36, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łapko, A. The use of auxiliary electric motors in boats and sustainable development of nautical tourism–cost analysis, the advantages and disadvantages of applied solutions. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 16, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S.; Rahi, M. Energy Harvesting and Storage System for Marine Applications. Int. J. Energy Power Eng. 2019, 13, 182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Sariisik, M.; Turkay, O.; Akova, O. How to manage yacht tourism in Turkey: A swot analysis and related strategies. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Içemer, G.T.; Can, E.; Atasoy, L.; Yildirim, U.B. The Effects of Yacht Activities on Sea Water Quality. J. Coast. Res. 2011, 61, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgen, D.; Alpaslan, M.N.; Serifoglu, A.G. Best waste management programs (BWMPs) for marinas: A case study. J. Coast. Conserv. 2003, 9, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favro, S.; Kovačić, M. Construction of marinas in the Croatian coastal cities of Split and Rijeka as attractive nautical destinations. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2015, 148, 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacic, M.; Grzetic, Z.; Boskovic, D. Nautical tourism in fostering the sustainable development: A case study of Croatia’s coast and island. Tourismos 2011, 6, 221–232. [Google Scholar]

- Appolloni, L.; Sandulli, R.; Vetrano, G.; Russo, G.F. A new approach to assess marine opportunity costs and monetary values-in-use for spatial planning and conservation; the case study of Gulf of Naples, Mediterranean Sea, Italy. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2018, 152, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, S.; Vlasic, D. Developing a benchmarking methodology for marina business. Tour. Mar. Environ. 2018, 13, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevolo, C.; Spinelli, R. Benefit segmentation of pleasure boaters in Mediterranean marinas: A proposal. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lučić, L.; Luković, T. Controlling as a function of successful management of a marina. In Proceedings of the DIEM: Dubrovnik International Economic Meeting Sveučilište u Dubrovniku, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 12–14 October 2017; Volume 3, pp. 469–479. [Google Scholar]

- Branowski, B.; Zabłocki, M.; Gabryelski, J.; Walczak, A.; Kurczewski, P. Hazard analysis of a yacht designed for people with disabilities. Int. Shipbuild. Prog. 2021, 68, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivošević, S.Š.; Milošević, D. An Analysis of Qualifications and Personal Characteristics of Successful Marina Manager. Časopis Pomor. Fak. Kotor J. Marit. Sci. 2022, 23, 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Labajos, C.Á.; Blanco Rojo, B.; Sánchez, L.; Madariaga, E.; Díaz, E.; Torre, B.; Sanfilippo, S. The leisure nautical sector in the atlantic area. J. Marit. Res. 2014, XI, 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Vieweg, J.; Schaefer, S. How an age simulation suit affects motor and cognitive performance and self-perception in younger adults. Exp. Aging Res. 2020, 46, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauenroth, A.; Schulze, S.; Ioannidis, A.; Simm, A.; Schwesig, R. Effect of an age simulation suit on younger adults’ gait performance compared to older adults’ normal gait. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2017, 10, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.L.S.; Ma, P.K.; Lam, Y.Y.; Ng, K.C.; Ling, T.K.; Yau, W.H.; Chui, Y.W.; Tsui, H.M.; Li, P.P. Effects of Senior Simulation Suit Programme on nursing students’ attitudes towards older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 88, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, T.; Chester, L.; Fernando, M.; Jebreel, A.; Devine, M.; Bhat, M. Improving medical student empathy: Initial findings on the use of a book club and an old age simulation suit. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 41, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Parola, V.; Cardoso, D.; Duarte, S.; Almeida, M.; Apóstolo, J. The use of the aged simulation suit in nursing students: A scoping review. J. Nurs. Ref. 2017, 4, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, C.; Higham, E.; Townley, C.; Gilfoyle, M. Can age suit simulation enable physiotherapy students to experience and understand the specific challenges to balance experienced by older adults? Physiotherapy 2019, 105, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Kwon, H. Long-term effects of an aging suit experience on nursing college students. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 50, 102923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossler, K.L.; Tucker, C. Simulation helps equip nursing students to care for patients with dementia. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2022, 17, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, D.; Taskiran, N.; Baysal, E.; Acar, E.; Cevik Akyil, R. Effect of an aged simulation suit on nursing students’ attitudes and empathy. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 11, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.W.H.; Teh, P.L. “Suiting Up” to enhance empathy toward aging: A randomized controlled study. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.; Stone, R.; Cox, L. Customer needs extraction using disability simulation for purposes of inclusive design. In Proceedings of the ASME 2014 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, New York, NY, USA, 17–20 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kullman, K. Prototyping bodies: A post-phenomenology of wearable simulations. Des. Stud. 2016, 47, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minegishi, Y. Experimental study of the walking behavior of crowds mixed with slow-speed pedestrians as an introductory study of elderly-mixed evacuation crowds. Fire Saf. J. 2021, 120, 103041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydzik, R. W skórze drugiego człowieka—Empatyzacja na poziomie sensorycznym stosowana jako narzędzie projektowe. Dzienn. Media 2020, 13, 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Price, P.C.; Jhangiani, R.; Chiang, I.C.A. Research Methods in Psychology; BCCampus, California State University: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2015; p. 130. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan, M.; Rosinger, K.; Ahn, J.B. Use of quasi-experimental research designs in education research: Growth, promise, and challenges. Rev. Res. Educ. 2020, 44, 218–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C.; Yu, C.C.; Hsieh, P.L.; Li, C.C.; Chao, Y.F.C. Situated teaching improves empathy learning of the students in a BSN program: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 64, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas-Sarmiento, P.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, M.; Baena-Baños, M.; Romero-Sánchez, J.M. Efficacy of empathy training in nursing students: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 59, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Wang, L.; Sun, J.; Li, D.Y.; Zheng, B.Y.; He, S.W.; Zhu, L.-h.; Latour, J.M. Effectiveness of empathy clinical education for children’s nursing students: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 85, 104260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: http://www.marinas.pl. (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Available online: http://zmigm.org.pl (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Available online: https://www.sakamoto-model.com/product/simulation/m176/ (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Mensah, J. Sustainable development: Meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: Literature review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1653531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsarnoczky, M.; David, L.; Mukayev, Z.; Baiburiev, R. Silver tourism in the European Union. GeoJournal Tour. Geosites 2016, 18, 224–232. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, C.; Brochado, A.; Correia, A. Seniors in international residential tourism: Looking for quality of life. Anatolia. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 29, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, H. Educating for Understanding. Am. Sch. Board J. 1993, 180, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vare, P.; Scott, W. Learning for a change: Exploring the relationship between education and sustainable development. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 1, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Drolon, E.; Verneuil, L.; Manolios, E.; Revah-Levy, A.; Sibeoni, J. Medical students’ perspectives on empathy: A systematic review and metasynthesis. Acad. Med. 2020, 96, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Infrastructure-Related (I) | Action-Related (A) | Organization-Related (O) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Łapko, A. Age Simulation Suits in Education and Training of Staff for the Nautical Tourism Sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043803

Łapko A. Age Simulation Suits in Education and Training of Staff for the Nautical Tourism Sector. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043803

Chicago/Turabian StyleŁapko, Aleksandra. 2023. "Age Simulation Suits in Education and Training of Staff for the Nautical Tourism Sector" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043803