Sustainable Business Model Design: A Multi-Case Approach Exploring Generic Strategies and Dynamic Capabilities on the Example of German Wine Estates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Environment, Strategic Positioning and Business Models

2.2. A Strategic Approach to Sustainability Innovation

2.3. Dynamic Capabilities for Strategic and Sustainable Management

2.4. Implementation of Sustainability in the Wine Industry

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

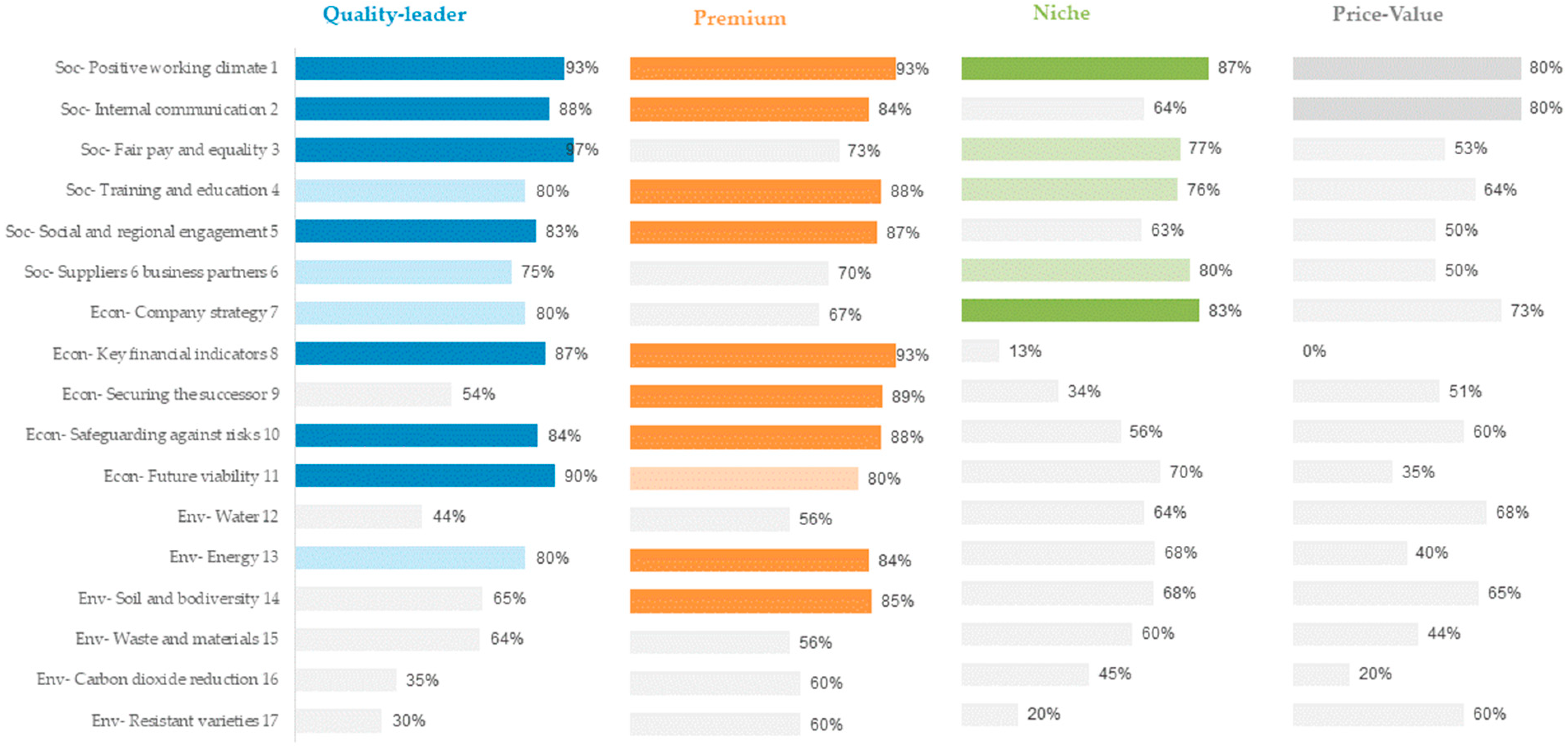

4.1. Dynamic Capabilities for Social Sustainability

4.2. Dynamic Capabilities for Economic Sustainability

4.3. Dynamic Capabilities for Environmental Sustainability

4.4. Additional Cross-Strategy Results

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Perspectives for Research

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahlstrom, D.; Arregle, J.L.; Hitt, M.A.; Qian, G.; Ma, X.; Faems, D. Managing technological, sociopolitical, and institutional change in the new normal. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 57, 411–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M. Generic strategic profiling of entrepreneurial SMEs–environmentalism as hygiene factor. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2022, 19, 121–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Castrogiovanni, G.J.; Ribeiro, D.; Roig, S. Linking entrepreneurship and management: Welcome to the International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2005, 1, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, L. Profiting from green innovation: The moderating effect of competitive strategy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panarello, D. Economic insecurity, conservatism, and the crisis of environmentalism: 30 years of evidence. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 73, 100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-de Castro, G. Exploring the market side of corporate environmentalism: Reputation, legitimacy and stakeholders’ engagement. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 92, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, P.J.H.; Heaton, S.; Teece, D. Innovation, Dynamic Capabilities, and Leadership. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 61, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Y. Defining, conceptualizing, and measuring organizational resilience: A multiple case study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.L.; Manuel, E.C.; Dutschke, G.; Pereira, R.; Pereira, L. Economic crisis effects on SME dynamic capabilities. Int. J. Learn. Chang. 2021, 13, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarazzo, M.; Penco, L.; Profumo, G.; Quaglia, R. Digital transformation and customer value creation in Made in Italy SMEs: A dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannas, R. Exploring digital transformation and dynamic capabilities in agrifood SMEs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Hansen, E.G. Business models for sustainability: A co-evolutionary analysis of sustainable entrepreneurship, innovation, and transformation. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 264–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amui, L.; Jabbour, C.; Jabbour, A.; Kannan, D. Sustainability as a dynamic organizational capability: A systemic review and a future agenda toward a sustainable transition. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.J.; Ratten, V.; Dana, L.-P. Knowledge spillover-based strategic entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Towards a dynamic theory of strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esty, C.D.; Porter, M.E. National environmental performance: An empirical analysis of policy results and determinants. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2005, 10, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, L.; Filippini, R. Organizational and managerial challenges in the path toward Industry 4.0. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Is the Resource-Based View a Useful Perspektive for Strategic Management? Yes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.; Wright, M.; Ketchen, D.J. The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, G.N.; Hanks, S.H. Market Attractiveness, Resource-Based Capabilities, Venture Strategies, and Venture Performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 1994, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranieri, S.; Varacca, A.; Casati, M.; Capri, E.; Soregaroli, C. Adopting environmentally-friendly certifications: Transaction cost and capabilities perspectives within the Italian wine supply chain. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2021, 27, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.S.; Bright, D.; Caza, A. Exploring the relationships between organizational virtuousness and performance. Am. Behav. Sci. 2004, 47, 766–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullough, A.; Renko, M. Entrepreneurial resilience during challenging times. Bus. Horiz. 2013, 56, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallak, L. Putting organizational resilience to work. Ind. Manag. 1998, 4, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Rai, B.K.; Griffin, M. Resilience and competitiveness of small and medium size enterprises: An empirical research. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5489–5509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, A.; Savelsberg, E. Ulrich DorndorfAgile Optimierung in Unternehmen; Haufe Verlag: Baden-Württemberg, Germany, 2018; 176 S., 29,95 Euro; ISBN 978-3-648-11135-2. [Google Scholar]

- Annarelli, A.; Nonino, F. Strategic and operational management of organizational resilience: Current state of research and future directions. Omega 2016, 62, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, B. Strategy, organization and leadership in a new “transient-advantage” world. Strategy Leadersh. 2014, 42, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goumagias, N.; Fernandes, K.; Cabras, I.; Li, F.; Shao, J.; Devlin, S.M.; Hodge, V.J.; Cowling, P.I.; Kudenko, D. A Conceptual Framework of Business Model Emerging Resilience. In Proceedings of the 32nd European Group for Organization Studies (EGOS) Colloquium, Naples, Italy, 7–9 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Veliyath, R.; Fitzgerald, E. Firm capabilities, business strategies, customer preferences, and hypercompetitive arenas: The sustainability of competitive advantages with implications for firm competitiveness. Bus. J. Inc. J. Glob. Compet. 2000, 10, 56–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, V.; Lioukas, S.; Chambers, D. Strategic decision-making processes: The role of management and context. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 115–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P. The role of corporations in achieving ecological sustainability. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 936–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortun, K. Advocacy after Bhopal: Environmentalism, Disaster, New Global Orders; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, R.; Kaplan, S. Creative Destruction: Why Companies That Are Built to Last Underperform the Market; Crown Business: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Croitoru, G.; Duica, M.; Robescu, O.; Valentin, R.; Oprisan, O. Entrepreneurial resilience, factor of influence on the function of entrepreneur. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference Risk in Contemporary Economy, Galati, Romania, 9–10 June 2017; pp. 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, J.-C.; Manzano, G. The resilience of the entrepreneur. Influence on the success of the business. A longitudinal analysis. J. Econ. Psychol. 2014, 42, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islami, X.; Mustafa, N.; Latkovikj, M.T. Linking Porter’s generic strategies to firm performance. Future Bus. J. 2020, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegenbaum, A.; Thomas, H. Strategic Groups and Performance: The US Insurance Industry; University of Michigan, School of Business Administration: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. The structural and environmental correlates of business strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1987, 8, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Configurations of strategy and structure: Towards a synthesis. Strateg. Manag. J. 1986, 7, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.T.B.; Deborah, J.; Keong Leong, G. Configurations of manufacturing strategy, business strategy, environment and structure. J. Manag. 1996, 22, 597–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.T.D.; Rebecca. Manufacturing strategy in context: Environment, competitive strategy and manufacturing strategy. J. Oper. Manag. 2000, 18, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. From Competitive Advantage to Corporate Strategy. In Readings in Strategic Management; Asch, D., Bowman, C., Eds.; Palgrave: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. What is strategy? In Strategy for Business: A Reader; Mazzucato, M., Ed.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Hunt, C. What have we learned about generic competitive strategy? A meta-analysis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 127–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Location, Competition, and Economic Development: Local Clusters in a Global Economy. Econ. Dev. Quaterly 2000, 14, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappel, S.; Pearson, T.; Romero, E. Strategic Group Performance in the Commercial Airline Industry—Strategic Response to Structural Disequilibrium. J. Manag. Res. 2003, 3, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cool, K.; Dierickx, I. Rivalry, strategic groups, and performance. SMJ 1993, 16, 461–476. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G.; Thomas, H. The industry context of strategy, structure and performance: The UK brewing industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 1987, 8, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, G.S.; Chales, C.; Sharfman, M.P. Industry variety and performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deimel, K. Stand der strategischen Planung in kleinen und mittleren Unternehmen in der BRD. Z. Für Plan. Unternehm. 2008, 19, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, T.M.; Miller, W.D. Small-firm competitive strategy. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 10, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.; Coelho, A.; Moutinho, L. Dynamic capabilities, creativity and innovation capability and their impact on competitive advantage and firm performance: The moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Technovation 2020, 92, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, K.-H.; Güldenberg, S. Generic strategies and firm performance in SMEs: A longitudinal study of Austrian SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2010, 35, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verreynne, M.; Meyer, D. Small business strategy and the industry life cycle. Small Bus. Econ. 2010, 35, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inderhees, P. Strategische Unternehmensführung Landwirtschaftlicher Haupterwerbsbetriebe: Eine Untersuchung am Beispiel Nordrhein-Westfalens; Niedersächsische Staats-und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Winfree, J.A.; McCluskey, J.J. Collective Reputation and Quality. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2005, 87, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegenbaum, A.; Thomas, H. Strategic groups as reference groups: Theory, modeling and empirical examination of industry and competitive strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Ahmed, P.K. Dynamic capabilities: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fielt, E. Conceptualising business models: Definitions, frameworks and classifications. J. Bus. Model. 2013, 1, 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, A.J.; Warglien, M.; George, G. A simulation-based approach to business model design and organizational Change. Innovation 2021, 23, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Zheng, X.; Fan, D.; Zhang, P.; Li, S. The sharing economy and business model design: A configurational approach. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 949–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtström, J. Business model innovation under strategic transformation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 34, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, D. Stakeholder ties, organizational learning, and business model innovation: A business ecosystem perspective. Technovation 2022, 114, 102445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Wang, L. How companies configure digital innovation attributes for business model innovation? A configurational view. Technovation 2022, 112, 102398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M.; Paunovic, I. Sensing technologies, roles and technology adoption strategies for digital transformation of grape harvesting in SME wineries. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Ortiz, J. Sustainable business modeling: The need for innovative design thinking. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Mosavi, A.; Shamshirband, S.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Rakotonirainy, A.; Chau, K.W. Sustainable business models: A review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, T.; Gilinsky, A.; Newton, S.K. Sustainability in the Wine Industry: Altering the Competitive Landscape? In Proceedings of the AWBR International Conference, Bordeaux, France, 9–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Benson-Rea, M.; Woodfield, P.; Brodie, R.J.; Lewis, N. Sustainability in strategy: Maintaining a premium position for New Zealand wine. In Proceedings of the 6th AWBR International Conference, Bordeaux, France, 9–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, S.L.; Cullen, R.; Grout, R. Adoption of environmental innovations: Analysis from the Waipara wine industry. Wine Econ. Policy 2013, 2, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmenti, E.; Migliore, G.; Di Franco, C.P.; Borsellino, V. Is there sustainable entrepreneurship in the wine industry? Exploring Sicilian wineries participating in the SOStain program. Wine Econ. Policy 2016, 5, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogonos, M.; Engler, B.; Oberhofer, J.; Dressler, M.; Dabbert, S. Planting Rights Liberalization in the European Union: An Analysis of the Possible Effects on the Wine Sector in Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany. Ger. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 65, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Malheiro, A.C.; Santos, J.A.; Fraga, H.; Pinto, J.G. Climate change scenarios applied to viticultural zoning in Europe. Clim. Res. 2010, 43, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzard, J.-M. Innovation Systems and Regional Vineyards. In Proceedings of the ISDA, Montpellier, France, 28 June–1 July 2010; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Loose, S.; Pabst, E. Current State of the German and International Wine Markets. Oceania 2018, 92–101. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwi09Jaru6X9AhWOat4KHY6SAusQFnoECAgQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.researchgate.net%2Fprofile%2FSimone-Mueller-Loose-2%2Fpublication%2F323402029_Current_state_of_the_German_and_international_wine_markets%2Flinks%2F5a947195aca2721405674a95%2FCurrent-state-of-the-German-and-international-wine-markets.pdf&usg=AOvVaw3B9przccjRU1kknTGnpklK (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Bartunek, J.M.; Rynes, S.L.; Ireland, R.D. What makes management research interesting, and why does it matter? Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilduff, M. Editor’s comments: Publishing theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R. From the editors: What grounded theory is not. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. The new field of sustainable entrepreneurship: Studying entrepreneurial action linking “what is to be sustained” with “what is to be developed”. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Reinventing marketing to manage the environmental imperative. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berns, M.; Townend, A.; Khayat, Z.; Balagopal, B.; Reeves, M.; Hopkins, M.S.; Krushwitz, N. Sustainability and competitive advantage. Sloan Manag. Rev. 2009, 51, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. Two decades of sustainability management tools for SMEs: How far have we come? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, D.J. Entrepreneurship, small and medium sized enterprises and public policies. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research; Acs, Z.J., Audretsch, D.B., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 473–511. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Entrepreneurship and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs); European Commission: Hong Kong, China, 2018; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes_en (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Santini, C.; Cavicchi, A.; Casini, L. Sustainability in the wine industry: Key questions and research trends. Agric. Food Econ. 2013, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M.M.; Apaydin, M. A Multi-Dimensional Framework of Organizational Innovation: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1154–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scozzi, B.; Garavelli, C.; Crowston, K. Methods for modeling and supporting innovation processes in SMEs. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2005, 8, 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilinsky, A.; Santini, C.; Lazzeretti, L.; Eyler, R. Desperately seeking serendipity. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2008, 20, 302–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama, R.; Tunzelmann, N.v. Empirical Studies of Innovation in the Food and Beverage Industry. In Handbook of Innovation in the Food and Drink Industry; Rama, R., Ed.; The Haworth Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008; pp. 13–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lubell, M.; Hillis, V.; Hoffman, M. Innovation, Cooperation, and the Perceived Benefits and Costs of Sustainable Agriculture Practices. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsman, H. Innovation capacity and innovation development in small enterprises. A comparison between the manufacturing and service sectors. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terziovski, M. Innovation practice and its performance implications in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the manufacturing sector: A resource-based view. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, G.P.; Healey, M.P. Psychological Foundations of Dynamic Capabilities: Reflexion and Reflection in Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 1500–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmart, C. Innovative outreach increases adoption of sustainable winegrowing practices in Lodi region. Calif. Agric. 2008, 62, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.D. The quality of sustainability: Agroecological partnerships and the geographic branding of California winnegrapes. J. Rural Stud. 2007, 23, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. Exploratory study of climate change innovations in wine regions in Australia. Regional Studies 2016, 50, 1903–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammarra, A.; Biggiero, L. Heterogeneity and specificity of inter-firm knowledge flows in innovation networks. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 800–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. Technological and economic dynamics of the world wine industry: An introduction. Int. J. Technol. Glob. 2007, 3, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Van der Linde, C. Green and competitive: Ending the stalemate. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 72, 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Gerster, D.; Dremel, C.; Brenner, W.; Kelker, P. How enterprises adopt agile forms of organizational design: A multiple-case study. ACM SIGMIS Database DATABASE Adv. Inf. Syst. 2020, 51, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M. Ökologischer Weinbau: Positionierungsanalysen. Der Dtsch. Weinbau 2013, 5, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzdine-Chameeva, T.; Krzywoszynska, A. Barriers and driving forces in organic winemaking in Europe. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of the Association of Wine Business Research, Bordeaux, France, 9–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bernabéu, R.; Brugarolas, M.; Martínez-Carrasco, L.; Díaz, M. Wine origin and organic elaboration, differentiating strategies in traditional producing countries. Br. Food J. 2008, 110, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, T.; Newton, S.K. Environmental strategy: Does it lead to competitive advantage in the US wine industry? Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2012, 24, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daft, R. Organization Theory and Design; West: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Mignon, I.; Bankel, A. Sustainable business models and innovation strategies to realize them: A review of 87 empirical cases. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.; Geradts, T.H. Barriers and drivers to sustainable business model innovation: Organization design and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2020, 53, 101950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Pham, H.S.T.; Freeman, S. Dynamic capabilities in tourism businesses: Antecedents and outcomes. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Siller, L.; Matzler, K. The resource-based and the market-based approaches to cultural tourism in alpine destinations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 877–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peteraf, M.A. The Cornerstones of Competitive Advantage: A Resource-Based View. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Linares, R.; Kellermanns, F.W.; López-Fernández, M.C. Dynamic capabilities and SME performance: The moderating effect of market orientation. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 59, 162–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejardin, M.; Raposo, M.L.; Ferreira, J.J.; Fernandes, C.I.; Veiga, P.M.; Farinha, L. The impact of dynamic capabilities on SME performance during COVID-19. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C.G.G.; Patricia, G.; Hart, M.M. From initial idea to unique advantage: The entrepreneurial challenge of constructing a resource base. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2001, 15, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M. Innovation management of German wineries: From activity to capacity—An explorative multi-case survey. Wine Econ. Policy 2013, 2, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidakis, A.; Maclaran, P.; Bradshaw, A. Heterotopian space and the utopics of ethical and green consumption. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 494–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinney, T.M.; Auger, P.; Eckhardt, G.M. The Myth of the Ethical Consumer; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Budeanu, A. Sustainable tourist behaviour—A discussion of opportunities for change. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germov, J.; Freij, M. Portrayal of hte slow food movement in the Australian print media: Conviviality, localism and romanticism. J. Sociol. 2010, 47, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Jie, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, M. Green product innovation, green dynamic capability, and competitive advantage: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, S.; Rehman, S.U.; Alam, G.M.; Ashfaq, K.; Usman, M. Environmental MCS package, perceived environmental uncertainty and green performance: In green dynamic capabilities and investment in environmental management perspectives. Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 2022, 33, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Lyles, M.A.; Peteraf, M.A. Dynamic Capabilities: Current Debates and Future Directions. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, S1–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic Capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Oliveira, C. The influence of innovation in tangible and intangible resource allocation: A qualitative multi case study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressan, A.; Alonso, A.D.; Vu, O.T.K.; Do, L.T.H.; Martens, W. The role of tradition for food and wine producing firms in times of an unprecedented crisis. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 1170–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M. Strategic Grouping in a Fragmented Market. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2017, 32, 229–253. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, A.; Fiorentino, R.; Garzella, S. From the boundaries of management to the management of boundaries: Business processes, capabilities and negotiations. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2018, 25, 391–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.; Leih, S. Uncertainty, Innovation, and Dynamic Capabilities: An Introduction. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 58, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Stokes, N.M.S.B.P.P.; He, Q.; Duan, Y. Explicating dynamic capabilities for corporate sustainability. EuroMed J. Bus. 2013, 8, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.; Peteraf, M.; Leih, S. Dynamic Capabilities and Organizational Agility: Risk, Uncertainty and Strategy in the Innovation Economy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 58, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsato, R. Competitive Environmental Strategies: WHen Does It Pay to be Green. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2006, 48, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarhaus, T.; Liening, A. Building dynamic capabilities to cope with environmental uncertainty: The role of strategic foresight. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 155, 120033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, D.; Parker, R.; Pregelj, L.; Verreynne, M.-L. Deconstructing and reconstructing the capability hierarchy. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2013, 23, 1299–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M. Capabilities for Sustainable Business Success. Aust. J. Manag. 2004, 29, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouvrard, S.; Jasimuddin, S.M.; Spiga, A. Does sustainability push to reshape business models? Evidence from the European wine industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spender, J.-C. Making Knowledge the Basis of a Dynamic Theory of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. Specia Issue 1996, 17, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirzner, I. Competition and Entrepreneurship; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury, S.R.; Albinsson, P.A.; Shows, G.D. The winemaker as entrepreneurial marketer: An exploratory study. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2014, 26, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.K.; Daneke, G.A.; Lenox, M.J. Sustain. Dev. Entrep. Past Contrib. Future Dir. 2010, 25, 439–448. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Pullman, M.; Bouzdine-Chameeva, T.; Rodrigues, V.S. The role of the hub-firm in developing innovation capabilities: Considering the French wine industry cluster from a resource orchestration lens. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2022, 42, 526–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitelis, C.N.; Teece, D.J. Cross-border market co-creation, dynamic capabilities and the entrepreneuria theory of the multinational enterprise. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2010, 19, 1247–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, G.; Corinto, G.L. The Role of Women in the Sustainability of the Wine Indutry: Two Case Studies in Italy. In The Sustainability of Agro-Food and Natural Resource Systems in the Mediterranean Basin; Vastola, A., Ed.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; Dordreht, The Netherlands; London, UK, 2015; pp. 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hoemmen, G.; Altman, I.; Rendleman, M. Impact of sustainable viticulture programs on American Viticultural areas. J. Wine Res. 2015, 26, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, L.; Roehrdanz, P.R.; Ikegami, M.; Shepard, A.V.; Shaw, M.R.; Tabor, G.; Zhi, L.; Marquet, P.A.; Hijmans, R.J. Climate change, wine, and conservation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 6907–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, L.; Monßen, M. Kooperative Umweltpolitik und Nachhaltige Innovationen; Physica-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kooiman, J. Gooverning as Governance; SAGE: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.; Chen, Y. Organizational Attributes, Market Growth and Product Innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 6, 1312–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R. Millenial generation attitudes to sustainable wines: An exploratory study on Italian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabzdylova, B.; Raffensperger, J.F.; Castka, P. Sustainability in the New Zealand wine industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szolnoki, G. A cross-cultural comparison of sustainability in the wine industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunovic, I.; Jovanovic, V. Implementation of Sustainable Tourism in the German Alps: A Case Study. Sustainability 2017, 9, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J. Company learning about corporate social responsibility. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2005, 14, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Aleman, P.; Sandilands, M. Building value at the top and the bottom of the global supply chain: MNC-NGO partnerships. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2008, 51, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigon, A.; Doloreux, D.; Shearmur, R. Drivers of eco-innovation and conventional innovation in the Canadian wine industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 124115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenwald, G.C. A theory of multiple-case research. J. Personal. 1988, 56, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Giau, A.; Foss, N.J.; Furlan, A.; Vinelli, A. Sustainable development and dynamic capabilities in the fashion industry: A multi-case study. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedlich, S.; Kummer, B.; Bauer, M.; Rieckmann, M.; Bormann, I. Cultures of sustainability governance in higher education institutions: A multi-case study of dimensions and implications. High. Educ. Q. 2020, 74, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilinsky Jr, A.; Forbes, S.L.; Reed, M.M. Writing cases to advance wine business research and pedagogy: A Business Article by. Wine Econ. Policy 2016, 5, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Labaki, R.; Michael-Tsabari, N. Analyzing family business cases: Tools and techniques. Case Res. J. 2013, 33, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shortell, S.M.; Zajac, E.J. Perceptual and archival measures of Miles and Snow´s strategic types: A comprehensive assessment of reliability and validity. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 817–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, C.C.; Hrebiniak, L.G. Industry differences in environmental uncertainty and organizational characteristics related to uncertainty. Acad. Manag. J. 1980, 23, 750–759. [Google Scholar]

- Durán, W.F.; Aguado, D. CEOs’ managerial cognition and dynamic capabilities: A meta-analytical study from the microfoundations approach. J. Manag. Organ. 2022, 28, 451–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M. The entrepreneurship power house of ambition and innovation: Exploring German wineries. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2020, 41, 397–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-Maria, T.; Vermeulen, W.J.; Baumgartner, R.J. How do incumbent firms innovate their business models for the circular economy? Identifying micro-foundations of dynamic capabilities. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1308–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S. Simplifying Three-way Questionnaires-Do the Advantages of Binary Answer Categories Compensate for the Loss of Information? University of Wollongong: Hong Kong, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst, B.; Neale, M.C. Best practices for binary and ordinal data analyses. Behav. Genet. 2021, 51, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.M. Data visualization. In Data Science and Analytics; Kumari, S., Tripathy, K.K., Kumbhar, V., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2020; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Neely, A.; Hii, J. Innovation and business performance: A literature review; The Judge Institute of Management Studies University of Cambridge 15th Jan 1998; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 1998; pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.; Sroufe, R. Sustainability in the circular economy: Insights and dynamics of designing circular business models. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hina, M.; Chauhan, C.; Kaur, P.; Kraus, S.; Dhir, A. Drivers and barriers of circular economy business models: Where we are now, and where we are heading. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 333, 130049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehnem, S.; de Queiroz, A.A.F.S.; Pereira, S.C.F.; dos Santos Correia, G.; Kuzma, E. Circular economy and innovation: A look from the perspective of organizational capabilities. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, A.F.; Hubert, A.; Raineau, Y.; Franc, C.; Giraud-Héraud, É. Resistant grape varieties and market acceptance: An evaluation based on experimental economics. Oeno One 2018, 52, 247–263. [Google Scholar]

- Sarasvathy, S.D. Causation and Effectuation: Toward a Theoretical Shift from Economic Inevitability to Entrepreneurial Contingency. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servantie, V.; Rispal, M.H. Bricolage, effectuation, and causation shifts over time in the context of social entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2018, 30, 310–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommen, J.-P.; Boeker, W. Population Ecology Approach: Modelling Organizational Strategy as an Ecological Process. Die Unternehm. 1986, 40, 227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Sanchez, D.; Barton, J.; Bower, D. Implementing environmental management in SMEs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2003, 10, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.L. Consumer attitudes regarding environmentally sustainable wine: An exploratory study of the New Zealand marketplace. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosi, C.; Zanni, L. Moving from “typical products” to food related services—The slow food case as a new business paradigm. Br. Food J. 2004, 106, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovskaia, E. Sustainability criteria: Their indicators, control, and monitoring (with examples from the biofuel sector). Environ. Sci. Eur. 2014, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, L.; Levang, P.; Ghazoul, J. Designer landscapes for sustainable biofuels. Trends Ecol Evol 2009, 24, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti Barros Rodrigues, B.; Gohr, C.F. Dynamic capabilities and critical factors for boosting sustainability-oriented innovation: Systematic literature review and a framework proposal. Eng. Manag. J. 2022, 34, 591–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 25, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Grant, L.E. Eco-Labeling Strategies and Price-Premium: The Wine Industry Puzzle. Bus. Soc. 2014, 53, 6–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kump, B.; Schweiger, C. Mere adaptability or dynamic capabilities? A qualitative multi-case study on how SMEs renew their resource bases. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2022, 14, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacht, D.; Stephan, U.; Gorgievski, M. More than money: Developing an integrative multi-factorial measure of entrepreneurial success. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2016, 34, 1098–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorich, D.; Rivera, M. The Relationship between Motivation and Owner-Operated Small Business Firm Success. In Proceedings of the 2018 Engaged Management Scholarship Conference, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 6–9 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saunila, M. Innovation capability for SME success: Perspectives of financial and operational performance. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2014, 11, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.; Padmore, J.; Newman, N. Towards a new model of success and performance in SMEs. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2012, 18, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, C.; Cavicchi, A.; Gilinsky, A.; Newton, S.; Rabino, S. Niche Strategy and Resources: Dilemmas and open questions, an exploratory study. In Proceedings of the Academy of Wine Business Research, 8th International Conference, Geisenheim, Germany, 28–30 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maruso, L.C.; Weinzimmer, L.G. A normative framework to assess small-firm entry strategies: A resource-based view. J. Small Bus. Strategy 1999, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J.; Wright, L.T. A qualitative research agenda for small to medium-sized enterprises. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2001, 19, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, D.; Lozano, J.M. SMEs and CSR: An approach to CSR in their own words. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, A.; Cummins, D. The use of qualitative methods to research networking in SMEs. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 1999, 2, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simba, A.; Ojong, N. Engaged scholarship: Encouraging interactionism in entrepreneurship and small-to-medium enterprise (SME) research. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2017, 24, 1009–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A. Sustainability experiences in the wine setor: Toward the development of an international indicators system. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 172, 3791–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.; Vastola, A. Sustainable winegrowing: Current perspectives. Int. J. Wine Res. 2015, 7, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Generic Strategy | Quality Leader | Price–Value Leadership | Premium Strategy | Niche Player |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership | Cooperative | State-owned | Family-owned | Family-owned |

| Size (hectares vineyard) | 866 | 22 | 25 | 14 |

| Value chain coverage | Joint production and sales; individual production | Full coverage plus research institution | Full coverage | Full coverage |

| Specific characteristics | Rich portfolio of brands; professional sales/CRM | Previous awards for the wines; minimal marketing | Organic and biodynamic certification | Strong growth; CRM and balanced scorecard |

| Dynamic Capabilities for Social Sustainability | Dynamic Capabilities for Economic Sustainability | Dynamic Capabilities for Ecologic Sustainability |

|---|---|---|

| Positive working climate (6 routines) | Company strategy (6 routines) | Water (5 routines) |

| Communication inside organization (5 routines) | Key financial data (4 routines) | Energy (5 routines) |

| Fair pay and equality (6 routines) | Secured successor (7 routines) | Soil and biodiversity (8 routines) |

| Training and education (5 routines) | Safeguarding against risks (5 routines) | Waste and materials (5 routines) |

| Social and regional engagement (6 routines) | Future viability (4 routines) | CO2 emissions (4 routines) |

| Sustainable suppliers and partners (4 routines) | Fungus-resistant varieties (2 routines) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dressler, M. Sustainable Business Model Design: A Multi-Case Approach Exploring Generic Strategies and Dynamic Capabilities on the Example of German Wine Estates. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15053880

Dressler M. Sustainable Business Model Design: A Multi-Case Approach Exploring Generic Strategies and Dynamic Capabilities on the Example of German Wine Estates. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15053880

Chicago/Turabian StyleDressler, Marc. 2023. "Sustainable Business Model Design: A Multi-Case Approach Exploring Generic Strategies and Dynamic Capabilities on the Example of German Wine Estates" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15053880

APA StyleDressler, M. (2023). Sustainable Business Model Design: A Multi-Case Approach Exploring Generic Strategies and Dynamic Capabilities on the Example of German Wine Estates. Sustainability, 15(5), 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15053880