Inherited Patience and the Taste for Environmental Quality

Abstract

:1. Introduction

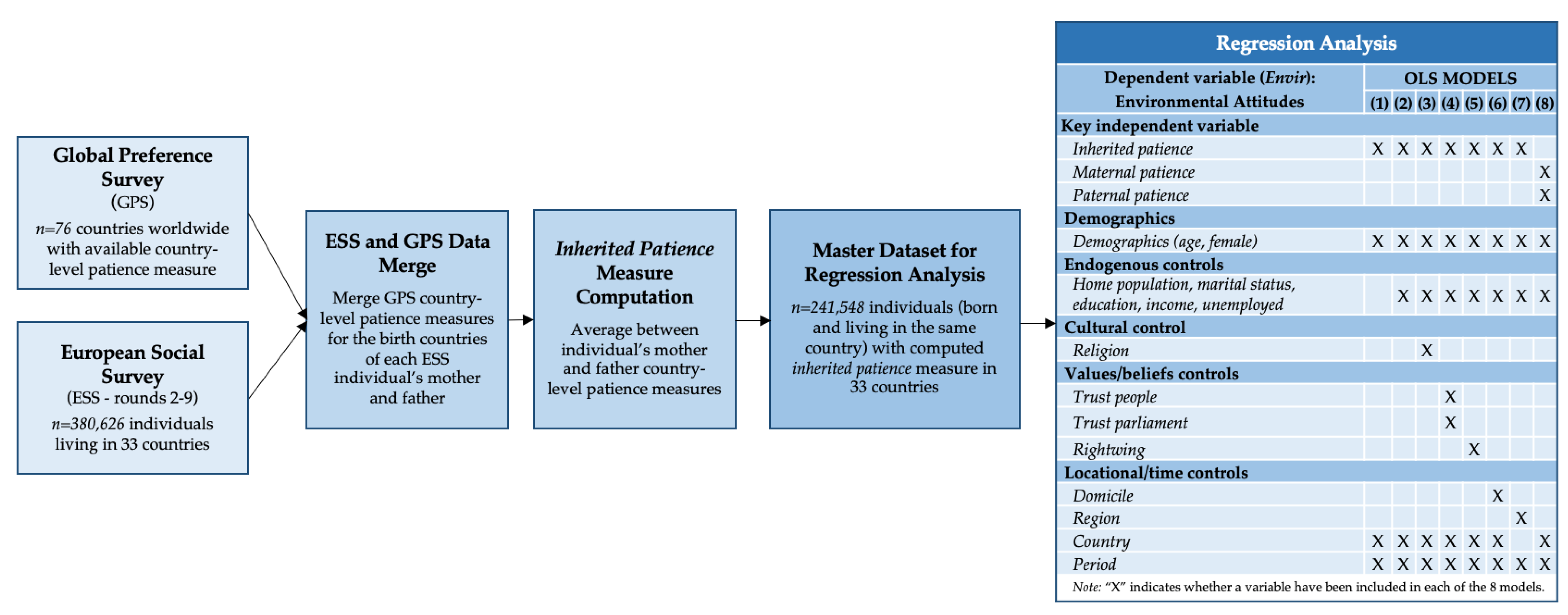

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolf, M.J.; Emerson, J.W.; Esty, D.C.; de Sherbinin, A.; Wendling, Z.A. Environmental Performance Index; Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy: New Haven, CT, USA, 2022; Available online: epi.yale.edu (accessed on 18 December 2017).

- Groosman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Economic Growth and the Environment. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jayadevappa, R.; Chhatre, S. International trade and environmental quality: A survey. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzin, Y.H.; Bond, C.A. Democracy and environmental quality. J. Dev. Econ. 2006, 81, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitenzorgy, M.; Mol, A.P.J. Does Democracy Lead to a Better Environment? Deforestation and the Democratic Transition Peak. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2011, 48, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, P.; Muthukrishnan, S. Green consumerism and pollution control. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2015, 114, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwinska, K.; Kampas, A.; Longhurst, K. Interactions between Democracy and Environmental Quality: Towards a More Nuanced Understanding. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, D.; Ozturk, I.; Ullah, S. Institutional factors-environmental quality nexus in BRICS: A strategic pillar of governmental performance. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 5777–5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kountouris, Y.; Remoundou, K. Cultural influence on Preferences and Attitudes for Environmental Quality. Kyklos 2016, 69, 369–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, A.; Becker, A.; Dohmen, T.; Enke, B.; Huffman, D.; Sunde, U. Global evidence on economic preferences. Q. J. Econ. 2018, 133, 1645–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guiso, L.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. Does Culture Affect Economic Outcomes? J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández, R. Does culture matter? In Handbook of Social Economics, 1st ed.; North Holland Publisher: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 481–510. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.K. The effect of language on economic behavior: Evidence from savings rates, health behaviors, and retirement assets. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 690–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mavisakalyan, A.; Tarverdi, Y.; Weber, C. Talking in the present, caring for the future: Language and environment. J. Comp. Econ. 2018, 46, 1370–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cai, M.; Murtazashvili, I.; Murtazashvili, J.B.; Salahodjaev, R. Patience and climate change mitigation: Global evidence. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuhrmann-Riebel, H.; D’Exelle, B.; Verschoor, A. The role of preferences for pro-environmental behaviour among urban middle class households in Peru. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 180, 106850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, R.G.; Siikamäki, J. Individual Time Preferences and Energy Efficiency. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerst, F.; Ramandeep, S. How present bias forestalls energy efficiency upgrades: A study of household appliance purchases in India. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lades, L.K.; Laffan, K.; Weber, T.O. Do economic preferences predict pro- environmental behaviour? Ecol. Econ. 2021, 183, 106977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökmen, A. The effect of gender on environmental attitude: A meta-analysis study. J. Pedagog. Res. 2021, 5, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Evans, G.W.; Moon, M.J.; Kaiser, F.G. The development of children’s environmental attitude and behavior. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 58, 101947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsson, J.; Lundqvist, L.J.; Sundström, A. Energy saving in Swedish households. the (relative) importance of environmental attitudes. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 5182–5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Teng, M.; Han, C. How does environmental knowledge translate into pro-environmental behaviors?: The mediating role of environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heal, G. The economics of the climate. J. Econ. Lit. 2017, 55, 1046–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arbuckle, M.B.; Konisky, D.M. The role of religion in environmental attitudes. Soc. Sci. Q. 2015, 96, 1244–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konisky, D.M. The greening of Christianity? A study of environmental attitudes over time. Environ. Politics 2018, 27, 267–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, M.; Vannoorenberghe, G. Patience and long-run growth. Econ. Lett. 2015, 137, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Godoy, R.; Byron, E.; Reyes-García, V.; Leonard, W.R.; Patel, K.; Apaza, L.; Pérez, E.; Vadez, V.; Wilki, D. Patience in a foraging-horticultural society: A test of competing hypotheses. J. Anthropol. Res. 2004, 60, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doepke, M.; Zilibotti, F. Culture, entrepreneurship, and Growth. In Handbook of Economic Growth; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, G. Discounting for personal and social payments: Patience for others, impatience for ourselves. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2013, 66, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stango, V.; Zinman, J. We Are All Behavioral, More or Less: A Taxonomy of Consumer Decision Making; NBER Working Paper Series; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; p. 28138. [Google Scholar]

- Galor, O.; Özak, Ö. The Agricultural Origins of Time Preference; CESifo Working Paper Series; CESifo?: Munich, Germany, 2015; p. 5211. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, A.; Becker, A.; Dohmen, T.; Huffman, D.; Sunde, U. The Preference Survey Module: A Validated Instrument for Measuring Risk, Time, and Social Preferences; IZA Discussion Paper Series; IZA Institute of Labor Economics: Bonn, Germany, 2016; p. 9674. [Google Scholar]

- Acock, A.C.; Bengtson, V.L. On the Relative Influence of Mothers and Fathers: A Covariance Analysis of Political and Religious Socialization. J. Marriage Fam. 1978, 40, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Silverstein, M.; Lendon, J.P. Intergenerational transmission of values over the family life course. Adv. Life Course Res. 2012, 17, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.; Chan, H. Generalized trust narrows the gap between environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior: Multilevel evidence. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 48, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, H.; Marshall, G.A. Trust, political orientation, and environmental behavior. Environ. Politics 2018, 27, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | Observation | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||||

| Envir | Measure of individual environmental attitudes on an increasing scale in the taste for environmental quality, from 1 to 6 | 241,548 | 4.878 | 1.035 | 1 | 6 |

| Key independent variable | ||||||

| Inherited patience | Measure of individual-level of patience calculated as the average between maternal- and paternal-patience measures | 241,548 | 0.266 | 0.411 | −0.606 | 1.071 |

| Maternal patience | Country-level-patience measure for mother’s country of origin | 241,548 | 0.267 | 0.414 | −0.606 | 1.071 |

| Paternal patience | Country-level-patience measure for father’s country of origin | 241,548 | 0.265 | 0.414 | −0.606 | 1.071 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age | Age | 240,875 | 48.446 | 18.769 | 14 | 105 |

| Female | Gender: 0 = Male, 1 = Female | 241,548 | 0.543 | 0.498 | 0 | 1 |

| Endogenous controls | ||||||

| Home population | Number of people living regularly in household | 241,313 | 2.658 | 1.406 | 1 | 22 |

| Marital status | Marital status: 1 = Married, 2 = Separated, 3 = Divorced, 4 = Widow, 5 = Never married | 234,999 | 2.675 | 1.786 | 1 | 5 |

| Education | Years of education completed | 239,105 | 12.249 | 4.091 | 0 | 60 |

| Income | Total household net income (after tax and compulsory deductions) by decile | 183,008 | 5.427 | 2.748 | 1 | 10 |

| Unemployed | Ever unemployed for more than 3 months: 0 = No, 1 = Yes | 241,548 | 0.264 | 0.441 | 0 | 1 |

| Cultural control | ||||||

| Religion | Religion affiliation: 0 = None, 1 = Catholic, 2 = Protestant, 3 = Orthodox, 4 = Other Christian, 5 = Other religion | 234,377 | 1.116 | 1.349 | 0 | 5 |

| Values/beliefs controls | ||||||

| Trust people | Trust in people on a scale from 0 = You can’t be too careful to 10 = Most people can be trusted | 240,801 | 4.950 | 2.426 | 0 | 10 |

| Trust parliament | Trust in country’s parliament on a scale from 0 = No trust at all to 10 = Complete trust | 235,826 | 4.248 | 2.590 | 0 | 10 |

| Right-wing | Self-placement on political views on a left–right scale from 0 = Left to 10 = Right | 207,362 | 5.149 | 2.213 | 0 | 10 |

| Locational/time controls | ||||||

| Domicile | Type of living area: 1 = Big city, 2 = Suburb, 3 = Town, 4 = Village, 5 = Countryside | 241,084 | 2.849 | 1.207 | 1 | 5 |

| Region | Subnational-EU region of residence | 150,930 | 216.520 | 125.757 | 1 | 443 |

| Country | Country of residence | 241,548 | 15.981 | 9.013 | 1 | 33 |

| Period | ESS round | 241,548 | 5.466 | 2.254 | 2 | 9 |

| Envir | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inherited patience | 0.0883 *** | 0.0788 *** | 0.106 *** | 0.0668 *** | 0.0748 *** | 0.0739 *** | 0.0987 *** | |

| (4.334) | (3.390) | (4.440) | (2.849) | (3.140) | (3.173) | (3.595) | ||

| Maternal patience | 0.0457 * | |||||||

| (1.805) | ||||||||

| Paternal patience | 0.0335 | |||||||

| (1.387) | ||||||||

| Age | 0.00659 *** | 0.00881 *** | 0.00859 *** | 0.00875 *** | 0.00902 *** | 0.00878 *** | 0.00884 *** | 0.00881 *** |

| (59.03) | (45.21) | (43.23) | (44.51) | (43.91) | (45.02) | (36.81) | (45.21) | |

| Female | 0.0941 *** | 0.101 *** | 0.0979 *** | 0.103 *** | 0.100 *** | 0.102 *** | 0.110 *** | 0.101 *** |

| (22.65) | (20.68) | (19.69) | (20.88) | (19.59) | (20.79) | (18.23) | (20.68) | |

| Endogenous Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| Religion FE | YES | |||||||

| Trust people | 0.0130 *** | |||||||

| (11.60) | ||||||||

| Trust parliament | 0.00233 ** | |||||||

| (2.203) | ||||||||

| Rightwing | −0.0219 *** | |||||||

| (−18.95) | ||||||||

| Domicile FE | YES | |||||||

| Regional FE | YES | |||||||

| Country FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| Period FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | 4.464 *** | 4.181 *** | 4.139 *** | 4.133 *** | 4.304 *** | 4.181 *** | 5.034 *** | 4.181 *** |

| (256.8) | (158.1) | (150.9) | (152.4) | (153.0) | (155.2) | (7.179) | (158.0) | |

| Observations | 240,875 | 176,326 | 171,598 | 172,880 | 156,803 | 176,079 | 115,001 | 176,326 |

| R-squared | 0.044 | 0.053 | 0.054 | 0.054 | 0.055 | 0.053 | 0.072 | 0.053 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davis, L.; Garrido, D.; Missura, C. Inherited Patience and the Taste for Environmental Quality. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4038. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054038

Davis L, Garrido D, Missura C. Inherited Patience and the Taste for Environmental Quality. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4038. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054038

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavis, Lewis, Dolores Garrido, and Carolina Missura. 2023. "Inherited Patience and the Taste for Environmental Quality" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4038. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054038