Smartphones as a Platform for Tourism Management Dynamics during Pandemics: A Case Study of the Shiraz Metropolis, Iran

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism Management Dynamics and Smartphones during COVID-19

2.2. Smartphone Trends in Tourism Management and Tourist Behavior

2.3. Tourism Postmodern Organizations and Turbulent Times

3. Materials and Methods

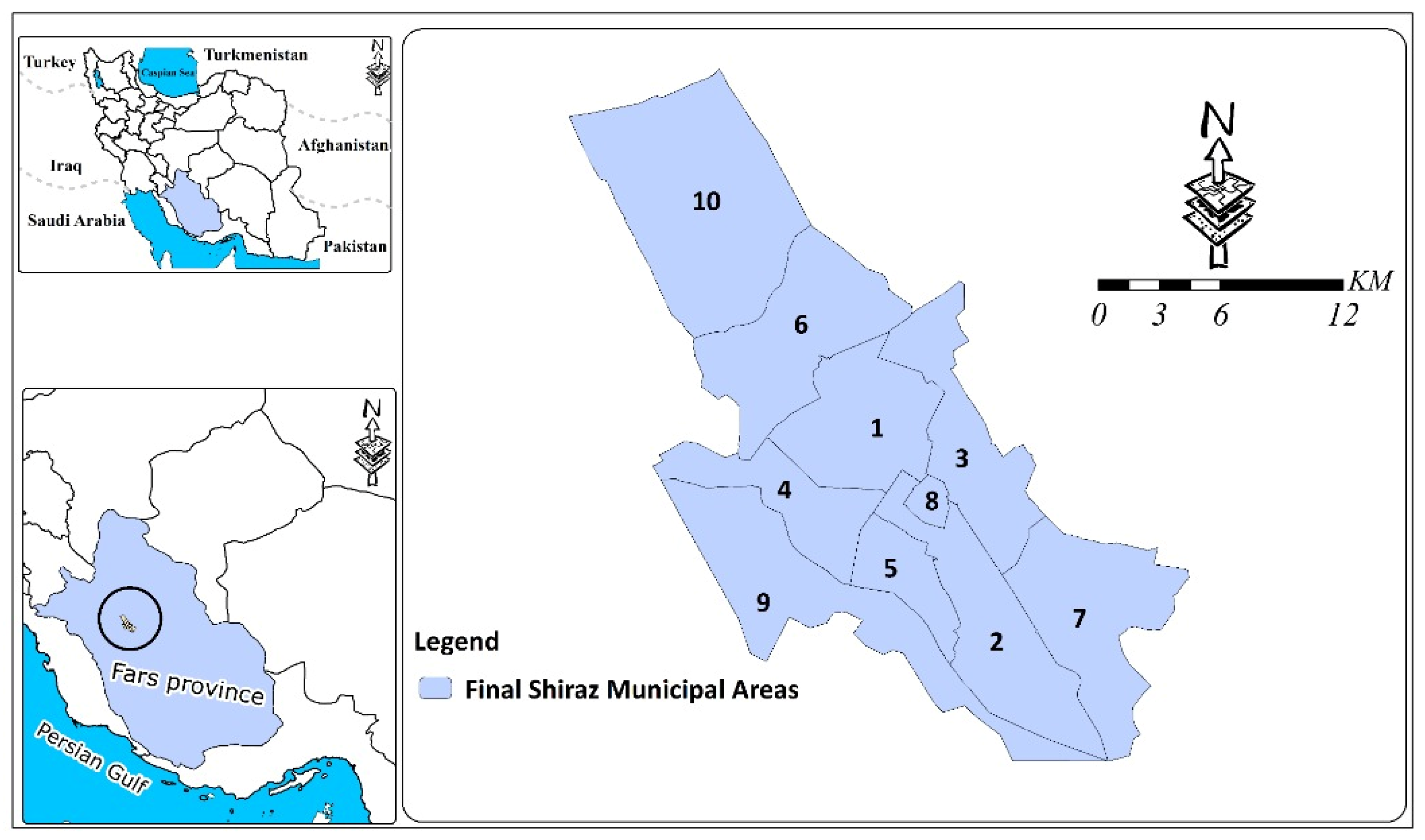

3.1. Study Site

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Data Analysis

Final Model Design Based on the Findings

5. Results

5.1. Smartphones as Part of Postmodern Tourism Organization and Tourism Management Dynamics

“COVID-19 has prevented tourists from traveling to Shiraz. In turn, it has disrupted tourism-related businesses. Starting a virtual trip and sharing clips from Shiraz can relaunch the relevant businesses and ensure the health of tourists.”

“As the mayor of Shiraz explicitly stated during the COVID-19 pandemic, “empathy and unity should be the priority of Shiraz tourism authorities,” and, on the other hand, during quarantine, the feelings of empathy, cooperation, and mental health of tourists decreased. In my opinion, by creating Shiraz websites and virtual tours, we can improve the damage.”

“I have traveled a lot to Iran; most of my trips have been to Shiraz. My trip to Shiraz was due to my best friends, whom I found through social media, especially Instagram. Before starting COVID-19, I traveled to Iran every summer. Now my friends who live in Shiraz always send me photos and videos of Hafez and Sa’adi. The last time I saw Shiraz on a virtual trip was through a video call. My smartphone gave me by my friends. Our relationship has become much more intimate due to quarantine conditions and travel rules. My smartphone played a key role in the formation of these friendships, and in this situation, I needed to communicate with them mentally. Thank you, my smart friend.”

5.2. Psychological Recovery

“I am an Iranian, and I live with my family in Europe. I recently visited the Louvre Museum in Paris. I started my visit due to my dependence on Iran and the Iranian collections that are in Level 0 and section 308 of the museum. During the visit, I felt very homesick, and my trip to Fars was associated with me. I quickly searched for the cultural and historical places and the tomb of the Persian-speaking poets of Shiraz on my smartphone. It was like a virtual journey for me that made me feel good and lessened my nostalgia.”

5.3. Smartphone Marketing

“Social media platforms in times of crisis are the best way to offer tourist attractions. In this case, a robust database is provided for tourists who can check it at any time using their phones. In this way, tourists can also publish their experiences and strengthen their empathy and mental health by reviewing memories.”

“By creating various tourism applications in Shiraz, the tourism capabilities of the city can be provided in detail in different languages. In recent years, the Tourism Organization has launched the virtual tourism portal of Shiraz with the use of panoramic images and virtual tours, videos, photos, maps, and descriptions (visit www.fafarschto.ir (accessed on 25 June 2022)).”

“Recently, joint meetings of Iranian and European tour operators, especially Hungarian ones, have been held with the help of Shiraz Municipality. There are very close ethnic, cultural, and racial commonalities between the Iranian people and the tribes living in the Hungarian city of Jászberény. Many of them want to travel to Shiraz. As a tourist in Hungary, I have always tried to show them the potential of tourism through the websites available for virtual tourism in Fars and Shiraz provinces. In my opinion, smartphones can be very effective as a tool for marketing tourism compatible during a pandemic in Shiraz.” (Figure 4).

5.4. Travel Planning

“After essential travel items, such as passports, the smartphone ranks first in “what to take with you on the trip.” The last thing I had before going to bed was always a mobile phone so that I could make the next day’s travel plans. During the trip, the most common use of smartphones was to take photos, post them on Instagram and WhatsApp, and then use the map. Many large digital companies, such as Google, Facebook, and National Geographic, have a section called travel. In my opinion, applications such as MyShiraz or Shiraz travel can be suggested for planning a trip to Shiraz.”

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ntounis, N.; Parker, C.; Skinner, H.; Steadman, C.; Warnaby, G. Tourism and Hospitality industry resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from England. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosazadeh, H.; Razi, F.F.; Lajevardi, M.; Mousazadeh, H.; Ghorbani, A.; Almani, F.A.; Shiran, F. Restarting Medical Tourism in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Strategic-based Approach. J. Health Rep. Technol. 2021, 8, e117932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Danaei, A.; Zargar, S.M.; Hematian, H. Designing of smart tourism organization (STO) for tourism management: A case study of tourism organizations of South Khorasan province, Iran. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- García-Milon, A.; Olarte-Pascual, C.; Juaneda-Ayensa, E. Assessing the moderating effect of COVID-19 on intention to use smartphones on the tourist shopping journey. Tour. Manag. 2021, 87, 104361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, H. Place Branding—The Challenges of Getting It Right: Coping with Success and Rebuilding from Crises. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 2, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analytica, O. Costa Rica’s economy looks set for a strong recovery. Emerald Expert Brief. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawara, K.; Kamata, H.; Chubachi, S.; Namkoong, H.; Tanaka, H.; Lee, H.; Otake, S.; Fukushima, T.; Kusumoto, T.; Morita, A.; et al. Diagnostic significance of secondary bacteremia in patients with COVID-19. J. Infect. Chemother. 2023; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N. Post-pandemic marketing: When the peripheral becomes the core. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomski, P. COVID-19: From temporary de-globalisation to a re-discovery of tourism? Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Danaei, A.; Barzegar, S.M.; Hemmatian, H. Post modernism and designing smart tourism organization (STO) for tourism management. J. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 8, 50–69. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Cai, W. Understanding the smartphone usage of Chinese outbound tourists in their shopping practices. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 2955–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Mousazadeh, H.; Taheri, F.; Ehteshammajd, S.; Azadi, H.; Yazdanpanah, M.; Khajehshahkohi, A.; Tanaskovik, V.; Van Passel, S. An attempt to develop ecotourism in an unknown area: The case of Nehbandan County, South Khorasan Province, Iran. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 11792–11817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarchi, M.K.R.; Jabbari, A.; Hatam, N.; Bastani, P.; Shafaghat, T.; Fazelzadeh, O. Strategic Analysis of Shiraz Medical Tourism Industry: A Mixed Method Study. Galen Med. J. 2018, 7, e1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Kock, F. The coronavirus pandemic—A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giddy, J.K.; Rogerson, C.M.; Rogerson, J.M. Rural Tourism Firms in the COVID-19 Environment: South African Challenges. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2022, 41, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Driha, O.M.; Sinha, A. The dynamic effects of globalization process in analysing N-shaped tourism led growth hypothesis. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Costa, C. (Eds.) Tourism Management Dynamics: Trends, Management and Tools; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Raheem, B.; Mahmood, M.D.; Abu Taher, G.; Shakeel, Z. A Study on The Use of Smartphone Applications in English Language Learning with Special Reference to COVID-19 Pandemic. J. La Edusci 2022, 3, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopdar, P.K.; Paul, J.; Prodanova, J. Mobile shoppers’ response to COVID-19 phobia, pessimism and smartphone addiction: Does social influence matter? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 174, 121249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Warrier, L.; Bolia, B.; Mehta, S. Past, present, and future of virtual tourism-a literature review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, M.J. Organization Theory: Modern, Symbolic, and Postmodern Perspectives; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mengistu, N.; Habtamu, E.; Kassaw, C.; Madoro, D.; Molla, W.; Wudneh, A.; Abebe, L.; Duko, B. Problematic smartphone and social media use among undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic: In the case of southern Ethiopia universities. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nankervis, A.R.; Cameron, R. Capabilities and competencies for digitised human resource management: Perspectives from Australian HR professionals. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2023, 61, 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Alawi, A.I.; Messaadia, M.; Mehrotra, A.; Sanosi, S.K.; Elias, H.; Althawadi, A.H. Digital transformation adoption in human resources management during COVID-19. Arab. Gulf J. Sci. Res. 2023; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, D.C.; Bran, F. The use of smartphone for the search of touristic information. An application of the theory of planned behavior. Econ. Comput. Econ. Cybern. Stud. Res. 2020, 54, 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Z.; Magnini, V.P.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Information technology and consumer behavior in travel and tourism: Insights from travel planning using the internet. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 22, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-S.; Li, H.-T.; Li, C.-R.; Zhang, D.-Z. Factors affecting hotels’ adoption of mobile reservation systems: A technology-organization-environment framework. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.W.-H.; Lee, V.H.; Lin, B.; Ooi, K.-B. Mobile applications in tourism: The future of the tourism industry? Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 560–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, F.; Sultan, M.; Badulescu, D.; Badulescu, A.; Borma, A.; Li, B. Sustainable Destination Marketing Ecosystem through Smartphone-Based Social Media: The Consumers’ Acceptance Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.E.; Ghali, K.; Cherrett, T.; Speed, C.; Davies, N.; Norgate, S. Tourism and the smartphone app: Capabilities, emerging practice and scope in the travel domain. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Jodice, L.W.; Norman, W.C. How do tourists search for tourism information via smartphone before and during their trip? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 45, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Number of Smartphone Subscriptions Worldwide from 2016 to 2027. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-of-smartphone-users-worldwide/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Kah, J.A.; Lee, S.-H. A new approach to travel information sources and travel behaviour based on cognitive dissonance theory. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 19, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lehto, X.Y.; Morrison, A.M.; Jang, S. Structure of Travel Planning Processes and Information Use Patterns. J. Travel Res. 2011, 51, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Koo, C.; Kim, J.K. Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation for using a booth recommender system service on exhibition attendees’ unplanned visit behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Eves, A.; Stienmetz, J. The Impact of Social Media Use on Consumers’ Restaurant Consumption Experiences: A Qualitative Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xiang, Z.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Smartphone Use in Everyday Life and Travel. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, F. Mobile recommender systems. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2010, 12, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fong, L.H.N.; Law, R.; Ye, B.H. Outlook of tourism recovery amid an epidemic: Importance of outbreak control by the government. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 86, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Tourist Arrivals down 87% in January 2021 as Unwto Calls for Stronger Coordination to Restart Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/tourist-arrivals-down-87-in-january-2021-as-unwto-calls-for-stronger-coordination-to-restart-tourism (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Kwok, A.O.J.; Koh, S.G.M. COVID-19 and Extended Reality (XR). Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1935–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sañudo, B.; Fennell, C.; Sánchez-Oliver, A.J. Objectively-assessed physical activity, sedentary behavior, smartphone use, and sleep patterns pre-and during-COVID-19 quarantine in young adults from Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, H. The Role of Emotional Factors in Developing Consumer and Brand Relations in the Medical Tourism Industry. Case Study: Hospitals of Shiraz City. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2020, 11, 1893–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Molavi Vardanjani, H.; Salehi, Z.; Alembizar, F.; Cramer, H.; Pasalar, M. Prevalence and the Determinants of Traditional, Complementary, and Integrative Medicine Use Among Breastfeeding Mothers: A Cross-section Study. J. Integr. Complement. Med. 2022, 28, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk-Anioł, J.; Grochowicz, M.; Pawlusiński, R. How a Tourism City Responds to COVID-19: A CEE Perspective (Kraków Case Study). Sustainability 2021, 13, 7914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapointe, D. Reconnecting tourism after COVID-19: The paradox of alterity in tourism areas. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejón-Guardia, F.; Polo-Peña, A.I.; Maraver-Tarifa, G. The acceptance of a personal learning environment based on Google apps: The role of subjective norms and social image. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2020, 32, 203–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Guerreiro, J.; Ali, F. 20 years of research on virtual reality and augmented reality in tourism context: A text-mining approach. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogicevic, V.; Seo, S.; Kandampully, J.A.; Liu, S.Q.; Rudd, N.A. Virtual reality presence as a preamble of tourism experience: The role of mental imagery. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, M.; Velikova, N.; Dodd, T.; Blankenship, T. Generational differences in risk perception and situational uses of wine information sources. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2019, 32, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Gretzel, U. On-site decision-making in smartphone-mediated contexts. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamsfus, C.; Wang, D.; Alzua-Sorzabal, A.; Xiang, Z. Going mobile: Defining context for on-the-go travelers. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Torrico, P.; Prodanova, J.; San-Martín, S.; Jimenez, N. The ideal companion: The role of mobile phone attachment in travel purchase intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1659–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, G.; Scarinci, J. Consumers’ Use of Smartphone Technology for Travel and Tourism in a COVID Era: A Scoping Review. J. Resilient Econ. 2022, 2, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Travel risk perception and travel behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokni, L. The Psychological Consequences of COVID-19 Pandemic in Tourism Sector: A Systematic Review. Iran. J. Public Health 2021, 50, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, J.; Yuan, G.; Yoo, C. The effect of the perceived risk on the adoption of the sharing economy in the tourism industry: The case of Airbnb. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebeccaa, P.; Giampaolob, V.; Laurac, G.; Danieled, D. When empathy prevents negative reviewing behavio. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 265–278. [Google Scholar]

- Brouder, P. Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Suskewicz, J. Does Your Company Have a Long-Term Plan for Remote Work. 2020. Available online: https://hbr.org/2020/07/does-your-company-have-a-long-term-plan-for-remote-work (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Hall, M.C.; Prayag, G.; Fieger, P.; Dyason, D. Beyond panic buying: Consumption displacement and COVID-19. J. Serv. Manag. 2020, 32, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.G.; Dang, A. Creating “Smart” Policy to Promote Entrepreneurship and Innovation. In The Role of Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Economic Growth; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kar, N.S.; Basu, A.; Kundu, M.; Giri, A. Urban heritage tourism in Chandernagore, India: Revival of shared Indo-French Legacy. Geojournal 2020, 87, 1575–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Bouey, J. Public mental health crisis during COVID-19 pandemic, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Choi, J.J.; Pinheiro, L.C.; Schenck, E.J.; Chen, R.; Jabri, A.; Satlin, M.J.; Campion, T.R., Jr.; Nahid, M.; Ringel, J.B. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in New York city. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2372–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.S.; Chee, C.Y.; Ho, R.C. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2020, 49, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, J. Restaurants Will Never Be the Same after Coronavirus–But That May Be a Good Thing. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/14/coronavirus-restaurants-pandemic-workers-communities-prices (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Tourism from Zero. Tourism From Zero Initiative. Available online: https://tourismfromzero.org (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Nepal, S.K. Adventure travel and tourism after COVID-19–business as usual or opportunity to reset? Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Xiao, X.; Xu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y. The potential of virtual tourism in the recovery of tourism industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, R.; Mostofa, M.G.; Khondker, T.W. Mobile technology uses towards marketing of tourist destinations: An analysis from therapeutic point of view. J. Mob. Comput. Appl. 2019, 6, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.H.; Sun, S.; Law, R. Value proposition of smartphone destination marketing: The cases of Hong Kong and South Korea. J. Econ. Manag. 2022, 44, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunfio, M.; Pasquinelli, C. Smart technologies in the COVID-19 crisis: Managing tourism flows and shaping visitors’ behaviour. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 29, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A. COVID-19 crisis: A new model of tourism governance for a new time. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2020, 12, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilembwe, J.M.; Gondwe, F.W. Role of Social Media in Travel Planning and Tourism Destination Decision Making. In Handbook of Research on Social Media Applications for the Tourism and Hospitality Sector; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 36–51. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Mehraliyev, F.; Liu, C.; Schuckert, M. The roles of social media in tourists’ choices of travel components. Tour. Stud. 2020, 20, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Yoo, M. The role of social media during the pre-purchasing stage. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2016, 7, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priatmoko, S.; Kabil, M.; Purwoko, Y.; Dávid, L. Rethinking Sustainable Community-Based Tourism: A Villager’s Point of View and Case Study in Pampang Village, Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, A.; Croy, G.; Mair, J. Social Media in Destination Choice: Distinctive Electronic Word-of-Mouth Dimensions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, L.; Di Virgilio, F.; Pantano, E. Social network for the choice of tourist destination: Attitude and behavioural intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2012, 1, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.; Jang, S. Restaurant experiences triggering positive electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) motivations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkono, M. A netnographic examination of constructive authenticity in Victoria Falls tourist (restaurant) experiences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, K.; Raj, S. The trustworthiness of travel and tourism information sources of social media: Perspectives of international tourists visiting Ethiopia. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabil, M.; Priatmoko, S.; Magda, R.; Dávid, L. Blue Economy and Coastal Tourism: A Comprehensive Visualization Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Popp, J.; Talib, M.N.A.; Lakner, Z.; Khan, M.A.; Oláh, J. Asymmetric Impact of Institutional Quality on Tourism Inflows Among Selected Asian Pacific Countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alreahi, M.; Bujdosó, Z.; Kabil, M.; Akaak, A.; Benkó, K.F.; Setioningtyas, W.P.; Dávid, L.D. Green Human Resources Management in the Hotel Industry: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, É.M.S.; Bergstad, C.J.; Nässén, J. Understanding daily car use: Driving habits, motives, attitudes, and norms across trip purposes. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 68, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhu, K.; Kang, L.; Dávid, L.D. Tea Culture Tourism Perception: A Study on the Harmony of Importance and Performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| R | Group A | Number | Participant as Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Smartphone users in destination management organizations | P1 | User in a five-star hotel |

| P2 | |||

| P3 | |||

| P4 | User in a travel agency | ||

| P5 | |||

| P6 | |||

| P7 | |||

| P8 | |||

| P9 | |||

| P10 | |||

| P11 | |||

| P12 | |||

| P13 | |||

| P14 | |||

| P15 | User in a four-star hotel | ||

| P16 | |||

| R | Group B | Tourists | |

| 2 | Bloggers | 16 | Travel bloggers during the pandemic |

| Total | 32 | ||

| Themes | Subthemes | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Tourism management dynamics during pandemics | Identify trends early, Design proactive strategies | 24 |

| Identify potential opportunities from changes and threats | 23 | |

| Continuation of tourism businesses during the pandemic | 22 | |

| Adjusting human resources and the emergence of new tourism businesses | 20 | |

| Psychological impacts | Expanding the network of tourist friends | 21 |

| Increasing the resilience of tourists locked up at home | 22 | |

| Changing preferences of tourists during the pandemic | 24 | |

| Smartphone marketing | Perceived ease of use of smartphones in marketing tourist sites | 21 |

| The tourist is more exposed to marketing activities | 20 | |

| Smartphones are available to tourists anytime and anywhere to promote marketing activities | 19 | |

| In smartphone marketing, the tourist can quickly connect with the source of the message (hotel, travel agency, fast food services, etc.) | 22 | |

| Travel planning | Familiarity with different potentials of tourism in the destination and new entertainment | 23 |

| Better choice of travel destination by watching high-quality videos and images, and acquiring more information through social media | 21 | |

| Communication with tourism service providers at the destinations | 22 | |

| Make payments, reservations, and other things before traveling | 19 | |

| Postmodern organization | 24 | |

| Breaking the concept of organization as a physical space | 23 | |

| Virtual organization is the second dimension of physical organization | 22 | |

| Adjustment of human resources | 24 | |

| Creating new jobs based on technology and current conditions | 22 | |

| Increasing communication and two-way interaction between the tourist and the destination organization | 18 | |

| Virtual organizations are open in all conditions | 23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morabi Jouybari, H.; Ghorbani, A.; Mousazadeh, H.; Golafshan, A.; Akbarzadeh Almani, F.; Dénes, D.L.; Krisztián, R. Smartphones as a Platform for Tourism Management Dynamics during Pandemics: A Case Study of the Shiraz Metropolis, Iran. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054051

Morabi Jouybari H, Ghorbani A, Mousazadeh H, Golafshan A, Akbarzadeh Almani F, Dénes DL, Krisztián R. Smartphones as a Platform for Tourism Management Dynamics during Pandemics: A Case Study of the Shiraz Metropolis, Iran. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054051

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorabi Jouybari, Hadigheh, Amir Ghorbani, Hossein Mousazadeh, Azadeh Golafshan, Farahnaz Akbarzadeh Almani, Dávid Lóránt Dénes, and Ritter Krisztián. 2023. "Smartphones as a Platform for Tourism Management Dynamics during Pandemics: A Case Study of the Shiraz Metropolis, Iran" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054051

APA StyleMorabi Jouybari, H., Ghorbani, A., Mousazadeh, H., Golafshan, A., Akbarzadeh Almani, F., Dénes, D. L., & Krisztián, R. (2023). Smartphones as a Platform for Tourism Management Dynamics during Pandemics: A Case Study of the Shiraz Metropolis, Iran. Sustainability, 15(5), 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054051

.jpg)