Towards Inquiry-Based Learning in Spatial Development and Heritage Conservation: A Workshop at Corviale, Rome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

From Complexity and Uncertainty to Inquiry-Based Learning

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results of the Expanded Workshop

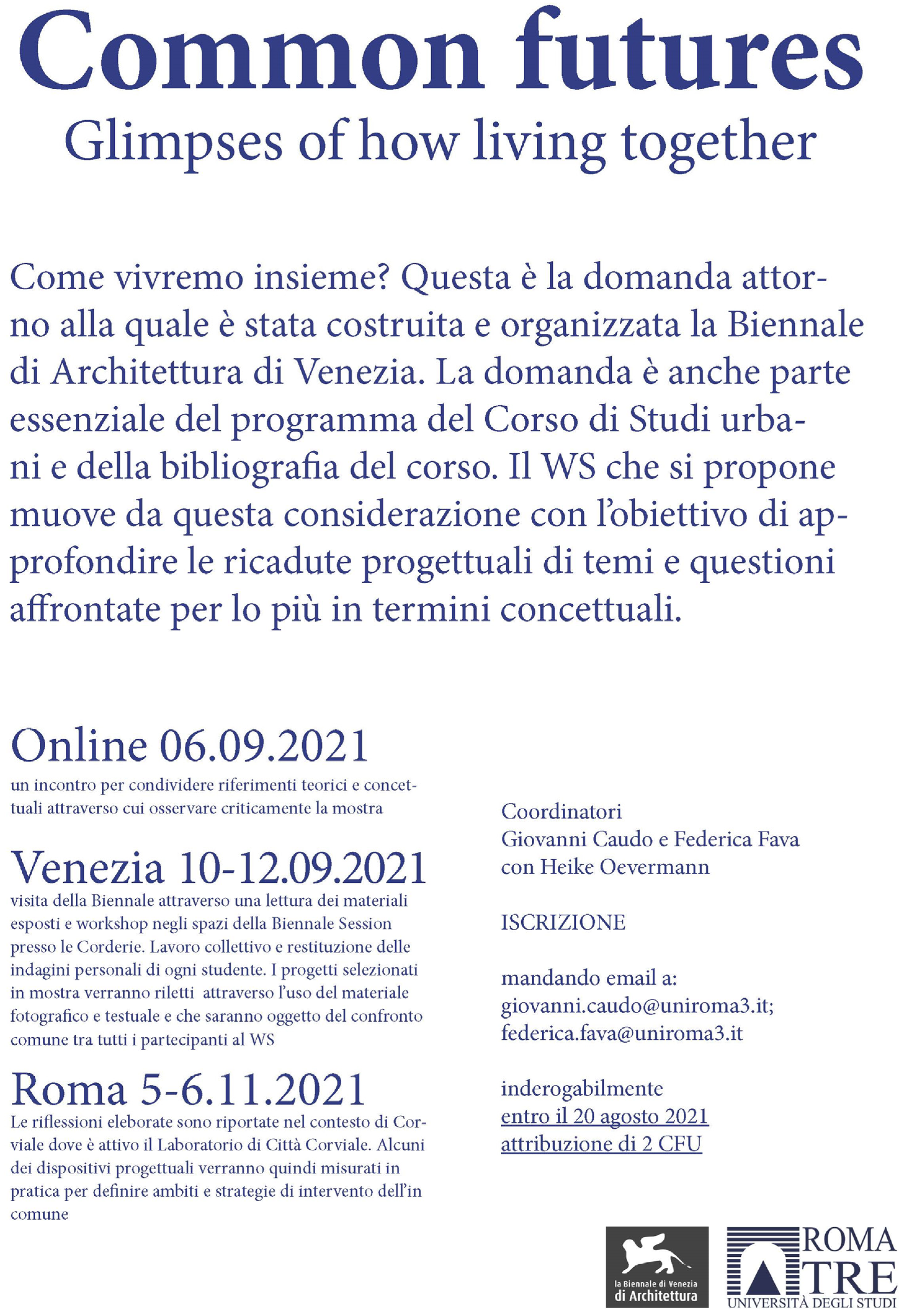

4.1. Pre-Workshop and the Biennale Exploration

4.2. Rome: Exploring Corviale

4.3. Studying at and with Corviale

4.4. Outputs

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morin, E. Les Sept Savoirs Nécessaires à l’éducation Du Futur; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1999; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000117740_fre (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- Ajello, A.R. Method of Knowledge and the Challenges of the Planetary Society: Edgar Morin’s Pedagogical Proposal. World Futures 2005, 61, 511–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, H.; Megarry, W.; Potts, A.; Jyoti, H.; Debra, R.; Yunus, A.; Eduardo, B.; May, C.; Greg, F.; Sarah, F.; et al. Global Research and Action Agenda on Culture, Heritage and Climate Change; ICOMOS & ISCM CHC: Charenton-le-Pont, France; Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/2716/ (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- Jigyasu, R. Heritage and Resilience. Issues and Opportunities for Reducing Disaster Risks. Background Document for a Session on “Heritage and Resilience”, Geneva, Switzerland, 19–23 May 2013; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roders, A.P.; Bandarin, F. (Eds.) Reshaping Urban Conservation: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach in Action; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegmeijer, E.; Veldpaus, L. (Eds.) A Research Agenda for Heritage Planning: Perspectives from Europe; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/gbp/a-research-agenda-for-heritage-planning-9781788974622.html (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Amenta, L.; Russo, M.; van Timmeren, A. (Eds.) Regenerative Territories: Dimensions of Circularity for Healthy Metabolisms; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. The Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Verdini, G. Planetary Urbanisation and the Built Heritage from a Non-Western Perspective: The Question of ‘How’ We Should Protect the Past. Built Herit. 2017, 1, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N. (Ed.) Implosions/Explosions. Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization; JOVIS: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention. 2000. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list?module=treaty-detail&treatynum=176 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Council of Europe. Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. 2005. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Presidency of the Council of the European Union. Urban Agenda for the EU: Pact of Amsterdam; Council of European Union: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grin, J.; Rotmans, J.; Schot, J. Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study Of; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Transitions-to-Sustainable-Development-New-Directions-in-the-Study-of-Long/Grin-Rotmans-Schot/p/book/9780415898041 (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- Lanz, F.; Pendlebury, J. Adaptive reuse: A critical review. J. Archit. 2022, 27, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, S.; Holtorf, C. Uncertain futures. In Heritage Futures: Comparative Approaches to Natural and Cultural Heritage Practices; Harrison, R., DeSilvey, C., Holtorf, C., MacDonald, S., Bartolini, N., Breithoff, E., Fredheim, H., Lyons, A., May, S., Morgan, J., et al., Eds.; UCL Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020; pp. 263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Mieg, H.A. (Ed.) Inquiry-Based Learning—Undergraduate Research: The German Multidisciplinary Experience; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Boelens, L. A Flat Ontology in Spatial Planning: Opening Up a New Landscape or Just a Dead End? DISP—Plan Rev. 2021, 57, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D.C. Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presents: Temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2001, 7, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; DeSilvey, C.; Holtorf, C.; MacDonald, S.; Bartolini, N.; Breithoff, E.; Fredheim, H.; Lyons, A.; May, S.; Morgan, J.; et al. (Eds.) Heritage Futures: Comparative Approaches to Natural and Cultural Heritage Practices; UCL Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. Whose heritage? Un-settling ‘the heritage’, re-imagining the post-nation. In The Politics of Heritage: The Legacies of Race; Littler, J., Naidoo, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 21–31. Available online: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uniroma3-ebooks/detail.action?docID=199418 (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Roders, A.P. The Historic Urban Landscape Approach in Action: Eight Years Later. In Reshaping Urban Conservation: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach in Action; Creativity, Heritage and the City; Roders, A.P., Bandarin, F., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 21–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Knippenberg, K.; Boonstra, B.; Boelens, L. Communities, Heritage and Planning: Towards a Co-Evolutionary Heritage Approach. Plan. Theory Pract. 2022, 23, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSilvey, C.; Harrison, R. Anticipating loss: Rethinking endangerment in heritage futures. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2020, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSilvey, C.; Fredheim, H.; Fluck, H.; Hails, R.; Harrison, R.; Samuel, I.; Blundell, A. When Loss is More: From Managed Decline to Adaptive Release. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2021, 12, 418–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euler-Rolle, B. Management of Change—Systematik der Denkmalwerte. In Die Veränderung von Denkmalen; Wieshaider, W., Ed.; Facultas: Vienna, Austria, 2019; pp. 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Fava, F. Commoning Adaptive Heritage Reuse as a Driver of Social Innovation: Naples and the Scugnizzo Liberato Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Making-Anthropology-Archaeology-Art-and-Architecture/Ingold/p/book/9780415567237 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Tremp, P.; Hildbrand, T. Forschungsorientiertes Studium—Universitäre Lehre. Das “Zürcher Framework” zur Verknüpfung von Lehre und Forschung. In Einführung in die Studiengangentwicklung; Brinker, T., Tremp, P., Eds.; DGWF–Hochschule und Weiterbildung: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Oevermann, H.; Erek, A.; Hein, C.; Horan, C.; Krasznahorkai, K.; Gøtzsche Lange, I.S.; Manahasa, E.; Martin, M.; Menezes, M.; Nikšič, M.; et al. Heritage Requires Citizens’ Knowledge: The COST Place-Making Action and Responsible Research. In The Responsibility of Science; Mieg, H.A., Ed.; Studies in History and Philosophy of Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oevermann, H.; Escherich, M.; Engelmann, I. Untersuchungen zum industriellen Erbe. Community-Orientierung als Weiterentwicklung des Forschenden Lernens’ 2022, 2, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, L. Warum Forschendes Lernen nötig und möglich ist. In Forschendes Lernen im Studium: Aktuelle Konzepte und Erfahrungen; Huber, L., Ed.; UVW: Berlin, Germany, 2009; Volume 10, pp. 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, L. Inquiry-Based Learning in Architecture. In Inquiry-Based Learning—Undergraduate Research: The German Multidisciplinary Experience; Mieg, H.A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S.K.; Reynolds, R.B.; Tavares, N.J.; Notari, M.; Yi Lee Wing, C. 21st Century Skills Development Through Inquiry-Based Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-10-2481-8 (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- World Economic Forum. The Future of Jobs Report 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2020.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Wang, X.; Guo, L. How to Promote University Students to Innovative Use Renewable Energy? An Inquiry-Based Learning Course Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumann, S.; Ohl, U.; Schulz, J. Inquiry-Based Learning on Climate Change in Upper Secondary Education: A Design-Based Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenHeritage website. Available online: https://openheritage.eu/ (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Braschi, S.S. Il Pubblico re-esiste in periferia. L’esperienza del Laboratorio di Città Corviale. In Storie Di Quartieri Pubblici. Progetti e Sperimentazioni per Valorizzare l’abitare; Delera, A., Ginelli, E., Eds.; Mimesis: Sesto San Giovanni, Italy, 2022; pp. 279–285. [Google Scholar]

- Caudo, G.; Regenerate Corviale. Future Housing. Battista, A., Ed.; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/84064 (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Aernouts, N.; Cognetti, F.; Maranghi, E. Introduction: Framing Living Labs in Large-Scale Social Housing Estates in Europe. In Urban Living Lab for Local Regeneration: Beyond Participation in Large-Scale Social Housing Estates; The Urban Book Series; Aernouts, N., Cognetti, F., Maranghi, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudo, G. La città pubblica. Urbanistica 2011, LXIII, 118–121. [Google Scholar]

- Direzione Generale Creatività Contemporanea. Architetture del Secondo 900. Available online: http://www.architetturecontemporanee.beniculturali.it/architetture/index.php (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Bonomo, B. Il “serpentone” conteso. Breve storia politica di un simbolo dell’edilizia popolare romana/The Disputed “Big Snake”. A Brief Political History of a Social Housing Symbol in Rome. iQuaderni di Urbanistica Tre, 2023; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Laura Peretti Architects. Regenerare Corviale. 2015. Available online: https://www.lauraperettiarchitects.com/project/rigenerare-corviale/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Laboratorio Città Corviale Website. Available online: https://laboratoriocorviale.it/chi-siamo/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Cognetti, F.; Castelnuovo, I. Mapping San Siro lab: Experimenting grounded, interactive and mutual learning for inclusive cities. Trans. Assoc. Eur. Sch. Plan. 2019, 3, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camillo, B.; Bianchetti, C. Lifelines: Politics, Ethics, and the Affective Economy of Inhabiting; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caudo, G.; Fava, F.; Oevermann, H. Towards Inquiry-Based Learning in Spatial Development and Heritage Conservation: A Workshop at Corviale, Rome. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4391. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054391

Caudo G, Fava F, Oevermann H. Towards Inquiry-Based Learning in Spatial Development and Heritage Conservation: A Workshop at Corviale, Rome. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4391. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054391

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaudo, Giovanni, Federica Fava, and Heike Oevermann. 2023. "Towards Inquiry-Based Learning in Spatial Development and Heritage Conservation: A Workshop at Corviale, Rome" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4391. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054391

APA StyleCaudo, G., Fava, F., & Oevermann, H. (2023). Towards Inquiry-Based Learning in Spatial Development and Heritage Conservation: A Workshop at Corviale, Rome. Sustainability, 15(5), 4391. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054391