1. Introduction

With the full penetration of 4G networks and the arrival of 5G technology, the e-commerce model has diversified, and live-streaming (LS) e-commerce has gradually entered the public view. Along with the rise of head streamers, the LS e-commerce industry has seen a spurt in development. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, LS e-commerce perfectly suited the needs of the people who were under closed management for entertainment and shopping and helped sell unsalable products in the epidemic area, playing a major role in rural revitalization, economic recovery and employment [

1]. Influencer Marketing Hub released data showing an upward trend in the growth of the global live e-commerce industry from March 2020 to July 2021, with a 76% increase in live purchases and a tenfold higher conversion rate through live streaming compared to other forms of e-commerce. According to the Coresight Research, the U.S. live-streaming market is forecast to reach USD 11 billion in 2022 and around USD 25 billion by 2023. By comparison, the firm predicts China’s live shopping industry to reach USD 300 billion in 2022. Meanwhile, about 26 percent of people currently prioritize live retail, which will double in the next 12 to 18 months, according to a Gartner Research survey. This shows that with the accelerated formation of online consumption habits among users during the epidemic, watching live streams and shopping in them has become one of the mainstream habits of Internet users. However, with the increase in the number of LS practitioners, China’s LS e-commerce industry is becoming increasingly saturated, and the overall growth rate has begun to slow down and gradually entered the era of fighting for user stock; whether users spend in LS for a long time has become the key to the survival of LS e-commerce platforms. Therefore, the study of users’ consumption behavior in LS e-commerce has strong practical significance.

For the study of consumer purchasing behavior, scholars have mostly used perceived value to explain it. Cao et al. [

2] found that perceived value positively and significantly affects customer engagement behavior through empirical analysis. Yan et al. [

3] proposed that there is a mediating effect of perceived value between live characteristics and purchase behavior. Based on previous research by scholars, the influence of perceived value on users in the e-commerce environment has been verified, but most of them are direct measures of the influence of perceived value on purchase behavior, lacking in-depth research on the path of influence. In the case of LS e-commerce, the e-commerce streamer is a salesperson and an opinion leader and is the link between the product and the consumer, while the brand, reputation and quality of the product are also the focus of consumers’ consideration, and the final purchase behavior of the consumer is largely based on trust in the product and trust in the streamer’s recommendation. However, in existing studies, consumer trust in LS e-commerce is often treated as a whole and not in detail. This suggests that future research in LS e-commerce should focus on exploring what value consumers can perceive when shopping live and how consumers’ perceived value leads to trust and ultimately continued consumption in LS e-commerce.

The objective of this study is to analyze the factors influencing consumers’ Continuous Purchase Intention in LS e-commerce, based on the stimulus–organism–response (SOR) framework, and to explore the mechanisms of perceived LS e-commerce from three dimensions: utilitarian value, hedonic value and social value. We use a questionnaire to collect data and use structural equation modeling (SEM) to analyze and validate the theoretical framework and hypotheses, in order to provide reference for the marketing activities of consumers and related companies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: First, we review the literature related to this study. Second, we propose hypotheses and theoretical models based on existing studies. Third, the questionnaire item design, sampling and questionnaire collection for this study are presented. Fourth, the research model and hypotheses are tested empirically, and the results of the study are presented. Fifth, a discussion and conclusion based on the research results are presented. Finally, the theoretical and managerial implications of this study are summarized.

2. Literature Review

2.1. SOR Theory

The stimulus–organism–response (SOR) model originated in environmental psychology and was originally proposed by environmental psychologists Mehrabian and Russell to explain and predict the effects of different environmental stimuli on human cognition, emotions and behaviors [

4]. The SOR model of Mehrabian et al. is a modified and optimized version of the S-R model proposed by Woodworth, with the addition of the “O” variable, which begins to focus on the inner consciousness of organisms such as humans. S (stimulus) refers to the external factors that can influence an individual, and the model assumes that different external stimuli have different effects on a person’s internal state and thus determine the person’s decision-making behavior. The SOR model, in which stimulus and response are linked by a set of intrinsic variables, has been widely applied to the systematic analysis of human behavioral intentions by focusing on intrinsic emotional and cognitive factors.

Donovan and Rossiter first applied the SOR model in a retail environment to study the influence of the retail store environment on customer buying behavior [

5]. Zhou applied the SOR model to explore how platform characteristics, knowledge characteristics and contributor characteristics in the knowledge payment market act as stimuli to influence consumers’ perceived value and thus their willingness to purchase [

6]. With the prevalence of online shopping and e-commerce, the SOR model was applied to the Internet environment to investigate the influence of environmental factors on consumers’ willingness to use the Internet and purchase online in an online environment.

2.2. Continuous Purchase Intention

Continuity of purchase intention is to some extent closely related to consumer loyalty and is an important psychological indicator for predicting actual repurchase behavior. Jones and Sasser [

7] were the first to suggest that after purchasing a good or receiving a service, consumers will generate a subjective perceived value based on their last shopping or service experience. They believed that after purchasing a good or receiving a service, consumers will develop a subjective perceived value based on their last experience, and they will form the intention to purchase again. At present, the academic community is mostly focused on consumer psychology, such as perceived value, consumer trust and perceived risk. Chai et al. [

8] found that consumer perceptions such as perceived usefulness, perceived value and reliability can significantly influence consumers’ intention to continue buying. Zhao et al. [

9] found that consumers’ intention to continue buying is influenced by consumers’ habits, which are due to the role of consumers’ trust building. Wang and Lu [

10] found that satisfaction, trust and product perceived complexity are the most important factors influencing determinants of continued purchase intention. Based on S-O-R theory, Huang et al. [

11] showed that both perceived trust and perceived entertainment significantly influenced consumers’ intention to continue purchasing.

2.3. Perceived Value

“Shopping value” is an overall assessment of the subjective and objective factors that make up a complete shopping experience [

12]. It is widely used by scholars in explaining and predicting consumer preferences and buying behavior. Sheth et al. [

13] expanded the field of perceived value on this basis to include functional, social, emotional, conditional and cognitive value dimensions. Previous research related to perceived value has focused on utilitarian and hedonic value; Chiu [

14] et al. used online shops as a study to verify that utilitarian and hedonic values positively influenced repeat purchase intentions; Lin and Lu [

15] used utilitarian value and hedonic value as mediating variables and social influence as stimulus variables to predict consumer acceptance of mobile social networks. However, in the context of social commerce, people are not only interested in the satisfaction of utilitarian and hedonic values, such as convenience and enjoyment, but also start to pursue social values, such as interaction with others and self-fulfillment [

16,

17]. Therefore, this paper classifies perceived value into utilitarian, hedonic and social values and investigates their influence on consumers’ continued purchase intention in LS e-commerce.

2.4. Consumer Trust

In the field of marketing, trust research has always been a topic that scholars cannot ignore, and with the development of the Internet, the diversity that traditional commerce presents in the process of transforming into e-commerce has made trust a growing concern for scholars. For the definition of trust in e-commerce platform transactions, Mcknight et al. [

18] suggested that trust means that one party believes that the other party has one or more characteristics that are beneficial to them. In contrast, Li [

19] argued that trust is a rational choice to reduce transaction costs and is a product of modernization. Following the theoretical foundations of the previous authors, the academic community has also classified the types of trust in e-commerce platforms. Komiak and Benbasat [

20] proposed a new trust model that distinguished between cognitive and affective trust, through which consumer trust in offline/online commerce is defined as trust in multiple entities: e.g., companies, agents (sellers, salespeople, websites, SNS administrators), products and markets/channels (individuals, Internet). As the object of this paper is LS e-commerce, compared to traditional e-commerce, consumers do not need to contact or understand entities such as companies, administrators and channel vendors; they only need to face the streamer and the product in the live room. Based on this, this paper divides trust in LS e-commerce into trust in streamer and trust in product. “Trust in streamer” is measured based on three aspects (i.e., trustworthiness of the streamer, quality service and streamer recommendation) [

21]. “Trust in product” refers to the product meeting expectations, the appearance and functionality of the product being consistent with the publicity and the after-sales service of the product being perfect [

22].

3. Research Hypotheses

3.1. Perceived Value

3.1.1. Utilitarian Value

In the specific context of online shopping, utilitarian value refers to the degree to which the features, price and quality offered by a product or service are consistent with the consumer’s expected utility, and consumers experience the utilitarian value of products and services when their expected requirements are fully satisfied [

23]. When shopping online, especially when dealing with smaller independent sellers, consumers are often more concerned with the legitimacy of the supplier and the authenticity of the product [

24]. At the same time, in traditional e-commerce, consumers cannot touch and test products in person before purchasing and can only learn from product specifications, pictures and other people’s reviews, all of which can increase the perceived risk of shopping online. Consumers who buy clothes online often find that the clothes they receive do not match their expectations and do not look good on them. In the context of LS e-commerce, streamers try on clothes either in person or by hiring models to present a full range of product information to consumers in an unedited manner, giving them systematic information about the product and increasing their trust [

25,

26].

Based on common shopping psychology, the quality and price of a product are often the first consideration for consumers and an important source of perceived utilitarian value. Consumers always want to buy good quality goods at a lower price, and in live events, streamers offer discount coupons and special offers. Sometimes, consumers complain that prices are too high and can negotiate lower prices with the streamer in real time. Studies show that low prices increase perceived risk [

27]. While consumers are more willing to try products at low prices, when prices are too low, they can instead increase the perceived risk to consumers [

28]. In addition, consumers tend to shop around and form an expected price in their mind by comparing offers from various channels. When the price from alternative channels is lower than this expected price, it can reduce consumers’ perceived profit loss and enhance the attractiveness of the product to consumers [

29]. When the price of the alternative channel is lower than the expected price, it reduces the perceived loss and increases the appeal of the product to the consumer.

From the study of consumer trust above, in the context of LS e-commerce, this could mean that consumers believe that the information they receive is authentic and that they can purchase a more suitable and affordable product. Through LS, the utilitarian value in terms of authenticity and price can be increased, and consumers’ uncertainty about the streamer and the product should be alleviated and their interest needs met. In other words, consumers may have more trust in the streamer and the product and increase their willingness to buy. Therefore, the following hypothesis is made in this paper.

Hypothesis 1a (H1a). The utilitarian value of LS e-commerce positively influences consumers’ trust in streamers.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b). The utilitarian value of LS e-commerce positively influences consumers’ trust in products.

3.1.2. Hedonic Value

Enjoyment value refers to the degree of fun, pleasure and enjoyment that consumers experience while watching a live stream. Webcasts are highly entertaining, and consumers can easily achieve a psychological state of excitement and pleasure when shopping [

30]. Lv found through empirical research that entertainment in live streaming gives viewers a sense of immersion and thus motivates consumers to continue watching [

31].

Studies have shown that text-based chat rooms on LS platforms enhance social bonds, and these social bonds improve consumers’ positive emotions such as satisfaction and attachment, resulting in emotional commitment [

32]. At the same time, sending pop-ups as a format gives users a strong sense of engagement and makes them feel happy [

33]. The gift and dress-up special effects features offered by the various LS platforms also create a fun and exciting experience for consumers [

34].

In interpersonal interactions, trust is very often a subjective assessment based on emotions. In this study, it is formed through an emotional bond between the consumer and the streamer. Shopping value is related to the customer’s feelings and emotions, such as pleasure (hedonic) or a way to satisfy their needs (utilitarian) [

35]. In the process of watching an LS, consumers gain hedonic value from the interactions and activities, enhancing the shopping experience and the psychological intimacy between the consumer and the streamer, bringing the consumer and the streamer closer together and prompting greater confidence in the streamer’s ability, charm and character in providing the service and generating trust [

36]. At the same time, the streamer presents the product in a novel way, which may also enhance the consumer’s emotions and feelings, thus increasing trust in the product and leading to purchase behavior. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 2a (H2a). The hedonic value of LS e-commerce positively influences consumer trust in streamers.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b). The hedonic value of LS e-commerce positively influences consumers’ trust in products.

3.1.3. Social Value

Social value has often been overlooked in previous scholarly delineations of the dimensions of perceived value. Sweeney and Soutar [

37] argue that consumers do not only evaluate products and services through utilitarian and hedonic values, but social values are also involved. In the context of the increasing socialization of e-commerce, sometimes customers use products in order to gain the approval of social groups, either to conform to their social norms or to present their intrinsic image [

29]. By evaluating recent articles on social influence in online retailing, Kalia et al. point out that social influence has the power to influence people’s intentions and decisions [

38]; for example, blogger recommendations on social media directly influence customers’ buying and recommending behaviors [

39] and form trust in products and brands [

40].

Social identity refers to an individual’s recognition that he or she belongs to a particular social group and the emotional and value significance that comes with membership of that group. Consumers tend to shop in places where they can meet people of their own kind; they feel a greater sense of belonging and identity. LS provides audience feedback through real-time pop-ups that can help shoppers infer the characteristics of other users, the popularity of a product and whether it will be accepted by their social networks [

34]. In addition, consumers can assess whether the professionalism, appearance and charisma of the streamer matches their preferences while watching the live stream and thus determine whether they can trust the products recommended by the streamer.

The cognitive basis of identity formation in the process of self-categorization further increases the emotional motivation that individuals invest in relationships [

41]. An empirical study has verified that increased consumer identification enhances customer loyalty to a company [

42]. Based on this, we predict that the social identity gained by viewers through LS can perceive social value and increase trust in the streamer. If the product purchased during the live broadcast improves one’s image and can become a symbol of the consumer’s identity and status, making one more confident, the consumer should also have more trust in the product and through trust, the willingness to purchase. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed in this paper.

Hypothesis 3a (H3a). The social value of LS e-commerce positively influences consumers’ trust in streamers.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b). The social value of LS e-commerce positively influences consumers’ trust in products.

3.2. Consumer Trust

Based on previous research on consumer trust in traditional e-commerce, combined with the context of LS e-commerce, this paper divides consumer trust into trust in the streamer and trust in the product. In social psychology, trust can be considered as a positive attitude. Coherence theory, a classic theory for studying the relationship between consumers’ attitudes towards information sources and information objects, is widely used in the field of studying consumer psychology. The theory states that people have the same or different attitudes towards various people and things around them due to different evaluations and that these attitudes can be independent of each other. However, when one of the cognitive objects (the information source) sends a message related to the other (the information object), the attitudes between the two are related. If individuals have the same attitudes towards the two, consistency is created, while if they are different, a range of negative emotions such as tension and anxiety are caused, thus creating a drive to adjust the original attitudes towards the cognitive object in order to produce consistent cognitions and attitudes. In this process, individuals selectively support or avoid certain information in order to reduce cognitive dissonance [

43]. Wang believes that in LS e-commerce, consumers obtain the most information through the streamer, and their evaluation of the product receives their level of trust in the information source [

44]. As the relationship between these two types of trust remains untested, we hypothesize that in LS e-commerce, the streamer’s evaluation of the product as an information source will influence consumers’ attitudes towards the product and that if consumers trust the streamer enough, they will be more likely to approve of the product they recommend. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed in this paper.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Consumer trust in a streamer positively influences consumer trust in a product.

Trust is the cornerstone of business transactions, and consumers make purchase decisions based in large part on their trust in the merchant and its products. Trust can influence users’ judgment and behavior in online environments [

45]. However, because of the uncertainty and information asymmetry associated with online shopping, online trust relationships are difficult to maintain. In the process of LS promotional products, the consumer and the product are separated, and the user is unable to personally feel and identify whether the item meets their expectations, so trust in the streamer becomes the key to making a purchase decision [

19]. The positive impact of trust on consumers’ purchase intentions has been verified through previous studies. Liu et al. [

46] found that trust in weblebrities in LS can significantly and positively influence fans’ purchase decisions. Tsai and Hung [

47] pointed out that consumers with high emotional trust are more willing to stick to online platforms that they feel satisfied with, thus positively influencing continued purchase intentions.

Although online consumption models vary in terms of platforms, methods and target users, they are still essentially consumption in exchange for products or services, and Jarvenpaa [

48] identifies trust as a key factor in stimulating consumer purchase and repurchase behavior. In the online shopping process, when consumers perceive that online merchants can provide high quality products and services and focus on the realization of consumer rights, consumers will subjectively eliminate the influence of uncertainties in the shopping environment. Zhou and Fan [

22] pointed out that consumers’ trust in products stems from their technical trust in the quality of the product and their institutional trust in the after-sales guarantee. Based on the traditional shopping concept of “you get what you pay for”, consumers are concerned about the quality of products that are too low priced, and perfect after-sales service can alleviate consumers’ uncertainty about products and reduce their perceived risk. In addition, when agricultural products are broadcast live, streamers often bring the products live on farms, showing the production traceability of agricultural products in real time, which to a certain extent also reduces consumers’ concerns and uncertainties and reduces the perceived risk. It has been shown that a reduction in perceived risk can significantly increase consumer trust. Macdonald et al. [

49] also found that consumers’ trust in a product has a positive impact on continuous purchase intentions.

Based on the above analysis, we believe that trust in streamers and products can positively influence consumers’ purchase intentions. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed in this paper.

Hypothesis 5a (H5a). Trust in streamers positively influences consumer’ continuous purchase intentions.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b). Trust in products positively influences consumer’ continuous purchase intentions.

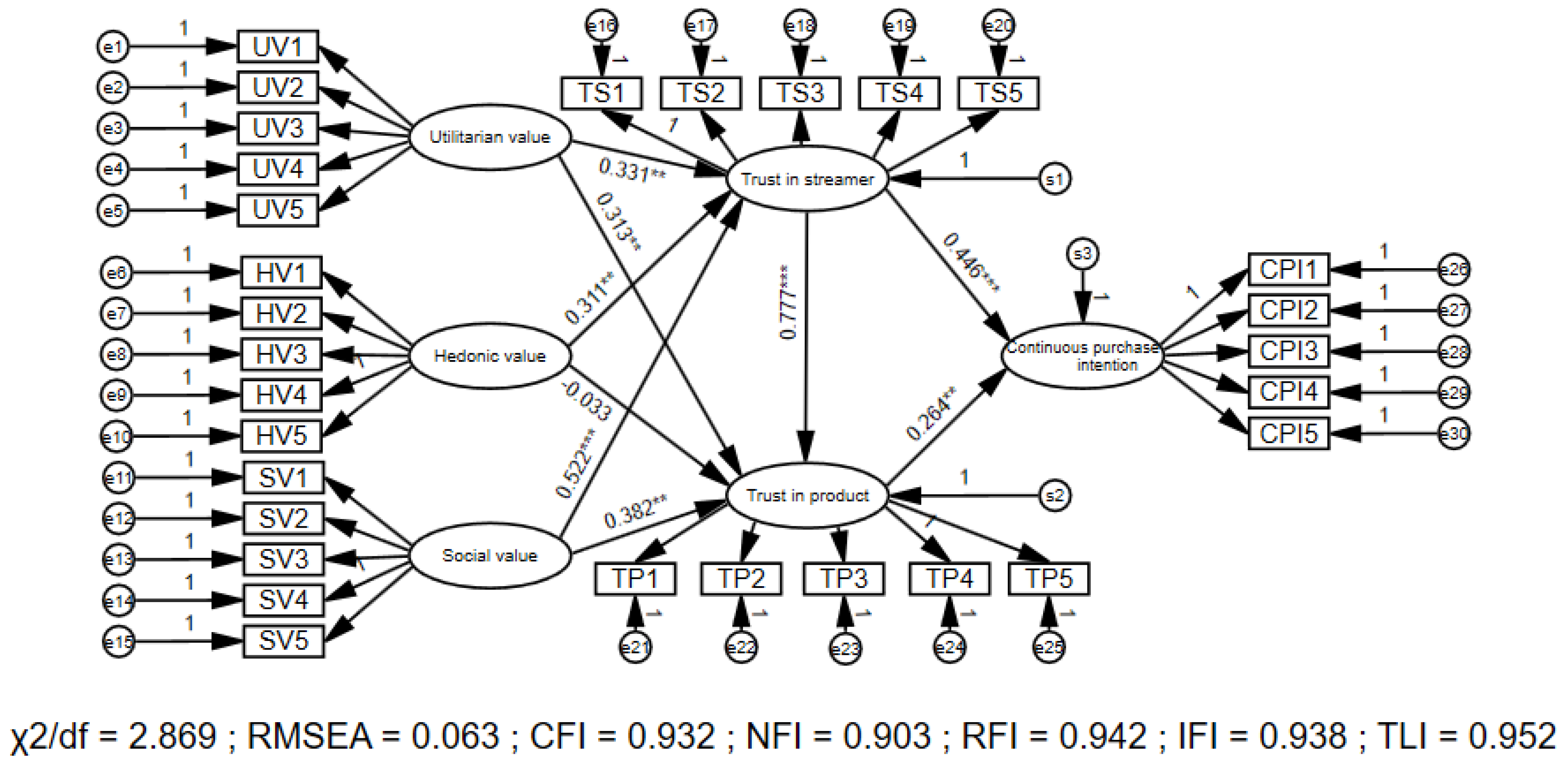

Based on the theoretical foundation and research hypotheses above, the following theoretical model is proposed, as shown in

Figure 1. Among them, utilitarian value, hedonic value and social value as the perceived value in live e-commerce belong to the external stimulus that inspires consumers to generate purchase intention (S); trust in the streamer and trust in the product in LS as mediating variables, reflecting the psychological changes of consumers, constitute the mediating transmission mechanism to the perceived value (O); and finally the response that inspires consumers to generate continuous purchase intention (R). This theoretical model takes consumers’ trust as a mediating variable and investigates the transmission mechanism of perceived value on consumers’ willingness to sustain purchase in live e-commerce from the perspective of consumers’ psychological changes, and the model will be verified by means of the experiments in the following sections.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Questionnaire and Measurements

This study involves six variables to be measured: utilitarian value, hedonic value, social value, trust in streamer, trust in product and consumer’ continuous purchase intentions. To ensure the validity of the scale, all the question items were designed by drawing on previous studies and making modest modifications according to the research context of this paper. The specific design of the scale questions is shown in

Table A1; for the utilitarian value dimension, we refer to the design of Sweeney and Soutar [

37], Chiu et al. [

14] and Wongkitrunrueng [

34] and focus on the authenticity of live streaming and the degree of discount; for the hedonic value dimension, we refer to the design of Sweeney and Soutar [

37] and focus on the entertainment of live streaming; for the measurement of social value dimension, we refer to Sweeney and Soutar [

37] and Wongkitrunrueng [

34], focusing on the examination of social identity and self-consistency and the measurement of trust in streamer dimension and trust in product dimension adapted from Gefen and Straub [

50] and Wongkitrunrueng [

34]. Finally, the measure of consumers’ continuous purchase intention was adapted from Dodds et al. [

51] and Dubinsky et al. [

52].

This study collected data using a questionnaire survey method. Due to the pandemic, we distributed the questionnaire through the “Questionnaire Star” platform. The questionnaire consists of two parts. The first part is a survey of the basic characteristics of the respondents, which is used to understand the behavioral characteristics of users who participate in live-streaming shopping, including gender, age, occupation, education level and the types of streamers they mainly watch. Considering that live-streaming e-commerce is a relatively new marketing model, we set a question to exclude respondents who have never had contact with live-streaming e-commerce. The second part is a specific scale that measures the role of trust in the mechanism of consumers’ continuous purchasing intention in live-streaming e-commerce, consisting of 30 measurement items. The scale uses a Likert five-point scale, with integer values from 1 to 5 representing “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. Participants were asked to recall their most memorable streamer and to evaluate their experience based on their real-life experiences while watching the streamer’s live-stream sales. We adjusted some statements based on pre-surveys and formed the final questionnaire.

After the survey, a total of 328 questionnaires were collected. After eliminating questionnaires that had never been in contact with live-streaming e-commerce, were logically inconsistent, had excessively long or short answer times, were repeated or had completely identical answer options, 213 valid questionnaires were collected, with a valid response rate of 64.94%.

4.2. Sample

The questionnaire was analyzed, and the sample characteristics statistics were obtained as shown in

Table 1. In terms of gender, 166 women (77.9%) made up the majority compared to 47 men (22.1%). We speculate that the possible reasons for this were (1) women are more keen on online shopping and therefore care more about this topic and therefore fill it out more; (2) social software pushes relevant information to people who are already interested in such topics, causing a greater imbalance in the gender ratio. Since the questions and hypotheses in this study do not involve gender, we conducted a hypothesis test on the male and female questionnaires separately and found that the results obtained were not significantly different, so we put the male and female questionnaires together for analysis; in terms of age and education, this questionnaire was mainly issued to the university student group, so 18–25 years old accounted for the vast majority (90.1%), and those with education above bachelor’s degree were also as high as 94.4%. As this research was used for academic research, university students have a stronger acceptance and spending power for LS, and the credibility of the completed questionnaire is higher. Monthly income of less than CNY 3000 accounted for (84.5%). According to «The 50th China Internet Network Development Statistics Report» released by CNNIC, the group of Internet users between 20 and 50 years old accounted for 74.2%, while the age of Internet users watching live broadcasts was even lower, and those who were willing to participate in online questionnaires might also be mainly young people, so their income was relatively low. In addition, most of the subjects (72.3%) mainly watched the live broadcasts of Internet celebrities, indicating that Internet celebrity live broadcasts are favored by young people and attract more traffic.

4.3. Reliability and Validity Analysis

The limitations of the questionnaire may lead to the existence of common method bias (CMB). Therefore, a CMB test was conducted to ensure that participants were eligible to complete the questionnaire. In this paper, we used Harman’s single-factor test and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) together, and we included six variables in the EFA model. The results of the EFA showed that the eigenvalues of all six factors were greater than 1.0, and the percentage of variance explained by the first common factor was 36.185%, which was less than 40%, so it can be concluded that there was no serious CMB in this study [

53].

Reliability refers to the reliability of the scale, mainly for the purpose of measuring the internal consistency of the questionnaire, and high consistency indicates high reliability of the measurement scale. The index of reliability test is Cronbach’s α value; the higher Cronbach’s α indicates the better scale design, higher reliability when it is greater than 0.8, and Cronbach’s α coefficient needs to consider redesigning the scale if it is below 0.6. In this paper, the data were tested for reliability by SPSS26.0, as shown in

Table 2, the Cronbach’s α values of all variables in all scales were greater than 0.7, the reliability reached a good level, and the reliability of latent variables within the questionnaire was good, which indicated that the scales in the questionnaire were more reliable.

The validity test can accurately measure the degree of response of the test results to what is measured, so this study used factor analysis to examine the validity of the variable question items in terms of content validity and structural validity. In terms of content validity, the scales of this study are all modified and proposed based on the reference to the research scales of domestic and foreign scholars’ literature, combined with the live e-commerce context of this study, and also refer to the participation behaviors and motivations mentioned by the in-depth users of live e-commerce in the in-depth interviews, constantly modify the content and structure of the scales and measurement questions and pass the reliability test of the pre-research; therefore, the scales of this study have better content validity.

In terms of structural validity, two data indicators, convergent validity and discriminant validity, were used in this study for testing [

54]. The average variance extraction (AVE) and the combined reliability CR were used as the measures of convergent validity, and the results are shown in

Table 2. The analysis was conducted for a total of 6 factors and 30 analysis items. From the data results, the AVE values of the six factors are greater than 0.5, and the CR values are higher than 0.7, indicating that the data of this analysis have good convergent (convergent) validity. By analyzing the discriminant validity, the test results are shown in

Table 3. The square root value of AVE corresponding to each factor is greater than the correlation coefficient between factors, indicating that the research data have good discriminant validity.

4.4. Structural Equation Model Analysis

4.4.1. Direct Effects

In this study, AMOS26.0 was used to analyze the structural equation model (SEM) of sample data and explore the relationship between research variables. The model fitting index is used to judge the validity, and the model fitting index obtained by AMOS26.0 analysis is suitable for each index. The results are as follows: ꭓ

2/df = 2.869; RMSEA = 0.063; CFI = 0.932; NFI = 0.903; RFI = 0.942; IFI = 0.938; TLI = 0.952. So, the model fitting validity is good. The path coefficient of the model and its significance level and fitting path test are shown in

Table 4. The results show that utilitarian value positively affects trust in streamers (

) and positively affects trust in products (

), with H1a and H1b being supported. Hedonic value positively affects trust in streamer (

); the correlation coefficient with trust in the product is not significant (

). H2a is supported, but H2b is not supported by the results. Social value positively influences trust in streamer (

) and positively influences trust in the product (

). H3a and H3b are supported. Moreover, all three perceived values are more correlated with trust in streamer than with trust in product.

Trust in the streamer positively influences trust in the product (

); H4 is verified. Trust in streamer positively influences consumers’ continuous purchase intentions (

); H5a is verified. Trust in the product positively influences consumer’s continuous purchase intention (

); H5b is verified. The results of the structural equation model are shown as

Figure 2.

4.4.2. Mediating Effects

To explore the effect of mediation between the two perceived trusts in the model, this paper used the Process plugin compiled by Hayes to conduct a mediation effect test on SPSS 26.0. A bootstrap procedure with 5000 samples was used to construct and test the confidence interval for the mediation effect. The confidence interval was set to 95%, and Model4 (simple mediation model) in the plugin was used to test the mediation effect of trust in streamer and trust in product between perceived value and purchase intention. The results obtained are shown in

Table 5. The mediating effect of utilitarian value through trust in streamer on continuous purchase intention was 0.200 (Boot CI = [0.069,0.361]); the mediating effect of trust in product on continuous purchase intention was 0.129 (Boot CI = [0.020,0.289]). The mediated effect value of hedonic value influencing continuous purchase intention through trust in streamer was 0.119 (Boot CI = [0.023,0.219]). The mediating effect of social value through trust in streamer was 0.189 (Boot CI = [0.062,0.306]); the mediating effect of social value through trust in product was 0.131 (Boot CI = [0.027,0.255]). None of the confidence intervals contained 0. Since the three perceived value and continuous purchase intention main effect relationships existed, the two consumer trusts partially mediated the relationship between perceived value and continuous purchase intention. Moreover, trust in streamer has a higher mediating effect value than trust in product for all three perceived values affecting continuous purchase intention.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Based on SOR theory, this paper constructs a model of consumer’s continuous purchase intention in LS e-commerce with two types of consumer perceived trust as mediating variables, measures the mediating effect of two types of consumer trust (trust in the product and trust in the streamer) by means of a questionnaire and draws the following conclusions from the study.

First, the study found that consumers’ perceived utilitarian, hedonic and social values have a significant and positive impact on their trust in streamers. Specifically, the utilitarian value refers to the streamers’ ability to meet the consumers’ needs for great deals and authentic shopping by providing low-price promotions and real-time display of products during the live broadcast. The hedonic value refers to the entertainment activities, such as lottery and PK, which are commonly used by streamers to enhance the pleasure of the shopping experience and strengthen consumers’ trust in them [

55]. The social value, on the other hand, has a greater impact on trust in streamers than utilitarian and hedonic value. This is because social value represents the future benefits of perceived similarity between consumers and streamers. Streamers can enhance trust by creating a sense of belonging and identity for consumers in the LS e-commerce platform. By utilizing their unique personal charisma and excellent marketing ability, streamers can bring consumers closer to each other and ultimately improve their trust in the platform.

Second, consumers’ perceived utilitarian and social values significantly and positively influence trust in the product. The utilitarian value of products is obtained through good value and after-sale guarantee, which can reduce the uncertainty of product purchase and increase consumers’ trust in the product. Furthermore, consumers’ perceived social value is positively related to their trust in products, as the consistency between the product’s brand image and consumers’ self-concept image enhances consumers’ favorable perception of the product and their level of trust, which is consistent with previous studies such as Sarah et al. [

56]. In contrast, the hedonic value has no direct influence on product trust, as the entertainment activities in LS e-commerce are mainly planned by the streamer; thus, the emotional trust generated from hedonic value perceived by consumers when watching the live stream is often directed towards the streamer rather than the product itself. Therefore, we conclude that perceived utilitarian, social and hedonic values have different impacts on trust in LS e-commerce. Utilitarian and social values are important predictors of trust in products, whereas social value has a greater impact on trust in streamers. Hedonic value is more likely to generate emotional trust in streamers rather than in products.

Third, trust in the streamer significantly and positively influences trust in the product. Based on Osgood and Tennenboum’s consistency theory, people have a drive to motivate themselves to develop consistent perceptions and behaviors towards the object. When the streamer they trust reviews and markets the product, out of trust in the streamer, consumers will also trust the product in order to avoid any dissonance in their perceptions. This could also explain the presence of a large number of celebrity endorsers in modern advertising and the LS of celebrity weblebrities to lead the product.

Fourth, trust in the streamer and trust in the product mediate between perceived value and a consumer’s continuous purchase intentions. LS e-commerce combines LS with e-commerce, satisfying consumers’ utilitarian needs by virtue of its price advantage over other shopping channels; it promotes emotional exchanges between streamers and consumers through various entertainment activities and positive interactions, increasing consumers’ hedonic value. In addition, the social identity of the on-air community and the brand image of the product will increase the perceived social value. The increase in perceived value reduces uncertainty and perceived risk in online shopping, making it easier to build trusting relationships, and building trust can enhance consumer loyalty. When consumers watch a live stream, they evaluate the streamer’s mannerisms, product presentation and product experience. If consumers feel trust in the streamer and have a good buying experience, they will increase their trust and loyalty to the streamer and the product, thus increasing their willingness to continue buying.

Fifth, the trust of the streamer dominates the trust of consumers in LS e-commerce. The results of this study also confirm the important role of trust in streamers in LS e-commerce. LS e-commerce is similar to traditional e-commerce in terms of products, but the biggest difference is that it uses the live broadcast format to act as a link between consumers and companies. The streamer is the key opinion leader and salesperson who controls the entire live broadcast and influences the consumer’s purchasing decisions. Therefore, trust in the streamer has a greater impact on continuous purchase intention than trust in the product.

6. Research Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

With the development of LS e-commerce, the research on consumer purchase intention in LS e-commerce has gradually become an emerging hot issue. In the context of LS e-commerce, this study analyzes the influencing factors of consumers’ continuous purchase intention. Specifically, this study has the following three contributions.

Firstly, this study verifies the mediating role of consumer trust between perceived value and continuous purchase intention. The intermediary role of streamers and products in LS e-commerce can significantly enhance consumers’ continuous purchase intention because both can achieve the transmission of the three values well, and as shown in

Table 5, the intermediary effect of anchors is more obvious. This point can remind merchants to focus on the cultivation of streamers.

Secondly, in recent years, some scholars have distinguished trust in the product from trust in the streamer [

57,

58]. Wongkitrngrueng conducted a study based on this trust division and found that trust in the product can positively and significantly affect trust in the seller. However, given that the scale of LS e-commerce development abroad is too small compared to China, the focus is on small individual sellers, which has considerable limitations. The framework of this study extends previous research on online trust by separating trust in the streamer from trust in the product and finds multiple ways in which both trusts influence consumers’ continuous purchase intentions—trust in the streamer/product to purchase intentions or trust in the streamer to trust in the product and then purchase intentions, which may differ from the above studies. In addition, the antecedents of the two types of trust are different, with utilitarian/hedonic/social values being associated with trust in the streamer while utilitarian/social values are associated with trust in the product.

Thirdly, this paper quotes the consistency theory of Osgood and Tannenbaum [

43] to explain the relationship between the two types of trust, broadening the research perspective of consumer trust. The consistency theory is often used in consumer behavior to explain the presence of a large number of celebrity endorsers in modern advertising, while rarely mentioned in the field of LS e-commerce.

6.2. Managerial Implications

The relevant findings of this paper provide the following insights for companies conducting LS e-commerce marketing campaigns.

First, focus on the actual needs of consumers. The utilitarian value of consumers in LS e-commerce is mainly concerned with price and authenticity. Price advantage is still the key to winning, and users will always favor products with high cost performance. Practice has proven that a large part of the reason why consumers choose live shopping is its better prices than other channels. To achieve the same quality and low price, it is necessary to further optimize the logistics management and reduce the logistics cost of the enterprise through the screening, coordination and integration of the offline supply chain. The centralized sale of goods during LS also reduces labor and inventory costs, allowing for appropriate concessions to be made to consumers, so that they can feel the tangible benefits of high-quality, low-priced products. In addition, the streamer should fully restore the real shopping scene during the process of selling goods, highlighting the process of displaying, trying and processing the products, creating a visual shopping experience for consumers and enhancing their perceived trust in the products [

59].

Second, design entertainment activities. Compared to the traditional online shopping method of browsing static images and text, watching live broadcasts obviously takes more time, and many viewers do not initially intend to shop and watch live broadcasts largely to relieve stress and pass the time. Through the analysis, consumers’ perceived hedonic value can significantly increase their trust in the streamer and thus their willingness to continue purchasing. Therefore, the streamer needs to set up some entertaining activities to relieve the viewers’ boredom and arouse the participation of these potential users. By creating a happy viewing experience, it can inspire the consumers’ emotional trust in the streamer and thus generate continuous purchase intention.

Third, strengthen the skills training and brand building of streamers. Streamers should gradually establish their own LS style in the process, attracting loyal viewers with their personal charm and forming private domain traffic. They should conform to their own brand image when choosing goods to bring to market and accurately grasp the needs of their target customers. Studies have shown that consumers prefer to be supported by information from opinion leaders during LS [

60], so it is important that streamers have comprehensive information about the product. At the same time, streamers should emphasize the similarity between themselves and their viewers when interacting and communicating with them and reassure them that the products they offer will meet their personal needs and group characteristics, further enhancing consumers’ sense of belonging and identity, attracting and retaining them to subscribe to the live stream and make continuous purchases.

Fourth, cultivate popular streamers and enhance the quality of products. Celebrity streamers with social influence act as streamers, forming a quality endorsement effect on the goods in the live broadcast room [

61]. Due to the significant Matthew effect in LS e-commerce, the head streamer has the bargaining power and occupies most of the resources with goods. Therefore, enterprises should tilt some resources for outstanding streamer talents and promote, market and build momentum for them to incubate popular streamers. For general sellers, they can establish a good communication and interaction mechanism with consumers in the live room, answer their questions and needs and make them feel important and cared for. In addition, stars and streamers can be invited to bring goods together in a timely manner. With their celebrity effect and influence, they can attract a large number of new audiences to visit the live broadcast room, through the consumer trust in the streamer to enhance the trust in the product, increasing the influence of the product and turnover. At the same time, the key to sustainable purchases still depends on the product, so businesses need to improve product quality, ensure product quality, accumulate good product reputation, improve consumer trust in the product and maximize the benefits of live streaming.

7. Limitations and Further Research

Our research has some limitations. Firstly, regional differences were not taken into account in this study. The impact of regional differences on consumers’ willingness to continue purchasing remains unclear; therefore, the general applicability of the conclusions of this paper deserves further investigation. Secondly, the survey sample of this study mainly consisted of young students, who are more likely to accept new forms of e-commerce, such as live-streaming e-commerce, due to their enthusiasm for online shopping. This characteristic facilitates research on live-streaming e-commerce consumption. However, consumers of different age groups may exhibit different behaviors when shopping through live streaming. Future research can consider segmenting consumers by age group to gain a more detailed understanding of their purchasing behavior. Finally, this paper regards authenticity as one aspect of perceived value, as it not only relates to consumers’ expectations and satisfaction with the product but also to their trust and recognition of the streamer and live-streaming platform. However, it can also be viewed as a value related to honesty or trust. We believe that authenticity in live-streaming e-commerce is indeed a complex issue, involving both perceived utilitarian value and perceived trust value. We will delve deeper into this issue and discuss it more comprehensively in future research.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Y.W.; Software, H.H.; Investigation, H.H.; Resources, Y.W.; Data curation, H.H.; Writing—original draft, H.H.; Writing—review & editing, Y.W.; Supervision, Y.W.; Funding acquisition, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Heilongjiang Philosophy and Social Science Fund No. 22GLE379, 2022 Harbin University of Commerce Innovation project support plan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement items.

Table A1.

Measurement items.

| Construct | Item | References |

|---|

Utilitarian value

(UV) | UV1: Sellers who sell goods through LS look like genuine merchants. | Sweeney and Soutar [37]

Chiu et al. [14]

Wongkitrunrueng and Assarunt [34] |

| UV2: Products sold via LS appear to be authentic. |

| UV3: I think that the live product is good value for money. |

| UV4: I think the promotion for that live shopping is great. |

| UV5: Compared to other ways, I think shopping through that live room is a better value and better deal. |

Hedonic value

(HV) | HV1: The process of shopping on the LS made me feel relaxed. | Sweeney and Soutar [37] |

| HV2: I enjoy live shopping. |

| HV3: I thought it was fun to shop through that live room. |

| HV4: I feel like time flies when shopping in that live room. |

| HV5: When shopping in that live room, sometimes I forget my worries. |

Social value

(SV) | SV1: By shopping live, I feel very fashionable. | Sweeney and Soutar [37]

Wongkitrunrueng and Assarunt [34] |

| SV2: Interacting on air gives me a sense of identity. |

| SV3: Shopping via LS can make a good impression on others. |

| SV4: When shopping via LS, I can find products that match my style. |

| SV5: I would love to tell my friends/acquaintances about this live shopping. |

Trust in streamer

(TS) | TS1: I believe the information provided by the streamer on air. | Gefen and Straub [50] |

| TS2: I believe the streamer is well-meaning and will consider the basic interests of the buyer. |

| TS3: I am comfortable buying the products recommended by the streamer. |

| TS4: I believe the streamer is capable of handling online transactions. |

| TS5: I believe that the products and services recommended by the streamer are useful to everyone. |

Trust in product

(TP) | TP1: I believe that the products sold in that live room are genuine. | Wongkitrunrueng and Assarunt [34] |

| TP2: I consider the quality of the products sold in this live room to be reliable. |

| TP3: I believe the product received was the same as the one demonstrated on the LS. |

| TP4: I believe I will be very happy with the product I receive. |

| TP5: I believe the products are backed by a comprehensive after-sales guarantee. |

Continuous

Purchase intention

(CPI) | CPI1: I would consider buying this product after watching the live stream. | Dodds et al. [51]

Dubinsky et al. [52] |

| CPI2: I plan to continue to follow this e-commerce live in the future. |

| CPI3: When I need it, I am willing to buy it directly from the live room. |

| CPI4: I prefer to buy the same items live. |

| CPI5: In the future I will be watching more LS e-commerce to purchase items. |

References

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, K. The Determinants of Purchase Intention on Agricultural Products via Public-Interest Live Streaming for Farmers during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Ai, M. The Impact of Self-Efficacy and Perceived Value on Customer Engagement under Live Streaming Commerce Environment. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2022, 2022, e2904447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, M.; Qiao, J. Research on the Impact of Live Broadcasting on Consumers’ Buying Behavior—Intermediate by perceived value. Price Theor. Pract. Mag. House 2021, 6, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; pp. xii, 266. ISBN 978-0-262-13090-5. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, R.; Rossiter, J. Store Atmosphere: An Environmental Psychology Approach. J. Retail. 1982, 58, 34–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Li, T.; Yang, S.; Chen, Y. What Drives Consumers’ Purchase Intention of Online Paid Knowledge? A Stimulus-Organism-Response Perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2022, 52, 101126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.O.; Sasser, W.E. Why Satisfied Customers Defect. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Eze, U.C.; Ndubisi, N.O. Analyzing Key Determinants of Online Repurchase Intentions. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2011, 23, 200–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhao, X. Empirical studies of repeat purchase intentions of online consumers based on the moderating role of habit. J. Shenyang Aerosp. Univ. 2015, 32, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.-T.; Lu, C.-C. Determinants of Success for Online Insurance Web Sites: The Contributions from System Characteristics, Product Complexity, and Trust. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2014, 24, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Xiao, J.; Jin, Y. Study on the Influencing Factors of Consumers’ Continuous Buying Intention on Social E-Commerce Platform Based on S-O-R Theory. Soft Sci. 2020, 34, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.; Newman, B.; Gross, B. Consumption Values and Market Choices: Theory and Applications. J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 487–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-M.; Wang, E.T.G.; Fang, Y.-H.; Huang, H.-Y. Understanding Customers’ Repeat Purchase Intentions in B2C e-Commerce: The Roles of Utilitarian Value, Hedonic Value and Perceived Risk. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-Y.; Lu, H.-P. Predicting Mobile Social Network Acceptance Based on Mobile Value and Social Influence. Internet Res. 2015, 25, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings, and Fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rintamäki, T.; Kanto, A.; Kuusela, H.; Spence, M. Decomposing the Value of Department Store Shopping into Utilitarian, Hedonic and Social Dimensions: Evidence from Finland. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2006, 34, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Chervany, N.L. What Trust Means in E-Commerce Customer Relationships: An Interdisciplinary Conceptual Typology. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2001, 6, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. The Establishment and Impact of Trust Relationships in Live Band Communication. Youth J. 2021, 8, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiak, S.X.; Benbasat, I. Understanding Customer Trust in Agent-Mediated Electronic Commerce, Web-Mediated Electronic Commerce, and Traditional Commerce. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2004, 5, 181–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, B. From Virtual Community Members to C2C E-Commerce Buyers: Trust in Virtual Communities and Its Effect on Consumers’ Purchase Intention. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Fan, J. Shaping Trust: The Scene Framework and Emotional Logic of Live Online E-Commerce. J. Southwest Minzu Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2021, 42, 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or Fun: Measuring Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Dhillon, G.S. Interpreting Dimensions of Consumer Trust in E-Commerce. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2003, 4, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Ge, J.; Zhou, X. Understanding Antecedents of Live Video Stream Continuance Use and Users’ Subjective Well-Being via Expectation Confirmation Model and Parasocial Relationships. J. Commun. Rev. 2020, 73, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Liu, C.; Shi, R. How Do Fresh Live Broadcast Impact Consumers’ Purchase Intention? Based on the SOR Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, R.; Oh, L.B.; Wang, K. Developing User Loyalty for Social Networking Sites: A Relational Perspective. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2016, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisstein, F.L.; Monroe, K.B.; Kukar-Kinney, M. Effects of Price Framing on Consumers’ Perceptions of Online Dynamic Pricing Practices. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, P.; Wang, G.; Zhao, Y. An Empirical Study on the Effect of Perceived Value of Retailer’s Private Label on Purchase Intention. Nanjing J. Soc. Sci. 2009, 09, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Mei, H. Empirical Research on the Decision-Making Influence Factors in Consumer Purchase Behavior of Webcasting Platform. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management, Ontario, ON, Canada, 5–8 August 2019; Xu, J., Cooke, F.L., Gen, M., Ahmed, S.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1017–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, X.; Zhang, R.; Su, Y.; Yang, Y. Exploring How Live Streaming Affects Immediate Buying Behavior and Continuous Watching Intention: A Multigroup Analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2022, 39, 109–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal-e-Hasan, S.M.; Lings, I.N.; Mortimer, G.; Neale, L. How Gratitude Influences Customer Word-Of-Mouth Intentions and Involvement: The Mediating Role of Affective Commitment. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2017, 25, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xu, Z. The Theoretical Model of Bullet Screen Users’ Participative Behavior in Network Broadcast PlatformBased on the Perspective of Flow Theory. Inf. Sci. 2017, 35, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkitrungrueng, A.; Assarut, N. The Role of Live Streaming in Building Consumer Trust and Engagement with Social Commerce Sellers. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzallah, D.; Muñoz Leiva, F.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. To Buy or Not to Buy, That Is the Question: Understanding the Determinants of the Urge to Buy Impulsively on In-stagram Commerce. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 16, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X. Exploring Consumers’ Purchase and Engagement Intention on E-Commerce Live Streaming Platform. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer Perceived Value: The Development of a Multiple Item Scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, P.; Zia, A.; Kaur, K. Social Influence in Online Retail: A Review and Research Agenda. Eur. Manag. J. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, B.U.; Peña, A.P.; Medina, C.M. The Moderating Effect of Blogger Social Influence and the Reader’s Experience on Loyalty toward the Blogger. Online Inf. Rev. 2018, 43, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.-W.; Cheng, M.-J.; Lee, C.-J. A New Mechanism for Purchasing through Personal Interactions: Fairness, Trust and Social Influence in Online Group Buying. Inf. Technol. People 2021, 35, 1563–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Liu, F.; Chen, S.; Duan, K. Can I Evoke You? A Study on the Influence Mechanism of Information Source Characteristics of Different Types of Live Broadcasting Celebrity on Consumers’ Willingness to Purchase. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2020, 23, 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Tsai, C. The Empirical Study of CRM: Consumer-company Identification and Purchase Intention in the Direct Selling Industry. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2007, 17, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, C.E.; Tannenbaum, P.H. The Principle of Congruity in the Prediction of Attitude Change. Psychol. Rev. 1955, 62, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Cao, P.; Chu, J.; Wang, H.; Wattenhofer, R. How Live Streaming Changes Shopping Decisions in E-Commerce: A Study of Live Streaming Commerce. Comput. Support. Coop. Work. 2022, 31, 701–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, C.; Jin, S. What Drives Consumer Purchasing Intention in Live Streaming E-Commerce? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 938726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Shi, Y. Research on the Influencing Mechanism of Live Broadcasting Marketing Pattern on Consumers’ Purchase Decision. China Bus. Mark. 2020, 34, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.C.-A.; Hung, S.-Y. Examination of Community Identification and Interpersonal Trust on Continuous Use Intention: Evidence from Experienced Online Community Members. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Tractinsky, N.; Vitale, M. Consumer Trust in an Internet Store. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2000, 1, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, E.K.; Sharp, B.M. Brand Awareness Effects on Consumer Decision Making for a Common, Repeat Purchase Product: A Replication. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 48, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.W. Consumer Trust in B2C E-Commerce and the Importance of Social Presence: Experiments in e-Products and e-Services. Omega 2004, 32, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of Price, Brand, and Store Information on Buyers’ Product Evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Dubinsky, A.J. A Conceptual Model of Perceived Customer Value in E-Commerce: A Preliminary Investigation. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 323–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalia, P. Service Quality Scales in Online Retail: Methodological Issues. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 630–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, Q.; Cao, Y. Understanding Consumer Online Impulse Buying in Live Streaming E-Commerce: A Stimulus-Organism-Response Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarah, S.; Sobari, N. The Effect of Live Streaming on Purchase Intention of E-Commerce Customers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Family Business and Entrepreneurship, Online, 2 June 2022; Volume 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayanto, A.N.; Ovirza, M.; Anggia, P.; Budi, N.F.A.; Phusavat, K. The Roles of Elec-tronic Word of Mouth and Information Searching in the Promotion of a New E-Commerce Strategy: A Case of Online Group Buying in Indonesia. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2017, 12, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, N. Marketing Strategies, Perceived Risks, and Consumer Trust in Online Buying Behaviour. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Gao, S.; Zhang, X. How to Use Live Streaming to Improve Consumer Purchase In-tentions: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Du, Z.; Yuan, R.; Miao, Q. Short-Term or Long-Term Cooperation between Retailer and MCN? New Launched Products Sales Strategies in Live Streaming e-Commerce. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, M.; Zheng, S.; Lin, L.; Wang, L. The Impact of Broadcasters on Consumer’s Intention to Follow Livestream Brand Community. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).