Towards Adaptive Governance of Urban Nature-Based Solutions in Europe and Latin America—A Qualitative Exploratory Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Adaptive Governance and Its Role in the Integration of NBS in the Planning Process

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis and Interpretation

- I.

- Volatile factors, which display strong driving power and very strong dependence;

- II.

- Driving factors, which have very strong driving power and very weak dependence;

- III.

- Autonomous factors, which present very weak driving power and weak dependence;

- IV.

- Dependent factors, which display very low driving power but high dependence.

4. Results

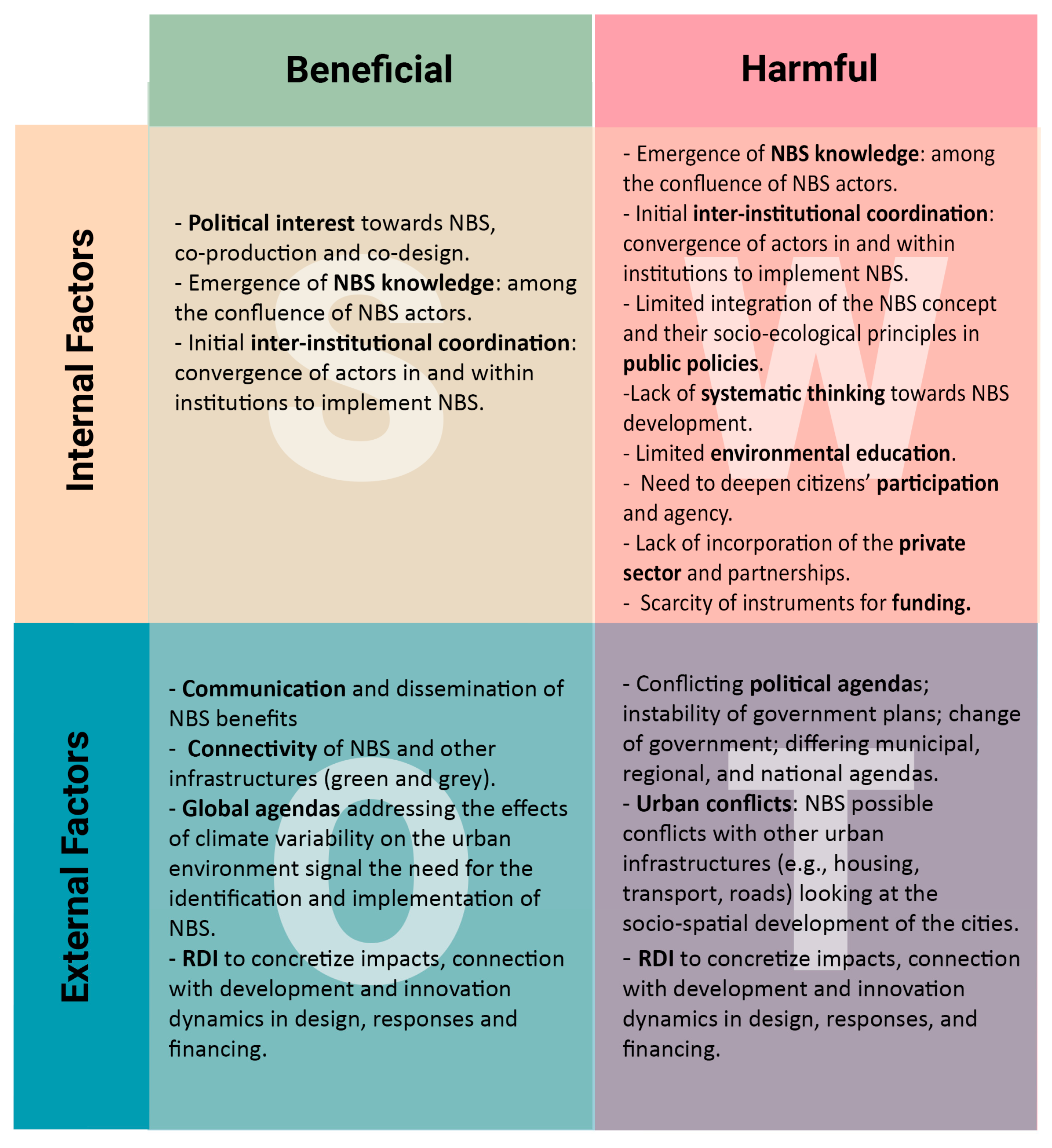

4.1. SWOT Analysis: Main Factors That Influence Urban NBS Adaptive Governance in Europe and Latin America

4.1.1. Strengths and Weaknesses: Positive and Negative Internal Factors of Urban NBS Adaptive Governance

4.1.2. Opportunities and Threats: Positive and Negative External Factors of Urban NBS Adaptive Governance

4.2. Prospective Analysis: Driving Power and Dependence of Influencing Factors of NBS Adaptive Governance

4.2.1. Quadrant I: Volatile Factors

4.2.2. Quadrant II: Driving Factors

4.2.3. Quadrant III: Autonomous Factors

4.2.4. Quadrant IV: Dependent Factors

5. Discussion

5.1. Common Pathways

5.1.1. Legal and Institutional Framework Related Factors

5.1.2. Learning and Experimentation Related Factors

5.1.3. Cooperation and Co-Management Related Factors

5.2. Singular Pathways

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| EU | LA |

|---|---|

| 1. Political agendas: political party agendas; instability of government plans; change of government; differing municipal, regional and national agendas. | 1. Political agendas: political party agendas; instability of government plans; change of government; differing municipal, regional and national agendas. |

| 2. Public policies: limited integration of the NBS concept and of socio-ecological principles and criteria for their design and implementation. | 2. Public policies: limited integration of the NBS concept and of socio-ecological principles and criteria for their design and implementation. |

| 3. Inter-institutional coordination: confluence of resources and actors in institutions to implement NBS. | 3. Inter-institutional coordination: confluence of resources and actors in institutions to implement NBS (e.g., housing and environmental management policies). |

| 4. Relation to global agendas: global agendas addressing the effects of climate variability on the urban environment signalise the need for the identification and implementation of NBS. | 4. Relation to global agendas: global agendas addressing the effects of climate variability on the urban environment signalise the need for the identification and implementation of NBS. |

| 5. NBS knowledge: facilitate the confluence of actors (people, public administration, academia, and private sector) and their knowledge. | 5. NBS Knowledge: facilitate the confluence of actors (people, public administration, academia and private sector) and their knowledge. |

| 6. Environmental education: increased knowledge about NBS and their effects on socio-ecological dynamics and urban ecology. | 6. Environmental education: increased knowledge about NBS and their effects on socio-ecological dynamics and urban ecology. |

| 7. RDI (research, development, and innovation): research to concretise impacts, connection with development and innovation dynamics in design, responses and financing. | 7. RDI (research, development, and innovation): research to concretise impacts, connection with development and innovation dynamics in design, responses and financing. |

| 8. Citizens participation and agency: deepen citizens’ participation and empowerment. | 8. Citizens participation and agency: deepen citizens’ participation and empowerment. |

| 9. Political and public interest: interest of the local population and authorities on reconnecting with nature. | 9. Demand: population’s pressure towards public institutions to obtain resources and support to solve socio-environmental issues. |

| 10. Instruments for funding: regulatory frameworks for investments to understand and enable fiscal and financial incentives and private funding. | 10. Costs: implementation costs and regulatory frameworks for investments. Fiscal and financial incentives can subsidise implementation and operating costs. |

| 11. Urban conflict & development approach: NBS possible conflicts with urban infrastructures (e.g., housing, transport, roads) looking at the socio-spatial development of the cities. | 11. Growth and urban development: consider the socio-spatial growth of the city and its management. |

| 12. Systematic thinking toward development: approach to NBS through three perspectives (social, environmental, and economic). | 12. Equity: unequal access to natural resources and environmental services between individuals or groups constitute a major issue of inequity causing a perception of conflict between NBS and social issues. |

| 13. NIMBY: trade-offs between NBS implementation and urban lifestyle can hinder NBS development. | 13. Heritage: various forms of tangible and intangible, public and private heritage linked to NBS implementation. |

| 14. Incorporation of the private sector: understand how to engage the private sector, assessing available funds and partnerships. | 14. Technology: permeates all scales and dimensions of NBS. Its availability and accessibility are fundamental for NBS dissemination and implementation. |

| 15. Connectivity: create synergies between NBS, other green infrastructures and traditional grey infrastructures of the cities. | 15. Continuity: stable support plans and programmes to maintain NBS and ensure continuity of expected services and functions. |

| 16. Communication: dissemination of NBS benefits to enable the local population to fulfil a crucial role in decisions affecting their environment. | 16. Credibility in the public sector: growing distrust caused by problems of corruption and clientelism. |

References

- UNEP. Resolution Adopted by the United Nations Environment Assembly on 2 March 2022. Nature-Based Solutions for Supporting Sustainable Development; United Nations Environment Assembly of the United Nations Environment Programme, Fifth Session, Nairobi (hybrid), 22 and 23 February 2021 and 28 February–2 March 2022; UNEP: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, C.; Schröter, B.; Haase, D.; Brillinger, M.; Henze, J.; Herrmann, S.; Gottwald, S.; Guerrero, P.; Nicolas, C.; Matzdorf, B. Addressing societal challenges through nature-based solutions: How can landscape planning and governance research contribute? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 182, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Pauleit, S.; Naumann, S.; Davis, M.; Artmann, M.; Haase, D.; Knapp, S.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; et al. Nature-based solutions to climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban areas: Perspectives on indicators, knowledge gaps, barriers, and opportunities for action. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biswal, B.K.; Bolan, N.; Zhu, Y.G.; Balasubramanian, R. Nature-based Systems (NbS) for mitigation of storm water and air pollution in urban areas: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dousari, A.M.; Ahmed, M.; Al-Dousari, N.; Al-Awadhi, S. Environmental and economic importance of native plants and green belts in controlling mobile sand and dust hazards. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 2415–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, H.M.; Kayed, M. Applying porous trees as a windbreak to lower desert dust concentration: Case study of an urban community in Dubai. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 57, 126915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; McBride, J.; Zhou, J.; Sun, Z. The urban forest in Beijing and its role in air pollution reduction. Urban For. Urban Green. 2005, 3, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, S.; Gray, T.; Ward, K. Enhancing urban nature and place-making in social housing through community gardening. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 72, 127586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, V.; Gough, W.A.; Zgela, M.; Milosevic, D.; Dunjic, J. Lowering the Temperature to Increase Heat Equity: A Multi-Scale Evaluation of Nature-Based Solutions in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, W.T.L.; Brazel, A.J. Assessing xeriscaping as a sustainable heat island mitigation approach for a desert city. Build. Environ. 2012, 47, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Navarro, C.; Pataki, D.E.; Pardyjak, E.R.; Bowling, D.R. Effects of vegetation on the spatial and temporal variation of microclimate in the urbanized Salt Lake Valley. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 296, 108211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouakou, L.M.M.; Yeo, K.; Kone, M.; Ouattara, K.; Kouakou, A.K.; Delsinne, T.; Dekoninck, W. Espaces verts comme une alternative de conservation de la biodiversité en villes: Le cas des fourmis (Hyménoptère: Formicidae) dans le district d’Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire). J. Appl. Biosci. 2018, 131, 13358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shackleton, C. Do indigenous street trees promote more biodiversity than alien ones? Evidence using mistletoes and birds in South Africa. Forests 2016, 7, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cortinovis, C.; Olsson, P.; Boke-Olén, N.; Hedlund, K. Assessing Potential for and Benefits of Scaling up Nature-Based Solutions in Malmö. In Innovation in Urban and Regional Planning; La Rosa, D., Privitera, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Inácio, M.; Karnauskaite, D.; Bogdzevič, K.; Gomes, E.; Kalinauskas, M.; Barcelo, D. Nature-Based Solutions Impact on Urban Environment Chemistry: Air, Soil, and Water. In Nature-Based Solutions for Flood Mitigation. The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry, Vol 107; Ferreira, C.S.S., Kalantari, Z., Hartmann, T., Pereira, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Gersonius, B.; Kapelan, Z.; Vojinovic, Z.; Sanchez, A. Assessing the Co-Benefits of green-blue-grey infrastructure for sustainable urban flood risk management. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 239, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Q. Rainfall interception by Santa Monica’s municipal urban forest. Urban Ecosyst. 2002, 6, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommer, J.; Bucchignani, E.; Leo, L.S.; Kalas, M.; Vranić, S.; Debele, S.; Kumar, P.; Cloke, H.L.; Di Sabatino, S. Quantifying co-benefits and disbenefits of Nature-based Solutions targeting Disaster Risk Reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Res. 2022, 75, 102966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, H.; Polasky, S.; Haight, R.G. The value of urban tree cover: A hedonic property price model in Ramsey and Dakota Counties, Minnesota, USA. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1646–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K.L. City trees and property values. Arborist News 2007, 16, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Astell-Burt, T.; Feng, X. Association of Urban Green Space with Mental Health and General Health among Adults in Australia. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e198209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, B.S.; Malecki, K.N.; Peppard, P.E.; Beyer, K.M.M. Exposure to neighborhood green space and sleep: Evidence from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin. Sleep Health 2018, 4, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abass, Z.; Tucker, R. Fifty Shades of Green: Tree coverage and neighbourhood attachment in relation to social interaction in Australian suburbs. In Fifty Years Later: Revisiting the Role of Architectural Science in Design and Practice: 50th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association; Zuo, J., Daniel, L., Soebarto, V., Eds.; The Architectural Science Association and The University of Adelaide: Adelaide, Australia, 2016; pp. 259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Holtan, M.T.; Dieterlen, S.L.; Sullivan, W.C. Social Life Under Cover: Tree Canopy and Social Capital in Baltimore, Maryland. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 502–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Towards an EU Research and Innovation policy agenda for Nature-Based Solutions & Re-Naturing Cities. Final Report of the Horizon 2020 Expert Group on ‘Nature-Based Solutions and Re-Naturing Cities’; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Amaya-Espinel, J.D.; Hernández-Garcia, J.; Cruz-Suárez, M.A. State of the Art, Good Practices and NBS Typology in European Union and Latin America Cities.Report D2.1, v1.1, 2021; European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement no. 867564. Available online: tinyurl.com/conexus-project (accessed on 22 January 2023).

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Walters, G.; Janzen, C.; Maginnis, S. Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dorst, H.; van der Jagt, A.; Raven, R.; Runhaar, H. Urban greening through nature-based solutions—Key characteristics of an emerging concept. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 49, 101620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassin, J.; Ochoa-Tocachi, B.F. Learning from indigenous and local knowledge: The deep history of nature-based solutions In Nature-Based Solutions and Water Security: An Action Agenda for the 21st Century; Cassin, J., Matthews, J.H., Lopez-Gunn, E., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 283–335. [Google Scholar]

- Tzoulas, K.; Galan, J.; Venn, S.; Dennis, M.; Pedroli, B.; Mishra, H.; Haase, D.; Pauleit, S.; Niemelä, J.; James, P. A conceptual model of the social–ecological system of nature-based solutions in urban environments. Ambio 2021, 50, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toxopeus, H.; Polzin, F. Reviewing financing barriers and strategies for urban nature-based solutions. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 112371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorst, H.; van der Jagt, A.; Toxopeus, H.; Tozer, L.; Raven, R.; Runhaar, H. What’s behind the barriers? Uncovering structural conditions working against urban nature-based solutions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 220, 104335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabi, S.E.; Han, Q.; Romme, A.G.L.; de Vries, B.; Wendling, L. Key enablers of and barriers to the uptake and implementation of Nature-based Solutions in urban settings: A review. Resources 2019, 8, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarabi, S.; Han, Q.; Romme, A.G.L.; de Vries, B.; Valkenburg, R.; den Ouden, E.; Zalokar, S.; Wendling, L. Barriers to the adoption of Urban Living Labs for NBS implementation: A systemic perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, M.; Balzan, M.; Collier, M.; Geneletti, D.; Tomaskinova, J.; Abela, R.; Borg, D.; Buhagiar, G.; Camilleri, L.; Cardona, M.; et al. Priority knowledge needs for implementing nature-based solutions in the Mediterranean islands. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 116, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Collier, M.J.; Kendal, D.; Bulkeley, H.; Dumitru, A.; Walsh, C.; Noble, K.; van Wyk, E.; Ordóñez, C.; et al. Nature-based solutions for urban climate change adaptation: Linking science, policy, and practice communities for evidence-based decision-making. Bioscience 2019, 69, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clar, C.; Prutsch, A.; Steurer, R. Barriers and guidelines for public policies on climate change adaptation: A missed opportunity of scientific knowledge-brokerage. Nat. Resour. Forum 2013, 37, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquini, L.; Cowling, R.M. Opportunities and challenges for mainstreaming ecosystem-based adaptation in local government: Evidence from the Western Cape, South Africa. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2015, 17, 1121–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesshöver, C.; Assmuth, T.; Irvine, K.; Rusch, G.; Waylen, K.; Delbaere, B.; Haase, D. The science, policy and practice of nature-based solutions: An interdisciplinary perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 579, 1215–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond, C.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Kabisch, N.; Berry, P.; Breil, M.; Razvan, M.; Geneletti, D.; Calfapietra, C. A framework for assessing and implementing the co-benefits of nature-based solutions in urban areas. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 77, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N. Seven lessons for planning nature-based solutions in cities. Environ. Sci. Policy. 2019, 93, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalzbauer, A. Barriers and Success Factors for Effectively Cocreating Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Regeneration; Deliverable 1.1.1, CLEVER Cities, H2020 Grant No. 776604; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.G.; Scolobig, A.; Linnerooth-Bayer, J.; Liu, W.; Balsiger, J. Catalyzing innovation: Governance enablers of nature-based solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, C.; Brillinger, M.; Guerrero, P.; Gottwald, S.; Henze, J.; Schmidt, S.; Ott, E.; Schröter, B. Planning nature-based solutions: Principles, steps, and insights. Ambio 2021, 50, 1446–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egusquiza, A.; Cortese, M.; Perfido, D. Mapping of innovative governance models to overcome barriers for nature-based urban regeneration. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 323, 012081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Andrade, A.; Dalton, J.; Dudley, N.; Jones, M.; Kumar, C.; Maginnis, S.; Maynard, S.; Nelson, C.S.; Renaud, F.G.; et al. Core principles for successfully implementing and upscaling Nature-based Solutions. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 98, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, T. ‘Nature-based solutions’ is the latest green jargon that means more than you might think. Nature 2017, 541, 133–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R. The Institutional Dimensions of Environmental Change: Fit, Interplay, and Scale; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, G.S.; Cumming, D.H.M.; Redman, C.L. Scale mismatches in social-ecological systems: Causes, consequences, and solutions. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FAO. Guidelines on Urban and Peri-Urban Forestry; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos, M.C.; Agrawal, A. Environmental governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2006, 31, 297–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosius, J.P.; Tsing, A.L.; Zerner, C. Communities and Conservation: Histories and Politics of Community-Based Natural Resource Management; Rowman Altamira: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin, B.C.; Gosnell, H.; Cosens, B.A. A decade of adaptive governance scholarship: Synthesis and future directions. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theor. 2007, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pauleit, S.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Andersson, E.; Anton, B.; Buijs, A.; Haase, D.; Kronenberg, J.; Mattijssen, T.; Olafsson, A.S.; Rall, E.; et al. Advancing urban green infrastructure in Europe: Outcomes and reflections from the GREEN SURGE project. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 40, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield-Dodds, S.; Nelson, R.; Cook, D.C. Adaptive governance: An introduction, an implications for public policy. In Proceedings of the ANZSEE Conference, Noosa, Australia, 4–5 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cleaver, F.; Whaley, L. Understanding process, power, and meaning in adaptive governance: A critical institutional reading. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morris, M.; de Loe, R.C. Cooperative and adaptive transboundary water governance in Canada’s Mackenzie River Basin: Status and prospects. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGinnis, M.D.; Ostrom, E. Social-ecological system framework: Initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huitema, D.; Mostert, E.; Egas, W.; Moellenkamp, S.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Yalcin, R. Adaptive water governance: Assessing the institutional prescriptions of adaptive (co-)management from a governance perspective and defining a research agenda. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö.; Crona, B.I. The role of social networks in natural resource governance: What relational patterns make a difference? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive Governance of Social-Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toxopeus, H.; Kotsila, P.; Conde, M.; Katona, A.; van der Jagt, A.P.N.; Polzin, F. How ‘just’ is hybrid governance of urban nature-based solutions? Cities 2020, 105, 102839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffin, B.C.; Garmestani, A.S.; Gunderson, L.H.; Benson, M.H.; Angeler, D.G.; Arnold, C.A.; Cosens, B.; Craig, R.K.; Ruhl, J.B.; Allen, C.R. Transformative Environmental Governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, M.; van der Voort, H. Agile and adaptive governance in crisis response: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westskog, H.; Amundsen, H.; Christiansen, P.; Tønnesen, A. Urban contractual agreements as an adaptive governance strategy: Under what conditions do they work in multi-level cooperation? J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2020, 22, 554–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Jagt, A.P.N.; Kiss, B.; Hirose, S.; Takahashi, W. Nature-Based Solutions or Debacles? The Politics of Reflexive Governance for Sustainable and Just Cities. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 2, 583833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, G.A.; Greve, C. Public–private partnerships: An international performance review. Public Admin. Rev. 2007, 67, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, J.; Fraser, I.; McGarvey, N. Transparency of risk and reward in U.K. public–private partnerships. Public Budg. Financ. 2006, 26, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budds, J.; Hinojosa, L. Restructuring and rescaling water governance in mining contexts: The co-production of waterscapes in Peru. Water Altern. 2012, 5, 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Knieper, C. The capacity of water governance to deal with the climate change adaptation challenge: Using fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis to distinguish between polycentric, fragmented and centralized regimes. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 29, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Social–ecological systems and adaptive governance of the commons. Ecol. Res. 2007, 22, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittilson, M.C.; Schwindt-Bayer, L. Engaging Citizens: The Role of Power-Sharing Institutions. J. Politics 2010, 72, 990–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, A.J. Negotiation, Meet New Governance: Interests, Skills, and Selves. Law Soc. Inq. 2008, 33, 503–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Gibson, C.C. Enchantment and disenchantment: The role of community in natural resource conservation. World Dev. 1999, 27, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D. Governance and the commons in a multi-level world. Int. J. Commons 2007, 2, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D.; Berkes, F.; Doubleday, N. Adaptive Comanagement: Collaboration, Learning, and Multi-Level Governance; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Slocum, N. Participatory Methods Toolkit: A Practitioner’s Manual; UNU/CRIS: Brugge, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, D.; Bammer, G.; Deane, P. Research Integration Using Dialogue Methods; ANU E Press: Canberra, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Reguant Álvarez, M.; Torrado-Fonseca, M. El mètode Delphi. REIRE—Revista d’Innovació I Recerca En Educació 2016, 9, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hasson, F.; Keeney, S.; McKenna, H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 32, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Attri, R.; Dev, N.; Sharma, V. Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM) approach: An Overview. Res. J. Manag. Sci. 2013, 2, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Godet, M. From Anticipation to Action. A Handbook of Strategic Prospective; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Godet, M. How to be rigorous with scenario planning. Foresight 2000, 2, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godet, M. Creating Futures: Scenario Planning as a Strategic Management Tool; Economica: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas, M.L.; Wilde, V.; Hagen-Zanker, A.; Seifert-Dähnn, I.; Hutchins, M.G.; Loiselle, S. The circular benefits of participation in nature-based solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulsrud, N.M.; Hertzog, K.; Shears, I. Innovative urban forestry governance in Melbourne?: Investigating “green placemaking” as a nature-based solution. Environ. Res. 2018, 161, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallopín, G.C. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Wandel, J. Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Sendzimir, J.; Jeffrey, P.; Aerts, J.; Bergkamp, G.; Cross, K. Managing change toward adaptive water management through social learning. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniga-Teran, A.A.; Staddon, C.; de Vito, L.; Gerlak, A.K.; Ward, S.; Schoeman, Y.; Hart, A.; Booth, G. Challenges of mainstreaming green infrastructure in built environment professions. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 63, 710–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabi, S.; Han, Q.; Romme, A.G.L.; de Vries, B.; Valkenburg, R.; den Ouden, E. Uptake and implementation of Nature-Based Solutions: An analysis of barriers using Interpretive Structural Modeling. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 270, 110749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Naumann, S. Making the Case for Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems as a Nature-Based Solution to Urban Flooding. In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice; Kabisch, N., Korn, H., Stadler, J., Bonn, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, I.; Morello, E. Co-creation Pathway for Urban Nature-Based Solutions: Testing a Shared-Governance Approach in Three Cities and Nine Action Labs. In Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions. Green Energy and Technology; Bisello, A., Vettorato, D., Ludlow, D., Baranzelli, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timboe, I.; Pharr, K. Chapter 7—Nature-based solutions in international policy instruments. In Nature-Based Solutions and Water Security. An Action Agenda for the 21st Century; Cassin, J., Matthews, J.H., Gunn, E., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, J.; Egerer, M.; Nuttman, S.; Keniger, L.; Pettitt, P.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Gray, T.; Ossola, A.; Lin, B.; Bailey, A.; et al. Urban agriculture as a nature-based solution to address socio-ecological challenges in Australian cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 60, 127059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, S.; Pluchinotta, I.; Pagano, A.; Pengal, P.; Cokan, B.; Giordano, R. Assessing stakeholders’ risk perception to promote Nature Based Solutions as flood protection strategies: The case of the Glinščica river (Slovenia). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupp, G.; Zingraff-Hamed, A.; Huang, J.J.; Oen, A.; Pauleit, S. Living labs—A concept for co-designing nature-base solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, C.; Clarke, L.; Carnelli, F.; Uttley, C.; Smith, B. Capturing the multiple benefits associated with nature-based solutions: Lessons from a natural flood management project in the Cotswolds, UK. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontee, N.; Narayan, S.; Beck, M.W.; Hosking, A.H. Nature-based solutions: Lessons from around the world. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Marit. Eng. 2016, 169, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Lafortezza, R. Transitional path to the adoption of nature-based solutions. Land Use Policy 2019, 80, 406–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; He, B.; Nover, D.; Lu, H.; Liu, J.; Sun, W.; Chen, W. Farm ponds in southern China: Challenges and solutions for conserving a neglected wetland ecosystem. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 1322–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlati, A.; Rödl, A.; Kanjaria-Christian, S.; Knieling, J. Stakeholder Participation in the Planning and Design of Nature-Based Solutions. Insights from CLEVER Cities Project in Hamburg. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Borgström, S.; Gorissen, L.; Egermann, M.; Ehnert, F. Nature-Based Solutions Accelerating Urban Sustainability Transitions in Cities: Lessons from Dresden, Genk and Stockholm Cities. In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice; Kabisch, N., Korn, H., Stadler, J., Bonn, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wamsler, C. Mainstreaming ecosystem-based adaptation: Transformation toward sustainability in urban governance and planning. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Droste, N.; Schröter-Schlaack, C.; Hansjürgens, B.; Zimmermann, H. Implementing Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Areas: Financing and Governance Aspects. In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice; Kabisch, N., Korn, H., Stadler, J., Bonn, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 307–321. [Google Scholar]

- Puskás, N.; Abunnasr, Y.; Naalbandian, S. Assessing deeper levels of participation in nature-based solutions in urban landscapes—A literature review of real-world cases. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 210, 104065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojvodíková, B.; Tichá, I.; Starzewska-Sikorska, A. Implementing Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Spaces in the Context of the Sense of Danger That Citizens May Feel. Land 2022, 11, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ham, C.; Klimmek, H. Partnerships for Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Areas—Showcasing Successful Examples. In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice; Kabisch, N., Korn, H., Stadler, J., Bonn, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 275–289. [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça, R.; Roebeling, P.; Fidélis, T.; Saraiva, M. Policy Instruments to Encourage the Adoption of Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Landscapes. Resources 2021, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Dong, T.; Xu, G.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y. Geographic micro-process model: Understanding global urban expansion from a process-oriented view. Comput. Environ. Urban 2021, 87, 101603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inostroza, L.; Baur, R.; Csaplovics, E. Urban Sprawl and Fragmentation in Latin America: A comparison with European Cities. The Myth of the Diffuse Latin American City; Working Paper; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Rubi, M.; Hack, J. Co-design of experimental nature-based solutions for decentralized dry-weather runoff treatment retrofitted in a densely urbanized area in Central America. Ambio 2021, 50, 1498–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruíz, A.G.; Hes, E.; Schwartz, K. Shifting Governance Modes in Wetland Management: A Case Study of Two Wetlands in Bogotá, Colombia. Environ. Plan. C 2011, 29, 990–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, L.; Parikh, P.; Dodman, D.; Alencar, J.; Scarati Martins, J.R. Problematizing infrastructural “fixes”: Critical perspectives on technocratic approaches to Green Infrastructure. Urban Geogr. 2022. [CrossRef]

| Europe | Latin America | |

|---|---|---|

| Delphi Method | 18 | 24 |

| Expert Interviews | 9 | 34 |

| Total | 27 | 58 |

| Level of Influence |

|---|

| 0—No direct influence |

| 1—Low direct influence |

| 2—Medium direct influence |

| 3—High direct influence |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kauark-Fontes, B.; Ortiz-Guerrero, C.E.; Marchetti, L.; Hernández-Garcia, J.; Salbitano, F. Towards Adaptive Governance of Urban Nature-Based Solutions in Europe and Latin America—A Qualitative Exploratory Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054479

Kauark-Fontes B, Ortiz-Guerrero CE, Marchetti L, Hernández-Garcia J, Salbitano F. Towards Adaptive Governance of Urban Nature-Based Solutions in Europe and Latin America—A Qualitative Exploratory Study. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054479

Chicago/Turabian StyleKauark-Fontes, Beatriz, César E. Ortiz-Guerrero, Livia Marchetti, Jaime Hernández-Garcia, and Fabio Salbitano. 2023. "Towards Adaptive Governance of Urban Nature-Based Solutions in Europe and Latin America—A Qualitative Exploratory Study" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054479