The Influence of Individual Cultural Value Differences on Pro-Environmental Behavior among International Students at Korean Universities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

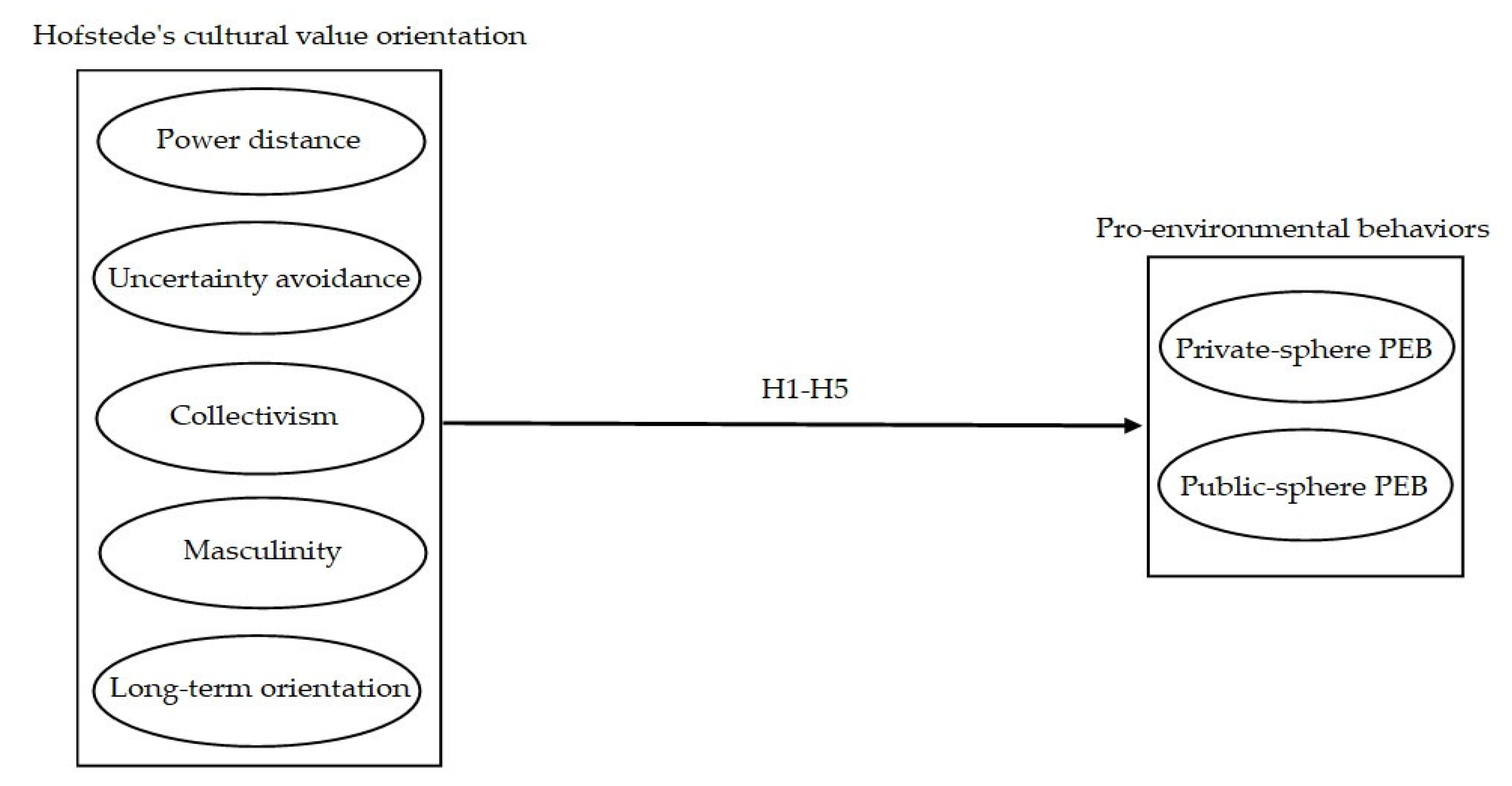

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Cultural Values and PEB

2.2. Power Distance

2.3. Individualism versus Collectivism

2.4. Masculinity versus Femininity

2.5. Uncertainty Avoidance

2.6. Long-Term Orientation versus Short-Term Orientation

3. Materials and Methods

Measurement

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amit Kumar, G. Framing a model for green buying behavior of Indian consumers: From the lenses of the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espeland, E.K.; Kettenring, K.M. Strategic plant choices can alleviate climate change impacts: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 222, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. The Sustainability Pyramid: A Hierarchical Approach to Greater Sustainability and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals with Implications for Marketing Theory, Practice, and Public Policy. Australas. Mark. J. 2022, 30, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkargkavouzi, A.; Halkos, G.; Matsiori, S. How do motives and knowledge relate to intention to perform environmental behavior? Assessing the mediating role of constraints. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 165, 106394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Teng, M.; Han, C. How does environmental knowledge translate into pro-environmental behaviors?: The mediating role of environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergek, A.; Mignon, I. Motives to adopt renewable electricity technologies: Evidence from Sweden. Energy Policy 2017, 106, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karimi, S.; Liobikienė, G.; Saadi, H.; Sepahvand, F. The Influence of Media Usage on Iranian Students’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors: An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. Contextual and psychological factors shaping evaluations and acceptability of energy alternatives: Integrated review and research agenda. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 35, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmi, N.; Arnon, S.; Orion, N. Transforming Environmental Knowledge Into Behavior: The Mediating Role of Environmental Emotions. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 46, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zou, Y.; Wu, J. Factors Influencing Public-Sphere Pro-Environmental Behavior among Mongolian College Students: A Test of Value–Belief–Norm Theory. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stern, P.C. New Environmental Theories: Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.-G.; Jeong, S.; Choi, Y. Moderating Effects of Trust on Environmentally Significant Behavior in Korea. Sustainability 2017, 9, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mi, L.; Qiao, L.; Xu, T.; Gan, X.; Yang, H.; Zhao, J.; Qiao, Y.; Hou, J. Promoting sustainable development: The impact of differences in cultural values on residents’ pro-environmental behaviors. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1539–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Gu, J. Exploring the role of cultural individualism and collectivism on public acceptance of nuclear energy. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, B.; Enkawa, T.; Schvaneveldt, S.J. The role of individualism vs. collectivism in the formation of repurchase intent: A cross-industry comparison of the effects of cultural and personal values. J. Econ. Psychol. 2015, 51, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Van Petegem, P. A Cross-Cultural Study of Environmental Values and Their Effect on the Environmental Behavior of Children. Environ. Behav. 2013, 45, 551–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyez, K. How national cultural values affect pro-environmental consumer behavior. Int. Mark. Rev. 2012, 29, 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.-N.; Thyroff, A.; Rapert, M.I.; Park, S.-Y.; Lee, H.J. To be or not to be green: Exploring individualism and collectivism as antecedents of environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.A.; Shrum, L.J. The Influence of Individualism, Collectivism, and Locus of Control on Environmental Beliefs and Behavior. J. Public Policy Mark. 2001, 20, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van de Vliert, E.; Huang, X.; Levine, R.V. National Wealth and Thermal Climate as Predictors of Motives for Volunteer Work. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 2004, 35, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morren, M.; Grinstein, A. Explaining environmental behavior across borders: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 47, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McSweeney, B. Hofstede’s Model of National Cultural Differences and their Consequences: A Triumph of Faith—A Failure of Analysis. Hum. Relat. 2002, 55, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taras, V.; Kirkman, B.L.; Steel, P. Examining the impact of Culture’s consequences: A three-decade, multilevel, meta-analytic review of Hofstede’s cultural value dimensions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 405–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nagy, S.; Konyha Molnárné, C. The Effects of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions on Pro-Environmental Behaviour: How Culture Influences Environmentally Conscious Behaviour. Theory, Methodol. Pract. 2018, 14, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Beyond individualism/collectivism: New cultural dimensions of values. In Individualism and Collectivism: Theory, Method, and Applications; Cross-cultural research and methodology series; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; Volume 18, pp. 85–119. [Google Scholar]

- Tyers, R.; Berchoux, T.; Xiang, K.; Yao, X.Y. China-to-UK Student Migration and Pro-environmental Behaviour Change: A Social Practice Perspective. Sociol. Res. Online 2019, 24, 575–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett III, C. International Student Engagement: Strategies for Creating Inclusive, Connected, and Purposeful Campus Environments. J. Int. Stud. 2016, 6, 1076–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyers, R. Barriers to enduring pro-environmental behaviour change among Chinese students returning home from the UK: A social practice perspective. Environ. Sociol. 2021, 7, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.-T.; Lin, H.-C. Sustainable Development: The Effects of Social Normative Beliefs On Environmental Behaviour. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. Who will be more active in sustainable consumption? Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 6, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Li, L.M.W. The relationship of environmental concern with public and private pro-environmental behaviours: A pre-registered meta-analysis. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 53, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Long, R.; Yue, T. Who contributed to “corporation green” in China? A view of public- and private-sphere pro-environmental behavior among employees. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 120, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyapong, J. Factors Affecting Environmental Activism, Nonactivist Behaviors, and the Private Sphere Green Behaviors of Thai University Students. Educ. Urban Soc. 2019, 52, 619–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, M.D.; Givens, J.E.; Hazboun, S.O.; Krannich, R.S. At home, in public, and in between: Gender differences in public, private and transportation pro-environmental behaviors in the US Intermountain West. Environ. Sociol. 2019, 5, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arco, M.; Marino, V. Environmental citizenship behavior and sustainability apps: An empirical investigation. Transform. Gov. People, Process Policy 2022, 16, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Lu, C.; Wei, Z. Effects of Social Capital on Pro-Environmental Behaviors in Chinese Residents. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Li, M.; Liao, Y. Trust, Identity, and Public-Sphere Pro-environmental Behavior in China: An Extended Attitude-Behavior-Context Theory. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 919578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Poškus, M.S. The Importance of Environmental Knowledge for Private and Public Sphere Pro-Environmental Behavior: Modifying the Value-Belief-Norm Theory. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agyeman, J.; Bullard, R.D.; Evans, B. Just Sustainabilities: Development in an Unequal World; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, E.U.; Stern, P.C. Public understanding of climate change in the United States. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higueras-Castillo, E.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.J.; Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Molinillo, S. The role of collectivism in modeling the adoption of renewable energies: A cross-cultural approach. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 2143–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.E.M. The role of national culture in international marketing research. Int. Mark. Rev. 2001, 18, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980; p. 475. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Geert, H.; Jan, H.G.; Michael, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, E.S.; Burke, R.J. Predictor of Business Students’ Attitudes Toward Sustainable Business Practices. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezel, E.; Ugural, M.; Giritli, H. Pro-environmental Behavior of University Students: Influence of Cultural Differences. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Filimonau, V.; Matute, J.; Mika, M.; Faracik, R. National culture as a driver of pro-environmental attitudes and behavioural intentions in tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1804–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Filimonau, V. The effect of national culture on pro-environmental behavioural intentions of tourists in the UK and China. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, I.; Abdul-Rashid, S.H.; Md Dawal, S.Z.; Aoyama, H.; Sakundarini, N.; Ho, F.H.; Herawan, S.G. Green product preferences considering cultural influences: A comparison study between Malaysia and Indonesia. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2021, 32, 1040–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruanguttamanun, C. How consumers in different cultural backgrounds prefer advertising in green ads through Hofstede’s cultural lens? A cross-cultural study. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, N.; Verma, D.; Kumar, D. Evolution and trends in consumer behaviour: Insights from Journal of Consumer Behaviour. J. Consum. Behav. 2023, 22, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmi, N.; Arnon, S. The Role of Future Orientation in Environmental Behavior: Analyzing the Relationship on the Individual and Cultural Levels. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2014, 27, 1304–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Li, L.M.W. The Mediating Role of Self-Enhancement Value on the Relationship of Power Distance and Individualism with Pro-Environmental Attitudes: Evidence from Multilevel Mediation Analysis with 52 Societies. Cross-Cultural Res. 2022, 56, 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A.; Ayoko, O.B.; Amoo, N.; Menke, C. The relationship between cultural values, cultural intelligence and negotiation styles. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Russell, C.; Lee, J. National culture and environmental sustainability: A cross-national analysis. J. Econ. Financ. 2007, 31, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W. Culture and Ecology: A Cross-National Study of the Determinants of Environmental Sustainability. Manag. Int. Rev. 2005, 45, 349–371. [Google Scholar]

- Green, E.G.T.; Deschamps, J.C.; Páez, D. Variation of individualism and collectivism within and between 20 countries: A typological analysis. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 2005, 36, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- House, R.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Javidan, M.; Dorfman, P.W.; Gupta, V. Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P. Measuring personal cultural orientations: Scale development and validation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2009, 38, 787–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Segev, S. Cultural orientations and environmental sustainability in households: A comparative analysis of Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites in the United States. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling-Yee, L. Effect of Collectivist Orientation and Ecological Attitude on Actual Environmental Commitment. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 1997, 9, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, R.S.; Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.K.; Lau, L.B.Y. Antecedents of green purchases: A survey in China. J. Consum. Mark. 2000, 17, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.P.; Swanson, D.L.; Nelson, L.K. Culture-Based Expectations Of Corporate Citizenship: A Propositional Framework And Comparison Of Four Cultures. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2001, 9, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. A hierarchical analysis of the green consciousness of the Egyptian consumer. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 445–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kals, E.; Schumacher, D.; Montada, L. Emotional affinity toward nature as a motivational basis to protect nature. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Gender differences in Hong Kong adolescent consumers’ green purchasing behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2009, 26, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ho, F.N.; Wang, H.-M.D.; Vitell, S.J. A Global Analysis of Corporate Social Performance: The Effects of Cultural and Geographic Environments. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parboteeah, K.P.; Addae, H.M.; Cullen, J.B. Propensity to Support Sustainability Initiatives: A Cross-National Model. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dustmann, C. Return migration, uncertainty and precautionary savings. J. Dev. Econ. 1997, 52, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkanasy, N.; Gupta, V.; Mayfield, M.; Trevor-Roberts, E. Future Orientation. In Culture, Leadership and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 282–342. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne, W.; Pickett, G. How materialism affects environmental beliefs, concern, and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J. Transformative green marketing: Impediments and opportunities. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Leonidou, C.N.; Kvasova, O. Antecedents and outcomes of consumer environmentally friendly attitudes and behaviour. J. Mark. Manag. 2010, 26, 1319–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joireman, J.A.; Van Lange, P.A.M.; Van Vugt, M. Who cares about the environmental impact of cars?: Those with an eye toward the future. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. History, lessons, and ways forward from the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Qual. Innov. 2021, 5, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- KOSIS KOrean Statistical Information Service. Available online: https://kosis.kr/eng/ (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N.; Lenartowicz, T. Measuring hofstede’s five dimensions of cultural values at the individual level: Development and validation of CVSCALE. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2011, 23, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliff, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 5, pp. 207–2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Jr.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis a Global Perspective; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2010; Volume 7458. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Irawan; Elia, A.; Benius. Interactive effects of citizen trust and cultural values on pro-environmental behaviors: A time-lag study from Indonesia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Lobo, A.; Greenland, S. The influence of cultural values on green purchase behaviour. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2017, 35, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, K.; Grolleau, G.; Ibanez, L. Social Norms and Pro-environmental Behavior: A Review of the Evidence. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 140, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tong, Y.; Ye, F.; Song, J. The choice of the government green subsidy scheme: Innovation subsidy vs. product subsidy. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 4932–4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Zhou, G. Willingness to pay a price premium for energy-saving appliances: Role of perceived value and energy efficiency labeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 103 | 46 |

| Male | 121 | 54 |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 112 | 50 |

| 25–34 | 105 | 46.9 |

| 35–44 | 6 | 2.7 |

| 45–54 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Education | ||

| Bachelor’s | 139 | 62.1 |

| Master’s | 60 | 26.8 |

| Doctoral | 25 | 11.2 |

| Fit Indices | CMIN/DF | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended value | 1–3 | >0.90 | >0.90 | <0.08 | <0.06 |

| Revised Model | 1.450 | 0.967 | 0.961 | 0.053 | 0.045 |

| Factors | Indicators | SFLs | CR | AVE | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power distance | PD1 | 0.731 | 0.863 | 0.679 | 0.858 |

| PD2 | 0.843 | ||||

| PD3 | 0.891 | ||||

| Collectivism | CO2 | 0.774 | 0.802 | 0.574 | 0.801 |

| CO3 | 0.780 | ||||

| CO4 | 0.717 | ||||

| Masculinity | MA1 | 0.836 | 0.879 | 0.709 | 0.875 |

| MA2 | 0.907 | ||||

| MA3 | 0.777 | ||||

| Uncertainty avoidance | UA1 | 0.694 | 0.876 | 0.640 | 0.872 |

| UA2 | 0.879 | ||||

| UA3 | 0.838 | ||||

| UA4 | 0.778 | ||||

| Long-term orientation | LO1 | 0.750 | 0.792 | 0.560 | 0.787 |

| LO2 | 0.714 | ||||

| LO3 | 0.779 | ||||

| Private-sphere PEB | RFW | 0.648 | 0.847 | 0.584 | 0.846 |

| DP | 0.823 | ||||

| BEF | 0.877 | ||||

| WS | 0.684 | ||||

| Public-sphere PEB | EC | 0.884 | 0.933 | 0.777 | 0.933 |

| RP | 0.879 | ||||

| GD | 0.902 | ||||

| ED | 0.861 |

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Power distance | |||||||

| 2 | Uncertainty avoidance | 0.398 | ||||||

| 3 | Collectivism | 0.206 | 0.498 | |||||

| 4 | Masculinity | 0.603 | 0.330 | 0.145 | ||||

| 5 | Long-term orientation | 0.350 | 0.695 | 0.684 | 0.253 | |||

| 6 | Private-sphere PEB | 0.264 | 0.417 | 0.560 | 0.216 | 0.402 | ||

| 7 | Public-sphere PEB | 0.259 | 0.365 | 0.555 | 0.291 | 0.331 | 0.631 |

| Hypothesized Relationships | Estimate | β | S.E. | t-Value | p | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Power distance→Private-sphere PEB | −0.053 | −0.068 | 0.075 | −0.712 | 0.477 | Reject |

| H2a | Uncertainty avoidance→Private-sphere PEB | 0.357 | 0.322 | 0.124 | 2.882 | 0.004 | Accept |

| H3a | Collectivism→Private-sphere PEB | 0.990 | 0.914 | 0.160 | 6.197 | *** | Accept |

| H4a | Masculinity→Private-sphere PEB | −0.069 | −0.076 | 0.082 | −0.849 | 0.396 | Reject |

| H5a | Long-term orientation→Private-sphere PEB | 0.669 | 0.596 | 0.195 | 3.437 | *** | Accept |

| H1b | Power distance→Public-sphere PEB | −0.035 | −0.029 | 0.113 | −0.313 | 0.755 | Reject |

| H2b | Uncertainty avoidance→Public-sphere PEB | 0.447 | 0.259 | 0.186 | 2.404 | 0.016 | Accept |

| H3b | Collectivism→Public-sphere PEB | 1.572 | 0.936 | 0.245 | 6.409 | *** | Accept |

| H4b | Masculinity→Public-sphere PEB | −0.308 | −0.219 | 0.124 | −2.481 | 0.013 | Accept |

| H5b | Long-term orientation→Public-sphere PEB | 1.106 | 0.636 | 0.30 | 3.686 | *** | Accept |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Riaz, W.; Gul, S.; Lee, Y. The Influence of Individual Cultural Value Differences on Pro-Environmental Behavior among International Students at Korean Universities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4490. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054490

Riaz W, Gul S, Lee Y. The Influence of Individual Cultural Value Differences on Pro-Environmental Behavior among International Students at Korean Universities. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4490. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054490

Chicago/Turabian StyleRiaz, Waqas, Sehrish Gul, and Yoonseock Lee. 2023. "The Influence of Individual Cultural Value Differences on Pro-Environmental Behavior among International Students at Korean Universities" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4490. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054490