1. Introduction

Industrial SMEs have contributed to both developed and developing economies’ social and economic prosperity. However, they are currently at a critical junction because global disturbances, ranging from geopolitical to socioeconomic, are having a major impact on the state of global manufacturing systems and causing an extraordinary change in the entire value chain [

1]. To remain competitive and manage this growing international context, businesses and governments alike must continually collaborate to reassess and reinvent industrial strategies that promote sustainable productivity, innovation and economic expansion [

1].

The War between Russia and Ukraine and the closure policies during COVID-19 have had a major effect on economic transaction globally since the rise in energy prices and the decline in investor confidence and the stability of the financial markets [

2,

3]; this has led to a big rise in the cost of buying fuel, electricity, shipping transactions and raw material, which has pushed governments and businesses to search for alternative energy sources such as wind-to-energy, waste-to-energy and solar power [

4]. Therefore, it is a challenge for industries to stay profitable and gain competitive advantages if they do not adopt flexible strategies to cope with the changing dynamics and encounter unexpected turbulences [

5].

Similarly, the company’s strategy must be highly flexible and revised continually to keep the firm successful in the short and long term. Hence, companies that can provide genuine greater value to the client through a creative strategy built on a feasible and sustainable foundation will survive for a longer period than others [

6,

7]. In the same context, the consequences of the COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020 and 2021 have forced the closure of thousands of SMEs worldwide, causing a rearrangement of the local and international economies [

8]. Therefore, SMEs should implement flexible and creative modern business strategies to achieve sustainability [

9,

10,

11].

Furthermore, competent human capital (CHC) has become one of the primary determinants of a firm’s ability to establish and maintain a competitive advantage and sustainable performance [

12,

13]. Therefore, talented human resources can create novel goods, explore inventive methods to reduce production costs, and enhance service quality. Additionally, they can establish enduring relations with shareholders [

14]. Investment in “human resources” and “sustainable innovation” should be the primary drivers at the firm level to refine commercial and financial consequences [

15].

Frequently, firms face external influences beyond their control, which are complicated to manage and which may not be removed completely from the company itself [

16]. Moreover, rapidly changing business environments are frequently defined by the attributes of their surrounding environment, including market instability, technological innovation, competitiveness and the overall economic climate [

17]. Several researchers have generally agreed that a turbulent environment influences the sustainability of firms both domestically and overseas [

18]. Therefore, the executives of different companies need coaching in dealing with turbulent circumstances to improve their firms’ performance. In addition, firms operating in dynamic environments must embrace a much less centralized and more flexible structure [

19].

Due to the difficulties posed by the old techniques of conventional manufacturing procedures adopted by industrialists, sustainability has become an important focus in modern production sectors. In this sense, sustainability in industries is defined as producing low cost-impact, environmentally friendly and socially secure goods [

20]. Therefore, SMEs in the industrial sector should adopt the concept of sustainability in order to stay competitive.

The Palestinian manufacturing SMEs are struggling with various difficulties that impede their potential to prosper and reach a higher degree of desired sustainable performance: First, significant issues are associated with external political turbulence, which limits the growth of the national economy [

21]. The second challenge is seen as a structural problem caused by the inability of Palestinian policymakers to create an attractive enabling business environment that could support a strong private sector, specifically the industrial sector [

22,

23,

24]. The third crucial challenge is that the SMEs have several managerial issues. For example, there is a lack of organizational guiding principles at the firm level, including the absence of effective strategic planning and quality systems and the lack of highly qualified human capital [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

Prior studies of the Palestinian manufacturing industry showed that locally produced products do not constitute more than 20% of the domestic market [

31]. Similarly, the SMEs are operating at 50% of their production capacity [

24,

32,

33]. In the same way, imports put a lot of pressure on manufacturing firms, which has led to a deficit in trade of around USD 5.5 billion in the country [

34]. Additionally, there is an absence of vision, policies and standard working procedures (SOPs) at the firm level [

25,

35].

Moreover, since the second uprising (the Intifada) in 2000, the political situation in Palestine has set it aside from other developing countries; the economy has been experiencing excessively high unemployment rates [

24]. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO) standard’s recent report published in 2022, economic growth in Palestine has started to recover but is projected to slow down before returning to pre-pandemic levels in 2023. Hence, employment creation lags behind growth, while poverty is still rising. Unemployment increased and peaked at 26 percent in 2021, while labor underutilization stood at 34 percent. These overall figures hide significant differences. In Gaza, for example, unemployment reached 47 percent, compared to 16 percent in the West Bank. Three out of four young graduates in Gaza were unemployed in 2021 [

36]. In this regard, the government of Palestine emphasized the important role of the industrial sector in the country in creating new opportunities and considered it a vital productive sector since it contained 13.7% of the total workforce, i.e., around 113,000 workers by 2018, which increased to 128,000 by 2020 [

31,

34]. Consequently, focusing on the enhancement of the enabling environment of the industrial sector at the policy level would contribute more actively to providing more job opportunities and minimizing poverty in Palestine. In this regard, intensive and regular dialogue between the government and private-sector stakeholders such as the Palestine Federation of Industries, the Federation of Palestinian Chambers of Commerce, Industry and Agriculture, Palestine Trade Center, etc., is highly recommended; this dialogue needs to direct the active international fund and support agencies in the country such as United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and German International Cooperation (GIZ), which have extensive global experience in the sustainability of the industrial sector, to design and develop programs to be implemented in Palestine to contribute to achieving this objective.

The aforementioned severe constraints hinder the Palestinian SMEs’ growth, competition and survival. Due to these challenges, SMEs struggle to operate efficiently and sustainably. Therefore, this study suggests that tackling most of the revealed problems and achieving an advanced level of economic, environmental and social sustainable performance in manufacturing SMEs in the country could be achieved by executing a proper analysis of the turbulent environment, implementing strategic flexibility and assuring competent human capital. Therefore, in Palestine, several issues SMEs face can be categorized and fixed using the following three managerial variables: turbulent environment, competent human capital and strategic flexibility.

Generally, SMEs have managed less formally than corporations; hence the turbulent environment, competent human capital and strategic flexibility have not been addressed with so much care. There have only been a few empirical research studies that have identified a link between various components of the turbulent environment, competent human capital and strategic flexibility, and the enhanced performance of SMEs, which ultimately leads to the sustainability of SMEs [

37,

38,

39]. Subsequently, the objective of this study is to examine the impact of the turbulent environment (TE), competent human capital (CHC) and strategic flexibility (SF) on sustainable performance (SP). The results of this research could be helpful to industrial SMEs existing in turbulent situations to encounter challenges to improve their sustainability. Likewise, it might support the legislators in Palestine to develop techniques to enhance the analysis of the turbulent environment, adapt flexible strategic planning in business and enhance the competencies of the SMEs’ human capital, such as its creative abilities, which are the key to sustained success and enduring sustainable performance. The results of this study add to the current body of relevant literature by shedding light on the topic of sustainable performance in small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) in less-developing countries with political and economic instability. Therefore, the findings from this study highlight the fact that (TE), (CHC) and (SF) are all critical management tools for firms in today’s competitive and uncertain market environment.

This study aims to fill the gap in industry and the literature by applying the theories of TBL, CT and NRBV to an investigation of the research problem. The literature review explains various theoretical frameworks that can be used to address the research problem. The study finds that CHC, SF and TE are critical management techniques for manufacturing SMEs in highly dynamic and competitive contexts.

This study differs from past research as it focuses on the interrelationship between CHC, SF, TE and SP in underdeveloped economies, particularly in an area facing political and economic turbulence. Furthermore, unlike previous studies that mainly measure profitability ratios, this study includes financial and non-financial metrics, such as social and environmental indicators, to measure Sustainable Performance in SME manufacturing industries.

The next sections of the article are ordered in the following manner. A theoretical review of the related prior studies covered in the literature, encompassing underpinning theories, the variables of the study and conceptions, is provided in

Section 2. A methodological outline of the techniques employed to gather and evaluate data is given in

Section 3. The findings of the research are outlined in

Section 4.

Section 5 deliberates the results of this study in relation to prior related studies. The recommendations and conclusions are presented in

Section 6.

2. Literature Review

The reviewed literature provided a theoretical summary of this current study’s underpinning theories, concepts and constructs. Hence, developing a theoretical model and a hypothesis is the main aim of this research.

The emphasis in the literature has been placed on the effect of turbulent environments (TE), competent human capital (CHC) and strategic flexibility on the sustainable performance of large businesses and stable economies. Additionally, those factors’ effects were mostly explored individually and not collectively. However, the perspective of SMEs, mainly the manufacturing sector, is grossly underrepresented, particularly in developing countries with a complicated business environment such as Palestine. Therefore, enhancing the role and efficiency of SMEs is crucial since the importance of SMEs to the success of the economic growth cycle in all countries, whether categorized as industrialized, emerging or developing countries, originates from the fact that they are seen as the most important source of employment creation [

9,

40,

41]. Furthermore, governments in less developed countries depend substantially more on the performance of SMEs to generate opportunities than governments in developed countries, which rely primarily on the performance of large local and foreign enterprises [

39,

42]. Nonetheless, a country’s economic strength may deteriorate if its SMEs lack flexible strategic plans and other resources, such as fiscal resources, appropriate human resources, adequate materials and affordable energy resources [

10,

43,

44]. Accordingly, governments and other support networks must give SMEs all the help they can, including policy support and environmental laws and initiatives that are helpful for business.

SMEs are a large part of global economic growth, but material scarcity will be a big issue because they also contribute to the depletion of raw materials worldwide. By 2060, the world’s raw material consumption will have quadrupled because of growth and better living conditions [

45]. Thus, SMEs must embrace the sustainability model in their operations since different businesses always face difficulties related to sustainability’s economic, social and environmental aspects [

46]. They must improve their resource productivity, energy efficiency and manufacturing processes to be ready for the anticipated shortage of raw supplies [

47,

48]. Concurrently, manufacturers must consider fulfilling stringent environmental laws and larger cultural pressure caused by deteriorating environmental conditions [

49,

50]. Therefore, industrial firms are urged to implement new approaches to manufacturing with flexible strategies and competent human resources to encounter the turbulent environment, which could allow for attaining sustainability in the long run.

In the Arab areas, SMEs constitute an essential pillar in economic development growth by affording new openings for hundreds of thousands of youth [

10]. However, SMEs in developing economies face managerial challenges that impede their progress, underperform against expectations and endanger their continuity [

51]. These difficulties can be described as follows: there is a lack of inclusive strategic planning, a lack of competent human resources, scarce leadership skills, a scarcity of creative options to remain competitive with the turbulence in surrounding settings and a scarcity of flexible strategies to react accordingly to sudden turbulent environments [

29,

52,

53,

54]. In particular, the most senior individuals in executive positions in SMEs in developing nations lack industry and managerial skills, which lowers the progress of their firms [

51,

54,

55].

Researchers and professionals worldwide have advocated for more analysis of the surrounding turbulent environment and investment in human capital to ensure their competency and the adequate implementation of flexible strategic planning. They have also emphasized the significance of exploring the effect of those tangible and intangible managerial pillars on the sustainable performance of SMEs. Consequently, several studies have revealed that a turbulent environment (TE), competent human capital (CHC) and strategic flexibility (SF) could assist any firm, large or small, in enhancing its economic, environmental and social performance [

39,

54,

56]. Still, few studies have examined the effects of the aforementioned strategic factors on the long-term performance of manufacturing firms, especially SMEs in less developed nations. Hence, this current study examines the impact of TE, CHC and SF on SP in Palestinian manufacturing SMEs operating in a very volatile environment.

2.1. Triple Bottom Line (TBL), Contingency Theory (CT) and the Natural Resource-Based View (NRBV)

Sustainability has attracted global interest and focus due to its insightful recommendations and solutions, particularly concerning the environment and climate change [

53]. The research model developed in this current study relies on three theories: the triple bottom line (TBL), contingency theory (CT) and the natural resource-based view (NRBV) theory.

The terminologies of sustainable performance and the triple bottom line (TBL) are two interrelated concepts widely and similarly employed in the literature related to measuring and enhancing sustainability [

57,

58]. The TBL theory derives from the firm’s resource-based perspective (RBV) and links competencies to distinct processes and competitive practices that executives must combine to examine and integrate their resources, resulting in unique applications and value-added [

59]. In addition, the TBL develops a framework for assessing the performance and achievements of corporate organizations on three balanced measurements: economic, social and environmental [

60]. Economic sustainability focuses on profit maximization [

61], social sustainability seeks to develop humanity and community [

62], and environmental sustainability seeks to protect natural resources [

63]. In addition, all three will have a constructive role within the TBL, and their characteristics are essential for achieving sustainability and must be incorporated into the organizational strategy [

64,

65].

Furthermore, the TBL offers equal weight to the three bottom lines, resulting in a more balanced and coherent composition [

59,

65,

66]. The TBL approach employs more accurate value attributes and better use of existing physical and intangible resources. As a result, the company’s resources must be utilized effectively and successfully [

67,

68]. In conclusion, industrial companies are being judged increasingly on their impact on the environment and their important economic and social achievements.

Moreover, the perspective of performance in business firms and strategic planning is generated and drawn from several theories, for instance, contingency theory [

69]. In this regard, contingency is defined as anything contingent upon other factors, which implies no one-size-fits-all solution or method of leading an organization; thus, the unique solution does not function in all circumstances and business limitations [

70]. Equally, contingency theory synchronizes critical factors such as industry constraints, the external and internal environments, enterprise structure, and operations to achieve maximum efficiency at a performance level [

71]. The extant literature has highlighted that the theory was developed to challenge the classical management theory for ignoring contingent circumstances [

72]. Hence, contingency theory’s primary concept is that companies work effectively when their structures are relevant to dealing with contingencies caused by their size, technologies and environment [

73]. Contingency theory explains how business organizations align their intended results with the external and internal business environments to avoid threats and capture opportunities [

74].

On the other hand, Hart (1995) proposed the NRBV theory to incorporate environmental resources into the Resource-Based View (RBV) theory. The standard RBV emphasizes that a firm’s competitive advantage is contingent on its ability to acquire firm-level resources and competencies that are challenging for rivals to replicate [

75]. However, Hart (1995) asserts that companies’ ability to use resources to develop strategic environmental skills will determine their ability to remain competitive in the future. This advantage will go beyond the simple acquisition of internal resources and capabilities. In particular, NRBV affirms that a company’s ability to use implicit knowledge and causally ambiguous and socially complex resources to create three different types of proactive environmental strategies—pollution prevention, product stewardship and sustainable development—is essential to maintaining a competitive advantage. A review of NRBV implementation in research after fifteen years revealed that the strategic capabilities of sustainable development have arisen into two main groups, specifically clean technology and Base of the pyramid capabilities [

76]. Likewise, NRBV is a popular theoretical lens adopted by several researchers to combine green and sustainable concepts in supply-chain management. Furthermore, NRBV has been approved as a relevant theory in the context of the sustainability of the oil and gas industries [

77]. Consequently, the NRBV theory is a useful supporting basis along with TBL and CT for developing our research model.

As institutions, manufacturing firms are sensitive to the impact of the environment surrounding the business. Therefore, businesses must not only acquire and enhance their resources but improve their capacity to cope with environmental volatility. Consequently, this theory focuses on whether and what contingent circumstances influence performance.

The triple bottom line (TBL), contingency theory (CT) and the natural resource-based view (NRBV) theory could indeed help businesses enhance their overall performance. In particular, they could help SMEs to improve their understanding of how to maintain sustainable performance in their firms and develop a strategic advantage in a volatile environment by fully utilizing the capabilities and resources that are available to them. Consequently, the TBL, CT and the NRBV theory were utilized in this research study to explore the impact of TE, SF and CHC on SP in Palestinian manufacturing SMEs.

2.2. Sustainable Performance SP

The recent developments in economic and social aspects have resulted in an enormous rise in consumption worldwide, which has a major effect on the depletion of the natural resource base and may even threaten the continued well-being of human populations [

78,

79,

80]. Therefore, non-financial aspects, for example, environmental and social sub-aspects, are increasingly incorporated into overall performance evaluations in industrial firms [

81]. Similarly, monitoring merely tangible performance metrics such as financial indicators of firms has proven inadequate in the presence of dynamic competition, scarce natural and competent human resources, and increased environmental restrictions [

82]. Hence, firms must increasingly account for sustainable performance metrics to evaluate their overall performance, such as stakeholder satisfaction and environmentally friendly indicators, in addition to the traditional financial–economic measurements of productivity and profit [

83].

Sustainability has evolved into an effective concept that could be interpreted in numerous ways, contingent upon the topic and knowledge field. In the same way, “sustainability” is a broad term that includes economic, social and environmental measurements of an organization’s performance [

84]. Likewise, previous studies have shown that business firms should simultaneously maximize profit, boost company performance, promote social cohesion and protect the natural environment in order to attain the best results at all levels [

84,

85,

86,

87,

88]. Because sustainable development is receiving more attention, businesses need to carefully plan their strategies and explain how their actions help the environment and the community in which they are located [

89,

90].

Economic performance is recognized at the firm’s level as how well firms meet their short-, medium- and long-term financial targets [

91]. In addition, it refers to flexible corporate strategies and tactics that are responsive to marketplace requirements and changes by delivering goods or services without delay economically and competitively to enhance the quality of customers’ lives [

92,

93].

Environmental performance is typically the firm’s attempts to develop eco-friendly strategies and reestablish the protection of the environment, such as safeguarding ecosystems [

79,

94]. Consequently, environmental preservation strives to ensure the survival of the ecological system, including physical bodies and the brain’s life support mechanism. Additionally, in the manufacturing industry, environmental performance refers to minimizing harmful environmental effects while using natural resources, such as reducing energy use and CO

2 emission [

95,

96].

The third essential element of sustainability is social performance, which has received significantly less attention in previous studies related to sustainability [

97,

98]. Although this element is not easy to analyze compared to other dimensions of sustainability, it is still the most neglected aspect of TBL monitoring [

99]. For those reasons, the executives of firms need to be aware of how to manage social aspects efficiently in combination with economic and environmental performance [

97,

100]. In this context, social sustainability has started to alter the competitive system, driving firms to reconsider their strategies for modern products, advanced technologies, new techniques and modern business models [

101]. Consequently, the major objective of social responsibility is the maintenance of community coherence. Furthermore, social performance is related to business plans that influence the primary interests of the company’s shareholders, employees, neighboring localities and surrounding communities [

93,

102].

Previous studies in the management field have examined the different tangible and nontangible managerial elements that affect the profitability and economic performance of different sectors. However, a limited number of studies have investigated how SMEs in manufacturing industries might develop and execute flexible strategies to address sustainable performance concerns from a managerial point of view [

103]. In light of this, it is proposed that more empirical research should be carried out in order to develop a standard combination of the three key aspects of SMEs’ sustainable performance, namely the firm’s goals, its competitive advantage and its internal and external environment [

104,

105]. There are two key justifications for the emergence of studying sustainable performance in SMEs in developing countries. Firstly, SMEs are regarded as vital and vibrant components of all countries’ economies. Consequently, SMEs must cope with internal obstacles and external limitations that impact economic, social, and ecological performance [

80,

106,

107]. The other crucial role of SMEs is assisting countries to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

92,

107,

108].

Examining how elements such as TE, CHC and SF influence SP in a developing country such as Palestine, with a volatile business and political environment and low firm performance, is essential. Consequently, this study defines SP as a firm’s aptitude to include social, environmental and economic considerations in its performance metric [

109]. As a result, social, environmental and economic performance are viewed simultaneously, not separately, which could support SMEs in identifying hands-on recommendations and conceptual approaches that help them expand, prosper and remain in business [

84,

85,

86,

87,

88].

2.3. Turbulent Environment (TE)

Prior research has not sufficiently explored the effects of a turbulent environment. In this regard, a more political understanding of business differences—notably the ability to manage positive political relationships—can explain the considerable share of variance normally assigned to company impacts [

110]. Frequently, firms face external influences beyond their control, which are complicated to manage and which may not be completely removed from the company itself [

16]. Moreover, rapidly changing business environments are frequently defined by the attributes of their surrounding environment, including market instability, technological innovation, competitiveness and the overall economic climate [

17,

110]. Several scholars have generally agreed that an uncertain business environment influences the performance of business firms, affecting sustainability both domestically and overseas [

18].

In addition, firms operating in dynamic conditions and unpredictable contexts must embrace a much less centralized and more flexible structure [

19,

37]. Despite the complexity of formulating a strategy to encounter an uncertain event, it is essential to reassess the procedures under which techniques are developed and the essence of the strategic plan [

111]. Grant (2003) examined strategic planning under a TE and found that firms should consider several points to reunite flexible strategies with unstable business surroundings, such as focusing more on multiple scenario planning, which visualizes alternative opinions of the long-term in the arrangement of unlikely setups of vital environmental parameters, thus highlighting the importance of adapting SF in order to generate option values; second, due to the uncertainty, the strategy should be less concerned with various activities and more focused on developing clarity of direction within which the short-term and overall coordination of strategic decisions must be reconciled [

112].

For most businesses working in a highly chaotic environment, there is a high risk of ambiguity, necessitating a high level of effective, flexible strategic management. Hence, for industries to prosper and maintain a competitive edge, businesses would need to find the appropriate resources and capabilities to ensure that they can deal with an external environment that has become much more sophisticated. Consequently, flexible strategies, innovation and talented human resources would become particularly crucial as the external environment becomes more complex. In the context of Palestine, those above-mentioned components of the TE all exist, adding to the political instability in the country.

2.4. Competent Human Capital (CHC)

Businesses should place particular emphasis on the ability of their human capital, which will be responsible for executing strategies and achieving goals. Similarly, the capability and flexibility of SMEs’ human resources are crucial for attaining desired business results [

38,

113]. Ajike et al. (2016) recommended that for SMEs to flourish, grow and attain sustainability, managers of SMEs must be flexible and stress enhancing “human capital” and “spiritual capital” in a collaborative way [

114]. Muñoz-Pascual et al. (2021), in their research on SMEs in Spain titled “Contributions to Sustainability in SMEs”, recommended SMEs to be resilient in enhancing the skills of the core elements of human resources, namely “knowledge, motivation, and relationships”, which can influence the creativity of SMEs positively [

12]. SMEs should be resilient and carefully consider their human capital investments, which include opportunities for formal and informal education, on-the-job training, the establishment of adequate health care and safety systems and the retention of highly qualified employees who are highly involved in strategies, as well as the retention of satisfied and committed employees, all of which are considered essential pillars in the process of accumulating knowledge, enhancing skills and increasing commitment [

14,

115,

116]. It is worth mentioning that employing green intellectual capital practices, such as the employment and selection process, green prizes and green structural, could positively influence companies’ sustainability [

81,

115]. Therefore, the personnel of a firm is the primary intangible asset responsible for generating value, improving quality and maintaining sustainability.

Most prior related studies in this field have highlighted that CHC substantially improves the performance and sustainability of industrial enterprises. Xu et al. (2019) found a positive impact of implementing adequate human capital on the SP of the listed manufacturing SMEs in China [

117]. Likewise, Lubis and Muchtar (2019) recommended that Indonesian SMEs adapt and develop a comprehensive strategy that comprises intellectual capital as the central pillar of strategy to overcome the swift fluctuations and dynamics in markets, thereby enabling them to generate nonstop “competitive advantages” that lead to sustainability [

118]. Other limited relevant research found a negative association between CHC and attaining competitive benefits in firms [

119]. Some studies have found insufficient evidence to establish the links between CHC and performance [

120].

Despite earlier studies that have found a positive influence of CHC on firms’ success, the association between CHC and SP remains uncertain. Consequently, researchers believe that significant inconsistencies exist in the literature, something that needs to be further explored in developing countries, such as Palestine. Scholars and researchers have suggested further studying the consequence of intellectual capital in developing countries in different SME sectors to bridge the gaps in the literature.

2.5. Strategic Flexibility (SF)

Firms must be prepared to handle the unpredictable changing aspects of markets, regulations, technological advancement, digitalization and pandemics (such as the COVID-19 pandemic) [

9,

121]. Therefore, SF has become a crucial enabler that can assist decision-makers in realizing the desired SP [

122,

123]. Although there is no agreement on a scientific definition for SF, there are different definitions in the literature. However, SF can be broadly defined as efficiently treating and dealing with an urgent change [

124].

SF is the capacity or ability of companies to be alert and proactive in responding to uncertainties and rapidly adjusting to changing competitive surroundings, contributing to flourishing and sustaining competitive advantage [

125]. Furthermore, SF is a critical administrative necessity to support business players in successfully managing unexpected dynamic environments [

72,

126]. Hence, SF enables decision-makers to achieve higher performance through the availability of strategic options that allow them to handle or manage the change. Therefore, firms equipping themselves with resilient strategies can speedily encounter emergencies and adjust to unstable surroundings; they might face a TE much better than firms without flexible strategies, enabling them to attain a better competitive advantage [

39]. Conversely, failure to attain the desired sustainability can be attributed to the failure of firms to deploy SF [

127].

Earlier studies have shown no consistent conclusions on the effect of SF on the performance of firms [

122,

127,

128]. Prior studies may have been subject to various limitations that influenced their results. In addition, several researchers have revealed that the size and structure of firms could define the impact of SF on performance [

39,

129]. Nevertheless, the findings on the effects of SF by researchers are still inconclusive and need further exploration [

56].

Studying and investigating the impact of SF on business performance, developing sustainable strategies for SMEs and developing policies to support SMEs can provide SMEs with an opportunity to evaluate improvements regularly, as well as a stage from which to capture available options and avoid associated threats. It also gives firms a logical guide to evaluate, correct and modify the actions required to strengthen the association between SF and business performance [

39,

124,

130]. On the one hand, related prior studies on this critical subject in SMEs are limited and non-inclusive compared to big and large corporations; on the other hand, SMEs face severe challenges in the competitive business environment when compared to larger-sized firms [

39,

131,

132]. Brozovic (2016) highlighted that studies on the flexibility of strategies are very limited; therefore, tools approaches to measure the impact of SF on the performance of SMEs are absent, hence the need for further exploration in future studies [

124].

SMEs’ decision-making process is widely considered an old style, meaning that creativity in employing spot decisions or “improvisational decision” is uncommon in SMEs [

127]. Hence, flexibility is much needed in daily and strategic decisions. In other words, SMEs must be proactive and take immediate actions to respond and react effectively to the changeable business environment [

133]. Lastly, SME executives must be encouraged to include flexibility in their strategies to enhance production efficiency. Therefore, industry experts in SMEs must pay closer attention to developing sustainable plans while concurrently emphasizing a flexible approach because a resilient and sustainable strategy can ensure that SMEs stay competitive in a constantly and rapidly dynamic business environment.

2.6. Hypotheses Development

The research model and hypotheses for this study were established and validated based on a comprehensive literature analysis to examine the potential of three variables: turbulent environment (TE), competent human capital (CHC) and strategic flexibility (SF). Consequently, this study explores the association between these variables and the sustainable performance (SP) of Palestine’s SME manufacturing industry.

Regarding CHC, there are several reasons CHC was chosen as the second independent variable: first, CHC is considered a significant catalyst for growth, comprising employees’ knowledge, cumulative expertise, continuous education and aptitude [

134]. Second, CHC is acknowledged as a critical component of a business’s success in a competitive climate [

38]: the Middle East and North Africa region (MENA), of which Palestine is a part, faces a severe human capital deficit, and regional governments should recognize the seriousness of the issue and identify and set priority actions that may assist in creating, protecting and utilizing human capital by supporting and enabling youth and the elderly [

135]; moreover, the Arab Monetary Fund (AMF), in a study conducted in 2020 to “compare the effects of human capital on economic growth in the Arab countries compared to some Asian and OECD countries”, has found that considerable work is required to catch up with industrialized countries since the Arab countries’ contribution to human capital is nearly half that of advanced countries [

136]. Therefore, it recommends exploring and enhancing the role of CHC in Arab countries. Accordingly, the study’s hypotheses linked to CHC are given below.

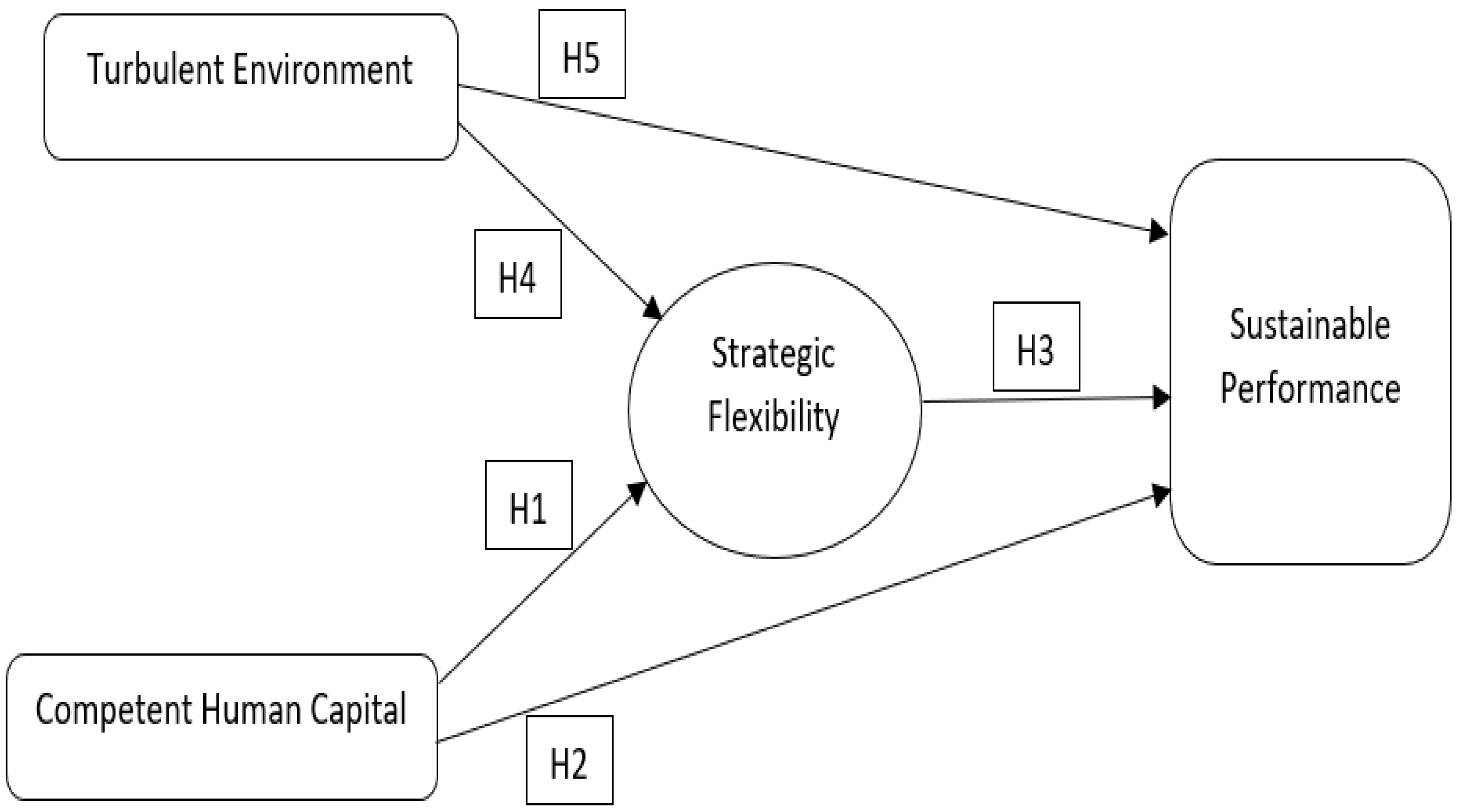

H1: Competent human capital is positively related to strategic flexibility in manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises in Palestine.

H2: Competent human capital is positively related to sustainable performance in manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises in Palestine.

As for strategic flexibility, there are also several reasons why it was chosen as an important variable to be studied; according to Brozovic (2016) [

124], an examination of the literature on the consequences of SF reveals that the majority of the prior studies concentrated on the strong association between SF and greater performance and competitive benefit in huge firms, whereas other topics, such as SF in SMEs and the undesirable effects of SF, generally remain unexplored. In addition, Tan and Wang (2010) found contradicting outcomes from multiple measurements of whether resource flexibility increases performance in turbulent settings depending on the extent to which they have been fascinated with manufacturing operations and suggested more future studies to find different impacts [

137]. Furthermore, Ebben and Johnson (2005) found that firms that varied productivity and flexibility strategies performed less severely. Lastly, efficiency and flexibility methods are easy to categorize for smaller companies that manufacture items, but they may be more difficult to categorize for retail or other sorts of businesses and require further study [

138].

The success of a business, viewed from the perspective of the contingency approach as an open platform, is contingent upon both internal and external circumstances. Moreover, while recognizing the value of the outside industrial environment in manufacturing SMEs, the boundary limits of SF in reviving business performance have not been studied comprehensively. In this study, an attempt has been made to systematically manage a firm’s turbulent environment.

Considering the earlier explanation, we suggest the hypothesis below:

H3: Strategic flexibility is positively related to sustainable performance in manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises in Palestine.

The turbulent environment was chosen as one of the independent variables for various reasons. According to [

37], SMEs usually encounter a turbulent environment; in these circumstances, traditional performance approaches, such as performance appraisal, would not function effectively. Therefore, time is precious in uncertain environments; firms that insist that they have perfected making quick judgments without complete data will not succeed. Furthermore, Western and developing countries have been the focus of most research into the effects of turbulence on corporate performance, with only a small number of studies focusing on less developed countries such as Palestine [

139]. Similarly, Palestinian SMEs in the manufacturing industries are among the main importers of raw materials; they witness unstable import processes due to political conflict [

28]. Accordingly, this contextual gap necessitates more examination. Finally, conventional techniques for strategic planning are vital but insufficient in guaranteeing firm sustainability. Therefore, the nature of encountered changes influences the strategic options, so managers should develop appropriate plans to enable their firms to deal with uncertainty [

140].

For all these considerations, an additional empirical study is required in Palestine to confirm earlier findings about the relationship between a turbulent environment and sustainable performance. In addition, the Palestinian SMEs’ unique environment, business practices and cultural composition may provide additional insights into this relationship. As a result, the following are the turbulent environment-related study hypotheses:

H4: Turbulent environment is positively related to strategic flexibility in Palestinian manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises.

H5: Turbulent environment is positively related to sustainable performance in Palestinian manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises.

Figure 1 depicts the theoretical framework constructed for this research.

3. Methodology

The data for this study were gathered from Palestinian SMEs in manufacturing sectors through a well-structured survey from the beginning of April to the end of July 2022. Moreover, the sample list was obtained from the Palestinian Federation of Industries (PFI), the umbrella of Palestinian manufacturing firms. In order to complete this study, a straightforward random sample procedure was chosen because probability sampling is a great method for obtaining statistical data from multiple sources and gaining an overview of what the entire population is like since it includes looking at a random sample [

141]. The senior executive level in SMEs, including owners, board members, general managers, financial managers, plant managers, etc., is the analysis unit in this study because of their direct involvement in the strategy development, human resource management, strategic entrepreneurship, manufacturing methods, knowledge and competence of their industries [

142]. Hence, they could respond quickly to the study’s survey.

The dependent variable of this study is sustainable performance (SP), which is impacted by three independent factors in the recent research design: turbulent environment (TE), competent human capital (CHC) and strategic flexibility (SF). Consequently, the minimum required sample size was first calculated using the well-known computer program G*power, and a sample size of 166 was determined to be adequate for this study [

143]. Nevertheless, ref. [

144] suggests a higher sample size is necessary to represent the entire population accurately. Accordingly, 380 surveys were distributed to the SMEs’ top management directors, and 245 were deemed acceptable after being gathered, yielding an adequate 64.5% response rate.

In order to precisely quantify the constructs in the theoretical model, multi-item measures were utilized. The study constructs were evaluated using a scale of the type known as the Likert scale, which consists of five points ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The survey questions were made so that each respondent’s level of agreement with each statement could be used to measure how they felt about the variables [

145,

146]. Furthermore, participants answering the questionnaire from SMEs were requested to assess each item on a scale from 1 to 5. In the same context, three academic experts assessed the survey to increase its validity by ensuring clarity and avoiding ambiguity.

The researchers relied on the related literature in the operationalization of the study constructs as indicated in

Appendix A. In this regard, the operational subitems of the turbulent environment TE were adapted from [

19,

147] and measured by five sub-items. Similarly, competent human capital (CHC), the second independent variable, was operationalized by measurement of five sub-aspects of CHC and adapted from the relevant study [

148]. The third independent construct, strategic flexibility (SF), was measured by six subitems and adapted from [

39].

The conventional operational assessment of a company’s performance involves evaluating economic metrics, including total income, profit margin, sales growth, etc. However, operational measurements of the dependent variable (sustainable performance) must include the social, environmental and economic aspects of an organization’s performance at the same time [

149]. The following method of measuring sustainable performance in this study, which entails five items, is adapted from [

39,

97].

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was utilized, alongside the Smart PLS 4.0 package set, to analyze the acquired data. This kind of analysis was used because the nature of the study was exploratory [

150,

151].

The PLS-SEM approach allows researchers to estimate complex models with multiple constructs, indicator variables and structural paths without putting distributional assumptions on the data. It is a causal–predictive approach to SEM that stresses prediction in estimating statistical models, the structures of which are meant to give causal explanations. As a result, the method overcomes the seeming tension between explanation—as traditionally stressed in academic research—and prediction, which serves as the foundation for creating management implications [

152]. A two-stage process was used to assess the data that had been gathered. The validity and reliability of the constructs were observed and evaluated in the first stage, known as the measurement model. The hypotheses were evaluated in step two [

153,

154].

5. Discussion

In terms of the main purpose of this study, TE, CHC and SF are viewed as crucial managerial drivers for enhancing the SP in SMEs, specifically manufacturing ones in Palestine. In this regard, it was observed that there is a strong positive relationship between CHC and SF. The B-value of the CHC–SF association was 0.296, significantly more than 0.1. Furthermore, the T and

p-values in

Table 5 reveal a significant association between CHC and SF, as the

p-value was less than 0.05 and the T-value was larger than 1.96. Hence, this indicates that hypothesis H1 is significant: Competent human capital is positively related to strategic flexibility in manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises in Palestine. This result aligns with the results of other earlier studies [

56,

166,

167].

Similarly, a positive relationship was found to exist between CHC and SP. The B-value of the relationship between the CHC and the SP (the dependent variable) was 0.252, significantly more than 0.1. In addition,

Table 5 shows that the association between CHC and SP was also significant, as the

p-value was less than 0.05 and the T-value was larger than 1.96. Thus, this empirical research confirmed that CHC favorably influences SP in Palestinian SMEs in the manufacturing sector, supporting hypothesis H2: competent human capital is positively related to sustainable performance in manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises in Palestine. This finding is consistent with the results of other earlier research, which showed a positive and remarkable impact of CHC on business sustainability and success [

38,

81,

113].

Referring to the connection between SF and SP, a positive and solid relationship existed between the two. Furthermore, this was the strongest association among the variables. The B-value between the variables SP and SF was 0.475, which is significantly more than 0.1, meaning that the more the SMEs are resilient and flexible to adapt different strategies to encounter different changes, the more SP can be achieved. According to

Table 5, the T and

p-values also indicated that the association between SF and SP was significant, as the

p-value was less than 0.05 and the T-value was larger than 1.96. This result is consistent with the results of earlier studies, which showed a positive influence of SF on the performance of different business firms [

39,

123]. Thus, this supports hypothesis H3: Strategic flexibility is positively related to sustainable performance in manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises in Palestine.

A positive relationship was found to exist between TE and SF. The B-value of the SF–SP linkage was 0.412, which is significantly more than 0.1. Furthermore, according to

Table 5, the T and

p-values revealed that the association between SF and SP was significant, as the

p-values were less than 0.05 and the T-value was larger than 1.96. This indicates the validity of hypothesis H4: turbulent environment is positively related to strategic flexibility in Palestinian manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises. This finding is consistent with the findings of earlier studies, which showed a positive impact of TE on firms’ SF [

168,

169].

In the same context, the B-value of the linkage between TE and SP was 0.173, which is also higher than 0.1. Hence, the real impact of TE on SP in Palestinian SMEs in the manufacturing sector was a significant and positive relationship. Furthermore, the T and

p-values proposed that the correlations between TE and SP were significant since the

p-value was less than 0.05 and the T-value was greater than 1.96. As a result, hypothesis H5 is supported and significant: turbulent environment is positively related to sustainable performance in Palestinian manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises. This finding confirms what numerous prior studies have suggested and shown that TE significantly impacts performance in business firms [

18,

139,

170].

The results of this current research support the TBL and contingency theories. In this regard, CEOs and senior managers in SMEs could invest in competent human capital, employ strategic flexibility, and properly assess the surrounding turbulent environment to achieve a competitive benefit in the market, eventually preserving their company’s success to attain sustainable performance at all levels, including balanced economic, environmental and social performances. The results show that competent human capital, strategic flexibility and an analysis of the tumultuous environment are important management factors that affect how well firms run and can encourage other SMEs to take innovative and proactive steps to enhance their endurance.

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

There is a lack of previous relevant studies that focus on the correlation between CHC, SF, TE and SP in SMEs in Arab countries, mainly the manufacturing sector in the Palestinian context [

29,

171,

172]. This study adds to the body of knowledge about SP in manufacturing SMEs in underdeveloped countries suffering political and economic turbulence, such as Palestine. Consequently, the findings of the study show that (CHC), (SF) and (TE) are critical management techniques for manufacturing SMEs working in a highly dynamic and competitive context.

The triple bottom line (TBL) theory, natural resource based view (NRBV) and contingency theory (CT) were applied through the lens of the variables in this current study to investigate the research problem. The implications of the theories and their importance are included in the scope of the study. Therefore, this paper aims to fill this theoretical gap in the previously published studies. In this context, this article’s literature review section extensively explains that various theoretical frameworks can be used to address the current research problem.

This study investigates the relationship between (CHC), (SF), (TE) and (SP) in the manufacturing sector in Palestine, mainly SMEs, which is hindered by an unpredictable and turbulent environment that impedes its success and expansion. Various studies examine the influence of CHC, SF and TE on company performance individually, rather than collectively, in large corporations, professional organizations and huge industries operating in politically stable environments. Few studies had been conducted in less developed economies with unstable business environments [

54,

112,

172,

173].

Moreover, prior studies that examined the relationship between (CHC), (SF) and (TE) and the performance of the companies individually tended to focus on companies in developed nations such as Western countries. Consequently, this study adds to the existing body of knowledge since it presents a theoretical framework for examining the interrelationship between these three independent variables and the dependent variable of (SP). In comparison, this is one of the first studies to analyze and examine the relationships between (CHC), (SF), (TE) and (SP) in the setting of under-developed economies, notably in an area experiencing a particularly turbulent situation.

In contrast to the majority of past studies, this study focuses on extending the interpretation of performance measurement in business firms, mainly SMEs, which has previously been limited to measuring only profitability ratios, to include non-financial metrics by considering social and ecological indicators in addition to the economic ones outlined as SP in this study. [

50,

174].

5.2. Managerial and Practical Implications

Given the unrest in the political environment, Palestine is perceived as an unstable country in which direct investment from abroad is constrained and does not emphasize manufacturing industries [

24,

175]. Furthermore, because most Palestinian firms are categorized as SMEs with very limited resources, there is very little knowledge about the influence of managerial drivers such as competent human capital, strategic flexibility and turbulent environments on sustainable performance in business firms. Likewise, SMEs in Palestine typically pay less attention to business strategy, focusing on instantaneous business results while ignoring strategic business consequences [

26,

176].

Accordingly, Palestinian SMEs, mainly manufacturing ones, face both external and internal difficulties that impede their success and long-term viability. The mentioned issues are because their strategic plans are not flexible enough, their human capital and leadership are not strong enough, and they have not become well-institutionalized firms. In this regard, several industry players in Palestinian SMEs have been unable to adopt the right quality procedures, national and international standards and different ISO standards. Therefore, ensuring the proper management of CHC, SF and TE can help solve most of these problems and enhance their sustainability [

25,

28,

175].

In a world of escalating unpredictability, SMEs must be flexible to attain sustainable performance. One of the main results of this study provides important insights and a vital recommendation for the proper management of competent human capital, strategic flexibility, turbulent environment and sustainable performance. The article suggests that executives of SMEs should prioritize strategic flexibility and sustainability performance to stay competitive in a fast-changing business setting. Senior executives, for example, should be strongly encouraged to think creatively about improving their company’s performance through strategically flexible management; this is especially suggested, necessary and stressed for executives of SMEs in developing countries such as Palestine, where turbulence and rapid change in the business environment is common. Furthermore, SMEs should improve the efficiency of their materials, resources and energy use by implementing strategic flexibility, which can be used to boost productivity.

Furthermore, this research showed that sustainable performance strategies must be adopted by SMEs so that strategic flexibility excels and promotes firm performance. Therefore, SMEs must properly arrange their assets, generate new innovative products, participate in increasing employment, and join international markets. Hence, strategic flexibility helps Palestine’s SMEs plug and capture environmentally-driven business opportunities.

Additionally, the findings have managerial implications by highlighting the value of competent human capital as a resource for maintaining high levels of sustainable performance in manufacturing SMEs. Moreover, the findings demonstrate that investments in human resources improve business performance in different ways, such as through increased productivity, decreased expenses and better outcomes at the social and environmental levels. Ultimately, this research highlights the value of human resources as a strategic asset. Therefore, managers of SMEs must be aware of how to improve the quality of human resources and, more crucially, how to employ human resources to boost creativity and productivity. Executives can maximize the value of their company’s human resources by, for example, offering rewards, providing managerial and technical training, providing opportunities for professionals to grow, and setting goals and measures directly tied to employees’ performance.

These study findings can be utilized as a guide to advise business owners and directors in determining which practices are best suited to increasing the effectiveness and sustainable performance of a business in a developing economy facing a turbulent environment. Consequently, it is anticipated that the present study’s new empirical findings function as an opportunity for the leadership of SMEs to remain aware and concentrate more on directing the best resources to increase business performance. Moreover, the senior management of SMEs can utilize the various aspects and measurements developed in this study as a diagnostics tool for assessing the sustainable performance of their SMEs. The study’s findings can serve as a motivator to practitioners to the significance of competent human capital, strategic flexibility and the effect of analyzing the turbulent environment in increasing the sustainable performance of SMEs.

At the policy level, the study recommends that governments provide manufacturing SMEs with focused awareness and training to boost sustainable performance, along with emphasizing the drivers to attain it, such as encouraging business innovation, investing in competent human capital and implementing proper and flexible strategic planning. In addition, the study offers policy implications for fostering continuous analysis of the impact of the turbulent environment on Palestinian SMEs. In addition, the government needs to revisit and resolve the structural problems facing SMEs at the policy level to provide an enabling and attractive environment for doing business and improving manufacturing SMEs’ growth.

5.3. Future Research

The scope of this study focuses mainly on the Palestinian SMEs involved in manufacturing operations. Future research can use a qualitative technique to address study questions through interviews with owners and executives. Furthermore, this study could be developed and applied to other organizations in Palestine’s private and governmental sectors. For instance, it could be conducted in large industrial and service-oriented firms such as banks, hospitals and telecommunications. It could yield interesting findings by examining a model that combines these variables in other sectors. Future research could also be conducted to acquire a more comprehensive conclusion by including different types of internal or external strategic variables, such as market orientation and access to finance, digitalization, knowledge management and others, to help understand the issue of sustainable performance. Furthermore, the authors suggest future research exploring the relationship between the variables of turbulent environment and competent human capital, for example, an investigation of the mediating role of competent human capital on the relationship between turbulent environment and sustainable performance.

6. Conclusions

SMEs are crucial to economic growth in developed, emerging and developing countries. The high percentage of unemployment rate, the high cost of imported materials, the high rate of SME bankruptcy and economic instability are only some of the problems that Palestine, a developing country living under turbulent business surroundings, must encounter effectively. In light of these and other challenges, SMEs are often seen as a solution and a great way to minimize these challenges. However, SMEs in Palestine continue to underperform because of a lack of CHC and SF and a weak understanding of TE. This research explored the connections between CHC, SF, TE and the SP of the SMEs in Palestine in the manufacturing industries to help identify steps towards achieving SP.

This study is extremely useful in guiding senior management and executives in SMEs toward more comprehensive and appropriate management practices, such as implementing more flexible strategies, increasing investment in human resources, involving human capital in the strategy development process and gaining a better understanding of how the external turbulent environment affects sustainable company performance. The research results show that SMEs in Palestine need a high level of competent human capital to remain competitive in the volatile marketplace. By showing how well CHC positively influences SP, the study also highlights how important it is to improve human resources to help SMEs grow sustainably as part of the country’s economic development.

Moreover, the findings imply that SMEs in Palestine, specifically the manufacturing industries, must improve their strategic flexibility to achieve higher sustainability performance. In practical terms, it is obvious that companies that wish to endure and thrive in years to come must be equipped with executives and talented human resources who are capable of overcoming their technological and cultural obstacles and employing strategic flexibility properly. Hence, firms confronting accelerated environmental turbulence should prioritize their proactive and responsive strategy flexibility. In this regard, several business firms globally and locally have incurred high costs for resistance to change, as recent events have proven. Hence, the assumption that companies must evolve when encountering new challenges is central to strategic management and contingency theory.

Lastly, businesses must have extensive flexible strategic planning to adapt to uncertain and volatile situations. Thus, companies typically could react to uncertainty by making tactical changes to products, services and processes.